Definitions and Classification of Hemolytic Anemias

Matthew D. Merguerian, Patrick G. Gallagher

Hemolysis is defined as the premature destruction of red blood cells (RBCs). Anemia results when the rate of destruction exceeds the capacity of the marrow to produce additional RBCs. Normal RBC survival time is 110-120 days (half-life: 55-60 days), and thus approximately 0.85% of the most senescent RBCs are removed and replaced each day. During hemolysis, RBC survival is shortened, the RBC count falls, erythropoietin is increased, and marrow erythropoietic activity is stimulated. This sequence leads to compensatory erythroid hyperplasia with increased RBC production, reflected by an increase in the reticulocyte count. The marrow can increase its output 2-3–fold acutely, with a maximum of 6-8–fold in chronic hemolysis. The reticulocyte percentage can be corrected to measure the magnitude of marrow production in response to hemolysis as follows:

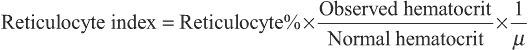

Reticulocyte index=Reticulocyte%×Observed hematocritNormal hematocrit×1μ

where µ is a maturation factor of 1-3 related to the severity of the anemia (Fig. 484.1 ). The normal reticulocyte index is 1.0; therefore the index measures the fold increase in erythropoiesis (e.g., 2-fold, 3-fold). Because the reticulocyte index is essentially a measure of RBC production per day, the maturation factor, µ, provides this correction.

When hemolysis is chronic, compensatory erythroid hyperplasia may lead to significant expansion of the medullary spaces at the expense of cortical bone. This effect is particularly prominent in children with severe chronic hemolytic anemia, such as thalassemia. These changes may be evident on physical examination or radiography of the skull and long bones. In severe cases, there is increased propensity for long-bone fracture. Hemolysis also leads to increased degradation of hemoglobin. This process can result in indirect hyperbilirubinemia, increased biliary excretion of heme pigment derivatives, and formation of bilirubinate gallstones.

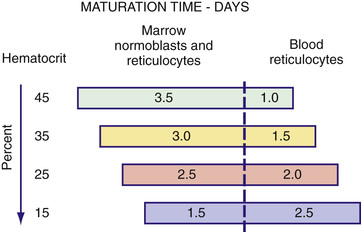

During hemolysis, heme-binding proteins in the plasma are altered (Fig. 484.2 ). Hemoglobin binds to haptoglobin and hemopexin, both of which are cleared more rapidly as heme-bound complexes. Oxidized heme binds to albumin to form methemalbumin, which is increased in the plasma during hemolysis. When the capacity of these heme-binding molecules is exceeded, free hemoglobin appears in the plasma. Free hemoglobin in the plasma is considered prima facie evidence of intravascular hemolysis. Free hemoglobin dissociates into dimers and is filtered by the kidneys. When the tubular reabsorptive capacity of the kidneys for hemoglobin is exceeded, free hemoglobin appears in the urine. Even in the absence of hemoglobinuria, iron loss can result from reabsorbed hemoglobin and the shedding of renal epithelial cells in which the iron from hemoglobin is stored as hemosiderin. This iron loss can lead to iron deficiency during chronic intravascular hemolysis. The ongoing presence of circulating free hemoglobin and hemin have been linked to vascular disease, including pulmonary hypertension, thrombosis, inflammation, and impaired renal function.

Hemolytic anemia may be classified in several different ways. It can be classified by whether there is a cellular abnormality of the erythrocyte (intrinsic or intracorpuscular) or an extracellular abnormality of the erythrocyte (extrinsic or extracorpuscular) resulting from antibodies, mechanical factors, or plasma factors. Hemolytic anemia can be also classified as inherited or acquired , whether there is immune-mediated (immune ) or nonimmune-mediated (nonimmune ) hemolysis, whether hemolysis is acute or chronic , or whether hemolysis occurs in the vasculature (intravascular ) or in the reticuloendothelial system (extravascular ) (Tables 484.1 and 484.2 ). Most intrinsic defects are inherited, such as hereditary disorders of the erythrocyte membrane, metabolic defects of the erythrocyte, and hemoglobin disorders (though paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria is acquired). Most extrinsic defects are acquired, with examples including immune-mediated mechanisms such as warm and cold agglutinin hemolysis and nonimmune causes such as systemic diseases, drug- or toxin-mediated effects, and mechanical destruction of erythrocytes (although abetalipoproteinemia with acanthocytosis is inherited).

Table 484.1

Classification of Nonimmune Hemolytic Anemias

| DISORDERS/CAUSES | LABORATORY FINDINGS | DIAGNOSTIC TEST |

|---|---|---|

| CONGENITAL DISORDERS | ||

| Membrane Disorders | ||

| Hereditary spherocytosis | Spherocytes | EMA binding, osmotic fragility |

| Hereditary elliptocytosis | Elliptocytes | Blood smear |

| Hereditary pyropoikilocytosis | Microcytes, fragments | |

| Hemoglobin Disorders | ||

| Sickle cell disease | Sickle cells, targets | Hemoglobin electrophoresis |

| Unstable hemoglobins | Bite cells | Supravital stain, heat or alcohol stability test |

| Enzyme Disorders | ||

| G6PD deficiency | Bite cells, blister cells | Supravital stain, G6PD level |

| Others | Variable | Individual enzyme levels |

| ACQUIRED DISORDERS | ||

| Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemias | ||

| TTP, HUS, DIC, cancer, heart valves | Schistocytes, red blood cell fragments | Targeted to diagnosis |

| Infections | ||

| Malaria, babesiosis, Clostridium perfringens | Parasite (malaria, babesiosis) | Giemsa stain (babesiosis) |

| Toxins and Physical Agents | ||

| Arsenic, lead, copper | Basophilic stippling (lead) | Element levels |

| Insert, spider, snake venoms | Schistocytes, fragments | Targeted to diagnosis |

| Systemic Diseases | ||

| Liver disease | Acanthocytes, target cells | Liver function tests |

| Burns | Spherocytes, blister cells, fragments | Targeted to diagnosis |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | Variable | Flow cytometry |

DIC, Disseminated intravascular coagulation; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

From Cornett PA: Hemolytic anemia. In Conn's current therapy, Philadelphia, 2017, Elsevier (Table 1, p 374).

Initial evaluation of a patient with suspected hemolytic anemia includes a detailed history of the current illness with attention to coexisting diagnoses, past medical history, family history, detailed list of medications, or recent exposures (Table 484.3 ). A complete blood count with erythrocyte indices, peripheral blood smear examination, reticulocyte count, and a direct antiglobulin test should be obtained (Table 484.4 ). Increased indirect bilirubin, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase, or serum decreased haptoglobin, indicating the presence of hemolysis, may also be obtained. Haptoglobin levels are favored by some because of the rapid decline in intravascular hemolysis, but are not specific. Haptoglobin levels may be decreased in cases of brisk extravascular hemolysis, may be significantly influenced by genetic variation, and may be an acute-phase reactant (resulting in normal concentrations in patients with concomitant infection or inflammation in the presence of hemolysis). These initial investigations will provide evidence that there is hemolysis and may provide clues to further diagnostic evaluations.