12

The Western and Eastern Wars for the Continent

BETWEEN 1939 AND February 1943 Germany launched a number of successive ground offensives, nine of which involved countries that the German army had either surprise attacked successfully or had belatedly intervened into during ongoing conflicts: Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Low Countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg), France, Yugoslavia, Greece, the British in North Africa, and the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the so-called Winter War saw the Red Army invade Finland (November 30, 1939–March 13, 1940). Yet two continent-wide offensives radically changed the course of the entire war, one ending in June 1940 at Dunkirk on the Atlantic Ocean and the other at Stalingrad in February 1943 on the Volga River, over two thousand miles distant.

Because Germany had started World War II and was the most powerful member of the Axis alliance, how its ground forces fared in these two campaigns on the European continent determined the course of the war. Whereas the Americans, Italians, Japanese, and Russians all had watched carefully the pulse of the Third Reich’s initial border wars that took place in a circumference around the Third Reich, it was the defeat of France and the later surprise assault on the Soviet Union that determined the trajectory of the war in Europe and to some extent in the Pacific as well. As a general rule, when the German army ground up its neighbors, it earned the eventual participation in the war of its opportunistic partners, Italy and Japan, and for a time the Soviet Union as well. And when the army stalled in Russia, its hold on its alliance weakened and its operations elsewhere in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy felt the aftershocks.

Another theme characterized the two great European continental wars against France and Russia: the French army, the presumed principal obstacle to German expansionism, crumbled in weeks, while the assumed incompetent Red Army ended up in Berlin. Never in military history had a great power so overestimated the ability of one existential enemy while so underestimating the capability of another. The meat grinder of the Western Front in World War I was replayed in World War II in the East, and the collapse of the Eastern Front in 1917 and the ensuing vast German occupation of 1918 was somewhat repeated in the West in 1940.

The “strange defeat” of the huge French army in June 1940—a catastrophe still inexplicable nearly eighty years later—recalibrated the entire strategic course of World War II. When the war broke out in September 1939, the Wehrmacht had been fixated on one chief enemy: the indomitable French army that had two decades earlier spearheaded the Allied victory over the Kaiser’s forces on French and Belgian soil. France, as Hitler frequently expressed in Mein Kampf, was considered the chief stumbling block to German efforts to reassert European preeminence, and it was determined to put its resources into ground forces at a time when other democracies like the British (and soon the Americans) were investing more in strategic air power and carriers. The French, it was felt, might bend but once more would be hard to break. They certainly would fight on their home soil (they had no intention of a serious preemptory attack on Germany’s western flank in 1939) far more fervently than did the Danes, Norwegians, or Poles. In the Finns’ dogged resistance to the often poorly planned and conducted Soviet invasion during the Winter War, the Germans had already seen what highly motivated troops on the defensive might do to a much larger, modern-equipped invader. But defeat the French army in the North, the Germans believed, and much of the country would then be neutralized, while the rest of continental Western Europe would fall to the Third Reich and the specter of a two-front ground war would all but end. The chief German paradox of World War II was that it feared the French in 1940 far more than it did the Russians in 1941. But by any fair material or spiritual barometer, the Red Army had greatly improved over the tsar’s military—just as Napoleon had reenergized the calcified armies of the ancien régime—and was demonstrably the far greater danger to the Wehrmacht.

French population (50 million) and industry (1938 GDP of about $186 billion) were smaller than the Third Reich’s (80 million, GDP of $351 billion), even before the second round of German conquests and occupations of 1939 and early 1940. The French understood demography as fate, and so had begun to rearm earlier than had either the British or Americans. By May 1940, they fielded an extraordinarily large army of over three million men and nearly 3,500 tanks. On paper, the French armed forces appeared just as formidable as their heroic predecessors that stood at Verdun, especially in the quality of their fighter planes and tanks. The investments in the Maginot Line were controversial but nonetheless had resulted in a nearly impenetrable three-hundred-mile wall of defense from Switzerland to Luxembourg, protecting the most accessible pathway into France from Germany. The bulwark also freed up greater numbers of French troops to deploy to the north and east on the mostly unfortified Belgian border. Paradoxes followed: the general defensive mentality instilled by the Maginot Line hampered the offensive spirit needed where its protection stopped, even as the French feared walling off and isolating their Belgian ally to the north that nonetheless could offer no guarantee of keeping the Germans away from France. Even Hitler had assumed that avoiding the Maginot Line and barreling through the top-third of France in May 1940 would be only the first phase in a long war of attrition lasting well into 1942. Most at OKW envisioned occupying northern France with a static front against a rump state to the south.1

Much of Hitler’s fear of France and dismissal of the Soviet Union derived from his own past experiences as a foot soldier and the lack of reliable intelligence about the interior and defenses of the Soviet Union. In World War I, Hitler had fought and lost in the West and assumed that other Germans, no better than he, had won on the Eastern Front due only to weaker opposition.

He and his generals understood Western Europe well and feared the technology of the Allied militaries, especially French tanks and fighters, and British bombers. In contrast, the Nazi leadership was later continually amazed about the source of Russian weapons, as if the unimaginable Soviet losses of 1941–1942 should have magically exhausted the huge reserves of the Red Army. In a March 2, 1943, diary entry, Goebbels noted of a conversation with Goering, head of the Luftwaffe, that “he [Goering] seemed to me somewhat helpless about Soviet war potential. Again and again he asked in despair where Bolshevism still gets its weapons and soldiers.” The Nazis also prioritized France because they hated socialist democracy at the same time that they had a perverse admiration for Soviet totalitarianism, Bolshevik though it was. Hitler repeatedly expressed his respect for the career and methodologies of his onetime collaborator Joseph Stalin, whose connivance between August 1939 and June 1941 had allowed him to turn westward, but he held only contempt for Western statesmen, consistent with his system of values that calibrated morality by degrees of perceived ruthlessness.2

Western Europe represented less than 20 percent of the landmass of the Soviet Union. Most important, it possessed good roads and standardized rails, and lacked the room of Russia in which invading armies might be swallowed up pursuing retreating forces. The battlefields in the West were near the German Ruhr. Resupply was easy compared to sending material across the expanse of the Ukraine. Familiarity between the French and the Germans, both being of a kindred Western European heritage, meant that the war likely would lack the barbarity of the later Eastern Front. Those surrounded would likely surrender, because they had hopes of being treated with “European” humanity. Hitler apparently believed that in any future war the Soviets would fight well, and yet the Wehrmacht would easily prevail because of Russian backwardness; in contrast, the French might not fight as well, but might still hold out because of their comparable arms and experience. That mostly the opposite occurred explains much of the strange war that followed.

On May 10, 1940, Hitler invaded Belgium, France, and the Netherlands with over three million men, nearly twenty-five hundred tanks, and over seven thousand artillery guns. Yet the targeted Allied western democracies in response could in aggregate muster more men, armor, and planes. That fact had initially spooked the planners of the German High Command, who also were concerned that half their conscript invading army had little experience or training. And they had further reasons to worry, because two-thirds of German tanks had proven already obsolete after just nine months of war. Mark I and II Panzers, still the vast majority of German armor, were clearly inferior to the majority of French armored vehicles.

France, given its far smaller territory and lack of sizable Lend-Lease shipments, by itself was incapable of rebounding to mobilize the vast manpower or industrial reserves that later characterized the Soviets’ recovery from invasion in 1942–1945. For a variety of self-interested reasons, Belgium, Britain, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Norway had never coordinated well their respective forces or munitions industries, and so their paper strength always proved a chimaera. After the destruction of Poland and Czechoslovakia, the small Western democracies had either hoped to fight from fixed positions or expected that Hitler would turn his attention mostly to their British or French neighbors.

It was never the prewar British intent to deploy vast ground forces in the West for a joint defense of French soil at the levels characteristic of 1914–1918 (between 1.5 and 2 million troops), and so Britain kept its air and expeditionary ground commitments at somewhat over three hundred thousand soldiers by May 10, 1940. Most of the divisions that were sent were hastily mobilized, largely untried, and ill-prepared. General Alan Brooke, commander of the British II Corps, admitted in November 1939: “On arrival in this country [France] and for the first 2 months the Corps was quite unfit for war, practically in every aspect.… To send untrained troops into modern war is courting disaster such as befell the Poles.”3

The French military had poor communications, with few radios to coordinate armored infantry and air support. Confused and aged officers were not nearly as able to use their formidable assets as were the Germans. Later General Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma attributed the German armored victory to concentrations of force, especially to tanks and planes blasting away corridors of resistance, rapid movement during the night, and autonomous mobile columns that brought their own fuel and food. Marc Bloch, the legendary French historian and combat veteran of the defeat, agreed: “The ruling idea of the Germans in the conduct of this war was speed. We, on the other hand, did our thinking in terms of yesterday or the day before. Worse still: faced by the undisputed evidence of Germany’s new tactics, we ignored, or wholly failed to understand, the quickened rhythm of the times.”4

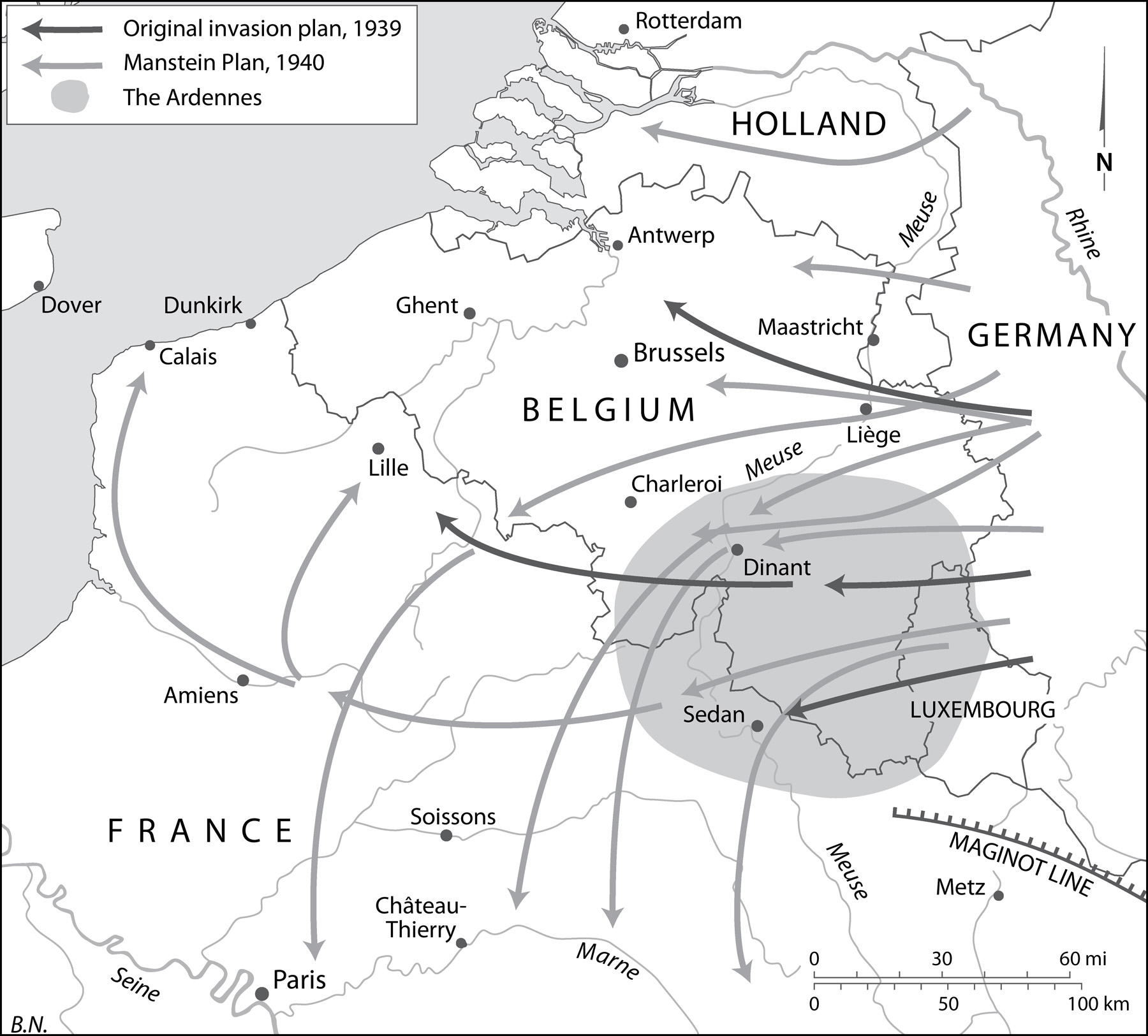

The German General Staff had advanced and rejected various (and mostly predictable) plans of attack before agreeing on a more unexpected approach, in part due to fears that original, traditional agendas of a broad assault had been compromised and that their plans had fallen into the hands of the Allies. The quite radical element of the new version of attack, the so-called Manstein Plan, was a central strike through the supposedly rugged Ardennes Forest into Belgium—well above the Maginot Line—and an assumption that once the Allies saw that they were not so much outflanked to the north in Belgium but rather sliced by sickle cuts from behind through the Ardennes, strategic chaos would follow. Sending the smaller Army Group C to the south against the Maginot Line would cause most of the French forces not trapped near Belgium to fear being caught in another pincer. Cutting the larger Allied defenses in two, the Germans would emerge from the forest and push to the coast. The Allies who were stacked on the Belgian border would be cut off from their communications with most of France to the south and be driven to the sea.

At first glance the German plan seemed irrational. The British and French together could send up superior air cover. The Dutch and Belgians were not quite paper tigers; together they had adequate arms and would be fighting on familiar terrain, perhaps on the flank of the Germans while the Wehrmacht’s main force struggled through forests and crossing rivers. The vast majority of French territory to the south would be still untouched by war, its factories and manpower reserves free to send in newly equipped armies.

Yet after the Ardennes surprise, the French-British force collapsed in six weeks. In retrospect, the reasons for this stunning defeat seemed manifold: antiquated French tactics of static defense; the lack of a muscular and mobile central reserve; a failure of the British, French, Belgian, and Dutch defenses to coordinate their efforts; inadequate communications and poor morale—all the wages of a decade of appeasement and more than eight months of sitting after the invasion of Poland, along with a fossilized high command of aged generals. Marc Bloch again summed up the collapse of Western Europe as a “strange defeat,” given that the Wehrmacht invaded France with almost a million men fewer than the aggregate number of men under arms in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and the British Expeditionary Force, as well as a shortfall of over four thousand artillery pieces and one thousand tanks. On the eve of the invasion, the French military had been steadily growing, while the Germans were still replacing equipment from the campaigns in Poland and Norway.

French author (and later resistance fighter) André Maurois remarked of the abrupt collapse:

The myth of the enemy’s invincibility spread rapidly and served as an excuse for all those who wanted to retreat. Terrifying reports preceded the motorized columns and prepared the ground for them.… the city was buzzing with rumors: ‘The Germans are at Douai.… The Germans are at Cambrai.’… All this was to be true a little later; at the moment it was false; but a phrase murmured from shop to shop, from house to house, was enough to set thousands of men, women and children in motion, and even to startle military leaders into ordering their detachments to retire toward the coast, where as it turned out they were captured.

All this defeatism was a long way from Marshal Ferdinand Foch’s famous defiance regarding his embattled French forces at the First Battle of the Marne, some twenty-six years earlier, “my center is giving way, my right is retreating, situation excellent, I am attacking.”5

The Germans had planned an armored attack that had never been tried by an army on such a vast scale. The huge invading force, in characteristic German fashion, was divided into three groups (A, B, and C). And the senior army group commanders—Gerd von Rundstedt (45 divisions), Fedor von Bock (29 divisions), and Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb (18 divisions)—were the Wehrmacht’s superstars. Von Rundstedt and von Bock had supposedly already changed the face of battle in Poland the prior autumn and now were charged with conducting large encirclements on an even grander scale. Group B was to rush into the Low Countries to tie down and push back the British and northern French Armies, with Group A barreling through the Ardennes to split the Allied armies in two. Group C planned to assault the Maginot Line while preventing counterattacks from the south on the Germans’ northern flanking movements.

The French had believed that the legendary impenetrability of the Ardennes made it a natural extension of the Maginot Line, perhaps because they assumed all motorized divisions were as cumbersome as their own columns. In fact, the “mountainous” forest of the Ardennes (cf. Latin arduus, “steep”) was mostly less than two thousand feet in elevation. It was not nearly as impassable as its reputation suggested. Generals Heinz Guderian, a Panzer group commander, and Erich von Manstein, a staff planner and corps commander, both felt that the Ardennes, in fact, offered an open doorway to the coast. The idea that the Germans would dare attack through both the mountains and against the Maginot Line would only enhance their reputation for audacity and contempt for conventional military wisdom. The realization that Germans were streaming in where they should not have, caused immediate panic. “The war,” Marc Bloch later wrote while a prisoner of war, “was a constant succession of surprises. The effect of this on morale seems to have been very serious.” A year later, a similar surprise three-part plan of attack under the same three army group commanders would mark the invasion into the Soviet Union.6

Blitzkrieg in France

The sudden surrender of a half million stunned French troops on June 22 all but ended the Battle of France. But there were still far more armed French troops in the center and south of the country, and almost as many potential partisans—the nucleus of a national resistance that might have turned rural France into what later followed in Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito or in central Russia. However, few French leaders called for a guerrilla war, or even for a concentrated retreat to a redoubt in the south. The better of the World War I French generals (Louis Franchet d’Espèrey, Ferdinand Foch, and Joseph Joffre) were dead, and the most innovative by French standards were too young or in 1940 lacked sufficient rank (Charles De Gaulle, Henri Giraud, Philippe François Leclerc, René-Henri Olry, Jean de Lattre de Tassigny). It was difficult to judge which of the commanding aged French generals—Maurice Gamelin (67), Alphonse Joseph Georges (64), Maxime Weygand (73)—proved the most defeatist. The French largely accepted the collaborationist visions of Marshal Philippe Pétain (84) rather than wishing to emulate the Finns. General Alan Brooke, veteran of World War I in France, an admirer of the French, and a British liaison officer with the French military in 1939, also despaired at the prewar French army’s lack of morale: “Seldom have I seen anything more slovenly and more badly turned out. Men unshaven, horses ungroomed, clothes and saddlery that did not fit, vehicles dirty, a complete lack of pride in themselves or their units. What shook me the most, however, was the look on the men’s faces, disgruntled and insubordinate looks, and although ordered to give ‘eyes left’ hardly a man bothered to do so.”

Both the Western democracies (France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and the British Expeditionary Force) and the Soviet Union fielded more troops than did the attacking Wehrmacht during its respective two invasions on May 10, 1940, and June 22, 1941. Both initially had as many planes and tanks as the Germans. In many cases their arms were of similar or superior quality to those of the Third Reich. Both the democracies and the Soviets were also similarly stunned by the German army’s surprise attacks. And their generals were left demoralized and confused. What, then, was the key difference in their contradictory abilities to survive the first few weeks of blitzkrieg?

Whereas morale in the West imploded, it rebounded in the East. Historians ever since have argued over this strange disconnect, especially given the inverse experiences of World War I that had seen the democracies survive and Russia capitulate. They often correctly cite the vast expanse of the Soviet Union that allowed strategic retreat. The murderous authoritarianism of the Soviet state certainly made capitulation a capital crime. The harsh weather of Russia aided the defenders. And the chronic impoverished conditions of Russia created a desperation not found in France and the Low Countries during the post-Versailles 1920s and 1930s. Yet whatever the precise causes for such different resistance, the reactions to Hitler’s early continental wars remind us that hackneyed military aphorisms of the superiority of the moral and spiritual to the physical and material are not so hackneyed.7

Yet victory posed problems for the Germans. The Third Reich was immediately entrusted with occupying about four hundred thousand square miles of additional territory in Western Europe, in addition to governing Belgium, Denmark, Norway, and Poland. Hitler never really fully appreciated that each serial conquest in Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece required tens of thousands of occupation troops that otherwise might have served on his envisioned future front against the Soviet Union. Hitler also never comprehended German lessons of occupation after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 1918, when German control of newly acquired vast swaths of Bolshevik Russia tied down a million German soldiers, ensuring that there were not enough German troops rushed westward to stem the flow of arriving Americans into France.

Hitler in the months after the fall of France toyed with plans to demobilize thousands from the army, so convinced was he that the shock over the destruction of the once-great French army would leave the Western world in utter despondency. In private he worried over the fact that an Allied naval blockade, and years of military buildup and now war were pushing the German economy to near financial insolvency. In any case, he assumed that the Munich generation of British diplomats would soon come again to Germany for terms. Without an end to the Allied maritime embargo, most thought it unlikely that Hitler would start yet another new war with the Soviet Union, which, after all, supplied almost a third of German oil.8

Although France fell in less than fifty days and suffered over 350,000 casualties, the German army itself took substantial losses, an often-forgotten fact of the supposed walkthrough. Nearly fifty thousand were killed, later died from wounds, or were declared missing; over a hundred thousand were wounded—a six-weeks’ butcher’s bill for victory comparable to the American losses in defeat after a decade of fighting in Vietnam. The relatively rapid conquest of all of continental Europe and the war at sea between September 1939 and June 1940 had still come at the cost of a hundred thousand German dead and over three times that number of wounded. The serial wars in Poland, Western Europe, Norway, and the Battle of Britain—and more casualties to follow in spring 1941 in the Balkans—would cost the Luftwaffe over two thousand fighters and bombers, as well as hundreds of key transports.

Although undefeated in all these conflicts, the Wehrmacht was not necessarily in an improved strategic position even after the fall of France. The victory required a careful balancing act between outsourcing some occupation responsibilities to a supposedly autonomous turncoat Vichy government, at least until November 1942, and yet deploying enough soldiers (roughly 100,000) to keep resistance to a minimum. Soon the Italian army in North Africa was collapsing after a few months of fighting. Spain’s autocratic leader, General Francisco Franco—now seduced, now rebuffed by Hitler—would not bring Spain into the war, ensuring that Gibraltar would still control the western Mediterranean’s entry and exit. The Wehrmacht would learn that it could neither invade nor bomb Britain into submission. For all its successes, the frightening U-boat campaign had not cut off Britain from imported resources. In sum, there were enough worries for a depleted Wehrmacht, without attacking the Soviet Union, which now shared a border with the Third Reich—to say nothing of starting a war with the United States.

There was a final irony of the catastrophic fall of France. Within a year and a half of the French collapse, the long-term future of Europe would be more favorable to the defeated than to the victors. The free French people were to gain a generous ally in the United States, while Germany was to acquire a multifaceted enemy that it could not defeat in Russia. June 1940 was not quite the end of France; by the end of June 1945 there would be French soldiers in occupied Germany and no Germans left in France.9

THE TWO SUPERPOWERS on the Eastern Front in 1941 remained more alike than different: both were autocratic; both had no compunction about murdering millions of innocent civilians; both had made contingency plans to attack one another. Unfortunately, both de facto allies also shared a common border in occupied Poland after 1939. Germany and western Russia were the largest states in Europe. Each had huge armies and controlled a vast empire of occupied territories. Neither believed in the Western democratic notion of “rules” of modern warfare. So a land war like no other would follow on the Eastern Front.

The German army that invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, once again achieved complete initial surprise despite weeks of blatant overflights of Soviet territory, near exact Russian intelligence about the date of the impending surprise attack, serial warnings to Stalin from the British about Hitler’s planned perfidy, and the obvious massing of German troops along the Russian border. This was the third occasion, after the assaults on Poland and France, on which well over a million German soldiers had staged a three-pronged attack without warning. The Axis army of nearly four million was not just the largest invasion force in history, but also the greatest European invading army that has ever been assembled anywhere—six times larger than Napoleon’s force that took Moscow. The general plan (there was no sense of a master strategic blueprint that was sacrosanct) was to trisect the Soviet Union through vast Panzer sweeps that would encircle and destroy Western Russian armies before they could flee and regroup in the defense of Moscow and Leningrad. The army groups would enlist regional allies in their own particular geographical spheres of interest—Finns in the north, Hungarians and Romanians to the south—each spurred on by their own traditional border disputes with Russia and the possibility of recovering lost territory.10

Hitler thought the potential fruits of a victory over the Soviet Union were irresistible: the entire continental European war would now conclude in German victory, German chronic worries over food supplies and oil would fade, the position of an isolated Britain would prove nearly untenable, and Eastern European squabbles would be adjudicated by grants of Soviet borderlands. As it was, June 22 marked the beginning of the most horrific killing in the history of armed conflict, a date that began a cycle of mass death and destruction over the next four years at the rate of nearly twenty-five thousand fatalities per day until the end of the war.11

Hitler’s fantasies were to shock and awe the Soviet government into paralysis, thereby freeing up eastern living space (Lebensraum) for planned arrivals of German settlers, thus obtaining natural wealth and food for the resource-hungry Third Reich that would make Germany immune from British and American sea-blockades of key materials. A continental superstate of some 180 million citizens would supposedly be at the mercy of an eighty-million-person Reich that was already stretched thin from northern Norway to the Atlas Mountains and from the English Channel to eastern Poland.

Hitler believed that his rapid progress across the Soviet Union would likely destroy Bolshevism, subjecting supposedly inferior peoples to either mass death or slavery, and turning the Soviet Union into German-controlled feudal estates at least to the Dnieper, Don, and Volga Rivers. The Third Reich could then build a veritable “living wall” of permanently based Wehrmacht soldiers further eastward at the historic dividing line between Europe and Asia at the foot of the Ural Mountains, and let what was left of eastern Russia starve. As early as summer 1940, Hitler even went so far as to believe that by attacking Russia, and no doubt knocking it out of the war, he would relieve the Japanese of worries in their eastern theaters and thereby assist them in neutralizing the American navy that was increasingly aiding the British. In Hitler’s mind, his air force and navy had lost against Britain, but his army still remained undefeated and invincible.

Hitler also scapegoated the Soviets for supposedly falling short of their trade and commercial obligations to the Third Reich under terms of their nonaggression pact. He was especially irritated by Russian aggression in Eastern Europe, Finland, and the Baltic states, as if there should have been some honor among thieves. In early 1941, he whined to Admiral Raeder of Stalin’s demand to take all the oil of the Persian Gulf rather than divide it with the Third Reich. He resented Stalin’s apparent politicking in the Balkans with communist liberationist movements. Goering later claimed that after the Soviets’ sudden invasion of Finland, the Nazis believed that Stalin might strike them at any time. For all Hitler’s wild talk of needing resources, it nevertheless may have been true that the Wehrmacht’s mobilization and near two years of warring were becoming unsustainable without new sources of food and oil. Ex post facto, these rationales all seem little more than fantasies, but in spring 1941 to an undefeated Wehrmacht, they seemed reasonable.12

The German High Command had a bad habit of prematurely assuming victory. In July 1941, the chief of the German Central Staff, General Franz Halder famously wrote in his diary just two weeks after the start of Operation Barbarossa that “on the whole, then, it may be said even now that the objective to shatter the bulk of the Russian army this side of the Dvina and Dnieper has been accomplished. I do not doubt the statement of the captured Russian Corps CG [commanding general] that east of the Dvina and Dnieper we would encounter nothing more. It is thus probably no overstatement to say that the Russian Campaign has been won in the space of two weeks.”13

Halder would have been right if destroying large Soviet armies in western Russia and soon occupying perhaps 20 percent of total Soviet territory could be considered synonymous with the defeat of the entire Soviet Union. But the German theory of victory made sense only if one assumed that the Russians would, as expected, continue to fight as unimpressively as they had initially, or previously in Finland or Poland, or as the French had earlier—or if the German army maintained the same ratios of manpower and weaponry that it had enjoyed earlier in France. Yet there was no historical evidence that the Russian army had ever fought in lackluster fashion on its own soil as it so often did abroad. Nor were there many examples of Mother Russia ever running out of manpower to stop an invasion.

One of the chief architects of Operation Barbarossa, General Erich Marcks, had assumed in his planning that the occupation of industrialized European Russia would fatally cripple Soviet productive capacity. The sudden destruction of existing Soviet military forces would mean that replacement men and materiel would either come too late or in too small numbers to affect the outcome. German logic was that if Stalin’s initial fears of potential German power had earlier persuaded him to seek the nonaggression pact with Hitler in August 1939, then he might sue for concessions once he experienced the reality of such force used to deadly effect against western Russia. In World War I, Hitler remembered, the communists, as ideologues rather than nationalists, had been eager in March 1918 to quit the war and with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk accept almost any compromises demanded of them by the occupying Germans. Hitler entirely misread Stalinism, thinking it an incompetent globalist communist movement rather than a fanatically nationalist, and, in some sense, tsarist-like imperial project.

Despite Stalin’s foolhardy initial refusals to trade space for time, Hitler again failed to appreciate historic Russian defense strategy based on ceding swaths of territory on the assurance that the sheer size of Russia would eventually exhaust the occupier while still allowing plenty of ground for retreating Russian forces to regroup. Tsar Alexander I had famously warned the French ambassador in 1811, a year before Napoleon invaded his country, “we have plenty of space… which means that we need never accept a dictated peace, no matter what reverses we may suffer.”14

With the failure to take either Moscow or Leningrad by late 1941, or to destroy the Red Army and the Russian munitions industry, the Germans had already lost the war against the Soviet Union, making their defeat and occupation of European Russia an expendable lizard’s tail that was shed without killing the once-attached body. Each day that the Wehrmacht went eastward as summer became autumn, it became ever more anxious to end the conflict outright. As late as October 1941, the General Staff still believed it could take Moscow and win the war before winter, especially given the huge encirclements and haul of prisoners at Vyazma and Bryansk. General Eduard Wagner of the Supreme Command of the Army on October 5 wrote, “operational goals are being set that earlier would have made our hair stand on end. Eastward of Moscow! Then I estimate that the war will be mostly over, and perhaps there really will be a collapse of the Soviet system.… I am constantly astounded at the Führer’s military judgment. He intervenes in the course of operations, one could say decisively, and up until now he has always acted correctly.”

Wagner (eventually to commit suicide as a co-conspirator in the 1944 plot against Hitler) would change his rosy prognosis in less than three weeks and thereby reveal by his fickleness that the generals were just as foolhardy as their Führer: “In my opinion it is not possible to come to the end of this war this year; it will still last a while. The how? It is still unsolved.” By November 7, 1941, Hitler himself was admitting to his generals that the original objectives of Operation Barbarossa—driving the Russians east of the Volga and capturing the oil fields of the Caucasus—would not be reached in 1941. The next day in a public address at Munich he disowned blitzkrieg, which he now dubbed an “idiotic word.”15

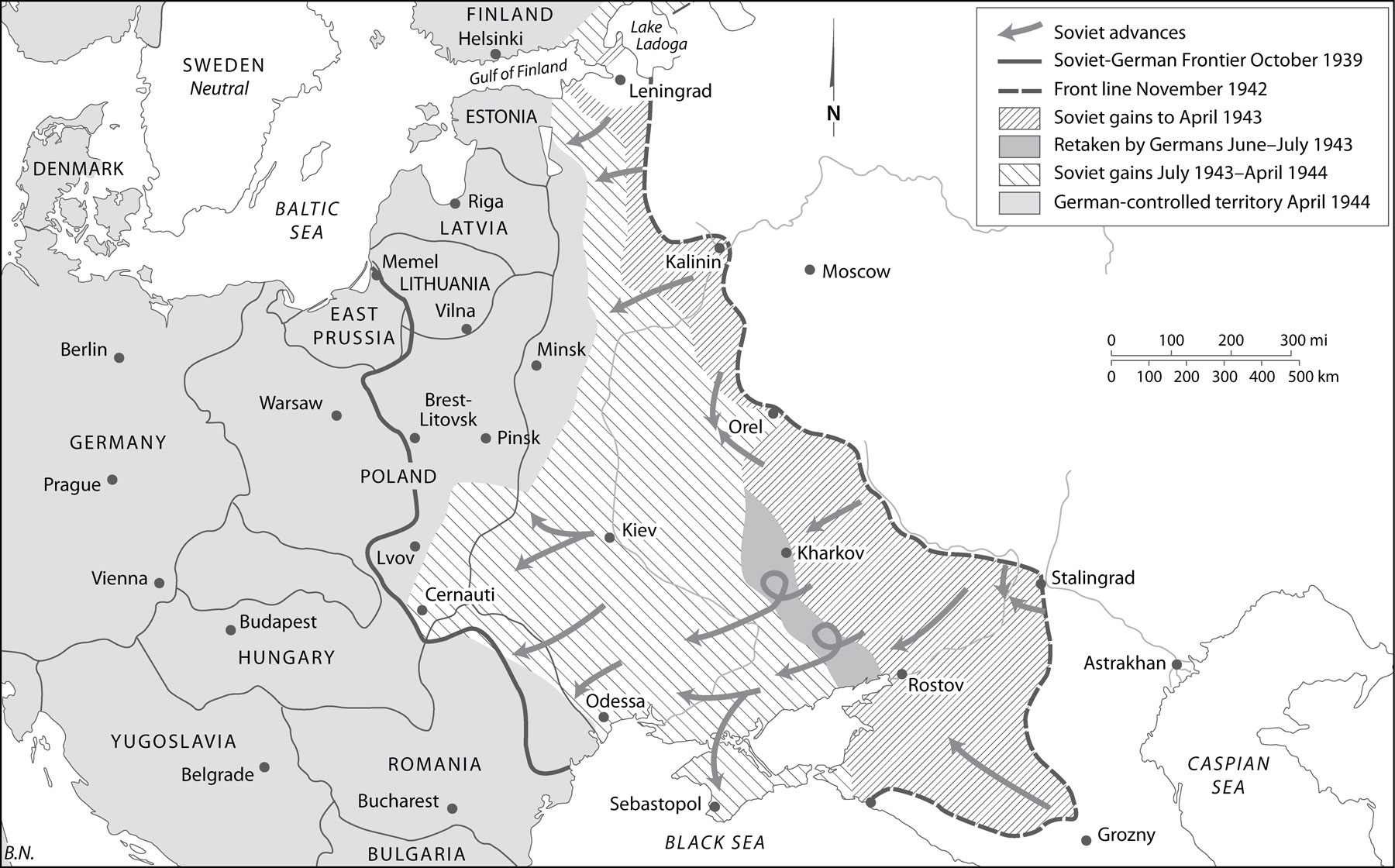

The Eastern Front saw two general phases of fighting. The brief first interlude was the initial German offensive of June 22, 1941, which stalled on all fronts in mid-December 1941. It resumed in the south in spring 1942, and ended for good in the deadly cauldron at Kursk in July and August 1943, leaving outnumbered German troops on a vast thousand-mile front from Leningrad to the Caucasus inadequately supplied, outnumbered, and facing partisan resurgences to the rear.

When most initial German offensive operations ended, the Eastern Front then entered a second cycle of stubborn and sustained Russian offensive operations, punctuated by occasional German counterattacks. The slowness of the Russian recovery in 1942–1943 illustrated the skill of an outnumbered German army on the defensive, one that gave up the same, though less familiar, territory far more slowly than had the surprised Russians in summer 1941. By 1944 the Red Army—now nearly twice as large as the German army that in turn was for a while longer still larger than when it had entered Russia in June 1941—had advanced the Leningrad-Moscow-Stalingrad line to near the borders of East Prussia and was approaching Eastern Europe. By early 1945, most of the territory of the Eastern European allies of the Third Reich was either under Soviet occupation or their governments were joining the Red Army, as Stalin prepared for the final spring 1945 offensives into Germany and Austria proper.

Hitler’s habit throughout the ground war against the USSR was to focus on Russian casualty figures rather than Russian replacements. Such adolescent thinking was characteristic of Hitler’s entire anti-empirical appraisal of Soviet air, armor, and artillery strength. General Günther Blumentritt, deputy chief of the General Staff in January 1942, noted of Hitler’s fantasies: “He did not believe that the Russians could increase their strength, and would not listen to evidence on this score. There was a ‘battle of opinion’ between Halder [chief of the German General Staff] and him.… When Halder told him of this [Russian numerical superiority], Hitler slammed the table and said it was impossible. He would not believe what he did not want to believe.”16

By German logic, the Russians should have quit like all of Hitler’s initial victims. Half of Russian tanks in 1941 were obsolete. Nearly 80 percent of Russian planes were outdated. But from the outset of the conflict the outcome did not hinge on initial German superiority but on whether Hitler’s advantages were of such a magnitude as to offset the vast geography and the huge manpower and industrial reserves of the Soviet Union. Should the Wehrmacht not knock out the Red Army in weeks, the Germans would then find themselves in a war of attrition far from home, amid hostile populations and an enemy that had manpower reserves double those of the Third Reich. Prior to Operation Barbarossa the German army had not traveled on land much beyond two hundred miles in any of its prior campaigns, and had not fought a total war since 1918.17

Within six months of the invasion, Germany had occupied nearly one million square miles, the home of fifty to sixty million Russians—between one-quarter and one-third of the Soviet population—while killing or putting out of action over four million Russian soldiers and obtaining about half the food, coal, and ore sources of the Soviet Union. Hitler ranted about his invasion being a clash between Western cvilization and the racially inferior Slavic hordes of the East. There was a scintilla of truth to his idea of a vast multinational European anti-Bolshevik crusade, at least in the sense that, of the nearly four million Axis invaders, almost a million were Finns, Romanians, Slovakians, and eventually substantial numbers of Hungarians, Italians, and Spaniards, in addition to volunteers from all of occupied Western Europe, along with scavenged trucks, tanks, and artillery pieces from now-defunct European militaries.

By 1942 the Third Reich’s eighty million people had been augmented by perhaps over a hundred million in Axis-occupied and-allied Europe, while an expanded Soviet Union’s 180 million had been reduced below 150 million due to German occupation and losses. Yet the Soviets by 1943 usually fielded a frontline army on average of about six to seven million, nearly double the size of the Axis divisions on the Eastern Front, despite losing over four million in the first twelve months of the war. The anomaly was not explicable by the fact that the Germans drafted a smaller percentage of their population. Both militaries eventually conscripted somewhere between 13 percent and 16 percent of their available manpower pools. The Soviets were also able to put more of their wounded back at the front, while enlisting some two million women in combat units. One way of understanding Operation Barbarossa is Hitler’s attempt to fight the Soviet Union on the cheap without sizable reserves of manpower and equipment—if the original invading army of four million Axis soldiers can ever be called inexpensive. He now owned the largest industrial base in the world and yet failed to fully mobilize the potential of all of Axis-occupied Europe, given that the German economy was parasitical and extracted from rather than invested in its occupied conquests.18

There were lots of other reasons why the German invasion failed. The original objective was never spelled out but was unspoken and assumed by OKW and OKH: Was it to be a direct assault on Moscow to force the protective mass of the Red Army to show its strength in one colossal battle and thus be destroyed between gigantic German pincer movements, then to ensure the capture of the iconic capital and nerve center of Soviet communism? No one knew, given that Hitler focused alternatively on the northern and southern flanks. As his generals in Clauswitzean fashion harangued that the focus of the front was Moscow where the Soviet army would swarm and thus could be surrounded and destroyed, Hitler answered with lectures on the northern industrial potential and the strategic location of Leningrad and the southern food and fuel riches of the Ukraine and Caucasus. “My generals understand nothing of the economics of war,” Hitler screamed to General Heinz Guderian, who objected to the controversial August 1941 diversion of Army Group Center’s Panzers away from Moscow to the Ukraine.

Hitler insisted that he had studied Napoleon’s failure of 1812 and therefore was not obsessed with taking Moscow (“of no great importance”), whose capture had brought the French no strategic resolution. Still, he and his staff seemed ignorant of an entire host of history’s great failed Asiatic invasions: Darius I’s Scythian campaign, Alexander the Great’s exhaustion at the Indus, the Roman Crassus’s march into Parthia, and the Second through Fourth Crusades. The impressive initial strength of all these efforts had proved hollow, given the magnitude of the geography involved, the supplies needed, and war’s ancient laws that invading forces weaken as they progress, sloughing off occupation troops, protecting always lengthening lines of supply, wearing out men and equipment as distances increase, and running out of time before autumn and winter arrive.19

Hitler’s coalition army was perhaps sufficient to take Moscow and Stalingrad, but not to divide into three separate army groups along a 750-mile front that would expand even farther from the Baltic to near the Caspian Sea. The German generals, albeit mostly later in postwar interviews, had argued that a focus on just Leningrad or Moscow might have succeeded, but the long trajectory of Army Group South toward the Volga River both in 1941 and 1942 subverted all three efforts.20

Another flaw in Operation Barbarossa was the diversion of enormous German resources for nonmilitary objectives that made the conquest far more difficult, specifically the huge military resources devoted to the Final Solution. According to Nazi logic, the so-called Jewish Question could not be fully addressed unless Hitler moved into eastern Poland and western Russia, the historical home of the vast majority of European Jews. In addition, as German casualties climbed and the war with the USSR went into its second and third years, Hitler increasingly fell back upon the self-serving rationale that the invasion had been defensive and preemptive, a desperate act to hit Stalin before he would do the same to Nazi Germany—an allegation that only scanty postwar evidence might support. Yet for once Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov told the truth when apprised of the surprise attack in its first hours by the German ambassador in Moscow: “Surely, we have not deserved that.” Yet in the end, the real reason for invading the Soviet Union may have been simply because Hitler thought that after conquering all of Western Europe and controlling most of Eastern Europe, he could do as he pleased, and do so rather easily.21

Hitler, always the captive of paradigms of World War I, found solace in the fact that Germany had defeated Russia in World War I, and with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk had stripped the infant Soviet government of one million square miles and fifty-five million of its people. In Hitler’s view, Stalin’s communism would probably not marshal sufficient Russian manpower and willpower, given that at the outset of the Soviet state, Lenin had surrendered these large swaths of Russia to Germany and Turkey in March 1918.22

After the victory in Poland, Hitler, not his generals, had rightly insisted that the Army could next wage a successful preemptory war in the West when his cautious OKW worried about supply shortages and operational deficiencies. On every occasion, Hitler, not his commanders, proved prescient, at least in the short term. In addition, the Soviets had not fought particularly impressively in the divvying up of Poland in September 1939 or the Finnish war of 1939–1940. Little was known in Germany about Marshal Zhukov’s decisive victories over the Japanese along the Mongolian border in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol, at least in comparison with Hitler’s greater knowledge of the Russian disasters of 1904–1905 and 1918, and Stalin’s mass purges of the Soviet military between 1937 and 1939 that had led to the deaths or imprisonment of half of all the officers of the Red Army. In short, overconfidence also allowed Operation Barbarossa to proceed without focusing on clear objectives.

There was a litany of unwise tactical decisions that might have been averted, well beyond the sudden redeployment of Army Group Center from its original Moscow route in August 1941 to join Army Group South in its encirclements of Kiev, and the lack of logistical preparation for operations beyond six months. Hitler ordered a siege rather than a direct assault on Leningrad, when it might have been possible earlier to have taken the city. He relieved either directly or through his senior commanders, at one time or another, the Wehrmacht’s most successful officers—von Bock, Guderian, von Leeb, von Rundstedt, Manstein, as well as thirty-five corps and division commanders alone in December 1941—often for arguing over necessary tactical pauses or withdrawals. Had the Russian winter that typically favored the defender over the attacker been more typical (a month later in onset, and of less severity), or had Hitler not gone into the Balkans in April 1941 to put down an uprising in Yugoslavia and to salvage Mussolini’s Greek misadventure, or had Hitler not declared war on the United States on December 11, or had Hitler not again divided the forces of Army Group South in summer 1942 during the drive to the Caucasus (Case Blue), then there would have been an outside chance of at least short-term success.

Soviet Advances on the Eastern Front, 1943-1944

All those “what ifs” cloud the reality that Germans were also a northern people who should have known as much about winter conditions as the Soviets. In the 1933 training manual of the German Army, officers were advised that “ears, cheeks, hands, and chins must be protected during cold weather.” Besides additional warnings about proper clothing and supplies, the manual emphasized that “winter equipment requirements for men and horses must be planned well in advance.” Nor was the Soviet Union an exotic Ethiopia or even a distant United States. Instead, it was a known commodity, a nation that had been more or less allied with Hitler since August 1939, and one that had enjoyed military cooperation dating back to the early 1930s. The idea that Hitler may have had no clue about the existence of the T-34 tanks is ipso facto an indictment of the entire mad idea of invading the Soviet Union without adequate intelligence. And the problem with Operation Barbarossa was not so much diversions and redirections of German armies, but the lack of sufficient manpower and equipment for such a vast enterprise in the first place.23

HITLER’S DECEMBER 11, 1941, declaration of war on the United States soon proved cataclysmic to German fortunes of the Eastern Front. The serious American strategic bombing that commenced in late 1942, along with Britain’s ongoing effort, would eventually divert well over half the Luftwaffe’s fighters from ground support in Russia to high-altitude bomber interceptors over Europe. Worse still for German ground troops, by 1943 German aircraft production had flipped, for the first time producing more fighters for the home front than ground-support bombers for the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front. At least fifteen thousand superb field guns of various calibers likewise would be kept home outside German cities as flak defenses against Allied sorties, robbing the army of too many of its most effective weapons against Soviet tanks. Ten percent of the entire German war effort was devoted to producing anti-aircraft batteries and ammunition, and well over 80 percent of all such guns were deployed inside the Third Reich against British and American bombing attacks.24

One of the many reasons why the Luftwaffe could not supply the trapped Sixth Army at Stalingrad—aside from the weather, fuel shortages, and anti-aircraft batteries—was the inability to make up for the prior losses of transport planes during the invasion of Crete, and the later costly efforts at resupplying the Afrika Korps in Libya. For all Stalin’s snarling attacks from 1941 to June 1944 on the British and Americans for failing to open a second front, the sudden rapidity with which the Red Army went on the offensive in 1943 was in part due to transfers of German resources from Russia back to the Mediterranean and the German homeland.25

An instructive way of understanding the historical role of Operation Barbarossa in determining the outcome of World War II is to consult General William Tecumseh Sherman. Even after the capture of Atlanta, he had forecast that the American Civil War would not end until the South’s elite fighters were killed: “I fear the world will jump to the wrong conclusion that because I am in Atlanta the work is done. Far from it. We must kill those three hundred thousand I have told you of so often.” What Sherman saw had to be done to the Confederate army was done to the Wehrmacht by the Red Army at the cost of well over eight million of its own soldiers between mid-1941 and early 1945. It neutralized what by all consensus was the best fighting force in the history of land warfare, albeit often unwisely and with unnecessary costs. At times the Soviet army committed nearly as many horrific atrocities as the Germans, and savagely raped and pillaged its way through Prussia. It reneged on almost all its assurances to the British and Americans made at the Yalta Conference (February 4–11, 1945) to allow liberated nations of Eastern Europe to form their own autonomous governments by free elections, once it crossed into Eastern Europe. But more than any other force, it destroyed the infantrymen and armor of the Wehrmacht.26

THE RUSSIAN FRONT not only fatally weakened the German army, but also revived the moribund Western theater. England had survived the Battle of Britain, and when Hitler’s attention turned eastward, it took advantage of such a reprieve to reformulate its army, to send armies abroad, and with mixed success to attack the Axis powers where they were weakest. With the US entry into the war after Pearl Harbor, the Anglo-Americans would eventually return to France in June 1944 to fight in a way utterly different from the manner in which the French and British had fought four years earlier, ending at Dunkirk. Just as there had been two phases of Soviet retreat and advance on the Eastern Front, so too World War II would see two continental wars for Western Europe: the first ending badly in June 1940 and the second beginning well in June 1944.

In the next chapter, how the wars on the ground turned global after 1941 is explained through a variety of reasons. The Soviets in 1943 did not collapse, but retreated and regrouped in a way the Western Europeans had not in 1940. The Red Army went back on the offensive against Germany without the need of a substantial navy or vast air fleet, in a way that the armies of the Anglo-Americans, eventually to be based in Britain, could not.

A common theme developed in the various theaters in China, Burma, and the Pacific Islands, along with the fighting in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. The newfound alliance of Britain and the United States as yet lacked armies large and experienced enough to invade either the German or Japanese homeland. That fact drew their ground forces to the circumference of the Third Reich in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy, and the Pacific islands and Burma at the edges of the Japanese Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. By late 1943, the ascendant British and American armies had evolved into experienced, deadly forces, and saw their expeditionary fighting in the Mediterranean and Pacific as the necessary requisites for invading Germany and Japan in order to win the war decisively—and to win it on their terms.