Cleft Lip and Palate

Vineet Dhar

Clefts of the lip and palate are distinct entities which are closely related embryologically, functionally, and genetically. It is thought that cleft of the lip appears because of hypoplasia of the mesenchymal layer, resulting in a failure of the medial nasal and maxillary processes to join. Cleft of the palate results from failure of palatal shelves to approximate or fuse.

Incidence and Epidemiology

The incidence of cleft lip with or without cleft palate is approximately 1 in 750 white births; the incidence of cleft palate alone is approximately 1 in 2,500 white births. Clefts of the lip are more common in males. Possible causes include maternal drug exposure, a syndrome-malformation complex, or genetic factors. Although clefts of lips and palates appear to occur sporadically, the presence of susceptible genes appears important. There are approximately 400 syndromes associated with cleft lip and palates. There are families in which a cleft lip or palate, or both, is inherited in a dominant fashion (van der Woude syndrome ), and careful examination of parents is important to distinguish this type from others, because the recurrence risk is 50%. Ethnic factors also affect the incidence of cleft lip and palate; the incidence is highest among Asians (~1 in 500) and Native Americans (~1 in 300) and lowest among blacks (~1 in 2,500). Cleft lip may be associated with other cranial facial anomalies, whereas cleft palate may be associated with central nervous system anomalies.

Clinical Manifestations

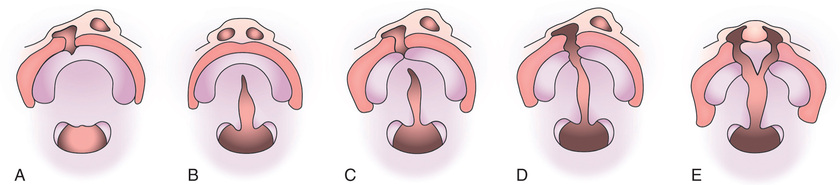

Cleft lip can vary from a small notch in the vermilion border to a complete separation involving skin, muscle, mucosa, tooth, and bone. Clefts of the lip may be unilateral (more often on the left side) or bilateral and can involve the alveolar ridge (Fig. 336.1 ).

Isolated cleft palate occurs in the midline and might involve only the uvula or can extend into or through the soft and hard palates to the incisive foramen. When associated with cleft lip, the defect can involve the midline of the soft palate and extend into the hard palate on one or both sides, exposing one or both of the nasal cavities as a unilateral or bilateral cleft palate. The palate can also have a submucosal cleft indicated by a bifid uvula, partial separation of muscle with intact mucosa, or a palpable notch at the posterior of the palate (see Fig. 336.1 ).

Treatment

A complete program of habilitation for the child with a cleft lip or palate can require years of special treatment by a team consisting of a pediatrician, plastic surgeon, otolaryngologist, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, pediatric dentist, prosthodontist, orthodontist, speech therapist, geneticist, medical social worker, psychologist, and public health nurse.

The immediate problem in an infant born with a cleft lip or palate is feeding. Although some advocate the construction of a plastic obturator to assist in feedings, most believe that, with the use of soft artificial nipples with large openings, a squeezable bottle, and proper instruction, feeding of infants with clefts can be achieved.

Surgical closure of a cleft lip is usually performed by 3 mo of age, when the infant has shown satisfactory weight gain and is free of any oral, respiratory, or systemic infection. Modification of the Millard rotation–advancement technique is the most commonly used technique; a staggered suture line minimizes notching of the lip from retraction of scar tissue. The initial repair may be revised at 4 or 5 yr of age. Corrective surgery on the nose may be delayed until adolescence. Nasal surgery can also be performed at the time of the lip repair. Cosmetic results depend on the extent of the original deformity, healing potential of the individual patient, absence of infection, and the skill of the surgeon.

Because clefts of the palate vary considerably in size, shape, and degree of deformity, the timing of surgical correction should be individualized. Criteria such as width of the cleft, adequacy of the existing palatal segments, morphology of the surrounding areas (width of the oropharynx), and neuromuscular function of the soft palate and pharyngeal walls affect the decision. The goals of surgery are the union of the cleft segments, intelligible and pleasant speech, reduction of nasal regurgitation, and avoidance of injury to the growing maxilla.

In an otherwise healthy child, closure of the palate is usually done before 1 yr of age to enhance normal speech development. When surgical correction is delayed beyond the 3rd yr, a contoured speech bulb can be attached to the posterior of a maxillary denture so that contraction of the pharyngeal and velopharyngeal muscles can bring tissues into contact with the bulb to accomplish occlusion of the nasopharynx and help the child to develop intelligible speech.

A cleft palate usually crosses the alveolar ridge and interferes with the formation of teeth in the maxillary anterior region. Teeth in the cleft area may be displaced, malformed, or missing. Missing teeth or teeth that are nonfunctional are replaced by prosthetic devices.

Postoperative Management

During the immediate postoperative period, special nursing care is essential. Gentle aspiration of the nasopharynx minimizes the chances of the common complications of atelectasis or pneumonia. The primary considerations in postoperative care are maintenance of a clean suture line and avoidance of tension on the sutures. The infant is fed with a specially designed bottle and the arms are restrained with elbow cuffs. A fluid or semifluid diet is maintained for 3 wk. The patient's hands, toys, and other foreign bodies must be kept away from the surgical site.

Sequelae

Recurrent otitis media and subsequent hearing loss are frequent with cleft palate. Displacement of the maxillary arches and malposition of the teeth usually require orthodontic correction. Misarticulations and velopharyngeal dysfunction are often associated with cleft lip and palate and may be present or persist because of physiologic dysfunction, anatomic insufficiency, malocclusion, or inadequate surgical closure of the palate. Such speech is characterized by the emission of air from the nose and by a hypernasal quality with certain sounds, or by compensatory misarticulations (glottal stops). Before and sometimes after palatal surgery, the speech defect is caused by inadequacies in function of the palatal and pharyngeal muscles. The muscles of the soft palate and the lateral and posterior walls of the nasopharynx constitute a valve that separates the nasopharynx from the oropharynx during swallowing and in the production of certain sounds. If the valve does not function adequately, it is difficult to build up enough pressure in the mouth to make such explosive sounds as p, b, d, t, h, y, or the sibilants s, sh, and ch, and such words as “cats,” “boats,” and “sisters” are not intelligible. After operation or the insertion of a speech appliance, speech therapy is necessary.

Velopharyngeal Dysfunction

The speech disturbance characteristic of the child with a cleft palate can also be produced by other osseous or neuromuscular abnormalities where there is an inability to form an effective seal between oropharynx and nasopharynx during swallowing or phonation. In a child who has the potential for abnormal speech, adenoidectomy can precipitate overt hypernasality. If the neuromuscular function is adequate, compensation in palatopharyngeal movement might take place and the speech defect might improve, although speech therapy is necessary. In other cases, slow involution of the adenoids can allow gradual compensation in palatal and pharyngeal muscular function. This might explain why a speech defect does not become apparent in some children who have a submucous cleft palate or similar anomaly predisposing to palatopharyngeal incompetence.

Clinical Manifestations

Although clinical signs vary, the symptoms of velopharyngeal dysfunction are similar to those of a cleft palate. There may be hypernasal speech (especially noted in the articulation of pressure consonants such as p, b, d, t, h, v, f, and s); conspicuous constricting movement of the nares during speech; inability to whistle, gargle, blow out a candle, or inflate a balloon; loss of liquid through the nose when drinking with the head down; otitis media; and hearing loss. Oral inspection might reveal a cleft palate or a relatively short palate with a large oropharynx; absent, grossly asymmetric, or minimal muscular activity of the soft palate and pharynx during phonation or gagging; or a submucous cleft.

Velopharyngeal dysfunction may also be demonstrated radiographically. The head should be carefully positioned to obtain a true lateral view; one film is obtained with the patient at rest and another during continuous phonation of the vowel u as in “boom.” The soft palate contacts the posterior pharyngeal wall in normal function, whereas in velopharyngeal dysfunction such contact is absent.

In selected cases of velopharyngeal dysfunction, the palate may be retropositioned or pharyngoplasty may be performed using a flap of tissue from the posterior pharyngeal wall. Dental speech appliances have also been used successfully. The type of surgery used is best tailored to the findings on nasoendoscopy.