2

Grievances, Agendas, and Methods

THE CAUSES OF World War II were many. Age-old border and national grievances sparked tensions. There was not just general unhappiness of both the winners and losers of World War I over the Versailles Treaty that had supposedly ended the conflict and established a lasting peace, but also real furor at a settlement variously labeled as either too soft or too hard—and increasingly seen on all sides as unsustainable.

Neither of the prior two German wars—the Franco-Prussian War and World War I—had solved the perennial problem of a unified, dynamic, and nationalist Germany in the heart of Europe. And by the 1930s these tensions were energized by twentieth-century fascist technologies and ideologies. The result was a veritable fantasyland that grew up in the late 1930s in both Europe and Asia, in which citizens of the intrinsically weaker Axis powers, both industrially and technologically, were considered supermen, while real Allied supermen lost their confidence and were despised by their enemies as unserious lightweights.

What followed was the central tragic irony of World War II: the weaker Axis powers proved incapable of defeating their Allied enemies on the field of battle, but nevertheless were more adept at killing far more of them and their civilian populations. World War II is one of the few major wars in history in which the losing side killed far more soldiers than did the winners, and far more civilians died than soldiers. And rarely in past conflicts had the losers of a war initially won so much so quickly with far less material and human resources than was available to the eventual winners. In sum, World War II started in a bizarre fashion, progressed even more unpredictably, and, in the technological sense, ended in nightmarish ways never before envisioned. The shock of the war was not just its historic devastation and brutality, but that such unprecedented savagery appeared a logical dividend of twentieth-century technology and ideology—a century in which enlightened elites had promised at last an end to all wars, and shared global peacekeeping as well as new machines and customs to make life wealthier, more secure, and more enjoyable than at any time in history.

WORLD WAR II is generally regarded to have begun on September 1, 1939. Germany invaded Poland—for the third time in seventy years crossing the borders of its European neighbors. Hitler’s aggression prompted a declaration of war on Germany by Britain two days later. Most of the British Empire and France joined in, at least in theory. Seventeen days later, the Soviet Red Army, assuming that it would not be fighting Japan simultaneously, entered Poland to divide the spoils of this ruined and soon-to-disappear nation with Nazi Germany.1

The later Axis of Germany, Italy, and Japan had participated in small wars prior to September 1939 in Spain, Abyssinia, and Manchuria. But none of those aggressions—nor even the Nazi 1938–1939 absorption of much of Czechoslovakia—had prompted a collective military response from the European democracies. Throughout history larger states have more frequently blamed their smaller and often distant allies for entangling them in wars than they have rushed to prevent or end those wars. In 1938 few in Paris or London had wished to die for Czechoslovakia, or to stop the Axis agenda of incrementally absorbing borderlands far from the Western capitals. In September 1939 few wanted to fight for Poland—at least if they believed that the war itself would end with the end of Poland. The Soviet ambassador to Britain, Ivan Maisky, recorded a conversation in November 1939 he had with Lord Beaverbrook, who illustrated British fears just ten weeks into the war: “I’m an isolationist. What concerns me is the fate of the British Empire! I want the Empire to remain intact, but I don’t understand why for the sake of this we must wage a three-year war to crush ‘Hitlerism.’ To hell with that man Hitler! If the Germans want him, I happily concede them this treasure and make my bow. Poland? Czechoslovakia? What are they to do with us? Cursed be the day when Chamberlain gave our guarantees to Poland!”

If recorded accurately, Beaverbrook’s words were in fact not that different from Hitler’s own initial feelings about Britain, which, he felt, should have stayed out of a European land war, kept its empire, and made a deal with the Third Reich about their respective hegemonies: “The English are behaving as if they were stupid. The reality will end by calling them to order, by compelling them to open their eyes.” Being neutral is by design a choice, with results that either harm or hurt the particular belligerents in question—with neutrality almost always aiding the aggressive carnivore, not its victim. Or as the Indian statesman and activist V. K. Krishna Menon cynically once put it, “there can be no more positive neutrality than there can be a vegetarian tiger.”2

Still, Hitler was for a moment dumbfounded—“unpleasantly surprised,” in the words of Winston Churchill—that the supposedly enfeebled Allies had at least nominally declared war over Poland. It was natural that Hitler should be taken aback, given the fact that his new nonaggression pact, signed with the Soviet Union on August 23, 1939, had eliminated, he had hoped, the specter of a World War I–like, two-front continental war. After all, Poland’s fate had always been to be divvied up, given that it had been partitioned on at least four previous occasions. Hitler soon recovered as he sensed that even though the Allies had declared war, there was little likelihood that they would ever wage it wholeheartedly. Moreover, Hitler envisioned something different for Poland: not just a quick defeat, but the “annihilation” of the state altogether in a manner that would be “harsh and remorseless.” Poland would disappear before the dithering Allies could do much about it, and would teach them of the unpredictable nihilism of the Third Reich.3

Yet the duplicitous German and Russian attack on Poland, digested over the ensuing eight months of occupation, slowly did change ideas of going to war in France and Britain. Poland’s quick end was seen as the final provocation in a long series of Hitler’s aggressive acts that had left the Western enemies of Germany deeply angered but also abjectly embarrassed and terribly afraid. For the shamed Western Europeans who were for a time snapped out of their lethargy, Hitler’s stopping at Poland in September 1939 was suddenly seen to be as unlikely as the earlier beliefs that the Nazis would have ceased their aggressions after Germany’s 1938 annexations of Austria or the Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia’s German-speaking areas bordering Germany and Austria. Certainly, Hitler had an agenda that transcended even that of the Kaiser’s and that could not be accommodated through concessions and diplomacy. The combined invasion of Poland also destroyed the unspoken democratic assumption that the evils of Nazism nonetheless would prove useful in shielding the West from the savagery of Russian Bolshevism. If Hitler had now made arrangements with the Soviet Union, then little was left of the amoral realpolitik that had excused Nazi brutality in exchange for keeping Stalinism away from the Western democracies.4

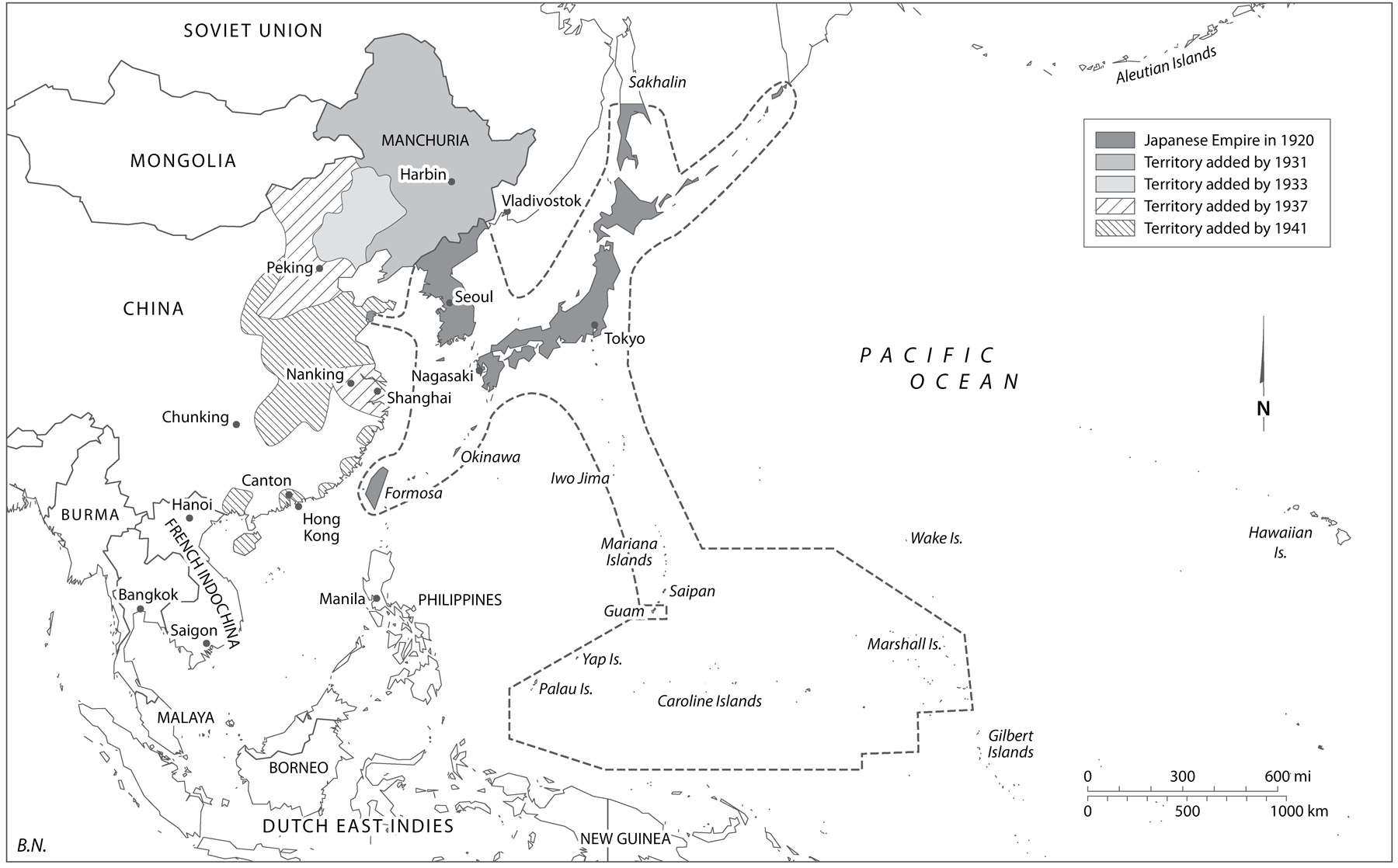

Growth of the Third Reich, 1933–1941

Hitler went to the trouble of dropping leaflets over Britain to convince the British not to see the loss of Poland as a legitimate cause to pursue their declared war against Germany. But the potential for a wider war was already looming. Aside from the pivotal global role of the British Empire, there were soon alliances with, and enemies against, Germany on several continents—Australia, Asia, North America, and eventually South America. Nations declared war on one another without full appreciation of the long-range potential of any of them to conduct a world war. This time around, the conflict grew far wider and far more deadly than in 1914, in part because the war of 1939 soon transcended the nineteenth-century European problem of containing the continental agendas of a dynamic, united, and aggrieved Imperial Germany, and technology had reduced both time and space. The new war after 1941 involved the political futures of hundreds of millions, far beyond the paths of the Rhine and Oder, and on all the continents, as battles on rare occasions reached the Arctic, Australia, and even South America. At one time or another, most of the world’s greatest cities—Amsterdam, Antwerp, Athens, Berlin, Budapest, Leningrad, London, Moscow, Paris, Prague, Rome, Rotterdam, Shanghai, Singapore, Tokyo, Vienna, Warsaw, and Yokohama—could be reached by either bombers or armor, and were thus either bombed or besieged. By 1945 almost every nation in the world, with only eleven remaining neutral, was involved in the conflict.5

A STRANGE CONFLUENCE of events had not made the prewar reality of German, Italian, and Japanese collective weakness clear to the Allied powers until perhaps late 1942, after the victories at Stalingrad, El Alamein, and Guadalcanal. That was some time after Adolf Hitler—then Benito Mussolini, and finally the Japanese militarists led by Hideki Tojo—had foolishly gambled otherwise in Russia, the Balkans, and the Pacific, earning the odd Allied alliance of common resistance against them. The Germans and Italians had cheaply earned the reputation of immense power by intervening successfully against a weak Loyalist army in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). They had showcased their late-model planes, artillery, and tanks—rightly seen as cutting-edge in the late 1930s but rarely acknowledged as near obsolete by 1941. Their power seemed to have illustrated to the world a desire to use brute force recklessly and to ignore moral objections or civilian casualties. Franco’s Nationalists had won. The Loyalists, backed mostly by the Soviet Union and by Western volunteers, had lost.6

The Axis paradigm, at least in terms of infrastructure and armaments, seemed initially to have survived the Great Depression better than had the democracies of Western Europe and, in particular, the United States. In truth, America, for all its economic follies, had probably done as well as Germany in combatting the Depression, even though Hitler’s showy public works projects received far more attention. Confident Axis powers boasted of a new motorized war to come on the ground and above. This gospel seemed confirmed by a parade to Berlin of visiting American and British military “experts,” from aviator Charles Lindbergh to British tank guru J.F.C. Fuller. Most were hypnotized by Nazi braggadocio and pageantry rather than examination of precise armament output and relative quality of weapons. Few guessed that the hugely costly Nazi rearmament between 1934 and 1939 had nearly bankrupted the Third Reich but still had not given it parity in heavy bombers or capital ships with its likely enemies.

Mussolini and Hitler were far more frenzied leaders than those in Western Europe and America, and were able to feign a madness that was a valuable asset in prewar geopolitical poker. Both were wounded and bemedaled combat veterans of World War I from the enlisted ranks. A generation later, they now posed as authentic brawlers more willing to fight than their more rational Western Allied counterparts, who were led by aristocrats of the 1930s who had either been administrators or officers in the First World War. The antitheses were reminiscent of the historian Thucydides’s warning about the insurrection on the island of Corcyra, where the successful “blunter wits” were more ready for prompt action than their more sophisticated opponents.7

By the 1930s, the aftermath of the so-called Great War had given birth to a sense of fatalism among the generation of its noncommissioned veterans. In almost all of Hitler’s nocturnal rantings, he invoked the realism of the trenches of World War I, but in terms in which that nightmare steeled character rather than counselled caution. His lessons were quite different from the surrealism and occasional dark absurdity of Guillaume Apollinaire, Wilfred Owen, and Siegfried Sassoon, whose antiwar work found far larger international audiences than did that of their German counterparts. Perhaps more philosophical victors could afford to reflect on the war in its properly horrendous landscape; dejected losers by needs both romanticized their doomed bravery and found scapegoats for their defeat.

To the extent that they were prepared, the Allies for much of the 1920s and early 1930s seemed resigned, at least tactically, to refight the return of another huge slow-moving German army. They feared a future conflict as another mass collision of infantries plodding across the trenches (a conflict they had nonetheless won). As a result of such anxiety, the reconstituted allied powers in theory sought solutions to the Somme and Verdun in mobility and machines to avoid a return of the trenches. In reality, the preparations of those nations closest to Germany, such as France and Czechoslovakia, were more marked by reactionary static defensive fortifications. Concrete was impressive and of real value, but antithetical to the spirit of the mobile age and the doctrine of muscular retaliation. A geriatric French officer class and lack of tactical innovation and coordination meant that even had the Germans’ main thrust targeted the concrete fortifications of the Maginot Line, it might well have succeeded.

The Depression-era democracies were also without confidence that their industrial potential would ever again be fully harnessed, as it had been in 1918, to produce superior offensive weapons in great numbers. The 1920s were a time for finally enjoying the much-deserved peace dividend, not for more sacrifices brought on by rearmament that could only lead to endless war with the same European players. Luftwaffe head Hermann Goering scoffed to the American news correspondent William Shirer in Berlin in November 1939, just two months after the invasion of Poland, “if we could only make planes at your rate of production, we should be very weak. I mean that seriously. Your planes are good, but you don’t make enough of them fast enough.”

Goering typically was quite wrong, but his errors at least reflected the German sense that the Allies had lost the power of deterrence, which is predicated not just on material strength but the appearance of it and the acknowledged willingness to use it. Even today, few note that French, British, and American plane production together in 1939 already exceeded that of Italy and Germany. The British were already flying early Stirling (first flight, May 1939) and Handley Page (first flight, October 1939) four-engine bomber prototypes, and the Americans were producing early-model B-17s (delivered as early as 1937). These antecedents were slow and sometimes unreliable (especially the British aircraft), but they gave the Allies early pathways to the use of heavy bombers that would soon be followed with improved and entirely new models. Most important, Allied aircraft factories were already gearing up to meet or exceed German fighter and bomber designs, even before America entered the war. Later the delusional Goering himself would deny that Allied fighter escorts could ever reach German airspace—at a time when they were routinely flying through it and were occasionally shot down inside the Third Reich.8

No matter. Almost every public proclamation that the Allies had voiced in the 1920s and early 1930s projected at least an appearance of timidity that invited war from what were still relatively weak powers. For the decade after Versailles, France, Britain, and the United States scaled back their militaries. All sought international agreements—the Washington Naval Conference (1921–1922), the Dawes Plan (1924), the Locarno Treaties (1925), the Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928), and the London Naval Conference (1930)—to tweak the Versailles Treaty, to limit arms on land and sea, to pledge peaceful intentions to one another, to showcase their virtue, to profess invincible solidarity, and even to declare war itself obsolete—anything other than to rebuild military power to shock and deter Germany. The prior victors and stronger powers yearned for collective security in the League of Nations; the former losers and weaker nations talked about unilateral action and ignored utopian organs of international peace. Democratic elites reinterpreted the success of stopping Germany and Austria in World War I as an ambiguous exercise without true winners and losers; Germans studied how clear losers like themselves could become unquestioned winners like their former enemies.

By the late 1920s, the victors of World War I were still arguing over whether the disaster had been caused as much by renegade international arms merchants as by aggressive Germans. Profit-mongering capitalists, archaic alliances, mindless automatic mobilizations, greedy bankers, and simple miscalculations and accidents were the supposed culprits—not the inability in 1914 once again to have deterred forceful Prussian militarism and German megalomania. British and French statesmen dreamed that Hitler might be an economic rationalist, and that new trade concessions could dampen his martial ardor. Or that he might be a realist who could see that a new war would cost Germany dearly. Or they downplayed Nazi racialist ideology as some sort of crass public veneer that hid logical German agendas. Or they saw Hitler as a useful—and transitory—tool for venting the frustrations of soberer German capitalists, aristocrats, and the Junker class. Or they believed National Socialism was a nasty but effective deterrent to Bolshevism.9

Consequently, when Chancellor Hitler acquired absolute power and was ratified as Führer on August 29, 1934, Allied statesmen assumed that the Germans would soon tire of their failed painter and Austrian corporal. Elites sometimes equate someone’s prior failure to gain social status—or receive a graduate degree or make money—with incompetence or a lack of talent. Yet the pathetic Socialist pamphleteer and failed novelist Benito Mussolini, and the thuggish seminary dropout, bank robber, and would-be essayist Joseph Stalin—traditional failures all—proved nonetheless in nihilistic times to be astute political operatives far more gifted than most of their gentleman counterparts in the European democracies of the 1930s. The British statesman Anthony Eden lamented that few in Britain had ever encountered anyone quite like Hitler or Mussolini:

You know, the hardest thing for me during that time was to convince my friends that Hitler and Mussolini were quite different from British business men or country gentlemen as regards their psychology, motivations and modes of action. My friends simply refused to believe me. They thought I was biased against the dictators and refused to understand them. I kept saying: “When you converse with the Führer or the Duce, you feel at once that you are dealing with an animal of an entirely different breed from yourself.”10

The Western democracies at first failed to appreciate the extent to which Hitler’s string of earlier spectacular diplomatic successes and easy initial blitzkrieg victories enthralled a depressed German people proud of a profound artistic and intellectual heritage. Cultured as they might have been, millions of the Volk saw no contradiction between High Culture and the base tenets of a National Socialism that steamrolled its opponents. Or, if anything, perhaps they sensed a symbiosis between the power of the German armed forces, the Wehrmacht, and the supremacy of Western civilization, as Hitler himself often ranted about opera, art, and architecture as the fruits of his victories deep into the night to his small, captive dinner audiences.

Panzer commander Hans von Luck related just such a cultural-military intersection, even during the dark December 1944 German retreat from the old Maginot Line on the French border. As Luck walked among the ruins of a bombed-out church, in the heat of battle, he suddenly saw an organ, and immediately showed himself to be a soldier of culture and sensitivity. “Through a gaping hole in the wall we went in. I stood facing the altar, which lay in ruins, and looked up at the organ. It seemed to be unharmed. A few more of our men came in. ‘Come,’ I called to a lance-corporal, ‘we’ll climb up to the organ.’ On arriving above, I asked the man to tread the bellows. I sat down at the organ and—it was hardly believable—it worked. On the spur of the moment I began to play Bach’s chorale Nun danket alle Gott. It resounded through the ruins to the outside.” There was no apparent disconnect between fighting to protect National Socialist Germany and seeking to play Bach amid the wreckage of battle.11

EMOTIONS PUSH STATES to war as much as does greed. Materialists might argue that all three resource-starved Axis powers simply went to war for more natural wealth—ores, rubber, food stocks, and especially fuels. They wanted additional territory that belonged to someone else, usually someone weaker, in order to expand their influence and population beyond their recognized borders. Yet it did no good to point out to National Socialist leaders that Germany’s large population, robust industry, and relatively little damage from the Great War made it likely to resume its role as a European powerhouse even without, for example, incorporating Austria, the Sudetenland, and western Poland. Nor would Hitler believe by late August 1939 that the Third Reich was already in Germany’s best geostrategic position since its founding, with its largest population and territory since the birth of the German state. Germany had far more territory in September 1939 than it has today with a similarly sized population.

There was no longer a hostile Tsarist Russian Empire. There was no rivalry with an Austria-Hungary, no antagonistic and interventionist United States. France and Britain were both willing to compromise. Nazi Germany freely bought oil on the open market, often from North America. It had either renegotiated or reneged on, without consequences, any international agreement that it felt detrimental to its expansionist agenda. Germans were not starving. Lebensraum (“we demand land and territory for the nourishment of our people and for settling our surplus population”) was not based on an existing shortage of arable land.12

Likewise, it would have been fruitless to point out that Japan did not need half of China to fuel its industries, or that the backward areas of East and North Africa were not the answer to Italy’s chronically weak economy. Instead, all three fascist powers resented, in varying degrees, and especially during the hard times of the early 1930s, the Versailles Treaty and its aftermath—especially that their honor had been impugned and their peoples had not received respect and commensurate deserts. They went to war to earn global power and especially to be recognized as globally powerful. The irrational proved just as much a catalyst for war as the desire to gain materially at someone else’s expense.

Japan and Italy nursed nagging grievances from 1919. As veterans of the winning side then, both now felt that they had not been rewarded with sufficient territorial spoils from Germany and Austria by the Big Power architects of the Versailles Treaty. Japan did not feel appreciated for its yeoman work of helping British naval forces in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and occasionally in the Mediterranean, and was not satisfied by the acquisition of a few German holdings in the Caroline, Marianas, and Marshall archipelagos. Italy did not see much territorial profit in gaining South Tyrol in the Alps, at least as compensation for its loss of nearly a million lives on the Austrian border in World War I. It viewed Versailles as proof of a “mutilated victory.”13

For all their bluster, the future Axis powers were anxious too. Germany remained deeply suspicious of the Soviet Union and of the Western democracies’ ability to hem it in with the global alliances, trade embargoes, and blockades. Italy feared the French and British navies: with eventual help from the Americans, both fleets might easily shut Mussolini out of his envisioned Roman imperial role in the Mediterranean. Japan was fearful of the omnipresence of the British and American fleets in the Pacific, which was seen as an affront to its sense of imperial self and its grandiose imperial agendas.14

If Hitler’s second greatest mistake—after the first of invading Russia in June 1941—was declaring war on the United States on December 11, 1941, it was for a few months understandable, given the still meager size of US ground forces on the eve of a global war that would inevitably involve a struggle for the European landmass. In Hitler’s fevered strategic calculations, he apparently assumed that after Pearl Harbor (according to Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, “the most important event to develop since the beginning of the war”) an underarmed America would have its hands full with the Imperial Japanese Navy. It would be unlikely even to find the ships to transport an entire army to Europe across submarine-infested waters.15

The advantages of sinking British-bound American convoys in the ensuing year 1942 were seen as worth the risk of tangling with the US Navy. America was now confronted with a two-front war. And if the United States had been content to watch Britain in flames, the end of France, and mass murder in China, it likely would not fight well if at all when faced with the specter of a Germany allied with Japan. In Hitler’s warped view of World War I, he never appreciated the miraculous efforts of the United States to have transported almost two million men to Europe in less than two years while producing an enormous amount of war materiel, despite being largely disarmed before 1917. As late as March 1941, Hitler had expressed no worries about serious US intervention in the war, given that America was at least “four years” away from its optimum production and had problems with “shipping.” Japan would whittle down the US fleet—or, even if Japan could not do so entirely, Fortress Europe nonetheless offered no friendly shores on which green American amphibious forces might land.16

No one, except a few German generals like Ludwig Beck, had dared to point out to Hitler the delusions on which such views were based. With a declaration of war on America, Hitler may have felt that at last he was to settle up with Jews worldwide. In any case, General Walter Warlimont claimed that Hitler scoffed at the idea of the United States as a serious enemy. America’s war potential “did not loom very large in Hitler’s mind. Initially, he thought very little of the United States’ capabilities.” Hitler did not grasp that by 1941 America had already begun to tap unused productive capacity from the Great Depression. Fifty percent of the US workforce was not fully employed during the 1930s, but easily could be if the nation were mobilized to confront a “total war.”17

HITLER’S GERMANY IN the late 1930s was seen by the democracies either as not much of an existential threat or as so great an existential threat that it would require another senseless war to stop it. While there were plenty of starry-eyed fans of fascism in the democracies of Western Europe and America, there were few vocal democratic zealots under the German, Italian, and Japanese tyrannies. It would have been unthinkable—and likely fatal—for German students in 1933 to proudly announce their collective unwillingness to fight for the newly installed Nazi government in the manner that the students of the Oxford Union had passed a resolution “that this House refuses to fight for King and Country.” The memoirist Patrick Leigh Fermor, who was at that moment aged eighteen, walking through Germany on his way from Rotterdam to Istanbul, noted of the vote:

I was surrounded by glaring eyeballs and teeth. Someone would shrug and let out a staccato laugh like three notches on a watchman’s rattle. I could detect a kindling glint of scornful pity and triumph in the surrounding eyes which declared quite plainly their certainty that, were I right, England was too far gone in degeneracy and frivolity to present a problem.… These undergraduates had landed their wandering compatriots in a fix. I cursed their vote; and it wasn’t even true, as events were to prove. But I was stung still more by the tacit and unjust implication that it was prompted by lack of spirit.18

Between the two wars, the European democracies—Britain especially, in which free expression thrived—sought to explain the horrors of the Great War within a general theory of Western erosion. British and French literature reflected the pessimism of national decline and civilizational decadence, and saw rearming as reactionary and coming at the expense of achieving social justice. We now talk generally of appeasement in the modern era, but it is difficult to grasp just how firmly embedded active pacifism was within the Western European democracies. In France during the 1920s, teachers’ unions had all but banned patriotic references to French victories (which were regarded as “bellicose” and “a danger for the organization of peace”) and removed books that considered battles such as Verdun as anything other than a tragedy that affected both sides equally. In the Netherlands, the few larger ships that were built were called a flottieljeleider (“flotilla leader”) rather than a cruiser, apparently to avoid the impression that they were provocative warships. As the French author Georges Duhamel put it, “for more than twelve years Frenchmen of my kind, and there were many of them, spared no pains to forget what they knew about Germany. Doubtless it was imprudent, but it sprang from a sincere desire on our part for harmony and collaboration. We were willing to forget. And what were we willing to forget? Some very horrible things.”19

Perhaps Horace Wilson, advisor to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, best expressed the mood of British appeasement in 1938–1939: “Our policy was never designed just to postpone war, or enable us to enter war more united. The aim of appeasement was to avoid war altogether, for all time.” Across the Channel, Germans had seen appeasement in a different light. Of the Anschluss, Germany’s forced annexation of Austria, Chancellor Franz von Papen later concluded, “not only had there been no armed conflict, but no foreign power had seen fit to intervene. They adopted the same passive attitude as they had shown toward the reintroduction of conscription in Germany and the reoccupation of the Rhineland. The result was that Hitler became impervious to the advice of all those who wished him to exercise moderation in his foreign policy.”20

In the late thirties Winston Churchill was playing the hand of the Athenian statesman Demosthenes, although a weaker one, in his warnings about Hitler—a far crueler despot than Philip II of Macedon. If there was squabbling in Britain and France over the inability of the Allies to stop Hitler’s serial provocations between 1936 and 1939, there was increasing unanimity inside Nazi Germany. Once-skeptical German generals, who had feared the endpoint of Hitler’s trajectory, were soon silenced by his seemingly endless and largely cost-free diplomatic successes.21

When the French did not move against Germany’s vulnerable western flank in September 1939, and when Prime Minister Édouard Daladier made it clear that Hitler, to achieve a peace, would have to give up most of his easy winnings in Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, and when the French and British could not win over the Soviet Union with either bribes, concessions, or appeals to common decency, a massive invasion of France was all but certain, but not necessarily irresistible. From the German performance in the Spanish Civil War to its annexation of Austria and its incorporation of the Sudetenland, the consequences of blitzkrieg were too often vastly exaggerated and falsely equated with inherent military superiority—a fact true even later of the so-so operations of the German military in Poland and Norway at the beginning of the war itself.

Most overly impressed observers ignored the fact that such lightning-fast German attacks were hardly proof of sustained capability. They were no way to wage a long war of attrition and exhaustion against comparable enemies, especially fighting those with limitless industrial potential across long distances, in inclement weather, and on difficult terrain. Few pondered what would follow once Germany ran out of easy border enemies or guessed that it would predictably have to send Panzers across the seas or slog in the mud of the steppes. That proved an impossible task for a nation whose forces relied on literal horsepower and had little domestic oil, no real long-range bombing capability or blue-water navy, and a strategically incoherent leadership. German blitzkrieg would never cross the English Channel. It would die a logical if not overdue death at Stalingrad in the late autumn of 1942.

Of all the services of the Wehrmacht, the air force should have been the most critical. In fact, it was the most incompetently led, by a cohort of energetic but mentally unstable grandees—most prominently the World War I veterans Hermann Goering, Erhard Milch, and Ernst Udet. The Luftwaffe hierarchy carved out bureaucratic fiefdoms that impeded aircraft production. For too long it was wedded to a bankrupt idea that bombers should focus on dive bombing. Luftwaffe commanders had designed a superb ground-support air force that could facilitate surprise attacks against small vulnerable states, but had not committed to creating a truly independent strategic arm. In a larger sense, the early Nazi war machine, like that of the Japanese, had grown confident in the prewar era that new sources of military power—naval air power, strategic bombing, and massed tank formations in particular—if used in preemptory fashion, could wipe out enemy counterparts and thus end the war before it had started. Even the new weapons and strategies of the Allies would cede the battlefield to the technological superiority and strategic sophistication of the Axis powers, rendering the greater industrial potential of the larger states immaterial.22

The Kriegsmarine—predicated on the idea that battleships might one day challenge Britain at sea (along with Admiral Doenitz’s insistence that U-boats could do what surface ships could not)—possessed not even a single aircraft carrier. It built just enough heavy surface ships to siphon off precious resources from the army and U-boat fleet, but not enough to pose a serious threat to the Royal Navy. Admiral Raeder illustrated the abyss between Hitler’s braggadocio and the military resources of the Third Reich: “There were 22 British and French battleships against our 2 battleships and 3 pocket battleships. The enemy had over 7 aircraft carriers; we had not one, as the construction of our Graf Zeppelin, though nearing completion, was stopped because the Air Force had not even developed suitable carrier planes. The allied enemy had 22 heavy cruisers to our 2, and 61 light cruisers to our 6. In destroyers and torpedo boats the British and the French, combined, could throw 255 against our 34.” Indeed, Germany started the conflict with not one heavy bomber. Its navy could deploy only five battleships. There were only fifty submarines that were ready for service, and only three hundred Mark IV tanks, the only German model comparable to most French or Soviet counterparts.23

Hitler, for all his talk of Aryan science, could not even brag that German researchers and industry had given him superior weapons on the eve of war. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was not markedly better than the British Supermarine Spitfire fighter. In 1939, the French Char B1 tank was better armed and armored than its German Mark I, II, and III counterparts; so was the lighter but reliable French Somua S35 (over 400 produced). Hitler had little idea that the Soviet Union had vastly more planes, tanks, and divisions than he did—and soon of a quality equal to or better than the Wehrmacht’s.24

Before August 1939, it was still more likely that if neutrals like the United States or even the Soviet Union were to intervene in the war, they would do so against Nazi Germany. Each might eventually bring to the war far larger and more diverse militaries than Germany, Japan, or Italy. The most widely read prewar prophets of new armored and air power—Giulio Douhet, J.F.C. Fuller, B. H. Liddell Hart, Billy Mitchell, James Molony Spaight, and Hugh Trenchard—were not German. Although France first turned for its security to massive border fortifications and dubious friendship pacts with the fickle Soviet Union and weak Eastern European states, finally it began to rearm. As early as 1930, the British ambassador to France supposedly confessed to André Maurois, the novelist and later veteran, why the British had not listened to the French worries over an angry and possibly ascendant Germany: “We English, after the war, made two mistakes: we believed the French, because they had been victorious, had become Germans, and we believed the Germans, through some mysterious transmutation, had become Englishmen.”25

The French army—the supposed bulwark of the West—with help from the other smaller European democracies and Britain, outnumbered German troops in the West. Yet the stronger France became, the more it seemed to fear using its assets even in a defensive war against Germany. A sense of dread had loomed since right after Versailles, when the always prescient Marshal Ferdinand Foch had warned, “The next time remember the Germans will make no mistakes. They will break through northern France and seize the Channel ports as a base for operation against England.”26

The future Allies understandingly were in no mood to sacrifice more of their youth so soon after the tragic losses of World War I. When stung by the growing realization that the Peace of Versailles had solved very little, the democracies resorted to charades. Perhaps they must not offend Benito Mussolini, given their need for his allegiance against Hitler. Anthony Eden quotes a pathetic diary entry of Neville Chamberlain weirdly blaming the Austrian Anschluss on Eden, who had resigned as foreign secretary, for supposedly alienating Mussolini—in a manner that his successor, the appeasing Lord Halifax, would never have: “It is tragic to think that very possibly this [the Anschluss] might have been prevented if I had had Halifax at the Foreign Office instead of Anthony at the time I wrote my letter to Mussolini.”27

Aside from the failure to recognize that past victory is a quickly wasting asset, some in Britain, France, and the United States privately felt that Germany had some legitimate grievances about the loss of territory from World War I. Japan—a member of the Allied councils in the aftermath of World War I—perhaps also had reasonable claims. Even by Western colonial reckoning, the Japanese, more so than distant European colonial powers, deserved the greater sphere of influence among their Asian brethren. Japan chafed under European condescension. So it quietly continued its efforts to establish a first-rate navy and trained superb naval aviators on the assumption that it would expand a new Pacific sphere of influence that would be protected by a fleet of aircraft carriers. In response, British and Americans continued to dream that such emulative peoples could hardly master Western technology and tactics.28

Such confusion ensured that should the Axis powers be content with their occupations and limit their annexations to just a few neighboring and weaker states—Abyssinia, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Manchuria, and Korea—then there would be no good reason to resort to another world war to stop them. The democracies wrongly believed that their laxity would be seen as magnanimity. Meanwhile, the Axis rightly interpreted Neville Chamberlain’s popular reference to Czechoslovakia as “a faraway country” as a window into democracy’s moral weakness.

Unfortunately, most British statesmen, including luminaries like Lord Halifax and David Lloyd George, Britain’s successful prime minister during the second half of World War I, privately were relieved by the Munich Agreement—forgetting Aeschylus’s truism that “oaths do not give credibility to men, but men to oaths.” As France later collapsed in early June 1940, a French newspaper publisher lamented to the American journalist A. J. Liebling how unnecessary was the imminent French defeat:

We spoke with no originality whatever of all the mistakes all the appeasers in the world had made, beginning with Ethiopia. We repeated to one another how Italy could have been squelched in 1935, how a friendly Spanish government could have been in power in 1936, how the Germans could have been prevented from fortifying the Rhineland in the same year. We talked of the Skoda tanks, built according to French designs in Czechoslovakia, that were now ripping the French army apart. The Germans had never known how to build good tanks until Chamberlain and Daladier presented them with the Skoda plant. These matters had become for every European capable of thought a sort of litany, to be recited almost automatically over and over again.29

“Our enemies are little worms,” Hitler supposedly would later scoff at Allied peacemaking efforts. “I saw them at Munich.” He apparently had read the well-intentioned naïf Neville Chamberlain accurately. Whereas Winston Churchill told the House of Commons on October 5, 1938, that Munich was “a defeat without a war,” at about the same time Anthony Eden recorded a conversation in which Prime Minister Chamberlain had apparently remarked to a British colleague right after Munich, “you know, whatever they may say, Hitler is not such a bad fellow after all.” Chamberlain and other grandees had been taken in for years by Hitler’s lies, all to the effect of convincing them that he spoke for a victimized people with legitimate grievances and that he abhorred war as much as did the democracies. In an interview with the British Daily Mail correspondent and Hitler aficionado George Ward Price in August 1934, Hitler had assured that “Germany’s present-day problems cannot be settled by war.… Believe me, we shall never fight again except in self-defense.”30

ALL NATIONS GO to war thinking that they can somehow win. Had Germany won World War I, of course, there would likely not have been a Second World War twenty-one years later. Only Germany’s defeat and the postwar settlement that failed to deal with the “German Problem” ensured a replay. Nonetheless, it is at first glance surprising that the German-speaking peoples believed so soon after an earlier and catastrophic defeat that the outcome of a second and eerily similar aggressive effort might turn out any differently. Why exactly was Hitler assured he could succeed where Kaiser Wilhelm II had failed?31

When Hitler initially went to war in 1939 against Poland, he did so confident that Germany this time around would be fighting only on one front at a time, and could cease the conflict unilaterally when its appetites were satiated. As a self-taught student of history, Hitler felt that he had proceeded, in an episodic and carefully circumscribed fashion, in direct opposition to Kaiser Wilhelm II’s past nightmare of recklessly incurring an immediate two-theater war. “Who says I am going to start a war like those fools in 1914?” Hitler sometimes bragged. Like Hannibal who thought he could reverse the verdict of the First Punic War, and like Hannibal’s Carthage, which had been defeated but not emasculated in 241 BC, so Hitler and the Third Reich were convinced that the second time around they would not repeat the strategic mistakes of an earlier generation.32

Later, Nazi Germany would eventually find itself in a conflict on both its borders and in the skies above the homeland that it could not win. But in 1939 Hitler at least had believed that his nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union and the facts of a temporizing France, an isolated Britain, and a still-neutral United States had ensured that this time around there would be only a single enemy to fight at a single time. In other words, Poland would prove a short, limited, and likely successful war, and would be followed periodically by other short border conquests. He was initially correct in nearly all of his assumptions. That over the course of the disastrous year 1941, the Third Reich unilaterally chose a three-front war with Britain, Russia, and the United States perhaps still meant for Hitler that the war against the Allied superpowers somehow was still a sort of one-front active war with the Soviet Union: Britain was quiescent on the ground in Western Europe, and the United States had its hands full with Japan.

Under the partnerships of the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936–1937, both the sea powers Japan and Italy were likely to flip to Germany’s side should it appear to be winning its war in Europe, especially at the expense of the British Empire. The old German-Austrian partnership would reappear. But this time the alliance was accomplished through the German forced annexation of Austria and the coercion of its old subordinate subject states. Hitler had other reasons to believe World War I would not repeat itself. True, Italy’s military assets were thought to offer only dubious advantage to a German-led alliance. But its Mediterranean geography was nevertheless a valuable asset not available in 1914. Benito Mussolini’s original model of the fascist state also inflated its importance, as did Rome’s iconic religious and historical resonance. So Germany had almost all its allies from World War I, and had also flipped new ones as well in Italy and Japan.

Hitler was inordinately impressed by the naval power of his two fellow Axis powers, as if the Mediterranean and the Pacific might become Axis lakes in a way inconceivable in World War I. He accepted that the German navy was far weaker in a relative sense in 1939 than it had been in 1914, and the so-called naval parity achieved by the Z-Plan (the Kriegsmarine’s ten-year agenda to create a huge fleet) was still nearly a decade away. At the beginning of the war a prescient Admiral Raeder lamented that his far-too-small surface fleet could do little against the British navy except “die with honor.” At a later point Hitler assumed that eventually the Japanese navy and its martial audacity could tie down both the European colonials and the United States in a Pacific slugfest. The fear of Soviet communism, or, after 1940, the allure of rich orphaned European colonies in the Pacific, or the resentment of serial British and American bullying—any or all would ensure Japan’s eagerness to fight alongside Germany.

Yet fighting a common enemy separately was not quite the same as fighting it in synchronized and complementary fashion. The use of the vaguer Axis rather than Allies to describe the German relationship with Italy and Japan was revealing. It is hard to cite major examples of any serious Japanese-Italian-German strategic coordination. General Warlimont of the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Supreme Command of the Armed Forces) confessed to a late 1942 agreement to coordinate with the Japanese: “This document was characterized by the same degree of deception and insincerity as had become the rule for relations with Italy. The OKW Operations Staff had no part in its drafting and did not even see it. Subsequent German-Japanese military contacts were limited to occasional visits by Japanese officers to German Supreme Headquarters.”

Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and minister of foreign affairs, lamented of the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 that “we were informed of the attack on Russia half an hour after German troops had crossed the eastern border. Yet this was an event of no secondary importance in the course of the conflict, even if our understanding of the matter differed from that of the Germans.” Ciano failed to note that Italy likewise gave Hitler no forewarning of its invasions of Albania and Greece, given that deception was the mother’s milk of tyrannies. One of the ranking German liaison officers with the Axis partners remarked, “Mussolini feeling himself poorly situated, attacked Greece through Albania without telling us anything in advance—an episode that developed into a major disaster.… When the Italian adventure led to disaster, it was the Germans who had to pull Mussolini’s chestnuts out of the fire in the Balkan operations, which were a drain on us for the rest of the war.” Likewise, the Pearl Harbor attack caught Germany off guard; without it, Hitler might never have declared war on the United States. Hitler thought he had learned the lessons of World War I, but soon only amplified its mistakes by setting a model of arrogant deceit that was emulated by his equally arrogant and deceitful allies.33

OVER ITS TWENTY-YEAR lifespan, the Versailles Treaty of 1919 had been systematically violated by Germany and psychologically orphaned by the British, French, and Americans. Like the Treaty of Lutatius (241 BC) that had ended the First Punic War—and supposedly all future Roman-Carthaginian conflicts—Versailles had tragically combined the worst possible aspects of a peace settlement. The 440 articles within the treaty are often still interpreted as vindictive and thus cited as culpable for the rise of Hitler that followed. But the problem was far more complicated than that. Versailles was psychologically humiliating in its attribution of guilt for the war solely to Germany while, in fact, it was hardly punitive at all—at least in the sense of permanently and realistically preventing German rearmament. In contrast, after World War II the Allies’ postwar NATO agenda was roughly summed up by its first secretary general, General Hastings Ismay, as “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Had the victors of 1918, the so-called Big Four of Britain, France, Italy, and the United States, followed something analogous to the later NATO accord, Hitler might well have not come to power, a divided Germany would not have rearmed to the degree that it did under him, and the nascent Soviet Union would have been kept out of European power politics.

Such an effective paradigm was impossible, given that the Versailles Treaty of 1919 did not follow anything like the unconditional surrender of 1945. By November 1918, the German people had not suffered war on their own soil. Germany was tired and hungry, but it was not ruined. It was shamed by the victors for starting (and losing) the war but it had not been prevented from soon starting another one like it. No Allied power was unilaterally willing to monitor all the treaty’s provisions and to insist that Germany abide by the treaty’s arms-limitations accords. In a paradoxical way, precisely because Germany was not ruined by World War I, the Allied powers were subsequently hesitant to occupy it, rightly suspicious of the likelihood of German pushback.34

Worse still, Germany emerged after 1918 in better geostrategic shape than either of its traditional rivals, France or Russia. The latter by 1919 was torn apart by revolution, had large parts of its territory fought over, occupied, and liberated, and was now separated from European affairs by the creation of a number of Eastern European buffer states. France, with well over twenty million fewer citizens than Germany, could much less than Germany afford the losses of World War I and it had suffered catastrophic damage from the four-year occupation of swaths of its territory by the Kaiser’s army. And with the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian Empires, Germany was much more easily able to fill the vacuum of power in the East.35

The Versailles summit began in January 1919, months after the cessation of hostilities. Perhaps 75 percent of the victorious Allied ground forces were already demobilized. They were not easily called back to enforce terms placed on an already resentful Germany. Germans cited the global dangers of a spreading Bolshevism, and warned the arbiters at Versailles that any punitive occupation would only lead to Russian-style communism all the way to the Rhine. Ostensibly there were real indemnities (when and if enforced), but they came without commensurate Allied efforts to guarantee either German impotence or its permanent transition to a more viable democratic system. The departure from the battlefields quickly after the armistice may have instilled among the victors a sense of discord, weakness, and shame, while empowering those among the defeated who thought that the winners were neither confident nor strong. It was not the unwillingness of the United States to join the League of Nations that helped doom the former Allies, but America’s refusal to remain well-armed and ready to conduct a mutual defense treaty with France and Britain that likely encouraged Hitler.36

In sum, by the standards of the era, Versailles was mild. The treaty was not as harsh as the peace Germany had imposed on France in 1871. It was softer than the terms Germany forced on the nascent and defeated Soviet Union in February 1918. The surrender package that German diplomat Kurt Riezler’s plan had envisioned for France in the heyday of late summer 1914, the so-called Septemberprogramm, was far more punitive than Versailles. Humiliating but not emasculating a defeated enemy is far riskier than showing magnanimity to a beaten adversary that is then occupied, politically reformed, and stripped of its ability to renew war.

Germans could accept culpability if they were soundly beaten and shamed—that was clear after 1945—but not if their homeland was allowed to remain sacrosanct, as it was in 1918. Soon almost all German politicians monotonously blamed their subsequent economic miseries on reparations, or on the Danzig Corridor, or on the War Guilt Clause of the treaty, rather than on their own inept economic policies or social instability. They listened to Hitler when he reminded them that the Fatherland had remained largely untouched during and after the war. While there had been far fewer riots and less unrest back home than Hitler later alleged, the collapse of the magnificent army was blamed on backstabbers—Jews or communists who did to the German Army what the Americans, British, and French could not. The angst was not that Germany had started the war by invading neutral Belgium, but only that it had somehow lost the war while still occupying foreign territory, east and west.37

Hitler’s generals later conceded that the Allies, even by 1939–1940, had been better armed than Germany, but lost their initial border wars due to poorer morale. Defeatism had infected the French aristocracy, and some of the French Right saw Hitler as a preferable alternative to the French Left (“Better Hitler Than Blum” was a slogan expressed against French Socialist Léon Blum). Or as Field Marshal Erich von Manstein explained the conquest of Western Europe in 1940, “indeed, as far as the number of formations, tanks and guns went, the Western Powers had been equal, and in some respects even superior, to the Germans. It was not the weight of armaments that had decided the campaign in the West but the higher quality of the troops and better leadership on the German side. While not forgetting the immutable laws of warfare, the Wehrmacht had simply learnt a thing or two since 1918.” Or perhaps not entirely. In World War I, Imperial Germany had waged a traditional war that was ended by armistice without occupation of the Fatherland. Hitler’s second attempt at remaking the map of Europe was a war of annihilation that would end in the destruction of Germany itself. Berlin in May 1945 did not look at all like it had in November 1918.38

IN SUM, GERMAN humiliation and shame, and French, British, Russian, and American laxity, along with other shadows of World War I all explain why a war broke out twenty years after Versailles. But the vast differences between 1914 and 1939 also account for why it progressed so differently. The next time around the greatest disconnect would prove to be found in civilian casualties. The majority of the seventeen million who perished in World War I were combatants (59 percent), and there were roughly even losses among the Allied and Central powers. More telling, World War I noncombatant deaths were largely a result of either war-related famine or disease—most commonly the horrific Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 and the often inept efforts to combat it—or from blockades and agricultural disruptions.

World War II was largely a deliberate effort to kill civilians, mostly on the part of the Axis powers. Most of the fatalities were not soldiers: perhaps 70–80 percent of the commonly cited sixty million who died were civilians. Noncombatants perished mostly due to five causes: (1) the Nazi-orchestrated Holocaust and related organized killing of civilians and prisoners in Eastern occupied territories and the Soviet Union, as well as Japanese barbarity in China; (2) the widespread use of air power (especially incendiary bombing) to attack cities and industries; (3) the famines that ensued from brutal occupations, mostly by the Axis powers; (4) the vast migrations and transfers of populations, mostly in Prussia, Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and Manchuria; and (5) the idea prevalent in both totalitarian and democratic governments that the people of enemy nations were synonymous with their military and thus were fair game through collective punishments.39

The first war had remained a conflict of European familial nations that shared roughly the same assumptions about limited parliamentary government and the rule of the aristocracy. That was true of both the more authoritarian leaders of Germany and more socialist French and British democratic politicians. The actual or symbolic supreme commanders of three of the most powerful belligerents—King George V of Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia—were all related (the British monarch was first cousin to both the Kaiser and the Tsar) and indeed were almost identical in appearance and dress. With the exception of the Ottomans, all major powers had prayed to the same god. All claimed the same shared European past. Only within those common parameters would individual national character, ethnic pride, glorious history—call them what you will—galvanize one side or the other to greater effort.

That traditional European commonality had long imploded by the eve of World War II. National Socialism was to be a force multiplier of Prussian militarism. Italian fascism boasted it alone could restore the old Roman Empire. In Asia, the samurai code of Bushido gave credibility to warlords in Tokyo who had destroyed Japan’s incipient parliamentary government and promised a new Asian order under a Japanese-led Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Imperial Russia of the tsars was to be reinvented as the Soviet Union, trumpeting a new man and a new national secular religion based on state coercion and moral relativism—and especially the Red Army and American-style methods of mass industrial production. Mass popular movements in Germany, Japan, Italy, and Russia defined themselves in antitheses to monarchy and bourgeoisie republican government. National armies became ideological and revolutionary armed forces. Prussian militarism by 1918 had arguably proved to be more savage than that of any of the Allies. But German mercilessness was nonchalantly accepted as a given by late autumn 1939. The Wehrmacht was not just formed from German-speakers residing on ancestral soil but was now reinvented as a mythological pure Volk that deserved superior status, in the way that the razza best captured Mussolini’s new Italy and Yamato-damashii entailed more than just those who spoke Japanese or lived under Japanese auspices. Weaker indigenous peoples in Africa, Asia, and the Americas would fall because, in Darwinian terms, they deserved to be enslaved. Western Europeans likewise would concede, not because they were necessarily inherently inferior, but because they had become decadent in their leisure and wealth, without a national ethos or muscular religion—or dynamic leader.

When warned by his generals in August 1938 that the so-called Westwall (known in English as the Siegfried Line and later the site of the bloodbath in the Hürtgen Forest), a defensive fortification built between 1938 and 1940 opposite to the Maginot Line, would not prevent attacks from France and its allies if Germany attacked Czechoslovakia, Hitler scoffed: “General [Wilhelm] Adam said the Westwall would only hold for three days. I tell you, it will hold for three years if it’s occupied by German soldiers.” When pondering whether Italy should join the war on the side of Germany in April 1940, Mussolini pontificated, “it is humiliating to remain with our hands folded while others write history. It matters little who wins. To make a people great it is necessary to send them to battle even if you have to kick them in the ass.”40

Given these realities, Churchill and Roosevelt insisted that the totalitarian and nationalist ideologies that drove the Axis to war in a way unlike past bellicosity must be destroyed. Sober Germans, Italians, and Japanese, in the Allied way of thinking, had to be freed from their own hypnotic adherence to evil, even if by suffering along with their soldiers. Armistices this time around would not do. Nor would a second round of the Versailles Treaty. The Allied victory must be unconditional. Death was commonplace in World War II because fascist zealotry and the overwhelming force required to extinguish it would logically lead to Allied self-justifications of violence and collective punishment of civilians unthinkable in World War I. The firebombing of the major German and Japanese cities, the dropping of two atomic bombs, the Allied-sanctioned ethnic cleansing of millions of German-speaking civilians from Eastern Europe, the absolute end of the idea of Prussia—all by 1945 had earned hardly a shred of remorse from the victors.

Despite German brutality in 1914, there had been nothing quite similar to the Waffen SS (the military arm of the Schutzstaffel or “protective squadron”) and nothing at all akin to Dachau or the various camps at Auschwitz. The Kaiser’s Germany would not have exterminated seventy to ninety thousand of its own disabled, chronically ill, and developmentally delayed citizens, as the Third Reich had by August 1941. The idea of Japanese kamikazes might have been as foreign in 1918 as it was largely unquestioned in late 1944. In 1918, Imperial Germany at least surrendered without the occupation of its homeland—a scenario impossible to envision in 1944–1945. Some eleven thousand American and Filipino troops gave up Corregidor to avoid starvation and needless losses in May 1942. In contrast, the subsequent 6,700 Japanese occupiers did not similarly quit the island fortress in February 1945, but had to be killed nearly to the last man. The destruction of populist ideologies, especially those fueled by claims of racial superiority, proved a task far more arduous than the defeat of a sovereign people’s military.41

There were still other catalysts that would explain the second war’s singular loss of life. The technology of mass death was more developed than it had been in 1918. True, the mass use of poison gas, submarines, warships, artillery, machine guns, repeating rifles, grenades, and mines all predated 1939. The ground soldier at the war’s beginning in 1939 was superficially similar to his 1918 counterpart. Both often carried bolt-action rifles and grenades. They likewise fell prey in droves to artillery shelling and machine guns. Steel helmets continued to offer inadequate head protection. There was still no practical and universally worn body armor that could deflect rifle bullets. In history’s endless cycle of challenge and response, the shift toward the offensive brought about by industrial weaponry still remained in control. Infantry still had not many choices other than foxholes and trenches to survive artillery barrages. Field guns were larger, more numerous, and more accurate, yet they appeared to the eye similar to the artillery of World War I. At sea, the guns of battleships were more accurate but not always that much larger. Destroyers and cruisers were faster and often greater in size, but nonetheless were still recognizable as destroyers and cruisers. Most World War II surface ships were superficially indistinguishable from their World War I counterparts—many would see service in both wars—even if their armament, engines, and artillery were superior. Submarines, torpedoes, and depth charges were improved over those of World War I, but they were not new.

More important, the ability to move men and materiel and to travel far more easily by land, air, and sea proved a catalyst for turning a European border dispute into a global war. Compared to what had seemed the ultimate in lethal weaponry in World War I, these scientific and industrial revolutions ensured tens of millions of more deaths in the second war. And the majority of the innovations favored the Allies, who nonetheless would lose far more lives than the Axis. The first breakthrough was in air power. By 1939, the evolution of fighters and fighter-bombers helped to make trench warfare rarer, while augmenting the ability to clear the advance and protect the flanks of fast-moving motorized columns. Tactical air support of ground troops vastly increased their lethality. Strategic bombing brought the war home to civilian populations, raising questions about the level of civilian culpability for the war effort unknown in past conflicts. By war’s end, the destruction wrought by Allied tactical and strategic aircraft, mostly American and British, simply dwarfed any similar air efforts achieved by the Axis powers. The belated success of bombers from mid-1943 through 1944 and onward wrecked the German petrochemical and transportation industries and diverted huge numbers of planes and artillery from the Eastern Front to the homeland.42

Armored and transport vehicles in no way resembled the erratic, clunky machines that had achieved temporary tactical advantages between 1916 and 1918. Just two decades later, sophisticated vehicles appeared in the tens of thousands, and were increasingly mechanically reliable and far more powerful, as well as far better armed and protected. A Jeep or tank in 1945 looked more like its counterpart in 2016 than in 1918. Shock-and-awe tactics allowed independent groups of Panzers to spearhead infantry advances and achieve breakthroughs otherwise impossible in the past. Rapid envelopments, particularly on the Eastern Front, would result in vast captures of prisoners on a scale unknown in World War I.

One lesson of the conflict was that speed kills. When soldiers could cover more distance and at greater speeds, they inflicted more death. Entire divisions could now move over thirty miles a day and be supplied from hundreds of miles to the rear. The access to refined fuels was critical to all logistics and governed strategies about long-term supply. At the end of World War I, the British foreign secretary, Lord Curzon, had summed up the victory with the quip, “we swam to victory on a sea of oil.” The same would prove true of the Allies in World War II.43

Over four million military trucks were produced in World War II. Despite the greater numbers of combatants, there were probably fewer horses employed in World War II than in World War I, and after 1940 most were confined to the German and Soviet armies. The latter had largely evolved to motorized transport by late 1944 (near the end of the war, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels called the Soviet army “motorized robot people”), in part due to the gift of 457,561 American trucks and armored vehicles. By contrast, until the end of the war the fuel-short Wehrmacht still depended on the horse for the majority of its infantry’s transportation needs. Journalists by 1941 had mythologized blitzkrieg. But more often Germans conducted a Pferdkrieg, a war relying on horses—and plentiful spring and summer pasturage.44

Aircraft carriers proved critical naval assets at the very beginning of the Pacific war. They rapidly ensured the obsolescence of the battleship, which was to all but disappear as a decisive asset by the end of the war. The vast majority of ship losses in World War II were to torpedoes or bombs launched from submarines, planes, and destroyers. In comparison, few ships sank due to the thundering broadsides of behemoth battleships or heavy cruisers. Naval and occasionally land-based air power turned the great sea battles—the fighting near Singapore, the chase of the Bismarck, the Coral Sea, Midway, the fight over the Marianas, Leyte Gulf, and Okinawa—mostly into contests of carrier-based aircraft attacking with impunity any enemy ships except like kind. During the entire war, only two light carriers and one fleet carrier (HMS Glorious) were destroyed by surface ships. The vast imbalance between Axis and Allied total carrier production (16 to 155) meant that tactical air superiority over the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Pacific was far easier for the Allies to achieve than for their enemies. Neither the Russians, the Germans, nor the Italians deployed aircraft carriers. Their respective modest surface fleets were hampered by ineffective air cover. That absence hurt the Kriegsmarine far more than it did the Soviet military. The Soviet Union remained primarily an infantry power with a land-based air force, without obligations abroad—but with two allies in the European theater with large carrier forces. Axis carriers and naval air pilots were exclusively Japanese. But by war’s end they were dwarfed by the huge production totals of the Anglo-Americans. Apparently, Germany had always believed that its future wars would be confined to the continent and thus naval air power would be less important, and that the seas of the Baltic and Atlantic were not conducive for air operations. Admiral Raeder in lunatic fashion early on summed up the German appraisal of carriers as “only gasoline tankers.”45

Even if its Kriegsmarine had come to its senses and reordered its priorities, Germany had too few resources to build a respectable carrier fleet. Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union had ensured a great need for Axis ground troops, trucks, and armor. Back home over the skies of Germany, Luftwaffe fighter aircraft soon became critical to intercept the growing number of Allied bombers. Given those obligations in the air and on the ground, German and Italian carriers again remained a fantasy. Meanwhile, Axis surface ships were never replaced in the ratios they were lost, often to Allied naval air power. After 1943, the British and Americans alone kept building larger surface ships, frequently used to support amphibious operations.

Breakthroughs in electronics, medicine, and high technology also favored the Allies. Britain and the United States did not so much display preponderant inventive genius as a pragmatic sense of how to deploy new scientific inventions on the battlefield more quickly and in the greatest quantity. Radar and sonar ended the idea of stealthy invulnerability in the clouds or in the ocean depths. By 1940, the trajectories of planes and submarines could be identified in advance of visual sighting. War was unleashed from at least some of its traditional weather-related restraints.

The British and Americans outpaced the Germans in all these critical technologies that made war far deadlier. Or, when the Allies fell behind in development, they quickly caught up and rendered initial Axis breakthroughs irrelevant. The introduction of plasma, sulfa drugs, mass vaccinations, and belatedly, penicillin, meant that septicemia, tetanus, gangrene, and other bacterial infections were not always fatal. The old category of “wounded” was no longer necessarily a step on the way to “killed in action.” In all areas of medicine, the British and American armies proved the most efficient in treating soldiers’ combat injuries and preventing disease, although the Germans were more effective (or brutal) in returning wounded soldiers to combat.

Jet engines and rocketry would eventually revolutionize warfare. Both were on the horizon but neither arrived in time nor in enough numbers to change the course of World War II. In the case of much faster Luftwaffe jets, huge numbers of superb piston-driven Allied fighters, especially British Spitfires and American Mustangs, overwhelmed fuel-short and often poorly piloted Messerschmitt Me 262 Swallows. That the Axis produced rockets, jets, and superior torpedoes, and yet were the most reliant on horse transportation, is emblematic of their lack of comprehensive industrial policy and pragmatic technological planning—an area where America, Britain, and the Soviet Union excelled. We often forget that the Third Reich was postmodern in creative genius but premodern in actual implementation and operations.

Two final unforeseen inventions, the atomic bomb and the ballistic missile, were used only at the end of the fighting to eerie, if controversial, effect. In contrast to Germany’s squandered scientific breakthroughs, the atomic bombs were primarily responsible for the avoidance of an invasion of Japan. If the body counts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were less than those who perished from the conventional firebombing of the other Japanese cities, and if V-2 missiles killed far fewer British than plodding Flying Fortresses and Lancasters did Germans, the new weapons’ aggregate potential for mass death on the immediate horizon was also far greater. Had the war gone on for a few more years, it was possible that huge fleets of missiles, and perhaps even atomic-tipped projectiles (albeit only by the United States), would have become feasible and freely used.46

Finally, all of the belligerents would subordinate military decision-making to civilian leaders. There were to be no Alexanders, Caesars, Napoleons, or even de facto supreme military leaders such as Generals Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg, who by the last year of World War I were making most of Imperial Germany’s military and strategic determinations, unfettered by much civilian oversight. Both decided to quit the war in panic when they saw their armies losing. Likewise, in the latter months of World War I, Generals Douglas Haig, Ferdinand Foch, and John J. Pershing, without much audit, crafted most of the Allied strategic decisions on the Western Front. In contrast, in World War II all of the war’s greatest battlefield luminaires—General George Marshall, General Georgy Zhukov, General Bernard Montgomery, General Dwight Eisenhower, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, and German generals Franz Halder, Erich von Manstein, and Erwin Rommel––followed strategic initiatives set out by Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin, and Hitler, as well as Tojo (though himself an active army officer) with guidance from Emperor Hirohito. It may sound counterintuitive, but generals are usually more sparing with their troops than are their civilian overseers.

Hitler and Stalin in 1941 and 1942 adopted militarily unsound strategies that added to the horrific body counts of World War II. Unnecessary entrapment of Soviet armies had led to over four million Russian dead by the end of 1941. Nearly as disastrous were the no-retreat German sacrifices such as that at Stalingrad at the end of 1942 and those throughout much of 1943–1945. World War II partly disproved Georges Clemenceau’s famously paraphrased line, “war is too important to be left to the generals.” In fact, a global war was too important to be left in the hands of a civilian ex-corporal.

In sum, World War II was in some sense a traditional conflict that was fought over familiar military geography of the ages. It was sparked by age-old human passions such as fear, honor, and self-interest, and more specifically by the loss of classical deterrence that can be predicated on impressions and appearances almost as much as hard military power and resources. However, its twentieth-century incarnations of totalitarianism, whether German Nazism, Italian fascism, Soviet communism, or Japanese militarism, often made the aggressors erratic rather than circumspect and predictable. All the warring parties assumed that the end of the war would not be achieved through armistices and concessions but through the existential destruction of their enemies. Such resolution accepted not just that the Axis powers were skilled killers, but also that Germany and Japan in particular would likely concede defeat only when ruined, thus requiring their Allied opponents to embrace commensurate levels of violence. Totalitarianism, when married to twentieth-century industrial technology, logically led to general destruction on a global scale.

If it is mostly clear why the war was fought and how it became so lethal, why then were the alliances so unstable, the belligerent partnerships often so unalike, and their respective visions of victory so different?