Retropharyngeal Abscess, Lateral Pharyngeal (Parapharyngeal) Abscess, and Peritonsillar Cellulitis/Abscess

Diane E. Pappas, J. Owen Hendley †

The retropharyngeal and the lateral pharyngeal lymph nodes that drain the mucosal surfaces of the upper airway and digestive tracts are located in the neck within the retropharyngeal space (located between the pharynx and the cervical vertebrae and extending down into the superior mediastinum) and the lateral pharyngeal space (bounded by the pharynx medially, the carotid sheath posteriorly, and the muscles of the styloid process laterally). The lymph nodes in these deep neck spaces communicate with each other, allowing bacteria from either cellulitis or node abscess to spread to other nodes. Infection of the nodes usually occurs as a result of extension from a localized infection of the oropharynx. A retropharyngeal abscess can also result from penetrating trauma to the oropharynx, dental infection, and vertebral osteomyelitis. Once infected, the nodes may progress through 3 stages: cellulitis, phlegmon, and abscess. Infection in the retropharyngeal and lateral pharyngeal spaces can result in airway compromise or posterior mediastinitis, making timely diagnosis important. Incidence based on analysis of a 2009 national database is estimated to be 4.6 per 100,000 children in the United States.

Retropharyngeal and Lateral Pharyngeal Abscess

Retropharyngeal abscess occurs most commonly in children younger than 3-4 yr of age; as the retropharyngeal nodes involute after 5 yr of age, infection in older children and adults is much less common. In the United States, abscess formation occurs most commonly in winter and early spring. Males are affected more often than females and approximately two-thirds of patients have a history of recent ear, nose, or throat infection.

Clinical manifestations of retropharyngeal abscess are nonspecific and include fever, irritability, decreased oral intake, and drooling. Neck stiffness, torticollis, and refusal to move the neck may also be present. The verbal child might complain of sore throat and neck pain. Other signs can include muffled voice, stridor, respiratory distress, or even obstructive sleep apnea. Physical examination can reveal bulging of the posterior pharyngeal wall, although this is present in <50% of infants with retropharyngeal abscess. Cervical lymphadenopathy may also be present.

Lateral pharyngeal abscess commonly presents as fever, dysphagia, and a prominent bulge of the lateral pharyngeal wall, sometimes with medial displacement of the tonsil.

The differential diagnosis includes acute epiglottitis and foreign body aspiration. In the young child with limited neck mobility, meningitis must also be considered. Other possibilities include lymphoma, hematoma, and vertebral osteomyelitis.

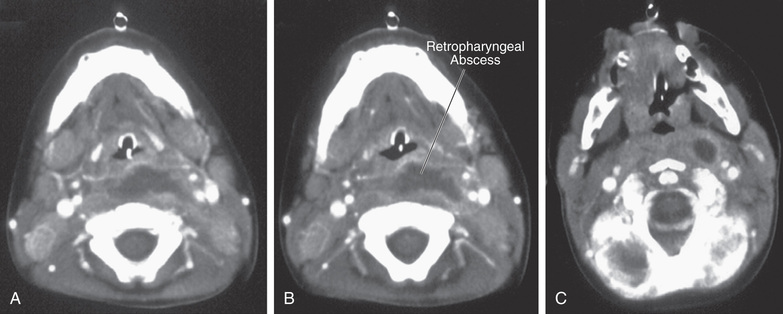

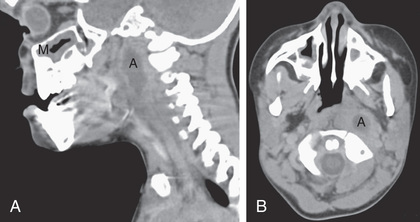

Incision and drainage and culture of an abscessed node provides the definitive diagnosis, but CT can be useful in identifying the presence of a retropharyngeal, lateral pharyngeal, or parapharyngeal abscess (Figs. 410.1 and 410.2 ). Deep neck infections can be accurately identified and localized with CT scans, but CT accurately identifies abscess formation in only 63% of patients. Soft-tissue neck films taken during inspiration with the neck extended might show increased width or an air–fluid level in the retropharyngeal space. CT with contrast medium enhancement can reveal central lucency, ring enhancement, or scalloping of the walls of a lymph node. Scalloping of the abscess wall is thought to be a late finding and predicts abscess formation.

Retropharyngeal and lateral pharyngeal infections are most often polymicrobial; the usual pathogens include group A streptococcus (see Chapter 210 ), oropharyngeal anaerobic bacteria (see Chapter 240 ), and Staphylococcus aureus (see Chapter 208.1 ). In children younger than age 2 yr, there has been an increase in the incidence of retropharyngeal abscess, particularly with S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant strains. Mediastinitis may be identified on CT in some of these patients. Other pathogens can include Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.

Treatment options include intravenous antibiotics with or without surgical drainage. A third-generation cephalosporin combined with ampicillin-sulbactam or clindamycin to provide anaerobic coverage is effective. The increasing prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus can influence empiric antibiotic therapy. Studies show that >50% of children with retropharyngeal or lateral pharyngeal abscess as identified by CT can be successfully treated without surgical drainage; the older the child, the more likely it is that antimicrobial treatment alone will be successful. Drainage is necessary in the patient with respiratory distress or failure to improve with intravenous antibiotic treatment. The optimal duration of treatment is unknown; the typical treatment course is intravenous antibiotic therapy for several days until the patient has begun to improve, followed by a course of oral antibiotics.

Complications of retropharyngeal or lateral pharyngeal abscess include significant upper airway obstruction, rupture leading to aspiration pneumonia, and extension to the mediastinum. Thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and erosion of the carotid artery sheath can also occur.

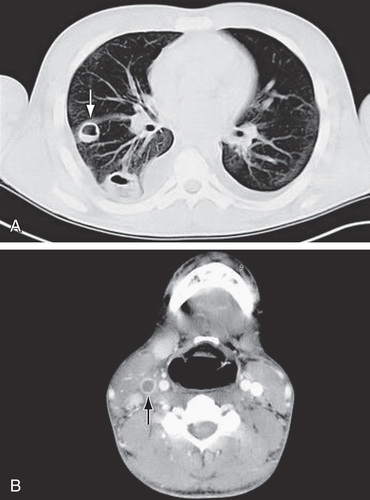

An uncommon but characteristic infection of the parapharyngeal space is Lemierre disease, in which infection from the oropharynx extends to cause septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and embolic abscesses in the lungs (Fig. 410.3 ). The causative pathogen is Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic bacterial constituent of the oropharyngeal flora. The typical presentation is that of a previously healthy adolescent or young adult with a history of recent pharyngitis who becomes acutely ill with fever, hypoxia, tachypnea, and respiratory distress. Chest radiography demonstrates multiple cavitary nodules, often bilateral and often accompanied by pleural effusion. Blood culture may be positive. Treatment involves prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy with penicillin or cefoxitin; surgical drainage of extrapulmonary metastatic abscesses may be necessary (see Chapters 409 and 411 ).

Peritonsillar Cellulitis and/or Abscess

Peritonsillar cellulitis and/or abscess, which is relatively common compared to the deep neck infections, is caused by bacterial invasion through the capsule of the tonsil, leading to cellulitis and/or abscess formation in the surrounding tissues. The typical patient with a peritonsillar abscess is an adolescent with a recent history of acute pharyngotonsillitis. Clinical manifestations include sore throat, fever, trismus, muffled or garbled voice, and dysphagia. Physical examination reveals an asymmetric tonsillar bulge with displacement of the uvula. An asymmetric tonsillar bulge is diagnostic, but it may be poorly visualized because of trismus. CT is helpful for revealing the abscess, but recent small studies in adults and children have demonstrated that ultrasound may be used to differentiate peritonsillar abscess from peritonsillar cellulitis and avoids radiation exposure, as well as the need for sedation that CT often necessitates in children. Group A streptococci and mixed oropharyngeal anaerobes are the most common pathogens, with more than four bacterial isolates per abscess typically recovered by needle aspiration.

Treatment includes surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy effective against group A streptococci and anaerobes. Surgical drainage may be accomplished through needle aspiration, incision and drainage, or tonsillectomy. Needle aspiration can involve aspiration of the superior, middle, and inferior aspects of the tonsil to locate the abscess. Intraoral ultrasound can be used to diagnose and guide needle aspiration of a peritonsillar abscess. General anesthesia may be required for the uncooperative patient. Approximately 95% of peritonsillar abscesses resolve after needle aspiration and antibiotic therapy. A small percentage of these patients require a repeat needle aspiration. The 5% with infections that fail to resolve after needle aspiration require incision and drainage. Tonsillectomy should be considered if there is failure to improve within 24 hr of antibiotic therapy and needle aspiration, history of recurrent peritonsillar abscess or recurrent tonsillitis, or complications from peritonsillar abscess. The feared, albeit rare, complication is rupture of the abscess, with resultant aspiration pneumonitis. There is a 10% recurrence risk for peritonsillar abscess.