Chapter 10

Landscape and urbanism

Though the word ‘landscape’ is often taken to be synonymous with ‘countryside’ or with ‘rural scenery’, the examples of landscape architectural work given throughout this book have shown that landscape architecture is an urban practice as much as a rural one. Indeed, I would go further and say that it is much more about what happens in and around towns and cities than it is about farmland or bucolic beauty spots. Landscape work is usually tied in some way to development, and most of this happens in urban areas. What is more, in the future most people are going to live in cities. According to the United Nations the percentage of the world’s population living in urban areas has already overtaken the percentage living in rural areas. This trend seems set to continue, so that by 2050 it is projected that 70 per cent of people will live in towns and cities. More and more people will live in ‘megacities’ which are defined as urban agglomerations with a population of over 10 million. Tokyo is currently the largest city in the world with a population exceeding 34 million. There were 16 megacities in 2000, but it is estimated that there will be 27 by 2025 and 21 of these will be in less developed countries. The rapid and largely unplanned expansion of cities during the Industrial Revolution was the spur to improvements in sanitation, housing standards, and the provision of urban parks. In the same way, the current spate of urbanization poses questions about the possible quality of life in such vast settlements, challenging landscape architecture and other disciplines concerned with the built environment to adjust to the scale of the megacity phenomenon.

Landscape architecture and urban design

The task of shaping liveable cities is so complex that it calls for contributions from a range of professionals, including landscape architects, building architects, and urban planners. Each of these disciplines has its own sensibilities, its own approach to training and education, and its own specialist knowledge. A landscape architect, for example, should know which species are the best street trees and how to plant them in sidewalks stuffed with sewers, gas mains, and fibre-optic cables, but an urban planner might have a better grasp of residential densities or the relationship between travel patterns and built form. One of the strengths which landscape architecture characteristically brings to urban issues is an advanced understanding of natural systems and ecology. In the late 1950s there was already a growing conviction that the problems presented by cities, particularly in the age of the automobile, required a pooling of expertise—and a series of conferences held at Harvard University attempted to find a common basis for a new discipline called urban design. This discipline is now well established in its own right and there are numerous university programmes, generally at post-graduate level, to prepare practitioners to work in this field. Yet, unlike landscape architecture or planning, urban design is not a profession with formal accreditation procedures and the accompanying institutional paraphernalia. Although this can be liberating, it also means that to practice as an urban designer one generally also needs to be qualified in one of the related professions—perhaps landscape architecture.

Unsurprisingly, considering how urban design came into being, there are significant overlaps between urban design and landscape architecture. We can return again to Olmsted’s practice, a lot of which might now be classified as urban design as much as it was landscape architecture. Planning a city neighbourhood involves designating and designing parks and open spaces, as well as housing areas, shopping centres, and transport systems. Olmsted’s park systems, as we have seen, solved problems of urban sanitation as well as providing places for recreation. Designing a park necessarily involves an understanding of its context, its position in the urban fabric, its relationship to the places where people live and work, its connections to streets as well as to other open spaces, and the ways in which residents and visitors to the city are likely to use it.

The differences between landscape architecture and urban design are largely a matter of perspective. This became clear to me when running joint studios for landscape architecture and urban design students. When presented with the same urban site, usually an existing open space or land reclaimed from derelict industry, the urban designers’ inclination was to fill it with buildings, amongst which would be a scattering of small parks and urban squares. The landscape architecture students tended towards the opposite direction, scattering a few buildings amid large tracts of open space. The urban designers tended to see green open space as ornament and occasional relief, missing the functional and ecological benefits of larger parks and connected greenspace systems. The landscape architects, conversely, lacked confidence in dealing with built form, and at worst their designs did not seem to belong to a city. The purpose of such joint studios, of course, is to overcome these blinkered perceptions and to become aware of what other disciplines have to offer. Landscape architects need to be aware of the economics of urban development, for example, but need not be experts in them. Urban designers ought to understand the potential of green infrastructure, but can safely leave its implementation to landscape architects.

Suburbanization, sprawl, and many varieties of urbanism

There is a strong connection between transport systems and urban form. Back in the 1930s there was already an outcry in Britain about ‘ribbon development’ along trunk roads and the way this was joining towns together and harming the aesthetics of the countryside. Uncontrolled development was seen to be devouring pleasant scenery. In America, where land was plentiful and gasoline was inexpensive, the extension of large suburban zones around original downtown districts was labelled ‘sprawl’. Despite the apparent consumer preference for and aggressive marketing of suburban lifestyles, sprawl was condemned by most architects, landscape architects, and planners. It has frequently been linked to a host of social and environmental ills. Suburbs are thought to lack the vibrancy and sociability of traditional neighbourhoods, while encouraging a dependency on the car which promotes unhealthy lifestyles and an epidemic of obesity. America is also the world’s largest per capita emitter of carbon dioxide, something which has also been linked to low-density living and a love-affair with the automobile. The vision of spacious living promoted by Thomas Jefferson and William Penn has turned out to have serious repercussions.

There have been many responses to the issue of sprawl, many of which share salient features. The earliest was New Urbanism, an urban design movement which opposed the dispersion and atomization of communities by seeking to recreate a lively civic realm and a strong sense of place. It emerged in the 1980s drawing upon the urban visions of architect Leon Krier (1946–)and the ‘pattern language’ of the theorist Christopher Alexander (1936–), both of whom advocated a return to time-honoured ways of building cities derived from Europe. It advocated walkable neighbourhoods, often centred upon a park or an urban square. Narrow streets, some lined with trees, would discourage traffic and all the components of a liveable town—schools, nurseries, play areas, and shops—would be easily reached on foot. Stylistically the movement tended to be conservative and backwards-looking, seeking to replicate traditional styles of building. Two of the best known examples of New Urbanist inspired developments are Poundbury, on the outskirts of Dorchester, UK, and Seaside in Florida, but critics have found an ersatz quality in these places, which is perhaps why Seaside was selected as the location for The Truman Show (1998) a film in which the central character unwittingly lives a near-perfect, artificial life, manipulated by the production team of a television programme. Next there came ideas of ‘smart growth’, the ‘compact city’, and ‘urban intensification’, all of which retained New Urbanism’s ideas about pedestrianized urban centres, without its nostalgic yearning for the 19th-century European city. Characteristic of such approaches are the provision of a range of housing choices, well integrated mass transport systems, mixed land uses, and the preservation of farmland, urban greenspace, and environmentally significant habitats. It is clear that landscape architects have a large role to play in the realization of such a vision. This way of thinking has been very influential in several European countries, particularly the UK and the Netherlands.

Transport and infrastructure

The trams in Barcelona, Strasbourg, and Frankfurt glide charmingly between avenues of trees, along ribbons of mown grass. These are stunning examples of efficient public transport systems seamlessly combined with attractive landscape design. Examples abound of landscape architects working with engineers to humanize transport infrastructure. In Lund, Sweden, landscape architect Sven-Ingvar Andersson (1927–2007) transformed a linear space along a railway line by laying sett paving and planting linden trees to create a pedestrian mall. On a larger scale, the Dutch practice West 8 has systematically planted thousands of birch trees in the spaces around and between Schiphol airport’s runways and buildings—the species was chosen not just for the beauty of its bark, but because it is not attractive to perching birds and thus no threat to aeroplanes. In many instances, transport infrastructure can also become part of green infrastructure. Green transport corridors can be particularly valuable in linking together ecologically valuable patches of habitat within the urban matrix. Sometimes, when roads or railways would serve to divide, landscape architects are able to provide a remedy in the form of green bridges which connect habitats on either side.

The examples given in the last paragraph are cases of tactical interventions to turn elements of transport infrastructure into amenable places, but there is a broader, more strategic sense in which transport systems shape cities. A well-known example is ‘Metroland’, the swathe of suburbs that were built to the north-west of London in the early 20th century, served and facilitated by the Metropolitan Railway. The celebrated Copenhagen ‘Finger Plan’ of 1947 outlined a strategy whereby the city would be developed along five radiating commuter train lines (the ‘fingers’) extending from the dense urban centre (the ‘palm’), but between these would lie wedges of greenspace for agriculture and recreation. As is so often the case, the pattern of the transport network, the built form of the city, and the structure of the open space system were intimately linked. Recognizing these linkages provides tools for urban planning. Despite design codes and zoning regulation, there is much about the growth of cities which must be left to the market, often to the chagrin of planners and urban designers. However, the expenditure of public money on infrastructure projects and on urban greenspace is politically accepted, even in the most capitalist economies, so here there is often scope to shape the city for the common good, or at least in those societies where infrastructure precedes development. In the case of the informal settlements which are so much part of the megacity, the situation is rather different, though public funds can be provided for the retrofitting of infrastructure, open space, and services in places which sprang up without them.

Landscape urbanism and ecological urbanism

Just as debates at Harvard preceded the formation of urban design as a discipline, a conference at the University of Illinois, Chicago, in 1997 promulgated a new ism called ‘landscape urbanism’, a name coined by Charles Waldheim, who is now Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design. In the words of James Corner, Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, this new ‘way of thinking and acting’ has been made necessary by ‘the failure of traditional urban design and planning to operate effectively in the contemporary city’. This sense of failure seems to stem from consideration of the way American cities have continued to sprawl horizontally, from astonishment at the speed with which megacities have grown in developing countries, and from the new phenomenon of the hollowing out of older industrial cities once the businesses that were their lifeblood close or relocate. This process is exemplified by Detroit, no longer the ‘Motor City’ but now an urban landscape represented by images of derelict factories and ruinous grand hotels. In all of these situations, the landscape urbanists argue, the urban planner is powerless, and the only thing left which can link a city together is its landscape. One way of conceptualizing this would be to say that the focus of attention has shifted from buildings as the basic blocks of the city to landscape as the glue or the medium which binds everything together. In a way which parallels the emergence of urban design, landscape urbanists do not propose the formation of a new profession, but suggest that the conceptual fields of such disciplines as landscape architecture, civil engineering, urban planning, and architecture need to be integrated. Master’s programmes in landscape urbanism sprang up at several North American universities and at the Architectural Association in London.

Just how innovative landscape urbanism might be and the extent to which it is a reworking of time-served ideas from the landscape architecture tradition have been topics of much discussion. One of the tenets of landscape urbanism is that it is more important how a landscape functions—what it does for us—than how it looks. This is very similar to the ideas expressed by advocates of green infrastructure planning, but as I have argued in this book, a concern for functionality was a notion present at the very beginning of landscape architecture, in the work of Olmsted and his successors. Landscape urbanists would probably agree, but where they controversially take issue with the Olmstedian tradition is with its advocacy of rus in urbe, the inclusion of Romanticized nature in the city. This is rejected as at best an irrelevance or at worst a kind of camouflage or deceit. They go further and argue that the way we speak about landscape on the one hand and cities on the other is conditioned through a ‘19th-century lens of difference and opposition’. They wish to argue that we should do away with the binary distinction between the urban and the rural. They would like us to recognize that the city’s footprint extends well into what we would traditionally call the countryside, and that the latter is organized to provide resources for the city, whether food, drinking water, or energy. At the same time, voids within the city, such as those created by the demise of an industry or areas associated with essential items of infrastructure, are opened up to natural processes such as ecological succession. Ever since the advent of Deconstruction as a literary and philosophical movement, it has been fashionable in academic circles to attack binary oppositions, but I would argue that many binaries, including this one, are quite useful and that the consequence of abolishing the distinction between countryside and town would be to strengthen the tendency towards sprawl and put at risk cultural landscapes adjacent to cities. Sometimes the rhetoric of landscape urbanism favours ‘going with the flow’ even if that means our cities will become radically decentred, rhizome-like networks, spread wide across the landscape. Yet it was concern about ‘ribbon development’ that led in Britain to planning laws and green belts to contain urban expansion. Unbridled capitalism and unchecked sprawl do not have to hold sway. Sometimes good city planning means redirecting, slowing, or stopping things from happening.

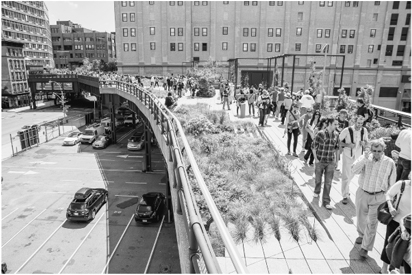

On the other hand, there are many ideas within landscape urbanism which have great merit. Landscape urbanists like to take the long view, recognizing that sites and cities develop over time. In Corner’s writing there is an emphasis upon preparing ‘fields for action’ or ‘stages for performances’—phrases which are vague enough to refer either to the physical works such as the clearance of derelict buildings or to more abstract activities such as assembling parcels of land from different ownerships, raising funding, gaining various permissions, and so on, in order to allow things to happen with some degree of spontaneity. In place of fixed masterplans, landscape urbanism extols a flexible indeterminacy. Landscape urbanists write in praise of the sorts of urban gardening and agriculture that have sprung up on vacant land in Detroit. There is also a championing of neglected places, the left-over land and interstices between motorways, pipelines, sewage farms, railway sidings, and landfills. One project often referenced is the Parc de la Trinitat in Barcelona (1993), a park and sports complex tucked inside a looping highway interchange by designers Enric Batlle and Joan Roig. Equally celebrated is the more recent High Line in New York City (2005–10), where Corner’s practice, Field Operations, collaborated with architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro to transform an abandoned elevated freight railroad on Manhattan into a linear park incorporating planting inspired by the self-seeded vegetation which had colonized the structure during many years of disuse (Figure 11).

We could add to this list of virtues by mentioning landscape urbanism’s interest in making positive use of waste materials. In his book Drosscape Alan Berger, Associate Professor of Urban Design and Landscape Architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, argues that all cities produce waste, but that this is something which can be scraped, shaped, surfaced, and reprogrammed to fulfil socially and environmentally useful purposes. Berger has written that ‘the challenge for designers is thus not to achieve drossless urbanisation but to integrate inevitable dross into more flexible aesthetic and design strategies’. Field Operations’ long-term involvement in transforming the Fresh Kills Landfill (2001–40) into what will eventually become New York’s largest park is thus acclaimed as a beacon of landscape urbanist practice. Conceivably it has been necessary to push such arguments about the usefulness of waste land harder in North America, where historically the land supply has not been limited, than in crowded Europe, where land is tight and traditions of land reclamation grew out of the need to deal with war-damaged cities after the Second World War.

11. James Corner’s landscape architecture practice, Field Operations, collaborated with architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro to transform an abandoned elevated freight railroad on Manhattan into the popular High Line linear park (2005–10)

Landscape urbanism has been a deliberate and useful provocation. To hear the landscape described as ‘machinic’, to talk about dismantling the boundaries between disciplines, to think at vast physical and temporal scales, to downgrade or even dismiss the importance of aesthetics … these moves and others have had their desired effect, stimulating shifts in practice, new ways of conceptualizing urban issues and new approaches to imagining solutions. It was never intended to replace landscape architecture; one can be a landscape architect and a landscape urbanist, indeed it is important that those who enter the nexus of landscape urbanism bring with them their own specialist knowledge and skills. But landscape urbanism’s arc as the radical idea of the moment is almost complete. Charles Waldheim suggested in 2010 that landscape urbanism had entered a ‘robust middle age’ which was a bit of a surprise for those outside America who were only just encountering it. In 2009, Harvard University held another conference, this time on the theme of ecological urbanism, an expansion of the landscape urbanist idea led by Mohsen Mostafavi, Dean of the Graduate School of Design. Whether the world is ready for yet another ism before the sun has set on the last one is a moot point, but the newcomer has retained many of the ideas which informed its predecessor, including the need for the design disciplines to respond to the scale of the ecological crisis which confronts us all. It calls for new ways of planning future cities as well as retro-fitting existing ones, and it seems to have ditched some of the more strident and off-putting aspects of landscape urbanism, including its impenetrable jargon. It is clear, though, that the values and perspectives of landscape architecture will continue to be central to this new movement. Landscape architects have been ecological urbanists for a very long time.