Strategies for Health Behavior Change

Cori M. Green, Anne M. Gadomski, Lawrence Wissow

To improve the health of children, pediatricians often ask patients and caregivers to make behavioral changes. These may be lifestyle changes to manage a chronic condition (e.g., obesity, asthma), adherence with the recommended timing and frequency of medications, or recommendations to seek assistance from other health providers (e.g., dieticians, mental health providers, physical, occupational, or speech therapists). However, change is difficult and can cause distress, and families often express reluctance or ambivalence to change due to perceived barriers. When families do not believe change is needed or possible, pediatricians may become discouraged or uncomfortable in providing care. This can make it difficult for clinicians to form an alliance with families, which is central to finding a solution to most problems identified in the medical setting.

Many healthcare problems may require complex, multifaceted interventions, but the first step is always to engage the family in identifying the healthcare problem driving the need for behavior change. Once a problem is identified and agreed on, clinicians and families need to set an achievable goal and identify specific behaviors that can help families reach their goal. It is important to be specific and precise about the actual behavior and not simply identify the category of the behavior. When counseling a patient on weight loss for obesity, for example, one might discuss 3 possible approaches: making dietary changes, increasing exercise, and decreasing screen time. The choice of which behavior to focus on should come from the patient but needs to be specific. It is not enough for the patient to state he will exercise more. Instead, the clinician should help the patient identify a more specific goal, such as playing basketball with his friends 3 times a week at the park near home. This takes in to account the action, context, setting, and time of the new behavioral goal. Specific examples of problems that would necessitate a behavior change to improve outcomes are used throughout the chapter.

Unified Theory of Behavior Change

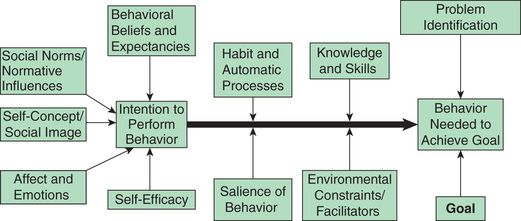

There are several theories of health-related behavior change. Each highlights a different concept, but frameworks that unite these theories suggest that the factor most predictive of whether one will perform a behavior is the intention to do so. The unified theory of behavior change examines behavior along 2 dimensions: influences on intent and moderators of the intention-behavior relationship (Fig. 17.1 ). Five main factors that influence one's decision to perform a behavior are expectancies, social norms/normative influences, self-concept/self-image, emotions, and self-efficacy. Table 17.1 provides specific examples on how to explore influences of intent when guiding families in decision-making, such as deciding to start a stimulant medication for a child diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is not necessary to ask about each influence, but these principles are particularly useful when guiding patients who may be resistant to change.

Table 17.1

ADHD, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Once a decision to make a change is made, 4 factors determine whether an intention leads to carrying out the behavior: knowledge and skills, environmental facilitators and constraints, salience of the behavior, and habits. The pediatrician can help ensure intent leads to behavior change by addressing these factors during the visit. In the ADHD example, the clinician can help the family build their knowledge by providing handouts on stimulants, nutritional pamphlets on how to minimize the appetite-suppressant effects of the medication on weight, and information on how the family can explain to others the need for medication. Asking about morning routines will help identify potential barriers in remembering to take the medication. Lastly, clinicians can help families think about cues for remembering to give the medication in the morning, since their morning routines, or habits, will have to be adjusted to adhere to this medication.

By using these principles of behavior change, pediatricians can guide their patients toward change during an encounter by ensuring they leave with (1) a strong positive intention to perform the behavior; (2) the perception that they have the skills to accomplish it; (3) a belief that the behavior is socially acceptable and consistent with their self-image; (4) a positive feeling about the behavior; (5) specific strategies in overcoming potential barriers in performing the behavior; and (6) a set of identified cues and enablers to help build new habits.

Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change

It is difficult to counsel families to change a behavior when they may not agree there is a problem or when they are not ready to build an intention to change. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change places an individual's motivation and readiness to change on a continuum. The premise of this model is that behavior change is a process, and as someone attempts to change, they move through 5 stages (although not always in a linear fashion): precontemplation (no current intention of making a change), contemplation (considering change), preparation (creating an intention, planning, and committing to change), action (has changed behavior for a short time), and maintenance (sustaining long-term change). Assessing a patient's stage of change and then targeting counseling toward that stage can help build a therapeutic alliance , in contrast to counseling a patient to do something she is not ready for, which can disrupt therapeutic alliance and lead to resistance. Table 17.2 further describes stages of change and gives examples for counseling that targets the adolescent's stage of change in reducing marijuana smoking.

Table 17.2

| STAGE/DEFINITION | GOAL AND STRATEGY | SPECIFIC EXAMPLES |

|---|---|---|

|

Precontemplation Not considering change. May be unaware that a problem exists. |

Establish a therapeutic relationship. Increase awareness of need to change. |

“I understand you are only here because your parents are worried and that you don't feel that smoking marijuana is a big deal.” “Can I ask if smoking marijuana has created any problems for you now? I know your parents were worried about your grades.” “It's up to you to decide if and when you are ready to cut back on smoking marijuana.” “Is it okay if I give you some information about marijuana use?” “I know it can be hard to change a habit when you feel under pressure. It is totally up to you to decide if cutting back is right for you. Is it okay if I ask you about this during our next visit?” |

|

Contemplation Beginning to consider making a change, but still feeling ambivalent about making a change. |

Identify ambivalence. Help develop discrepancy between goals and current behaviors. Ask about pros and cons of changing problem behavior. Support patient toward making a change. |

“I'm hearing that you do agree that sometimes your marijuana use does get in the way, especially with school. However, it helps relax you and it would be hard to make a change right now.” “What would be one benefit of cutting back? What would be a drawback to cutting back? Do you think your smoking will cause problems in the future?” “After talking about this, if you feel you want to cut back, the next step would be to think about how to best do that. We wouldn't need to jump right into a plan. Why don't you think about what we discussed, and we can meet next week if you are ready to make a plan?” |

|

Preparation Preparing for action. Reduced ambivalence and exploration of options for change. |

Help patient set a goal and prepare a concrete plan. Offer a menu of choices. Identify supports and barriers. |

“It's great that you are thinking about ways to cut back on your smoking. I understand your initial goal is to stop smoking during the week.” “I can give you some other options of how to relax and reduce stress during the week.” “We need to figure out how to react to your friends after school who you normally smoke with.” “Do you have other friends who you can see after school instead, who would support this decision?” |

|

Action Taking action; actively implementing plan. |

Provide positive feedback. Identify unexpected barriers and create coping strategies. |

“Congratulations on cutting back. Have you noticed any differences in your schoolwork? I'm so happy to hear your grades improved.” “Has it been difficult to not see your friends after school? How have you reacted when they get annoyed you don't want to smoke with them?” “Let's continue to track your progress.” |

|

Maintenance Continues to change behavior and maintains healthier lifestyle. |

Reinforce commitment and affirm ability to change. Create coping plans when relapse does occur. Manage triggers. |

“You really are committed to going to a good college and improving your grades. I'm so happy the hard work has paid off.” “I understand that it was hard to say no to smoking with your friends last week when it was someone's birthday. How did you feel after? Are there triggers that we can think about preventing in the future?” |

* This table uses an example of an adolescent who is initially resistant to cutting back on smoking marijuana. His parents caught him smoking in his room and arranged for him to see the pediatrician.

Adapted from Implementing mental health priorities in practice: substance use, American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Mental-Health/Pages/substance-use.aspx .

Common Factors Approach

Conversations around behavior change are most effective when they take place in a context of a trusting, mutually respectful relationship. The traditional medical model assumes that patients and their families come with questions and needs, and that the pediatrician's job is to offer specific advice and advocate for its acceptance. This approach fails when families are reluctant, ambivalent, demoralized, or unfamiliar with the healthcare system or the treatment choices offered. A context more supportive of behavior change can be developed when pediatricians use communication strategies that facilitate collaboration and building therapeutic alliance.

The common factors approach is an evidence-based communication strategy that is effective in facilitating behavior change. The skills central to a common factors approach are consistent across multiple forms of psychotherapy and can be viewed as generic aspects of treatment that can be used across a wide range of symptoms to build a therapeutic alliance between the physician and patient. This alliance predicts outcomes of counseling more than the specific modality of treatment. The common factors approach has been implemented and studied in pediatric primary care for children with mental health problems. Children who were treated by pediatricians trained in the common factors approach had improved functioning compared to those who saw pediatricians without this training.

A common factors approach distinguishes between the impact of the patient–provider alliance and the pediatrician's use of skills that influence patient behavior change across a broad range of conditions. Interpersonal skills that help build alliances with patients include showing empathy, warmth, and positive regard. Skills that influence behavior change include a clinician's ability to provide optimism, facilitate treatment engagement, and maintain the focus on achievable goals. This can be done by clearly explaining the condition and treatment approaches while keeping the discussion focused on immediate and practical concerns.

Interpersonal Skills: HEL2 P3

The interpersonal skills that facilitate an affective bond between the patient and clinician can be remembered by the HEL2 P3 mnemonic (Table 17.3 ). These skills include providing hope , empathy , and loyalty ; using the patient's language ; partnering with the family; asking permission to raise more sensitive questions or to give advice; and creating a plan that is initiated by the family. These interpersonal skills should help operationalize the common factors approach by increasing a patient's optimism, feelings of well-being, and willingness to work toward improved health, while also targeting feelings of anger, ambivalence, and hopelessness.

Table 17.3

| SKILL | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Hope for improvement: Develop strengths. | “I have seen other children like you with similar feelings of sadness, and they have gotten better.” |

| Empathy: Listen attentively. | “It must be hard for you that you no longer get pleasure in playing soccer.” |

| Language: Use family's language. Check understanding. | “Let me make sure I understand what you are saying. You no longer feel like doing things that make you happy in the past?” |

| Loyalty: Express support and commitment. | “You are free to talk to me about anything while we work through this.” |

|

Permission: Ask permission to explore sensitive subjects. Offer advice. Partnership: Identify and overcome barriers. |

“I would like to ask more questions that you may find more sensitive, is that okay?” “Is it okay with you if I give you my opinion on what may be the problem here?” |

| Plan: Establish a plan, or at least a first step family can take. | “If we work together, maybe we can think through solutions for the problems you identified.” |

* This table illustrates the interpersonal skills highlighted in the common factors approach. In this example the clinician is responding to an adolescent struggling with depression and resistant to seeking help.

Adapted with data from Foy JM, Kelleher KJ, Laraque D; American Academy of Pediatrics: Enhancing pediatric mental health care: strategies for preparing a primary care practice, Pediatrics 125(Suppl 3):S87–S108, 2010.

Structuring a patient encounter using common factors to facilitate behavior change uses these steps: eliciting concerns while setting an agenda and agreeing on the nature of the problem; establishing a plan; and responding to anger and demoralization and emphasizing hope.

Elicit Concerns: Set the Agenda and Agree on the Problem

The first step of the visit is to elicit both the child's and the parent's concerns and agree on the focus for the visit. This can be accomplished by using open-ended questions and asking “anything else?” until nothing else is disclosed. It is important to show you have time and are interested in their concerns by making eye contact, listening attentively, minimizing distractions, and responding with empathy and interest. Engage both the child and the parent by taking turns eliciting their concerns. It is helpful to summarize their story to reassure them you have heard and understand what they are saying. Keep the session organized, and manage rambling by gently interrupting, paraphrasing, asking for additional concerns, and refocusing the conversation.

By the end of this step in the visit, all parties should feel reassured that their problems were heard and accurately described. The next step is to agree on the problem to be addressed during that visit. If the parent and child do not agree on the issue, try to find a common thread that will address the concerns of both.

Establish a Plan

Once a problem is agreed on, the pediatrician can partner with families to develop acceptable and achievable plans for treatment or further evaluation. Families should take the lead in developing goals and the strategies to attain them, and information should be given in response to patients’ expressed needs. Pediatricians can involve families by offering choices and asking for feedback. Advice should be given only after asking a family's permission to do so. If the family asks for advice, the clinician should respond by considering principles of behavior change, as described earlier. Advice should be tailored toward the family's willingness to act, concerns for barriers, and attitudes and should be as specific and practical as possible. Once an initial plan is established, it is important to partner in monitoring responses and to provide continued support.

Respond to Anger and Demoralization and Emphasize Hope

The common factors approach is particularly helpful in engaging families in situations where anger and demoralization could prevent patients from being able to use the clinician's advice. Focusing the conversation on goals for the future and how to achieve them is more productive than discussing how problems began. This “solution-focused therapy” approach grew out of the need for clinicians to help people in a brief encounter. Hopelessness can be relieved by pediatricians helping patients to identify and build on strengths and past success, reframing events and feelings, and breaking down overwhelming goals into small, concrete steps that are more readily accomplished. In general, pediatricians can use the elicit-provide-elicit model . First, ask if they want to hear your thoughts about the situation. Provide guidance in a neutral way, and then ask the family what they think about what you just stated.

Table 17.4 provides an example of how to use common factors in practice using a scenario of an adolescent female who has been teased for using albuterol before physical education class for her exercise-induced asthma. The clinician in the scenario attempts to address both the patient's and her mother's concerns.

Table 17.4

Common Factors Approach in Practice*

| GOAL | SPECIFIC SKILLS | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|---|

| Elicit child and parents' concerns. | Use open-ended questions and ask, “What else?” until nothing else is listed, while engaging both parties and demonstrating empathy. |

“Hi, Jacqueline and Mrs. Smith. How have things been since last time? What are your biggest concerns for today?” “What else do you think we should put on the agenda for today?” “I am sorry to hear that you have had more asthma symptoms around gym time, Jacqueline. I'd like to ask you a few more questions to get a better understanding of what has changed, if that's okay with you.” “I understand this is upsetting you, Mrs. Smith, and that you worry that Jacqueline is not going to the nurse before gym to use her inhaler pump anymore. Let's hear from Jacqueline.” |

| Agree on the problem. | “Can we all agree that managing the asthma symptoms around gym time is the most pressing issue for today? Should we focus on that today?” | |

| Manage rambling. | “What you're saying is really important, but I want to be sure we have time to talk about controlling your daughter's asthma symptoms during gym. Is it okay if we go back to that topic?” | |

| Partner with families to find acceptable forms of treatment. | Develop acceptable plans for treatment of further diagnoses. |

“I believe we can develop a plan to help deal with this. Is it okay to start talking about next steps?” “I know these asthma symptoms are concerning to your mom. But, Jacqueline, is this something you can act on now?” “I am happy to give suggestions on how to more easily use your inhaler before gym, without the other kids noticing. But what were you thinking, Jacqueline?” “Let's make a specific plan on where you can keep your inhaler so the other kids don't see it.” |

| Address barriers to treatment. | “Is there anything that makes you worry that this may not work?” | |

| Increase expectations that treatment will be helpful. | Respond to hopelessness, anger, and frustration. |

“I realize it wasn't your choice to come here, Jacqueline, but I'm interested in hearing how you feel about this issue.” “It must be really hard for you, Jacqueline, when the kids tease you about your inhaler.” “It must be frustrating for the school nurse to call you in the middle of the day at work, Mrs. Smith.” “I would be angry, too, if I felt my mom didn't understand how it felt when I got teased for going to the nurse's office.” |

| Emphasize hope. | “We've managed difficult things before. Remember when Jacqueline kept getting admitted for her asthma when she was younger? We have come a long way since then, and I'm sure we can manage this as well.” |

* Jacqueline is an adolescent female who has had asthma since she was an infant. Despite multiple hospitalizations as an infant, her asthma had been under control except for during exercise, including physical education (PE) class. She had been going to the nurse's office to take albuterol before PE class, but recently she had been teased for having to take medication before PE. She has begun to skip treatments to avoid the teasing. However, her mother has now been called a few times to pick her up from school due to her asthma symptoms. Mrs. Smith is a single mother who cannot miss work and is very frustrated. She was not aware of the bullying Jacqueline has undergone.

This scenario is adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics curricula on common factors. https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Mental-Health/Pages/Module-1-Brief-Intervention.aspx .

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a goal-oriented, supportive counseling style that complements the HEL2 P3 framework and is useful when patients or families remain ambivalent about making health-related behavior changes. MI is designed to enhance intrinsic motivation in patients by exploring their perspectives and ambivalence. It is also aligned with the transtheoretical model's continuum of change, where the pediatrician not only tailors counseling to a patient's stage of change, but does so with the goal of moving the patient toward the next stage. It is particularly effective for those not interested in change or not ready to make a commitment. MI has been shown to be an effective intervention strategy for decreasing high-risk behaviors, improving chronic disease control, and increasing adherence to preventive health measures.

MI is a collaborative approach in which the pediatrician respects patients’ perspective and treats them as the “expert” on their values, beliefs, and goals. Collaboration, acceptance, compassion, and evocation are the foundation of MI and are referred to as the “spirit” of the approach. The clinician is a “guide,” respecting patients’ autonomy and their ability to make their own decision to change. The pediatrician expresses genuine concern and demonstrates that he or she understands and validates the patient's or family's struggle. Using open-ended questions, the pediatrician evokes the patient's own motivation for change.

Expressing empathy facilitates behavior change by accepting the patient's beliefs and behaviors. This contrasts to direct persuasion, which often leads to resistance. The pediatrician must reinforce that ambivalence is normal and use skillful reflective listening, showing the patient an understanding of the situation.

Developing a discrepancy between current behaviors (or treatment choices) and treatment goals motivates change and helps move the patient from the precontemplative stage to the contemplative stage or from the contemplative stage to preparation, as described in the transtheoretical model. Through MI the clinician can guide patients in understanding that their current behaviors may not be consistent with their stated goals and values.

Rolling with resistance , or not pushing back when suggestions are declined, is a strategy again to align with the patient. Resistance is usually a sign that a different approach is needed. As necessary, the clinician can ask permission to give new perspectives.

Self-efficacy, or a patient's belief in her ability to perform the behavior, is a key element for change and a powerful motivator. Clinicians can express confidence in the patient's ability to achieve change and support the patient's self-efficacy.

The process by which MI is used in a patient encounter involves the following 4 parts:

- 1. Engagement is the rapport-building part of the encounter. In addition to using the skills presented in the HEL2 P3 framework, the MI approach highlights the use of open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summaries (OARS ). Open-ended questions should be inviting and probing enabling the patient to think through and come to a better understanding of the problem and elicit their internal motivation. Affirmations provide positive feedback, express appreciation about a patient's strengths and can reinforce autonomy and self-efficacy. Reflective listening demonstrates that the clinician understands the patient's thoughts and feelings without judgement or interruption. It should be done frequently and can encourage the patient to be more open. Summarizing the conversation in a succinct way reinforces that you are listening, pulls together all information, and allows the patient to hear his own motivations and ambivalence.

- 2. Focusing the visit is done to clarify the patient's priorities, stage of readiness, and to identify the problem where there is ambivalence. If a patient remains resistant to change, ask permission to give information or share ideas and then ask for feedback on what they think about what you said. In the elicit-ask-elicit model , a clinician can deliver information about an unhealthy behavior or lifestyle decision in a nonpaternalistic manner.

- 3. Evocation is when the clinician assesses their patients’ reasons for change and helps them to explore advantages, disadvantages, and barriers to change. It is important to reinforce the patient's change talk. Examples of change talk include an expression of desire (“I want to…”), ability (“I can…”), reasons (“There are good reasons to…”), or a need for change (“I need to…”). Clinician can use “readiness rulers” by asking their patients to rate on a scale from 1 to 10 how important and confident they are in making change. The clinician should then respond by asking why the patient did not choose a lower number and should follow up asking what it would take to bring it to a higher number.

- 4.

The planning

stage is similar to that described in the discussion of a common factors approach and occurs once a patient is in the preparation stage on the continuum of change. A clinician can guide their patient through this stage by having them write down responses to statements such as, “The changes I want to make are…,” “The most important reasons to make this change are…,” “Some people who can support me are…,” and “They can help me by ….” A concrete plan should include specific actions and a way to factor in accountability and rewards. Table 17.5

uses a visit for counseling about obesity to demonstrate the process of motivational interviewing.

Table 17.5

Counseling for Obesity Using a Motivational Interviewing (MI) Approach

ACTION SPECIFIC SKILLS EXAMPLES Engagement* O pen-ended questions “Now that we have finished the majority of the visit, I'd like to talk about your weight. Is that okay? How do you feel about your size?”

“Mrs. Smith, how do you feel about Jimmy's weight?”

A ffirmations “You definitely have shown how strong you are having dealt with kids teasing you about your size.”

“Remember when you were having difficulty with school? You were able to make a few changes, and now you are doing well. I am confident we can do the same with your weight.”

R eflective listening “You are feeling like your son is the same size as everyone in your family, and you aren't concerned right now.”

“Having your family watch TV before bed really works for your family, Mrs. Smith.”

“You're not terribly excited about having to think of ways to cook differently.”

S ummary statements “So far, we have discussed how challenging it would be to lose weight and make changes for the whole family, but you are willing to consider some simple changes.” Focusing Set the agenda. “We could talk about increasing the amount of exercise Jimmy has every week, reducing screen time, or making a dietary change. What do you think would work best?”

“Great, so we will talk about soda. What do you like about it? How many times a week do you drink it?”

Evocation Reinforce any change talk.

Change ruler.

“Those are great reasons for thinking about cutting back on soda.”

“On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident are you (or important is it) that you can cut back on soda?”

“A 5. Why didn't you answer a 3?”

“What would it take to bring it to a 7?”

Planning Focus on how to make the change, not “why” anymore.

Be concrete.

“Maybe completely eliminating soda is too difficult right now. Do you want to think of a couple of times during the week where you can reward yourself with a soda?”

“What will you drink after school instead of soda?”

* OARS is used to engage the patient and build rapport.

Adapted from Changing the conversation about childhood obesity, American Academy of Pediatrics, Institute for Healthy Childhood Weight. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/Changing-the-conversation-about-Childhood-Obesity.aspx .

Shared Decision-Making

Shared decision-making has many similarities to the processes previously described in that it emphasizes moving physicians away from a paternalistic approach in dictating treatment to one where patients and clinicians collaborate in making a medical decision, particularly when multiple evidence-based treatments options exist. The pediatrician or clinician offers different treatment options and describes the risks and benefits for each one. The patient or caregiver expresses their values, preferences, and treatment goals, and a decision is made together.

Shared decision-making is often facilitated by using evidence-based decision aids such as pamphlets, videos, web-based tools, or educational workshops. Condition-specific or more generic decision aids have been created and facilitate the process of shared decision-making. Studies in adults show that such aids improve knowledge and satisfaction, reduce decisional conflict, and increase the alignment between patient preferences and treatment options. More study is needed to assess behavioral and physiologic outcomes specifically when involving children in the decision-making process.