Vitamin B Complex Deficiencies and Excess

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Vitamin B complex includes a number of water-soluble nutrients, including thiamine (vitamin B1 ), riboflavin (B2 ), niacin (B3 ), pyridoxine (B6 ), folate, cobalamin (B12 ), biotin, and pantothenic acid. Choline and inositol are also considered part of the B complex and are important for normal body functions, but specific deficiency syndromes have not been attributed to a lack of these factors in the diet.

B-complex vitamins serve as coenzymes in many metabolic pathways that are functionally closely related. Consequently, a lack of one of the vitamins has the potential to interrupt a chain of chemical processes, including reactions that are dependent on other vitamins, and ultimately can produce diverse clinical manifestations. Because diets deficient in any one of the B-complex vitamins are often poor sources of other B vitamins, manifestations of several vitamin B deficiencies usually can be observed in the same person. It is therefore a general practice in a patient who has evidence of deficiency of a specific B vitamin to treat with the entire B-complex group of vitamins.

Thiamine (Vitamin B1 )

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Thiamine diphosphate, the active form of thiamine, serves as a cofactor for several enzymes involved in carbohydrate catabolism such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, transketolase, and α-ketoglutarate. These enzymes also play a role in the hexose monophosphate shunt that generates nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) and pentose for nucleic acid synthesis. Thiamine is also required for the synthesis of acetylcholine (ACh) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which have important roles in nerve conduction. Thiamine is absorbed efficiently in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and may be deficient in persons with GI or liver disease. The requirement of thiamine is increased when carbohydrates are taken in large amounts and during periods of increased metabolism, such as fever, muscular activity, hyperthyroidism, pregnancy, and lactation. Alcohol affects various aspects of thiamine transport and uptake, contributing to the deficiency in alcoholics.

Pork (especially lean), fish, and poultry are good nonvegetarian dietary sources of thiamine. Main sources of thiamine for vegetarians are rice, oat, wheat, and legumes. Most ready-to-eat breakfast cereals are enriched with thiamine. Thiamine is water soluble and heat labile; most of the vitamin is lost when the rice is repeatedly washed and the cooking water is discarded. The breast milk of a well-nourished mother provides adequate thiamine; breastfed infants of thiamine-deficient mothers are at risk for deficiency. Thiamine antagonists (coffee, tea) and thiaminases (fermented fish) may contribute to thiamine deficiency. Most infants and older children consuming a balanced diet obtain an adequate intake of thiamine from food and do not require supplements.

Thiamine Deficiency

Deficiency of thiamine is associated with severely malnourished states, including malignancy and following surgery. The disorder (or spectrum of disorders) is classically associated with a diet consisting largely of polished rice (oriental beriberi); it can also arise if highly refined wheat flour forms a major part of the diet, in alcoholic persons, and in food faddists (occidental beriberi). Thiamine deficiency has often been reported from inhabitants of refugee camps consuming the polished rice–based monotonous diets. Low thiamine concentrations are also noted during critical illnesses.

Thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anemia (TRMA) syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by megaloblastic anemia, diabetes mellitus, and sensorineural hearing loss, responding in varying degrees to thiamine treatment. The syndrome occurs because of mutations in the SLC19A2 gene, encoding a thiamine transporter protein, leading to abnormal thiamine transportation and cellular vitamin deficiency. Another dependency state, biotin and thiamine–responsive basal ganglia disease , results from mutations in the SLC19A3 gene; presents with lethargy, poor contact, and poor feeding in early infancy; and responds to combined treatment with biotin and thiamine. Thiamine and related vitamins may improve the outcome in children with Leigh encephalomyelopathy and type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Clinical Manifestations

Thiamine deficiency can develop within 2-3 mo of a deficient intake. Early symptoms of thiamine deficiency are nonspecific, such as fatigue, apathy, irritability, depression, drowsiness, poor mental concentration, anorexia, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. As the condition progresses, more-specific manifestations of beriberi develop, such as peripheral neuritis (manifesting as tingling, burning, paresthesias of the toes and feet), decreased deep tendon reflexes, loss of vibration sense, tenderness and cramping of the leg muscles, heart failure, and psychologic disturbances. Patients can have ptosis of the eyelids and atrophy of the optic nerve. Hoarseness or aphonia caused by paralysis of the laryngeal nerve is a characteristic sign. Muscle atrophy and tenderness of the nerve trunks are followed by ataxia, loss of coordination, and loss of deep sensation. Later signs include increased intracranial pressure, meningismus, and coma. The clinical picture of thiamine deficiency is usually divided into a dry (neuritic ) type and a wet (cardiac ) type. The disease is wet or dry depending on the amount of fluid that accumulates in the body because of cardiac and renal dysfunction, even though the exact cause for this edema is unknown. Many cases of thiamine deficiency show a mixture of both features and are more properly termed thiamine deficiency with cardiopathy and peripheral neuropathy .

The classic clinical triad of Wernicke encephalopathy —mental status changes, ocular signs, and ataxia—is rarely reported in infants and young children with severe deficiency secondary to malignancies or feeding of defective formula. An epidemic of life-threatening thiamine deficiency was seen in infants fed a defective soy-based formula that had undetectable thiamine levels. Manifestations included emesis, lethargy, restlessness, ophthalmoplegia, abdominal distention, developmental delay, failure to thrive (malnutrition), lactic acidosis, nystagmus, diarrhea, apnea, seizures, and auditory neuropathy. An acute presentation with tachycardia, moaning, and severe metabolic acidosis responding to parenteral thiamine has been occasionally reported in infants of mothers consuming polished and frequently washed rice.

Death from thiamine deficiency usually is secondary to cardiac involvement. The initial signs are cyanosis and dyspnea, but tachycardia, enlargement of the liver, loss of consciousness, and convulsions can develop rapidly. The heart, especially the right side, is enlarged. The electrocardiogram (ECG) shows an increased QT interval, inverted T waves, and low voltage. These changes, as well as the cardiomegaly, rapidly revert to normal with treatment, but without prompt treatment, cardiac failure can develop rapidly and result in death. In fatal cases of beriberi, lesions are principally located in the heart, peripheral nerves, subcutaneous tissue, and serous cavities. The heart is dilated, and fatty degeneration of the myocardium is common. Generalized edema or edema of the legs, serous effusions, and venous engorgement are often present. Degeneration of myelin and axon cylinders of the peripheral nerves, with wallerian degeneration beginning in the distal locations, is also common, particularly in the lower extremities. Lesions in the brain include vascular dilation and hemorrhage.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is often suspected based on clinical setting and compatible symptoms. A high index of suspicion in children presenting with unexplained cardiac failure may sometimes be lifesaving. Objective biochemical tests of thiamine status include measurement of erythrocyte transketolase activity and the thiamine pyrophosphate effect. The biochemical diagnostic criteria of thiamine deficiency consist of low erythrocyte transketolase activity and high thiamine pyrophosphate effect (normal range: 0–14%). Urinary excretion of thiamine or its metabolites (thiazole or pyrimidine) after an oral loading dose of thiamine may also be measured to help identify the deficiency state. MRI changes of thiamine deficiency in infants are characterized by bilateral symmetric hyperintensities of the basal ganglia and frontal lobe, in addition to the lesions in the mammillary bodies, periaqueductal region, and thalami described in adults.

Prevention

A maternal diet containing sufficient amounts of thiamine prevents thiamine deficiency in breastfed infants, and infant formulas marketed in all developed countries provide recommended levels of intake. During complementary feeding, adequate thiamine intake can be achieved with a varied diet that includes meat and enriched or whole-grain cereals. When the staple cereal is polished rice, special efforts need to be made to include legumes and/or nuts in the ration. Thiamine and other vitamins can be retained in rice by parboiling, a process of steaming the rice in the husk before milling. Improvement in cooking techniques, such as not discarding the water used for cooking, minimal washing of grains, and reduction of cooking time helps to minimize the thiamine losses during the preparation of food. Thiamine supplementation should be ensured during total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Treatment

In the absence of GI disturbances, oral administration of thiamine is effective. Children with cardiac failure, convulsions, or coma should be given 10 mg of thiamine intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) daily for the 1st wk. This treatment should then be followed by 3-5 mg/day of thiamine orally (PO) for at least 6 wk. The response is dramatic in infants and in those having predominantly cardiovascular manifestations, whereas the neurologic response is slow and often incomplete. Epilepsy, mental disability, and language and auditory problems of varying degree have been reported in survivors of severe infantile thiamine deficiency.

Patients with beriberi often have other B-complex vitamin deficiencies; therefore, all other B-complex vitamins should also be administered. Treatment of TRMA and other dependency states require higher dosages (100-200 mg/day). The anemia responds well to thiamine administration, and insulin for associated diabetes mellitus can also be discontinued in many patients with TRMA syndrome.

Thiamine Toxicity

There are no reports of adverse effects from consumption of excess thiamine by ingestion of food or supplements. A few isolated cases of pruritus and anaphylaxis have been reported in patients after parenteral administration of vitamin B1 .

Bibliography

Beshlawi I, Al Zadjali S, Bashir W, et al. Thiamine responsive megaloblastic anemia: the puzzling phenotype. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2014;61:528–531.

Dabar G, Harmouche C, Habr B, et al. Shoshin beriberi in critically-ill patients: case series. Nutr J . 2015;14:51.

Frank LL. Thiamin in clinical practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr . 2015;39:503–520.

Qureshi UA, Sami A, Altaf U, et al. Thiamine responsive acute life threatening metabolic acidosis in exclusively breast-fed infants. Nutrition . 2016;32:213–216.

Tabarki B, Alfadhel M, AlShahwan S, et al. Treatment of biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease: open comparative study between the combination of biotin plus thiamine versus thiamine alone. Eur J Paediatr Neurol . 2015;19:547–552.

Wani NA, Qureshi UA, Jehangir M, et al. Infantile encephalitic beriberi: magnetic resonance imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol . 2016;46:96–103.

Ygberg S, Naess K, Eriksson M, et al. Biotin and thiamine responsive basal ganglia disease: a vital differential diagnosis in infants with severe encephalopathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol . 2016;20:457–461.

Riboflavin (Vitamin B2 )

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Riboflavin is part of the structure of the coenzymes flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and flavin mononucleotide, which participate in oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions in numerous metabolic pathways and in energy production via the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Riboflavin is stable to heat but is destroyed by light. Milk, eggs, organ meats, legumes, and mushrooms are rich dietary sources of riboflavin. Most commercial cereals, flours, and breads are enriched with riboflavin.

Riboflavin Deficiency

The causes of riboflavin deficiency (ariboflavinosis ) are mainly related to malnourished and malabsorptive states, including GI infections. Treatment with some drugs, such as probenecid, phenothiazine, or oral contraceptives (OCs), can also cause the deficiency. The side chain of the vitamin is photochemically destroyed during phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia, since it is involved in the photosensitized oxidation of bilirubin to more polar excretable compounds.

Isolated complex II deficiency , a rare mitochondrial disease manifesting in infancy and childhood, responds favorably to riboflavin supplementation and thus can be termed a dependency state. Brown-Vialetto-Van Laere syndrome (BVVLS) , a rare, potentially lethal neurologic disorder characterized by rapidly progressive neurologic deterioration, peripheral neuropathy, hypotonia, ataxia, sensorineural hearing loss, optic atrophy, pontobulbar palsy, and respiratory insufficiency, responds to treatment with high doses of riboflavin if treated early in the disease course. Mutations in SLC52A2 gene (autosomal recessive), encoding riboflavin transporter proteins, have been identified in children with BVVLS.

Clinical Manifestations

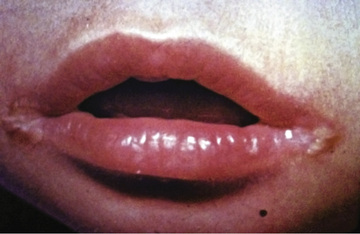

Clinical features of nutritional riboflavin deficiency include cheilosis, glossitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, photophobia, lacrimation, corneal vascularization, and seborrheic dermatitis. Cheilosis begins with pallor at the angles of the mouth and progresses to thinning and maceration of the epithelium, leading to fissures extending radially into the skin (Fig. 62.1 ). In glossitis the tongue becomes smooth, with loss of papillary structure (Fig. 62.2 ). Normochromic, normocytic anemia may also be seen because of the impaired erythropoiesis. A low riboflavin content of the maternal diet has been linked to congenital heart defects, but the evidence is weak.

Diagnosis

Most often, the diagnosis is based on the clinical features of angular cheilosis in a malnourished child, who responds promptly to riboflavin supplementation. A functional test of riboflavin status is done by measuring the activity of erythrocyte glutathione reductase (EGR), with and without the addition of FAD. An EGR activity coefficient (ratio of EGR activity with added FAD to EGR activity without FAD) of >1.4 is used as an indicator of deficiency. Urinary excretion of riboflavin <30 µg/24 hr also suggests low intakes.

Prevention

Table 62.1 lists the recommended daily allowance of riboflavin for infants, children, and adolescents. Adequate consumption of milk, milk products, and eggs prevents riboflavin deficiency. Fortification of cereal products is helpful for those who follow vegan diets or who are consuming inadequate amounts of milk products for other reasons.

Table 62.1

| NAMES AND SYNONYMS | BIOCHEMICAL ACTION | EFFECTS OF DEFICIENCY | TREATMENT OF DEFICIENCY | CAUSES OF DEFICIENCY | DIETARY SOURCES | RDA* BY AGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiamine (vitamin B1 ) |

Coenzyme in carbohydrate metabolism Nucleic acid synthesis Neurotransmitter synthesis |

Neurologic (dry beriberi): irritability, peripheral neuritis, muscle tenderness, ataxia Cardiac (wet beriberi): tachycardia, edema, cardiomegaly, cardiac failure |

3-5 mg/day PO thiamine for 6 wk |

Polished rice–based diets Malabsorptive states Severe malnutrition Malignancies Alcoholism |

Meat, especially pork; fish; liver Rice (unmilled), wheat germ; enriched cereals; legumes |

0-6 mo: 0.2 mg/day 7-12 mo: 0.3 mg/day 1-3 yr: 0.5 mg/day 4-8 yr: 0.6 mg/day 9-13 yr: 0.9 mg/day 14-18 yr: |

| Riboflavin (vitamin B2 ) | Constituent of flavoprotein enzymes important in redox reactions: amino acid, fatty acid, and carbohydrate metabolism and cellular respiration | Glossitis, photophobia, lacrimation, corneal vascularization, poor growth, cheilosis | 3-10 mg/day PO riboflavin |

Severe malnutrition Malabsorptive states Prolonged treatment with phenothiazines, probenecid, or OCPs |

Milk, milk products, eggs, fortified cereals, green vegetables |

0-6 mo: 0.3 mg/day 7-12 mo: 0.4 mg/day 1-3 yr: 0.5 mg/day 4-8 yr: 0.6 mg/day 9-13 yr: 0.9 mg/day 14-18 yr: |

| Niacin (vitamin B3 ) | Constituent of NAD and NADP, important in respiratory chain, fatty acid synthesis, cell differentiation, and DNA processing | Pellagra manifesting as diarrhea, symmetric scaly dermatitis in sun-exposed areas, and neurologic symptoms of disorientation and delirium | 50-300 mg/day PO niacin |

Predominantly maize-based diets Anorexia nervosa Carcinoid syndrome |

Meat, fish, poultry Cereals, legumes, green vegetables |

0-6 mo: 2 mg/day 7-12 mo: 4 mg/day 1-3 yr: 6 mg/day 4-8 yr: 8 mg/day 9-13 yr: 12 mg/day 14-18 yr: |

| Pyridoxine (vitamin B6 ) | Constituent of coenzymes for amino acid and glycogen metabolism, heme synthesis, steroid action, neurotransmitter synthesis |

Irritability, convulsions, hypochromic anemia Failure to thrive Oxaluria |

5-25 mg/day PO for deficiency states 100 mg IM or IV for pyridoxine-dependent seizures |

Prolonged treatment with INH, penicillamine, OCPs | Fortified ready-to-eat cereals, meat, fish, poultry, liver, bananas, rice, potatoes |

0-6 mo: 0.1 mg/day 7-12 mo: 0.3 mg/day 1-3 yr: 0.5 mg/day 4-8 yr: 0.6 mg/day 9-13 yr: 1.0 mg/day 14-18 yr: |

| Biotin | Cofactor for carboxylases, important in gluconeogenesis, fatty acid and amino acid metabolism | Scaly periorificial dermatitis, conjunctivitis, alopecia, lethargy, hypotonia, and withdrawn behavior | 1-10 mg/day PO biotin |

Consumption of raw eggs for prolonged periods Parenteral nutrition with infusates lacking biotin Valproate therapy |

Liver, organ meats, fruits |

0-6 mo: 5 µg/day 7-12 mo: 6 µg/day 1-3 yr: 8 µg/day 4-8 yr: 12 µg/day 9-13 yr: 20 µg/day 14-18 yr: 25 µg/day |

| Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5 ) | Component of coenzyme A and acyl carrier protein involved in fatty acid metabolism | Experimentally produced deficiency in humans: irritability, fatigue, numbness, paresthesias (burning feet syndrome), muscle cramps | Isolated deficiency extremely rare in humans |

Beef, organ meats, poultry, seafood, egg yolk Yeast, soybeans, mushrooms |

0-6 mo: 1.7 mg/day 7-12 mo: 1.8 mg/day 1-3 yr: 2 mg/day 4-8 yr: 3 mg/day 9-13 yr: 4 mg/day 14-18 yr: 5 mg/day |

|

| Folic acid | Coenzymes in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism as an acceptor and donor of 1-carbon units |

Megaloblastic anemia Growth retardation, glossitis Neural tube defects in progeny |

0.5-1 mg/day PO folic acid |

Malnutrition Malabsorptive states Malignancies Hemolytic anemias Anticonvulsant therapy |

Enriched cereals, beans, leafy vegetables, citrus fruits, papaya |

0-6 mo: 65 µg/day 7-12 mo: 80 µg/day 1-3 yr: 150 µg/day 4-8 yr: 200 µg/day 9-13 yr: 300 µg/day 14-18 yr: 400 µg/day |

| Cobalamin (vitamin B12 ) |

As deoxyadenosylcobalamin, acts as cofactor for lipid and carbohydrate metabolism As methylcobalamin, important for conversion of homocysteine to methionine and folic acid metabolism |

Megaloblastic anemia, irritability, developmental delay, developmental regression, involuntary movements, hyperpigmentation | 1,000 µg IM vitamin B12 |

Vegan diets Malabsorptive states Crohn disease Intrinsic factor deficiency (pernicious anemia) |

Organ meats, sea foods poultry, egg yolk, milk, fortified ready-to-eat cereals |

0-6 mo: 0.4 µg/day 7-12 mo: 0.5 µg/day 1-3 yr: 0.9 µg/day 4-8 yr: 1.2 µg/day 9-13 yr: 1.8 µg/day 14-18 yr: 2.4 µg/day |

| Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) |

Important for collagen synthesis, metabolism of cholesterol and neurotransmitters Antioxidant functions and nonheme iron absorption |

Scurvy manifesting as irritability, tenderness and swelling of legs, bleeding gums, petechiae, ecchymoses, follicular hyperkeratosis, and poor wound healing | 100-200 mg/day PO ascorbic acid for up to 3 mo |

Predominantly milk-based (non–human milk) diets Severe malnutrition |

Citrus fruits and fruit juices, peppers, berries, melons, tomatoes, cauliflower, leafy green vegetables |

0-6 mo: 40 mg/day 7-12 mo: 50 mg/day 1-3 yr: 15 mg/day 4-8 yr: 25 mg/day 9-13 yr: 45 mg/day 14-18 yr: |

* For healthy breastfed infants, the values represent adequate intakes, that is, the mean intake of apparently “normal” infants.

PO, Orally, IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; INH, isoniazid; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; OCP, oral contraceptive pill; RDA, recommended dietary allowance.

From Dietary reference intakes (DRIs): Recommended dietary allowances and adequate intakes, vitamins, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academies. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Nutrition/DRI-Tables/2_%20RDA%20and%20AI%20Values_Vitamin%20and%20Elements.pdf?la=en .

Treatment

Treatment includes oral administration of 3-10 mg/day of riboflavin, often as an ingredient of a vitamin B–complex mix. The child should also be given a well-balanced diet, including milk and milk products.

Riboflavin Toxicity

No adverse effects associated with riboflavin intakes from food or supplements have been reported, and the upper safe limit for consumption has not been established. Although the photosensitizing property of vitamin B2 suggests some potential risks, limited absorption in high-intake situations precludes such concerns.

Bibliography

Foley AR, Menezes MP, Pandraud A, et al. Treatable childhood neuronopathy caused by mutations in riboflavin transporter RFVT2. Brain . 2014;137:44–56.

Nichols EK, Talley LE, Birungi N, et al. Suspected outbreak of riboflavin deficiency among populations reliant on food assistance: a case study of drought-stricken Karamoja, Uganda, 2009–2010. PLoS ONE . 2013;8:e62976.

Sherwood M, Goldman RD. Effectiveness of riboflavin in pediatric migraine prevention. Can Fam Physician . 2014;60:244–246.

Swaminathan S, Thomas T, Kurpad AV. B-vitamin interventions for women and children in low-income populations. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care . 2015;18:295–306.

Niacin (Vitamin B3 )

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Niacin (nicotinamide or nicotinic acid) forms part of two cofactors, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NADP, which are important in several biologic reactions, including the respiratory chain, fatty acid and steroid synthesis, cell differentiation, and DNA processing. Niacin is rapidly absorbed from the stomach and the intestines and can also be synthesized from tryptophan in the diet.

Major dietary sources of niacin are meat, fish, and poultry for nonvegetarians and cereals, legumes, and green leafy vegetables for vegetarians. Enriched and fortified cereal products and legumes also are major contributors to niacin intake. Milk and eggs contain little niacin but are good sources of tryptophan, which can be converted to NAD (60 mg tryptophan = 1 mg niacin).

Niacin Deficiency

Pellagra , the classic niacin deficiency disease, occurs chiefly in populations where corn (maize), a poor source of tryptophan, is the major foodstuff. A severe dietary imbalance, such as in anorexia nervosa and in war or famine conditions, also can cause pellagra. Pellagra can also develop in conditions associated with disturbed tryptophan metabolism, such as carcinoid syndrome and Hartnup disease.

Clinical Manifestations

The early symptoms of pellagra are vague: anorexia, lassitude, weakness, burning sensation, numbness, and dizziness. After a long period of deficiency, the classic triad of dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia appears. Dermatitis , the most characteristic manifestation of pellagra, can develop suddenly or insidiously and may be initiated by irritants, including intense sunlight. The lesions first appear as symmetric areas of erythema on exposed surfaces, resembling sunburn, and might go unrecognized. The lesions are usually sharply demarcated from the surrounding healthy skin, and their distribution can change frequently. The lesions on the hands and feet often have the appearance of a glove or stocking (Fig. 62.3 ). Similar demarcations can also occur around the neck (Casal necklace ) (Fig. 62.3 ). In some cases, vesicles and bullae develop (wet type). In others there may be suppuration beneath the scaly, crusted epidermis; in still others the swelling can disappear after a short time, followed by desquamation (Fig. 62.4 ). The healed parts of the skin might remain pigmented. The cutaneous lesions may be preceded by or accompanied by stomatitis, glossitis, vomiting, and diarrhea. Swelling and redness of the tip of the tongue and its lateral margins is often followed by intense redness, even ulceration, of the entire tongue and the papillae. Nervous symptoms include depression, disorientation, insomnia, and delirium.

The classic symptoms of pellagra usually are not well developed in infants and young children, but anorexia, irritability, anxiety, and apathy are common. Young patients might also have sore tongues and lips and usually have dry scaly skin. Diarrhea and constipation can alternate, and anemia can occur. Children who have pellagra often have evidence of other nutritional deficiency diseases.

Diagnosis

Because of lack of a good functional test to evaluate niacin status, the diagnosis of deficiency is usually made from the physical signs of glossitis, GI symptoms, and a symmetric dermatitis. Rapid clinical response to niacin is an important confirmatory test. A decrease in the concentration and/or a change in the proportion of the niacin metabolites N1 -methyl-nicotinamide and 2-pyridone in the urine provide biochemical evidence of deficiency and can be seen before the appearance of overt signs of deficiency. Histopathologic changes from the affected skin include dilated blood vessels without significant inflammatory infiltrates, ballooning of the keratinocytes, hyperkeratosis, and epidermal necrosis.

Prevention

Adequate intakes of niacin are easily met by consumption of a diet that consists of a variety of foods and includes meat, eggs, milk, and enriched or fortified cereal products. The dietary reference intake (DRI) is expressed in milligram niacin equivalents (NE) in which 1 mg NE = 1 mg niacin or 60 mg tryptophan. An intake of 2 mg of niacin is considered adequate for infants 0-6 mo of age, and 4 mg is adequate for infants 7-12 mo. For older children, the recommended intakes are 6 mg for 1-3 yr of age, 8 mg for 4-8 yr, 12 mg for 9-13 yr, and 14-16 mg for 14-18 yr of age.

Treatment

Children usually respond rapidly to treatment. A liberal and varied diet should be supplemented with 50-300 mg/day of niacin; in severe cases or in patients with poor intestinal absorption, 100 mg may be given IV. The diet should also be supplemented with other vitamins, especially other B-complex vitamins. Sun exposure should be avoided during the active phase of pellagra, and the skin lesions may be covered with soothing applications. Other coexisting nutrient deficiencies such as iron-deficiency anemia should be treated. Even after successful treatment, the diet should continue to be monitored to prevent recurrence.

Niacin Toxicity

No toxic effects are associated with the intake of naturally occurring niacin in foods. Shortly after the ingestion of large doses of nicotinic acid taken as a supplement or a pharmacologic agent, a person often experiences a burning, tingling, and itching sensation as well as flushing on the face, arms, and chest. Large doses of niacin also can have nonspecific GI effects and can cause cholestatic jaundice or hepatotoxicity. Tolerable upper intake levels for children are approximately double the recommended dietary allowance.

Bibliography

Brown TM. Pellagra: an old enemy of timeless importance. Psychosomatics . 2010;51:93–97.

Lanska DJ. Chapter 30: historical aspects of the major neurological vitamin deficiency disorders: the water-soluble B vitamins. Handb Clin Neurol . 2010;95:445–476.

Piqué-Duran E, Pérez-Cejudo JA, Cameselle D, et al. Pellagra: a clinical, histopathological, and epidemiological study of 7 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr . 2012;103:51–58.

Steffen C. Pellagra. Skinmed . 2012;10:174–179.

Wan P, Moat S, Anstey A. Pellagra: a review with emphasis on photosensitivity. Br J Dermatol . 2011;164:1188–1200.

Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine)

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Vitamin B6 includes a group of closely related compounds: pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine, and their phosphorylated derivatives. Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) and, to a lesser extent, pyridoxamine phosphate function as coenzymes for many enzymes involved in amino acid metabolism, neurotransmitter synthesis, glycogen metabolism, and steroid action. If vitamin B6 is lacking, glycine metabolism can lead to oxaluria. The major excretory product in the urine is 4-pyridoxic acid.

The vitamin B6 content of human milk and infant formulas is adequate. Good food sources of the vitamin include fortified ready-to-eat cereals, meat, fish, poultry, liver, bananas, rice, and certain vegetables. Large losses of the vitamin can occur during high-temperature processing of foods or milling of cereals, whereas parboiling of rice prevents its loss.

Vitamin B6 Deficiency

Because of the importance of vitamin B6 in amino acid metabolism, high protein intakes can increase the requirement for the vitamin; the recommended daily allowances are sufficient to cover the expected range of protein intake in the population. The risk of deficiency is increased in persons taking medications that inhibit the activity of vitamin B6 (e.g., isoniazid, penicillamine, corticosteroids, phenytoin, carbamazepine), in young women taking oral progesterone-estrogen OCs, and in patients receiving maintenance dialysis.

Clinical Manifestations

The vitamin B6 deficiency symptoms seen in infants are listlessness, irritability, seizures, vomiting, and failure to thrive. Peripheral neuritis is a feature of deficiency in adults but is not usually seen in children. Electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities have been reported in infants as well as in young adults in controlled depletion studies. Skin lesions include cheilosis, glossitis, and seborrheic dermatitis around the eyes, nose, and mouth. Microcytic anemia can occur in infants but is not common. Oxaluria, oxalic acid bladder stones, hyperglycinemia, lymphopenia, decreased antibody formation, and infections also are associated with vitamin B6 deficiency.

Several types of vitamin B6 dependence syndromes , presumably resulting from errors in enzyme structure or function, respond to very large amounts of pyridoxine. These syndromes include pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy, a vitamin B6 –responsive anemia, xanthurenic aciduria, cystathioninuria, and homocystinuria (see Chapter 103 ). Pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy involves mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene causing deficiency of antiquitin, an enzyme involved in dehydrogenation of L -α-aminoadipic semialdehyde.

Diagnosis

The activity of aspartate (glutamic-oxaloacetic) transaminase (AST) and alanine (glutamic-pyruvic) transaminase (ALT) is low in vitamin B6 deficiency; tests measuring the activity of these enzymes before and after the addition of PLP may be useful as indicators of vitamin B6 status. Abnormally high xanthurenic acid excretion after tryptophan ingestion also provides evidence of deficiency. Plasma PLP assays are being used more often, but factors such as inflammation, renal function, and hypoalbuminemia can influence the results. Ratios between substrate-products pairs (e.g., PAr index, 3-hydroxykynurenine/xanthurenic acid ratio, oxoglutarate/glutamate ratio) may attenuate such influence. Quantification of a large number of metabolites, using mass spectrometry–based metabolomics, are being evaluated as functional biomarkers of pyridoxine status.

Vitamin B6 deficiency or dependence should be suspected in all infants with seizures . If more common causes of infantile seizures have been eliminated, 100 mg of pyridoxine can be injected, with EEG monitoring if possible. If the seizure stops, vitamin B6 deficiency should be suspected. In older children, 100 mg of pyridoxine may be injected IM while the EEG is being recorded; a favorable response of the EEG suggests pyridoxine deficiency.

Prevention

Deficiency is unlikely in children consuming diets that meet their energy needs and contain a variety of foods. Parboiling of rice prevents the loss of vitamin B6 from the grains. The DRIs for vitamin B6 are 0.1 mg/day for infants up to 6 mo of age; 0.3 mg/day for 6 mo to 1 yr; 0.5 mg/day for 1-3 yr; 0.6 mg/day for 4-8 yr; 1.0 mg/day for 9-13 yr; and 1.2-1.3 mg/day for 14-18 yr. Infants whose mothers have received large doses of pyridoxine during pregnancy are at increased risk for seizures from pyridoxine dependence, and supplements during the 1st few weeks of life should be considered. Any child receiving a pyridoxine antagonist, such as isoniazid, should be carefully observed for neurologic manifestations; if these develop, vitamin B6 should be administered or the dose of the antagonist should be decreased.

Treatment

Intramuscular or intravenous administration of 100 mg of pyridoxine is used to treat convulsions caused by vitamin B6 deficiency. One dose should be sufficient if adequate dietary intake follows. For pyridoxine-dependent children, daily doses of 2-10 mg IM or 10-100 mg PO may be necessary.

Vitamin B6 Toxicity

Adverse effects have not been associated with high intakes of vitamin B6 from food sources. However, ataxia and sensory neuropathy have been reported with dosages as low as 100 mg/day in adults taking vitamin B6 supplements for several months.

Bibliography

Derakhshanfar H, Amree AH, Alimohammadi H, et al. Results of double blind placebo controlled trial to assess the effect of vitamin B6 on managing of nausea and vomiting in pediatrics with acute gastroenteritis. Glob J Health Sci . 2013;5:197–201.

Salam RA, Zuberi NF, Bhutta ZA. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6 ) supplementation during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015;(6) [CD000179].

Ueland PM, Ulvik A, Rios-Avila L, et al. Direct and functional biomarkers of vitamin B6 status. Annu Rev Nutr . 2015;35:33–70.

Biotin

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Biotin (vitamin B7 or vitamin H) functions as a cofactor for enzymes involved in carboxylation reactions within and outside mitochondria. These biotin-dependent carboxylases catalyze key reactions in gluconeogenesis, fatty acid metabolism, and amino acid catabolism.

There is limited information on the biotin content of foods; biotin is believed to be widely distributed, making a deficiency unlikely. Avidin found in raw egg whites acts as a biotin antagonist. Signs of biotin deficiency have been demonstrated in persons who consume large amounts of raw egg whites over long periods. Deficiency also has been described in infants and children receiving enteral and parenteral nutrition formula that lack biotin. Treatment with valproic acid may result in a low biotinidase activity and/or biotin deficiency.

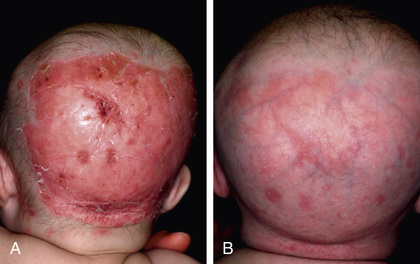

The clinical findings of biotin deficiency include scaly periorificial dermatitis, conjunctivitis, thinning of hair, and alopecia (Fig. 62.5 ). Central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities seen with biotin deficiency are lethargy, hypotonia, seizures, ataxia, and withdrawn behavior. Biotin deficiency can be successfully treated using 1-10 mg of biotin orally daily. The adequate dietary intake values for biotin are 5 µg/day for ages 0-6 mo, 6 µg/day for 7-12 mo, 8 µg/day for 1-3 yr, 12 µg/day for 4-8 yr, 20 µg/day for 9-13 yr, and 25 µg/day for 14-18 yr. No toxic effects have been reported with very high doses.

Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease or biotin and thiamine–responsive basal ganglia disease is a rare childhood neurologic disorder characterized by encephalopathy, seizures, extrapyramidal manifestations, altered signals in basal ganglia (bilateral involvement of caudate nuclei and putamen with sparing of globus pallidus) on MRI, and homozygous missense mutation in the SLC19A3 gene. Chapter 103 describes conditions involving deficiencies in the enzymes holocarboxylase synthetase and biotinidase that respond to treatment with biotin.

Bibliography

Alfadhel M, Almuntashri M, Jadah RH, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease should be renamed biotin-thiamine-responsive basal ganglia disease: a retrospective review of the clinical, radiological and molecular findings of 18 new cases. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2013;8:83.

Ito T, Nishie W, Fujita Y, et al. Infantile eczema caused by formula milk. Lancet . 2013;381:1958.

Kassem H, Wafaie A, Alsuhibani S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease: neuroimaging features before and after treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol . 2014;35:1900–1995.

Tabarki B, Al-Shafi S, Al-Shahwan S, et al. Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease revisited: clinical, radiologic, and genetic findings. Neurology . 2013;80:261–267.

Folate

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

Folate exists in a number of different chemical forms. Folic acid (pteroylglutamic acid) is the synthetic form used in fortified foods and supplements. Naturally occurring folates in foods retain the core chemical structure of pteroylglutamic acid but vary in their state of reduction, the single-carbon moiety they bear, or the length of the glutamate chain. These polyglutamates are broken down and reduced in the small intestine to dihydro- and tetrahydrofolates, which are involved as coenzymes in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism as acceptors and donors of 1-carbon units. Folate is important for CNS development during embryogenesis.

Rice and cereals are rich dietary sources of folate, especially if enriched. Beans, leafy vegetables, and fruits such as oranges and papaya are good sources as well. The vitamin is readily absorbed from the small intestine and is broken down to monoglutamate derivatives by mucosal polyglutamate hydrolases. A high-affinity proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) seems to be essential for absorption of folate in intestine and in various cell types at low pH. The vitamin is also synthesized by colonic bacteria, and its half-life is prolonged by enterohepatic recirculation.

Folate Deficiency

Because of folate's role in protein, DNA, and RNA synthesis, the risk of deficiency is increased during periods of rapid growth or increased cellular metabolism. Folate deficiency can result from poor nutrient content in diet, inadequate absorption (celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease), increased requirement (sickle cell anemia, psoriasis, malignancies, periods of rapid growth as in infancy and adolescence), or inadequate utilization (long-term treatment with high-dose nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; anticonvulsants such as phenytoin and phenobarbital; methotrexate). Rare causes of deficiency are hereditary folate malabsorption, inborn errors of folate metabolism (methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, methionine synthase reductase, and glutamate formiminotransferase deficiencies), and cerebral folate deficiency. A loss-of-function mutation in the gene coding for PCFT is the molecular basis for hereditary folate malabsorption. A high-affinity blocking autoantibody against the membrane-bound folate receptor in the choroid plexus preventing its transport across the blood-brain barrier is the likely cause of the infantile cerebral folate deficiency.

Clinical Manifestations

Folic acid deficiency results in megaloblastic anemia and hypersegmentation of neutrophils. Nonhematologic manifestations include glossitis, listlessness, and growth retardation not related to anemia. An association exists between low maternal folic acid status and neural tube defects , primarily spina bifida and anencephaly, and the role of periconceptional folic acid in their prevention is well established (see Chapter 481.1 ).

Hereditary folate malabsorption manifests at 1-3 mo of age with recurrent or chronic diarrhea, failure to thrive (malnutrition), oral ulcerations, neurologic deterioration, megaloblastic anemia, and opportunistic infections. Cerebral folate deficiency manifests at 4-6 mo of age with irritability, microcephaly, developmental delay, cerebellar ataxia, pyramidal tract signs, choreoathetosis, ballismus, seizures, and blindness as a result of optic atrophy. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate levels are normal in serum and red blood cells (RBCs) but greatly depressed in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of folic acid deficiency anemia is made in the presence of macrocytosis along with low folate levels in serum or RBCs. Normal serum folic acid levels are 5-20 ng/mL; with deficiency, levels are <3 ng/mL. Levels of RBC folate are a better indicator of chronic deficiency. The normal RBC folate level is 150-600 ng/mL of packed cells. The bone marrow is hypercellular because of erythroid hyperplasia, and megaloblastic changes are prominent. Large, abnormal neutrophilic forms (giant metamyelocytes) with cytoplasmic vacuolation also are seen.

Cerebral folate deficiency is associated with low levels of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in CSF and normal folate levels in the plasma and RBCs. Mutations in the PCFT gene are demonstrated in the hereditary folate malabsorption.

Prevention

Breastfed infants have better folate nutrition than nonbreastfed infants throughout infancy. Consumption of folate-rich foods and food fortification programs are important to ensure adequate intake in children and in women of childbearing age. The DRIs for folate are 65 µg of dietary folate equivalents (DFE) for infants 0-6 mo of age and 80 µg of DFE for infants 6-12 mo. (1 DFE = 1 µg food folate = 0.6 µg of folate from fortified food or as a supplement consumed with food = 0.5 µg of a supplement taken on an empty stomach.) For older children, the DRIs are 150 µg of DFE for ages 1-3 yr; 200 µg DFE for 4-8 yr; 300 µg DFE for 9-13 yr; and 400 µg DFE for 14-18 yr. All women desirous of becoming pregnant should consume 400-800 µg folic acid daily; the dose is 4 mg/day in those having delivered a child with neural tube defect. To be effective, supplementation should be started at least 1 mo before conception and continued through the 1st 2-3 mo of pregnancy. The benefit of periconceptional folate supplementation in prevention of congenital heart defects, orofacial clefts, and autistic spectrum disorders is unclear. Preconceptional folate supplementation continued throughout pregnancy may marginally reduce the risk of delivering a small-for-gestational-age infant. Providing iron and folic acid tablets for prevention of anemia in children and pregnant women is a routine strategy in at-risk populations. Mandatory fortification of cereal flours with folic acid coupled with health-education programs has been associated with a substantial reduction in incidence of neural tube defects in many countries.

Treatment

When the diagnosis of folate deficiency is established, folic acid may be administered orally or parenterally at 0.5-1.0 mg/day. Folic acid therapy should be continued for 3-4 wk or until a definite hematologic response has occurred. Maintenance therapy with 0.2 mg of folate is adequate. Prolonged treatment with oral folinic acid is required in cerebral folate deficiency, and the response may be incomplete. High-dose intravenous folinic acid may help in refractory cases. Treatment of hereditary folate malabsorption may be possible with intramuscular folinic acid; some patients may respond to high-dose oral folinic acid therapy.

Folate Toxicity

No adverse effects have been associated with consumption of the amounts of folate normally found in fortified foods. Excessive intake of folate supplements might obscure and potentially delay the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency. Massive doses given by injection have the potential to cause neurotoxicity.

Bibliography

De-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, et al. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015;(12) [CD007950].

Gildestad T, Bjørge T, Vollset SE, et al. Folic acid supplements and risk for oral clefts in the newborn: a population-based study. Br J Nutr . 2015;114:1456–1463.

Hodgetts VA, Morris RK, Francis A, et al. Effectiveness of folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on reducing the risk of small-for-gestational age neonates: a population study, systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG . 2015;4:478–490.

Pfeiffer CM, Sternberg MR, Fazili Z, et al. Folate status and concentrations of serum folate forms in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2. Br J Nutr . 2015;113:1965–1977.

Surén P, Roth C, Bresnahan M, et al. Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. JAMA . 2013;309:570–577.

Williams J, Mai CT, Mulinare J, et al. Updated estimates of neural tube defects prevented by mandatory folic acid fortification—United States, 1995–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2015;64:1–5.

Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin)

H.P.S. Sachdev, Dheeraj Shah

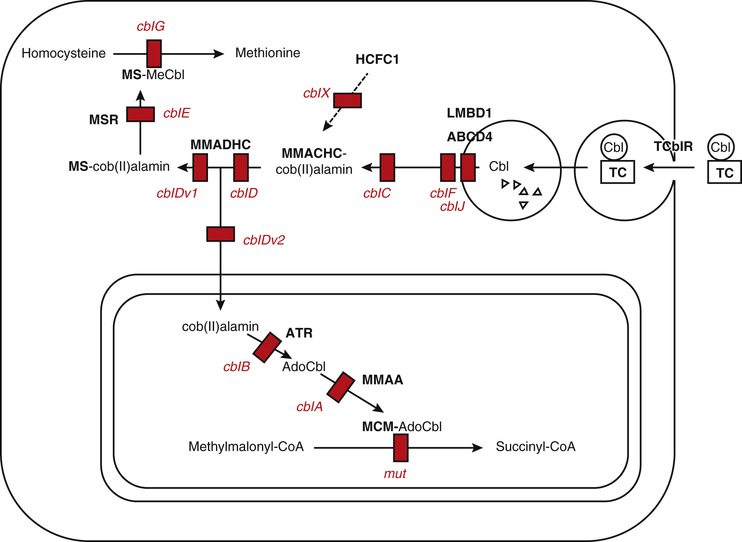

Vitamin B12 , in the form of deoxyadenosylcobalamin, functions as a cofactor for isomerization of methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, an essential reaction in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism. Methylcobalamin is another circulating form of vitamin B12 and is essential for methyl group transfer during the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. This reaction also requires a folic acid cofactor and is important for protein and nucleic acid biosynthesis. Vitamin B12 is important for hematopoiesis, CNS myelination, and mental and psychomotor development (Fig. 62.6 ).

Dietary sources of vitamin B12 are almost exclusively from animal foods. Organ meats, muscle meats, seafood (mollusks, oysters, fish), poultry, and egg yolk are rich sources. Fortified ready-to-eat cereals and milk and their products are the important sources of the vitamin for vegetarians. Human milk is an adequate source for breastfeeding infants if the maternal serum B12 levels are adequate. Vitamin B12 is absorbed from ileum at alkaline pH after binding with intrinsic factor. Enterohepatic circulation, direct absorption, and synthesis by intestinal bacteria are additional mechanisms helping to maintain the vitamin B12 nutriture.

Vitamin B12 Deficiency

Deficiency of vitamin B12 caused by inadequate dietary intake occurs primarily in persons consuming strict vegetarian or vegan diets. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is high in predominantly vegetarian or lactovegetarian populations. Breastfeeding infants of B12 -deficient mothers are also at risk for significant deficiency. Malabsorption of B12 occurs in celiac disease, ileal resections, Crohn disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, and autoimmune atrophic gastritis (pernicious anemia). Use of metformin, proton pump inhibitors, and histamine (H2 ) receptor antagonists may increase the risk of deficiency. Hereditary intrinsic factor deficiency and Imerslund-Gräsbeck disease are inborn errors of metabolism leading to vitamin B12 malabsorption. Mutations in the hereditary intrinsic factor gene cause hereditary intrinsic factor deficiency, whereas mutations in any of the 2 subunits (cubilin and amnionless) of the intrinsic factor receptor cause Imerslund-Gräsbeck disease.

Clinical Manifestations

The hematologic manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency are similar to manifestations of folate deficiency and are discussed in Chapter 481.2 . Irritability, hypotonia, developmental delay, developmental regression, and involuntary movements (predominantly coarse tremors) are the common neurologic symptoms in infants. Older children with vitamin B12 deficiency may show poor growth and poor school performance, whereas sensory deficits, paresthesias, peripheral neuritis, and psychosis are seen in adults. Hyperpigmentation of the knuckles and palms is another common observation with B12 deficiency in children (Fig. 62.7 ). Maternal B12 deficiency may also be an independent risk factor for fetal neural tube defects.

Diagnosis

See Chapter 481.2 .

Treatment

The hematologic symptoms respond promptly to parenteral administration of 250-1,000 µg vitamin B12 . Children with severe deficiency and those with neurologic symptoms need repeated doses, daily or on alternate days in first week, followed by weekly for the 1st 1-2 mo and then monthly. Children having only hematologic presentation recover fully within 2-3 mo, whereas those with neurologic disease need at least 6 mo of therapy. Children with a continuing malabsorptive state and those with inborn errors of vitamin B12 malabsorption need lifelong treatment. Prolonged daily treatment with high-dose (1,000-2,000 µg) oral vitamin B12 preparations is also equally effective in achieving hematologic and neurologic responses in elderly patients, but the data are inadequate in children and young adults.

Prevention

Vitamin B12 DRIs are 0.4 µg/day at age 0-6 mo, 0.5 µg/day at 6-12 mo, 0.9 µg/day at 1-3 yr, 1.2 µg/day at 4-8 yr, 1.8 µg/day at 9-13 yr, 2.4 µg/day at 14-18 yr and in adults, 2.6 µg/day in pregnancy, and 2.8 µg/day in lactation. Pregnant and breastfeeding women should ensure an adequate consumption of animal products to prevent cobalamin deficiency in infants. Strict vegetarians, especially vegans, should ensure regular consumption of vitamin B12 . Food fortification with the vitamin helps to prevent deficiency in predominantly vegetarian populations.

Bibliography

Bahadir A, Reis PG, Erduran E. Oral vitamin B12 treatment is effective for children with nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency. J Paediatr Child Health . 2014;50:721–725.

Benson J, Phillips C, Kay M, et al. Low vitamin B12 levels among newly-arrived refugees from Bhutan, Iran and Afghanistan: a multicentre Australian study. PLoS ONE . 2013;8:e57998.

Berry N, Sagar R, Tripathi BM. Catatonia and other psychiatric symptoms with vitamin B12 deficiency. Acta Psychiatr Scand . 2003;108:156–159.

Cuffe K, Stauffer W, Painter J, et al. Update: Vitamin B12 deficiency among Bhutanese refugees resettling in the United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2014;63:607.

Demir N, Doğan M, Koç A, et al. Dermatological findings of vitamin B12 deficiency and resolving time of these symptoms. Cutan Ocul Toxicol . 2014;33:70–73.

Duong MC, Mora-Plazas M, Marín C, et al. Vitamin B-12 deficiency in children is associated with grade repetition and school absenteeism, independent of folate, iron, zinc, or vitamin A status biomarkers. J Nutr . 2015;145:1541–1548.

Goraya JS, Kaur S, Mehra B. Neurology of nutritional vitamin B12 deficiency in infants: case series from India and literature review. J Child Neurol . 2015;30:1831–1837.

Hannibal L, Lysne V, Bjorke-Monsen AL, et al. Biomarkers and algorithms for the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency. Frontiers Mol Biosci . 2016;3(27):1–16.

Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ . 2014;349:g5226.

Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, et al. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. JAMA . 2013;310:2435–2442.

Kvestad I, Taneja S, Kumar T, et al. Vitamin B12 and folic acid improve gross motor and problem-solving skills in young north Indian children: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE . 2015;10:e0129915.

Pawlak R, Parrott SJ, Raj S, et al. How prevalent is vitamin B(12) deficiency among vegetarians? Nutr Rev . 2013;71:110–117.

Pawlak R, Lester SE, Babatunde T. The prevalence of cobalamin deficiency among vegetarians assessed by serum vitamin B12 : a review of literature. Eur J Clin Nutr . 2014;68:541–548.

Rahmandar MH, Bawcom A, Romano ME, Hamid R. Cobalamin C deficiency in an adolescent with altered mental status and anorexia. Pediatrics . 2014;134(6):e1709–e1714.

Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Engl J Med . 2013;368:149–160.

Strand TA, Taneja S, Ueland PM, et al. Cobalamin and folate status predicts mental development scores in North Indian children 12-18 mo of age. Am J Clin Nutr . 2013;97:310–317.

Torsvik IK, Ueland PM, Markestad T, et al. Motor development related to duration of exclusive breastfeeding, B vitamin status and B12 supplementation in infants with a birth weight between 2000-3000 g, results from a randomized intervention trial. BMC Pediatr . 2015;15:218.

Wang ZP, Shang XX, Zhao ZT. Low maternal vitamin B(12) is a risk factor for neural tube defects: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med . 2012;25:389–394.