Viral Hepatitis

M. Kyle Jensen, William F. Balistreri

Viral hepatitis continues to be a major health problem in both developing and developed countries; there has been significant progress in efforts to recognize and to treat infected subjects. This disorder is caused by the 5 pathogenic hepatotropic viruses recognized to date: hepatitides A (HAV), B (HBV), C (HCV), D (HDV), and E (HEV) viruses (Table 385.1 ). Many other viruses (and diseases) can cause hepatitis, usually as a component of a multisystem disease. These include herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, HIV, rubella, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, parvovirus B19, and arboviruses (Table 385.2 ).

Table 385.1

Features of the Hepatotropic Viruses

| VIROLOGY | HAV RNA | HBV DNA | HCV RNA | HDV RNA | HEV RNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation (days) | 15-19 | 60-180 | 14-160 | 21-42 | 21-63 |

| Transmission | |||||

| Rare | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| No | Yes | Rare | Yes | No | |

| No | Yes | Uncommon (5–15%) | Yes | No | |

| Chronic infection | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Fulminant disease | Rare | Yes | Rare | Yes | Yes |

HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HEV, hepatitis E virus.

Table 385.2

Causes and Differential Diagnosis of Hepatitis in Children

| INFECTIOUS |

| NONVIRAL LIVER INFECTIONS |

| AUTOIMMUNE |

| METABOLIC |

| TOXIC |

| ANATOMIC |

| HEMODYNAMIC |

| NONALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE |

From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease , ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, WB Saunders.

The hepatotropic viruses are a heterogeneous group of infectious agents that cause similar acute clinical illness. In most pediatric patients, the acute phase causes no or mild clinical disease. Morbidity is related to rare cases of acute liver failure (ALF) in susceptible patients, or to the development of a chronic disease state and attendant complications that several of these viruses (hepatitides B, C, and D) commonly cause.

Issues Common to All Forms of Viral Hepatitis

Differential Diagnosis

Often what brings the patient with hepatitis to medical attention is clinical icterus, with yellow skin and/or mucous membranes. The liver is usually enlarged and tender to palpation and percussion. Splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy may be present. Extrahepatic symptoms (rashes, arthritis) are more commonly seen in HBV and HCV infections. Clinical signs of bleeding, altered sensorium, or hyperreflexia should be carefully sought, because they mark the onset of encephalopathy and ALF.

The differential diagnosis varies with age of presentation. In the newborn period, infection is a common cause of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia; the infectious cause is either a bacterial agent (e.g., Escherichia coli , Listeria, syphilis) or a nonhepatotropic virus (e.g., enteroviruses, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus, which may also cause a nonicteric severe hepatitis). Metabolic diseases (α1 -antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, tyrosinemia), anatomic causes (biliary atresia, choledochal cysts), and inherited forms of intrahepatic cholestasis should always be excluded.

In later childhood, extrahepatic obstruction (gallstones, primary sclerosing cholangitis, pancreatic pathology), inflammatory conditions (autoimmune hepatitis, juvenile inflammatory arthritis, Kawasaki disease), immune dysregulation (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis), infiltrative disorders (malignancies), toxins and medications, metabolic disorders (Wilson disease, cystic fibrosis), and infection (Epstein-Barr virus, varicella, malaria, leptospirosis, syphilis) should be ruled out.

Pathogenesis

The acute response of the liver to hepatotropic viruses involves a direct cytopathic and/or an immune-mediated injury. The entire liver is involved. Necrosis is usually most marked in the centrilobular areas. An acute mixed inflammatory infiltrate predominates in the portal areas but also affects the lobules. The lobular architecture remains intact, although balloon degeneration and necrosis of single or groups of parenchymal cells commonly occur. Fatty change is rare except with HCV infection. Bile duct proliferation, but not bile duct damage, is common. Diffuse Kupffer cell hyperplasia is noticeable in the sinusoids. Neonates often respond to hepatic injury by forming giant cells . In fulminant hepatitis, parenchymal collapse occurs on the described background. With recovery, the liver morphology returns to normal within 3 mo of the acute infection. If chronic hepatitis develops, the inflammatory infiltrate settles in the periportal areas and often leads to progressive scarring. Both of these hallmarks of chronic hepatitis are seen in cases of HBV and HCV.

Common Biochemical Profiles in the Acute Infectious Phase

Acute liver injury caused by these viruses manifests in 3 main functional liver biochemical profiles. These serve as an important guide to diagnosis, supportive care, and monitoring in the acute phase of the infection for all viruses. As a reflection of cytopathic injury to the hepatocytes, there is a rise in serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The magnitude of enzyme elevation does not correlate with the extent of hepatocellular necrosis and has little prognostic value. There is usually slow improvement over several weeks, but AST and ALT levels lag the serum bilirubin level, which tends to normalize first. Rapidly falling aminotransferase levels can predict a poor outcome, particularly if their decline occurs in conjunction with a rising bilirubin level and a prolonged prothrombin time (PT); this combination of findings usually indicates that massive hepatic injury has occurred.

Cholestasis , defined by elevated serum conjugated bilirubin levels, results from abnormal bile flow at the canalicular and cellular level because of hepatocyte damage and inflammatory mediators. Elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase, 5′-nucleotidase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase levels, mark cholestasis. Absence of cholestatic markers does not rule out progression to chronicity in HCV or HBV infections.

Altered synthetic function is the most important marker of liver injury. Synthetic dysfunction is reflected by a combination of abnormal protein synthesis (prolonged PT, high international normalized ratio [INR], low serum albumin levels), metabolic disturbances (hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hyperammonemia), poor clearance of medications dependent on liver function, and altered sensorium with increased deep tendon reflexes (hepatic encephalopathy). Monitoring of synthetic function should be the main focus in clinical follow-up to define the severity of the disease. In the acute phase, the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction guides treatment and helps to establish intervention criteria. Abnormal liver synthetic function is a marker of liver failure and is an indication for prompt referral to a transplant center. Serial assessment is necessary because liver dysfunction does not progress linearly.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is the most prevalent form; this virus is also responsible for most forms of acute and benign hepatitis. Although fulminant hepatic failure due to HAV can occur, it is rare (<1% of cases in the United States) and occurs more often in adults than in children and in hyperendemic communities.

Etiology

HAV is an RNA virus, a member of the picornavirus family. It is heat stable and has limited host range—namely, the human and other primates.

Epidemiology

HAV infection occurs throughout the world but is most prevalent in developing countries. In the United States, 30–40% of the adult population has evidence of previous HAV infection. Hepatitis A is thought to account for approximately 50% of all clinically apparent acute viral hepatitis in the United States. As a result of aggressive implementation of childhood vaccination programs, the prevalence of symptomatic HAV cases worldwide has declined significantly. However, outbreaks in developing countries and in daycare centers (where the spread of HAV from young, nonicteric, infected children can occur easily) as well as multiple foodborne and waterborne outbreaks have justified the implementation of intensified universal vaccination programs.

HAV is highly contagious. Transmission is almost always by person-to-person contact through the fecal–oral route. Perinatal transmission occurs rarely. No other form of transmission is recognized. HAV infection during pregnancy or at the time of delivery does not appear to result in increased complications of pregnancy or clinical disease in the newborn. In the United States, increased risk of infection is found in contacts with infected persons, childcare centers, and household contacts. Infection is also associated with contact with contaminated food or water and after travel to endemic areas. Common source foodborne and waterborne outbreaks continue to occur, including several caused by contaminated shellfish, frozen berries, and raw vegetables; no known source is found in about half of the cases.

The mean incubation period for HAV is approximately 3 wk. Fecal excretion of the virus starts late in the incubation period, reaches its peak just before the onset of symptoms, and resolves by 2 wk after the onset of jaundice in older subjects. The duration of fecal viral excretion is prolonged in infants. The patient is, therefore, contagious before clinical symptoms are apparent and remains so until viral shedding ceases.

Clinical Manifestations

HAV is responsible for acute hepatitis only. Often, this is an anicteric illness, with clinical symptoms indistinguishable from other forms of viral gastroenteritis, particularly in young children.

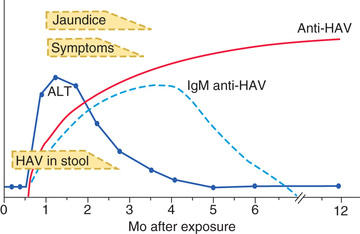

The illness is more likely to be symptomatic in older adolescents or adults, in patients with underlying liver disorders, and in those who are immunocompromised. It is characteristically an acute febrile illness with an abrupt onset of anorexia, nausea, malaise, vomiting, and jaundice. The typical duration of illness is 7-14 days (Fig. 385.1 ).

Other organ systems can be affected during acute HAV infection. Regional lymph nodes and the spleen may be enlarged. The bone marrow may be moderately hypoplastic, and aplastic anemia has been reported. Tissue in the small intestine might show changes in villous structure, and ulceration of the gastrointestinal tract can occur, especially in fatal cases. Acute pancreatitis and myocarditis have been reported, though rarely, and nephritis, arthritis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemia can result from circulating immune complexes.

Diagnosis

Acute HAV infection is diagnosed by detecting antibodies to HAV, specifically, anti-HAV (immunoglobulin [Ig] M) by radioimmunoassay or, rarely, by identifying viral particles in stool. A viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is available for research use (Table 385.3 ). Anti-HAV is detectable when the symptoms are clinically apparent, and it remains positive for 4-6 mo after the acute infection. A neutralizing anti-HAV (IgG) is usually detected within 8 wk of symptom onset and is measured as part of a total anti-HAV in the serum. Anti-HAV (IgG) confers long-term protection. Rises in serum levels of ALT, AST, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, 5′-nucleotidase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase are almost universally found and do not help to differentiate the cause of hepatitis.

Table 385.3

Diagnostic Blood Tests: Serology and Viral Polymerase Chain Reaction

| HAV | HBV | HCV | HDV | HEV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACUTE/ACTIVE INFECTION | ||||

| Anti-HAV IgM (+) | Anti-HBc IgM (+) | Anti-HCV (+) | Anti-HDV IgM (+) | Anti-HEV IgM (+) |

| Blood PCR positive* |

HBsAg (+) Anti-HBs (−) HBV DNA (+) (PCR) |

HCV RNA (+) (PCR) |

Blood PCR positive HBsAg (+) Anti-HBs (−) |

Blood PCR positive* |

| PAST INFECTION (RECOVERED) | ||||

| Anti-HAV IgG(+) |

Anti-HBs (+) Anti-HBc IgG (+) † |

Anti-HCV (+) Blood PCR (−) |

Anti-HDV IgG (+) Blood PCR (−) |

Anti-HEV IgG (+) Blood PCR (−) |

| CHRONIC INFECTION | ||||

| N/A |

Anti-HBc IgG (+) HBsAg (+) Anti-HBs (−) PCR (+) or (−) |

Anti-HCV (+) Blood PCR (+) |

Anti-HDV IgG (+) Blood PCR (−) HBsAg (+) Anti-HBs (−) |

N/A |

| VACCINE RESPONSE | ||||

| Anti-HAV IgG (+) |

Anti-HBs (+) Anti-HBc (−) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

* Research tool.

† Still poses a risk for reactivation.

HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBs, hepatitis B surface; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; Ig, immunoglobulin; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Complications

Although most patients achieve full recovery, distinct complications can occur. ALF from HAV infection is an infrequent complication of HAV. Those at risk for this complication are adolescents and adults, but also immunocompromised patients or those with underlying liver disorders. The height of HAV viremia may be linked to the severity of hepatitis. In the United States, HAV represents <0.5% of pediatric-age ALF; HAV is responsible for up to 3% mortality in the adult population with ALF. In endemic areas of the world, HAV constitutes up to 40% of all cases of pediatric ALF. HAV can also progress to a prolonged cholestatic syndrome that waxes and wanes over several months. Pruritus and fat malabsorption are problematic and require symptomatic support with antipruritic medications and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation. This syndrome occurs in the absence of any liver synthetic dysfunction and resolves without sequelae.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for hepatitis A. Supportive treatment consists of intravenous hydration as needed, and antipruritic agents and fat-soluble vitamins for the prolonged cholestatic form of disease. Serial monitoring for signs of ALF is prudent and, if ALF is diagnosed, a prompt referral to a transplantation center can be lifesaving.

Prevention

Patients infected with HAV are contagious for 2 wk before and approximately 7 days after the onset of jaundice and should be excluded from school, childcare, or work during this period. Careful hand-washing is necessary, particularly after changing diapers and before preparing or serving food. In hospital settings, contact and standard precautions are recommended for 1 wk after onset of symptoms.

Immunoglobulin

Indications for intramuscular administration of Ig include preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis (Table 385.4 ). Ig is recommended for preexposure prophylaxis for susceptible travelers to countries where HAV is endemic, and it provides effective protection for up to 2 mo. HAV vaccine given any time before travel is preferred for preexposure prophylaxis in healthy persons, but Ig ensures an appropriate prophylaxis in children younger than 12 mo old, patients allergic to a vaccine component, or those who elect not to receive the vaccine. If travel is planned in <2 wk, older patients, immunocompromised hosts, and those with chronic liver disease or other medical conditions should receive both Ig and the HAV vaccine.

Table 385.4

Indications and Updated Dosage Recommendations for GamaSTAN S/D Human Immune Globulin for Preexposure and Postexposure Prophylaxis Against Hepatitis A Infection

| INDICATION | UPDATED DOSAGE RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| Preexposure prophylaxis | |

| Up to 1 mo of travel | 0.1 mL/kg |

| Up to 2 mo of travel | 0.2 mL/kg |

| 2 mo of travel or longer | 0.2 mL/kg (repeat every 2 mo) |

| Postexposure prophylaxis | 0.1 mL/kg |

From Nelson NP: Updated dosing instruction for immune globulin (human) gamaSTAN S/D for hepatitis A virus prophylaxis, MMWR 66(36):959–960, 2017, Table, p. 959.

Ig prophylaxis in postexposure situations should be used as soon as possible (it is not effective if administered more than 2 wk after exposure). It is exclusively used for children younger than 12 mo old, immunocompromised hosts, those with chronic liver disease or in whom vaccine is contraindicated. Ig is preferred in patients older than 40 yr of age, with HAV vaccine preferred in healthy persons 12 mo to 40 yr old. An alternative approach is to immunize previously unvaccinated patients who are 12 mo old or older with the age-appropriate vaccine dosage as soon as possible. Ig is not routinely recommended for sporadic nonhousehold exposure (e.g., protection of hospital personnel or schoolmates). The vaccine has several advantages over Ig, including long-term protection, availability, and ease of administration, with cost similar to, or less than, that of Ig.

Vaccine

The availability of 2 inactivated, highly immunogenic, and safe HAV vaccines has had a major impact on the prevention of HAV infection. Both vaccines are approved for children older than 12 mo. They are administered intramuscularly in a 2-dose schedule, with the second dose given 6-12 mo after the first dose. Seroconversion rates in children exceed 90% after an initial dose and approach 100% after the second dose; protective antibody titer persists for longer than 10 yr in most patients. The immune response in immunocompromised persons, older patients, and those with chronic illnesses may be suboptimal; in those patients, combining the vaccine with Ig for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis is indicated. HAV vaccine may be administered simultaneously with other vaccines. A combination HAV and HBV vaccine is approved in adults older than age 18 yr. For healthy persons at least 12 mo old, vaccine is preferable to Ig for preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis (see Table 385.3 ).

In the United States and some other countries, universal vaccination is now recommended for all children older than 12 mo. Nevertheless, studies show <50% of U.S. adolescents have received even a single dose of the vaccine, and <30% have received the complete vaccine series. The vaccine is effective in curbing outbreaks of HAV because of rapid seroconversion and the long incubation period of the disease.

Prognosis

The prognosis for the patient with HAV is excellent, with no long-term sequelae. The only feared complication is ALF. Nevertheless, HAV infection remains a major cause of morbidity; it has a high socioeconomic impact during epidemics and in endemic areas.

Hepatitis B

Etiology

HBV, a member of the Hepadnaviridae family, has a circular, partially double-stranded DNA genome composed of approximately 3,200 nucleotides. Four constitutive genes have been identified: the S (surface), C (core), X, and P (polymer) genes. The surface of the virus includes particles, designated as the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), which consist of 22 nm diameter spherical particles and 22 nm wide tubular particles with a variable length of up to 200 nm. The inner portion of the virion contains the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), the nucleocapsid that encodes the viral DNA, and a nonstructural antigen called the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), a nonparticulate soluble antigen derived from HBcAg by proteolytic self-cleavage. HBeAg serves as a marker of active viral replication and usually correlates with the HBV DNA levels. Replication of HBV occurs predominantly in the liver but also occurs in the lymphocytes, spleen, kidney, and pancreas.

Epidemiology

HBV has been detected worldwide, with an estimated 400 million persons chronically infected. The areas of highest prevalence of HBV infection are sub-Saharan Africa, China, parts of the Middle East, the Amazon basin, and the Pacific Islands. In the United States, the native population in Alaska had the highest prevalence rate before the implementation of their universal vaccination programs. An estimated 1.25 million persons in the United States are chronic HBV carriers, with approximately 300,000 new cases of HBV occurring each year, the highest incidence being among adults 20-39 yr of age. One in 4 chronic HBV carriers will develop serious sequelae in their lifetime. The number of new cases in children reported each year is thought to be low but is difficult to estimate because many infections in children are asymptomatic. In the United States, since 1982 when the first vaccine for HBV was introduced, the overall incidence of HBV infection has been reduced by more than half. Since the implementation of universal vaccination programs in Taiwan and the United States, substantial progress has been made toward eliminating HBV infection in children in these countries. In fact, in Alaska, where HBV neared epidemic proportions, universal newborn vaccination with mass screening and immunization of susceptible Alaska Natives virtually eliminated symptomatic HBV and secondary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

HBV is present in high concentrations in blood, serum, and serous exudates and in moderate concentrations in saliva, vaginal fluid, and semen. Efficient transmission occurs through blood exposure and sexual contact. Risk factors for HBV infection in children and adolescents include acquisition by intravenous drugs or blood products, contaminated needles used for acupuncture or tattoos, sexual contact, institutional care, and intimate contact with carriers. No risk factors are identified in approximately 40% of cases. HBV is not thought to be transmitted via indirect exposure, such as sharing toys. After infection, the incubation period ranges from 45-160 days, with a mean of approximately 120 days. In children, the most important risk factor for acquisition of HBV remains perinatal exposure to an HBsAg-positive mother. The risk of transmission is greatest if the mother is HBeAg-positive; up to 90% of these infants become chronically infected if untreated. Additional risk factors include high maternal HBV viral load (HBeAg/HBV DNA titers) and delivery of a prior infant who developed HBV despite appropriate prophylaxis. In most perinatal cases, serologic markers of infection and antigenemia appear 1-3 mo after birth, suggesting that transmission occurred at the time of delivery. Virus contained in amniotic fluid or in maternal feces or blood may be the source. Immunoprophylaxis with hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and the HBV immunization, given within 12 hr of delivery, is highly effective in preventing infection and protects >95% of neonates born to HBsAg-positive mothers. Of the 22,000 infants born each year to HBsAg-positive mothers in the United States, >98% receive immunoprophylaxis and are thus protected. Infants who fail to receive the complete vaccination series (e.g., homeless children, international adoptees, and children born outside the United States) have the highest incidence of developing chronic HBV. These and all infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers should have follow-up HBsAg and anti-HBs tested to determine appropriate follow-up. The mothers (HBeAg positive) of these infants who develop chronic HBV infection should receive antiviral therapy during the third trimester for subsequent pregnancies.

HBsAg is inconsistently recovered in human milk of infected mothers. Breastfeeding of nonimmunized infants by infected mothers does not seem to confer a greater risk of hepatitis than does formula feeding.

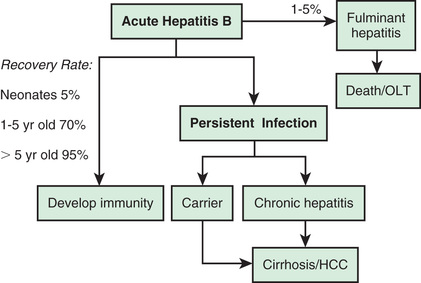

The risk of developing chronic HBV infection, defined as being positive for HBsAg for longer than 6 mo, is inversely related to age of acquisition. In the United States, although <10% of infections occur in children, these infections account for 20–30% of all chronic cases. This risk of chronic infection is 90% in children younger than 1 yr; the risk is 30% for those 1-5 yr of age and 2% for adults. Chronic HBV infection is associated with the development of chronic liver disease and HCC. The carcinoma risk is independent of the presence of cirrhosis and was the most prevalent cancer-related death in young adults in Asia where HBV was endemic.

HBV has 10 genotypes (A-J). A is pandemic, B and C are prevalent in Asia, D is seen in Southern Europe, E in Africa, F in the United States, G in the United States and France, H in Central America, I in southeast Asia, and J in Japan. Genetic variants have become resistant to some antiviral agents.

Pathogenesis

The acute response of the liver to HBV is similar to that of other viruses. Persistence of histologic changes in patients with hepatitis B indicates development of chronic liver disease. HBV, unlike the other hepatotropic viruses, is a predominantly noncytopathogenic virus that causes injury mostly by immune-mediated processes. The severity of hepatocyte injury reflects the degree of the immune response, with the most complete immune response being associated with the greatest likelihood of viral clearance but also the most severe injury to hepatocytes. The first step in the process of acute hepatitis is infection of hepatocytes by HBV, resulting in expression of viral antigens on the cell surface. The most important of these viral antigens may be the nucleocapsid antigens—HBcAg and HBeAg. These antigens, in combination with class I major histocompatibility proteins, make the cell a target for cytotoxic T-cell lysis.

The mechanism for development of chronic hepatitis B is less well understood. To permit hepatocytes to continue to be infected, the core protein or major histocompatibility class I protein might not be recognized, the cytotoxic lymphocytes might not be activated, or some other, yet unknown mechanism might interfere with destruction of hepatocytes. This tolerance phenomenon predominates in the perinatally acquired cases, resulting in a high incidence of persistent HBV infection in children with no or little inflammation in the liver, normal liver enzymes, and markedly elevated HBV viral load. Although end-stage liver disease rarely develops in those patients, the inherent HCC risk is high, possibly related, in part, to uncontrolled viral replication cycles.

ALF has been seen in infants of chronic carrier mothers who have anti-HBe or are infected with a precore-mutant strain. This fact led to the postulate that HBeAg exposure in utero in infants of chronic carriers likely induces tolerance to the virus once infection occurs postnatally. In the absence of this tolerance, the liver is massively attacked by T cells and the patient presents with ALF.

Immune-mediated mechanisms are also involved in the extrahepatic conditions that can be associated with HBV infections. Circulating immune complexes containing HBsAg can result in polyarteritis nodosa, membranous or membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Clinical Manifestations

Many acute cases of HBV infection in children are asymptomatic, as evidenced by the high carriage rate of serum markers in persons who have no history of acute hepatitis (Table 385.5 ). The usual acute symptomatic episode is similar to that of HAV and HCV infections but may be more severe and is more likely to include involvement of skin and joints (Fig. 385.2 ).

Table 385.5

Typical Interpretation of Test Results for Hepatitis B Virus Infection

| HBsAg | TOTAL ANTI-HBc | IgM ANTI-HBc | ANTI-HBs | HBV DNA | INTERPRETATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | − | − | − | − | Never infected |

| + | − | − | − | + or − | Early acute infection; transient (up to 18 days) after vaccination |

| + | + | + | − | + | Acute infection |

| − | + | + | + or − | + or − | Acute resolving infection |

| − | + | − | + | − | Recovered from past infection and immune |

| + | + | − | − | + | Chronic infection |

| − | + | − | − | + or − | False-positive (i.e., susceptible); past infection; “low-level” chronic infection; or passive transfer of anti-HBc to infant born to HBsAg-positive mother |

| − | − | − | + | − | Immune if anti-HBs concentration is ≥10 mIU/mL after vaccine series completion; passive transfer after hepatitis B immune globulin administration |

−, negative; +, positive; anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid; IgM, immunoglobulin class M.

From Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al: Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, MMWR 67(1):1–29, 2018, Table 1, p. 7.

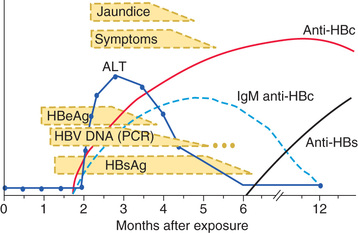

The first biochemical evidence of HBV infection is elevation of serum ALT levels, which begin to rise just before development of fatigue, anorexia, and malaise, at approximately 6-7 wk after exposure. The illness is preceded, in a few children, by a serum sickness–like prodrome marked by arthralgia or skin lesions, including urticarial, purpuric, macular, or maculopapular rashes. Papular acrodermatitis, the Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, can also occur. Other extrahepatic conditions associated with HBV infections in children include polyarteritis nodosa, glomerulonephritis, and aplastic anemia. Jaundice is present in approximately 25% of acutely infected patients and usually begins approximately 8 wk after exposure and lasts approximately 4 wk.

In the usual course of resolving HBV infection, symptoms persist for 6-8 wk. The percentage of children in whom clinical evidence of hepatitis develops is higher for HBV than for HAV, and the rate of ALF is also greater. Most patients do recover, but the chronic carrier state complicates up to 10% of cases acquired in adulthood. The rate of development of chronic infection depends largely on the mode and age of acquisition and occurs in up to 90% of perinatally-infected cases. Cirrhosis and HCC are only seen with chronic infection. Chronic HBV infection has 3 identified phases: immune tolerant, immune active, and inactive. Most children fall in the immune-tolerant phase, against which no effective therapy has been developed. Most treatments target the immune active phase of the disease, characterized by active inflammation, elevated ALT/AST levels, and progressive fibrosis. Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion, defined as the development of anti-HBe and loss of HBeAg, occurs in the immune-tolerant phase, albeit at low rates of 4–5% per year. It is more common in childhood-acquired HBV rather than in perinatally transmitted infections. Seroconversion can occur over many years, during which time significant damage to the liver may take place. There are no large studies that accurately assess the lifetime risks and morbidities of children with chronic HBV infection, making decisions regarding the rationale, efficacy, and timing of still less-than-ideal treatments difficult. Reactivation of chronic infection has been reported in immunosuppressed children treated with chemotherapy, biologic immunomodulators such as infliximab, or T-cell depleting agents, leading to an increased risk of ALF or to rapidly progressing fibrotic liver disease (Table 385.6 ).

Table 385.6

Causes of Hepatitis Flares in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B

| CAUSE OF FLARE | COMMENT |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous | Factors that precipitate viral replication are unclear |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | Flares are often observed during withdrawal of the agent; preemptive antiviral therapy is required |

| Antiviral therapy for HBV | |

| Interferon | Flares are often observed during the second to third month of therapy in 30% of patients; may herald virologic response |

| Nucleoside analog | |

| During treatment | Flares are no more common than with placebo |

| Drug-resistant HBV | Severe consequences can occur in patients with advanced liver disease |

| On withdrawal | Flares are caused by the rapid re-emergence of wild-type HBV; severe consequences can occur in patients with advanced liver disease |

| HIV treatment | Flares can occur as a result of the direct toxicity of HAART or with immune reconstitution; HBV increases the risk of antiretroviral drug hepatotoxicity |

| Genotypic variation | |

| Precore and core promoter mutants | Fluctuations in serum alanine aminotransferase levels are common with precore mutants |

| Superinfection with other hepatitis viruses | May be associated with suppression of HBV replication |

HAART, Highly active antiretroviral therapy; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

From Wells JT, Perillo R: Hepatitis B. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors: Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease , 10/e, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Table 79.1.

Diagnosis

The serologic profile of HBV infection is more complex than for HAV infection and differs depending on whether the disease is acute or chronic (Fig. 385.3 , see Table 385.5 ). Several antigens and antibodies are used to confirm the diagnosis of acute HBV infection (see Table 385.3 ). Routine screening for HBV infection requires assay of multiple serologic markers (HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBs). HBsAg is an early serologic marker of infection and is found in almost all infected persons; its rise closely coincides with the onset of symptoms. Persistence of HBsAg beyond 6 mo defines the chronic infection state. During recovery from acute infection, because HBsAg levels fall before symptoms wane, IgM antibody to HBcAg (anti-HBc IgM) might be the only marker of acute infection. Anti-HBc IgM rises early after the infection and remains positive for many months before being replaced by anti-HBc IgG, which then persists for years. Anti-HBs marks serologic recovery and protection. Only anti-HBs is present in persons immunized with hepatitis B vaccine, whereas both anti-HBs and anti-HBc are detected in persons with resolved infection. HBeAg is present in active acute or chronic infection and is a marker of infectivity. The development of anti-HBe, termed seroconversion, marks improvement and is a goal of therapy in chronically infected patients. HBV DNA can be detected in the serum of acutely infected patients and chronic carriers. High DNA titers are seen in patients with HBeAg, and they typically fall once anti-HBe develops.

Complications

ALF with coagulopathy, encephalopathy, and cerebral edema occurs more commonly with HBV than the other hepatotropic viruses. The risk of ALF is further increased when there is coinfection or superinfection with HDV or in an immunosuppressed host. Mortality from ALF is >30%, and liver transplantation is the only effective intervention. Supportive care aimed at sustaining patients and early referral to a liver transplantation center can be lifesaving. As mentioned, HBV infection can also result in chronic hepatitis, which can lead to cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease complications, and HCC. Membranous glomerulonephritis with deposition of complement and HBeAg in glomerular capillaries is a rare complication of HBV infection.

Treatment

Treatment of acute HBV infection is largely supportive. Close monitoring for liver failure and extrahepatic morbidities is key. Treatment of chronic HBV infection is in evolution; no 1 drug currently achieves consistent, complete eradication of the virus. The natural history of chronic HBV infection in children is complex, and there is a lack of reliable long-term outcome data on which to base treatment recommendations. Treatment of chronic HBV infection in children should be individualized and done under the care of a pediatric hepatologist experienced in treating the disease.

The goal of treatment is to reduce viral replication defined by having undetectable HBV DNA in the serum and development of anti-HBe, termed seroconversion. The development of anti-HBe transforms the disease into an inactive form, thereby decreasing infectivity, active liver injury and inflammation, fibrosis progression, and the risk of HCC. Treatment is only indicated for patients in the immune-active form of the disease, as evidenced by elevated ALT and/or AST, who have fibrosis on liver biopsy, putting the child at higher risk for cirrhosis during childhood.

Treatment Strategies

Interferon-α2b (IFN-α2b) has immunomodulatory and antiviral effects (Table 385.7 ). It has been used in children, with long-term viral response rates similar to the 25% rate reported in adults. Interferon (IFN) use is limited by its subcutaneous administration, treatment duration of 24 wk, and side effects (flu-like symptoms, marrow suppression, depression, retinal changes, autoimmune disorders). IFN is further contraindicated in decompensated cirrhosis. One advantage of IFN, compared to other treatments, is that viral resistance does not develop with its use.

Table 385.7

Positive and Negative Factors to Consider in the Decision to Treat Hepatitis B With Peginterferon or a Nucleoside or Nucleotide Analog

| AGENT | POSITIVE FACTORS | NEGATIVE FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Peginterferon | Finite duration of treatment | Inconvenience of subcutaneous injection |

| Durable off-treatment response | Frequent side effects | |

|

More rapid disappearance of HBsAg Immunostimulatory as well as intrinsically antiviral |

Clearance of HBsAg in a small minority of patients depending on genotype | |

| Potential risk of ALT flares in patients with advanced liver fibrosis | ||

| Better tolerability compared with its use in hepatitis C | Relative contraindication in patients older than age 60 or those with comorbid illnesses | |

| Nucleoside or nucleotide analog | Negligible side effects | Slight risk of nephropathy with nucleotide analogs (adefovir, tenofovir) |

| Convenience; ready acceptance by patients | Drug expense can be considerable during long-term use | |

|

Potent inhibition of virus replication Reduced drug resistance with the third-generation nucleoside analogs |

Long or indefinite treatment needed for both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients | |

| Access issues in developing nations |

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

From Wells JT, Perillo R: Hepatitis B. In Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors: Sleisenger and Fordtran's gastrointestinal and liver disease , 10/e, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Table 79.4.

Lamivudine is an oral synthetic nucleoside analog that inhibits the viral enzyme reverse transcriptase. In children older than 2 yr of age, its use for 52 wk resulted in HBeAg clearance in 34% of patients with an ALT >2 times normal; 88% remained in remission at 1 yr. It has a good safety profile. Lamivudine has to be used for ≥ 6 mo after viral clearance, and the emergence of a mutant viral strain (YMDD) poses a barrier to its long-term use. Combination therapy in children using IFN and lamivudine did not seem to improve the rates of response in most series.

Adefovir (a purine analog that inhibits viral replication) is approved for use in children older than 12 yr of age, in whom a prospective 1-yr study showed 23% seroconversion. No viral resistance was noted in that study but has been reported in adults.

Entecavir (a nucleoside analog that inhibits replication) is currently approved for use in children older than 2 yr of age. Prospective data has shown a 21% seroconversion rate in adults with minimal resistance developing. Patients in whom resistance to lamivudine developed have an increased risk of resistance developing to entecavir.

Tenofovir (a nucleotide analog that inhibits viral replication) is also approved for use in children older than 12 yr of age. Prospective data have shown a 21% seroconversion rate with a very low rate of resistance developing. Patients with lamivudine-resistant mutations do not appear to have an increased rate of resistance. Concern exists over long-term use and bone mineral density.

Peginterferon-α2 has the same mechanism of action as IFN but is given once weekly. This formulation has not been approved in the United States but is recommended for the treatment of chronic HBV in other countries. Patients most likely to respond to currently available drugs have low serum HBV DNA titers, are HBeAg-positive, have active hepatic inflammation (ALT greater than twice the upper limit of normal for at least 6 mo), and recently acquired disease.

Immune tolerant patients—those with normal ALT and AST, who are HBeAg-positive with elevated viral load—are currently not considered for treatment, although the emergence of new treatment paradigms is promising for this large, yet hard-to-treat, subgroup of patients.

Prevention

The most effective prevention strategies have resulted from the screening of pregnant mothers and the use of HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine in infants (Tables 385.8 to 385.11 ). In HBsAg-positive and HBeAg-positive mothers, a 10% risk of chronic HBV infection exists compared to 1% in HBeAg-negative mothers. This knowledge offers screening strategies that may affect both mother and infant by using antiviral medications during the third trimester. Guidelines suggest that mothers with an HBV DNA viral load >200,000 IU/mL receive an antiviral such as telbivudine, lamivudine, or tenofovir during the third trimester, especially if they had a previous child who developed chronic HBV after receiving HBIG and the hepatitis B vaccine. This practice has proven safe with normal growth and development in infants of treated mothers.

Table 385.8

Strategy to Eliminate Hepatitis B Virus Transmission in the United States*

| HBV DNA testing for HBsAg-positive pregnant women, with suggestion of maternal antiviral therapy to reduce perinatal transmission when HBV DNA is >200,000 IU/mL |

| Prophylaxis (HepB vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin) for infants born to HBsAg-positive † women |

* Sources: Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, et al: A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents, MMWR Recomm Rep 54(No. RR-16):1–31, 2005; Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, et al: A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Part II: immunization of adults, MMWR Recomm Rep 55(No. RR-16):1–33, 2006.

† Refer to Table 385.9 for prophylaxis recommendations for infants born to women with unknown HBsAg status.

‡ Within 24 hr of birth for medically stable infants weighing ≥2,000 g.

§ Refer to Table 385.9 for birth dose recommendations for infants weighing <2,000 g.

HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

From Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al: Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, MMWR 67[1]:1–29, 2018, Box 2, p. 5.

Table 385.9

Hepatitis B Vaccine Schedules for Infants, by Infant Birthweight and Maternal Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Status

| BIRTHWEIGHT | MATERNAL HBsAg STATUS | SINGLE-ANTIGEN VACCINE | SINGLE-ANTIGEN + COMBINATION VACCINE † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOSE | AGE | DOSE | AGE | ||

| ≥2,000 g | Positive | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) |

| HBIG ‡ | Birth (≤12 hr) | HBIG | Birth (≤12 hr) | ||

| 2 | 1-2 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 6 mo § | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | ||||

| Unknown* | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | |

| 2 | 1-2 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 6 mo § | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | ||||

| Negative | 1 | Birth (≤24 hr) | 1 | Birth (≤24 hr) | |

| 2 | 1-2 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 6-18 mo § | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | ||||

| <2,000 g | Positive | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) |

| HBIG | Birth (≤12 hr) | HBIG | Birth (≤12 hr) | ||

| 2 | 1 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 2-3 mo | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | 4 | 6 mo § | ||

| Unknown | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | 1 | Birth (≤12 hr) | |

| HBIG | Birth (≤12 hr) | HBIG | Birth (≤12 hr) | ||

| 2 | 1 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 2-3 mo | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | 4 | 6 mo § | ||

| Negative | 1 | Hospital discharge or age 1 mo | 1 | Hospital discharge or age 1 mo | |

| 2 | 2 mo | 2 | 2 mo | ||

| 3 | 6-18 mo § | 3 | 4 mo | ||

| 4 | 6 mo § | ||||

* Mothers should have blood drawn and tested for HBsAg as soon as possible after admission for delivery; if the mother is found to be HBsAg positive, the infant should receive HBIG as soon as possible but no later than age 7 days.

† Pediarix should not be administered before age 6 wk.

‡ HBIG should be administered at a separate anatomical site from vaccine.

§ The final dose in the vaccine series should not be administered before age 24 wk (164 days).

HBIG, hepatitis B immune globulin; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

From Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al: Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, MMWR 67(1):1–29, 2018, Table 3, p. 12.

Table 385.10

Recommended Doses of Hepatitis B Vaccine by Group and Vaccine Type

| SINGLE-ANTIGEN VACCINE | COMBINATION VACCINE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECOMBIVAX | ENGERIX | PEDIARIX * | TWINRIX † | |||||

| Age Group (yr) | Dose (µg) | Vol (mL) | Dose (µg) | Vol (mL) | Dose (µg) | Vol (mL) | Dose (µg) | Vol (mL) |

| Birth-10 | 5 | 0.5 | 10 | 0.5 | 10* | 0.5 | N/A | N/A |

| 11-15 | 10 ‡ | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 11-19 | 5 | 0.5 | 10 | 0.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ≥20 | 10 | 1 | 20 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 20 † | 1 |

| HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS AND OTHER IMMUNE-COMPROMISED PERSONS | ||||||||

| <20 | 5 | 0.5 | 10 | 0.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ≥20 | 40 | 1 | 40 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

* Pediarix is approved for use in persons aged 6 wk through 6 yr (prior to the 7th birthday).

† Twinrix is approved for use in persons aged ≥18 yr.

‡ Adult formulation administered on a 2-dose schedule.

N/A, not applicable.

From Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al: Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, MMWR 67(1):1–29, 2018, Table 2, p. 10.

Table 385.11

Hepatitis B Vaccine Schedules for Children, Adolescents, and Adults

| AGE GROUP | SCHEDULE* (INTERVAL REPRESENTS TIME IN MONTHS FROM FIRST DOSE) |

|---|---|

| Children (l-10 yr) | |

| Adolescents (11-19 yr) | |

| Adults (≥20 yr) |

* Refer to package inserts for further information. For all ages, when the HepB vaccine schedule is interrupted, the vaccine series does not need to be restarted. If the series is interrupted after the 1st dose, the 2nd dose should be administered as soon as possible, and the 2nd and 3rd doses should be separated by an interval of at least 8 wk. If only the 3rd dose has been delayed, it should be administered as soon as possible. The final dose of vaccine must be administered at least 8 wk after the 2nd dose and should follow the 1st dose by at least 16 wk; the minimum interval between the 1st and 2nd doses is 4 wk. Inadequate doses of hepatitis B vaccine or doses received after a shorter-than-recommended dosing interval should be readministered, using the correct dosage or schedule. Vaccine doses administered ≤ 4 days before the minimum interval or age are considered valid. Because of the unique accelerated schedule for Twinrix, the 4-day guideline does not apply to the 1st 3 doses of this vaccine when administered on a 0-day, 7-day, 21-30-day, and 12-mo schedule (new recommendation).

† A 2-dose schedule of Recombivax adult formulation (10 µg) is licensed for adolescents aged 11-15 yr. When scheduled to receive the second dose, adolescents aged >15 yr should be switched to a 3-dose series, with doses 2 and 3 consisting of the pediatric formulation administered on an appropriate schedule.

‡ Twinrix is approved for use in persons aged ≥ 18 yr and is available on an accelerated schedule with doses administered at 0, 7, 21-30 days, and 12 mo.

§ A 4-dose schedule of Engerix administered in 2 1 mL doses (40 µg) on a 0-, 1-, 2-, and 6-mo schedule is recommended for adult hemodialysis patients.

From Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al: Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, MMWR 67(1):1–29, 2018, Table 4, p. 13.

Household, sexual, and needle-sharing contacts of patients with chronic HBV infection should be identified and vaccinated if they are susceptible to HBV infection. Patients should be advised about the perinatal and intimate contact risk of transmission of HBV. HBV is not spread by breastfeeding, kissing, hugging, or sharing water or utensils. Children with HBV should not be excluded from school, play, childcare, or work, unless they are prone to biting. A support group might help children to cope better with their disease. Families should not feel obligated to disclose the diagnosis as this information may lead to prejudice or mistreatment of the patient or the patient's family. All patients positive for HBsAg should be reported to the state or local health department, and chronicity is diagnosed if they remain positive past 6 mo HBIG.

HBIG is indicated only for specific postexposure circumstances and provides only temporary protection (3-6 mo). It plays a pivotal role in preventing perinatal transmission when administered within 12 hr of birth.

Universal Vaccination

Two single-antigen vaccines (Recombivax HB and Engerix-B) are approved for children and are the only preparations approved for infants younger than age 6 mo. Three combination vaccines can be used for subsequent immunization dosing and enable integration of the HBV vaccine into the regular immunization schedule. The safety profile of HBV vaccine is excellent. The most reported side effects are pain at the injection site (up to 29% of cases) and fever (up to 6% of cases). Seropositivity is >95% with all vaccines, achieved after the second dose in most patients. The third dose serves as a booster and may have an effect on maintaining long-term immunity. In immunosuppressed patients and infants whose birthweight is <2,000 g, a fourth dose is recommended (the birth dose does not count as part of the 3-dose series) and these infants should be checked for anti-HBs and HBsAg after completing these shots. In this group of infants, if the anti-HBs level is <10 mIU/mL, they should repeat the 3-dose series. Despite declines in the anti-HBs titer in time, most healthy vaccinated persons remain protected against HBV infection.

Current HBV vaccination recommendations are as noted in Tables 385.9 to 385.11 .

Postvaccination testing for HBsAg and anti-HBs should be done at 9-18 mo. If the result is positive for anti-HBs, the child is immune to HBV. If the result is positive for HBsAg only, the parent should be counseled, and the child evaluated by a pediatric hepatologist. If the result is negative for both HBsAg and anti-HBs, a second complete hepatitis B vaccine series should be administered, followed by testing for anti-HBs to determine if subsequent doses are needed.

Administration of 4 doses of vaccine is permissible when combination vaccines are used after the birth dose; this does not impact vaccine response.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis for prevention of hepatitis B infection depend on the conditions under which the person is exposed to HBV (see Table 385.11 ). Vaccination should never be postponed if written records of the exposed person's immunization history are not available, but every effort should still be made to obtain those records.

Special Populations

Patients with cirrhosis may not respond as well to the HBV vaccine and repeating anti-HBs titers should be performed. Adult studies suggest higher dosage or shorter interval between dosages may increase the immunization effectiveness. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease frequently have not been immunized, or did not develop complete immunity to HBV, as demonstrated by inadequate anti-HBs levels. These patients may be at risk for fulminant HBV (reactivation) when immunosuppression is started as part of their treatment regimen, specifically with biologic agents such as infliximab.

Prognosis

In general, the outcome after acute HBV infection is favorable, despite a risk of ALF. The risk of developing chronic infection brings the risks of liver cirrhosis and HCC to the forefront. Perinatal transmission leading to chronicity is responsible for the high incidence of HCC in young adults in endemic areas. Importantly, HBV infection and its complications are effectively controlled and prevented with vaccination and multiple clinical trials are ongoing in an effort to improve and guide treatment regimens.

Hepatitis C

Etiology

HCV is a single-stranded RNA virus, classified as a separate genus within the Flaviviridae family, with marked genetic heterogeneity. It has 6 major genotypes and numerous subtypes and quasi-species, which permit the virus to escape host immune surveillance. Genotype variation might partially explain the differences in clinical course and response to treatment. Genotype 1b is the most common genotype in the United States and is the least responsive to the approved pediatric medications.

Epidemiology

In the United States, HCV infection, the most common cause of chronic liver disease in adults, is responsible for 8,000-10,000 deaths per year. Approximately 4 million people in the United States and 170 million people worldwide are estimated to be infected with HCV. Approximately 85% of infected adults remain chronically infected. In children, seroprevalence of HCV is 0.2% in those younger than age 11 yr and 0.4% in children age 11 yr or older. However, even more children may be infected as only a small percentage of HCV-infected children are identified, and an even smaller number subsequently receive treatment. Appropriate identification, and screening, for infected individuals should be implemented.

Risk factors for HCV transmission in the United States included blood transfusion before 1992 as the most common route of infection, but, with current blood donor screening practices, the risk of HCV transmission is approximately 0.001% per unit transfused. Illegal drug use with exposure to blood or blood products from HCV-infected persons accounts for more than half of adult cases in the United States. Sexual transmission, especially through multiple sexual partners, is the second most common cause of infection. Other risk factors include occupational exposure, but approximately 10% of new infections have no known transmission source. In children, perinatal transmission is the most prevalent mode of transmission (see Table 385.1 ). Perinatal transmission occurs in up to 5% of infants born to viremic mothers. HIV coinfection and high viremia titers (HCV RNA-positive) in the mother can increase the transmission rate to 20%. The incubation period is 7-9 wk (range: 2-24 wk).

Pathogenesis

The pattern of acute hepatic injury is indistinguishable from that of other hepatotropic viruses. In chronic cases, lymphoid aggregates or follicles in portal tracts are found, either alone or as part of a general inflammatory infiltrate of the portal areas. Steatosis is also often seen in these liver specimens. HCV appears to cause injury primarily by cytopathic mechanisms, but immune-mediated injury can also occur. The cytopathic component appears to be mild because the acute illness is typically the least severe of all hepatotropic virus infections.

Clinical Manifestations

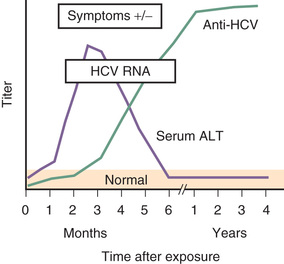

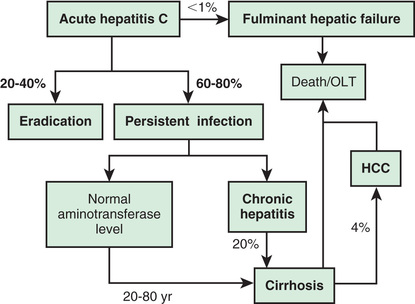

Acute HCV infection tends to be mild and insidious in onset (Fig. 385.4 ; see also Table 385.1 ). ALF rarely occurs. HCV is the most likely of all these viruses to cause chronic infection (Fig. 385.5 ). Of affected adults, <15% clear the virus; the rest develop chronic hepatitis. In pediatric studies, 6–19% of children achieved spontaneous sustained clearance of the virus during a 6-yr follow-up.

Chronic HCV infection is also clinically silent until a complication develops. Serum aminotransferase levels fluctuate and are sometimes normal, but histologic inflammation is universal. Progression of liver fibrosis is slow over several years, unless comorbid factors are present, which can accelerate fibrosis progression. Approximately 25% of infected patients ultimately progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, and, occasionally, primary HCC within 20-30 yr of the acute infection. Although progression is rare within the pediatric age range, cirrhosis and HCC from HCV have been reported in children. The long-term morbidities constitute the rationale for diagnosis and treatment in children with HCV.

Chronic HCV infection can be associated with small vessel vasculitis and is a common cause of essential mixed cryoglobulinemia. Other extrahepatic manifestations, predominantly seen in adults, include cutaneous vasculitis, porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, peripheral neuropathy, cerebritis, polyarthritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and nephrotic syndrome. Antibodies to smooth muscle, antinuclear antibodies, and low thyroid hormone levels may also be present.

Diagnosis

Clinically available assays for detection of HCV infection are based on detection of antibodies to HCV antigens or detection of viral RNA (see Table 385.3 ); neither can predict the severity of liver disease.

The most widely used serologic test is the third-generation enzyme immunoassay to detect anti-HCV. The predictive value of this assay is greatest in high-risk populations, but the false-positive rate can be as high as 50–60% in low-risk populations. False-negative results also occur because antibodies remain negative for as long as 1-3 mo after clinical onset of illness. Anti-HCV is not a protective antibody and does not confer immunity; it is usually present simultaneously with the virus.

The most commonly used virologic assay for HCV is a PCR assay, which permits detection of small amounts of HCV RNA in serum and tissue samples within days of infection. The qualitative PCR detection is especially useful in patients with recent or perinatal infection, hypogammaglobulinemia, or immunosuppression and is highly sensitive. The quantitative PCR aids in identifying patients who are likely to respond to therapy and in monitoring response to therapy.

Screening for HCV should include all patients with the following risk factors: history of illegal drug use (even if only once), receiving clotting factors made before 1987 (when inactivation procedures were introduced) or blood products before 1992, hemodialysis, idiopathic liver disease, and children born to HCV-infected women (qualitative PCR in infancy and anti-HCV after 12-18 mo of age). In children, it is also important to consider whether the mother has any of the risk factors noted above that would increase her possibility of developing HCV. Routine screening of all pregnant women is currently not recommended. The Centers for Disease Control now recommends that all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 be screened.

Determining HCV genotype is also important, particularly when therapy is considered, because the response to the current therapeutic agents varies greatly. Genotype 1 traditionally responded poorly to therapy while genotypes 2 and 3 had a more favorable response. Newer agents, however, have led to changes in the treatment duration and anticipated outcome (as discussed later).

Aminotransferase levels typically fluctuate during HCV infection and do not correlate with the degree of liver fibrosis. A liver biopsy was previously the only means to assess the presence and extent of hepatic fibrosis, outside of overt signs of chronic liver disease. Newer noninvasive modalities using ultrasound or magnetic resonance elastography, however, are now used to estimate the degree of fibrosis and decrease the need for biopsy. This technology coupled with newer drug regimens have eliminated the need for liver biopsy in many cases of HCV. A liver biopsy is now primarily indicated to rule out other causes of overt liver disease.

Complications

The risk of ALF caused by HCV is low, but the risk of chronic hepatitis is the highest of all the hepatitis viruses. In adults, risk factors for progression to hepatic fibrosis include older age, obesity, male sex, and even moderate alcohol ingestion (two 1 oz. drinks per day). Progression to cirrhosis or HCC is a major cause of morbidity and the most common indication for liver transplantation in adults in the United States.

Treatment

In adults, peginterferon (subcutaneous, weekly) combined with ribavirin (oral, daily) was standard therapy until 2012 for genotype 1. Currently recommended first-line adult therapy for HCV includes taking 1 or 2 oral medications with direct-acting antiviral properties, for 12-24 wk dependent on HCV genotype and other clinical factors. Studies show these treatments are more effective and better tolerated, and these same medications are currently being evaluated in children and adolescents.

Traditionally, patients most likely to respond had mild hepatitis, shorter duration of infection, low viral titers, and either genotype 2 or 3 virus. Patients with genotype 1 virus responded poorly. Response to peginterferon alfa/ribavirin may be predicted by single-nucleotide polymorphisms near the interleukin 28B gene, but with these newer treatment regimens excellent response rates are being reported with shorter duration, IFN-free regimens.

The goal of treatment is to achieve a sustained viral response (SVR), as defined by the absence of viremia at a variable period after stopping the medications; SVR is associated with improved histology and decreased risk of morbidities.

The natural history of HCV infection in children is still being defined. It is believed that children have a higher rate of spontaneous clearance than adults (up to 45% by age 19 yr). A multicenter study followed 359 children infected with HCV over 10 yr. Only 7.5% had cleared the virus, and 1.8% progressed to decompensated cirrhosis. Treatment in adults with acute HCV in a pilot study showed an 88% SVR in genotype 1 subjects (treated with IFN and ribavirin for 24 wk). Such data, if confirmed, could raise the question whether children, with shorter duration of infection and fewer comorbid conditions than their adult counterparts, could be ideal candidates for treatment. Given the adverse effects of currently available therapy, this strategy is not recommended outside of clinical trials.

Peginterferon (Schering), IFN-α2b, and ribavirin are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in children older than 3 yr of age with chronic hepatitis C. Studies of IFN monotherapy in children demonstrated a higher SVR than in adults, with better compliance and fewer side effects. An SVR up to 49% for genotype 1 was achieved in multiple studies. Factors associated with a higher likelihood of response are age younger than 12 yr, genotypes 2 and 3, and, in patients with genotype 1b, an RNA titer of <2 million copies/mL of blood, and viral response (PCR at wk 4 and 12 of treatment). Side effects of medications lead to discontinuation of treatment in a high proportion of patients; these include influenza-like symptoms, anemia, and neutropenia. Long-term effects of these medicines also need to be evaluated as significant differences were noted in children's weight, height, body mass index, and body composition. Most of these delays improved following cessation of treatment, but height z-scores continued to lag behind.

Treatment may be considered for children infected with genotypes 2 and 3, because they have an 80–90% response rate to therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin. If the child has genotype 1b virus, the treatment choice remains more controversial as newer regimens are quickly becoming available.

Pediatric guidelines recommend treatment to eradicate HCV infection, prevent progression of liver disease and development of HCC, and to remove the stigma associated with HCV. Treatment should be considered for patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis or injury on liver biopsy. One approved treatment consists of 24-48 wk of peginterferon and ribavirin (therapy should be stopped if still detectable on viral PCR at 24 wk of therapy). In addition, sofosbuvir alone or in combination with ledipasvir has FDA approval for children ages 12-17 yr. The combination is indicated for HCV genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6, while sofosbuvir with ribavirin is indicated for HCV genotypes 2 or 3; both regimens are used in children with mild or no cirrhosis.

Newer Treatments

Varying IFN-free regimens are now available for adults for all HCV genotypes allowing even greater likelihood of achieving viral eradication, with completely oral medication regimens, and without the use of IFN and its attendant side effects. With the rapid development of new medications and regimens, frequent review of up-to-date resources, such as www.hcvguidelines.org , will be vital to provide optimal care (Table 385.12 ).

Table 385.12

Ongoing Studies With Direct Acting Antiviral Combinations in Children With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection

| GENOTYPE | ESTIMATED ENROLMENT | AGE RANGE (YR) | IDENTIFIER | COMPLETION | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sofosbuvir + ledipasvir, with or without ribavirin | 1,4,5,6 | 222 | 3–17 | NCT02249182 | July 2018 |

| Sofosbuvir + ribavirin | 2,3 | 104 | 3–17 | NCT02175758 | April 2018 |

| Ombitasvir + paritaprevir + ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir, with or without ribavirin | 1,4 | 74 | 3–17 | NCT02486406 | September 2019 |

| Sofosbuvir + daclatasvir | 4 | 40 | 8–17 | NCT03080415 | June 2018 |

| Sofosbuvir + ledipasvir | 1,4 | 40 | 12–17 | NCT02868242 | April 2019 |

| Sofosbuvir + velpatasvir | 1–6 | 200 | 3–17 | NCT03022981 | December 2019 |

| Glecaprevir + pibrentasvir | 1–6 | 110 | 3–17 | NCT03067129 | May 2022 |

| Gratisovir + ribavirin | 1–6 | 41 | 10–17 | NCT02985281 | June 2017 |

From Indolfi G, Serranti D, Resti M: Direct-acting antivirals for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. Lancet Child Adolesc 2:298-304, 2018 (Table 1, p. 299).

Prevention

No vaccine is yet available to prevent HCV, although ongoing research suggests this will be possible in the future. Currently available Ig preparations are not beneficial, likely because preparations produced in the United States do not contain antibodies to HCV because blood and plasma donors are screened for anti-HCV and excluded from the donor pool. Broad neutralizing antibodies to HCV were found to be protective and might pave the road for vaccine development.

Once HCV infection is identified, patients should be screened yearly with a liver ultrasound and serum α-fetoprotein for HCC, as well as for any clinical evidence of liver disease. Vaccinating the affected patient against HAV and HBV will prevent superinfection with these viruses and the increased risk of developing severe liver failure.

Prognosis

Viral titers should be checked yearly to document spontaneous remission. Most patients develop chronic hepatitis. Progressive liver damage is higher in those with additional comorbid factors such as alcohol consumption, viral genotypic variations, obesity, and underlying genetic predispositions. Referral to a pediatric hepatologist is strongly advised to take advantage of up-to-date monitoring regimens and to optimize their enrollment in treatment protocols when available.

Hepatitis D

Etiology

HDV, the smallest known animal virus, is considered defective because it cannot produce infection without concurrent HBV infection. The 36 nm diameter virus is incapable of making its own coat protein; its outer coat is composed of excess HBsAg from HBV. The inner core of the virus is single-stranded circular RNA that expresses the HDV antigen.

Epidemiology

HDV can cause an infection at the same time as the initial HBV infection (coinfection), or HDV can infect a person who is already infected with HBV (superinfection). Transmission usually occurs by intrafamilial or intimate contact in areas of high prevalence, which are primarily developing countries (see Table 385.1 ). In areas of low prevalence, such as the United States, the parenteral route is far more common. HDV infections are uncommon in children in the United States but must be considered when ALF occurs. The incubation period for HDV superinfection is approximately 2-8 wk; with coinfection, the incubation period is similar to that of HBV infection.

Pathogenesis

Liver pathology in HDV-associated hepatitis has no distinguishing features except that damage is usually severe. In contrast to HBV, HDV causes injury directly by cytopathic mechanisms. The most severe cases of HBV infection appear to result from coinfection of HBV and HDV.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms of hepatitis D are similar to, but usually more severe than, those of the other hepatotropic viruses. The clinical outcome for HDV infection depends on the mechanism of infection. In coinfection, acute hepatitis, which is much more severe than for HBV alone, is common, but the risk of developing chronic hepatitis is low. In superinfection, acute illness is rare and chronic hepatitis is common. The risk of ALF is highest with superinfection. Hepatitis D should be considered in any child who experiences ALF.

Diagnosis

HDV has not been isolated and no circulating antigen has been identified. The diagnosis is made by detecting IgM antibody to HDV; the antibodies to HDV develop approximately 2-4 wk after coinfection and approximately 10 wk after a superinfection. A test for anti-HDV antibody is commercially available. PCR assays for viral RNA are available as research tools (see Table 385.2 ).

Treatment

The treatment is based on supportive measures once an infection is identified. There are no specific HDV-targeted treatments to date. The treatment is mostly based on controlling and treating HBV infection, without which HDV cannot induce hepatitis. Small research studies suggest that IFN is the preferred treatment regimen, but ongoing studies still seek the ideal management strategy and the regimen should be personalized for each patient.

Prevention

There is no vaccine for hepatitis D. Because HDV replication cannot occur without hepatitis B coinfection, immunization against HBV also prevents HDV infection. Hepatitis B vaccines and HBIG are used for the same indications as for hepatitis B alone.

Hepatitis E

Etiology

HEV has been cloned using molecular techniques. This RNA virus has a nonenveloped sphere shape with spikes and is similar in structure to the caliciviruses.

Epidemiology

Hepatitis E is the epidemic form of what was formerly called non-A, non-B hepatitis. Transmission is fecal–oral (often waterborne) and is associated with shedding of 27-34 nm particles in the stool (see Table 385.1 ). The highest prevalence of HEV infection has been reported in the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Mexico, especially in areas with poor sanitation. The prevalence, however, appears to be increasing in the United States and other developed countries and has been postulated to be the most common cause of acute hepatitis and jaundice in the world. The mean incubation period is approximately 40 days (range: 15-60 days).

Pathogenesis

HEV appears to act as a cytopathic virus. The pathologic findings are similar to those of the other hepatitis viruses.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical illness associated with HEV infection is similar to that of HAV but is often more severe. As with HAV, chronic illness does not occur—the sole exception noted to date is chronic hepatitis E occurring in immunosuppressed patients (e.g., post-transplant). In addition to often causing a more severe episode than HAV, HEV tends to affect older patients, with a peak age between 15 and 34 yr. HEV is a major pathogen in pregnant women, in whom it causes ALF with a high fatality incidence. HEV could also lead to decompensation of preexisting chronic liver disease.

Diagnosis

Recombinant DNA technology has resulted in development of antibodies to HEV particles, and IgM and IgG assays are available to distinguish between acute and resolved infections (see Table 385.3 ). IgM antibody to viral antigen becomes positive after approximately 1 wk of illness. Viral RNA can be detected in stool and serum by PCR.

Prevention

A recombinant hepatitis E vaccine is highly effective in adults. No evidence suggests that immune-globulin is effective in preventing HEV infections. Ig pooled from patients in endemic areas might prove to be effective.

Approach to Acute or Chronic Hepatitis

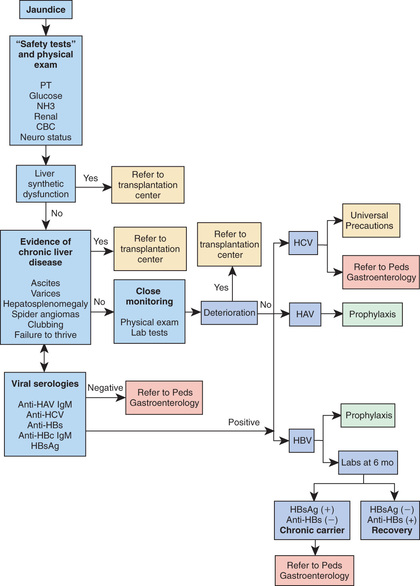

Identifying deterioration of the patient with acute hepatitis and the development of ALF is a major contribution of the primary pediatrician (Fig. 385.6 ). If ALF is identified, the clinician should immediately refer the patient to a transplantation center; this can be lifesaving.

Once chronic infection is identified, close follow-up and referral to a pediatric hepatologist is recommended to enroll the patient in appropriate treatment trials. Treatment of chronic HBV and HCV in children should preferably be delivered within, or using data from, pediatric controlled trials as indications, timing, regimen, and outcomes remain to be defined and cannot be extrapolated from adult data. All patients with chronic viral hepatitis should avoid, as much as possible, further insult to the liver; HAV vaccine is recommended. Patients must avoid alcohol consumption and obesity, and they should exercise care when taking new medications, including nonprescription drugs and herbal medications.

International adoption and ease of travel continue to change the epidemiology of hepatitis viruses. In the United States, chronic HBV and HCV have a high prevalence among international adoptee patients; vigilance is required to establish early diagnosis in order to offer appropriate treatment as well as prophylactic measures to limit viral spread.

Chronic hepatitis can be a stigmatizing disease for children and their families. The pediatrician should offer, with proactive advocacy, appropriate support for them as well as needed education for their social circle. Scientific data and information about support groups are available for families on the websites for the American Liver Foundation (www.liverfoundation.org ) and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (www.naspghan.org ), as well as through pediatric gastroenterology centers.