Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (Progeria)

Leslie B. Gordon

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), or progeria, is a rare, fatal, autosomal dominant segmental premature aging disease. With an estimated incidence of 1 in 4 million live births and prevalence of 1 in 20 million living individuals, there are an estimated total of 400 children living with progeria in 2018 worldwide. There is no gender, ethnic, or regional bias.

Progeria is caused by a single-base mutation in the LMNA gene, which results in the production of a mutant lamin A protein called progerin . Lamin A is an intermediate filament inner nuclear membrane protein found in most differentiated cells of the body. Without progerin-specific treatment, children with progeria develop premature progressive atherosclerosis and die of heart failure, usually between ages 5 and 20 yr. Progerin is found in increased concentration in skin and the vascular wall of normal older individuals compared to younger individuals, suggesting a role in normal aging.

Clinical Manifestations

Children develop the appearance of accelerated aging, but both clinical and biologic overlaps with aging are segmental, or partial. Physical appearance changes dramatically each year that they age (Fig. 109.1 ). The descriptions discussed next are roughly in order of clinical appearance.

Dermatologic Changes

Skin findings are often apparent as initial signs of progeria. These are variable in severity and include areas of discoloration, stippled pigmentation, tightened areas that can restrict movement, and areas of the trunk or legs where small (1-2 cm), soft, bulging skin is present. Although usually born with normal hair presence, cranial hair is lost within the first few years, leaving soft, downy, sparse immature hair on the scalp, no eyebrows, and scant eyelashes. Nail dystrophy occurs later in life.

Failure to Thrive

Children with progeria experience apparently normal fetal and early postnatal development. Between several months and 1 yr of age, abnormalities in growth and body composition are readily apparent. Severe failure to thrive ensues, heralding generalized lipoatrophy, with apparent wasting of limbs, circumoral cyanosis, and prominent veins around the scalp, neck, and trunk. The mean weight percentile is usually normal at birth, but decreases to below the 3rd percentile despite adequate caloric intake for normal growth and normal resting energy expenditure. A review of 35 children showed an average weight increase of only 0.44 kg/yr, beginning at 24 mo of age and persisting through life. There is interpatient variation in weight gain, but the projected weight gain over time in individual patients is constant, linear, and very predictable; this sharply contrasts with the parabolic growth pattern for normal age- and gender-matched children. Children reach an average final height of approximately 1 meter and weight of approximately 15 kg. Head circumference is normal. The weight deficit is more pronounced than the height deficit and, associated with the loss of subcutaneous fat, results in the emaciated appearance characteristic of progeria. Clinical problems caused by the lack of subcutaneous fat include sensitivity to cold temperatures and foot discomfort caused by lack of fat cushioning. Overt diabetes is very unusual in progeria, but about 30–40% of children have insulin resistance.

Ocular Abnormalities

Ophthalmic signs and symptoms are caused in part by tightened skin and a paucity of subcutaneous fat around the eyes. Children often experience hyperopia and signs of ocular surface disease from nocturnal lagophthalmos and exposure keratopathy, which in turn may lead to corneal ulceration and scarring. Some degree of photophobia is common. Most patients have relatively good acuity; however, advanced ophthalmic disease can be associated with reduced acuity. Children with progeria should have an ophthalmic evaluation at diagnosis and at least yearly thereafter. Aggressive ocular surface lubrication is recommended, including the use of tape tarsorrhaphy at night.

Craniofacial and Dental Phenotypes

Children develop craniofacial disproportion, with micrognathia and retrognathia caused by mandibular hypoplasia. Typical oral and dental manifestations include hypodontia, delayed tooth eruption, severe dental crowding, ogival palatal arch, ankyloglossia, presence of median sagittal palatal fissure, and generalized gingival recession. Eruption may be delayed for many months, and primary teeth may persist for the duration of life. Secondary teeth are present but may or may not erupt. They sometimes erupt on the lingual and palatal surfaces of the mandibular and maxillary alveolar ridges, rather than in place of the primary incisors. In some, but not all cases, extracting primary teeth promotes movement of secondary teeth into place.

Bone and Cartilaginous Abnormalities

Development of bone structure and bone density represents a unique skeletal dysplasia that is not based in malnutrition. Acroosteolysis of the distal phalanges, distal clavicular resorption, and thin, tapered ribs are early signs of progeria (as early as 3 mo of age). Facial disproportion a narrowed nasal bridge and retrognathia makes intubation extremely difficult, and fiberoptic intubation is recommended. A pyriform chest structure and small clavicles can lead to reducible glenohumeral joint instability. Growth of the spine and bony pelvis are normal. However, dysplastic growth of the femoral head and neck axis result in coxa valgus (i.e., straightening of the femoral head-neck axis >125 degrees) and coxa magna, where the diameter of the femoral head is disproportionately large for the acetabulum, resulting in hip instability. The resulting hip dysplasia can be progressive and may result in osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, hip dislocation, and inability to bear weight. Other changes to the appendicular skeleton include flaring of the humeral and femoral metaphyses and constriction of the radial neck. Growth plate morphology is generally normal but can be variable within a single radiograph. The appearance of ossification centers used to define bone age is normal. Bone structure assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) of the radius demonstrates distinct and severe abnormalities in bone structural geometry, consistent with progeria representing a skeletal dysplasia. Areal bone mineral density (aBMD) z scores measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) adjusted for height-age, and true (volumetric) BMD assessed by pQCT are normal to mildly reduced, refuting the assumption that patients with progeria are osteoporotic. Fracture rates in progeria are normal and not associated with fragility fractures observed in other pediatric metabolic bone diseases, such as osteogenesis imperfecta.

Contractures in multiple joints (e.g., fingers, elbows, hips, knees, ankles) may be present at birth and may progress with age because of changes in the laxity of the surrounding soft tissue structures (joint capsule, ligament, skin). Along with irregularities in the congruency of articulating joint surfaces, these changes serve to limit joint motion and affect the pattern of gait. Physical therapy is recommended routinely and throughout life to maximize joint function.

Hearing

Low-tone conductive hearing loss is pervasive in progeria and indicative of a stiff tympanic membrane and/or deficits in the middle ear bony and ligamentous structures. Overall, this does not affect ability to hear the usual spoken tones, but preferential classroom seating is recommended, with annual hearing examinations.

Cardiovascular Disease

Approximately 80% of progeria deaths are caused by heart failure, possibly precipitated by events such as superimposed respiratory infection or surgical intervention. Progeria is a primary vasculopathy characterized by pervasive accelerated vascular stiffening, followed by large- and small-vessel occlusive disease from atherosclerotic plaque formation, with valvular and cardiac insufficiency in later years. Hypertension, angina, cardiomegaly, metabolic syndrome, and congestive heart failure are common end-stage events.

A study of transthoracic echocardiography in treatment-naïve patients revealed diastolic left ventricular dysfunction associated with age-related decline in lateral and septal early (E′) diastolic tissue Doppler velocity z scores and an increase in the ratio of mitral inflow (E) to lateral and septal E’ velocity z scores. Other echocardiographic findings included left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and mitral or aortic valve disease. These tend to appear later in life. Routine carotid ultrasound for plaque monitoring, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWVcf ) measures for vascular stiffening, and echocardiography are recommended.

Cerebrovascular Arteriopathy and Stroke

Cerebral infarction may occur while the child exhibits a normal electrocardiogram. The earliest incidence of stroke occurred at age 0.4 yr. More often strokes occur in the later years. Over the life span, MRI evidence of infarction can be found in 60% of progeria patients, with half of these clinically silent. Both large- and small-vessel disease is found; collateral vessel formation is extensive. Carotid artery blockages are well documented, but infarction can occur even in their absence. A propensity for strokes and an underlying stiff vasculature make maintaining adequate blood pressure through hydration (habitually drinking well) a priority in progeria patients; special care should be taken when considering maintenance of consistent blood pressure during general anesthesia, airplane trips, and hot weather. In addition, 15% of deaths in children with progeria occur from head injury or trauma, including subdural hematoma. This implies an underlying susceptibility to subdural hematoma.

Sexual Development

Females with progeria can develop Tanner Stage II secondary sexual characteristics, including signs of early breast development and sparse pubic hair. They do not achieve Tanner Stage III. Despite minimal to no physical signs of pubertal development and minimal body fat, over half of females experience spontaneous menarche at a median age of 14 yr. Those experiencing menarche vs nonmenstruating females have similar body mass indices, percentage body fat, and serum leptin levels, all of which are vastly below the healthy adolescent population. If bleeding becomes severe, the complete blood count may be decreased, and an oral contraceptive may be used to decrease bleeding severity. Secondary sexual characteristics in males have not been studied. There are no documented cases of reproductive capacity in females or males with progeria.

Normally Functioning Systems

Liver, kidney, thyroid, immune, gastrointestinal, and neurologic systems (other than stroke related) remain intact. Intellect is normal for age, possibly in part from downregulation of progerin expression in the brain by a brain-specific micro-RNA, miRNA-9.

Laboratory Findings

The most consistent laboratory findings are low serum leptin below detectable levels (>90%) and insulin resistance (60%). Platelet count is often moderately high. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and adiponectin concentrations decrease with increasing age to values significantly below normal. Otherwise, lipid panels, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, blood chemistries, liver and kidney function tests, endocrine test, and coagulation tests are generally normal.

Molecular Pathogenesis

Mutations in the LMNA gene cause progeria. The normal LMNA/C gene encodes the proteins lamins A and C, of which only lamin A is associated with human diseases. The lamin proteins are the principal proteins of the nuclear lamina, a complex molecular interface located between the inner membrane of the nuclear envelope and chromatin. The integrity of the lamina is central to many cellular functions, creating and maintaining structural integrity of the nuclear scaffold, DNA replication, RNA transcription, organization of the nucleus, nuclear pore assembly, chromatin function, cell cycling, senescence, and apoptosis.

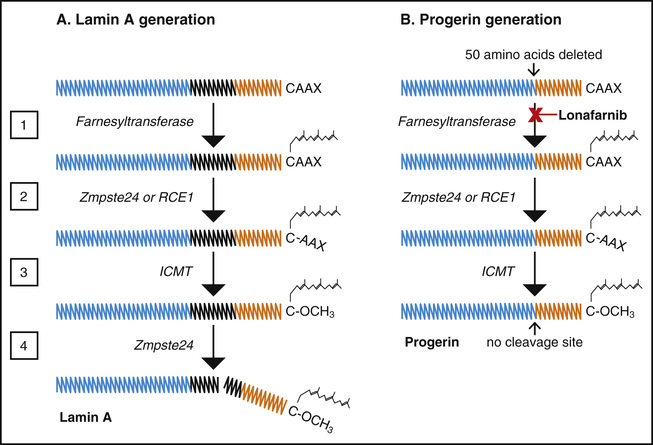

Progeria is almost always a sporadic autosomal dominant disease. There are 2 documented sibling occurrences, both presumably stemming from parental mosaicism, where 1 phenotypically normal parent has germline mosaicism. It is caused by the accelerated use of an alternative, internal splice site that results in the deletion of 150 base pairs in the 3′ portion of exon 11 of the LMNA gene. In about 90% of cases, this results from a single C to T transition at nucleotide 1824 that is silent (Gly608Gly) but optimizes an internal splice site within exon 11. The remaining 10% of cases possess 1 of several single-base mutations within the intron 11 splice donor site, thus reducing specificity for this site and altering the splicing balance in favor of the internal splice. Subsequent to all these mutations, translation followed by posttranslational processing of the altered mRNA produces progerin, a shortened abnormal lamin A protein with a 50–amino acid deletion near its C-terminal end. An understanding of the posttranslational processing pathway and how it is altered to create progerin has led to a number of treatment prospects for the disease (Fig. 109.2 ).

Both lamin A and progerin possess a methylated farnesyl side group attached during posttranslational processing. This is a lipophilic moiety that facilitates intercalation of proteins into the inner nuclear membrane, where most of the lamin and progerin functions are performed. For normal lamin A, loss of the methylated farnesyl anchor releases prelamin from the nuclear membrane, rendering it soluble for autophagic degradation. However, progerin retains its farnesyl moiety. It remains anchored to the membrane, binding other proteins, causing blebbing of the nucleus, disrupting mitosis, and altering gene expression. Progerin also retains a methyl moiety.

Disease in progeria is produced by a dominant negative mechanism; the action of progerin, not the diminution of lamin A, causes the disease phenotype. The severity of disease is determined in part by progerin levels, which are regulated by the particular mutation, tissue type, or other factors influencing use of the internal splice site.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Overall, the constellation of small body habitus, bone, hair, subcutaneous fat, and skin changes results in the marked physical resemblance among patients with progeria (Fig. 109.3 ). For this reason, clinical diagnosis can be achieved or excluded with relative confidence even at young ages, even though there have been a few cases of low–progerin-expressing patients with extremely mild signs. Clinical suspicion should be followed by LMNA genetic sequence testing. The disorders that resemble progeria are those grouped as the senile-like syndromes and include Wiedmann-Rautenstrauch syndrome, Werner syndrome, Cockayne syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, restrictive dermopathy, and Nestor-Guillermo progeria syndrome (Table 109.1 ). Patients often fall under none of these diagnoses and represent ultra-rare, unnamed progeroid laminopathies that carry either non–progerin-producing mutations in LMNA or the lamin-associated enzyme (ZMPSTE24) , or progeroid syndromes without lamin-associated mutations.

Table 109.1

Features of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome and Other Disorders With Overlapping Features

| HUTCHINSON-GILFORD PROGERIA SYNDROME | WIEDEMANN-RAUTENSTRAUCH SYNDROME | WERNER SYNDROME | COCKAYNE SYNDROME | ROTHMUND-THOMPSON SYNDROME | RESTRICTIVE DERMOPATHY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causative gene(s) | LMNA | Unknown | WRN , LMNA |

CSA (ERCC8) CSB (ERCC6) |

RECQL4 | ZMPSTE24, LMNA |

| Inheritance | Autosomal Dominant | Unknown, likely recessive | Recessive | Recessive | Recessive | Recessive |

| Onset | Infancy | Newborn | Young adult | Newborn/infancy | Infancy | Newborn |

| Growth retardation | Postnatal | Intrauterine | Onset after puberty | Postnatal | Postnatal | Intrauterine |

| Hair loss | + Total | + Scalp patchy | + Scalp, sparse, graying | − | + Diffuse | + Diffuse |

| Skin abnormalities | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Subcutaneous fat loss | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Skin calcification | + Rarely | − | + | − | − | − |

| Short stature | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Coxa valga | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Acroosteolysis | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Mandibular dysplasia | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| Osteopenia | + Mild | + | + | − | + | + |

| Vasculopathy | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Heart failure | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Strokes | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Insulin Resistance | + | − | + Rarely | − | − | − |

| Diabetes | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Hypogonadism | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Dental abnormality | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Voice abnormality | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Hearing loss | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Joint contractures | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| Hyperkeratosis | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Cataracts | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| Tumor predisposition | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Intellectual disability | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Neurologic disorder | − | + | + Mild | + | − | − |

Adapted from Hegele RA: Drawing the line in Progeria syndromes, Lancet 362;416–417, 2003.

Treatment and Prognosis

Children with progeria develop a severe premature form of atherosclerosis. Prior to death, cardiac decline with left-sided hypertrophy, valvular insufficiency, and pulmonary edema develop; neurovascular decline with transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), strokes, and occasionally seizures can result in significant morbidity. Death occurs generally between ages 5 and 20 yr, with a median life span of 14.5 yr, resulting from heart failure, sometimes with superimposed respiratory infection (approximately 80%); from head injury or trauma, including subdural hematoma (approximately 15%); and rarely from stroke (1–3%) or complications from anesthesia during surgery (1–3%).

Growth hormone , 0.05 mg/kg/day subcutaneously, has resulted in increased rate of weight gain and overall size, but still well below that seen in normal children. Low-dose aspirin therapy is recommended at 2 mg/kg/day, as an extension of what is known about decreasing cardiovascular risk in the general at-risk adult population. It is not known whether growth hormone or low-dose aspirin has any effect on morbidity or mortality.

Several clinical treatment trials have been based on medications that target the posttranslational pathway of progerin (see Fig. 109.2 ). Inhibiting posttranslational progerin farnesylation is aimed at preventing this disease-causing protein from anchoring to the nuclear membrane, where it carries out much of its damage. A prospective single-arm clinical trial was conducted with the farnesyltransferase inhibitor lonafarnib (NCT00425607). Lonafarnib was well tolerated; the most common side effects were diarrhea, nausea, and loss of appetite, which generally improved with time. Subgroups of patients experienced increased rate of weight gain, decreased vascular stiffness measured by decreased PWVcf and carotid artery echodensity, improved left ventricular diastolic function, increased radial bone structural rigidity, improved sensorineural hearing, and early evidence of decreased headache, TIA, and stroke rates. Dermatologic, dental, joint contracture, insulin resistance, lipodystrophy, BMD, and joint contractures were unaffected by drug treatment. A lonafarnib extension study was initiated, which added 30 children to the study. Children treated with lonafarnib demonstrated an increase in estimated survival over untreated children with progeria.

A clinical trial that added pravastatin (FDA approved to lower cholesterol) and zoledronate (FDA approved for osteoporosis) to the lonafarnib regimen was similarly aimed at inhibiting progerin farnesylation (NCT00916747), but results showed no detected improvements in clinical status over lonafarnib monotherapy. An ongoing clinical trial adding everolimus (FDA-approved mTOR inhibitor) to the lonafarnib regimen is aimed at accelerating autophagy of progerin, thus theoretically reducing its accumulation and cellular damage (NCT02579044). Results of this study are forthcoming.

Patient Resources

The Progeria Research Foundation (www.progeriaresearch.org ) maintains an international progeria patient registry, provides a diagnostics program and complete patient care manual, and coordinates clinical treatment trials. It funds preclinical and clinical research to define the molecular basis of the disorder and to discover treatments and a cure. The Foundation website is an excellent source of current information on progeria for families of children with the disorder, their physicians, and interested scientists. Additional resources include the National Human Genome Research Institute (www.genome.gov/11007255/ ), National Center for Biotechnology Information Genereviews (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1121/ ), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (www.rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7467/progeria ).