Congenital Anomalies

Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Seema Khan, Sravan Kumar Reddy Matta

Esophageal atresia (EA) is the most common congenital anomaly of the esophagus, with a prevalence of 1.7 per 10,000 live births. Of these, >90% have an associated tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). In the most common form of EA, the upper esophagus ends in a blind pouch and the TEF is connected to the distal esophagus (type C). Fig. 345.1 shows the types of EA and TEF and their relative frequencies. The exact cause is still unknown; associated features include advanced maternal age, European ethnicity, obesity, low socioeconomic status, and tobacco smoking. This defect has survival rates of >90%, owing largely to improved neonatal intensive care, earlier recognition, and appropriate intervention. Infants weighing <1,500 g at birth and those with severe associated cardiac anomalies have the highest risk for mortality. Fifty percent of infants are nonsyndromic without other anomalies, and the rest have associated anomalies, most often associated with the vertebral, anorectal, (cardiac), tracheal, esophageal, renal, radial, (limb) (VACTERL) syndrome. Cardiac and vertebral anomalies are seen in 32% and 24%, respectively. VACTERL is generally associated with normal intelligence. Despite low concordance among twins and the low incidence of familial cases, genetic factors have a role in the pathogenesis of TEF in some patients as suggested by discrete mutations in syndromic cases: Feingold syndrome (N-MYC), CHARGE syndrome (c oloboma of the eye; c entral nervous system anomalies; h eart defects; a tresia of the choanae; r etardation of growth and/or development; g enital and/or urinary defects [hypogonadism]; e ar anomalies and/or deafness) (CHD7), and anophthalmia-esophageal-genital syndrome (SOX2).

Presentation

The neonate with EA typically has frothing and bubbling at the mouth and nose after birth as well as episodes of coughing, cyanosis, and respiratory distress. Feeding exacerbates these symptoms, causes regurgitation, and can precipitate aspiration. Aspiration of gastric contents via a distal fistula causes more damaging pneumonitis than aspiration of pharyngeal secretions from the blind upper pouch. The infant with an isolated TEF in the absence of EA (“H-type” fistula) might come to medical attention later in life with chronic respiratory problems, including refractory bronchospasm and recurrent pneumonias.

Diagnosis

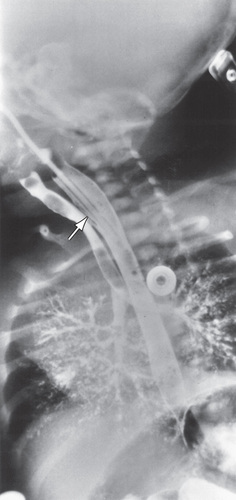

In the setting of early-onset respiratory distress, the inability to pass a nasogastric or orogastric tube in the newborn suggests EA. Imaging findings of absence of the fetal stomach bubble and maternal polyhydramnios might alert the physician to EA before birth. Plain radiography in the evaluation of respiratory distress might reveal a coiled feeding tube in the esophageal pouch and/or an air-distended stomach, indicating the presence of a coexisting TEF (Fig. 345.2 ). Conversely, pure EA can manifest as an airless scaphoid abdomen. In isolated TEF (H type), an esophagogram with contrast medium injected under pressure can demonstrate the defect (Fig. 345.3 ). Alternatively, the orifice may be detected at bronchoscopy or when methylene blue dye injected into the endotracheal tube during endoscopy is observed in the esophagus during forced inspiration. The differential diagnosis of congenital esophageal lesions is noted in Table 345.1 .

Table 345.1

Clinical Aspects of Esophageal Developmental Anomalies

| ANOMALY | AGE AT PRESENTATION | PREDOMINANT SYMPTOMS | DIAGNOSIS | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated atresia | Newborns |

Regurgitation of feedings Aspiration |

Esophagogram* Plain film: gasless abdomen |

Surgery |

| Atresia + distal TEF | Newborns |

Regurgitation of feedings Aspiration |

Esophagogram* Plain film: gas-filled abdomen |

Surgery |

| H-type TEF | Infants to adults |

Recurrent pneumonia Bronchiectasis |

Esophagogram* Bronchoscopy † |

Surgery |

| Esophageal stenosis | Infants to adults |

Dysphagia Food impaction |

Esophagogram* Endoscopy † |

Dilation ‡ Surgery § |

| Duplication cyst | Infants to adults |

Dyspnea, stridor, cough (infants) Dysphagia, chest pain (adults) |

EUS* MRI/CT † |

Surgery |

| Vascular anomaly | Infants to adults |

Dyspnea, stridor, cough (infants) Dysphagia (adults) |

Esophagogram* Angiography † MRI/CT/EUS |

Dietary modification ‡ Surgery § |

| Esophageal ring | Children to adults | Dysphagia |

Esophagogram* Endoscopy † |

Dilation ‡ Endoscopic incision § |

| Esophageal web | Children to adults | Dysphagia |

Esophagogram* Endoscopy † |

Bougienage |

* Diagnostic test of choice.

† Confirmatory test.

‡ Primary therapeutic approach.

§ Secondary therapeutic approach.

TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula.

From Madanick R, Orlando RC: Anatomy, histology, embryology, and developmental anomalies of the esophagus. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors: Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease , ed 10, New York, 2016, Elsevier, Table 42.2.

Management

Initially, maintaining a patent airway, pre-operative proximal pouch decompression to prevent aspiration of secretions, and use of antibiotics to prevent consequent pneumonia are paramount. Prone positioning minimizes movement of gastric secretions into a distal fistula, and esophageal suctioning minimizes aspiration from a blind pouch. Endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation is to be avoided if possible because it can worsen distention of the stomach. Surgical ligation of the TEF and primary end-to-end anastomosis of the esophagus via right-sided thoracotomy constitute the current standard surgical approach. In the premature or otherwise complicated infant, a primary closure may be delayed by temporizing with fistula ligation and gastrostomy tube placement. If the gap between the atretic ends of the esophagus is >3 to 4 cm (>3 vertebral bodies), primary repair cannot be done; options include using gastric, jejunal, or colonic segments interposed as a neoesophagus. Careful search must be undertaken for the common associated cardiac and other anomalies. Thoracoscopic surgical repair is feasible and associated with favorable long-term outcomes.

Outcome

The majority of children with EA and TEF grow up to lead normal lives, but complications are often challenging, particularly during the first 5 yr of life. Complications of surgery include anastomotic leak, refistulization, and anastomotic stricture. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, resulting from intrinsic abnormalities of esophageal function, often combined with delayed gastric emptying, contributes to management challenges in many cases. Gastroesophageal reflux disease contributes significantly to the respiratory disease (reactive airway disease) that often complicates EA and TEF and also worsens the frequent anastomotic strictures after repair of EA.

Many patients have an associated tracheomalacia that improves as the child grows. Hence, it is important to target on prevention of long-term complications using appropriate surveillance techniques (endoscopy, pH-Impedance).

Bibliography

Achildi O, Grewal H. Congenital anomalies of the esophagus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am . 2007;40:219–244.

Brookes JT, Smith MC, Smith RJH, et al. H-type congenital tracheoesophageal fistula: university of iowa experience 1985-2005. Ann Otolo Rhinol Laryngol . 2007;116(5):363–368.

Burge DM, Shah K, Spark P, et al. Contemporary management and outcomes for infants born with oesophageal atresia. Br J Surg . 2013;100:515–521.

Castilloux J, Noble AJ, Faure C. Risk factors for short- and long-term morbidity in children with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr . 2010;156:755–760.

Keckler SJ, St Peter SD, Valusek PA, et al. VACTERL anomalies in patients with esophageal atresia: an updated delineation of the spectrum and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int . 2007;23:309–313.

Singh A, Middlesworth W. Khlevner J. Curr Gastroenterol Rep . 2017;19:4.

Smith N. Oesophageal atresia and trachea-oesophageal fistula. Early Hum Dev . 2014;90:947–950.

Laryngotracheoesophageal Clefts

Seema Khan, Sravan Kumar Reddy Matta

Laryngotracheoesophageal clefts are uncommon anomalies that result when the septum between the esophagus and trachea fails to develop fully, leading to a common channel defect between the pharyngoesophagus and laryngotracheal lumen, thus making the laryngeal closure incompetent during swallowing or reflux. Other developmental anomalies, such as EA and TEF, are seen in 20% of patients with clefts. The severity of presenting symptoms depends on the type of cleft; they are commonly classified as four types (I-IV) according to the inferior extent of the cleft. Early in life, the infant presents with stridor, choking, cyanosis, aspiration of feedings, and recurrent chest infections. The diagnosis is difficult and usually requires direct endoscopic visualization of the larynx and esophagus. When contrast radiography is used, material is often seen in the esophagus and trachea. Treatment is surgical repair, which can be complex if the defects are long.

Congenital Esophageal Stenosis

Seema Khan, Sravan Kumar Reddy Matta

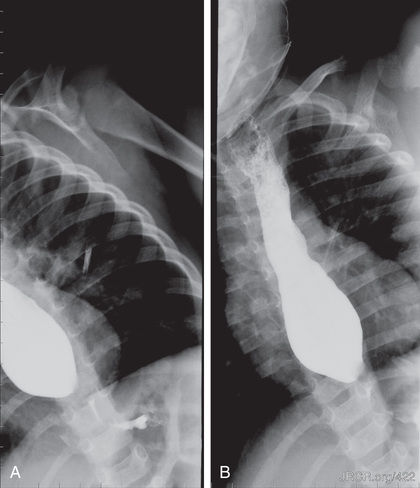

Congenital esophageal stenosis (CES) is a rare anomaly of the esophagus with clinical significance. Though the original incidence is not known, it is estimated to affect 1 : 25,000 to 50,000 live births. The defect results from incomplete separation of respiratory tract from the primitive foregut at 25th day of fetal life. CES is differentiated by histology into 3 types: esophageal membrane/web, total bronchial remnants (TBR), and fibromuscular remnants (FMR). Symptoms vary depending on the location and severity of the defect. Higher lesions present with respiratory symptoms and lower lesions present with dysphagia and vomiting. Esophagogram (Fig. 345.4 ), MRI, CT, and endoscopic ultrasound are used for diagnosis. Endoscopy (Fig. 345.5 ) is done to evaluate mucosal abnormalities like strictures, foreign bodies, and esophagitis. Treatment option (surgical correction, bougie dilation) is chosen based on the location, severity, and type of stenosis.

Bibliography

Amae S, Nio M, Kamiyama T, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of congenital esophageal stenosis: a report on 14 cases. J Pediatr Surg . 2003;38:565–570.

Michaud L, Coutenier F, Podevin G. Characteristics and management of congenital esophageal stenosis: findings from a multicenter study. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2013;8:186.

Serrao E, Santos A, Gaivao A. Congenital esophageal stenosis: a rare case of dysphagia. J Radiol Case Rep . 2010;4(6):8–14.