Polioviruses

Eric A.F. Simões

Etiology

The polioviruses are nonenveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the Picornaviridae family, in the genus Enterovirus, species Enterovirus C and consist of 3 antigenically distinct serotypes (types 1, 2, and 3). Polioviruses spread from the intestinal tract to the central nervous system (CNS), where they cause aseptic meningitis and poliomyelitis, or polio. The polioviruses are extremely hardy and can retain infectivity for several days at room temperature.

Epidemiology

The most devastating result of poliovirus infection is paralysis, although 90–95% of infections are inapparent. Despite the absence of symptoms, clinically inapparent infections induce protective immunity. Clinically apparent but nonparalytic illness occurs in approximately 5% of all infections, with paralytic polio occurring in approximately 1 in 1,000 infections among infants to approximately 1 in 100 infections among adolescents. In industrialized countries prior to universal vaccination, epidemics of paralytic poliomyelitis occurred primarily in adolescents. Conversely, in developing countries with poor sanitation, infection early in life results in infantile paralysis. Improved sanitation explains the virtual eradication of polio from the United States in the early 1960s, when only approximately 65% of the population was immunized with the Salk vaccine, which contributed to the disappearance of circulating wild-type poliovirus in the United States and Europe.

Transmission

Humans are the only known reservoir for the polioviruses, which are spread by the fecal-oral route. Poliovirus has been isolated from feces for longer than 2 wk before paralysis to several wk after the onset of symptoms.

Pathogenesis

Polioviruses infect cells by adsorbing to the genetically determined poliovirus receptor (CD155). The virus penetrates the cell, is uncoated, and releases viral RNA. The RNA is translated to produce proteins responsible for replication of the RNA, shutoff of host cell protein synthesis, and synthesis of structural elements that compose the capsid. Mature virus particles are produced in 6-8 hr and are released into the environment by disruption of the cell.

In the contact host, wild-type and vaccine strains of polioviruses gain host entry via the gastrointestinal tract. Recent studies in nonhuman primates demonstrate that the primary sites of replication are in the CD155+ epithelial cells lining the mucosa of the tonsil follicle and small intestine, as well as see the macrophages/dendritic cells in the tonsil follicle and Peyer patches. Regional lymph nodes are infected, and primary viremia occurs after 2-3 days. The virus seeds multiple sites, including the reticuloendothelial system, brown fat deposits, and skeletal muscle. Wild-type poliovirus probably accesses the CNS along peripheral nerves. Vaccine strains of polioviruses do not replicate in the CNS, a feature that accounts for the safety of the live-attenuated vaccine. Occasional revertants (by nucleotide substitution) of these vaccine strains develop a neurovirulent phenotype and cause vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP). Reversion occurs in the small intestine and probably accesses the CNS via the peripheral nerves. Poliovirus has almost never been cultured from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with paralytic disease, and patients with aseptic meningitis caused by poliovirus never have paralytic disease. With the 1st appearance of non-CNS symptoms, a secondary viremia probably occurs as a result of enormous viral replication in the reticuloendothelial system.

The exact mechanism of entry into the CNS is not known. However, once entry is gained, the virus may traverse neural pathways and multiple sites within the CNS are often affected. The effect on motor and vegetative neurons is most striking and correlates with the clinical manifestations. Perineuronal inflammation, a mixed inflammatory reaction with both polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes, is associated with extensive neuronal destruction. Petechial hemorrhages and considerable inflammatory edema also occur in areas of poliovirus infection. The poliovirus primarily infects motor neuron cells in the spinal cord (the anterior horn cells ) and the medulla oblongata (the cranial nerve nuclei). Because of the overlap in muscle innervation by 2-3 adjacent segments of the spinal cord, clinical signs of weakness in the limbs develop when more than 50% of motor neurons are destroyed. In the medulla, less-extensive lesions cause paralysis, and involvement of the reticular formation that contains the vital centers controlling respiration and circulation may have a catastrophic outcome. Involvement of the intermediate and dorsal areas of the horn and the dorsal root ganglia in the spinal cord results in hyperesthesia and myalgias that are typical of acute poliomyelitis. Other neurons affected are the nuclei in the roof and vermis of the cerebellum, the substantia nigra, and, occasionally, the red nucleus in the pons; there may be variable involvement of thalamic, hypothalamic, and pallidal nuclei and the motor cortex.

Apart from the histopathology of the CNS, inflammatory changes occur generally in the reticuloendothelial system. Inflammatory edema and sparse lymphocytic infiltration are prominently associated with hyperplastic lymphocytic follicles.

Infants acquire immunity transplacentally from their mothers. Transplacental immunity disappears at a variable rate during the 1st 4-6 mo of life. Active immunity after natural infection is probably lifelong but protects against the infecting serotype only; infections with other serotypes are possible. Poliovirus-neutralizing antibodies develop within several days after exposure as a result of replication of the virus in the tonsils and in the intestinal tract and deep lymphatic tissues. This early production of circulating immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies protects against CNS invasion. Local (mucosal) immunity, conferred mainly by secretory IgA, is an important defense against subsequent reinfection of the gastrointestinal tract.

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period of poliovirus from contact to initial clinical symptoms is usually considered to be 8-12 days, with a range of 5-35 days. Poliovirus infections with wild-type virus may follow 1 of several courses: inapparent infection, which occurs in 90–95% of cases and causes no disease and no sequelae; abortive poliomyelitis; nonparalytic poliomyelitis; or paralytic poliomyelitis. Paralysis, if it occurs, appears 3-8 days after the initial symptoms. The clinical manifestations of paralytic polio caused by wild or vaccine strains are comparable, although the incidence of abortive and nonparalytic paralysis with vaccine-associated poliomyelitis is unknown.

Abortive Poliomyelitis

In approximately 5% of patients, a nonspecific influenza-like syndrome occurs 1-2 wk after infection, which is termed abortive poliomyelitis . Fever, malaise, anorexia, and headache are prominent features, and there may be sore throat and abdominal or muscular pain. Vomiting occurs irregularly. The illness is short lived, lasting up to 2-3 days. The physical examination may be normal or may reveal nonspecific pharyngitis, abdominal or muscular tenderness, and weakness. Recovery is complete, and no neurologic signs or sequelae develop.

Nonparalytic Poliomyelitis

In approximately 1% of patients infected with wild-type poliovirus, signs of abortive poliomyelitis are present, as are more intense headache, nausea, and vomiting, as well as soreness and stiffness of the posterior muscles of the neck, trunk, and limbs. Fleeting paralysis of the bladder and constipation are frequent. Approximately two thirds of these children have a short symptom-free interlude between the 1st phase (minor illness ) and the 2nd phase (CNS disease or major illness ). Nuchal rigidity and spinal rigidity are the basis for the diagnosis of nonparalytic poliomyelitis during the 2nd phase.

Physical examination reveals nuchal-spinal signs and changes in superficial and deep reflexes. Gentle forward flexion of the occiput and neck elicits nuchal rigidity. The examiner can demonstrate head drop by placing the hands under the patient's shoulders and raising the patient's trunk. Although normally the head follows the plane of the trunk, in poliomyelitis it often falls backward limply, but this response is not attributable to true paresis of the neck flexors. In struggling infants, it may be difficult to distinguish voluntary resistance from clinically important true nuchal rigidity. The examiner may place the infant's shoulders flush with the edge of the table, support the weight of the occiput in the hand, and then flex the head anteriorly. True nuchal rigidity persists during this maneuver. When open, the anterior fontanel may be tense or bulging.

In the early stages the reflexes are normally active and remain so unless paralysis supervenes. Changes in reflexes, either increased or decreased, may precede weakness by 12-24 hr. The superficial reflexes, the cremasteric and abdominal reflexes, and the reflexes of the spinal and gluteal muscles are usually the first to diminish. The spinal and gluteal reflexes may disappear before the abdominal and cremasteric reflexes. Changes in the deep tendon reflexes generally occur 8-24 hr after the superficial reflexes are depressed and indicate impending paresis of the extremities. Tendon reflexes are absent with paralysis. Sensory defects do not occur in poliomyelitis.

Paralytic Poliomyelitis

Paralytic poliomyelitis develops in approximately 0.1% of persons infected with poliovirus, causing 3 clinically recognizable syndromes that represent a continuum of infection differentiated only by the portions of the CNS most severely affected. These are (1) spinal paralytic poliomyelitis, (2) bulbar poliomyelitis, and (3) polioencephalitis.

Spinal paralytic poliomyelitis may occur as the 2nd phase of a biphasic illness, the 1st phase of which corresponds to abortive poliomyelitis. The patient then appears to recover and feels better for 2-5 days, after which severe headache and fever occur with exacerbation of the previous systemic symptoms. Severe muscle pain is present, and sensory and motor phenomena (e.g., paresthesia, hyperesthesia, fasciculations, and spasms) may develop. On physical examination the distribution of paralysis is characteristically spotty. Single muscles, multiple muscles, or groups of muscles may be involved in any pattern. Within 1-2 days, asymmetric flaccid paralysis or paresis occurs . Involvement of 1 leg is most common, followed by involvement of 1 arm. The proximal areas of the extremities tend to be involved to a greater extent than the distal areas. To detect mild muscular weakness, it is often necessary to apply gentle resistance in opposition to the muscle group being tested. Examination at this point may reveal nuchal stiffness or rigidity, muscle tenderness, initially hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (for a short period) followed by absence or diminution of reflexes, and paresis or flaccid paralysis. In the spinal form, there is weakness of some of the muscles of the neck, abdomen, trunk, diaphragm, thorax, or extremities. Sensation is intact; sensory disturbances, if present, suggest a disease other than poliomyelitis.

The paralytic phase of poliomyelitis is extremely variable; some patients progress during observation from paresis to paralysis, whereas others recover, either slowly or rapidly. The extent of paresis or paralysis is directly related to the extent of neuronal involvement; paralysis occurs if >50% of the neurons supplying the muscles are destroyed. The extent of involvement is usually obvious within 2-3 days; only rarely does progression occur beyond this interval. Bowel and bladder dysfunction ranging from transient incontinence to paralysis with constipation and urinary retention often accompany paralysis of the lower limbs.

The onset and course of paralysis are variable in developing countries. The biphasic course is rare; typically the disease manifests in a single phase in which prodromal symptoms and paralysis occur in a continuous fashion. In developing countries, where a history of intramuscular injections precedes paralytic poliomyelitis in approximately 50–60% of patients, patients may present initially with fever and paralysis (provocation paralysis ). The degree and duration of muscle pain are also variable, ranging from a few days usually to a wk. Occasionally, spasm and increased muscle tone with a transient increase in deep tendon reflexes occur in some patients, whereas in most patients, flaccid paralysis occurs abruptly. Once the temperature returns to normal, progression of paralytic manifestations stops. Little recovery from paralysis is noted in the 1st days or wk, but, if it is to occur, it is usually evident within 6 mo. The return of strength and reflexes is slow and may continue to improve for as long as 18 mo after the acute disease. Lack of improvement from paralysis within the 1st several wk or mo after onset is usually evidence of permanent paralysis. Atrophy of the limb, failure of growth, and deformity are common and are especially evident in the growing child.

Bulbar poliomyelitis may occur as a clinical entity without apparent involvement of the spinal cord. Infection is a continuum, and designation of the disease as bulbar implies only dominance of the clinical manifestations by dysfunctions of the cranial nerves and medullary centers. The clinical findings seen with bulbar poliomyelitis with respiratory difficulty (other than paralysis of extraocular, facial, and masticatory muscles) include (1) nasal twang to the voice or cry caused by palatal and pharyngeal weakness (hard-consonant words such as cookie and candy bring this feature out best); (2) inability to swallow smoothly, resulting in accumulation of saliva in the pharynx, indicating partial immobility (holding the larynx lightly and asking the patient to swallow will confirm such immobility); (3) accumulated pharyngeal secretions, which may cause irregular respirations that appear interrupted and abnormal even to the point of falsely simulating intercostal or diaphragmatic weakness; (4) absence of effective coughing, shown by constant fatiguing efforts to clear the throat; (5) nasal regurgitation of saliva and fluids as a result of palatal paralysis, with inability to separate the oropharynx from the nasopharynx during swallowing; (6) deviation of the palate, uvula, or tongue; (7) involvement of vital centers in the medulla, which manifest as irregularities in rate, depth, and rhythm of respiration; as cardiovascular alterations, including blood pressure changes (especially increased blood pressure), alternate flushing and mottling of the skin, and cardiac arrhythmias; and as rapid changes in body temperature; (8) paralysis of 1 or both vocal cords, causing hoarseness, aphonia, and, ultimately, asphyxia unless the problem is recognized on laryngoscopy and managed by immediate tracheostomy; and (9) the rope sign, an acute angulation between the chin and larynx caused by weakness of the hyoid muscles (the hyoid bone is pulled posteriorly, narrowing the hypopharyngeal inlet).

Uncommonly, bulbar disease may culminate in an ascending paralysis (Landry type), in which there is progression cephalad from initial involvement of the lower extremities. Hypertension and other autonomic disturbances are common in bulbar involvement and may persist for a week or more or may be transient. Occasionally, hypertension is followed by hypotension and shock and is associated with irregular or failed respiratory effort, delirium, or coma. This kind of bulbar disease may be rapidly fatal.

The course of bulbar disease is variable; some patients die as a result of extensive, severe involvement of the various centers in the medulla; others recover partially but require ongoing respiratory support, and others recover completely. Cranial nerve involvement is seldom permanent. Atrophy of muscles may be evident, patients immobilized for long periods may experience pneumonia, and renal stones may form as a result of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria secondary to bone resorption.

Polioencephalitis is a rare form of the disease in which higher centers of the brain are severely involved. Seizures, coma, and spastic paralysis with increased reflexes may be observed. Irritability, disorientation, drowsiness, and coarse tremors are often present with peripheral or cranial nerve paralysis that coexists or ensues. Hypoxia and hypercapnia caused by inadequate ventilation due to respiratory insufficiency may produce disorientation without true encephalitis. The manifestations are common to encephalitis of any cause and can be attributed to polioviruses only with specific viral diagnosis or if accompanied by flaccid paralysis.

Paralytic poliomyelitis with ventilatory insufficiency results from several components acting together to produce ventilatory insufficiency resulting in hypoxia and hypercapnia. It may have profound effects on many other systems. Because respiratory insufficiency may develop rapidly, close continued clinical evaluation is essential. Despite weakness of the respiratory muscles, the patient may respond with so much respiratory effort associated with anxiety and fear that overventilation may occur at the outset, resulting in respiratory alkalosis. Such effort is fatiguing and contributes to respiratory failure.

There are certain characteristic patterns of disease. Pure spinal poliomyelitis with respiratory insufficiency involves tightness, weakness, or paralysis of the respiratory muscles (chiefly the diaphragm and intercostals) without discernible clinical involvement of the cranial nerves or vital centers that control respiration, circulation, and body temperature. The cervical and thoracic spinal cord segments are chiefly affected. Pure bulbar poliomyelitis involves paralysis of the motor cranial nerve nuclei with or without involvement of the vital centers. Involvement of the 9th, 10th, and 12th cranial nerves results in paralysis of the pharynx, tongue, and larynx with consequent airway obstruction. Bulbospinal poliomyelitis with respiratory insufficiency affects the respiratory muscles and results in coexisting bulbar paralysis.

The clinical findings associated with involvement of the respiratory muscles include (1) anxious expression; (2) inability to speak without frequent pauses, resulting in short, jerky, breathless sentences; (3) increased respiratory rate; (4) movement of the ala nasi and of the accessory muscles of respiration; (5) inability to cough or sniff with full depth; (6) paradoxical abdominal movements caused by diaphragmatic immobility caused by spasm or weakness of 1 or both leaves; and (7) relative immobility of the intercostal spaces, which may be segmental, unilateral, or bilateral. When the arms are weak, and especially when deltoid paralysis occurs, there may be impending respiratory paralysis because the phrenic nerve nuclei are in adjacent areas of the spinal cord. Observation of the patient's capacity for thoracic breathing while the abdominal muscles are splinted manually indicates minor degrees of paresis. Light manual splinting of the thoracic cage helps to assess the effectiveness of diaphragmatic movement.

Diagnosis

Poliomyelitis should be considered in any unimmunized or incompletely immunized child with paralytic disease. Although this guideline is most applicable in poliomyelitis endemic countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria), the spread of polio in 2013 from endemic countries to many nonendemic countries (Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, and Syria) and the isolation of wild poliovirus type 1 in Israel in 2014 and circulating type 1 vaccine-associated paralytic polio in Ukraine in 2015 suggest that the diagnosis of polio should be entertained in all countries. VAPP should be considered in any child with paralytic disease occurring 7-14 days after receiving the orally administered polio vaccine (OPV). VAPP can occur at later times after administration and should be considered in any child with paralytic disease in countries or regions where wild-type poliovirus has been eradicated and the OPV has been administered to the child or a contact. The combination of fever, headache, neck and back pain, asymmetric flaccid paralysis without sensory loss, and pleocytosis does not regularly occur in any other illness.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the laboratory diagnosis of poliomyelitis be confirmed by isolation and identification of poliovirus in the stool, with specific identification of wild-type and vaccine-type strains. In suspected cases of acute flaccid paralysis, 2 stool specimens should be collected 24-48 hr apart as soon as possible after the diagnosis of poliomyelitis is suspected. Poliovirus concentrations are high in the stool in the 1st wk after the onset of paralysis, which is the optimal time for collection of stool specimens. Polioviruses may be isolated from 80–90% of specimens from acutely ill patients, whereas <20% of specimens from such patients may yield virus within 3-4 wk after onset of paralysis. Because most children with spinal or bulbospinal poliomyelitis have constipation, rectal straws may be used to obtain specimens; ideally a minimum of 8-10 g of stool should be collected. In laboratories that can isolate poliovirus, isolates should be sent to either the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or to 1 of the WHO-certified poliomyelitis laboratories where DNA sequence analysis can be performed to distinguish between wild poliovirus and neurovirulent, revertant OPV strains. With the current WHO plan for global eradication of poliomyelitis, most regions of the world (the Americas, Europe, and Australia) have been certified wild-poliovirus free; in these areas, poliomyelitis is most often caused by vaccine strains. Hence it is critical to differentiate between wild-type and revertant vaccine-type strains.

The CSF is often normal during the minor illness and typically contains a pleocytosis with 20-300 cells/µL with CNS involvement. The cells in the CSF may be polymorphonuclear early during the course of the disease but shift to mononuclear cells soon afterward. By the 2nd wk of major illness, the CSF cell count falls to near-normal values. In contrast, the CSF protein content is normal or only slightly elevated at the outset of CNS disease but usually rises to 50-100 mg/dL by the 2nd wk of illness. In polioencephalitis, the CSF may remain normal or show minor changes. Serologic testing demonstrates seroconversion or a 4-fold or greater increase in antibody titers from the acute phase of illness to 3-6 wk later.

Differential Diagnosis

Poliomyelitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any case of paralysis and is only 1 of many causes of acute flaccid paralysis in children and adults. There are numerous other causes of acute flaccid paralysis (Table 276.1 ). In most conditions, the clinical features are sufficient to differentiate between these various causes, but in some cases nerve conduction studies and electromyograms, in addition to muscle biopsies, may be required.

Table 276.1

Differential Diagnosis of Acute Flaccid Paralysis

| SITE, CONDITION, FACTOR, OR AGENT | CLINICAL FINDINGS | ONSET OF PARALYSIS | PROGRESSION OF PARALYSIS | SENSORY SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | REDUCTION OR ABSENCE OF DEEP TENDON REFLEXES | RESIDUAL PARALYSIS | PLEOCYTOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Horn Cells of Spinal Cord | |||||||

| Poliomyelitis (wild and vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis) | Paralysis | Incubation period 7-14 days (range: 4-35 days) | 24-48 hr to onset of full paralysis; proximal → distal, asymmetric | No | Yes | Yes | Aseptic meningitis (moderate polymorphonuclear leukocytes at 2-3 days) |

| Nonpolio enteroviruses (including EV-A71, EV D68) | Hand-foot-and-mouth disease, aseptic meningitis, acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, possibly idiopathic epidemic flaccid paralysis | As in poliomyelitis | As in poliomyelitis | No | Yes | Yes | As in poliomyelitis |

| West Nile virus | Meningitis encephalitis | As in poliomyelitis | As in poliomyelitis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other Neurotropic Viruses | |||||||

| Rabies virus | Mo–Yr | Acute, symmetric, ascending | Yes | Yes | No | ± | |

| Varicella-zoster virus | Exanthematous vesicular eruptions | Incubation period 10-21 days | Acute, symmetric, ascending | Yes | ± | ± | Yes |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | Incubation period 5-15 days | Acute, proximal, asymmetric | ± | ± | ± | Yes | |

| Guillain-Barré Syndrome | |||||||

| Acute inflammatory polyradiculo-neuropathy | Preceding infection, bilateral facial weakness | Hr to 10 days | Acute, symmetric, ascending (days to 4 wk) | Yes | Yes | ± | No |

| Acute motor axonal neuropathy | Fulminant, widespread paralysis, bilateral facial weakness, tongue involvement | Hr to 10 days | 1-6 days | No | Yes | ± | No |

| Acute Traumatic Sciatic Neuritis | |||||||

| Intramuscular gluteal injection | Acute, asymmetric | Hr to 4 days | Complete, affected limb | Yes | Yes | ± | No |

| Acute transverse myelitis | Preceding Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Schistosoma , other parasitic or viral infection | Acute, symmetric hypotonia of lower limbs | Hr to days | Yes | Yes, early | Yes | Yes |

| Epidural abscess | Headache, back pain, local spinal tenderness, meningismus | Complete | Yes | Yes | ± | Yes | |

| Spinal cord compression; trauma | Complete | Hr to days | Yes | Yes | ± | ± | |

| Neuropathies | |||||||

| Exotoxin of Corynebacterium diphtheriae | In severe cases, palatal paralysis, blurred vision | Incubation period 1-8 wk (paralysis 8-12 wk after onset of illness) | Yes | Yes | ± | ||

| Toxin of Clostridium botulinum | Abdominal pain, diplopia, loss of accommodation, mydriasis | Incubation period 18-36 hr | Rapid, descending, symmetric | ± | No | No | |

| Tick bite paralysis | Ocular symptoms | Latency period 5-10 days | Acute, symmetric, ascending | No | Yes | No | |

| Diseases of the Neuromuscular Junction | |||||||

| Myasthenia gravis | Weakness, fatigability, diplopia, ptosis, dysarthria | Multifocal | No | No | No | No | |

| Disorders of Muscle | |||||||

| Polymyositis | Neoplasm, autoimmune disease | Subacute, proximal → distal | Wk to mo | No | Yes | No | |

| Viral myositis | Pseudoparalysis | Hr to days | No | No | No | ||

| Metabolic Disorders | |||||||

| Hypokalemic periodic paralysis | Proximal limb, respiratory muscles | Sudden postprandial | No | Yes | ± | No | |

| Intensive Care Unit Weakness | |||||||

| Critical illness polyneuropathy | Flaccid limbs and respiratory weakness | Acute, following systemic inflammatory response syndrome/sepsis | Hr to days | ± | Yes | ± | No |

Modified from Marx A, Glass JD, Sutter RW: Differential diagnosis of acute flaccid paralysis and its role in poliomyelitis surveillance, Epidemiol Rev 22:298–316, 2000.

The possibility of polio should be considered in any case of acute flaccid paralysis, even in countries where polio has been eradicated. The diagnoses most often confused with polio are VAPP, West Nile virus infection, and infections caused by other enteroviruses (including EV-A71 and EV-D68), as well as Guillain-Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis, and traumatic paralysis. In Guillain-Barré syndrome , which is the most difficult to distinguish from poliomyelitis, the paralysis is characteristically symmetric, and sensory changes and pyramidal tract signs are common, contrasting with poliomyelitis. Fever, headache, and meningeal signs are less notable, and the CSF has few cells but an elevated protein content. Transverse myelitis progresses rapidly over hr to days, causing an acute symmetric paralysis of the lower limbs with concomitant anesthesia and diminished sensory perception. Autonomic signs of hypothermia in the affected limbs are common, and there is bladder dysfunction. The CSF is usually normal. Traumatic neuritis occurs from a few hr to a few days after the traumatic event, is asymmetric, is acute, and affects only 1 limb. Muscle tone and deep tendon reflexes are reduced or absent in the affected limb with pain in the gluteus. The CSF is normal.

Conditions causing pseudoparalysis do not present with nuchal-spinal rigidity or pleocytosis. These causes include unrecognized trauma, transient (toxic) synovitis, acute osteomyelitis, acute rheumatic fever, scurvy, and congenital syphilis (pseudoparalysis of Parrot).

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment for poliomyelitis. The management is supportive and aimed at limiting progression of disease, preventing ensuing skeletal deformities, and preparing the child and family for the prolonged treatment required and for permanent disability if this seems likely. Patients with the nonparalytic and mildly paralytic forms of poliomyelitis may be treated at home. All intramuscular injections and surgical procedures are contraindicated during the acute phase of the illness, especially in the 1st wk of illness, because they might result in progression of disease.

Abortive Poliomyelitis

Supportive treatment with analgesics, sedatives, an attractive diet, and bed rest until the child's temperature is normal for several days is usually sufficient. Avoidance of exertion for the ensuing 2 wk is desirable, and careful neurologic and musculoskeletal examinations should be performed 2 mo later to detect any minor involvement.

Nonparalytic Poliomyelitis

Treatment for the nonparalytic form is similar to that for the abortive form; in particular, relief is indicated for the discomfort of muscle tightness and spasm of the neck, trunk, and extremities. Analgesics are more effective when they are combined with the application of hot packs for 15-30 min every 2-4 hr. Hot tub baths are sometimes useful. A firm bed is desirable and can be improvised at home by placing table leaves or a sheet of plywood beneath the mattress. A footboard or splint should be used to keep the feet at a right angle to the legs. Because muscular discomfort and spasm may continue for some wk, even in the nonparalytic form, hot packs and gentle physical therapy may be necessary. Patients with nonparalytic poliomyelitis should also be carefully examined 2 mo after apparent recovery to detect minor residual effects that might cause postural problems in later yr.

Paralytic Poliomyelitis

Most patients with the paralytic form of poliomyelitis require hospitalization with complete physical rest in a calm atmosphere for the 1st 2-3 wk. Suitable body alignment is necessary for comfort and to avoid excessive skeletal deformity. A neutral position with the feet at right angles to the legs, the knees slightly flexed, and the hips and spine straight is achieved by use of boards, sandbags, and, occasionally, light splint shells. The position should be changed every 3-6 hr. Active and passive movements are indicated as soon as the pain has disappeared. Moist hot packs may relieve muscle pain and spasm. Opiates and sedatives are permissible only if no impairment of ventilation is present or impending. Constipation is common, and fecal impaction should be prevented. When bladder paralysis occurs, a parasympathetic stimulant such as bethanechol may induce voiding in 15-30 min; some patients show no response to this agent, and others respond with nausea, vomiting, and palpitations. Bladder paresis rarely lasts more than a few days. If bethanechol fails, manual compression of the bladder and the psychologic effect of running water should be tried. If catheterization must be performed, care must be taken to prevent urinary tract infections. An appealing diet and a relatively high fluid intake should be started at once unless the patient is vomiting. Additional salt should be provided if the environmental temperature is high or if the application of hot packs induces sweating. Anorexia is common initially. Adequate dietary and fluid intake can be maintained by placement of a central venous catheter. An orthopedist and a physiatrist should see patients as early in the course of the illness as possible and should assume responsibility for their care before fixed deformities develop.

The management of pure bulbar poliomyelitis consists of maintaining the airway and avoiding all risk of inhalation of saliva, food, and vomitus. Gravity drainage of accumulated secretions is favored by using the head-low (foot of bed elevated 20-25 degrees) prone position with the face to 1 side. Patients with weakness of the muscles of respiration or swallowing should be nursed in a lateral or semiprone position. Aspirators with rigid or semirigid tips are preferred for direct oral and pharyngeal aspiration, and soft, flexible catheters may be used for nasopharyngeal aspiration. Fluid and electrolyte equilibrium is best maintained by intravenous infusion because tube or oral feeding in the 1st few days may incite vomiting. In addition to close observation for respiratory insufficiency, the blood pressure should be measured at least twice daily because hypertension is not uncommon and occasionally leads to hypertensive encephalopathy. Patients with pure bulbar poliomyelitis may require tracheostomy because of vocal cord paralysis or constriction of the hypopharynx; most patients who recover have little residual impairment, although some exhibit mild dysphagia and occasional vocal fatigue with slurring of speech.

Impaired ventilation must be recognized early; mounting anxiety, restlessness, and fatigue are early indications for preemptive intervention. Tracheostomy is indicated for some patients with pure bulbar poliomyelitis, spinal respiratory muscle paralysis, or bulbospinal paralysis because such patients are generally unable to cough, sometimes for many months. Mechanical respirators are often needed.

Complications

Paralytic poliomyelitis may be associated with numerous complications. Acute gastric dilation may occur abruptly during the acute or convalescent stage, causing further respiratory embarrassment; immediate gastric aspiration and external application of ice bags are indicated. Melena severe enough to require transfusion may result from single or multiple superficial intestinal erosions; perforation is rare. Mild hypertension for days or weeks is common in the acute stage and probably related to lesions of the vasoregulatory centers in the medulla and especially to underventilation. In the later stages, because of immobilization, hypertension may occur along with hypercalcemia, nephrocalcinosis, and vascular lesions. Dimness of vision, headache, and a lightheaded feeling associated with hypertension should be regarded as premonitory of a frank convulsion. Cardiac irregularities are uncommon, but electrocardiographic abnormalities suggesting myocarditis occur with some frequency. Acute pulmonary edema occurs occasionally, particularly in patients with arterial hypertension. Hypercalcemia occurs because of skeletal decalcification that begins soon after immobilization and results in hypercalciuria, which in turn predisposes the patient to urinary calculi, especially when urinary stasis and infection are present. High fluid intake is the only effective prophylactic measure.

Prognosis

The outcome of inapparent, abortive poliomyelitis and aseptic meningitis syndromes is uniformly good, with death being exceedingly rare and with no long-term sequelae. The outcome of paralytic disease is determined primarily by degree and severity of CNS involvement. In severe bulbar poliomyelitis, the mortality rate may be as high as 60%, whereas in less-severe bulbar involvement and/or spinal poliomyelitis, the mortality rate varies from 5% to 10%, death generally occurring from causes other than the poliovirus infection.

Maximum paralysis usually occurs 2-3 days after the onset of the paralytic phase of the illness, with stabilization followed by gradual return of muscle function. The recovery phase lasts usually about 6 mo, beyond which persisting paralysis is permanent. In general, paralysis is more likely to develop in male children and female adults. Mortality and the degree of disability are greater after the age of puberty. Pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for paralytic disease. Tonsillectomy and intramuscular injections may enhance the risk for acquisition of bulbar and localized disease, respectively. Increased physical activity, exercise, and fatigue during the early phase of illness have been cited as factors leading to a higher risk for paralytic disease. Finally, it has been clearly demonstrated that type 1 poliovirus has the greatest propensity for natural poliomyelitis and type 3 poliovirus has a predilection for producing VAPP.

Postpolio Syndrome

After an interval of 30-40 yr, as many as 30–40% of persons who survived paralytic poliomyelitis in childhood may experience muscle pain and exacerbation of existing weakness or development of new weakness or paralysis. This entity, referred to as postpolio syndrome, has been reported only in persons who were infected in the era of wild-type poliovirus circulation. Risk factors for postpolio syndrome include increasing length of time since acute poliovirus infection, presence of permanent residual impairment after recovery from acute illness, and female sex.

Prevention

Vaccination is the only effective method of preventing poliomyelitis. Hygienic measures help to limit the spread of the infection among young children, but immunization is necessary to control transmission among all age groups. Both the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is currently produced using better methods than those for the original vaccine and is sometimes referred to as enhanced IPV, and the live-attenuated OPV have established efficacy in preventing poliovirus infection and paralytic poliomyelitis. Both vaccines induce production of antibodies against the 3 strains of poliovirus. IPV elicits higher serum IgG antibody titers, but the OPV also induces significantly greater mucosal IgA immunity in the oropharynx and gastrointestinal tract, which limits replication of the wild poliovirus at these sites. Transmission of wild poliovirus by fecal spread is limited in OPV recipients. The immunogenicity of IPV is not affected by the presence of maternal antibodies, and IPV has no adverse effects. Live vaccine may undergo reversion to neurovirulence as it multiplies in the human intestinal tract and may cause VAPP in vaccinees or in their contacts. The overall risk for recipients varies from 1 case per 750,000 immunized infants in the United States to 1 in 143,000 immunized infants in India. The risk for paralysis in the B-cell–immunodeficient recipient may be as much as 6,800 times that in normal subjects. HIV infection has not been found to result in long-term excretion of virus. As of January 2000, the IPV-only schedule is recommended for routine polio vaccination in the United States. All children should receive 4 doses of IPV, at 2 mo, 4 mo, 6-18 mo, and 4-6 yr of age.

In 1988 the World Health Assembly resolved to eradicate poliomyelitis globally by 2000, and remarkable progress had been made toward reaching this target. To achieve this goal, the WHO used 4 basic strategies: routine immunization, National Immunization Days, acute flaccid paralysis surveillance, and mop-up immunization. This strategy has resulted in a >99% decline in poliomyelitis cases; in early 2002, there were only 10 countries in the world endemic for poliomyelitis. In 2012 there were the fewest cases of poliomyelitis ever, and the virus was endemic in only 3 countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria). India has not had a child paralyzed with wild poliovirus type 2 since February 2011. The last case of wild poliovirus type 3 infection occurred in Nigeria in November 2012, and the last case of wild poliovirus type 2 infection occurred in India in October 1999. This progress prompted the WHO assembly, in May 2013, to recommend the development of a Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan 2013-2018. This plan included the withdrawal of trivalent OPV (tOPV) with bivalent OPV (bOPV) in all countries by 2016 and the introduction of initially 1 dose of IPV followed by the replacement of bOPV with IPV in all countries of the world by 2019. As long as the OPV is being used, there is the potential that vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) will acquire the neurovirulent phenotype and transmission characteristics of the wild-type polioviruses. VDPV emerges from the OPV because of continuous replication in immunodeficient persons (iVDPV) or by circulation in populations with low vaccine coverage (cVDPVs). The risk was highest with the type 2 strain. Between 2000 and 2012, 90% of the 750 paralytic cases of cVDPV and 40% of VAPP were caused by type 2 strains. Between 17 April and 1 May 2016, 155 countries and territories in the world switched from the use of tOPV to bOPV. tOPV is no longer used globally in any routine or supplemental immunization activities.

Several countries are global priorities because they face challenges in eradication of the disease. Polioviruses remain endemic in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria. For these 3 countries, there are several reasons for the failure to eradicate polio. The rejection of poliovirus vaccine initiatives and campaign quality in security-compromised areas in parts of these countries are still the main difficulties faced in 2019. Following an emergency committee meeting in November 2018 that reviewed data on WPV1 and cVDPV, new recommendations for international travelers to certain countries were made by the WHO and endorsed by the CDC. There has been an increase in WPV1 (21 cases each in Afghanistan and Nigeria and 12 in Pakistan in 2018). In addition, outbreaks of cVDPV2 in Syria, Somalia, Kenya, DR Congo, Niger, and Mozambique, cVDPV1 in Papua New Guinea, and cVDPV3 in Somalia, with spread of cVDPV2 between Somalia and Kenya and between Nigeria and Niger, highlight that routine immunization coverage remains very poor in many areas of these countries. Continuing spread due to poor herd immunity and now international spread pose a significant threat to the eradication effort. The committee recommended that for countries with WPV1, cVDPV1, or cVDPV3 with potential risk of international spread, all residents and long-term visitors (i.e., >4 weeks) of all ages receive a dose of bOPV or IPV between 4 wk and 12 mo before travel to these countries (currently Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, and Somalia). Such travelers should be provided with an International Certificate of Vaccination of Prophylaxis to record their polio vaccination and service proof of vaccination. These countries have been advised to restrict at the point of departure the international travel of any resident lacking documentation of full vaccination, whether by air, sea, or land. For countries infected with cVDPV2 with potential risk of international spread (DR Congo, Kenya, Nigeria, Niger, and Somalia as of January 2019), visitors should be encouraged to follow these recommendations (not mandated).

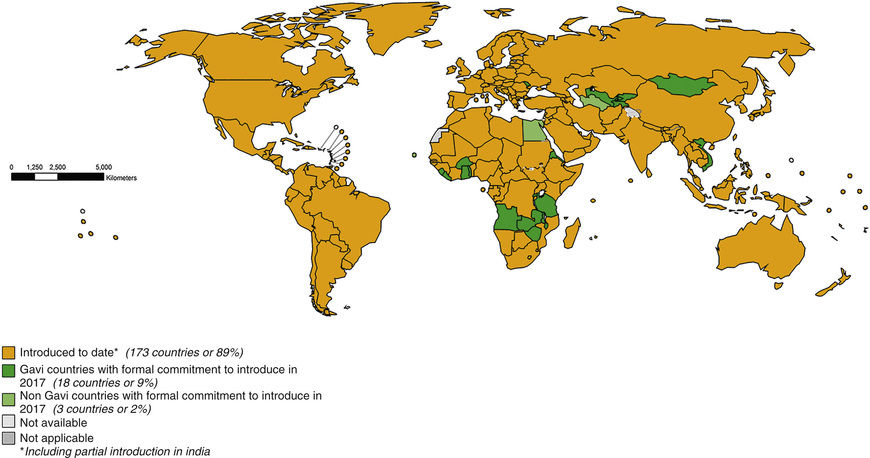

In October 2016, cVDPV2 was isolated from the sewage in different parts of India, most probably due to the use of tOPV, which was still being used in private dispensaries and was not destroyed as was mandated. This illustrates the dangers of purely using bOPV. The WHO has mandated that infants in all countries still using bOPV should receive a dose of IPV, to offer protection against polio virus type 2. All countries have complied with this requirement; see Fig. 276.1

for the status as of November 2016. In this regard, recent studies from India have shown that following a course of OPV, IPV boosts serologic and mucosal immunity that lasts for at least 11 mo. It is estimated that between 12 and 24 mo after withdrawal of Sabin poliovirus type 2 vaccine, the world would have eradicated type 2 poliovirus circulation in humans. The switch from bOPV to IPV worldwide is slated to occur soon thereafter. These efforts may be stymied because of the global inability to produce IPV in a large enough volume to cover all the 128 million babies born annually in the world. This problem was a crisis during the global synchronized introduction of bOPV, when several countries (e.g., India) had to use 2 fractional doses of IPV ( dose) administered intradermally. To enhance scale up of IPV production in countries such as India, Brazil, and China, IPV using Sabin strains of poliovirus have been developed in Japan and China. These mitigate the stringent requirements for wild-type poliovirus culture that are normally required for IPV production. Other strategies include developing adjuvants for IPV that could potentially lower the antigen quantities needed for each dose.

dose) administered intradermally. To enhance scale up of IPV production in countries such as India, Brazil, and China, IPV using Sabin strains of poliovirus have been developed in Japan and China. These mitigate the stringent requirements for wild-type poliovirus culture that are normally required for IPV production. Other strategies include developing adjuvants for IPV that could potentially lower the antigen quantities needed for each dose.

In countries where bOPV is included in routine immunization, it is best if it follows at least 1 dose of IPV or 2 doses of fractional intradermal IPV. This follows the experience in the United States and Hungary that reported no VAPP following a sequential use of IPV followed by OPV. Global synchronous cessation of OPV will need to be coordinated by the WHO, but the recent experiences in the horn of Africa and Israel/West Bank suggest that stopping transmission of wild poliovirus type 1 in the 3 endemic countries is of the utmost urgency, if we are to stop using OPV.