6

New Terrors from Above

THE MOST DEADLY weapon of the entire war was the huge American B-29 bomber. It turned on its head the bankrupt idea of gigantism, as seen in the examples of the battleship Yamato or German so-called Royal or King Tiger tanks. In the B-29’s case, perhaps uniquely of all new World War II weaponry, vastly bigger indeed proved vastly better. The B-29 squared the circle of gigantism by being both huge and numerous—the only gargantuan weapons system of its class that was nonetheless built in plentiful numbers (about 4,000). The Boeing Superfortress is forever remembered as conducting the lethal napalm raids over Japan and as the first and only plane in history to drop atomic bombs during wartime. From the beginning of the war, the Americans had accepted that it would be far harder to bomb island Japan than mainland Germany and Italy with their existing land-based multi-engine bombers. The Japanese home islands were surrounded by concentric archipelagoes, all fortified and defended by hundreds of thousands of veteran Japanese troops and fighter hubs. Friendly air bases in China and India were distant and not easily supplied. The weather in the Far East was unpredictable and its patterns less well studied than in Europe.

Japanese industry was largely still untouched by serious raids until early 1945. Even as Japan was losing the war—suffering unsustainable fighter losses and lacking adequate fuel stocks even for pilot training—its industries by mid-1944 were still producing more combat aircraft than at any time during the war. In late February 1945, Tokyo was still virtually unharmed, even as Berlin was in veritable ruins.

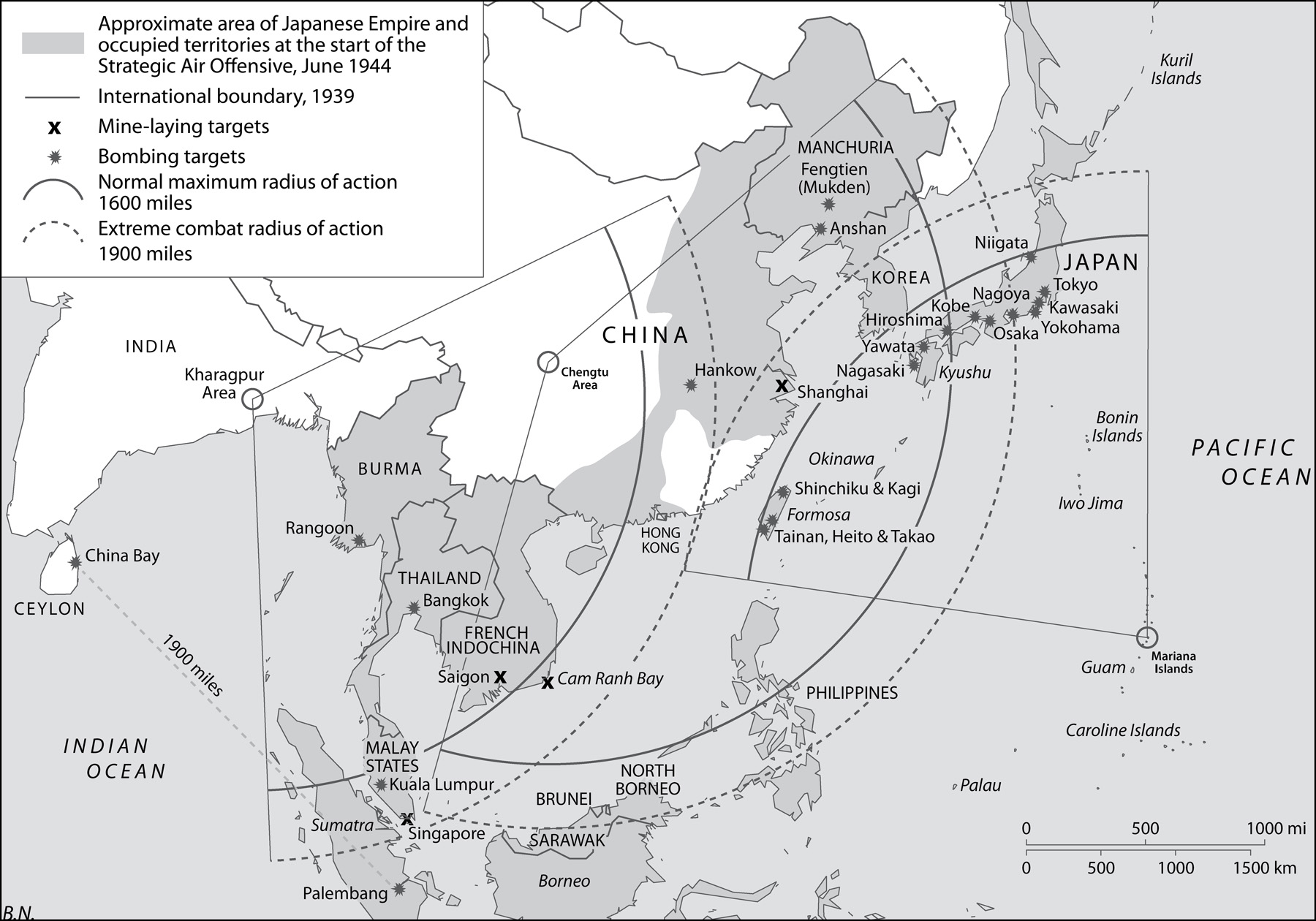

For the Americans, the only effective way to ruin Japan’s production was to deploy an innovative, ultra-long-range heavy bomber from great distances, stationed on any island within a radius of roughly 1,500 miles from the Japanese homeland. The round-trip ranges of existing Allied heavy bombers—B-17s, B-24s, and Lancasters—were adequate to reach most of the Third Reich from various bases in Britain and Italy, but in the Pacific they lacked an additional thousand miles for round-trip missions from any conceivable island base.1

The solution, contemplated even before the beginning of the war, was not cheap. The B-29 Superfortress program probably cost more than the Manhattan Project to build the atomic bomb: somewhere between $1 billion and $3 billion, depending on how various associated research and development costs were allotted. The most sophisticated plane in aviation history to that point entered mass production less than two years after the flight of the first prototype on September 21, 1942. The bomber was enormous. Its 141-foot wingspan (well over twice that of most German bombers) and over 130,000-pound maximum loaded weight dwarfed its large B-17 Flying Fortress predecessor (103-foot wingspan, 54,000-pound loaded weight). With a crew of eleven, just one more than on most models of the B-17, the Superfortress was faster (top speed 365 mph), normally carried almost twice the payload (10 tons), and vastly extended the nature of round-trip operations (in theory between 3,200 and 5,800 miles).2

Use of the revolutionary but temperamental plane hinged on massive support and logistics. It guzzled so much fuel—between four and five hundred gallons of gasoline per hour—that logisticians eventually grasped that B-29 fleets in war zones could only be supplied by sea. The bomber’s four Wright R-3350–23 Duplex-Cyclone turbosupercharged—but problematic—radial engines, the new innovative computerized and synchronized gun systems, and a novel pressurized cabin all required constant maintenance, expensive spare parts, and skilled ground crews. In the words of General Curtis LeMay, who by January 1945 was in command of all American strategic bombing operations against the Japanese homeland, the novel B-29 “has as many bugs as the entomological department of the Smithsonian Institution. Fast as they got the bugs licked, new ones crawled out from under the cowling.” The nose segment alone, for example, required over a million rivets and some eight thousand parts. Some 1,400 subcontractors supplied parts for the plane.3

Although the American public expected missions against the Japanese home islands as quickly as possible, the initial B-29 bases in India and China were not so easily accessed, much less supplied, and at times were vulnerable to Japanese counterattacks. By the end of the war, B-29 losses had totaled well over four hundred of the monster planes, the majority of them probably from accidents and mechanical failure—a statistic not necessarily indicative of unreliable planes per se, as much as the novel doctrine of taking off from distant islands in new aircraft, flying mostly over water, often at night, and encountering rough weather over Japan, with a continuous flight time of sixteen hours and longer.

Strategic Bombing in the Pacific

Indeed, the long 1,500-mile flight from the Mariana bases—ready for frequent missions by November 1944—to the Japanese mainland often resulted in navigation errors and lost planes. And while the loss rate per individual sortie was “tolerable” (approximately 1.4 planes lost per 16-hour mission), given the thirty-five-mission service requirement (later often increased) and long distances over sea in darkness, it was likely that a third of the crews would not survive. Altogether, over three thousand B-29 crewmen were killed or went missing.4

The plane’s ability to fly above thirty thousand feet when heavily loaded, at theoretical operational speeds of nearly three hundred miles per hour, was supposed to make the B-29 almost invulnerable to flak and enemy aircraft as it methodically blew apart Japanese industry with precision bombing. Although the huge bomber was never used against Germany, news reports of the B-29’s performance characteristics terrified Hitler himself, being the concrete manifestation of his pipe dreams of “Amerika” and “Ural” bombers. And when four B-29s came into Stalin’s hands, he immediately ordered them reengineered as the Tupolev Tu-4, the Soviet Union’s first successful, long-range heavy bomber. Between 1947 and 1952, over eight hundred Tu-4s were built and then later deployed as nuclear bombers well into the 1960s.5

The gargantuan bomber entered service in May and June 1944, just months after the black weeks of nearly unsustainable losses of B-24s and B-17s in Europe. As a result, there were growing worries that the European experience of four-engine heavy bomber vulnerability might prove catastrophic to the B-29 program, given that each plane initially cost between two and three times more than the complex B-24 Liberator—and much more when all the research costs of the innovative plane were prorated.

High winds were a near constant over usually cloudy China, occupied Southeast Asia, and Japan. The India- and China-based B-29s were neither able to fly with regularity nor bomb with accuracy, in part due to inexperienced crews. Only about 5 percent of their aggregate bomb loads ever hit the intended targets. Almost no accurate intelligence existed about the exact location of particular Japanese munitions industries. Prior to the March 9–10, 1945, incendiary raids, only 1,300 Japanese had died as a result of US bombing of the Japanese homeland. The B-29 project was on the verge of being the most expensive flop in military history, making Hitler’s catastrophic investment in the V-2 guided ballistic rocket look minor by comparison.6

The eventual solution settled on by General Curtis LeMay—who previously had flown extensively as a B-17 group and division commander in Europe, and formally took over from General Haywood S. Hansell the B-29 XXI Bomber Command based on the Mariana Islands in January 1945—was contrary to the entire rationale of the huge plane’s design and proved as brilliantly counterintuitive as it was brutal, simplistic—and controversial. Rather than flying high and relatively safely in daylight as intended, LeMay’s B-29s would now go in low at between five and nine thousand feet. The squadrons, in British fashion, would bomb mostly at night, and, at least during the first three incendiary missions, without their standard full defenses or reliance on precision bombsights. Staying at low altitude spared the temperamental engines, saved fuel by obviating climbing to required higher altitudes, and upped the payload of bombs to ten tons and more, an incredible load for prop-driven bombers. Mixed loads of new M-69 napalm incendiaries, combined with explosive ordnance, meant that the notorious Japanese jet stream was now an ally, not an impediment, to the B-29s’ destructiveness, spreading the inferno rather than blowing conventional bombs off target.

Payload, not accuracy per se, played to the strengths of the B-29. Japanese anti-aircraft defenses were short of rapid-firing, smaller-caliber guns and thus were mostly unable to deal with nocturnal low-flying bombers arriving at fast speeds. In addition, the American capture of Iwo Jima was ongoing, and by the time of the March fire-raids the Americans were near to mopping up the island. Its capture would at last allow a more direct (and fuel-saving) B-29 route to Tokyo without the worry of hostile fighter attacks on the way.7

None of LeMay’s superiors would later object to such a radical change of tactics on either moral or operational grounds. In part, their silence reflected the reality that, even before Pearl Harbor, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had ordered research into firebombing Japanese cities as part of contingency plans to wage war against Imperial Japan, given that nearly four in ten Japanese lived in cities. In part, it was a mark of respect for LeMay, who had led some of the most dangerous missions on B-17s over Europe and flew early and hazardous B-29 sorties over the Himalayas from China. In addition, there was recognition that traditional high-altitude missions were ineffective, or as LeMay characterized his role, “you go ahead and get results with the B-29s. If you don’t get results, you’ll be fired. If you don’t get results, there’ll never be any Strategic Air Forces of the Pacific.”8

As in the case of the other architect of Allied incendiary bombing, British Air Marshal Arthur Harris, LeMay would face caricature and censure in the postwar era, at least some of it originating from the firebombing of Japan. Torching civilian centers was contrary to the entire moral pretenses of the US precision strategic bombing thus far in the war. And LeMay’s predecessor, General Haywood Hansell, had argued that his precision strikes were improving and had at least forced the Japanese to disperse industry, thus impairing productive efficiency.

Unlike “Bomber” Harris, LeMay wisely made few extravagant claims, at least at first, about “dehousing” the Japanese population and ending the war outright, but rather insisted that incendiaries were unfortunately necessary to compensate for the fact that dispersed factories were embedded among the civilian population. When Japanese production dropped, LeMay logically took credit and defended the high civilian death tolls. He enjoyed the role of a take-no-prisoners general, but beneath his crusty exterior, like George S. Patton, he was one of the most introspective, analytical, and naturally brilliant commanders of the war. If he was a frightening man in his single-minded drive “to put bombs on the target,” he was also an authentic American genius at war.9

The March 9–10, 1945, napalm firebombing of Tokyo remains the most destructive single twenty-four-hour period in military history, an event made even more eerie because even the architects of the raid were initially not sure whether the new B-29 tactics would have much effect on a previously resistant Tokyo. The postwar United States Strategic Bombing Survey—a huge project consisting of more than three hundred volumes compiled by a thousand military and civilian analysts—summed up the lethality of the raid in clinical terms: “Probably more persons lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a 6-hour period than at any time in the history of man.” Over one hundred thousand civilians likely died (far more than the number who perished in Hamburg and Dresden combined). Perhaps an equal number were wounded or missing. Sixteen square miles of the city were reduced to ashes. My father, who flew on that mission, recalled that the smell of burning human flesh and wood was detectable by his departing bombing crew. A half century later, he still related that the fireball was visible for nearly fifty miles at ten thousand feet and shuddered at what his squadron had unleashed.

After the horrendous raid, there was no way to stop the new B-29 deliveries of mass death, except for shortages of napalm at the Marianas depots. In the next five months, LeMay destroyed more than half the urban centers of the largest sixty-six Japanese cities, as he used the B-29 in exactly the opposite fashion for which it was designed. Japanese on the ground believed that it was the firebombing of the medium- and smaller-sized cities that finally broke civilian morale, given that the damage was increasingly widely distributed. As one firsthand observer put it: “It was bad enough in so large a city as Tokyo, but much worse in the smaller cities, where most of the city would be wiped out. Through May and June [1945] the spirit of the people was crushed.”10

American B-29s probably caused well over a half-million civilian deaths in toto, although the exact number can never be accurately ascertained. Certainly, the bombing helped to ensure that the production of both Japanese weapons and fuels came to a near standstill. Crews might fly up to 120 hours per month, far more than normally scheduled B-17 missions in Europe. On days when the B-29s did not firebomb, they hit key Japanese harbors, dropped mines, and soon reduced shipping by over half. The bombers may have damaged Japanese industry as much by shutting down its transportation, ports, docks, and factory supplies as by the firebombing of industrial plants. Over 650,000 tons of Japanese merchant shipping was destroyed and another 1.5 million tons rendered useless, given the inaccessibility of ports and Allied control of the air and sea.11

Area and incendiary bombing over Europe had finally turned controversial, yet after February 1945 there was hardly any commensurate moral concern about burning down Japan. A variety of reasons explained the paradox, apart from the oft-cited racial animus against Japan that had surprise-attacked the United States and the growing fatigue from the continuation of the war after the surrender of Germany. The weather and jet stream made precision bombing far more difficult over Japan, while the nature of Japanese wooden and paper construction ensured that firebombing would be unusually effective. The Great Kanto earthquake and fire of 1923 had consumed the wooden buildings of Tokyo and Yokohama and killed 140,000—a fact not lost on American air war planners.12

Whereas the British had embraced area bombing in Europe early on in the war, and the Americans had clung stubbornly to the idea of more precision attacks, in the Pacific the moral calculus now worked quite differently. The Americans alone conducted the entire strategic campaign. They were no longer in the convenient position of being able to both criticize and learn from the efforts of an ally. The astronomical investments in the B-29 and its continued inability to serve as a precision bomber over Japan argued for immediate results at any costs, even if that meant nullifying some of the bomber’s original reason to be: its high-altitude invulnerability to flak and fighters and its accurate bombing of heavy industry. Finally, the bloody Iwo Jima (February 19–March 26, 1945) and Okinawa (April 1–June 22, 1945) campaigns had convinced American strategists that only air power could avoid an even deadlier ground invasion of the Japanese mainland. The net result was a near unanimous though often unspoken willingness to burn up the cities of Japan.

As for the morality of the fire raids, the Americans argued that they could not be entirely blamed, given that before impending incendiary attacks began they dropped generic leaflets warning civilians to vacate: for example, “Unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” But how exactly evacuating Japanese families were to survive in the countryside during March and April was another story, as was knowing exactly when a Japanese city on the list was actually to be targeted. It was also doubtful that entire populations would have been able to obtain permission to leave from the Japanese military.

LeMay and his generals also cited the dispersed nature of the Japanese industrial war effort, which deliberately sought to integrate war production with civilian centers, and thus paradoxically ensured that the fire raids hit both civilian and military-industrial targets. They also pointed out that, while the final outcome of the war was not in doubt, nevertheless, thousands of American, British Commonwealth, and Asian soldiers were dying each day, fighting the Japanese and suffering from disease and maltreatment in Japanese prison camps. Later, Japanese accusations of genocide by air rang hollow to the Americans, given that the Imperial Japanese Army was responsible for perhaps fifteen million dead in China alone, a theater that the Allies had no real ability to enter with force before 1945. Nonetheless, the blunt-spoken LeMay confessed, “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal.”13

Firebombing probably shortened the Pacific war by nearly destroying Japanese industry and commerce. B-29s may have eroded civilian morale in a way not true of the European bombing, although after the terrible Tokyo raid, firefighting and civil defense improved and Japanese civilian losses went down in other cities under attack. Still, a Japanese reporter, pressed to deny American boasts of damage to Japanese cities from the fire raids, instead conceded, “Superfortress reports of damage were not exaggerated: if anything, they constitute the most shocking understatement in the history of aerial warfare.” By summer 1945, only four major cities—Kyoto, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Sapporo—remained largely undamaged.14

Both atomic bombs were dropped from B-29s, the only American bomber capable of carrying the ten-thousand-pound weapons and reaching the Japanese mainland from the Mariana bases. Most controversy over the use of the two bombs centers on the moral question of whether lives were saved by avoiding an invasion of the mainland. The recent Okinawa campaign cost the Americans about twelve thousand immediate dead ground, naval, and air troops, and many more of the fifty thousand wounded who later succumbed, with another two hundred thousand Japanese and Okinawans likely lost. But after the bloodbaths on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, those daunting casualties might well have seemed minor in comparison to the cost of an American invasion of the Japanese mainland.

The ethical issues were far more complex and frightening than even these tragic numbers suggest. With the conquest of Okinawa, LeMay now would have had sites for additional bases far closer to the mainland, at a time when thousands of B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers, along with B-25 and B-26 medium bombers, were idled and available after the end of the European war. Dozens of new B-29s were arriving monthly—nearly four thousand were to be built by war’s end. The British were eager to commit Lancaster heavy bombers of a so-called envisioned Tiger Force (which might even in scaled-down plans have encompassed 22 bomber squadrons of over 260 Lancasters). In sum, the Allies could have been able to muster in aggregate a frightening number of over five thousand multi-engine bombers to the air war against Japan. Such a force would have been able to launch daily raids from the Mariana Islands as well as even more frequently from additional and more proximate Okinawa bases against a Japan whose major cities were already more than 50 percent obliterated.

A critical consequence of dropping two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki may have been not just precluding a costly American invasion of Japan, but also ending a nightmarish incineration of Japanese civilization. Otherwise, by 1946 American and British Commonwealth medium and heavy bombers might have been able to mass in numbers of at least two to three thousand planes per raid. Just two or three such huge operations could have dropped more tons of TNT-equivalent explosives than the two atomic bombs. Within a month, such an Allied air force might easily have dropped destructive tonnage equivalent to ten atomic bombs, following the precedent of the 334-plane March 9–10 fire raid of Tokyo that killed more Japanese than either the Hiroshima or Nagasaki nightmares.

“It seemed to me,” Japanese prime minister Kantaro Suzuki remarked after the war, “unavoidable that, in the long run, Japan would be almost destroyed by air attack, so that, merely on the basis of the B-29s alone, I was convinced that Japan should sue for peace. On top of the B-29 raids came the atomic bomb, which was just one additional reason for giving in.… I myself, on the basis of the B-29 raids, felt that the cause was hopeless.” LeMay was not far off the mark when he said of the use of the atomic bombs, “I thought it was anticlimactic in that the verdict was already rendered.”

Without the decisive B-29 fire raids and the dropping of the atomic bombs, the American legacy of strategic bombing in the postwar era would have remained much more problematic, given the huge losses of bombers over Europe and the need for ground troops storming Germany. In contrast, the lethality of the B-29s led to a postwar consensus, rightly or wrongly, that huge manned bombers could win a war, in the manner of the fire raids, by destroying the enemy’s heartland without the need to invade the enemy homeland with infantry forces. That checkered tradition was highly influential in the Cold War, particularly in the Korean and Vietnam Wars, until the onset of laser- and GPS-guided precision weapons in the 1980s gave planners greater strategic—and apparently ethical—latitude.15

In unmistakable irony, it took the genius of LeMay to reinvent the B-29 into a low-level, crude fire-bomber (somewhat in the German tradition of the 1930s of envisioning two-engine medium bombers for low-altitude or dive-bombing missions), exploiting its singular advantages of range, load, and speed while ignoring its great strengths of high-altitude performance, pressurization, and sophisticated gunnery that had accounted for its huge research, development, and production costs. That the bomber was rushed into full production with largely untested technologies, and yet proved the most lethal conventional weapon of the war, was one of the great scientific marvels of the conflict.

IN SUMMER AND early autumn 1944, three radically new Axis aerial weapons made their appearance: the German V-1 and V-2 rockets, and the Japanese kamikaze suicide dive bombers. All reflected last-ditch efforts to nullify Allied air defenses through new technologies and strategies. They were admissions both that Allied aircraft dominated the skies and that there was no conventional remedy to redress that fact. Yet, apart from those shared assumptions, Hitler’s postmodern missiles and the Japanese premodern suicide planes could not have been more different.

The precursor to the V-2 rocket was the V-1 cruise missile (both were known as Vergeltungswaffen or “vengeance weapons” on the apparent logic that they were paybacks for Allied bombing, which itself was payback for initial German aerial aggression). The German propaganda ministry had persuaded the German public that at last the British would account for the firing of Hamburg and Cologne, which led to unrealistic expectations that the V-weapons might translate into fewer bombings of the homeland and a slowdown in the Allies’ progress on the ground. Instead, the initial hype about wonder weapons only ensured a general disappointment once it became clear to the Germans that the rockets had not led to any discernable letup in the British effort.16

The V-1 flying bomb was recognized by its peculiar engine noise as the “doodlebug” or “buzz bomb” to the British against whom it was predominately aimed. This early version of a cruise missile was little more than a self-propelled five-thousand-pound flying bomb with 1,900 pounds of actual explosive. A brilliantly designed and reliable pulse-jet engine ensured a subsonic speed of 350–400 mph, at relatively low altitudes of two to three thousand feet. The main drawback of the V-1 was not necessarily its relatively slow speed or payload or even range (not much over 150 miles), but its primitive autopilot guidance system, which was governed by a gyroscope, anemometer, and odometer that were only roughly calibrated by considerations of direction, distance, fuel allotment, winds, fuel consumption, and weight. At their peak almost a hundred V-1s were launched at Britain per day. When launched from across the Channel in occupied coastal Europe, most buzz bombs were intended to hit somewhere within the vast London megalopolis, but without much certainty where. In the end, the V-1s proved even more inaccurate than the bombs dropped during American “precision” daylight raids over Germany.

Exact figures on V-1 production and deployment remain murky and controversial. The Germans eventually may have built or partially assembled almost thirty thousand V-1s and actually launched over ten thousand of them at various targets in Britain, of which well over 2,400 struck London. After the Normandy invasion, almost another 2,500 were aimed at Allied-occupied Antwerp and other sites in coastal France and Belgium, where a far larger percentage made it through air defenses. Even though about half of all V-1s launched misfired, went off course, or were knocked down by Allied ground and air anti-aircraft efforts, over six thousand British civilians were killed by them, and nearly eighteen thousand were injured. But if the V-1 was less sophisticated and more vulnerable than the V-2 that followed, it also delivered a similar payload far more cheaply. The Germans could produce well over twenty V-1s for each V-2 built. Even though the slower V-1 was far more vulnerable to British defenses, there was still a better chance that the aggregate thirty-eight thousand pounds of explosive of a collective twenty V-1s might hit strategic targets than the 2,200 pounds of a single, albeit unstoppable, V-2. If just 25 percent of the V-1s arrived near a target, then the cost per payload ratio still bested a successful V-2 launch by a factor of five. But in the end, the productive capacity of the British munitions industry was completely unaffected by either of the two V-weapons.17

Despite the V-1’s short range, in terms of the cost of delivering a ton of explosives to a well-defended target, these early cruise missiles were not entirely ineffective for a side that was clearly losing the war. Unlike the terrible expense in crews and planes incurred in the 1940 failed German bombing of Britain, or the so-called Baby Blitz for four months in early 1944, the flights of the V-1s entailed few if any German military personnel losses, although thousands of starving slave laborers perished making the missiles. When weighed against the prior conventional need for fighter escorts and bomber crews, cruise missiles could be built and deployed relatively cheaply, and thus made the V-1 at least a formidable terror weapon.

True, the missiles did not harm British industry, but for months the buzz bombs diverted about a quarter of British bombing sorties to hunt down V-1 sites (reminiscent of Saddam Hussein’s 1991 use of inaccurate SCUD missiles against Israel that likewise, for a time, redirected critical air resources from US and coalition bombing missions). At war’s end, V-1s, despite their rather small aggregate tonnage, had achieved almost the same casualty rates and (admittedly unimpressive) structural damage on the enemy, per ton of explosive delivered, as did earlier German bombers, but without the human cost to the Luftwaffe.18

Some of the V-1’s terror arose from the timing of its appearance. The new weapon was deployed in force in June 1944, without warning, and more than three years after the end of the major air battles of the Blitz. (The 1944 Baby Blitz had killed around 1,500 British civilians and mostly ended in May.) The shocked British public had by then finally thought their homeland to be relatively safe from air attack, especially as Allied ground forces in Normandy would soon eliminate most German forward air bases in occupied Europe. Ultimately the V-1 threat against British cities ended only when sufficient European territory was occupied to render the short-range weapon ineffective, forcing the last generation of V-1s to divert to the port of Antwerp and its environs.19

The successor V-2 rocket was quite a different matter. A true ballistic missile, the V-2 proved to be a poor weapon in terms of the costs necessary to deliver explosives across the Channel. While many more of the cheaper V-1s were launched against British and European targets than the later V-2s (approximately 5,000–6,000 V-2s were built or partially assembled, and between 2,500 and 3,200 launched), there was absolutely no defense against the latter supersonic weapon. The rockets reached altitudes at their apex of fifty-five miles and hit the ground at speeds up to 1,800 miles per hour.

Only 517 V-2s were confirmed to have hit London proper. Nonetheless, they killed over 2,500 civilians and injured thousands more. On average, for every V-2 successfully launched against London, about five civilians were killed. Nonetheless, unlike the case of the V-1, Londoners soon accepted that there was no defense against the random hits of the supersonic V-2. The American playwright S. N. Behrman remarked of the V-2 effect on London in January 1945: “I had arrived late in the day, and the British government official who met me remarked casually that the first V-2s had fallen earlier. They had made deep craters, my host said, but had been far less destructive than had been anticipated. There were no instructions about how to behave if you were out walking when the V-2s came, he said, because there were no alerts. You just strolled along, daydreaming, till you were hit.”20

The comparison with traditional bombers was instructive. Just four or five large Allied bombing raids late in the war (500 planes carrying 4,000 pounds of ordnance each) delivered as much explosive as all of the V-2 launches combined. Yet both V-weapons proved evolutionary in a way that piston- and propeller-driven bombers did not. The V-weapons were respectively the antecedents of the late twentieth-century cruise missile and Cold War intercontinental ballistic rocket. Given the programs’ huge research and development budgets and their lack of precision targeting and relatively small payloads, what supported the use of at least the V-1 flying bomb (but not the far more expensive V-2 rocket) was its psychological effect upon the Allies in late 1944, when they were confident of victory. The vengeance weapons were launched at a time when Germany was short of trained pilots and the fuel to train them, and they were the only viable mechanisms for both delivering ordnance over enemy targets and diverting Allied raids away from German cities.

Nevertheless, frightening though the V-weapons were, had Hitler earlier invested commensurate resources in a long-range strategic bomber, he would have had far more chance of causing havoc over Britain. Alternatively, the postwar US Strategic Bombing Survey estimated that the huge resources devoted to the V-weapons program could have produced an additional twenty-four thousand fighters. German sources put the costs of the programs somewhat higher, and suggest that just for the full investment and production costs of making, for example, five thousand V-2s at twenty thousand man-hours per rocket, the Luftwaffe might have instead built well over twenty-five thousand additional Fw 190 top fighters—a figure greater than the twenty thousand 190s that were built—and that might have changed the air war over Germany, had the planes been supplied with good pilots and adequate fuel.

The German Supreme Command of the Armed Forces (OKW) was originally not told of the extent of the V-weapon programs. But even when later briefed on both the V-1 and V-2 programs, it seemed, quite understandably, underwhelmed, concluding that “the quantity of explosive which can be delivered daily is less than that which could be dropped in a major air attack.” Alternatively, had Hitler canceled the V-2 program and used its resources to focus solely on the V-1s, he might have produced well over a hundred thousand more such cruise missiles, with a far greater likelihood of inciting terror among the British population. The misplacement of resources into the V-2 program, as in a litany of other grandiose German projects, proved a disaster of enormous proportions for the Wehrmacht that even today is not fully appreciated.21

THE JAPANESE TOOK a much more macabre (albeit fiscally wiser) approach for combating Allied air superiority by substituting human lives for the staggering costs of scientific and material investment. Suicide pilots, or kamikazes (“divine winds”)—a reference to the providential storms that sank a portion of the Mongols’ fleet in the attempted invasion of Japan in 1281—probably made their inaugural systematic appearance at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, a few months after the first use of V-weapons against Britain. Japanese suicide missions, like the German rocket attacks, arose from the now-shared Axis inability to penetrate Allied air defenses to deliver bombs on Allied targets—in this case, largely the expanding US Pacific Fleet.22

Exact information on the number of attacks, losses, and results achieved is somewhat uncertain, given that only about 14–18 percent of the kamikazes that initially took off ever reached and hit their intended targets. Some missions were mixed with conventional bombing sorties. It was often difficult to attribute damage exclusively to kamikaze strikes, or even to know exactly the number of planes that were officially assigned to suicide missions, or to count as kamikazes those traditional bombers and fighters that were crippled and in ad hoc fashion crashed into their targets. Both Japanese naval (65 percent of all sorties) and army aircraft participated in the suicide attacks.23

The threefold differences between the German V-weapons and the kamikazes are instructive about the nature of strategic wisdom in World War II. First, in contrast to the terrorizing V-weapons, the Japanese attackers were capable of tactical and strategic precision, inflicting considerable damage on the American naval fleet. On average, 10 percent of the planes in each kamikaze operation were forced to turn back due to mechanical problems. Another 50 percent were shot down or crashed before nearing their target. Many either missed entirely or did little damage once they struck. Nonetheless, in the ten months of kamikaze attacks, Japanese suicide pilots struck 474 Allied warships. They killed about seven thousand Australian, British, and American sailors at a cost of 3,860 pilots and aircrews. Kamikazes accounted for about 50 percent of all US Navy losses after October 1944. Their success rate in sinking ships and killing sailors was about ten times higher than that of traditional Japanese naval bombers.24

Second, the material cost per kamikaze mission was miniscule compared to the V-weapons. Even in late 1944, Japan still possessed thousands of obsolete fighter planes. They may well have been no match for American Hellcats and Corsairs but they could make perfectly good kamikaze cruise missiles. The suicide bomber campaign in that sense drew on existing military assets and entailed far less investment in pilot skill, training, and fuel than did the conventional uses of military aircraft.

Third, given their one-way missions, the kamikaze pilots of mostly Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters were capable of a range of over a thousand miles from their homeland bases, more than five times the range of the V-weapons. The threat of suicide attacks was eliminated only when the airfields on Japanese islands were destroyed and kamikaze access to fuel, planes, and spare parts ended. Ultimately, realizing those conditions required the surrender of the Japanese government.

The kamikazes achieved their greatest successes during the US invasion of Okinawa. Given the huge concentration of American ships and their relative proximity to Japanese airfields on the mainland, the kamikazes were able to sink seventeen US warships and to kill nearly five thousand sailors—all without altering the course of the campaign. In comparison to a V-1, what the kamikaze pilot may have sometimes lacked in airspeed and size of payload was more than made up with a greater range and vastly superior accuracy. The human brain proved far more adroit in finding a strategic target than did the primitive guidance systems of the V-1 or V-2. In the narrow strategic sense, like the V-weapons, kamikazes were evolutionary and would reappear decades later (albeit in a bizarre form), most prominently in the West on September 11, 2001, when Middle Eastern suicide hijackers of passenger jets were able to do more damage at little cost inside the continental United States than any foreign enemy since the British torching of the White House during the War of 1812.25

Even with an often unskilled pilot at the controls, a kamikaze-piloted Zero fighter, equipped with a five-hundred-pound bomb, full of flammable aviation fuel, and diving at targets at speeds of over three hundred miles an hour, proved a formidable weapon. Had the kamikazes been used earlier at the Battle of Midway against just three American carriers and their thin screens of obsolete F4F Wildcats, the Imperial Navy might have forced radical changes in American Pacific strategy and prolonged the war.

There was one final kamikaze paradox. Suicide bombings were effective, but they reflected a loss of morale and desperation that indicated that the war was already irrevocably lost before they appeared.26

GERMANY AND JAPAN embraced revolutionary war planning by devoting record percentages of their military budgets to air power. Yet by war’s end Hitler was desperately searching for miracle air weapons like the V-1 and V-2 rockets and jet fighter-bombers, while the Japanese were resorting to kamikazes. This was the efflorescence of despair. Both the Germans and the Japanese conceded that it had become impossible to match American, British, and Russian conventional air fleets that had evolved to more sophisticated, and far more numerous, fighters and bombers.

The Axis regression was due to various reasons, some of which applied equally well to their eventual loss of early advantages in ships, armor, artillery, and infantry forces. Production counted. The air war was supposed to follow the pattern of many of the successful regional German and Japanese border conflicts of 1939 and 1940. Given these remarkable early successes and the inferior forces of their proximate enemies, there was less urgency to bring new fighters and bombers into mass production or to train new pilots or to study the quality and quantity of aircraft that America, Britain, or Russia was producing. Axis overconfidence was fed by ignorance of not only the aeronautical and manufacturing genius of British and American industry, but of Russian industrial savvy as well.

Take the superb Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter (33,000 built), which was partially superseded only by the Fw 190 (20,000 built). These were the two premier fighters that Germany relied on for most of the war. In contrast, in just four rather than six years of war, initial workmanlike American fighters such as the P-40 Warhawk were constantly updated or replaced by entirely new and superior models produced in always greater numbers. The premier American fighter of 1943, the reliable two-engine Lockheed P-38 Lightning (10,000 built) was improved upon by the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (15,500 built). The excellent ground-support Thunderbolt fighter, in turn, was augmented by the even better-performing North American P-51 Mustang (15,000 built) that had been refitted with the superb British Rolls-Royce Merlin engine to become the best all-around fighter plane of the war. No fighter plane made a greater difference in the air war of World War II than did the Mustang, whose appearance in substantial numbers over Germany changed the entire complexion of strategic bombing. The idea that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan might have collaborated to produce a hybrid super fighter, in the way that the British and the Americans coproduced the P-51, was unlikely.

At the same time, in the Pacific theater, initial Marine and carrier fighters like the Grumman F4F Wildcat (7,800 built) were replaced on carriers mostly by the Grumman F6F Hellcat (12,000 built) and on land by the Vought F4U Corsair (12,500 built). The Corsair had proved disappointing as an American carrier fighter, but the British, in the manner they had up-gunned the Sherman tank into a lethal “Firefly” and reworked the Mustang into the war’s top escort fighter, modified the Corsair to become a top-notch carrier fighter. Neither Germany nor Japan had any serious plans to bring out entirely new models of superior fighters built in larger numbers than their predecessors. After the war, Field Marshal Keitel admitted that the Third Reich had not just fallen behind in fighter production but in quality as well: “I am of the opinion that we were not able to compete with the Anglo-Americans as far as the fighter and bomber aircraft were concerned. We had dropped back in technological achievements. We had not preserved our technical superiority. We did not have a fighter with a sufficient radius.… I refuse to say that the Luftwaffe had deteriorated. I only feel that our means of fighting have not technically remained on the top.”27

Resources and geography played key roles. German industry was bombed systematically by late 1942, and Japanese factories by late 1944 and 1945. For all the problems with the Allied bombing campaign, no one denied that, in its last months, heavy Allied bombers finally took a terrible toll on Axis aircraft production, transportation, and fuel supplies. The availability of fuel proved the greatest divide between Axis and Allied air power. Once the Americans and the British by 1944 had successfully focused on targeting German transportation, oil refineries, and coal conversion plants, and the US Navy had made it almost impossible for Japanese tanker ships to reach Japan from the Dutch East Indies, and as Axis prewar fuel stocks were exhausted, then pilot training hours, the key for maintaining air parity, plummeted. The Germans and Japanese soon fielded green pilots, often in planes that were poorly maintained, against far better trained American and British counterparts.

Given the transfer of much of the Russian munitions industries across the Urals, the end of most serious Luftwaffe conventional bombing of Britain by 1941, and the safety of the American homeland, Allied aircraft production was always secure. It did not matter much that by 1944 the Germans and Japanese were miraculously turning out nearly seventy thousand airframes per year, when the Allies were producing well over twice that number and usually of better quality. German and Japanese aircraft and pilot increases were perhaps sufficient to maintain control of an occupied Europe and the Pacific Rim, but not to wage global war against the industrial capacities of America, Britain, and Russia.28

While the quality of planes was always crucial, even more important was the quantity of good enough warplanes put into the air. At the beginning of the Pacific war, the Japanese Zero, and at the end of the European wars, the jet-powered Me 262 Swallow, proved the best fighters in the world. But the former was of relatively static design and was obsolete by 1943. The latter was unreliable and scarce. The fact that the vastly superior American F6F Hellcat and F4U Corsair were produced in twice the numbers in half the development time of the Japanese Zero does a lot to explain the early American acquisition of air supremacy in the Pacific.29

German Me 262 jet fighters—the air equivalent of the superb but often overly complex and far too expensive Tiger tank—were never produced en masse (1,400 built) nor were they supplied with sufficient fuel or maintenance crews. Their runways were by needs long, and thus made easily identifiable targets for marauding American and British fighter-bombers. The novel jet engines of the Me 262 had a short lifespan, and repair and maintenance were complicated and expensive. It took German pilots precious months to calibrate the proper use of jet aircraft, and, against Hitler’s initial wishes, to focus on destroying Allied heavy bombers rather than using the Me 262 as a multifaceted bomber, ground supporter, or dogfighter. The relationship between early jet aircraft in World War II and late-model, high-performance, piston-driven fighters was analogous to fifteenth-century firearms and archery: gunpowder weapons were harbingers of a military revolution, while bows were at an evolutionary dead end. Nonetheless, as far as cost-benefit analyses and ease of use and maintenance, bows for a while longer were preferable to early clumsy harquebuses for widescale use.

Superb German fighters such as the Bf 109 and Fw 190 were updated and built in enormous numbers (almost 55,000 total aircraft). Yet their combined totals were still inferior in aggregate to Supermarine Spitfire, Yakovlev Yak-9, North American P-51 Mustang, and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter production—aircraft that proved roughly comparable in combat.30

The vaunted Luftwaffe, in truth, was the most poorly prepared branch of the German military, both on the eve of and during the war, and it eroded as the war progressed and its allotment of German resources declined. Its various planners from Ernst Udet to Hermann Goering were incompetent and often unstable. (The drug-addicted, obese, and sybaritic Goering, for example, once purportedly floated the idea to Albert Speer of building concrete locomotives, given shortages in steel production.) German air planners were too long taken with the idea of using large two-engine bombers as tactical dive bombers. German strategic bombing was not so much an independent entity as an adjunct to tactical ground support. The Luftwaffe was asked to make up for the intrinsic deficiencies of the nearly four-million-man ground force that invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. Had the invaders been fully motorized and uniformly and amply equipped with the latest German tanks, an independent Luftwaffe might have been freed to range ahead of the army to attack industry and transportation and swarm over the landscape to hit Soviet airfields, given that Soviet air defenses paled in comparison to what the Germans had just faced over Britain.31

Poorly designed planes like the two-engine heavy fighter Me 210 (fast, unreliable, and dangerous, only 90 finished), or its better-performing successor the Me 410 (about 1,200 produced), were rushed into production to replace increasingly obsolete heavy fighters like the Me 110, but usually proved vastly inferior to single-engine, high-performing, late-model Spitfires and Mustangs. For all its ingenious designs, experimental aircraft, and habitual gigantism, the Luftwaffe still had no workhorse transport comparable to the superb multifaceted American Douglas C-47 Skytrain (“Dakota” in the RAF designation), which was reliable, mass-produced (over 10,000 built), and rugged. The otherwise adequate German Junkers Ju 52 transport was slower, carried less payload, and was built in less than half the numbers of the C-47. Most aeronautical breakthroughs—navigation aids, drop tanks, self-sealing tanks, chaff, air-to-surface radar—were put to the greatest and most practical effect by the Allies.32

By 1943 the Allies had far more effectively concentrated on the training and the protection of their pilots. They focused on using their most experienced airmen to instruct new cadets, rather than sacrificing their accumulated expertise through continuous frontline service until they inevitably perished. Far larger air academies and longer training regimens often meant that more American, British, and even Russian pilots by the end of 1943 had more air time than their Axis counterparts. By war’s end, US fighter pilots, for example, had three times more precombat solo flight time than their Axis enemies. That fact may help explain why they had shot down their German counterparts in air-to-air combat at a three-to-one aggregate ratio.

The ability to take off from and land on a rolling carrier deck required lengthy training. Japan never quite recovered from the slaughter of its superb veteran first-generation carrier pilots in 1942 at the Coral Sea, Midway, and a series of carrier encounters off Guadalcanal. It made no adequate long-term investment in expanding new cohorts to replace the diminishing numbers of the original “Sea Eagles,” Japan’s elite corps of highly trained carrier pilots, or hundreds of the navy’s land-based fighter pilots, even though the destruction of American carrier forces was key to long-term Japanese strategy.33

In moral terms, there is no difference in the losses of soldiers in particular branches of the military. In a strategic calculus, however, the deaths of skilled pilots represented a far greater cost in training and material support than did the losses of foot soldiers. Somewhat analogous to lost skilled naval aviators at the Coral Sea and Midway, for instance, were the high fatalities of trained Turkish bowmen at the sea battle of Lepanto between a coalition of Christian polities and the Ottomans. While the Ottoman sultan was able to replace his galley fleet that was all but destroyed in 1571 off the western coast of northern Greece, it proved far more difficult to train and replace thousands of skilled archers, a fact that may explain the reduced Ottoman offensive operations in the central and western Mediterranean over the next few years. This was a lesson that the Japanese began to learn, to their sorrow, only during late 1942.34

The ability to build runways ex nihilo in newly conquered territory became an American specialty. The huge bases on the Marianas, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, or in recaptured France, Italy, and Sicily, were unmatched by any comparable Axis effort. When the Germans began the Battle of Britain, many sorties operated from makeshift French bases that lacked concrete runways and made takeoffs and landings unnecessarily hazardous. Japanese veteran pilots and aircraft engineers lamented the vast differences between US and Japanese air base construction: “It was obvious that the ability of American engineers to establish air bases wherever and whenever they chose, while Japan struggled against the limitations of primitive methods and a lack of material and engineering construction skill, must affect the final outcome of the war to no minor degree in favour of the United States.”35

Only carrier planes had allowed Japan to attack American assets from Pearl Harbor to Midway, in a way impossible with its infantry or battleships and cruisers. In turn, later US island hopping that led to an encircled Japan was spearheaded by a huge naval air force. Similarly, once air supremacy was achieved in the months before the D-Day landings in Normandy, the presence overhead of far more numerous and often better fighters made it possible for the American army to reach Germany in less than ten months, in a way perhaps otherwise impossible given the numbers and quality of its armor and infantry.

There was no better investment for the Allies by late 1944 than putting a young pilot of twenty-one years, with nine months of training, in excellent, mass-produced, and relatively cheap fighters and fighter-bombers such as the Supermarine Spitfire, Hawker Typhoon, Yak-9, Lavochkin La-7, P-47 Thunderbolt, or P-51 Mustang. The latter light, all-aluminum, and low-cost plane could fly as high as forty thousand feet, and when equipped with drop tanks enjoyed a roundtrip range of two thousand miles, while achieving maximum speeds of 437 miles per hour at twenty-five thousand feet. Roving packs of such fighters helped to neutralize superior German armor and more experienced infantry, and finally allowed heavy bombers to devastate Germany. After arriving at the Western Front in 1944, the veteran German Panzer strategist Major General F. W. von Mellenthin despaired that German Panzers could not operate in France as they had in the East, given American fighter-bombers: “It was clear that American air power put our panzers at a hopeless disadvantage, and that the normal principles of armored warfare did not apply in this theater.” Meanwhile, in the vast expanses of the Pacific, Corsair and Hellcat fighters in about a year systematically reduced the Imperial Japanese naval and land tactical air forces to irrelevancy, and rendered the Pacific a mostly American and British domain.36

Strategic bombing has become perhaps the most contentious issue of all the controversies surrounding the conduct of World War II. Nevertheless, on some points the use of high-altitude bombers solicits surprising unanimity. Its use by all sides in the early war was not initially as cost-effective in terms of achieving immediate results as the employment of fighters and fighter-bombers in tactical and ground-support operations. It failed to defeat Britain, either materially or psychologically. It did not play much of a role in the initial success of the German invasion of the Soviet Union or the Russian defeat of the ground forces of the Third Reich in East Europe. Japan never bombed China into submission. The Anglo-American strategic bombing effort over Europe did weaken and finally ruin Germany, but mostly in the last months of the war, and after enormous losses of aircraft that were the result of often wrong-headed and anti-empirical Allied dogmas.

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey released findings that the American bombing of the Third Reich had been successful but costly: forty thousand aircrew members dead, six thousand aircraft lost, and $43 billion spent. It found bombing was quite successful in some areas (e.g., oil, truck production, transportation), while less so in others (e.g., ball bearings, aviation production), prompting the debate to grow heated and yet more nuanced, raising far more questions than providing answers. Assessments of the role of strategic bombing sometimes became paradoxical: the victims on the ground often claimed that it had won the Allies the war, while the victors in the air downplayed their own achievements. Tracking German monthly industrial output was not an accurate assessment of Allied air power if it did not consider models of what German production might have been without the damage done by strategic air power. In other words, the infamous efforts of Albert Speer to draft forced labor and disperse factories ultimately proved unsustainable, given that the enormous disruptions in the German economy caused by bombing would have led to its eventual collapse anyhow had the war gone on beyond mid-1945.37

The Allies launched a number of disastrous attacks between 1939 and early 1944, including especially the failed British raids against Berlin in November 1943 through March 1944 (2,500 bombers damaged or lost), the calamitous American raid in August 1943 on the Romanian oil fields at Ploesti (100 B-24s damaged or lost), and the twin American attempts in August and October 1943 to knock out the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt, Germany (nearly 350 B-17s damaged or lost). In a tragic sense, the failures may have provided some of the lessons and experience that improved Allied bombing operations and eventually led to the destruction of German cities in late 1944 and 1945. Without a major second front against German-occupied northern Europe, it was unclear exactly what the Allies were to do—aside from North Africa, Sicily, and Italy—to convince the Soviet Union and their own publics that they were in equal measure damaging the Third Reich.

The bombing campaign in geostrategic terms helped to keep together the Allied alliance, especially at a time when an early cross-Channel invasion promised to Stalin would have been a disaster. Moreover, the sudden improvement of the Red Army’s westward advance in late 1943 and 1944 often correlated to transfers from the Eastern Front of thousands of German artillery platforms and Luftwaffe fighters to defend the Third Reich from Anglo-American bombers. That the Nazis reallotted new military production and manpower to the anti-aircraft missions rather than to bolstering ground forces against the Russians was also fundamental to the Red Army’s recovery.

In the West, a rather small and sometimes inexperienced Allied expeditionary force was able to reach central Germany in less than a year largely because German industry was short on fuel and rail facilities, and because even its most sophisticated new armored vehicles became constant targets of air assaults from their fabrication in factories to their transport to the front. In addition, the investment in planes, fighters, and support personnel, along with the vast losses accrued, nevertheless caused the enemy to incur astronomical air defense and civil defense costs, even in areas that were not further targeted for assault. By 1943, for example, Britain had spent the equivalent of nearly $2 billion in its civil defense forces, largely in reaction to fears of another Blitz; Germany invested even more on defense against bombing.

Allied area bombing not only led to the dispersal of factories and disrupted transportation hubs in Axis cities but also wore on the social cohesion necessary to fuel the war effort. Without the bombing it is hard to envision how the Allies could otherwise have thwarted the Axis war economies before their ground forces reached the homelands of Japan and Germany. By 1944 thousands of innocent civilians in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific were daily being gassed, shot, starved, and tortured by occupying German and Japanese ground forces. Without area bombing—that is, had the British emulated American daylight “precision” bombing operations, and likewise had the Americans kept B-29s at high altitudes on traditional precision missions over Japan in 1945—the war may well have been prolonged to 1946. If so, the additional combat casualties and civilian executions and deaths could have approximated the numbers of German and Japanese civilians who did perish in Allied area bombing.

There are still no definitive answers to these strategic and humanitarian dilemmas. Until there are, it remains difficult to dismiss the contribution of strategic bombing to the accelerated ruination of Germany and the surrender of Japan. In reductionist terms, the side that flew heavy bombers in numbers (and had the oil to fuel them) won, and the side that did not, lost; even more starkly, the side that could not build a four-engine bomber sacrificed strategic range and lost the war. For all its qualifications, the Strategic Bombing Survey offered a guarded final verdict of success:

The achievements of Allied air power were attained only with difficulty and great cost in men, material, and effort. Its success depended on the courage, fortitude, and gallant action of the officers and men of the air crews and commands. It depended also on a superiority in leadership, ability, and basic strength. These led to a timely and careful training of pilots and crews in volume; to the production of planes, weapons, and supplies in great numbers and of high quality; to the securing of adequate bases and supply routes; to speed and ingenuity in development; and to cooperation with strong and faithful Allies. The failure of any one of these might have seriously narrowed and even eliminated the margin.38

When one side built three times as many quality aircraft as the other, and by war’s end trained more than ten times as many pilots, then victory in the air from the mid-Atlantic to the Chinese border was nearly assured—and with it victory on the ground as well.

PLANES CHANGED THE face of battle in World War II, but ancient ideas of sea power and maritime control still governed how a nation’s assets, air bases included, would be supplied and protected, as well as enhanced across the oceans. The planet was surrounded by atmosphere, the unlimited space of air power; yet the seas still covered 70 percent of the earth’s surface. Whereas even the longest-ranged aircraft of World War II could rarely fly more than three thousand miles without landing to refuel, capital ships could range five times that distance on their original fuel allotments. When navies did refuel, it was often while in transit—an operation impossible in the air for World War II aircraft—insuring ships an independence and autonomy unavailable to air power.

When the war broke out in 1939, the British and the Americans possessed respectively the largest and second-largest fleets in the world. A mystery of relative sea power in World War II is why the Axis powers, which all believed in the strategic goal of some sort of naval supremacy, assumed on the eve of their respective aggressions that they could defeat superior navies. In that context, a theme of the following three chapters is again incongruity: both Germany and Japan thought that technological superiority—manifested in the first case by a sophisticated U-boat fleet, and in the second by the world’s largest carrier force—might trump British and American numbers, especially as expressed in battleships. In the end, however, the supreme commands of the Axis powers wasted their scarce assets in building huge and nearly obsolete battleships and cruisers, while their more innovative enemies deployed the most modern and powerful submarines and carriers in the world.