Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Seema Khan, Sravan Kumar Reddy Matta

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common esophageal disorder in children of all ages. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) signifies the retrograde movement of gastric contents across the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) into the esophagus, which occurs physiologically every day in all infants, older children, and adults. Physiologic GER is exemplified by the effortless regurgitation of normal infants. The phenomenon becomes pathologic GERD in infants and children who manifest or report bothersome symptoms because of frequent or persistent GER, producing esophagitis-related symptoms, or extra-esophageal presentations, such as respiratory symptoms or nutritional effects.

Pathophysiology

Factors determining the esophageal manifestations of reflux include the duration of esophageal exposure (a product of the frequency and duration of reflux episodes), the causticity of the refluxate, and the susceptibility of the esophagus to damage. The LES, defined as a high-pressure zone by manometry, is supported by the crura of the diaphragm at the gastroesophageal junction, together with valve-like functions of the esophagogastric junction anatomy, form the antireflux barrier. In the context of even the normal intraabdominal pressure augmentations that occur during daily life, the frequency of reflux episodes is increased by insufficient LES tone, by abnormal frequency of LES relaxations, and by hiatal herniation that prevents the LES pressure from being proportionately augmented by the crura during abdominal straining. Normal intraabdominal pressure augmentations may be further exacerbated by straining or respiratory efforts. The duration of reflux episodes is increased by lack of swallowing (e.g., during sleep) and by defective esophageal peristalsis. Vicious cycles ensue because chronic esophagitis produces esophageal peristaltic dysfunction (low-amplitude waves, propagation disturbances), decreased LES tone, and inflammatory esophageal shortening that induces hiatal herniation, all worsening reflux.

Transient LES relaxation (TLESR) is the primary mechanism allowing reflux to occur, and is defined as simultaneous relaxation of both LES and the surrounding crura. TLESRs occur independent of swallowing, reduce LES pressure to 0-2 mm Hg (above gastric), and last 10-60 sec; they appear by 26 wk of gestation. A vagovagal reflex, composed of afferent mechanoreceptors in the proximal stomach, a brainstem pattern generator, and efferents in the LES, regulates TLESRs. Gastric distention (postprandially, or from abnormal gastric emptying or air swallowing) is the main stimulus for TLESRs. Whether GERD is caused by a higher frequency of TLESRs or by a greater incidence of reflux during TLESRs is debated; each is likely in different persons. Straining during a TLESR makes reflux more likely, as do positions that place the gastroesophageal junction below the air–fluid interface in the stomach. Other factors influencing gastric pressure–volume dynamics, such as increased movement, straining, obesity, large-volume or hyperosmolar meals, gastroparesis, a large sliding hiatal hernia, and increased respiratory effort (coughing, wheezing) can have the same effect.

Epidemiology and Natural History

Infant reflux becomes evident in the first few mo of life, peaks at 4 mo, and resolves in up to 88% by 12 mo and in nearly all by 24 mo. Happy spitters are infants who have recurrent regurgitation without exhibiting discomfort or refusal to eat and failure to gain weight. Symptoms of GERD in older children tend to be chronic, waxing and waning, but completely resolving in no more than half, which resembles adult patterns (Table 349.1 ). The histologic findings of esophagitis persist in infants who have naturally resolving symptoms of reflux. GERD likely has genetic predispositions: family clustering of GERD symptoms, endoscopic esophagitis, hiatal hernia, Barrett esophagus, and adenocarcinoma have been identified. As a continuously variable and common disorder, complex inheritance involving multiple genes and environmental factors is likely. Genetic linkage is indicated by the strong evidence of GERD in studies with monozygotic twins. A pediatric autosomal dominant form with otolaryngologic and respiratory manifestations has been located to chromosome 13q14, and the locus is termed GERD1.

Table 349.1

| MANIFESTATIONS | INFANTS | CHILDREN | ADOLESCENTS AND ADULTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired quality of life | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Regurgitation | ++++ | + | + |

| Excessive crying/irritability | +++ | + | – |

| Vomiting | ++ | ++ | + |

| Food refusal/feeding disturbances/anorexia | ++ | + | + |

| Persisting hiccups | ++ | + | + |

| Failure to thrive | ++ | + | – |

| Abnormal posturing/Sandifer syndrome | ++ | + | – |

| Esophagitis | + | ++ | +++ |

| Persistent cough/aspiration pneumonia | + | ++ | + |

| Wheezing/laryngitis/ear problems | + | ++ | + |

| Laryngomalacia/stridor/croup | + | ++ | – |

| Sleeping disturbances | + | + | + |

| Anemia/melena/hematemesis | + | + | + |

| Apnea/BRUE/desaturation | + | – | – |

| Bradycardia | + | ? | ? |

| Heartburn/pyrosis | ? | ++ | +++ |

| Epigastric pain | ? | + | ++ |

| Chest pain | ? | + | ++ |

| Dysphagia | ? | + | ++ |

| Dental erosions/water brush | ? | + | + |

| Hoarseness/globus pharyngeus | ? | + | + |

| Chronic asthma/sinusitis | – | ++ | + |

| Laryngostenosis/vocal nodule problems | – | + | + |

| Stenosis | – | (+) | + |

| Barrett/esophageal adenocarcinoma | – | (+) | + |

+++ , Very common; ++ common; + possible; (+) rare; − absent; ? unknown; BRUE , brief resolved unexplained event; previously called as ALTE , apparent life-threatening event.

From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2011, WB Saunders, Table 22.3, p. 235.

Clinical Manifestations

Most of the common clinical manifestations of esophageal disease can signify the presence of GERD and are generally thought to be mediated by the pathogenesis involving acid GER (Table 349.2 ). Although less noxious for the esophageal mucosa, nonacid reflux events are recognized to play an important role in extraesophageal disease manifestations. Infantile reflux manifests more often with regurgitation (especially postprandially), signs of esophagitis (irritability, arching, choking, gagging, feeding aversion), and resulting failure to thrive; symptoms resolve spontaneously in the majority of infants by 12-24 mo. Older children can have regurgitation during the preschool years; this complaint diminishes somewhat as children age, and complaints of abdominal and chest pain supervene in later childhood and adolescence. Occasional children present with food refusal or neck contortions (arching, turning of head) designated Sandifer syndrome. The respiratory presentations are also age dependent: GERD in infants may manifest as obstructive apnea or as stridor or lower airway disease in which reflux complicates primary airway disease such as laryngomalacia or bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Otitis media, sinusitis, lymphoid hyperplasia, hoarseness, vocal cord nodules, and laryngeal edema have all been associated with GERD. Airway manifestations in older children are more commonly related to asthma or to otolaryngologic disease such as laryngitis or sinusitis. Despite the high prevalence of GERD symptoms in asthmatic children, data showing direction of causality are conflicting.

Table 349.2

Symptoms and Signs That May Be Associated With Gastroesophageal Reflux

| SYMPTOMS |

| SIGNS |

From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2011, WB Saunders, Table 22.1, p. 235.

Neurologically challenged children are one group that is recognized to be at an increased risk for GERD. It is not well established if the greater risk is conferred due to inadequate defensive mechanisms and/or inability to express symptoms. A low clinical threshold is important in the early identification and prompt treatment of GERD symptoms in these individuals.

Diagnosis

For most of the typical GERD presentations, particularly in older children, a thorough history and physical examination suffice initially to reach the diagnosis. This initial evaluation aims to identify the pertinent positives in support of GERD and its complications and the negatives that make other diagnoses unlikely. The history may be facilitated and standardized by questionnaires (e.g., the Infant Gastroesophageal Reflux Questionnaire, the I-GERQ, and its derivative, the I-GERQ-R), which also permit quantitative scores to be evaluated for their diagnostic discrimination and for evaluative assessment of improvement or worsening of symptoms. The clinician should be alerted to the possibility of other important diagnoses in the presence of any alarm or warning signs : bilious emesis, frequent projectile emesis, gastrointestinal bleeding, lethargy, organomegaly, abdominal distention, micro- or macrocephaly, hepatosplenomegaly, failure to thrive, diarrhea, fever, bulging fontanelle, and seizures. The important differential diagnoses to consider in the evaluation of an infant or a child with chronic vomiting are milk and other food allergies, eosinophilic esophagitis, pyloric stenosis, intestinal obstruction (especially malrotation with intermittent volvulus), nonesophageal inflammatory diseases, infections, inborn errors of metabolism, hydronephrosis, increased intracranial pressure, rumination, and bulimia. Focused diagnostic testing, depending on the presentation and the differential diagnosis, can then supplement the initial examination.

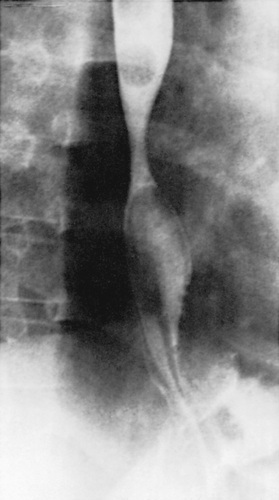

Most of the esophageal tests are of some use in particular patients with suspected GERD. Contrast (usually barium) radiographic study of the esophagus and upper gastrointestinal tract is performed in children with vomiting and dysphagia to evaluate for achalasia, esophageal strictures and stenosis, hiatal hernia, and gastric outlet or intestinal obstruction (Fig. 349.1 ). It has poor sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of GERD as a result of its limited duration and the inability to differentiate physiologic GER from GERD. Furthermore, contrast radiography neither accurately assesses mucosal inflammation nor correlates with severity of GERD.

Extended esophageal pH monitoring of the distal esophagus, no longer considered the sine qua non of a GERD diagnosis, provides a quantitative and sensitive documentation of acidic reflux episodes, the most important type of reflux episodes for pathologic reflux. The distal esophageal pH probe is placed at a level corresponding to 87% of the nares-LES distance, based on regression equations using the patient's height, on fluoroscopic visualization, or on manometric identification of the LES. Normal values of distal esophageal acid exposure (pH <4) are generally established as <5 to 8% of the total monitored time, but these quantitative normals are insufficient to establish or disprove a diagnosis of pathologic GERD. The most important indications for esophageal pH monitoring are for assessing efficacy of acid suppression during treatment, evaluating apneic episodes in conjunction with a pneumogram and perhaps impedance, and evaluating atypical GERD presentations such as chronic cough, stridor, and asthma. Dual pH probes, adding a proximal esophageal probe to the standard distal one, are used in the diagnosis of extraesophageal GERD, identifying upper esophageal acid exposure times of 1% of the total time as threshold values for abnormality.

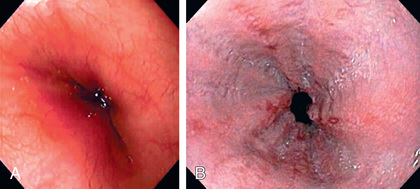

Endoscopy allows diagnosis of erosive esophagitis (Fig. 349.2 ) and complications such as strictures or Barrett esophagus; esophageal biopsies can diagnose histologic reflux esophagitis in the absence of erosions while simultaneously eliminating allergic and infectious causes. Endoscopy is also used therapeutically to dilate reflux-induced strictures. Radionucleotide scintigraphy using technetium can demonstrate aspiration and delayed gastric emptying when these are suspected.

The multichannel intraluminal impedance is a cumbersome test, but with potential applications both for diagnosing GERD and for understanding esophageal function in terms of bolus flow, volume clearance, and (in conjunction with manometry) motor patterns associated with GERD. Owing to the multiple sensors and a distal pH sensor, it is possible to document acidic reflux (pH <4), weakly acidic reflux (pH 4-7), and weakly alkaline reflux (pH >7) with multichannel intraluminal impedance. It is an important tool in those with respiratory symptoms, particularly for the determination of nonacid reflux, but must be cautiously applied in routine clinical evaluation because of limited evidence-based parameters for GERD diagnosis and symptom association.

Esophageal manometry is not useful in demonstrating gastroesophageal reflux but might be of use to evaluate transient LES relaxations and pressures.

Laryngotracheobronchoscopy evaluates for visible airway signs that are associated with extraesophageal GERD, such as posterior laryngeal inflammation and vocal cord nodules; it can permit diagnosis of silent aspiration (during swallowing or during reflux) by bronchoalveolar lavage with subsequent quantification of lipid-laden macrophages in airway secretions. Detection of pepsin in tracheal fluid is a marker of reflux-associated aspiration of gastric contents. Esophageal manometry permits evaluation for dysmotility, particularly in preparation for antireflux surgery.

Empirical antireflux therapy, using a time-limited trial of high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI), is a cost-effective strategy for diagnosis in adults; although not formally evaluated in older children, it has also been applied to this age group. Failure to respond to such empirical treatment, or a requirement for the treatment for prolonged periods, mandates formal diagnostic evaluation.

Management

Conservative therapy and lifestyle modifications that form the foundation of GERD therapy can be effectively implemented through education and reassurance for parents. Dietary measures for infants include normalization of any abnormal feeding techniques, volumes, and frequencies. Thickening of feeds or use of commercially prethickened formulas increases the percentage of infants with no regurgitation, decreases the frequency of daily regurgitation and emesis, and increases the infant's weight gain. However, caution should be exercised when managing preterm infants because of the possible association between xanthan gum-based thickened feeds and necrotizing enterocolitis. The evidence does not clearly favor 1 type of thickener over another; the addition of a Tbsp of rice or oat cereal per oz of formula results in a greater caloric density (30 kcal/oz) and reduced crying time, although it might not modify the number of nonregurgitant reflux episodes. Caution must be exercised while using rice cereal, as studies show increased risk of arsenic exposure in children with rice and rice product consumption. A short trial (2 wk) of a hypoallergenic diet in infants may be used to exclude milk or soy protein allergy before pharmacotherapy. A combination of modified feeding volumes, hydrolyzed infant formulas, proper positioning, and avoidance of smoke exposure satisfactorily improve GERD symptoms in 24–59% of infants with GERD. Older children should be counseled to avoid acidic or reflux-inducing foods (tomatoes, chocolate, mint) and beverages (juices, carbonated and caffeinated drinks, alcohol). Weight reduction for obese patients and elimination of smoke exposure are other crucial measures at all ages.

Positioning measures are particularly important for infants, who cannot control their positions independently. Seated position worsens infant reflux and should be avoided in infants with GERD. Esophageal pH monitoring demonstrates more reflux episodes in infants in supine and side positions compared with the prone position, but evidence that the supine position reduces the risk of sudden infant death syndrome has led the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition to recommend supine positioning during sleep. When the infant is awake and observed, prone position and upright carried position can be used to minimize reflux. Lying in the flat supine position and semi-seated positions (e.g., car seats, infant carriers) in the postprandial period are considered provocative positions for GER and therefore should be avoided. The efficacy of positioning for older children is unclear, but some evidence suggests a benefit to left side position and head elevation during sleep. The head should be elevated by elevating the head of the bed, rather than using excess pillows, to avoid abdominal flexion and compression that might worsen reflux.

Pharmacotherapy is directed at ameliorating the acidity of the gastric contents or at promoting their aboral movement and should be considered for those symptomatic infants and children who are either highly suspected or proven to have GERD. Antacids are the most commonly used antireflux therapy and are readily available over the counter. They provide rapid but transient relief of symptoms by acid neutralization. The long-term regular use of antacids cannot be recommended because of side effects of diarrhea (magnesium antacids) and constipation (aluminum antacids) and rare reports of more serious side effects of chronic use.

Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs: cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and ranitidine) are widely used antisecretory agents that act by selective inhibition of histamine receptors on gastric parietal cells. There is a definite benefit of H2RAs in treatment of mild-to-moderate reflux esophagitis. H2RAs have been recommended as first-line therapy because of their excellent overall safety profile, but they are superseded by PPIs in this role, as increased experience with pediatric use and safety, FDA approval, and pediatric formulations and dosing are available.

PPIs (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole) provide the most potent antireflux effect by blocking the hydrogen–potassium adenosine triphosphatase channels of the final common pathway in gastric acid secretion. PPIs are superior to H2RAs in the treatment of severe and erosive esophagitis. Pharmacodynamic studies indicate that children require higher doses of PPIs than adults on a per-weight basis. The use of PPIs to treat infants and children deemed to have GERD on the basis of symptoms is common, however an important systematic review of the efficacy and safety of PPI therapy in pediatric GERD reveals no clear benefit for PPI over placebo use in suspected infantile GERD (crying, arching behavior). Limited pediatric data are available to draw definitive conclusions about potential complications implicated with PPI use, such as respiratory infections, Clostridium difficile infection, bone fractures (noted in adults), hypomagnesemia, and kidney damage.

Prokinetic agents available in the United States include metoclopramide (dopamine-2 and 5-HT3 antagonist), bethanechol (cholinergic agonist), and erythromycin (motilin receptor agonist). Most of these increase LES pressure; some improve gastric emptying or esophageal clearance. None affects the frequency of TLESRs. The available controlled trials have not demonstrated much efficacy for GERD. In 2009, the FDA announced a black box warning for metoclopramide, linking its chronic use (longer than 3 mo) with tardive dyskinesia, the rarely reversible movement disorder. Baclofen is a centrally acting γ-aminobutyric acid agonist that decreases reflux by decreasing TLESRs in healthy adults and in a small number of neurologically impaired children with GERD. Other agents of interest include peripherally acting γ-aminobutyric acid agonists devoid of central side effects, and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonists that are reported to reduce TLESRs but are as yet inadequately studied for this indication in children.

Cisapride is a serotonergic-receptor agonist with prokinetic effect that is only available in the United States through a limited access program because of its cardiac side effects (QT prolongation, dysrhythmias).

Surgery, usually fundoplication, is effective therapy for intractable GERD in children, particularly those with refractory esophagitis or strictures and those at risk for significant morbidity from chronic pulmonary disease. It may be combined with a gastrostomy for feeding or venting. The availability of potent acid-suppressing medication mandates more-rigorous analysis of the relative risks (or costs) and benefits of this relatively irreversible therapy in comparison to long-term pharmacotherapy. Some of the risks of fundoplication include a wrap that is too tight (producing dysphagia or gas-bloat) or too loose (and thus incompetent). Surgeons may choose to perform a tight (360 degrees, Nissen) or variations of a loose (<360 degrees, Thal, Toupet, Boix-Ochoa) wrap, or to add a gastric drainage procedure (pyloroplasty) to improve gastric emptying, based on their experience and the patient's disease. Preoperative accuracy of diagnosis of GERD and the skill of the surgeon are two of the most important predictors of successful outcome. Long-term studies suggest that fundoplications often become incompetent in children, as in adults, with reflux recurrence rates of up to 14% for Nissen and up to 20% for loose wraps (the rates may be highest with laparoscopic procedures); this fact currently combines with the potency of PPI therapy that is available to shift practice toward long-term pharmacotherapy in many cases. Fundoplication procedures may be performed as open operations, by laparoscopy, or by endoluminal (gastroplication) techniques. Pediatric experience is limited with endoscopic application of radiofrequency therapy (Stretta procedure) to a 2-3 cm area of the LES and cardia to create a high-pressure zone to reduce reflux.

Total esophagogastric dissociation is performed in selective neurologically impaired children with repeated failed fundoplications and with severe life-threatening gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Complications of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Seema Khan, Sravan Kumar Reddy Matta

Esophageal: Esophagitis and Sequelae—Stricture, Barrett Esophagus, Adenocarcinoma

Esophagitis can manifest as irritability, arching, and feeding aversion in infants; chest or epigastric pain in older children; and, rarely, as hematemesis, anemia, or Sandifer syndrome at any age. Erosive esophagitis is found in approximately 12% of children with GERD symptoms and is more common in boys, older children, neurologically challenged children, children with severe chronic respiratory disease, and in those with hiatal hernia. Prolonged and severe esophagitis leads to formation of strictures, generally located in the distal esophagus, producing dysphagia, and requiring repeated esophageal dilations and often fundoplication. Long-standing esophagitis predisposes to metaplastic transformation of the normal esophageal squamous epithelium into intestinal columnar epithelium, termed Barrett esophagus, a precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma. A large multicenter prospective study of 840 consecutive children who underwent elective endoscopies reported a 25.7% prevalence for reflux esophagitis, and a mere 0.12% for Barrett esophagus in children without neurologic disorders or tracheoesophageal anomalies. Both Barrett esophagus and adenocarcinoma occur more in white males and in those with increased duration, frequency, and severity of reflux symptoms. This transformation increases with age to plateau in the fifth decade; adenocarcinoma is rare in childhood. Barrett esophagus, uncommon in children, warrants periodic surveillance biopsies, aggressive pharmacotherapy, and fundoplication for progressive lesions.

Nutritional

Esophagitis and regurgitation may be severe enough to induce failure to thrive because of caloric deficits. Enteral (nasogastric or nasojejunal, or percutaneous gastric or jejunal) or parenteral feedings are sometimes required to treat such deficits.

Extraesophageal: Respiratory (“Atypical”) Presentations

GERD should be included in the differential diagnosis of children with unexplained or refractory otolaryngologic and respiratory complaints. GERD can produce respiratory symptoms by direct contact of the refluxed gastric contents with the respiratory tract (aspiration, laryngeal penetration, or microaspiration) or by reflexive interactions between the esophagus and respiratory tract (inducing laryngeal closure or bronchospasm). Often, GERD and a primary respiratory disorder, such as asthma, interact and a vicious cycle between them worsens both diseases. Many children with these extraesophageal presentations do not have typical GERD symptoms, making the diagnosis difficult. These atypical GERD presentations require a thoughtful approach to the differential diagnosis that considers a multitude of primary otolaryngologic (infections, allergies, postnasal drip, voice overuse) and pulmonary (asthma, cystic fibrosis) disorders. Therapy for the GERD must be more intense (usually incorporating a PPI) and prolonged (usually at least 3-6 mo). In these cases a multidisciplinary approach involving otolaryngology, pulmonary for airway disease and gastroenterology for reflux disease is often warranted for specialized diagnostic testing and for optimizing intensive management.

Apnea and Stridor

These upper airway presentations have been linked with GERD in case reports and epidemiologic studies; temporal relationships between them and reflux episodes have been demonstrated in some patients by esophageal pH–multichannel intraluminal impedance studies, and a beneficial response to therapy for GERD provides further support in a number of case series. An evaluation of 1,400 infants with apnea attributed the apnea to GERD in 50%, but other studies have failed to find an association. Apnea and brief resolved unexplained event-like presentation (previously called an “apparent life-threatening event”) caused by reflux is generally obstructive, owing to laryngospasm that may be conceived of as an abnormally intense protective reflex. At the time of such apnea, infants have often been provocatively positioned (supine or flexed seated), have been recently fed, and have shown signs of obstructive apnea, with unproductive respiratory efforts. The evidence suggests that for the large majority of infants presenting with apnea and a brief resolved unexplained event, GERD is not causal. Stridor triggered by reflux generally occurs in infants anatomically predisposed toward stridor (laryngomalacia, micrognathia). Spasmodic croup, an episodic frightening upper airway obstruction, can be an analogous condition in older children. Esophageal pH probe studies might fail to demonstrate linkage of these manifestations with reflux owing to the buffering of gastric contents by infant formula and the episodic nature of the conditions. Pneumograms can fail to identify apnea if they are not designed to identify obstructive apnea by measuring nasal airflow.

Reflux laryngitis and other otolaryngologic manifestations (also known as laryngopharyngeal reflux) can be attributed to GERD. Hoarseness, voice fatigue, throat clearing, chronic cough, pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, and a sensation of globus have been cited. Laryngopharyngeal signs of GERD include edema and hyperemia (of the posterior surface), contact ulcers, granulomas, polyps, subglottic stenosis, and interarytenoid edema. The paucity of well-controlled evaluations of the association contributes to the skepticism with which these associations may be considered. Other risk factors irritating the upper respiratory passages can predispose some patients with GERD to present predominantly with these complaints.

Many studies have reported a strong association between asthma and reflux as determined by history, pH–multichannel intraluminal impedance, endoscopy, and esophageal histology. GERD symptoms are present in an average of 23% (19–80%) of children with asthma as observed in a systematic review of 19 studies examining the prevalence of GERD in asthmatics. The review also reported abnormal pH results in 63%, and esophagitis in 35% of asthmatic children. However, this association does not clarify the direction of causality in individual cases and thus does not indicate which patients with asthma are likely to benefit from anti-GERD therapy. Children with asthma who are particularly likely to have GERD as a provocative factor are those with symptoms of reflux disease, those with refractory or steroid-dependent asthma, and those with nocturnal worsening of asthma. Endoscopic evaluation that discloses esophageal sequelae of GERD provides an impetus to embark on the aggressive (high dose and many months’ duration) therapy of GERD.

Dental erosions constitute the most common oral lesion of GERD, the lesions being distinguished by their location on the lingual surface of the teeth. The severity seems to correlate with the presence of reflux symptoms and the presence of an acidic milieu as the result of reflux in the proximal esophagus and oral cavity. The other common factors that can produce similar dental erosions are juice consumption and bulimia.

Bibliography

Ali Mel-S. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: diagnosis and treatment of a controversial disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol . 2008;8:28–33.

El-Serag HB, Gilger MA, Shub MD, et al. The prevalence of suspected Barrett's esophagus in children and adolescents: a multicenter endoscopic study. Gastrointest Endosc . 2006;64:671–675.

Gilger MA, El-Serag HB, Gold BD, et al. Prevalence of endoscopic findings of erosive esophagitis in children: a population based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr . 2008;47:141–146.

Havemann BD, Henderson CAA, El-Serag HB. The relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and asthma; a systematic review. Gut . 2007;56:1654–1664.

Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB, Shub M, et al. Barrett's esophagus in children and adolescents without neurodevelopmental or tracheoesophageal abnormalities: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc . 2011;73(5):875–880.

Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett's oesophagus. Lancet . 2009;373:850–858.

Shaheen NJ, Sharma P, Overholt BF, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med . 2009;360:2277–2288.

Slocum C, Hibbs AM, Martin RJ, et al. Infant apnea and gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review and framework for further investigation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep . 2007;9:219–224.

Smits MJ, van Wilk MP, et al. Association between gastroesophageal reflux and pathologic apneas in infants: a systematic review. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016;26(11):1527–1538.

Thakkar K, Boatright RO, Gilger MA, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in children with asthma: a systematic review. Pediatrics . 2010;125(4):925–930.

Tolia V, Vandenplas Y. Systematic review: the extra-oesophageal symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther . 2009;29:258–272.

Vaezi MF. Laryngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep . 2008;10:271–277.

Valusek PA, St Peter SD, Tsao K, et al. The use of fundoplication for prevention of apparent life-threatening events. J Pediatr Surg . 2007;42:1022–1024.