Child Health Disparities

Lee M. Pachter

Health and illness are not distributed equally among all members in most societies. Differences exist in risk factors, prevalence and incidence, manifestations, severity, and outcome of health conditions, as well as in the availability and quality of healthcare. When these differences are modifiable and avoidable, they are referred to as disparities or inequities . The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Healthy People 2020 report defines health disparity as “a particular type of health difference that is closely linked with social, economic, and/or environmental disadvantage. Health disparities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group; religion; socioeconomic status; gender; age; mental health; cognitive, sensory, or physical disability; sexual orientation or gender identity; geographic location; or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.” The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) define health disparities as “preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations.” Health and healthcare disparities occur by nature of unequal distribution of resources that are inherent in societies that exhibit social stratification , which occurs in social systems that rank and categorize people into a hierarchy of unequal status and power. There exists a hierarchy of “haves and have nots” based on group classifications.

Although there are many differences regarding health status, not all these differences are considered disparities. The increased prevalence of sickle cell disease in people of African descent, or the increased prevalence of cystic fibrosis in white individuals of Northern European descent, would not be considered a disparity because—at least at present—the genetic risk is not easily modifiable. However, in 2003, funding was 8-fold greater per patient for cystic fibrosis than for sickle cell disease, which could be considered a disparity because it is modifiable.

Health and healthcare disparities have existed for centuries. A critical mass of research building in the mid-2000s corresponded to the U.S. Institute of Medicine's 2003 book, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare . It reviewed the literature on racial and ethnic disparities in health and healthcare and found 600 citations.

Determinants of Health and Health Disparities

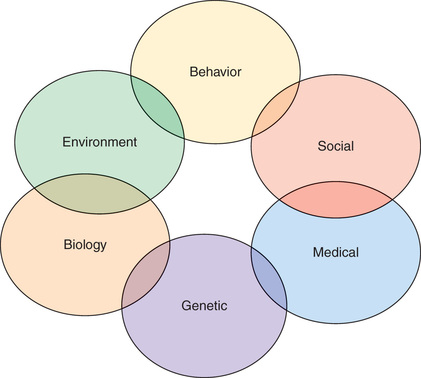

Fig. 2.1 displays a categorization of the multiple determinants of health and well-being. Applying this categorization to health disparities, conceptualizations of the root causes of health disparities emphasize the most modifiable determinants of health: the physical and social environment, psychology and health behaviors, socioeconomic position and status, and access to and quality of healthcare. Differential access to these resources result in differences in material resources (e.g., money, education, healthcare) or psychosocial factors (e.g., locus of control, adaptive or risky behaviors, stress, social connectedness) that may contribute to differences in health status.

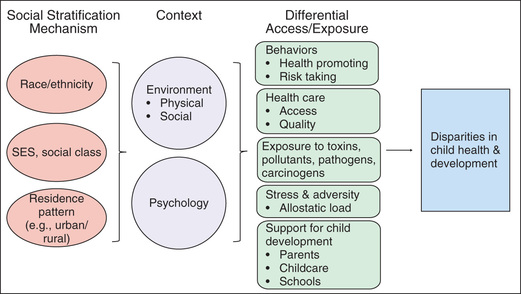

Fig. 2.2 illustrates the complex relationships among multileveled factors and health outcomes. Social stratification factors such as socioeconomic status (SES), race, and gender have profound influences on environmental resources available to individuals and groups, including neighborhood factors (e.g., safety, healthy spaces), social connectedness and support, work opportunities, and family environment. Much of the differential access to these resources results from discrimination, on a systematic or interpersonal level. Discrimination is defined as negative beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors resulting from categorizing individuals based on perceived group affiliation, such as gender (sexism) or race/ethnicity (racism).

SES, race/ethnicity, gender, and other social stratification factors also have effects on psychological functioning, including sense of control over one's life, expectations, resiliency, negative affect, and perceptions of and response to discrimination. Environmental and psychological context then have influence over more proximal determinants of health, including health-promoting or risk-promoting behaviors; access to and quality of healthcare and health education; exposure to pathogens, toxins, and carcinogens; pathophysiologic (biologic) and epigenetic response to stress; and the resources available to support optimal child development. Variability in these factors in turn results in differential health outcomes.

Psychosocial Stress and Allostatic Load

An understanding has emerged that helps explain how psychosocial stress influences disease and health outcomes (Fig. 2.3 ). This theory, allostatic load , provides insight into the processes and mechanisms that may contribute to health disparities. Allostasis refers to the normal physiologic changes that occur when individuals experience a stressful event. These internal reactions to an external stressor includes activation of the stress-response systems, such as increases in cortisol and epinephrine, changes in levels of inflammatory and immune mediators, cardiovascular reactivity, and metabolic and hormone activation. These are normal and adaptive responses to stress and result in physiologic stability in the face of an external challenge. After an acute external stress or challenge, these systems revert to normal baseline states. However, when the stressor becomes chronic and unbuffered by social supports, dysregulation of these systems may occur, resulting in pathophysiologic alterations to these responses, such as hyperactivation of the allostatic systems, or burnout. Over time this dysregulation contributes to increased risk of disease and dysfunction. This pathophysiologic response is called allostatic load .

Given the systems affected (e.g., metabolic, immune, inflammatory, cardiovascular), allostatic load may contribute to increase incidence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, asthma, and depression. It is notable that these specific chronic diseases have increased prevalence in racial and ethnic minority groups. Racial and ethnic minorities experience significantly higher degrees of chronic psychosocial stress (see Fig. 2.2 ), which over time contributes to allostatic load and the resultant disparities in these chronic diseases. Many of these conditions are noted to occur in adulthood, demonstrating the life course consequences of chronic psychosocial stress and adversity that begins in childhood.

The allostatic load model provides a pathophysiologic mechanism through which social determinants of health contribute to health disparities. It complements other mechanisms noted in Fig. 2.2 , such as differential access to healthcare, increase in health risk behaviors, and increased exposure to pathogens, toxins, and other unhealthy agents.

The Hispanic Paradox

Whereas data suggest that minority racial and ethnic groups typically have worse health outcomes than the majority white group, this is not always the case. This finding demonstrates the complex interrelationship among race/ethnicity, minority status, and other factors that contribute to disparities, such as social class and SES.

Studies suggest that for many health outcomes, Hispanic/Latino populations do significantly better than other minority racial/ethnic groups and sometimes as well as the majority non-Hispanic white population. This finding has been called the Hispanic Paradox (also known as the Latino Paradox, Epidemiologic Paradox, Immigrant Paradox, and Health Immigrant Effect). Hispanic life expectancy is about 2 yr higher than for non-Hispanic whites, and mortality rates are lower for 7 of the 10 leading causes of death. Among child health issues, Hispanics in general have lower rates of prematurity and low birthweight than African Americans, and Mexican Americans have lower rates of asthma than African Americans and non-Hispanic whites.

Several hypotheses may explain these epidemiological findings. First, the relative advantages seen in Hispanic health are greatest for non–U.S.-born Hispanics , and many of the health advantages become nonsignificant in second- or third-generation U.S. Hispanics (as individuals spend more time in the United States). Thus, indigenous cultural beliefs and lifestyles brought over by Hispanic immigrants may provide a selective health advantage, including low rates of tobacco and illicit drug use, strong family support and community ties, and healthy eating habits. Health advantages disappear as immigrants become more acculturated to U.S. standards—poorer nutritional habits and tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use—supporting this theory. It is also hypothesized that those who immigrate to the United States are younger and healthier than those Hispanics who do not immigrate and stay in their country of origin, so there may be a selection bias; Hispanic immigrants may start out healthier on arrival. Recent immigrants also tend to reside in ethnic enclaves, and socially supportive residential environments are associated with better health outcomes. When immigrants acculturate to U.S. lifestyles, not only do they acquire unhealthy behaviors, but they also tend to lose the protective aspects of their original culture and lifestyle.

There are also differences in outcomes among different Hispanic/Latino subgroups. Selective advantages in Hispanics are usually found among Hispanics from Mexico or South/Central America. Puerto Rican Hispanics typically have worse outcomes, compared to other Hispanic groups and non-Hispanic whites. Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory (Puerto Ricans are not immigrants) and has many of the negative health profiles seen in the mainland (e.g., high rates of tobacco rates and other health risk behaviors), which further supports the importance of indigenous, healthy, cultural behaviors and lifestyle as an explanation for the healthy immigrant profile seen in Central and South American Hispanics.

Disparities in Child Health and Healthcare:

Tables 2.1 and 2.2 display some of the known disparities in child health and healthcare. As previously noted, health disparities may occur as a result of race/ethnicity,socioeconomic status (often operationalized through family income, sometimes using insurance status as a proxy), and residency patterns, such as urban and rural locale.

Table 2.1

| HEALTH INDICATOR | RACE/ETHNICITY | FAMILY INCOME | RESIDENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child health status fair or poor | Black & Hispanic > White & Asian | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Children with special health care needs (CSHCN) | Black > White > Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| One or more chronic health conditions | Black > White > Hispanic > Asian | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Asthma | Mainland Puerto Rican > Black > White & Mexican American | Poor > Not Poor | Urban > Rural |

| Obesity | Hispanic & Black > White and Asian | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Infant mortality | Black > Hispanic > White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Low birthweight (<2,500 g.) |

Black > White, Hispanic, American Indian/Native Alaskan, Asian/Pacific Islander Mainland Puerto Rican > Mexican American |

Poor > Not Poor | |

| Preterm birth (<37 wk) |

Black > American Indian/Native Alaskan, Hispanic, White, Asian/Pacific Islander Mainland Puerto Rican > Mexican American |

Poor > Not Poor | |

| Seizure disorder, epilepsy | Black > White, Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Bone, joint, or muscle problem | White > Black, Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Ever breastfed | White, Hispanic, Asian > Black | Not Poor > Poor | Urban > Rural |

| No physical activity in the past week |

Hispanic > Black, Asian > White Poor > Not Poor |

Poor > Not Poor | |

| Hearing problem | Poor > Not Poor | ||

| Vision problem | Poor > Not Poor | ||

| Oral health problems (including caries and untreated caries) | Hispanic > Black > White, Asian | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | White, Black > Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Have ADHD but not taking medication | Hispanic, Black > White | ||

| Anxiety problems | White > Black, Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Depression | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban | |

| Behavior or conduct problem (ODD, conduct disorder) | Black > White, Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | White > Black > Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Learning disability | Black > White, Hispanic | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Developmental delay | Black > White > Hispanic, Asian | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Risk of developmental delay, by parental concern | Hispanic > Black & White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Speech or language problems | Poor > Not Poor | ||

| Adolescent suicide attempts (consider, attempt, needed medical attention for an attempt) |

Girls: Hispanic > Black & White Boys:Hispanic & Black > White |

||

| Adolescent suicide rate |

Girls: American Indian > White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Black Boys: American Indian & White > Hispanic, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander |

||

| Child maltreatment (reported) | Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Multiracial > White, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific islander | Poor > Not Poor | |

| AIDS (adolescents) | Black > Hispanic > White |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

Table 2.2

| HEALTHCARE INDICATOR | RACE/ETHNICITY | FAMILY INCOME | RESIDENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did not receive any type of medical care in past 12 mo | Hispanic, Black, Asian > White | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| No well-child checkup or preventive visit in past 12 mo | Hispanic > White & Black | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Delay in medical care | Hispanic > Black > White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Unmet need in healthcare due to cost | Black > Hispanic > White > Asian | Poor > Not Poor | |

| No coordinated, comprehensive, or ongoing care in a medical home | Hispanic > Black & Asian > White | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| Problem accessing specialist care when needed | Hispanic & Black > White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| No preventative dental care visit in past 12 mo | Hispanic & Asian > Black > White | Poor > Not Poor | Rural > Urban |

| No vision screening in past 2 yr | Hispanic & Asian > Black & White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Did not receive needed mental health treatment or counseling in past 12 mo | Black & Hispanic > White | Poor > Not Poor | |

| Not receiving a physician recommendation for HPV vaccination among 13-17-yr- old girls | Black & Hispanic > White | ||

| Immunization rates: adolescent HPV vaccine |

Girls: White > Black & Hispanic Boys: Black & Hispanic > White |

HPV, Human papillomavirus.

Child Health Disparities

Asthma

Disparities in asthma prevalence are seen by racial/ethnic group and SES. According to the 2015 U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), American Indian/Alaskan Native, Mainland Puerto Rican, and African American children have the highest prevalence of childhood asthma (14.4%, 13.9%, and 13.4%, respectively), followed non-Hispanic white (7.4%) and Asian (5.4%). The prevalence of childhood asthma in Hispanics is 8%, but when the Hispanic category is disaggregated, Mexican Americans have a prevalence of 7.3%, which is lower than that for non-Hispanic whites; Puerto Rican children have among the highest rates of asthma. The cause of this difference among Hispanic/Latino subgroups is debatable, but some data suggest that bronchodilator response may be different in the 2 groups, possibly based on genetic variants. Data also suggest that within the Mexican American population, differences in prevalence exist based on birthplace or generation (see earlier, The Hispanic Paradox ): immigrant and first-generation Mexican American children have lower prevalence of asthma than Mexican American children who have lived in the United States longer. This may reflect the changes that occur as Latinos become more acculturated to U.S. behavioral norms the longer they reside in the United States (e.g., tobacco use, dietary patterns, environmental exposures).

Regarding SES, children living at <100% the federal poverty level have a childhood asthma prevalence of 10.7%, whereas those living at ≥200% the poverty level have a prevalence of 7.2%.

Obesity

In 2014 the percentage of Hispanic/Latino children in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) age 6-17 yr who were obese was 24.3%. The percentage of African American children who were obese was 22.5%. This compares to non-Hispanic whites (17.1%) and Asian (9.8%) (see Fig. 2.3 ). Dietary patterns, access to nutritious foods, and differing cultural norms regarding body habitus may account for some of these differences. The relationship between SES and childhood obesity is less clear. Some studies suggest that the racial and ethnic differences in childhood obesity become nonsignificant when factoring in family income, whereas other national survey studies suggest a relationship between family income and obesity rates in non-Hispanic whites but not among black or Mexican American children.

Infant Mortality

Highest rates of infant mortality are seen in non-Hispanic black infants. According to data from the 2007–2008 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)–linked Live Birth–Infant Death Cohort Files, the odds ratio for non-Hispanic black infant mortality is 2.32, compared to non-Hispanic white rates, and remains significant after controlling for maternal age, education, marital status, parity, plurality, nativity, tobacco use, hypertension, and diabetes. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, higher infant mortality is also seen in Hispanic black and Hispanic white infants as well.

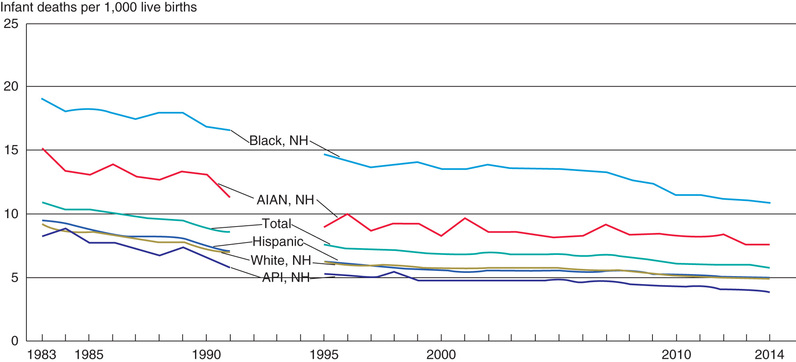

In 2012 the infant mortality rate for black, non-Hispanic (11.2/1,000 live births) and American Indian/Alaskan Native (8.4/1,000) infants was higher than for white, non-Hispanic (5.0/1,000), Hispanic (5.1/1,000), and Asian/Pacific Islander (4.1/1,000) (Fig. 2.4 ). There was variation in the U.S. Hispanic population: the Puerto Rican infant mortality rate was 6.9/1,000, compared to 5.0/1,000 for Mexican Americans and 4.1/1,000 for Central and South American origin.

Prematurity and Low Birthweight

There are significant black-white differences in preterm birth and low birthweight (LBW) (Fig. 2.5 ). According to the 2014 NCHS National Vital Statistics System, LBW births (<2500 g) were significantly higher among black non-Hispanic women (13.2%) than white non-Hispanic (7.0%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (7.6%), Asian/Pacific Islander (8.1%), or Hispanic (7.1%) women. Among Hispanics, Puerto Rican women had higher rates of LBW births than Mexican Americans (9.5% vs 6.6%).

Regarding preterm births (<37 wk), the black non-Hispanic rate was 13.2%, compared to 8.9% for white non-Hispanics, 8.5% for Asian/Pacific Islanders, 10.2% for American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 9% for Hispanics. Within the Hispanic group, the Puerto Rican preterm rate was higher than for Mexican Americans (11% vs 8.8%).

There are many hypotheses for the increased rates of preterm birth and LBW in black births. Risk factors such as inadequate prenatal care, genitourinary tract infections, increased exposure to environmental toxins, and increased tobacco use may account for some of the disparity, but not all, and neither do SES differences, since high-SES black women still have higher rates of premature and LBW births.

Increased stress has been presented as a potential mechanism. Studies have shown that minority women who experience perceptions of racism and discrimination have higher odds of delivering a preterm or LBW child than do minority women who have not perceived experiences with discrimination. Residential segregation is also a potential source of differences in preterm and LBW outcomes. Living in hypersegregated neighborhoods can decrease access to prenatal care, increased exposure to environmental pollutants, and increase psychosocial stress, all of which may contribute to increased risk.

Increased age at delivery in African American women does not lessen the risk of preterm or LBW delivery (as it does in white mothers). This has led to the theory that cumulative stress in black women, related to chronic exposure to factors such as socioeconomic deprivation and racial discrimination, leads to declining health at an earlier age compared with white women, and thus increases the risk for poor pregnancy outcomes. Called the weathering hypothesis , this has been proposed as an explanation for racial variations in pregnancy outcomes.

Oral Health

Significant differences exist in oral health status as well as preventive oral healthcare according to race/ethnicity, SES, and residency locale. Data from the 1994–2004 NHANES show that compared to non-Hispanic white children, black and Mexican American children had higher rates of caries and untreated caries and lower rates of receiving dental sealants. Children living at or below the federal poverty level also had higher rates of caries and untreated caries and lower rates of dental sealant applications, compared with nonpoor children.

Preventive oral healthcare may improve rates of caries and treat caries before further impairment ensues. Data from the 2004 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey revealed that only 34.1% of black and 32.9% of Hispanic children had a yearly visit to a dentist, compared to 52.5% of white children. Likewise, only 33.9% of low-income children had dentist visits, compared to 46.5% of middle-income children and 61.8% of high-income children.

According to the 2011/12 National Survey of Children's Health (NSCH) , parents reported fair to poor teeth condition at a higher rate in Asian non-Hispanic children (8.5%), black non-Hispanic children (7.6%), and Hispanic children (15.2%), compared to white children (4.2%). Hispanic and black non-Hispanic children had higher rates of oral health problems than white non-Hispanic and Asian non-Hispanic children as well.

Hearing Care

No data suggest that the prevalence of hearing loss (either congenital or acquired) is different among racial/ethnic or SES categories, but follow-up care after diagnosis of a hearing problem has been shown to be worse in certain groups. Higher “lost to follow-up” rates have been noted in children living in rural areas as well as with publically insured and nonwhite children. Much of this disparity is reduced when families have access to specialists.

Vision Problems

The parent-reported 2011/12 NSCH found no differences in the prevalence of correctable vision problem among white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and “other” racial/ethnic groups, or with regard to SES or urban/rural residence.

Immunization

Immunization against infectious agents was one of the major clinical and public health successes of the 20th century. Rates of life-threatening infectious diseases plummet after effective vaccines are introduced. The primary series of childhood immunizations against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, rotavirus, measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis A and B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, varicella, and Streptococcus pneumoniae have significantly decreased the incidence of illness caused by these agents.

Disparities in immunization rates had been noted regarding household income status, insurance status, and residential location. In response to these socioeconomic disparities, as well as higher rates of measles cases in the 1980s among racial and ethnic minority groups, a number of interventions were initiated, including the creation of the Vaccines for Children program (VFC), which eliminated the financial barrier to immunization by providing free immunizations to at-risk groups (Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, American Indian/Alaskan Native, or underinsured and vaccinated at a federally qualified health center or rural health clinic). Since VFC inception, disparities in immunization rates have either been eliminated or have significantly narrowed, showing that targeted public health programs can successfully eliminate health disparities.

Although rates of initial primary vaccine series demonstrate no or decreasing disparities, other vaccination rates do show differences. For example, black and Hispanic adolescent females have lower human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination rates than whites. Reasons for this disparity include parental concerns about safety and no provider recommendation. Of interest, studies of HPV vaccination in adolescent males show that black and Hispanic male adolescents have higher rates of HPV vaccine coverage than whites.

Adolescent Suicide

In 2014 the highest rate of suicide for male adolescents was seen in American Indian (20 per 100,000 population) and white (17/100,000) teens, compared to Hispanic (9/100,000), black (7/100,000), and Asian/Pacific Islander (6/100,000) teens. For female adolescents, highest suicide rates were seen in American Indian (12/100,000), compared to white (5/100,000), Asian/Pacific Islander (5/100,000), Hispanic (3/100,000), and Black (2/100,000) teens.

Hispanic female students in grades 9-12 were more likely to consider suicide (26%), report attempting suicide (15%), and require medical attention for a suicide attempt (5%), compared to black (19%, 10%, 4%) or White (23%, 10%, 3%) female students. Among male students, Hispanic and black students, compared to white students, were more likely to attempt suicide (8% and 7% vs 4%, respectively) and require medical attention for a suicide attempt (4% and 3% vs 1%).

Child Maltreatment

In 2014, reports of child abuse and neglect were higher in black (15.3 per 1,000 children), American Indian/Alaskan Native (13.4/1,000), and multiracial (10.6/1,000) children, compared to Hispanic (8.8/1,000), Pacific Islander (8.6/1,000), white (8.4/1,000), and Asian (1.7/1,000) children. Poverty , measured at the family as well as community level, is also a significant risk factor for maltreatment. Counties with high poverty concentration had >3 times the rate of child abuse deaths than counties with the lowest concentration of poverty. Nonetheless, race itself should not be a marker for child abuse or neglect.

Behavioral Health Disparities

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

White and black children are more often diagnosed with ADHD (10.7% and 8.4%, respectively) than are Hispanic children (6.3%), according to NHIS data. Other studies have shown that both black and Hispanic children have lower odds of having an ADHD diagnosis than white children. Children reared in homes that are below the federal poverty level are diagnosed more often (11.6%) that those at or above the FPL (8.1%).

Children diagnosed with ADHD have different medication practices. Hispanic (43.8%) and black (40.9%) children with ADHD are more likely than white children (25.5%) not to be taking medication. The causes of this disparity are unknown but may include different patient and parental beliefs and perceptions about medication side effects and different prescribing patterns by clinicians.

Depression and Anxiety Disorders

According to the 2011/12 NSCH, there were no parent-reported differences in rates of childhood depression (2-17 yr) among racial/ethnic groups. Children living in poverty, as well as children living in rural areas, had higher rates of parent-reported depression. According to the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of adolescent in grades 9-12, Hispanic students had higher rates of reporting that they felt sad or hopeless (35.3%) compared to white (28.6%) and black (25.2%) students. This relationship existed for both male and female students.

The NSCH data noted that white children ages 2-17 yr had higher rates of anxiety than black or Hispanic children. “Poor” children had higher rates of anxiety than “not poor” children.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Compared with white children, black and Hispanic children are less likely to be diagnosed with ASD, and when diagnosed, are typically diagnosed at a later age and with more severe symptoms. This disparity in diagnosis and timing of diagnosis is concerning given that early diagnosis provides access to therapeutic services that are best initiated as early as possible. Reasons for these disparities may include differences in cultural behavioral norms, stigma, differences in parental knowledge of typical and atypical child development, poorer access to quality healthcare and screening services, differences in the quality of provider–patient communication, trust in providers, as well as differential access to specialists.

Behavioral or Conduct Problems

According to the 2011/12 NSCH, black children age 2-17 yr have higher rates of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or conduct disorder than white and Hispanic children. Children living in poverty have higher rates than those not living in poverty.

Developmental Delay

The 2011/12 NSCH found that black and white children age 2-17 yr had higher rates of developmental delay than Hispanic children (4.5% and 3.8% vs 2.7%, respectively). However, when parents of children age 4 mo to 5 yr were asked if they had concerns about their child's development (highly correlated with risk of developmental, behavioral, or social delays), Hispanic children had higher rates of moderate or high risk for developmental delay (32.5%) than did black (29.7%) or white (21.2%) children. This discrepancy may result from either overestimation of concerns in Hispanic mothers or underdiagnosis of Hispanic children by clinicians.

Children living below the poverty level have higher rates of developmental delay as well.

Disparities in Healthcare

In almost all areas, minority children have been identified as having worse access to needed healthcare, including receipt of any type of medical care within the past 12 mo, well-child or preventive visits, delay in care, having an unmet need due to healthcare cost, lack of care in a medical home, problems accessing specialist care when needed, lack of preventive dental care, vision screening, mental health counseling, and recommendations for adolescent immunizations (see Table 2.2 ). In addition, many of these healthcare indicators are found to be worse for children living in poverty, as well as those living in a rural area, compared to urban-dwelling children.

Approaches to Eradicating Disparities: Interventions

Much of the information regarding health disparities over the past 10-20 yr has focused on the identification of areas where health disparities exist. Additional work has expanded on simple description and acknowledged the multivariable nature of disparities. This has provided a more nuanced understanding of the complex interrelationships among factors such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, social class, generation, acculturation, gender, and residency.

An example of a successful intervention that closed the disparity gap is the implementation of the VFC program, which, as noted earlier, significantly decreased the disparity in underimmunization rates noted among racial/ethnic groups and poor/underinsured children. This is an example of a public health policy approach to intervention.

Interventions need to occur at the clinical level as well. The almost universal use of electronic health records (EHR) provides a unique opportunity for collecting clinical and demographic data that can be helpful in identify disparities and monitor the success of interventions. All EHR platforms should use a standardized approach to gathering information on patient race/ethnicity, SES, primary language preferences, and health literacy. The Institute of Medicine's 2009 report Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement provides best practices information about capturing these data in the health record.

The advancing science of clinical quality improvement can also provide a framework for identifying clinical strategies to reduce disparities in care. Use of PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) cycles targeting specific clinical issues where health disparities exist can result in practice transformation and help reduce differential outcomes.

Another practice-level intervention that has the potential to reduce disparities in care and outcomes is the medical home model, providing care that is accessible, family centered, continuous, comprehensive, compassionate, coordinated, and culturally effective. The use of care coordinators and community-based health navigators is an effective tool in helping to break down the multiple social and health system barriers that contribute to disparities.

Population health strategies have the advantage of addressing the determinants of disparities at both the clinic and the community levels. Techniques such as “hotspotting,” “cold-casing” (finding patients and families lost to follow up and not receiving care), and “geocoding,” combined with periodic community health needs assessments, identify the structural, systemic, environmental, and social factors that contribute to disparities and help guide interventions that are tailored to the local setting.

When developing strategies to address disparities, it is imperative to include patients and community members from the beginning of any process aimed at identification and intervention. Many potential interventions seem appropriate and demonstrate efficacy under ideal circumstances. However, if the intervention does not address the concerns of the end users—patients and communities—or fit the social or cultural context, it will likely be ineffective in the “real world.” Only by involving the community from the beginning, including defining the issues and problems, can the likelihood of success be optimized.

Health disparities are a consequence of the social stratification mechanisms inherent in many modern societies. Health disparities mirror other societal disparities in education, employment opportunities, and living conditions. While society grapples with the broader issues contributing to disparities, healthcare and public health can work to understand the multiple causes of these disparities and develop interventions that address the structural, clinical, and social root causes of these inequities.

Racism and Child Health

Mary T. Bassett, Zinzi D. Bailey, Aletha Maybank

Keywords

- adverse childhood experiences

- cultural humility

- cultural safety

- doll experiment

- equity

- implicit bias

- infant mortality rate

- institutional racism

- internalized racism

- interpersonal racism

- microaggression

- racial disparities

- residential segregation

- social determinants

- stereotype threat

- structural competency

- structural racism

Racism as Social Determinant

An emerging body of evidence supports the role of racism in a range of adverse physical, behavioral, developmental, and mental health outcomes. Racial/ethnic patterning of health in the United States is long-standing, apparent from the first collection of vital statistics in the colonial period. However, the extensive data that document racial disparities have not settled the question of why groups of people, particularly of African and Native American Indian ancestry, face increased odds of shorter lives and poorer health (Table 2.3 ). The role of societal factors, not only factors related to the individual, is increasingly recognized in determining population health, but often omits racism among social determinants of health. This oversight occurs in the face of a long history of racial and ethnic subjugation in the United States that has been justified both explicitly and implicitly by racism. From the early 18th century, colonial America established racial categories that enshrined the superiority of whites, conferring rights specifically on white men, while denying these rights to others. Similar, perhaps less explicit, discrimination has continued through the centuries and remains a primary contributor to racial inequities in children's health.

Table 2.3

New Social and Health Inequities in the United States

| TOTAL | WHITE NON-HISPANIC | ASIAN* | HISPANIC OR LATINO | BLACK NON-HISPANIC † | NATIVE AMERICAN OR ALASKA NATIVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth: median household assets (2011) | $68,828 | $110,500 | $89,339 | $7,683 | $6,314 | NR |

| Poverty: proportion living below poverty level, all ages (2014); children <18 yr (2014) | 14.8%; 21.0% | 10.1%; 12.0% | 12.0%; 12.0% | 23.6%; 32.0% | 26.2%; 38.0% | 28.3%; 35.0% |

| Unemployment rate (2014) | 6.2% | 5.3% | 5.0% | 7.4% | 11.3% | 11.3% |

| Incarceration: male inmates per 100,000 (2008) | 982 | 610 | 185 | 836 | 3,611 | 1,573 |

| Proportion with no health insurance, age <65 yr (2014) | 13.3% | 13.3% | 10.8% | 25.5% | 13.7% | 28.3% |

| Infant mortality per 1000 live births (2013) | 6.0 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 10.8 | 7.6 |

| Self-assessed health status (age-adjusted): proportion with fair or poor health (2014) | 8.9% | 8.3% | 7.3% | 12.2% | 13.6% | 14.1% |

| Potential life lost: person-years per 100,000 before age 75 yr (2014) | 6621.1 | 6659.4 | 2954.4 | 4676.8 | 9490.6 | 6954.0 |

| Proportion reporting serious psychological distress ‡ in past 30 days, age ≥18 yr, age-adjusted (2013–14) | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 4.5% | 5.4% |

| Life expectancy at birth (2014), yr | 78.8 | 79.0 | NR | 81.8 | 75.6 | NR |

| Diabetes-related mortality: age-adjusted mortality per 100,000 (2014) | 20.9 | 19.3 | 15.0 | 25.1 | 37.3 | 31.3 |

| Mortality related to heart disease: age-adjusted mortality per 100,000 (2014) | 167.0 | 165.9 | 86.1 | 116.0 | 206.3 | 119.1 |

* Economic data and data on self-reported health and psychological distress are for Asians only; all other health data reported combine Asians and Pacific Islanders.

† Wealth, poverty, and potential life lost before age 75 yr are reported for the black population only; all other data are for the black non-Hispanic population.

‡ Serious psychological distress in the past 30 days among adults 18 yr and older is measured using the Kessler 6 scale (range: 0–24; serious psychological distress ≥13).

NR, Not reported.

Wealth data from the US Census; poverty data for adults from National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and poverty data for children from National Center for Education Statistics; unemployment data from US Bureau of Labor Statistics; incarceration data from Kaiser Family Foundation; data on uninsured individuals from NCHS; data on infant mortality, self-assessed health status, potential life lost, serious psychological distress, life expectancy, diabetes-related mortality, and mortality related to heart disease from NCHS.

From Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al: Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions, Lancet 389:1453–463, 2017 (Table, p 1455).

For generations, racial/ethnic disparities have been documented beginning at birth and extending across life. In 2014, life expectancy at birth for blacks was almost 4 yr shorter than life expectancy of non-Hispanic whites, influenced heavily by disparities starting at birth (Table 2.3 ). The infant mortality rate (IMR), arguably the most important measure of national health, has shown a persistent relative black-white gap. Despite the substantial decline in U.S. IMR for all racial/ethnic groups, there is still at least a 2-fold higher risk of death in the 1st yr of life for black infants than for white infants (Table 2.3 ). NCHS data in 2014 showed a double-digit IMR only among non-Hispanic blacks, with 11.8 deaths per 1,000 live births, compared to 4.89/1,000 for non-Hispanic whites. In 2016 the black IMR slightly increased after many years of progressive decline, which may portend a further rise in the relative black-white gap. A troubling stagnation in IMR, with no recent decline, is found among Alaska Natives and American Indians. The 2005 IMR in American Indian or Alaskan Native women, 8.06 deaths/1000 live births, has remained essentially unchanged for a decade, with the 2014 IMR at 7.59/1,000.

Exposures that affect infant survival occur before birth. Prenatal maternal exposures to pesticides, lead, and other environmental toxins vary by race. Additionally, a higher prevalence of maternal obesity, diabetes, and substance/alcohol use before conception also adversely affects birth outcomes. A California study of maternal obesity based on claims data and vital records found that 22.3% of pregnant black women and 20.3% of Latina women had a body mass index (BMI) of 30-40, compared to 14.9% of white and 5.6% of Asian women. BMI >40 was more than twice as prevalent in black (5.7%) than white (2.6%) women.

The effects of racism are also stressful and toxic to the body, and evidence supports biologic effects of discrimination across the life span, especially for pregnant women. Racism can increase cortisol levels and lead to a cascade of effects, including impaired cell function, altered fat metabolism, increased blood glucose and blood pressure, and decreased bone formation (see Chapter 1 , Fig. 1.3 ). This can affect a growing fetus, leading to increased infant cortisol levels, lower birthweight (LBW), and prematurity. In New York City, white women had lower rates of adverse birth outcomes: 1.3% had preeclampsia, less than half the rate for black women (2.9%).

Although infant deaths occur more frequently among low-income groups of all race/ethnicities, these birth outcome disparities by race/ethnicity are found also in blacks with higher socioeconomic status (SES). College-educated black women are more likely than white high school–educated women to have a LBW infant, a principal risk factor for infant death. Another study examined California birth certificates of pregnant Arab American women after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and found that those who experienced discrimination immediately after the 9/11 attacks had a higher relative risk of giving birth to an LBW infant in the following 6 mo than seen in births before this date.

The increased risk for populations of color continues from infancy into childhood; racial/ethnic disparities are seen across almost all health indicators, with most relative gaps remaining stagnant or worsening over the last 2 decades. Black children are about twice as likely to be diagnosed with asthma , more likely to be hospitalized for its treatment, and more likely to have fatal attacks. The black-white disparity in asthma has grown steadily over time. Native American children and youth (≤19 yr) also experience negative health outcomes, with the highest rates of unintentional injury and mortality rates at least twice as high as for other racial/ethnic groups. Additionally, according to a 2015 NCHS brief, Latino youth age 2-19 have the highest rates of obesity , defined as a BMI ≥95th percentile in the 2000 CDC sex/age-specific growth charts. The NCHS data show that 21.9% of Latino (followed by black) children qualified as obese from 2011 to 2014. Black children are more likely to be exposed to witnessed, personal, or family violence and have several-fold higher prevalence of psychiatric distress than their white counterparts, a racial difference that continues into adulthood.

Explaining Racial Disparities: A Taxonomy of Racism

Explanations of these ubiquitous racial gaps have focused on individual factors, including variation in individual genetic constitution, behavioral risks, poverty, and access to (and use of) healthcare services. Scientists agree that “race” is a social construct that is not based on biology, despite the persistence of the idea that racial categories reflect a racially distinctive genetic makeup that has a bearing on health. In fact, the genetic variation between individuals within a particular racial/ethnic group is far greater than the variability between “races.” Despite the genetic data, many groups have been “racialized” over time. Notably, the U.S. Census Bureau's demographic classifications reflect this process. In the mid-late 1800s the census counted “mulattos,” those of white and black ancestry, as another race.

Starting in the late 19th century, Eastern European immigrants and Jews were considered different races. As early as 1961, the U.S. Census identified Mexicans and Puerto Ricans as “white,” even as racial classification varied by geography. All states collected birth records by 1919, but there was little uniformity on how race was collected, if at all, across states. It was not until 1989, when the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) recommended assigning “infant race” as that of the mother, that standard guidance and categories were issued for states on collecting racial data at birth. Existing categories were changed and continue to change based on the economic, cultural, or political utility of the time, rather than actual genetic distinction.

Defining Racism

Racism has consistently structured U.S. society and is based on “white supremacy,” a hierarchical idea that whites, the dominant group, are intrinsically superior to other groups who are not classified as “white.” No single definition of racism exists, but one useful description is racial prejudice backed by power and resources . This conceptualization asserts that not only must there be prejudice, but also an interlocking system of institutions to produce and reproduce inequities in access to and utilization of resources and decision-making power. Even when considering variations in health behavior, lifestyles, economic status, and healthcare utilization, individual-level behavioral factors do not capture how broader shared social experiences shape outcomes. Racial domination or racism contributes to variation in the population's access to resources and exposure to disease, as well as the group experience of fair treatment and opportunity. Although many groups in the United States may encounter discrimination based on race/ethnicity, most of the modest literature on health effects of racism has focused on people of African descent, leaving a need to better understand the impact of racism on other nonwhite groups. Table 2.4 describes various pathways through which racism affects health.

While the empirical data on disparities for nonblack populations of color deserve greater research, useful frameworks exist to understand the disparities that public health has documented to date. A useful taxonomy of how racism operates in society has 4 categories: internalized racism, interpersonal racism, institutional racism, and structural racism. Each is relevant in considering the impact of racism on child health.

Internalized Racism

When the larger society characterizes marginalized racialized groups as “inferior,” these negative assessments may be accepted by members of those groups themselves, either consciously or unconsciously. The result is devaluation of personal abilities and intrinsic worth, as well as the capacity, of others also classified as being a part of a marginalized racialized group. The best-known documentation of internalized racism comes from the study of Kenneth and Mamie Clark known as the doll experiment , conducted in the 1940s. Black children, both boys and girls, were asked to choose between a black doll and a white doll according to attributes described by the interviewer. In response to positive attributes (e.g., pretty, good, smart ), most children chose the white doll. The Clarks interpreted this finding to mean that black children had internalized the societal views of black inferiority and white superiority, even at the expense of their personal self-image. Repeated by a New York City high school student several decades later, the findings were much the same, with 15 of 21 children endorsing positive attributes to light-skinned dolls. Multiple studies confirm that racial identity is established in young children, both black and white, along with negative views of blackness. Developmentally, however, nonwhite youth often explore racial identity earlier than their white counterparts. In terms of health outcomes, depending on perceived inferiority or superiority of the group, racial identification is associated with self-esteem, mastery, and depressive symptoms. Low self-esteem is independently implicated in mental health disorders and may contribute to the phenomenon of stereotype threat , in which personal expectation of underperformance correlates with prevailing social stereotypes and adversely affects actual performance.

Interpersonal Racism

How racial beliefs affect interactions between individuals has been the most studied aspect of racism. Interpersonal racism refers to situations where one person from society's privileged racial group acts in a discriminatory manner that adversely affects another person or group of people. Such actions may be based on explicit beliefs or on implicit beliefs of which the perpetrating individual is not consciously aware. A burgeoning field is examining how experience of unfair treatment has biologic consequences, reflected in measurable increases in stress responses.

Such effects of interpersonal racism are best documented for mental health , where perceived unfair treatment serves as psychosocial stressors, and are weaker for physical health outcomes. A 2009 study of 5,147 5th-grade students found that compared to only 7% of whites who reported experiencing racial discrimination, 15% of Latinos and 20% of blacks self-reported enduring racial discrimination. Furthermore, discriminatory experiences have been strongly and consistently linked to greater risk for anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, psychological distress, ADHD, ODD, self-esteem, self-worth, and psychological adaptation and adjustment. Perceived racial discrimination can affect behavioral, mental, and physical health outcomes and is associated with: increased alcohol and drug use among Native Americans (age 9-16 yr), increased tobacco smoking for black youth (11-19 yr), higher depressive symptoms among Puerto Rican children, and insulin resistance among young females.

Understanding the enduring impact of childhood experience on adult health has increased with the study of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (see Chapter 1 ). ACEs have well-documented cumulative negative health effects that occur across the life span and are patterned by race/ethnicity. Early experience of racism is a proxy measure for toxic stress . The question, “Was [child's name] ever treated or judged unfairly because of [his/her] race or ethnic group?” is included in the U.S. Census Bureau's National Survey of Children's Health, a random sample of 91,000-102,000 households (depending on the year) to assess the health of children up to 17 yr old. Children of color from low-income households, especially Latino children, were reported to have the lowest level of health. However, exposure to racism among higher SES did not protect children from experiencing relatively poorer health. Children exposed to racism were also more likely (by 3.2%) to have a diagnosis of ADHD. Children exposed to racism were 2 times more likely to experience anxiety and depression.

Toxic stress increases cortisol levels in the body, increasing the risk of chronic disease. A 2010 study revealed that Mexican adolescents who perceived racism experienced greater cortisol output, after controlling for other stressors. Adolescents who experience racism with no support have been shown to have higher levels of blood pressure and obesity than those with emotional support, which can be protective.

Medical practice has not been exempt from these occurrences of interpersonal racism. Using variation in adherence to established clinical standards in diagnostic and treatment decisions across racialized groups, researchers have been assessing interpersonal racism in physician–patient interactions. The most comprehensive review of such bias in clinical care remains the 2003 study by the U.S. Institute of Medicine, in which the discriminatory treatment was inferred from examination of clinical decision-making rather than from directly observed interactions. For virtually every condition studied, black patients were less likely to receive recommended care. Such racial bias has been most extensively established in adults but also extends to children. A study conducted in an emergency department found pediatric patients (<21 yr) were less likely to receive medically indicated pain medication if they were black, mirroring the historical misconception of reduced pain sensitivity among blacks. Within this context, it is unsurprising that perceived interpersonal racism has been linked to healthcare utilization, including delays in seeking care or filling prescriptions and distrust of the health system.

Institutional Racism

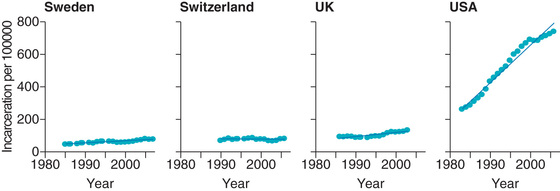

Interpersonal racism clearly inflicts harms, but even if completely eliminated, racial inequities would persist because of institutional and structural racism. Broadly, institutional racism refers to patterns of discrimination based on policy, culture, or practice and carried out by state and nonstate institutions (e.g., corporations, universities, legal systems, cultural institutions) within various sectors (e.g., housing, education, criminal justice). Key to current residential segregation are banking practices dating to the post-Depression era. As an institution, the education system has been another tragic case of how racism impacts children's health. In addition, mass incarceration by the criminal justice system has dramatically increased in the United States while remaining relatively flat in other developed countries (Fig. 2.6 ). Over a lifetime, approximately 30% of African American men have been imprisoned.

In school, children of color can experience not only individual racism but also institutional racism, as documented by higher rates of disciplinary actions such as suspensions, and at younger ages than white children. According to a 2016 U.S. Department of Education civil rights survey, black children, who represent only 19% of national preschool students, account for a staggering 47% of at least 1 out-of-school suspension. Black preschoolers are 3.6 times more likely to be suspended than their white peers. Black females, representing 20% of female preschool population, account for 54% of out-of-school suspensions.

Unfortunately, this disparity persists as children continue through the school system: for kindergarten to grade 12 (K-12) students, black children are 3.8 times more likely to face out-of-school suspension than white peers. This inequity is particularly harmful because the educational system feeds into the criminal justice system. Black students are 2.2 times more likely to have either school-related arrests or law enforcement referrals than their white peers. The U.S. Department of Education survey also reveals racial inequities among children with disabilities. For K-12 children with disabilities covered under the Individuals with Disability in Education Act, 21% of multiracial females were issued with at least 1 out-of-school suspension, compared to 5% of white females.

In addition to the threat to educational and employment prospects, school suspensions also risk children's health. A 2016 brief from the Yale Child Study Center states that early suspensions and expulsions of children harm behavioral and social-emotional development, weakening a child's overall development. Furthermore, these forms of punishment may prevent the treatment of underlying health issues, such as mental health issues or disabilities, and cause increased stress for the entire family.

Institutional racism can function without apparent individual involvement and has powerful repercussions that persist centuries later. Both medical professional organizations and educational institutions have legacies of racial discrimination rooted in scientific racism. In 2008 the American Medical Association (AMA) issued a formal apology for its long history, dating to the 1870s, of endorsing explicitly racist practices, including exclusion of black physicians, silence on civil rights, and refusal to make any public statement on federally sponsored hospital segregation. Despite a focus on medical school desegregation in the 1960s and 1970s, the presence of black students in medical schools is actually declining. Low enrollment has become especially critical for black men, who in 2014 accounted for about 500 of the 20,000 medical students nationwide. If physicians hold stereotyped views about race that affect their clinical decision-making, the declining diversity of medical student bodies may well have consequences for the quality of medical care. This history of institutional racism on people of color contributes to the mistrust, apprehension, and fear projected toward the entire medical establishment.

Structural Racism

The institutional racism within medical institutions reinforces institutional racism in other sectors, creating a larger system of discrimination, structural racism . Structural racism can be described as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination via mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, healthcare, and criminal justice. These patterns and practices in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources, which together affect risk of adverse health outcomes.” Institutional racism and structural racism are sometimes used interchangeably, but structural racism refers to overarching patterns beyond a single or even collection of institutions. Historically, government policies and practices have been largely responsible for the creation of these structures.

De facto and de jure urban residential segregation serves as a case study for how the mechanisms of structural racism operate across multiple sectors and can impact child health and development across the life course. In the 20th century, urban residential racial segregation was reinforced by the government-sanctioned policy and practice of redlining . This now-illegal practice was initiated by the U.S. Federal Housing Administration in 1934. Surveyors literally demarcated city maps with red ink to indicate those urban neighborhoods to be made ineligible for home loans. Racial composition was the most important driver of this categorization, and thus black neighborhoods were excluded from the federally financed, post-Depression home ownership boom and remained segregated. Through this segregation, existing resources were systematically removed (disinvestment ) and led to further impoverished communities of color.

The effects of residential segregation were not restricted to the banking or housing sectors. Residential segregation ties together multiple systems, driving children's access to and quality of healthcare, education, and justice, as follows

- ◆ Residential segregation and the healthcare system. Healthcare institutions were explicitly racially segregated by law and inequitably resourced until passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Vestiges of this segregation continue in recent hospital-level segregation and racial composition by hospital. In addition, institutions that provide mainly for uninsured or underserved residents are often financially unstable, leading to higher risk of closure in disinvested neighborhoods of color. On the provider level, fewer primary care and specialty physicians practice in disinvested, segregated neighborhoods, and those who are present are less likely to participate in Medicaid.

- ◆ Residential segregation and the education system. Schools have a similar history of racial segregation and, after a brief respite of integration peaking in 1980, the rates of segregation now resemble pre–Civil Rights levels of segregation. School segregation is related to high-risk health behaviors. Within these schools and in their neighborhoods, black children experience disproportionate penalization and criminalization in the educational and criminal justice systems, reinforcing institutional racism in other sectors and other forms of racism. A low-income black child is much more likely than a low-income white child to live in a segregated neighborhood. The result is that the black child will face not only the cumulative disadvantage in both family and neighborhood resources and experiences over time, but also the initiation of chains of disadvantage during sensitive periods of childhood key for development and adult transition (e.g., early childhood, adolescence).

- ◆ Residential segregation and the criminal justice system. Incarceration is concentrated in overpoliced and criminalized black communities. In the NCHS, almost 13% of black children had a parent imprisoned during their childhood (to age 17 yr), compared to about 6% of white children. Parental incarceration, which may start with a traumatic arrest in the home and later disrupt caregiving, create social stigma, deepen financial disadvantage, disconnect parents emotionally from children, and disrupt children's psychological development, has been independently associated with higher risk of children's antisocial behavior.

Most notably, experiences directly related to institutional and structural racism, operating through residential segregation (including financial hardship, parental imprisonment, and neighborhood violence), result in higher levels of ACEs for blacks and Latinos than whites. There has been growing, consistent evidence of the lifelong association between ACEs and a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes across the life course.

Structural racism, shown here with the example of residential segregation, affects child health through various direct and indirect, overlapping pathways, including the concentration of dilapidated housing, inferior quality of the social and built environment, exposure to pollutants and toxins, limited access to high-quality primary and secondary education, few well-paying jobs, overpolicing and criminalization, adverse experiences, and limited access to quality healthcare.

Opportunities to Address Racism

Racism as a determinant of health has strong empirical support, and there is promising evidence for community-wide approaches to its mitigation. Less is known about effective interventions in clinical settings. Most medical schools and subsequent training will not have prepared practitioners to examine the role of racism in their patients’ lives or clinical care settings. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to expect that pediatricians can help address racism and promote racial justice in at least 3 ways: during individual patient encounters and at their practice sites, as members of institutions that provide medical care and training, and as respected community members.

Clinical Settings

A first step is understanding that racism affects everyone and personally assessing implicit bias . Such biases reflect reflexive patterns of thinking often using racial stereotypes stemming from living in a racially stratified society. The Project Implicit Race Implicit Association Test (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html ) is available online, and its results are confidential. The purpose of such tests is to create awareness, not apportion blame. Nonetheless, results are usually jarring for all participants, no matter their racial identity, many of whom will uncover negative racial biases of which they were unaware. Such individual assessments may contribute to addressing interpersonal racism as it triggers self-reflection. Further, a growing number of organizations offer training in understanding common behaviors associated with implicit bias, including microaggressions (see later) and inequitable hiring practices. Recognizing and undoing personal biases as pediatricians requires training to challenge existing thought processes and actions that are often difficult to see.

Pediatricians and other health workers have an entrusted role in families that requires a partnership. Recognizing the strengths of families and valuing their lived experiences of internalized and interpersonal racism as expertise fosters a more collaborative clinical interaction and relationship. This expertise cannot be readily captured by pedagogy or acquired by a pediatrician in training or clinical practice. Such an approach emphasizes respect for the expertise that caregivers bring to raising their child and begins with the presumption that caregivers want to do what is best for the child. By doing this, physicians can form a collaborative relationship, rather than one based on racial stereotypes and blame. Cultural competence is a widespread concept recognizing that other cultures exist that the dominant culture must learn to decode. In contrast, the concept of cultural humility , for which training is increasingly available, considers equality among cultures and a partnership approach to differences.

During clinical encounters with children and families, healthcare workers can use their authority to acknowledge racism. Pediatricians should broach “The Talk” with their patients who are black, young adolescent, and male. “The Talk” is the conversation that black parents typically initiate with their sons regarding interactions with police. In doing so, the pediatrician affirms the need for such conversations to promote safety and may provide opportunities to connect families to community resources. For all young children and youth of color, pediatricians should ask patients if they have they been treated unfairly because of their race, recognizing this can by a form of bullying . The experience of racism at all levels can be traumatic. Trauma consists of experiences or situations that are emotionally painful and distressing, and that overwhelm people's ability to cope, leaving them powerless. Pediatricians must consider adopting trauma-informed care practices that shift the paradigm from, “What is wrong with you?” to, “What has happened to you?”

In addition, healthcare providers must strive for structural competency , which is the “trained ability to discern how a host of issues defined clinically as symptoms, attitudes, or diseases also represent the downstream implications of a number of upstream decisions,” according to Johnathan M. Metzl and Helena Hansen. Consequently, it is helpful to ensure that clinical practices are aware of other social services that may enhance health and engagement with clinical care, such as need for legal counsel to address substandard housing, counter landlord harassment, or negotiate threatened evictions (http://medical-legalpartnership.org/ ), or the support of literacy by prescribing or distributing children's books in order to encourage parents to read to children (http://www.reachoutandread.org/ ).

Institutional Settings

The healthcare institution more broadly is also a setting where racial dynamics occur. Introducing conversations about race may uncover experiences that would not otherwise be apparent. A common outcome of implicit racial bias is microaggressions , actions and attitudes that may seem trivial or unimportant to the perpetrators but create a cumulative burden for those who perceive them. A physician of color might be asked for identification on entering a hospital, while white colleagues are not so queried. These microaggressions occur in interactions among staff as well with patients and may contribute to an unspoken and uncomfortable racial climate. While such interactions rarely would violate federal discrimination standards, interaction between co-workers shapes an entire practice and can be perceived by families.

Encouraging institutions to assess the impact of race among patients and staff is a first step. Healthcare delivery institutional settings can use both data and patient accounts to examine racial effects in the practice and experience by routinely disaggregating assessment measures by race/ethnicity. Patient-reported satisfaction or quality of care might be disaggregated by race. In addition, it is important to consider racial equity within the practice's employment structure: Are there discrepancies in hiring, retention, and salaries by race? Are there proper supervision and grievance procedures, particularly around issues related to racial microaggressions? Also, consider the images and language used to discuss and represent both patients and staff, particularly when alluding to race/ethnicity. Organizations such as Race Forward (https://www.raceforward.org ) and organizational assessment tools developed by the Race Matters Institute can help to guide institutional assessments and internal change processes. Several local health departments have already incorporated antiracism training into staff professional development and introduced internal reforms to drive organizational change. Since institutional reform is closely associated with other models of productive practices, including quality improvement, collective impact, community engagement, and community mobilization, application of an antiracism lens should be judged by its contributions to organizational effectiveness as well as on its moral merits.

Education or training institutions have a special role in ensuring a workforce that is both diverse and informed. Patterns of student admissions should be scrutinized, as should the curriculum. Although many medical schools now include diversity training and provide instruction on cultural competency, such instruction is often brief (and sometimes delivered online). By contrast, approaches based on structural competency, cultural humility, and cultural safety have been implemented in health professionals’ training in such countries as Canada and New Zealand. These approaches emphasize the value of gaining knowledge about structural racism, internalized scripts of racial superiority and inferiority, and the cultural and power contexts of health professionals and their patients or clients. Health professionals benefit from the scholarship of diverse disciplines about the origins and perpetuation of, as well as remedies to counter, racism. Finding class time for these topics encounters a biomedical bias that is widespread in medical education, although arguably successful medical practice also requires a host of skills in addition a firm grounding in pathophysiology and recommended treatments. Racism results in damaging disparities that cause ill health and shorten lives, which justifies the teaching hours committed to its understanding.

Pediatricians as Advocates for Antiracist Practices and Systems

Physicians are respected members of communities and wield the power, privilege, and responsibility for dismantling structural racism. A conceptual review of structural racism highlights the promise of place-based interventions that target geographically defined communities, to engage residents and a range of institutions (across sectors) in order to ensure equitable access to resources and services, remediating the processes set in motion decades earlier. Clinicians play a role in linking patients to services, programming, and other resources and advocating for responsiveness in addressing gaps. Over time, concentrated efforts across sectors in targeted areas have shown improvement in a host of social outcomes, including health outcomes. Similarly, providing access to higher-quality housing, either with housing vouchers or housing lotteries, had unexpected positive health impacts. These findings are encouraging, as are the social policy interventions and systemic change, including legislation such as the Civil Rights Act, the advent of Medicare and Medicaid, and tenement regulations, associated with the narrowing of racial gaps.

Bibliography

Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL, McArdle N, Williams DR. Toward a policy-relevant analysis of geographic and racial/ethnic disparities in child health. Health Aff (Millwood) . 2008;27(2):321–333.

Anderson AT, Jackson A, Jones L, et al. Minority parents’ perspectives on racial socialization and school readiness in the early childhood period. Acad Pediatr . 2015;15(4):405–411.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet . 2017;389:1453–1463.

Bassett MT. #BlackLivesMatter: a challenge to the medical and public health communities. N Engl J Med . 2015;372(12):1085–1087.

Beck AF, Huang B, Auger KA, et al. Explaining racial disparities in child asthma readmission using a causal inference approach. JAMA Pediatr . 2016;170(7):695–703.

Chae DH, Clouston S, Martz CD, et al. Area racism and birth outcomes among Blacks in the United States. Soc Sci Med . 2018;199:49–55.

Colen CG, Ramey DM, Cooksey EC, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health among nonpoor African Americans and Hispanics: the role of acute and chronic discrimination. Soc Sci Med . 2018;199:167–180.

Escala MK, Hall BG. Dead wrong: the growing list of racial/ethnic disparities in childhood mortality. J Pediatr . 2015;166(4):790–793.

Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Acad Med . 2004;79(12):1139–1147.

Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev . 2011;8(1):115–132.

Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(22):2113–2116.

Krieger N. The ostrich, the albatross, and public health: an ecosocial perspective—or why an explicit focus on health consequences of discrimination and deprivation is vital for good science and public health practice. Public Health Rep . 2001;116(5):419–423.

Krieger N. Discrimination and health inequities. Int J Health Serv . 2014;44(4):643–710.

Maroney T, Zuckerman B. “The Talk,” Physician Version: Special considerations for African-American male adolescents. Pediatrics . 2018;141(2):e20171462.

McCluney CL, Schmitz LL, Hicken MT, Sonnega A. Structural racism in the workplace: does perception matter for health inequalities? Soc Sci Med . 2018;199:106–114.

NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet. https://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/ .

Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, et al. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and well-being for children and young people. Soc Sci Med . 2013;95:115–127.

Slopen N, Shonkoff JP, Albert MA, et al. Racial disparities in child adversity in the US: interactions with family immigration history and income. Am J Prev Med . 2016;50(1):47–56.

The Lancet. Living in colour—American children, race, and well-being. Lancet . 2016;388:307.

Umberson D, Olson JS, Crosnoe R, et al. Death of family members as an overlooked source of racial disadvantage in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2017;114(5):915–920.

US Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version) . National Academies Press: Washington, DC; 2003.

Washington HA, Baker RB, Olakanmi O, et al. Segregation, civil rights, and health disparities: the legacy of African American physicians and organized medicine, 1910–1968. J Natl Med Assoc . 2009;101(6):513–527.

Wilderman C, Wang EA. Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. Lancet . 2017;389:1464–1472.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep . 2001;116(5):404–416.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med . 2009;32(1):20–47.

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol . 2016;35(4):407–411.

Williams DR, Wyatt R. Racial Bias in Health Care and Health: challenges and opportunities. JAMA . 2015;314(6):555–556.