Surgical Conditions of the Anus and Rectum

Anorectal Malformations

Christina M. Shanti

Keywords

- Imperforate anus

- Perineal fistula

- Fourchette fistula

- Rectovaginal fistula

- Cloaca

- Rectourethral fistula

- Caudal regression

- Anal stenosis

- Anterior ectopic anus

- Rectal atresia

- Currarino triad

- Tethered Cord

- PSARP: Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty

- Fecal continence

- ACE Antegrade continence enema

- MACE Malone antegrade continence enema

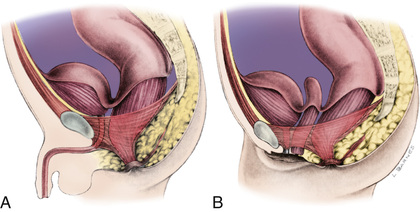

To fully understand the spectrum of anorectal anomalies, it is necessary to consider the importance of the sphincter complex, a mass of muscle fibers surrounding the anorectum (Fig. 371.1 ). This complex is the combination of the puborectalis, levator ani, external and internal sphincters, and the superficial external sphincter muscles, all meeting at the rectum. Anorectal malformations are defined by the relationship of the rectum to this complex and include varying degrees of stenosis to complete atresia. The incidence is 1/3,000 live births. Significant long-term concerns focus on bowel control and urinary and sexual functions.

Embryology

The hindgut forms early as the part of the primitive gut tube that extends into the tail fold in the 2nd wk of gestation. At about day 13, it develops a ventral diverticulum, the allantois, or primitive bladder. The junction of allantois and hindgut becomes the cloaca, into which the genital, urinary, and intestinal tubes empty. This is covered by a cloacal membrane. The urorectal septum descends to divide this common channel by forming lateral ridges, which grow in and fuse by the middle of the 7th wk. Opening of the posterior portion of the membrane (the anal membrane) occurs in the 8th wk. Failures in any part of these processes can lead to the clinical spectrum of anogenital anomalies.

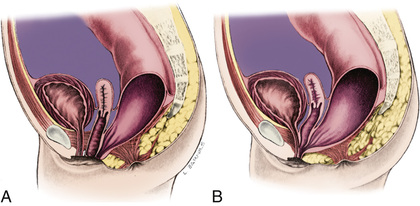

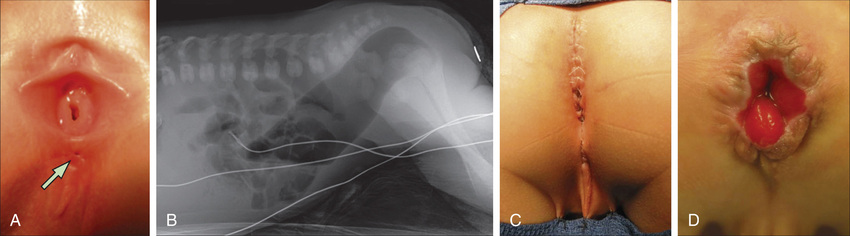

Imperforate anus can be divided into low lesions, where the rectum has descended through the sphincter complex, and high lesions, where it has not. Most patients with imperforate anus have a fistula. There is a spectrum of malformation in males and females. In males, low lesions usually manifest with meconium staining somewhere on the perineum along the median raphe (Fig. 371.2A ). Low lesions in females also manifest as a spectrum from an anus that is only slightly anterior on the perineal body to a fourchette fistula that opens on the moist mucosa of the introitus distal to the hymen (Fig. 371.3A ). A high imperforate anus in a male has no apparent cutaneous opening or fistula, but it usually has a fistula to the urinary tract, either the urethra or the bladder (see Fig. 371.2B ). Although there is occasionally a rectovaginal fistula, in females, high lesions are usually cloacal anomalies in which the rectum, vagina, and urethra all empty into a common channel or cloacal stem of varying length (see Fig. 371.3B ). The interesting category of males with imperforate anus and no fistula occurs mainly in children with trisomy 21. The most common lesions are the rectourethral bulbar fistula in males and the rectovestibular fistula in females; the 2nd most common lesion in both sexes is the perianal fistula (Fig. 371.4 ).

Associated Anomalies

There are many anomalies associated with anorectal malformations (Table 371.1 ). The most common are anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract in conjunction with abnormalities of the sacrum. This complex is often referred to as caudal regression syndrome . Males with a rectovesical fistula and patients with a persistent cloaca have a 90% risk of urologic defects. Other common associated anomalies are cardiac anomalies and esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula. These can cluster in any combination in a patient. When combined, they are often accompanied by abnormalities of the radial aspect of the upper extremity and are termed the VACTERL (v ertebral, a nal, c ardiac, t racheal, e sophageal, r enal, l imb) anomalad.

Table 371.1

| GENITOURINARY |

| VERTEBRAL |

| CARDIOVASCULAR |

| GASTROINTESTINAL |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM |

Anorectal malformations, particularly anal stenosis and rectal atresia, can also present as Currarino triad, which includes sacral agenesis, presacral mass, and anorectal stenosis. These patients present with a funnel appearing anus, have sacral bony defects on plain x-ray, and have a presacral mass (teratoma, meningocele, dermoid cyst, enteric cyst) on exam or imaging. It is an autosomal dominant disorder due in most patients to a mutation in the MNX1 gene.

A good correlation exists between the degree of sacral development and future function. Patients with an absent sacrum usually have permanent fecal and urinary incontinence. Spinal abnormalities and different degrees of dysraphism are often associated with these defects. Tethered cord occurs in approximately 25% of patients with anorectal malformations. Untethering of the cord can lead to improved urinary and rectal continence in some patients, although it seldom reverses established neurologic defects. The diagnosis of spinal defects can be screened for in the first 3 mo of life by spinal ultrasound, although MRI is the imaging method of choice if a lesion is suspected. In older patients, MRI is needed.

Manifestations and Diagnosis

Low Lesions

Examination of a newborn includes the inspection of the perineum. The absence of an anal orifice in the correct position leads to further evaluation. Mild forms of imperforate anus are often called anal stenosis or anterior ectopic anus . These are typically cases of an imperforate anus with a perineal fistula. The normal position of the anus on the perineum is approximately halfway (0.5 ratio) between the coccyx and the scrotum or introitus. Although symptoms, primarily constipation, have been attributed to anterior ectopic anus (ratio: <0.34 in females, <0.46 in males), many patients have no symptoms.

If no anus or fistula is visible, there may be a low lesion or covered anus . In these cases, there are well-formed buttocks and often a thickened raphe or bucket handle . After 24 hr, meconium bulging may be seen, creating a blue or black appearance. In these cases, an immediate perineal procedure can often be performed, followed by a dilation program.

In a male, the perineal (cutaneous) fistula can track anteriorly along the median raphe across the scrotum and even down the penile shaft. This is usually a thin track, with a normal rectum often just a few millimeters from the skin. Extraintestinal anomalies are seen in <10% of these patients.

In a female, a low lesion enters the vestibule or fourchette (the moist mucosa outside the hymen but within the introitus). In this case, the rectum has descended through the sphincter complex. Children with a low lesion can usually be treated initially with perineal manipulation and dilation. Visualizing these low fistulas is so important in the evaluation and treatment that one should avoid passing a nasogastric tube for the first 24 hr to allow the abdomen and bowel to distend, pushing meconium down into the distal rectum.

High Lesions

In a male with a high imperforate anus, the perineum appears flat. There may be air or meconium passed via the urethra when the fistula is high, entering the bulbar or prostatic urethra, or even the bladder. In rectobulbar urethral fistulas (the most common in males), the sphincter mechanism is satisfactory, the sacrum may be underdeveloped, and an anal dimple is present. In rectoprostatic urethral fistulas , the sacrum is poorly developed, the scrotum may be bifid, and the anal dimple is near the scrotum. In rectovesicular fistulas , the sphincter mechanism is poorly developed, and the sacrum is hypoplastic or absent. In males with trisomy 21, all the features of a high lesion may be present, but there is no fistula, the sacrum and sphincter mechanisms are usually well developed, and the prognosis is good.

In females with high imperforate anus, there may be the appearance of a rectovaginal fistula. A true rectovaginal fistula is rare. Most are either the fourchette fistulas described earlier or are forms of a cloacal anomaly.

Persistent Cloaca

In persistent cloaca, the embryologic stage persists in which the rectum, urethra, and vagina communicate in a common orifice, the cloaca. It is important to realize this, because the repair often requires repositioning the urethra and vagina as well as the rectum. Children of both sexes with a high lesion require a colostomy before repair.

Rectal Atresia

Rectal atresia is a rare defect occurring in only 1% of anorectal anomalies. It has the same characteristics in both sexes. The unique feature of this defect is that affected patients have a normal anal canal and a normal anus. The defect is often discovered while rectal temperature is being taken. An obstruction is present approximately 2 cm above the skin level. These patients need a protective colostomy. The functional prognosis is excellent because they have a normal sphincteric mechanism (and normal sensation), which resides in the anal canal.

Approach to the Patient

Evaluation includes identifying associated anomalies (see Table 371.1 ). Careful inspection of the perineum is important to determine the presence or absence of a fistula. If the fistula can be seen there, it is a low lesion. The invertogram or upside-down x-ray is of little value, but a prone crosstable lateral plain x-ray at 24 hr of life (to allow time for bowel distention from swallowed air) with a radiopaque marker on the perineum can demonstrate a low lesion by showing the rectal gas bubble <1 cm from the perineal skin (see Fig. 371.4 ). A plain x-ray of the entire sacrum, including both iliac wings, is important to identify sacral anomalies and the adequacy of the sacrum. An abdominal-pelvic ultrasound and voiding cystourethrogram must be performed. The clinician should also pass a nasogastric tube to identify esophageal atresia and should obtain an echocardiogram. In males with a high lesion, the voiding cystourethrogram often identifies the rectourinary fistula. In females with a high lesion, more invasive evaluation, including vaginogram and endoscopy, is often necessary for careful detailing of the cloacal anomaly.

Good clinical evaluation and a urinalysis provide enough data in 80–90% of male patients to determine the need for a colostomy. Voluntary sphincteric muscles surround the most distal part of the bowel in cases of perineal and rectourethral fistulas, and the intraluminal bowel pressure must be sufficiently high to overcome the tone of those muscles before meconium can be seen in the urine or on the perineum. The presence of meconium in the urine and a flat bottom are considered indications for the creation of a colostomy. Clinical findings consistent with the diagnosis of a perineal fistula represent an indication for an anoplasty without a protective colostomy. Ultrasound is valuable not only for the evaluation of the urinary tract, but it can also be used to investigate spinal anomalies in the newborn and to determine how close to the perineum the rectum has descended.

More than 90% of the time, the diagnosis in females can be established on perineal inspection. The presence of a single perineal orifice is a cloaca. A palpable pelvic mass (hydrocolpos) reinforces this diagnosis. A vestibular fistula is diagnosed by careful separation of the labia, exposing the vestibule. The rectal orifice is located immediately in front of the hymen within the female genitalia and in the vestibule. A perineal fistula is easy to diagnose. The rectal orifice is located somewhere between the female genitalia and the center of the sphincter and is surrounded by skin. Less than 10% of these patients fail to pass meconium through the genitalia or perineum after 24 hr of observation. Those patients can require a prone crosstable lateral film.

Operative Repair

Sometimes a perineal fistula, if it opens in good position, can be treated by simple dilation. Hegar dilators are employed, starting with a No. 5 or 6 and letting the baby go home when the mother can use a No. 8. Twice-daily dilatations are done at home, increasing the size every few weeks until a No. 14 is achieved. By 1 yr of age, the stool is usually well formed and further dilation is not necessary. By the time No. 14 is reached, the examiner can usually insert a little finger. If the anal ring is soft and pliable, dilation can be reduced in frequency or discontinued.

Occasionally, there is no visible fistula, but the rectum can be seen to be filled with meconium bulging on the perineum, or a covered anus is otherwise suspected. If confirmed by plain x-ray or ultrasound of the perineum that the rectum is <1 cm from the skin, the clinician can do a minor perineal procedure to perforate the skin and then proceed with dilation or do a simple perineal anoplasty.

When the fistula orifice is very close to the introitus or scrotum, it is often appropriate to move it back surgically. This also requires postoperative dilation to prevent stricture formation. This procedure can be done any time from the newborn period to 1 yr. It is preferable to wait until dilatations have been done for several weeks and the child is bigger. The anorectum is a little easier to dissect at this time. The posterior sagittal approach of Peña is used, making an incision around the fistula and then in the midline to the site of the posterior wall of the new location. The dissection is continued in the midline, using a muscle stimulator to be sure there is adequate muscle on both sides. The fistula must be dissected cephalad for several centimeters to allow posterior positioning without tension. If appropriate, some of the distal fistula is resected before the anastomosis to the perineal skin.

In children with a high lesion, a double-barrel colostomy is performed. This effectively separates the fecal stream from the urinary tract. It also allows the performance of an augmented pressure colostogram before repair to identify the exact position of the distal rectum and the fistula. The definitive repair or posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) is performed at about 1 yr of age. A midline incision is made, often splitting the coccyx and even the sacrum. Using a muscle stimulator, the surgeon stays strictly in the midline and divides the sphincter complex and identifies the rectum. The rectum is then opened in the midline and the fistula is identified from within the rectum. This allows a division of the fistula without injury to the urinary tract. The rectum is then dissected proximally until enough length is gained to suture it to an appropriate perineal position. The muscles of the sphincter complex are then sutured around (and especially behind) the rectum.

Other operative approaches (such as an anterior approach) are used, but the most popular procedure is by laparoscopy. This operation allows division of the fistula under direct visualization and identification of the sphincter complex by transillumination of perineum. Other imaging techniques in the management of anorectal malformations include 3D endorectal ultrasound, intraoperative MRI, and colonoscopy-assisted PSARPs, which may help perform a technically better operation. None of these other procedures or innovations has demonstrated improved outcomes.

A similar procedure can be done for female high anomalies with variations to deal with separating the vagina and rectum from within the cloacal stem. When the stem is longer than 3 cm, this is an especially difficult and complex procedure.

Usually the colostomy can be closed 6 wk or more after the PSARP. Two weeks after any anal procedure, twice-daily dilatations are performed by the family. By doing frequent dilatations, each one is not so painful and there is less tissue trauma, inflammation, and scarring.

Outcome

The ability to achieve rectal continence depends on both motor and sensory elements. There must be adequate muscle in the sphincter complex and proper positioning of the rectum within the complex. There must also be intact innervation of the complex and of sensory elements, as well as the presence of these sensory elements in the anorectum. Patients with low lesions are more likely to achieve true continence. They are also, however, more prone to constipation, which leads to overflow incontinence. It is very important that all these patients are followed closely, and that the constipation and anal dilation are well managed until toilet training is successful. Tables 371.2 and 371.3 outline the results of continence and constipation in relation to the malformation encountered.

Table 371.2

Types of Anorectal Malformation by Sex

| MALE (PERCENTAGE CHANCE OF BOWEL CONTROL * ) |

| FEMALE (PERCENTAGE CHANCE OF BOWEL CONTROL * ) |

|

• Rectovaginal fistula (rare anomaly) † |

|

• Cloaca (70%) ‡ |

* Provided patients have a normal sacrum, no tethered cord, and they receive a technically correct operation without complications.

† Rectovaginal anomalies are extremely unusual; usually their prognosis is like rectovestibular fistula.

‡ Cloaca represents a spectrum; those with a common channel length <3 cm have the best functional prognosis.

From Bischoff A, Bealer J, Pená A: Controversies in anorectal malformations, Lancet Child/Adolesc 1:323–330, 2017 (Panel p. 323).

Table 371.3

Modified from Levitt MA, Peña A: Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations, Curr Opin Pediatr 17:394–401, 2005.

Children with high lesions, especially males with rectoprostatic urethral fistulas and females with cloacal anomalies, have a poorer chance of being continent, but they can usually achieve a socially acceptable defecation (without a colostomy) pattern with a bowel management program. Often, the bowel management program consists of a daily enema to keep the colon empty and the patient clean until the next enema. If this is successful, an antegrade continence enema (ACE) procedure, sometimes called the Malone or Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) procedure, can improve the patient's quality of life. These procedures provide access to the right colon either by bringing the appendix out the umbilicus in a nonrefluxing fashion or by putting a plastic button in the right lower quadrant to access the cecum. The patient can then sit on the toilet and administer the enema through the ACE, thus flushing out the entire colon. Antegrade regimens can produce successful 24 hr cleanliness rates of up to 95%. Of special interest is the clinical finding that most patients improve their control with growth. Patients who wore diapers or pull-ups to primary school are often in regular underwear by high school. Some groups have taken advantage of this evidence of psychologic influences to initiate behavior modification early with good results.

Bibliography

Akkoyun J, Akbiyik F, Soylu SG. The use of digital photos and video images taken by a parent in the diagnosis of anal swelling and anal protrusions in children with normal physical examination. J Pediatr Surg . 2011;46:2132–2134.

Bischoff A, Bealer J, Pená A. Controversies in anorectal malformations. Lancet Child Adolesc Health . 2017;1:323–330.

Georgeson KE, Inge TH, Albanese CT. Laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus—a new technique. J Pediatr Surg . 2000;35:927–930.

Hashish MS, Dawoud HH, Hirschl RB, et al. Long-term functional outcome and quality of life in patients with high imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg . 2010;45:224–230.

Jonker JE, Trzpis M, Broens PMA. Underdiagnosis of mild congenital anorectal malformations. J Pediatr . 2017;186:101–104.

Lee SC, Chun YS, Jung SE, et al. Currarino triad: anorectal malformation, sacral bony abnormality, and presacral mass—a review of 11 cases. J Pediatr Surg . 1997;32:58.

Levitt MA, Haber HP, Seitz G, et al. Transperineal sonography for determination of the type of imperforate anus. AJR Am J Roentgenol . 2007;189:1525–1529.

Levitt MA, Peña A. Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2005;17:394–401.

Mattix KD, Novotny NM, Shelley AA, et al. Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) for fecal incontinence in imperforate anus improves quality of life. Pediatr Surg Int . 2007;23:1175–1177.

Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Imperforate anus: long- and short-term outcome. Semin Pediatr Surg . 2008;17:79–89.

Sigalet DL, Laberge JM, Adolph VR, et al. The anterior sagittal approach for high imperforate anus: a simplification of the mollard approach. J Pediatr Surg . 1996;31:625–629.

Simpson JA, Banerjea A, Scholefield JH. Management of anal fistula. BMJ . 2012;345:e5836.

Spingford LR, Connor MJ, Jones K, et al. Prevalence of active long-term problems in patients with anorectal malformations: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum . 2016;59:570–580.

Vick LR, Gosche JR, Boulanger SC, et al. Primary laparoscopic repair of high imperforate anus in neonatal males. J Pediatr Surg . 2007;42:1877–1881.

Anal Fissure

Christina M. Shanti

Anal fissure is a laceration of the anal mucocutaneous junction. It is an acquired lesion of unknown etiology. While likely secondary to the forceful passage of a hard stool, it is mainly seen in infants younger than 1 yr of age when the stool is frequently quite soft. Fissures may be the consequence and not the cause of constipation.

Clinical Manifestations

A history of constipation is often described, with a recent painful bowel movement corresponding to the fissure formation after passing of hard stool. The patient then voluntarily retains stool to avoid another painful bowel movement, exacerbating the constipation, resulting in harder stools. Complaints of pain on defecation and bright red blood on the surface of the stool are often elicited.

The diagnosis is established by inspection of the perineal area. The infant's hips are held in acute flexion, the buttocks are separated to expand the folds of the perianal skin, and the fissure becomes evident as a minor laceration. Often a small skin appendage is noted peripheral to the lesion. This skin tag represents epithelialized granulomatous tissue formed in response to chronic inflammation. Findings on rectal examination can include hard stool in the ampulla and rectal spasm.

Treatment

The parents must be counseled as to the origin of the laceration and the mechanism of the cycle of constipation. The goal is to ensure that the patient has soft stools to avoid overstretching the anus. The healing process can take several weeks or even several months. A single episode of impaction with passing of hard stool can exacerbate the problem. Treatment requires that the primary cause of the constipation be identified. The use of dietary and behavioral modification and a stool softener is indicated. Parents should titrate the dose of the stool softener based on the patient's response to treatment. Stool softening is best done by increasing water intake or using an oral polyethylene glycolate such as MiraLAX or GlycoLax. Surgical intervention, including stretching of the anus, “internal” anal sphincterotomy, or excision of the fissure, is not indicated or supported by scientific evidence.

Chronic anal fissures in older patients are associated with constipation, prior rectal surgery, Crohn disease, and chronic diarrhea. They are managed initially like fissures in infants, with stool softeners with the addition of sitz baths. Topical 0.2% glyceryl trinitrate reduces anal spasm and heals fissures, but it is often associated with headaches. Calcium channel blockers, such as 2% diltiazem ointment and 0.5% nifedipine cream, are more effective and cause fewer headaches than glyceryl trinitrate. Injection of botulinum toxin from 1.25 to 25 units is also effective and probably chemically replicates the action of internal sphincterotomy, which is the most effective treatment in adults, although seldom used in children.

Bibliography

Cevik M, Boleken ME, Koruk I, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing the efficacy of diltiazem, glyceryl trinitrate, and lidocaine for the treatment of anal fissure in children. Pediatr Surg Int . 2012;28:411–416.

Golfam F, Golfam P, Khalaj A, et al. The effect of topical nifedipine in treatment of chronic anal fissure. Acta Med Iran . 2010;48:295–299.

Husberg B, Malmborg P, Strigård K. Treatment with botulinum toxin in children with chronic anal fissure. Eur J Pediatr Surg . 2009;19:290–292.

Perianal Abscess and Fistula

Christina M. Shanti

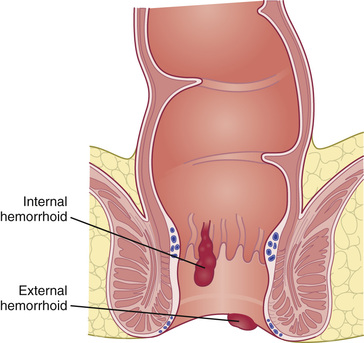

Perianal abscesses usually manifest in infancy and are of unknown etiology. Fistula appears to be secondary to the abscess rather than a cause. Links to congenitally abnormal crypts of Morgagni have been proposed, suggesting that deeper crypts (3-10 mm rather than the normal 1-2 mm) lead to trapped debris and cryptitis (Fig. 371.5 ).

Conditions associated with the risk of an anal fistula include Crohn disease, tuberculosis, pilonidal disease, hidradenitis, HIV, trauma, foreign bodies, dermal cysts, sacrococcygeal teratoma, actinomycosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and radiotherapy.

The most common organisms isolated from perianal abscesses are mixed aerobic (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus) and anaerobic (Bacteroides spp., Clostridium, Veillonella ) flora. A total of 10–15% yield pure growth of E. coli, S. aureus, or Bacteroides fragilis. There is a strong male predominance in those affected who are younger than 2 yr of age. This imbalance corrects in older patients, where the etiology shifts to associated conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, leukemia, or immunocompromised states.

Clinical Manifestations

In younger patients, symptoms are usually mild and can consist of low-grade fever, mild rectal pain, and an area of perianal cellulitis. Often these spontaneously drain and resolve without treatment. In older patients with underlying predisposing conditions, the clinical course may be more serious. A compromised immune system can mask fever and allow rapid progression to toxicity and sepsis. Abscesses in these patients may be deeper in the ischiorectal fossa or even supralevator in contrast to those in younger patients, which are usually adjacent to the involved crypt.

Progression to fistula in patients with perianal abscesses occurs in up to 85% of cases and usually manifests with drainage from the perineal skin or multiple recurrences. Similar to abscess formation, fistulas have a strong male predominance. Histologic evaluation of fistula tracts typically reveals an epithelial lining of stratified squamous cells associated with chronic inflammation. It might also reveal an alternative etiology such as the granulomas of Crohn disease or even evidence of tuberculosis.

Treatment

Treatment is rarely indicated in infants with no predisposing disease because the condition is often self-limited. Even in cases of fistulization, conservative management (observation) is advocated because the fistula often disappears spontaneously. In one study, 87% of fistulas (in 97/112 infants) closed after a mean of 5 mo of observation and conservative management. Antibiotics are not useful in these patients. When dictated by patient discomfort, abscesses may be drained under local anesthesia. Fistulas requiring surgical intervention may be treated by fistulotomy (unroofing or opening), fistulectomy (excision of the tract leaving it open to heal secondarily), or placement of a seton (heavy suture threaded through the fistula, brought out the anus and tied tightly to itself). In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, topical tacrolimus has been effective.

Older children with predisposing diseases might also do well with minimal intervention. If there is little discomfort and no fever or other sign of systemic illness, local hygiene and antibiotics may be best. The danger of surgical intervention in an immunocompromised patient is the creation of an even larger, nonhealing wound. There certainly are such patients with serious systemic symptoms who require more aggressive intervention along with treatment of the predisposing condition. Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage must be administered, and wide excision and drainage are mandatory in cases involving sepsis and expanding cellulitis.

Fistulas in older patients are mainly associated with Crohn disease, a history of pull-through surgery for the treatment of Hirschsprung disease, or, in rare cases, tuberculosis. Those fistulas are often resistant to therapy and require treatment of the predisposing condition.

Complications of treatment include recurrence and, rarely, incontinence.

Bibliography

Chang HK, Ryu JG, Oh JT. Clinical characteristics and treatment of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano in infants. J Pediatr Surg . 2010;45:1832–1836.

Medical Letter. Nitroglycerin ointment (Rectiv) for anal fissure. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2012;54:23–24.

Othman I. Bilateral versus posterior injection of botulinum toxin in the internal anal sphincter for the treatment of acute anal fissure. S Afr J Surg . 2010;48:20–22.

Pallin DJ, Egan DJ, Pelletier AJ, et al. Increased US emergency department visits for skin and soft tissue infections, and changes in antibiotic choices, during the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Ann Emerg Med . 2008;51:291–298.

Wong KK, Wu X, Chan IH, et al. Evaluation of defecative function 5 years or longer after laparoscopic-assisted pull-through for imperforate anus. J Pediatr Surg . 2011;46:2313–2315.

Hemorrhoids

Christina M. Shanti

Hemorrhoidal disease occurs in both children and adolescents, often related to a diet deficient in fiber and poor hydration. In younger children, the presence of hemorrhoids should also raise the suspicion of portal hypertension. A third of patients with hemorrhoids require treatment.

Clinical Manifestations

Presentation depends on the location of the hemorrhoids. External hemorrhoids occur below the dentate line (see Figs. 371.5 and 371.6 ) and are associated with extreme pain and itching, often due to acute thrombosis. Internal hemorrhoids are located above the dentate line and manifest primarily with bleeding, prolapse, and occasional incarceration.

Treatment

In most cases, conservative management with dietary modification, decreased straining, and avoidance of prolonged time spent sitting on the toilet results in resolution of the condition. Discomfort may be treated with topical analgesics or anti-inflammatories such as Anusol (pramoxine) and Anusol-HC (hydrocortisone) and sitz baths. The natural course of thrombosed hemorrhoid involves increasing pain, which peaks at 48-72 hr, with gradual remission as the thrombus organizes and involutes over the next 1-2 wk. In cases where the patient with external hemorrhoids presents with excruciating pain soon after the onset of symptoms, thrombectomy may be indicated. This is best accomplished with local infiltration of bupivacaine 0.25% with epinephrine 1:200,000, followed by incision of the vein or skin tag and extraction of the clot. This provides immediate relief; recurrence is rare and further follow-up is unnecessary.

Internal hemorrhoids can become painful when prolapse leads to incarceration and necrosis. Pain usually resolves with reduction of hemorrhoidal tissue. Surgical treatment is reserved for patients failing conservative management. Techniques described in adults include excision, rubber banding, stapling, and excision using the LigaSure device. Complications are rare (<5%) and include recurrence, bleeding, infection, nonhealing wounds, and fistula formation.

Rectal Mucosal Prolapse

Christina M. Shanti

Rectal mucosal prolapse is the exteriorization of the rectal mucosa through the anus. In the unusual occurrence when all the layers of the rectal wall are included, it is called procidentia or rectocele . Most cases of rectal tissue protruding through the anus are prolapse and not polyps, hemorrhoids, intussusception, or other tissue.

Most cases of prolapse are idiopathic. The onset is often between 1 and 5 yr of age. It usually occurs when the child begins standing and then resolves by approximately 3-5 yr of age when the sacrum has taken its more adult shape and the anal lumen is oriented posteriorly. Thus the entire weight of the abdominal viscera is not pushing down on the rectum, as it is earlier in development.

Other predisposing factors include intestinal parasites (particularly in endemic areas), malnutrition, diarrhea, ulcerative colitis, pertussis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, meningocele (more often associated with procidentia owing to the lack of perineal muscle support), cystic fibrosis, and chronic constipation. Patients treated surgically for imperforate anus can also have varying degrees of rectal mucosal prolapse. This is particularly common in patients with poor sphincteric development. Rectal prolapse is also seen with higher incidence in patients with mental issues and behavior problems. These patients are particularly difficult to manage and are more likely to fail medical treatment.

Clinical Manifestations

Rectal mucosal prolapse usually occurs during defecation, especially during toilet training. Reduction of the prolapse may be spontaneous or accomplished manually by the patient or parent. In severe cases, the prolapsed mucosa becomes congested and edematous, making it more difficult to reduce. Rectal prolapse is usually painless or produces mild discomfort. If the rectum remains prolapsed after defecation, it can be traumatized by friction with undergarments, with resultant bleeding, wetness, and potentially ulceration. The appearance of the prolapse varies from bright red to dark red and resembles a beehive. It can be as long as 10-12 cm. See Chapter 372 for a distinction from a prolapsed polyp.

Treatment

Initial evaluation should include tests to rule out any predisposing conditions, especially cystic fibrosis and sacral root lesions. Reduction of protrusion is aided by pressure with warm compresses. An easy method of reduction is to cover the finger with a piece of toilet paper, introduce it into the lumen of the mass, and gently push it into the patient's rectum. The finger is then immediately withdrawn. The toilet paper adheres to the mucous membrane, permitting release of the finger. The paper, when softened, is later expelled.

Conservative treatment consists of careful manual reduction of the prolapse after defecation, attempts to avoid excessive pushing during bowel movements (with patient's feet off the floor), use of laxatives and stool softeners to prevent constipation, avoidance of inflammatory conditions of the rectum, and treatment of intestinal parasitosis when present. If all this fails, surgical treatment may be indicated. Existing surgical options are associated with some morbidity, and therefore medical treatment should always be attempted first.

Sclerosing injections have been associated with complications such as neurogenic bladder. We have found linear cauterization effective and with few complications other than recurrence. In the operating room, the prolapse is recreated by traction on the mucosa. Linear burns are made through nearly the full thickness of the mucosa using electrocautery. One can usually make 8 linear burns on the outside and 4 on the inside of the prolapsed mucosa. In the immediate postoperative period, prolapse can still occur, but in the next several weeks, the burned areas contract and keep the mucosa within the anal canal. The Delorme mucosal sleeve resection addresses mucosal prolapse via a transanal approach by incising, prolapsing, and amputating the redundant mucosa. The resulting mucosal defect is then approximated with absorbable suture.

For patients with procidentia or full-thickness prolapse or intussusception of the rectosigmoid (usually from myelodysplasia or other sacral root lesions), other, more invasive options exist. Those most commonly in use by pediatric surgeons today include the following: A modification of the Thiersch procedure involves placing a subcutaneous suture to narrow the anal opening. Complications include obstruction, fecal impaction, and fistula formation. Laparoscopic rectopexy is effective and can be performed as an outpatient. The Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy is a transanal, full-thickness resection of redundant bowel with a primary anastomosis to the anus.

Bibliography

Flum AS, Golladay ES, Teitelbaum DH. Recurrent rectal prolapse following primary surgical treatment. Pediatr Surg Int . 2010;26:427–431.

Koivusalo AI, Pakarinen MP, Rintala RI, Seuri R. Dynamic defecography in the diagnosis of paediatric rectal prolapse and related disorders. Pediatr Surg Int . 2012;28:815–820.

Potter DD, Bruny JL, Allshouse MJ, et al. Laparoscopic suture rectopexy for full-thickness anorectal prolapse in children: an effective outpatient procedure. J Pediatr Surg . 2010;45:2103–2107.

Shah A, et al. Persistent rectal prolapse in children: sclerotherapy and surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int . 2005;21:270.

Pilonidal Sinus and Abscess

Christina M. Shanti

The etiology of pilonidal disease remains unknown; 3 hypotheses explaining its origin have been proposed. The first states that trauma, such as can occur with prolonged sitting, impacts hair into the subcutaneous tissue, which serves as a nidus for infection. The second suggests that in some patients, hair follicles exist in the subcutaneous tissues, perhaps the result of some embryologic abnormality, and that they serve as a focal point for infection, especially with secretion of hair oils. The third speculates that motion of the buttocks disturbs a particularly deep midline crease and works bacteria and hair beneath the skin. This theory arises from the apparent improved short-term and long-term results of operations that close the wound off the midline, obliterating the deep natal cleft.

Pilonidal disease usually manifests in adolescents or young adults with significant hair over the midline sacral and coccygeal areas. It can occur as an acute abscess with a tender, warm, flocculent, erythematous swelling or as draining sinus tracts. This disease does not resolve with nonoperative treatment. An acute abscess should be drained and packed open with appropriate anesthesia. Oral broad-spectrum antibiotics covering the usual isolates (S. aureus and Bacteroides species) are prescribed, and the patient's family withdraws the packing over the course of a week. When the packing has been totally removed, the area can be kept clean by a bath or shower. The wound usually heals completely in 6 wk. Once the wound is healed, most pediatric surgeons feel that elective excision should be scheduled to avoid recurrence. There are some reports, however, this is only necessary if the disease recurs. Usually, patients who present with sinus tracts are managed with a single elective excision.

Most surgeons carefully identify the extent of each sinus tract and excise all skin and subcutaneous tissue involved to the fascia covering the sacrum and coccyx. Some close the wound in the midline; others leave it open and packed for healing by secondary intention. This method has been modified by the application of a vacuum-assisted (VAC sponge) dressing. This is a system that applies continuous suction to a porous dressing. It is usually changed every 3 days and can be done at home with the assistance of a nurse. Some marsupialize the wound by suturing the skin edges down to the exposed fascia covering the sacrum and coccyx. There appears to be improved success with excision and closure in such a way that the suture line is not in the midline. Currently there appears to be enthusiasm for the less radical methods that Bascom has introduced, treating simple sinus tracts with small local procedures and limiting excision to only diseased tissues, while still keeping the incision off the midline. Recurrence or wound-healing problems are relatively common, occurring in 9–27% of cases. The variety of treatments and procedures currently being described indicates that all are associated with significant complications and delays in return to normal activity. Still, it is rare for problems to persist beyond 1-2 yr. Recalcitrant cases are treated by a large, full-thickness gluteal flap or skin grafting.

A simple dimple located in the midline intergluteal cleft, at the level of the coccyx, is seen relatively commonly in normal infants. No evidence indicates that this little sinus provokes any problems for the patient. An open dermal sinus is an asymptomatic, benign condition that does not require operative intervention.

Bibliography

Dudink R, Veldkamp J, Nienhuijs S, et al. Secondary healing versus midline closure and modified bascom natal cleft lift for pilonidal sinus disease. Scand J Surg . 2011;100:110–113.

Fike FB, Mortellaro VE, Juang D, et al. Experience with pilonidal disease in children. J Surg Res . 2011;170:165–168.

Hsieh MH, Perry V, Gupta N, et al. The effects of detethering on the urodynamics profile in children with a tethered cord. J Neurosurg . 2006;105:391–395.

Lee SL, Tejirian T, Abbas MA. Current management of adolescent pilonidal disease. J Pediatr Surg . 2008;43:1124–1127.

Nasr A, Ein SH. A pediatric surgeon's 35-year experience with pilonidal disease in a Canadian children's hospital. Can J Surg . 2011;54:39–42.