Chapter 9

Landscape planning

Many years ago, delegates at a European conference of landscape architecture academics were presented with a task. They were each given a list of terms—‘landscape architecture’, ‘landscape design’, ‘landscape planning’, ‘garden design’, ‘garden art’, and so on—each represented by an arbitrary geometrical shape, and they were each asked to produce a drawing which showed the correct conceptual relationship between these fields. So, if garden design was represented by a square and landscape architecture by a circle and a delegate thought that garden design was completely encompassed by landscape architecture, he should draw a circle enclosing a square. If two fields might be said to overlap, they could be represented by two shapes that crossed. To no one’s great surprise, every diagram that emerged was different.

It might be interesting to repeat this experiment, after more than two decades of international discussion and progress towards integration, but I expect that even now there would not be total agreement. I hope there would be general recognition that the overall title of the discipline is ‘landscape architecture’, despite the shortcomings of that name. I also think there would be recognition that under this umbrella term there are two complementary activities called ‘landscape design’ and ‘landscape planning’. These undoubtedly overlap, but I am going to try to distinguish between them. The conventional way to do this is to draw up a list of binary oppositions, as follows: design vs. planning; artistic vs. scientific; small sites vs. extensive regions; creative vs. problem-solving; synthetic vs. analytic; serves individuals vs. serves society. This list gives some sense of the difference between two sorts of activity. It is also undoubtedly true that some landscape students are instinctively drawn toward the more artistic aspects of landscape architecture, while others are happiest when analysing survey material, preparing plans, or writing reports. However the inadequacy of this binary split was demonstrated by Professor Richard Stiles from the Technical University of Vienna, who observed that landscape cannot easily be split into small sites and large territories. It is a continuum, with intimate, garden-like spaces at one end, neighbourhoods and networks in the middle, and regional landscapes and whole watersheds at the other end. Similarly, it is impossible to say that creative design involves no analytical thinking or problem-solving. It generally does. Stiles was pointing out that planning and design were not really separate activities with distinct theoretical bases. The relationship between design and planning is more like the yin and yang symbol: there is always a bit of planning in design and a bit of design within planning (this is my observation, not Stiles’). There are, however, paradigm cases. When a landscape architect prepares a design for a site which is entirely within the control of a private client, such as a garden, the activity would usually be called design, though it includes aspects of planning, such as working out where the best place for the vegetable plot might be. A landscape architect often has to employ much the same skills when designing a park or a public square, though the client is no longer a private individual. Managing large estates on behalf of large landowners, whether individual or corporate, is often a rationally based activity, but aesthetics may nevertheless come into consideration—it would be usual, though, to think of this as planning. Finally, we have the classic landscape planning scenario, where the landscape architect must prepare a plan on behalf of a local administration for the land over which it has jurisdiction. Again, this might seem to be a largely rational decision-making process, but it often has to take aesthetic, cultural, and even spiritual values into account.

Origins of landscape planning

Landscape planning’s origins lie in the anti-urban attitudes fostered by Romanticism and Transcendentalism, and from an urge to protect nature against perceived human encroachment. As we saw in Chapter 5, Frederick Law Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture, worked with naturalists to secure the protection of what they thought of as pristine landscapes in the American West. The philosophy underlying this is aptly summed up in Thoreau’s aphorism ‘in Wildness is the preservation of the World’. For Thoreau and for Olmsted ‘wilderness’ and ‘the West’ were synonymous, so preservation meant the exclusion of human activity. As the environmental historian William Cronon has pointed out, this conception of wilderness was flawed from the outset, because it ignored the fact that these so-called wildernesses had for centuries been the cultural landscapes of Native Americans. Nevertheless it gave us the notion of the designated and protected landscape and, specifically, of the national park. In America this meant a place where no people lived at all, but when Britain designated its first national parks, shortly after the Second World War, these were cultural landscapes such as the Peak District and the Lake District, where the character and aesthetics of the landscape depended on centuries-old farming practices. The idea of ‘natural beauty’ is enshrined in much British planning legislation, although it is a very slippery concept to define. Countryside is, after all, a hybrid of natural and human processes. Britain has a swarm of landscape designations, some related to history, some to scarcity of habitat, some to cultural significance and scenery, and all bearing upon the drafting of development plans, thus helping to determine what may be built where.

There are international designations too, such as the Ramsar Convention which lists globally significant wetlands, recognizing their scientific, ecological, and cultural value; but soaring above all of these, at least in status, is UNESCO’s listing of World Heritage Sites. To get into this elite category a site must have ‘outstanding universal value’. It was established with the idea of protecting our collective global patrimony, safeguarding cultural gems like the Acropolis or natural wonders such as the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef, but the rules were later changed so that cultural landscapes, hybrids of culture and nature, could also be included. Some designed landscapes, such as the classical Chinese gardens of Suzhou are included as cultural artefacts, but so is the Göreme valley in Cappadocia, Turkey, where vernacular homes were carved out of the soft rock amid a spectacular landscape of natural pinnacles and towers.

As we have already seen in earlier chapters, this desire to protect the perceived beauties of nature was balanced by a mission to improve living conditions in overcrowded cities. The benefits of open space within cities had long been recognized and promoted. William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia prefigured the Garden City Movement with his vision of a ‘greene Country Towne’. He had survived London’s bubonic plague in 1665 and the great fire of 1666, so he wanted buildings to be set in large plots surrounded by open space so that the new city ‘will never be burnt and will always be wholesome’. Notice that Penn’s plan promoted both safety and public health; the idea that open spaces can provide benefits of many different kinds is still at the heart of contemporary thinking—in contemporary jargon it is ‘multifunctional’ and ‘cuts across multiple policy agendas’. Planning-speak may be opaque, but at least it is colourful: this totality of parks and gardens can be considered ‘greenspace’, never to be confused with ‘brownfields’, but there is also ‘bluespace’, the collective term for rivers, lakes, ponds, and other water-bodies within the urban fabric. Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace, a linked chain of parks in Boston and Brookline, MA, would nowadays be described as a ‘greenspace network’ which is not quite so poetic, but essentially the same idea. Patrick Abercrombie’s Greater London Plan of 1944 was based on a systematic survey of the existing landscape and recommended the establishment of a Green Belt to contain sprawling urban development and a system of open spaces based around parks, green spaces, and river corridors.

McHargian landscape planning—landscape suitability

Ian McHarg, too, was concerned about unrestricted development. The idea that some developments are more suitable to some landscapes than to others seems only commonsense, but when homes built on floodplains are inundated or hotels built on cliff tops fall into the sea, the extent of human folly becomes evident. We could avoid such calamities and live more harmoniously with nature, thought McHarg, if we took natural processes and values into account. He proposed a method for bringing everything into the picture. Known as ‘landscape suitability analysis’ or sometimes just as ‘sieve-mapping’, the technique he developed involved layering information on acetate sheets. So, for example, in considering the optimal route for a new highway, McHarg would combine layers showing the engineering properties of the substrates with layers showing productive soils, significant wildlife habitats, important cultural sites, and so on. When these were combined, it was the areas which were clearest of symbols that were the better areas in which to construct the road. The method also worked well for planning development at a regional scale. Typically, after gathering physiographic, climatic, and geological data, McHarg could produce suitability maps, usually zoned for agriculture, forestry, recreation, and urban development. The method, which relied on extensive gathering and manipulation of data, became much easier with the growing availability of computers, and ‘McHarg’s Method’ became the basis of the technology known as GIS (Geographical Information System) which uses digital map layers instead of superimposed drawings. The advent of landscape ecology also enriched McHargian landscape planning. It provided the theory to explain why some ecosystems might decline and also suggested principles whereby they might be safeguarded and improved.

In general landscape planning does not begin with a blank slate. The polder landscapes created in the Netherlands in the 20th century are the exception that proves the rule. Here, where new land was won from the sea, it was possible to start from scratch, planning farms, dikes, road, settlements, and woodlands. These flat landscapes, with their straight lines and rectilinear shapes are the epitome of rational planning, but they have their own striking aesthetic. Most places, however, do not come off a drawing board in quite the same way. Most landscapes have developed over centuries and they are layered. The term ‘palimpsest’ (the name for a Roman tablet or mediaeval scroll, partially erased to be re-inscribed) is often used to express the idea that even if a landscape is altered, traces of its history will still remain. Most landscape planning begins with something rather complicated, and we cannot even say that this is a complex object because, as many theorists have pointed out, landscape is something mental as well as physical, something subjective as well as objective.

From special landscapes to the whole landscape

Though the origins of landscape planning were in the designation and protection of areas of countryside considered to be exceptional, the adoption of the European Landscape Convention in 2000 (a Council of Europe treaty) signalled a significant shift in thinking. The Convention’s definition of landscape as ‘an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors’ recognized that landscape was not just physical. It was something ‘perceived by people’, in other words, something both understood and shared. Landscape was recognized as ‘an essential component of people’s surroundings, an expression of the diversity of their shared cultural and natural heritage, and a foundation of their identity’. In the Article headed ‘Scope’ the Convention states that it ‘applies to the entire territory of the Parties and covers natural, rural, urban and peri-urban areas. It includes land, inland water and marine areas. It concerns landscapes that might be considered outstanding as well as everyday or degraded landscapes.’ This does not mean that the old protective designations around such places as the Plitvice Lakes National Park in Croatia or the Pyrenees National Park in France are about to disappear, but it does mean than politicians and planners have to also consider policies for recognizing and conserving the qualities of everyday landscapes, closer to where most people live, and improving landscapes which are considered to be failing in social, economic, ecological, or aesthetic terms.

The European Landscape Convention also marks a big shift away from decision-making by experts towards decision-making by ordinary people. What it actually calls upon signatory states to do is to ‘establish procedures for the participation of the general public’ alongside local and regional authorities in the definition and implementation of landscape policies. It is all open to interpretation, of course, and doubtless the practice in various countries will differ, but it is a shift nonetheless. Landscape planners will no longer be able to rely upon their own judgements, no matter how well informed they may consider themselves to be. Experts will still be needed, but expertise in facilitating participation will be at a premium. A campaign is currently pressing for an International Landscape Convention, backed by the United Nations, so these considerations may soon apply to the whole world.

Assessing the quality of any landscape is a question fraught with difficulties. Attempts to do this quantitatively, by scoring the features found in map squares, for example, were eventually abandoned and replaced, at least in England and Scotland, by a method known as ‘landscape character assessment’ (LCA), developed in the 1980s by the office Land Use Consultants, which endeavours to separate the description of landscapes from any judgements that might be made about them. A complementary method, known as ‘historic landscape characterization’ (HLC) adds ‘time-depth’ to the description. In line with the European Landscape Convention’s shift away from red-line designation of special landscapes, HLC is particularly concerned with how to protect and manage dynamically changing rural landscapes. If we admire landscapes because they are palimpsests of past change, logically we must be prepared to allow further change. The question is what scale and speed of change is acceptable, and here, once again, it is important to engage with public opinion.

Environmental impact assessment and visual impact assessment

Much of the planning work which landscape architects do is tied to particular development proposals. They may be working on behalf of a developer in the quest for planning permission required before a project can go ahead, but they might also be working on behalf of a local authority, assessing a proposal once it has been submitted, or on the behalf of objectors trying to show that a particular development will be harmful. The range of projects can vary from something relatively small scale, like a small housing development in a field outside a village, to something very large, such as a new airport or high-speed railway line. Many countries have adopted a procedure called ‘environmental impact assessment’ (EIA) which obliges the promoters of particular classes of development to undertake a comprehensive review of any likely effects of the proposal and any steps that might be taken to mitigate them. The sorts of project covered by the European legislation on EIA includes such things as oil refineries, motorways, chemical works, open-cast mines, waste disposal sites, and quarries, but the list also includes large, intensive poultry farms.

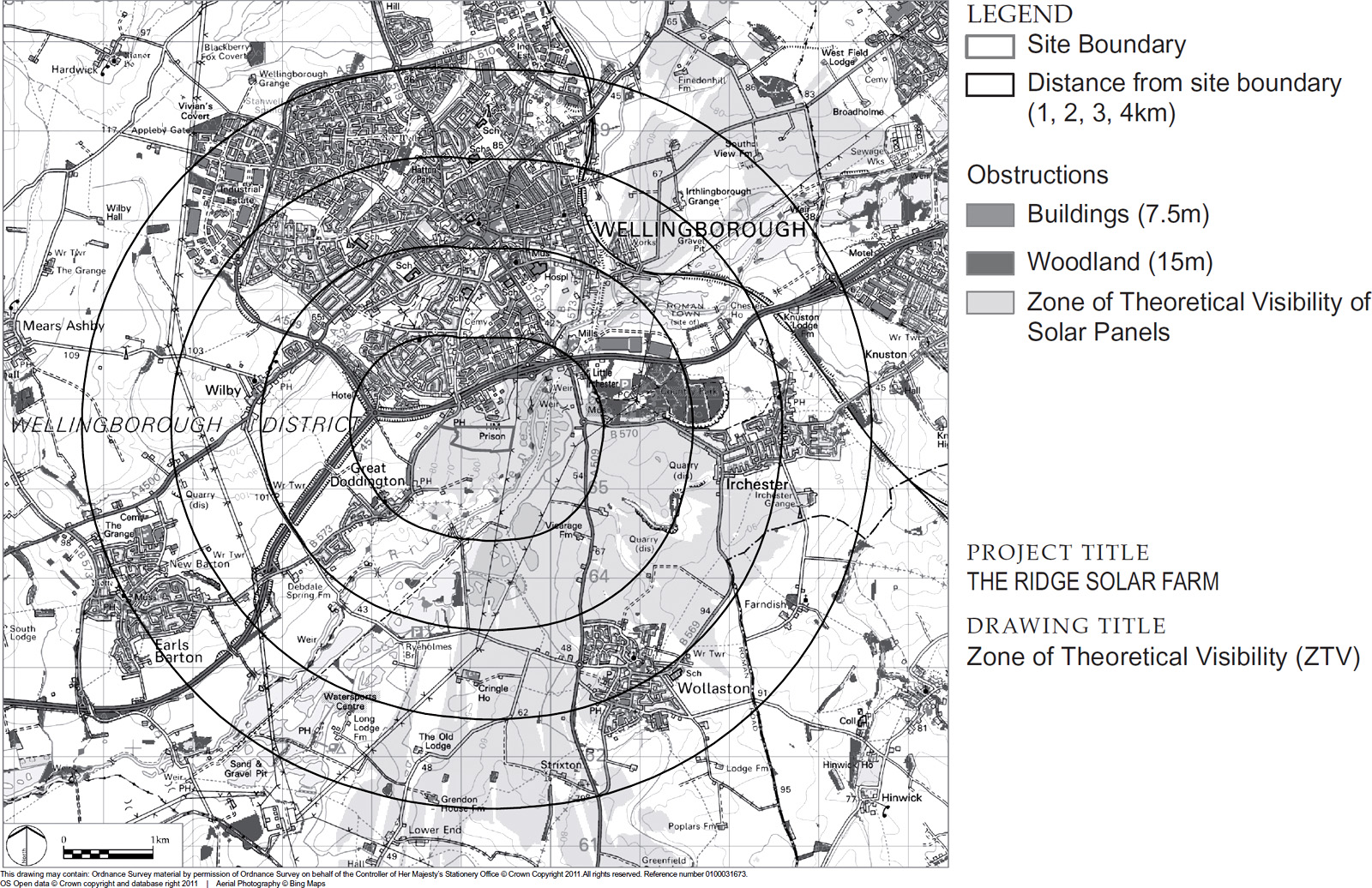

10. Zone of Theoretical Visibility plot for the Ridge Solar Farm near Wellingborough, prepared by Landscape Design Associates, 2013

EIA includes a separate but linked procedure called ‘landscape and visual impact assessment’ (LVIA) which looks at the possible effects of the development upon the physical landscape and upon views and visual amenity. LVIA is generally undertaken by landscape architects. It can, of course, be done for projects which do not require a full EIA. The virtue of carrying out these assessments early in the development process is that they can serve as design tools, identifying ways to avoid impacts or to reduce their scale. When assessing the visual impact of something like a wind farm or a new factory, the landscape architect used to go and stand on the site of the proposed structure and with map in one hand and pencil in the other, and try to map the area from which it could be seen. This would be supplemented by drawing sections based on map contours (Figure 10). There are now computer programs which enable this ‘zone of theoretical visibility’ (ZTV) to be estimated much more accurately. Visualization software can also provide reliable images of what a proposed development might look like from particular viewpoints. Problems can sometimes be avoided by reducing the scale of the development or by some adjustment of levels. Experience has shown that such measures are often more effective in mitigating impact than cosmetic landscape works such as the planting of trees to screen something deemed unsightly.

Green infrastructure planning

Urban green space tends to get taken for granted. People like it and sometimes pay a lot of money to live near to it, yet its maintenance is often one of the first things to be cut in times of austerity, and it tends to get nibbled away for both public and private projects. Every so often the case for green space needs to be articulated again, and the way in which the argument is presented usually reflects the preoccupations of the times. We live in an era when arguments made by economists hold enormous sway over public policy. If green space is perceived as little more than ornament, hard-headed accountants are likely to conclude that its upkeep is too much of a drain on the public purse. Hence the need for arguments which show that green space is useful and functional, that it ‘provides cross-cutting benefits across policy agendas’, and that it does something for us. The latest form this advocacy has taken is green infrastructure planning.

Green infrastructure planning builds upon the idea of ‘environmental services’ mentioned in Chapter 5. Many of the historical examples of park provision we have already considered could easily be reclassified in these terms. Olmsted said that Central Park would be ‘the lungs of the city’ and Boston’s Emerald Necklace, constructed from 1878 onwards, can be regarded as a successful green infrastructure project which delivered public health benefits from improved sewage treatment. Contemporary thinking classifies ecosystem services under a series of headings. There are ‘supporting services’ such as the creation of soils, which underpin all other services. There are ‘provisioning services’—the supply of necessities like food and fuel. There are ‘regulating services’ including the capture of carbon from the atmosphere. Finally, there are ‘cultural services’ which include all the ways in which nature contributes to human well-being. Here landscape plays a significant role, contributing aesthetic inspiration and enjoyment, a sense of history and place, recreational opportunities and spiritual elevation. Well planned green infrastructure can bring these benefits to people in densely populated urban areas. It can help to alleviate some of the problems caused by climate change: green spaces can, for example, be designed to retain large volumes of flood water and to help it to percolate into the ground, thus safeguarding built-up areas. A crucial idea is ‘multi-functionality’, the concept that many different functions or activities, ranging from water management, to habitat protection, to the provision of health enhancing outdoor recreation, can be provided by the same pieces of land.