Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Pill Esophagitis, and Infective Esophagitis

Seema Khan

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic esophageal disorder characterized by esophageal dysfunction and infiltration of the esophageal epithelium by ≥15 eosinophils per high-power field. The diagnostic criteria has recently been updated as a result of the consensus conference on Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE). The diagnosis of EoE should be considered in the clinical presentation of esophageal dysfunction, associated with esophageal epithelial infiltration of at least 15 eosinophils (eos) per high power field (hpf) or ~60 eos per mm2 , and after a careful evaluation of non-EoE disorders. Proton pump inhibitors should be considered as another treatment option rather than a diagnostic criterion to differentiate from GERD. EoE is a global disease, with incidence and prevalence rates in children 5 and 29.5 per 100,000. While infants and toddlers present commonly with vomiting, feeding problems, and poor weight gain, older children and adolescents usually experience solid food dysphagia with occasional food impactions (Fig. 350.1 ) or strictures and may complain of heartburn, chest or epigastric pain. Most patients are male. The mean age at diagnosis is 7 yr (range: 1-17 yr), and the duration of symptoms is 3 yr. Many patients have other atopic diseases (or a positive family history) and associated food allergies; laboratory abnormalities can include peripheral eosinophilia and elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels. The pathogenesis involves mainly T-helper type 2 cytokine-mediated (interleukin 5 and 13) pathways leading to production of a potent eosinophil chemoattractant, eotaxin-3, by esophageal epithelium. The eosinophilic esophagitis endoscopic reference score (EREFS ), based on commonly observed features of edema (E), rings (R; Fig. 350.2 ), exudates (E; see Fig. 350.2 ), furrows (F; Fig. 350.3 ), strictures (S), has utility in diagnosis and monitoring response to treatment. Esophageal histology reveals profound eosinophilia, with a currently acceptable cutoff for diagnosis chosen at ≥15 to 20/high-power field. Up to 30% children with EoE have grossly normal esophageal mucosa. EoE is differentiated from gastroesophageal reflux disease by concurrent atopic diseases, its general lack of erosive esophagitis, its greater eosinophil density, and its normal esophageal pH-multichannel intraluminal impedance results. A favorable response to proton pump inhibitor therapy should no longer be considered diagnostic of gastroesophageal reflux disease, as approximately two-thirds of children with EoE also demonstrate histologic response and constitute a proton pump inhibitor–responsive EoE (PPI-REF) group. Observations in children and adults with EoE are notable for striking similarities between PPI responders and PPI non-responders with regard to symptoms, histology, molecular signature, and mechanistic features. This response may be because of an acid suppressive action or down regulation of Th-2 allergic cell pathway, an antieosinophil effect of the PPI class that is mediated by inhibition of eotaxin-3 secretion. Evaluation of EoE should include a search for food (aerodigestive) and environmental allergies via skin prick (IgE mediated) and patch (non–IgE mediated) tests to guide decisions regarding dietary elimination and future food challenges.

Treatment involves dietary restrictions that take one of 3 forms: elimination diets guided by circumstantial evidence and food allergy test results; “6 food elimination diet” removing the major food allergens (milk, soy, wheat, egg, peanuts and tree nuts, seafood); and elemental diet composed exclusively of an amino acid-based formula. Elimination diets are generally successful, with highest histologic response observed in nearly 91% on elemental diet and in 72% to empiric dietary elimination. Targeted elimination diets guided by multimodal allergy testing are comparable to empiric food elimination and hence lead to the argument against rigorous testing. The major drawbacks of dietary therapy lie in its cost, difficult access, and lower quality of life, any or all of which influence adherence and outcome.

Topically acting swallowed corticosteroids (fluticasone without spacer, viscous budesonide suspension) have been used successfully for those who refuse, fail to adhere, or have a poor response to restricted diets. Histologic remission is observed in 65-77% children and adults treated with fluticasone for 3 mo. Histologic recurrence after discontinuation of fluticasone is common, and emphasizes the need for maintenance therapy, and an approach that would carefully balance the risks of adrenocortical insufficiency as well as, bone demineralization and fungal infections against the risk of EoE evolution from an inflammatory to fibrostenotic disease producing esophageal stenosis and strictures. Therapies under investigation include anti-interleukin-5 antibodies (mepolizumab, reslizumab). Patients require periodic endoscopy and histologic reassessment for the most reliable monitoring of response to treatment, particularly given a significant disconnect between symptoms and histology in the evolution of the disease. Expert clinical guidelines stress long-term studies to develop systematic treatment and best follow-up protocols.

Infective Esophagitis

Uncommon, and most often affecting immunocompromised children, infective esophagitis is caused by fungal agents, such as Candida albicans and Torulopsis glabrata; viral agents, such as herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, HIV, and varicella zoster; and, rarely, bacterial infections, including diphtheria and tuberculosis, or parasites. The typical presenting signs and symptoms are odynophagia, dysphagia, and retrosternal or chest pain; there may also be fever, nausea, and vomiting. Candida is the leading cause of infective esophagitis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised children and presents with concurrent oropharyngeal infection in the majority of immunocompromised patients. It may also be an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients, notably in those with EoE receiving topical swallowed corticosteroids. Esophageal viral infections can also manifest in immunocompetent hosts as an acute febrile illness. Infectious esophagitis, like other forms of esophageal inflammation, occasionally progresses to esophageal stricture. Diagnosis of infectious esophagitis is made by endoscopy, usually notable for white plaques in candida, multiple superficial ulcers or volcano ulcers in herpes simplex virus, and single deep ulcer in cytomegalovirus. Histopathologic examination solidifies the diagnosis with the detection of yeast and pseudohyphae in Candida; tissue invasion distinguishes esophagitis from mere colonization. Multinucleated giant cells with intranuclear Cowdry type A (eosinophilic) and type B (ground glass appearance) inclusions in HSV, and both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions producing an owl's eye appearance in CMV are typically described. Adding polymerase chain reaction, tissue-viral culture, and immunocytochemistry enhances the diagnostic sensitivity and precision. Treatment is with appropriate antimicrobial agents; azole therapy, particularly oral fluconazole for Candida; oral acyclovir for HSV, and oral valganciclovir for CMV, or alternatively intravenous ganciclovir in severe CMV disease.

Pill Esophagitis

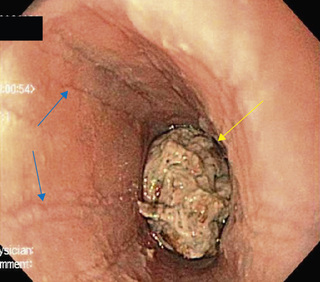

This acute injury is produced by contact with a damaging agent. Medications implicated in pill esophagitis include tetracycline, doxycycline, potassium chloride, ferrous sulfate, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, cloxacillin, and alendronate (Table 350.1 ). Most often the offending tablet is ingested at bedtime with inadequate water. This practice often produces acute discomfort followed by progressive retrosternal pain, odynophagia, and dysphagia. Endoscopy shows a focal lesion often localized to one of the anatomic narrowed regions of the esophagus or to an unsuspected pathologic narrowing (Fig. 350.4 ). Treatment is supportive; lacking much evidence, sucralfate, antacids, topical anesthetics, and bland or liquid diets are often used. The offending pill may be restarted after complete resolution of symptoms, if deemed necessary, though with clear emphasis on ingestion with adequate volume of water, usually at least 4 oz.

Table 350.1

Medications Commonly Associated With Esophagitis or Esophageal Injury

| ANTIBIOTICS |

| ANTIVIRAL AGENTS |

| BISPHOSPHONATES |

| CHEMOTHERAPEUTIC AGENTS |

| OTHER MEDICATIONS |

From Katzka DA: Esophageal disorders caused by medications, trauma, and infection. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors: Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease , ed 10, 2016, Box 46.1.