Hemoglobinopathies

Kim Smith-Whitley, Janet L. Kwiatkowski

Hemoglobin Disorders

Hemoglobin is a tetramer consisting of 2 pairs of globin chains. Abnormalities in these proteins are referred to as hemoglobinopathies.

More than 800 variant hemoglobins have been described. The most common and useful clinical classification of hemoglobinopathies is based on nomenclature associated with alteration of the involved globin chain. Two hemoglobin (Hb) gene clusters are involved in Hb production and are located at the end of the short arms of chromosomes 16 and 11. Their control is complex, including an upstream locus control region on each respective chromosome and an X-linked control site. On chromosome 16, there are 3 genes within the alpha (α) gene cluster: zeta (ζ), alpha 1 (α1 ), and alpha 2 (α2 ). On chromosome 11, there are 5 genes within the beta (β) gene cluster: epsilon (ε), gamma 1 (γ1 ), gamma 2 (γ2 ), delta (δ), and beta (β).

The order of gene expression within each cluster roughly follows the order of expression during the embryonic period, fetal period, and eventually childhood. After 8 wk of fetal life, the embryonic hemoglobins, Gower-1 (ζ2 ε2 ), Gower-2 (α2 ε2 ), and Portland (ζ2 γ2 ), are formed. At 9 wk of fetal life, the major hemoglobin is HbF (α2 γ2 ). HbA (α2 β2 ) first appears at approximately 1 mo of fetal life, but does not become the dominant hemoglobin until after birth, when HbF levels start to decline. HbA2 (α2 δ2 ) is a minor hemoglobin that appears shortly before birth and remains at a low level after birth. The final hemoglobin distribution pattern that occurs in childhood is not achieved until at least 6 mo of age and sometimes later. The normal hemoglobin pattern is ≥95% HbA, ≤3.5 HbA2 , and <2.5% HbF.

Sickle Cell Disease

Kim Smith-Whitley

Children with sickle cell disease should be followed by experts in the management of this disease, most often by pediatric hematologists. Medical care provided by a pediatric hematologist is also associated with a decreased frequency of emergency department (ED) visits and length of hospitalization when compared to patients who were not seen by a hematologist within the last year.

Pathophysiology

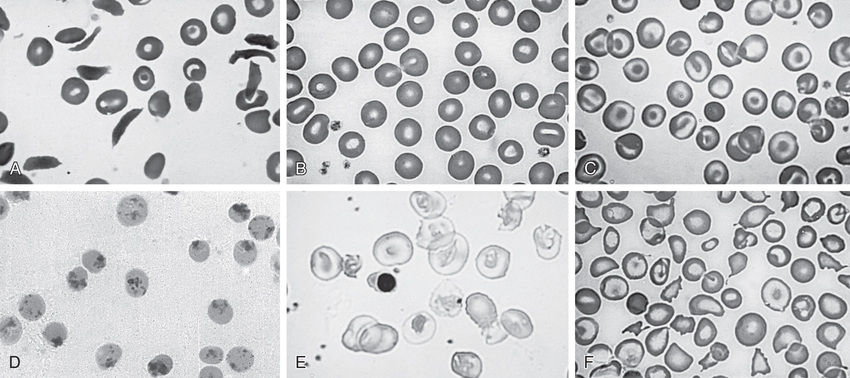

Hemoglobin S (HbS) is the result of a single base-pair change, thymine for adenine, at the 6th codon of the β-globin gene. This change encodes valine instead of glutamine in the 6th residue in the β-globin molecule. Sickle cell anemia (HbSS), homozygous HbSS, occurs when both β-globin alleles have the sickle cell mutation (βs). Sickle cell disease refers not only to patients with sickle cell anemia, but also to compound heterozygotes where one β-globin allele includes the sickle cell mutation and the 2nd β-globin allele includes a gene mutation other than the sickle cell mutation, such as HbC, β-thalassemia, HbD, and HbOArab . In sickle cell anemia, HbS is typically as high as 90% of the total hemoglobin, whereas in sickle cell disease, HbS is >50% of all hemoglobin.

In red blood cells (RBCs), the hemoglobin molecule has a highly specified conformation allowing for the transport of oxygen in the body. In the absence of globin-chain mutations, hemoglobin molecules do not interact with one another. However, the presence of HbS results in a conformational change in the Hb tetramer, and in the deoxygenated state, HbS molecules interact with each other, forming rigid polymers that give the RBC its characteristic “sickled” shape. The lung is the only organ capable of reversing the polymers, and any disease of the lung can be expected to compromise the degree of reversibility.

Intravascular sickling primarily occurs in the postcapillary venules and is a function of both mechanical obstruction by sickled erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes and increased adhesion between these elements and the vascular endothelium. Sickle cell disease is also an inflammatory disease based on nonspecific markers of inflammation, including, but not limited to, elevated baseline white blood cell (WBC) count and cytokines. Intraerythrocytic changes lead to a shortened RBC life span and hemolysis. Hemolysis leads to multiple changes, including altered nitric oxide metabolism and oxidant stress that contribute to endothelial dysfunction.

Diagnosis and Epidemiology

Every state in the United States has instituted a mandatory newborn screening program for sickle cell disease. Such programs identify newborns with the disease and provide prompt diagnosis and referral to providers with expertise in sickle cell disease for anticipatory guidance and the initiation of penicillin before 4 mo of age.

The most commonly used procedures for newborn diagnosis include thin-layer/isoelectric focusing (IEF) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Some laboratories perform genetic testing on specimens demonstrating abnormal hemoglobins. A confirmatory step is recommended, with all patients who have initial abnormal screens being retested during the first clinical visit. In addition, a complete blood cell count (CBC) and Hb phenotype determination is recommended for both parents to confirm the diagnosis and to provide an opportunity for genetic counseling. Infants who may have HbS-hereditary persistence fetal hemoglobin (HbSHPFH) but do not have full parental studies should have molecular testing for β-globin genotype before 12 mo of age. Table 489.1 correlates the initial hemoglobin phenotype at birth with the type of hemoglobinopathy.

Table 489.1

Various Newborn Sickle Cell Disease Screening Results With Baseline Hemoglobin

| NEWBORN SCREENING RESULTS: SICKLE CELL DISEASE* | POSSIBLE HEMOGLOBIN PHENOTYPE † | BASELINE HEMOGLOBIN RANGE AFTER AGE 5 YR | EXPERTISE IN HEMATOLOGY CARE REQUIRED |

|---|---|---|---|

| FS | SCD-SS | 6-11 g/dL | Yes |

| SCD-S β0 thal | 6-10 g/dL | Yes | |

| SCD-S β+ thal | 9-12 g/dL | Yes | |

| SCD-S δβ− thal | 10-12 g/dL | Yes | |

| S HPFH | 12-14 g/dL | Yes | |

| FSC | SCD-SC | 10-15 g/dL | Yes |

| FSA ‡ | SCD-S β+ thal | 9-12 g/dL | Yes |

| FS other | SCD-S β0 thal | 6-10 g/dL | Yes |

| SCD-SD, SOArab , SCHarlem , SLepore | Variable | Yes | |

| AFS ‡ § | SCD-SS | 6-10 g/dL | Yes |

| SCD-S β+ thal | 6-9 g/dL | Yes | |

| SCD-S β0 thal | 7-13 g/dL variable | Yes |

* Hemoglobins are reported in order of quantity.

† Requires confirmatory hemoglobin analysis after at least 6 mo of age and, if possible, β-globin gene testing or hemoglobin analysis from both parents for accurate diagnosis of hemoglobin phenotype.

‡ Sickle cell trait is another possible diagnosis

§ Impossible to determine the diagnosis because the infant most likely received a blood transfusion before testing.

A, Normal hemoglobin; C, hemoglobin C; F, fetal hemoglobin; HPFH, hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin; OArab , hemoglobin OArab ; S, sickle hemoglobin; SC, sickle-hemoglobin C; SCD, sickle cell disease; SS, homozygous sickle cell disease; thal, thalassemia.

In newborn screening programs, the hemoglobin with the greatest quantity is reported first, followed by other hemoglobins in order of decreasing quantity. Some states perform IEF initially on newborn blood samples, then use DNA probes to confirm abnormal hemoglobins found on IEF. In newborns with a hemoglobin analysis result of HbFS , the pattern supports HbSS, HbSHPFH, or HbSβ0 -thalassemia. In a newborn with a hemoglobin analysis of HbFSA , the pattern is supportive of the diagnosis of HbSβ+ -thalassemia. The diagnosis of HbSβ+ -thalassemia is confirmed if at least 50% of the hemoglobin is HbS, HbA is present, and the amount of HbA2 is elevated (typically >3.5%), although HbA2 is not elevated in the newborn period. In newborns with a hemoglobin analysis of HbFSC , the pattern supports a diagnosis of HbSC. In newborns with a hemoglobin analysis of HbFAS , the pattern supports a diagnosis of HbAS (sickle cell trait); however, in this circumstance, care must be taken to confirm that the newborn has not received a red cell transfusion before testing.

A newborn with a hemoglobin analysis of AFS either has been transfused with RBCs before collection of the newborn screen to account for the greater amount of HbA than HbF, or there has been an error. The patient may have either sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait and should be started on penicillin prophylaxis until the final diagnosis can be determined.

Given the implications of a diagnosis of sickle cell disease vs sickle cell trait in a newborn, the importance of repeating the Hb identification analysis in the patient and obtaining a Hb identification analysis and CBC to evaluate the peripheral blood smear and RBC parameters in the parents for genetic counseling cannot be overemphasized. Unintended mistakes do occur in state newborn screening programs. Newborns who have the initial phenotype of HbFS but whose final true phenotype is HbSβ+ -thalassemia have been described as one of the more common errors identified in newborn screening hemoglobinopathy programs. Determining an accurate phenotype is important for appropriate genetic counseling for the parents. In addition, distinguishing HbSS from HbSHPFH in the newborn period usually requires parental or genetic testing. In infants who maintain HbF percentages above 25% after 12 mo of age without evidence of hemolysis should have testing for β-globin gene deletions consistent with HPFH. These children have a much milder clinical course and do not require penicillin prophylaxis or hydroxyurea therapy.

If the parents are tested for sickle cell trait or hemoglobinopathy trait full disclosure to the parents must be provided, and in some circumstances the issue of paternity may be disclosed. For this reason and because of healthcare privacy, common practice is to always seek permission for the genetic testing and to report the hemoglobinopathy trait results back to each parent separately.

In the United States, sickle cell disease is the most common genetic disorder identified through the state-mandated newborn screening program, occurring in 1 : 2,647. In regard to race in the United States, sickle cell disease occurs in African Americans at a rate of 1 : 396 births and in Hispanics at a rate of 1 : 36,000 births. In the United States, an estimated 100,000 people are affected by sickle cell disease, with an ethnic distribution of 90% African American and 10% Hispanic. The U.S. sickle cell disease population represents a fraction of the worldwide burden of the disease, with global estimates of 312,000 neonates born annually with HbSS disease.

Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Sickle Cell Anemia (HbSS)

For a comprehensive discussion of the clinical management of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease, refer to National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) 2014 Expert Panel Report on the Evidence-based Management of Sickle Cell Disease (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/sickle-cell-disease-report.pdf ).

Fever and Bacteremia

Fever in a child with sickle cell anemia is a medical emergency, requiring prompt medical evaluation and delivery of antibiotics because of the increased risk of bacterial infection and subsequent high mortality rate. As early as 6 mo of age, infants with sickle cell anemia develop abnormal immune function because of splenic dysfunction. By 5 yr of age, most children with sickle cell anemia have complete functional asplenia. Regardless of age, all patients with sickle cell anemia are at increased risk of infection and death from bacterial infection, particularly encapsulated organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae , Haemophilus influenzae type b, and Neisseria meningitidis .

The rate of bacteremia in children with sickle cell disease presenting with fever is <1%. Several clinical strategies have been developed to manage children with sickle cell disease who present with fever. These strategies range from hospital admission for intravenous (IV) antimicrobial therapy to administering a third-generation cephalosporin in an ED or outpatient setting to patients without established risk factors for occult bacteremia (Table 489.2 ). Given the observation that the average time for a positive blood culture is <20 hr in children with sickle cell anemia, admission for 24 hr is probably the most prudent strategy for children and families who live out of town or who are identified as high risk for poor follow-up.

Outpatient management of fever without a source should be considered in children with the lowest risk of bacteremia and after appropriate cultures are obtained and IV ceftriaxone or another cephalosporin is given. Observation after antibiotic administration is important, because children who have sickle cell anemia treated with ceftriaxone can develop severe, rapid, and life-threatening immune hemolysis. In the event that Salmonella spp. or Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia occurs, strong consideration should be given to an evaluation for osteomyelitis with a bone scan, given the increased risk of osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell anemia compared to the general population. Screening laboratory and radiologic studies are strongly recommended to identify those at risk for transient red cell aplasia, acute splenic sequestration, and acute chest syndrome (ACS ), because many children with these diagnoses present to acute care settings with isolated fever. Screening children and caregivers for psychosocial factors that could impede their return to the hospital in the case of a positive blood culture is essential.

Aplastic Crisis

Human parvovirus B19 infection poses a unique threat for patients with sickle cell disease because this infection results in temporary red cell aplasia , limiting the production of reticulocytes and causing profound anemia (see Fig. 485.3 in Chapter 485 ). Any child with sickle cell disease, fever, and reticulocytopenia should be presumed to have parvovirus B19 infection until proven otherwise. Reticulocytosis and increased nucleated RBCs may be seen in the recovery phase. Testing for the presence of human parvovirus B19 with PCR testing is superior to using IgM and IgG titers. The acute exacerbation of anemia is treated conservatively using red cell transfusion when the patient becomes hemodynamically symptomatic or has a concurrent illness, such as ACS or acute splenic sequestration. In addition, acute infection with parvovirus B19 is associated with pain, splenic sequestration, ACS, glomerulonephritis, arthropathy, and stroke. Many patients with parvovirus-associated aplastic crisis are contagious, and infection precautions should be taken to avoid nosocomial spread of the infection and to avoid exposure of pregnant caregivers.

Splenic Sequestration

Acute splenic sequestration is a life-threatening complication occurring primarily in infants and young children with sickle cell anemia. The incidence of splenic sequestration has declined from an estimated 30% to 12.6% with early identification by newborn screening and improved parental education. Sequestration can occur as early as 5 wk of age but most often occurs in children between ages 6 mo and 2 yr. Patients with the SC and Sβ+ -thalassemia types of sickle cell disease can have acute splenic sequestration events throughout adolescence and adulthood.

Splenic sequestration is associated with rapid spleen enlargement causing left-sided abdominal pain and Hb decline of at least 2 g/dL from the patient's baseline. Sequestration may lead to signs of hypovolemia as a result of the trapping of blood in the spleen and profound anemia, with total Hb falling below 3 g/dL. A decrease in WBC and platelet count may also be present. Sequestration may be triggered by fever, bacteremia, or viral infections.

Treatment includes early intervention and maintenance of hemodynamic stability using isotonic fluid or blood transfusions. Careful blood transfusions with RBCs are recommended to treat both the sequestration and the resultant anemia. Blood transfusion aborts the RBC trapping in the spleen and allows release of the patient's blood cells that have become sequestered, often raising Hb above baseline values. A reasonable approach is to provide only 5 mL/kg of RBCs and/or a posttransfusion Hb target of 8 g/dL, keeping in mind that the goal of transfusion is to prevent hypovolemia. Blood transfusion that results in Hb levels >10 g/dL may put the patient at risk for hyperviscosity syndrome because blood may be released from the spleen after transfusion.

Repeated episodes of splenic sequestration are common, occurring in two thirds of patients. Most recurrent episodes develop within 6 mo of the previous episode. Prophylactic splenectomy performed after an acute episode has resolved is the only effective strategy for preventing future life-threatening episodes. Although blood transfusion therapy has been used with the goal of preventing subsequent episodes, evidence strongly suggests that this strategy does not reduce the risk of recurrent splenic sequestration compared to no transfusion therapy. However, a short course of regular red cell transfusions can be used until splenectomy is arranged. Children should be appropriately immunized with meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccines before surgery. Penicillin prophylaxis should be prescribed after splenectomy.

Hepatic and Gallbladder Involvement

See Chapters 387 and 393 .

Sickle Cell Pain

Dactylitis , referred to as hand-foot syndrome , is often the first manifestation of pain in infants and young children with sickle cell anemia, occurring in 50% of children by their 2nd yr of life (Fig. 489.1 ). Dactylitis often manifests with symmetric or unilateral swelling of the hands and/or feet. Unilateral dactylitis can be confused with osteomyelitis, and careful evaluation to distinguish the two is important because treatment differs significantly. Dactylitis requires palliation with pain medications, such as hydrocodone or oxycodone, whereas osteomyelitis requires at least 4-6 wk of IV antibiotics. Given the association between genotype and metabolism of codeine, a subgroup of children may not get pain relief from codeine. Therefore, feedback from the parents is needed to determine if therapy was successful in relieving pain.

The cardinal clinical feature of sickle cell disease is acute vasoocclusive pain . Acute sickle cell pain is characterized as unremitting discomfort that can occur in any part of the body but most often occurs in the chest, abdomen, or extremities. These painful episodes are often abrupt and cause disruption of daily life activities and significant stress for children and their caregivers. A patient with sickle cell anemia has approximately 1 painful episode per year that requires medical attention.

The exact etiology of pain is unknown, but the pathogenesis may be initiated when blood flow is disrupted in the microvasculature by sickled red blood cells and other cellular elements, resulting in tissue ischemia. Acute sickle cell pain may be precipitated by physical stress, infection, dehydration, hypoxia, local or systemic acidosis, exposure to cold, and swimming for prolonged periods. However, most pain episodes occur without an identifiable trigger. Successful treatment of these episodes requires education of both caregivers and patients regarding the recognition of symptoms and the optimal management strategy. Given the absence of any reliable objective laboratory or clinical parameter associated with pain, trust between the patient and the treating physician is paramount to successful clinical management. Specific therapy for pain varies greatly but generally includes the use of acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) early in the course of pain, followed by escalation to a combination analgesic regimen using a single-agent short-acting oral opioid, long-acting oral opioid, and continued nonopioid agent.

Some patients require treatment in an acute care setting for administration of IV morphine or derivatives of morphine. The primary goal of treatment in these settings is timely administration of analgesics to provide relief of pain. The incremental increase and decrease in the use of the medication to relieve pain roughly parallels the 8 phases associated with a chronology of pain and comfort in children (Table 489.3 ). When pain requires continued parenteral analgesic administration, hospitalization is required. The average hospital length of stay for children admitted in pain is 4.4 days. The NHLBI clinical guidelines for treating acute and chronic pain in children and adults with sickle cell disease are comprehensive and represent a starting point for treating pain.

Table 489.3

Phases of a Painful Episode in Patients With Sickle Cell Disease

| PHASE | DESCRIPTION AND COMFORT MEASURES |

|---|---|

| Data From Children | |

| I | Baseline |

| No pain and no comfort measures | |

| II | Prepain phase |

| No evidence of pain | |

| Child begins to display some prodromal signs and symptoms of VOE (yellow eyes, fatigue) | |

| No comfort measures used | |

| Caregivers encouraged child to increase fluids to prevent the pain event from occurring | |

| III | Pain starting point |

| Child complained of mild “ache-ish” pain in one specific area, which gradually or rapidly increased or “waxed” | |

| Mild analgesics (ibuprofen and acetaminophen) given | |

| Child maintained normal activities and continued to attend school | |

| Caregivers hoped to prevent an increase in pain intensity | |

| IV | Pain acceleration |

| Pain continued to escalate; intensity increased from mild to moderate; pain appeared in more areas of the body; child was kept home from school; decreased level of activity; differences in behaviors, appearance, and mood | |

| Stronger oral analgesics may be combined with rest, rubbing, heat, distraction, and psychological comfort | |

| V | Peak pain experience |

| Pain continued to escalate | |

| Some children were incapacitated and unable to obtain pain relief | |

| Pain described as “stabbing,” “drilling,” “pounding,” “banging,” “excruciating,” “unbearable,” or “throbbing” | |

| Caregivers sometimes decide to seek help from ED for stronger analgesics and protection from complications such as fever or respiratory distress | |

| Caregivers may be exhausted from caring for the child for several days with little or no rest | |

| All methods of comfort were used around the clock to reduce the pain and avoid going to the hospital | |

| Pain increased despite all efforts | |

| Decision is made to take the child to ED | |

| VI | Pain decrease starting point |

| Pain begins to resolve after the use of IV fluids and analgesics | |

| Analgesics sedate the child and allow the child to sleep for longer periods | |

| Pain described as “slowly decreasing” | |

| Pain is still sharp and throbbing | |

| VII | Steady pain decline |

| Pain decreased slowly or rapidly | |

| Child takes more interest in surroundings, roommates, and visitors | |

| Child is less irritable | |

| Level of activity increased—child may be taken to tub room for warm bath, may watch television, may play games with other children or hospital volunteers | |

| Mobility was improved | |

| Pain levels reported as “just a little” | |

| More animation in behaviors evident | |

| VIII | Pain resolution |

| Pain was at a tolerable level | |

| Child may be discharged from the hospital on mild oral analgesics; child is at or close to baseline conditions, with behavior, appearance, and mood more normal | |

| Caregiver and child attempt to regain, recapture, and catch up with life as it was before the pain event | |

| Data From Adults | |

| I | Evolving/infarctive phase |

| 3 days | |

| ↓ RBC deformability | |

| ↓ Hemoglobin | |

| ↑ % of dense RBCs | |

| ↑ RDW, ↑ HDW | |

| S/S: fear, anorexia, anxiety, ↑ pain | |

| II | Postinfarctive/inflammatory phase |

| 4-5 days | |

| ↓ Hemoglobin | |

| ↑ White blood cells (leukocytosis) | |

| ↑ Acute-phase reactants C-reactive protein | |

| ↑ Reticulocytes, ↑ LDH, ↑ CPK | |

| ↑ % dense RBCs | |

| ↑ RDW, ↑ HDW | |

| S/S: fever, severe steady pain, swelling, tenderness, joint stiffness, joint effusions | |

| III | Resolving/healing/recovery/postcrisis phase |

| ↑ RBC deformability | |

| Hemoglobin returns to precrisis level | |

| Retics return to precrisis levels | |

| ↓ % of dense RBCs | |

| ↓ RDW, ↓ HDW | |

| ↓ ISC | |

| Precursors to relapse that happens in phase III: ↑ platelets, ↑ acute-phase reactants (fibrinogen, α1 -acid glycoprotein, osmomucoid), ↑ viscosity, ↑ ESR | |

| ↑ Retics expressing the ↑ α4 β1 -integrin complex ICAM-1 | |

CPK, Creatinine phosphokinase; ED, emergency department; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HDW, hemoglobin distribution width; ICAM, intracellular adhesion molecule; ISC, irreversibly sickled cells; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; RBC, red blood cell; RDW, red cell distribution width; S/S, signs and symptoms; VOE, vasoocclusive episode.

Adapted from Jacob E: The pain experience of patients with sickle cell anemia, Pain Manage Nurs 2(3):74–83, 2001; with data from Ballas SK, Smith ED: Red blood cell changes during the evolution of the sickle cell painful crisis, Blood 79:2154–2163, 1992; and Beyer JE, Simmons L, Woods GM, Woods PM: A chronology of pain and comfort in children with sickle cell disease, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 153:913–920, 1999.

The only measure for degree of pain is the patient. Healthcare providers working with children in pain should use a consistent, validated pain scale (e.g., Wong-Baker FACES Scale) for assessing pain. Although pain scales have proved useful for some children, others require prenegotiated activities to determine when opioid therapy should be initiated and decreased. For example, sleeping through the night might be an indication for decreasing pain medication by 20% the following morning. The majority of painful episodes in patients with sickle cell disease are managed at home with comfort measures, such as heating blanket, relaxation techniques, massage, and oral pain medication.

Several myths have been propagated regarding the treatment of pain in sickle cell disease. The concept that painful episodes in children should be managed without opioids is without foundation and results in unwarranted suffering on the part of the patient. Blood transfusion therapy during an existing painful episode does not decrease the intensity or duration of the painful episode, because tissue necrosis occurs well before the ability to administer the transfusion. IV hydration does not relieve or prevent pain and is appropriate when the patient is dehydrated or unable to drink as a result of the severe pain. Opioid dependency in children with sickle cell disease is rare and should never be used as a reason to withhold pain medication. However, patients with multiple painful episodes requiring hospitalization within 1 yr or with pain episodes that require hospitalization for >7 days should be evaluated for comorbidities and environmental stressors that are contributing to the frequency or duration of pain. Children with chronic pain should be evaluated for other reasons associated with vasoocclusive pain episodes, including, but not limited to, presence of avascular necrosis, leg ulcers, and vertebral body compression fractures. A careful history is warranted to distinguish chronic pain that often is not relieved by opioids vs recurrent acute prolonged vasoocclusive pain episodes.

Skeletal pain (bone or bone marrow infarction) with or without fever must be differentiated from osteomyelitis . Both Salmonella spp. and S. aureus cause osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell disease, often involving the diaphysis of long bones (in contrast to children without sickle cell anemia, in whom osteomyelitis is in the metaphyseal region of the bone). Differentiating osteonecrosis from a vasoocclusive crisis and osteomyelitis is often difficult. Clinical signs and symptoms can be consistent with both osteonecrosis and vasoocclusive crises, as low-grade fever pain, swelling of the affected area, high WBC counts, and elevated C-reactive protein levels can be present in both. Blood cultures, when positive, are helpful. MRI may be useful for locating an area to obtain fluid for culture. MR findings suggestive of osteomyelitis include localized medullary fluid, sequestrum, and cortical defects. Ultimately, aspiration with or with or without biopsy and culture will be needed to differentiate the 2 processes (see Chapter 704 ).

Avascular Necrosis

Avascular necrosis (AVN ) occurs at a higher rate among children with sickle cell disease than in the general population and is a source of both acute and chronic pain. Most often the femoral head is affected. Unfortunately, AVN of the hip may cause limp and leg-length discrepancy. Other sites affected include the humeral head and mandible. Risk factors for AVN include HbSS disease with α-thalassemia trait, frequent vasoocclusive episodes, and elevated hematocrit (for patients with sickle cell anemia). Optimal treatment of AVN has not been determined, and individual management requires consultation with the disease-specific specialist, orthopedic surgeon, physical therapist, hematologist, and primary care physician. Initial management should include referral to a pediatric orthopedist and a physical therapist to address strategies to increase strength and decrease weight-bearing daily activities that may exacerbate the pain associated with AVN. Opioids are often used but usually can be tapered after the acute pain has subsided. Regular blood transfusion therapy has not been demonstrated as an effective therapy to abate the acute and chronic pain associated with AVN.

Priapism

Priapism, defined as an unwanted painful erection of the penis, affects males of all genotypes but most frequently affects males with sickle cell anemia. The mean age of first episode is 15 yr, although priapism has been reported in children as young as 3 yr. The actuarial probability of a patient experiencing priapism is approximately 90% by 20 yr of age.

Priapism occurs in 2 patterns: prolonged , lasting >4 hr, or stuttering , with brief episodes that resolve spontaneously but may occur in clusters and herald a prolonged event. Both types occur from early childhood to adulthood. Most episodes occur between 3 and 9 AM . Priapism in sickle cell disease represents a low-flow state caused by venous stasis from RBC sickling in the corpora cavernosa. Recurrent prolonged episodes of priapism are associated with erectile dysfunction (impotence).

The optimal treatment for acute priapism is unknown. Supportive therapy, such as a hot shower, short aerobic exercise, or pain medication, is often used by patients at home. A prolonged episode lasting >4 hr should be treated by aspiration of blood from the corpora cavernosa, followed by irrigation with dilute epinephrine to produce immediate and sustained detumescence. Urology consultation is required to initiate this procedure, with appropriate input from a hematologist. Simple blood transfusion with exchange transfusion has been proposed for the acute treatment of priapism, but limited evidence supports this strategy as the initial management. If no benefit is obtained from surgical management, transfusion therapy should be considered. However, detumescence may not occur for up to 24 hr (much longer than with urologic aspiration) after transfusion, and transfusion for priapism has been associated with acute neurologic events. Consultation with a hematologist and urologist will help identify therapies to prevent recurrences.

Neurologic Complications

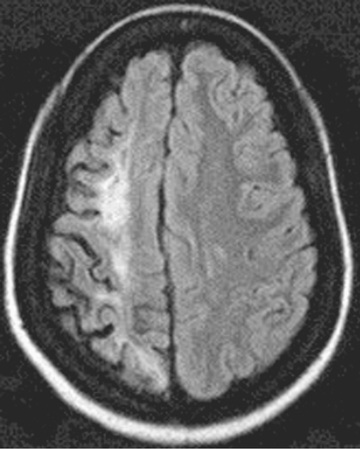

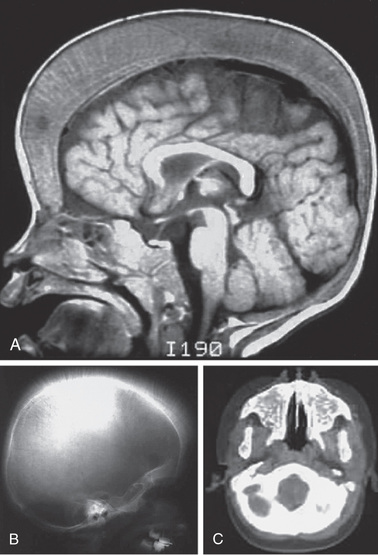

Neurologic complications associated with sickle cell disease are varied and complex, ranging from acute ischemic stroke with focal neurologic deficit to clinically silent abnormalities found on radiologic imaging. Before the development of transcranial Doppler ultrasonography to screen for stroke risk among children with sickle cell anemia, approximately 11% experienced an overt stroke and 20% a silent stroke before age 18 yr. A functional definition of overt stroke is the presence of a focal neurologic deficit lasting for >24 hr and/or abnormal neuroimaging of the brain indicating a cerebral infarct on T2-weighted MRI corresponding to the focal neurologic deficit (Figs. 489.2 and 489.3 ). A silent cerebral infarct lacks focal neurologic findings lasting >24 hr and is diagnosed by abnormal imaging on T2-weighted MRI. Children with other types of sickle cell disease, such as HbSC or HbSβ+ -thalassemia, develop overt or silent cerebral infarcts as well, but at a lower frequency than children with HbSS and HbSβ0 -thalassemia. Other neurologic complications include transient ischemic attacks, headaches that may or may not correlate to degree of anemia, seizures, cerebral venous thrombosis, and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) . Chiari I malformations can occur in older children with sickle cell disease. Fat embolism syndrome is a rapidly progressive, potentially fatal complication involving pain, respiratory distress, changes in mental status, and multiorgan system failure. When this syndrome is identified early, exchange transfusion therapy has improved patient survival in small case series.

For patients presenting with acute focal neurologic deficit, a prompt pediatric neurologic evaluation and consultation with a pediatric hematologist is recommended. In addition, oxygen administration to keep oxygen saturation (SO 2 ) >96% and simple blood transfusion within 1 hr of presentation, with a goal of increasing Hb to a maximum of 10 g/dL, is warranted. A timely simple blood transfusion is important because this is the most efficient strategy to dramatically increase oxygen content of the blood, if SO 2 is >96%. However, greatly exceeding this posttransfusion Hb limits oxygen delivery to the brain as a result of hyperviscosity by increasing the Hb significantly over the patient's baseline values. Subsequently, prompt treatment with an exchange transfusion should be considered, either manually or with automated erythrocytapheresis, to reduce the HbS percentage to at least <50% and ideally <30%. Exchange transfusion at the time of acute stroke is associated with a decreased risk of 2nd stroke compared to simple transfusion alone. CT of the head to exclude cerebral hemorrhage should be performed as soon as possible, and if available, MRI of the brain with diffusion-weighted imaging to distinguish between ischemic infarcts and PRES. MR venography is useful to evaluate the possibility of cerebral venous thrombosis , a rare but potential cause of focal neurologic deficit in children with sickle cell disease. MR angiography may identify evidence of cerebral vasculopathy; these images are not critical in the initial time management of a child with sickle cell disease presenting with a focal neurologic deficit.

The clinical presentation of PRES or central venous thrombosis can mimic a stroke but would require a different treatment course. For both PRES and cerebral venous thrombosis, the optimal management has not been defined in patients with sickle cell disease, resulting in the need for consultation with both a pediatric neurologist and a pediatric hematologist. The primary approach for prevention of recurrent overt stroke is blood transfusion therapy aimed at keeping the maximum HbS concentration <30%. Despite regular blood transfusion therapy, approximately 20% of patients will have a 2nd stroke and 30% of this group will have a 3rd stroke.

Transcranial Doppler Ultrasonography

Primary prevention of overt stroke can be accomplished using screening transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (TCD) assessment of the blood velocity in the terminal portion of the internal carotid and the proximal portion of the middle cerebral artery. Children with sickle cell anemia with an elevated time-averaged mean maximum (TAMM) blood flow velocity >200 cm/sec are at increased risk for a cerebrovascular event. A TAMM measurement of <200 but ≥180 cm/sec represents a conditional threshold. A repeat measurement is suggested within a few months because of the high rate of conversion to a TCD velocity >200 cm/sec in this group of patients. However a single value ≥220 cm/sec is concerning and does not require repeating before recommending an intervention.

Two distinct methods of measuring TCD velocity are a nonimaging technique and an imaging technique. The nonimaging technique was the method used in the stroke prevention trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, whereas most pediatric radiologists in practice use the imaging technique. When compared to each other, the imaging technique produces values that are 10–15% below those of the nonimaging technique. The imaging technique uses the time-averaged mean of the maximum velocity (TAMX), and this measure is believed to be equivalent to the nonimaging calculation of TAMM. A downward adjustment for the transfusion threshold is appropriate for centers using the imaging method to assess TCD velocity. The magnitude of the transfusion threshold in the imaging technique has not been settled, but a transfusion threshold of a TAMX of 185 cm/sec and a conditional threshold of TAMX of 165 cm/sec seem reasonable. Alternatively, some experts recommend using the same thresholds regardless of technique.

Children with TCD values above defined thresholds should begin chronic blood transfusion therapy to maintain HbS levels <30% to decrease the risk of 1st stroke. This strategy results in an 85% reduction in the rate of overt strokes. Once transfusion therapy is initiated, a subset of patients at low risk for the development of increased TCD values, such as those without MRI-confirmed cerebral vasculopathy, may be able to transition from chronic transfusions to long-term hydroxyurea therapy. Acute stroke risk is decreased when hydroxyurea use and chronic transfusions overlap until a robust therapeutic response to hydroxyurea is achieved.

Pulmonary Complications

Lung disease in children with sickle cell disease is the 2nd most common reason for hospital admission and is associated with significant mortality. Acute chest syndrome refers to a life-threatening pulmonary complication of sickle cell disease defined as a new radiodensity on chest radiography plus any 2 of the following: fever, respiratory distress, hypoxia, cough, and chest pain (Fig. 489.4 ). Even in the absence of respiratory symptoms, very young children with fever should receive a chest radiograph to identify evolving ACS, because clinical examination alone is insufficient to identify patients with a new radiographic density. Early detection of ACS may alter clinical management. The radiographic findings in ACS are variable but may include single-lobe involvement, predominantly left lower lobe; multiple lobes, most often both lower lobes; and pleural effusions, either unilateral or bilateral. ACS may progress rapidly from a simple infiltrate to extensive infiltrates and a pleural effusion. Therefore, continued pulse oximetry and frequent clinical exams are required, and repeat chest x-ray films may be indicated for progressive hypoxia, dyspnea, tachypnea, and other signs of respiratory distress.

Most patients with ACS do not have a single identifiable cause. Infection is the most well-known etiology, yet only 30% of ACS episodes will have positive sputum or bronchoalveolar culture, and the most common bacterial pathogens are S. pneumoniae , Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia spp. The most frequent event preceding ACS is a painful episode requiring systemic opioid treatment. Fat emboli have also been implicated as a cause of ACS, arising from infarcted bone marrow, and can be life threatening if large amounts are released to the lungs. Fat emboli can be difficult to diagnose but should be considered in any patient with sickle cell disease presenting with rapid onset of respiratory distress and altered mental status changes. Petechial rash may also occur, but may be difficult to detect if not carefully sought.

Given that the causes of ACS are varied, recommended management is also multimodal (Table 489.4 ). The type of opioid, with morphine being more likely to cause ACS than nalbuphine hydrochloride, is associated with an increase in the risk of ACS in part because of sedation and hypoventilation. However, under no circumstance should opioid administration be limited to prevent ACS; rather, other measures must be taken to prevent ACS from developing. In patients with chest pain, regular use of an incentive spirometer at 10-12 breaths every 2 hr can significantly reduce the frequency of subsequent ACS episodes. Because of the clinical overlap between pneumonia and ACS, all episodes should be treated promptly with antimicrobial therapy, including at least a macrolide and possibly a third-generation cephalosporin. A previous diagnosis of asthma or wheezing with ACS should prompt treatment following standard of care for an asthma exacerbation with bronchodilators. The diagnosis of ACS does not negate the recommended management of a patient with asthma exacerbation. Oxygen should be administered for patients who demonstrate hypoxia. Blood transfusion therapy using either simple or exchange (manual or automated) transfusion is the only method to abort a rapidly progressing ACS episode. The decision when to give blood and whether the transfusion should be a simple or exchange transfusion is less clearly defined. Usually, blood transfusions are given when at least 1 of the following clinical features are present: decreasing SO 2 , increasing work of breathing, rapidly changing respiratory effort either with or without a worsening chest radiograph, a dropping Hb of 2 g/dL below the patient's baseline, or previous history of severe ACS requiring admission to the intensive care unit.

Pulmonary hypertension has been identified as a major risk factor for death in adults with sickle cell anemia. The natural history of pulmonary hypertension in children with sickle cell anemia is unknown. Optimal strategies for screening at risk patients have not been identified (echocardiogram results are not supported by right-sided heart catheterization results demonstrating elevated pulmonary artery pressures), and the best diagnostic methodology carries significant risk of harm. Attempts to identify targeted therapeutic interventions to alter the natural history of pulmonary hypertension in adults have been unsuccessful.

Renal Disease and Enuresis

Renal disease among patients with sickle cell disease is a major comorbid condition that can lead to premature death. Seven sickle cell disease nephropathies have been identified: gross hematuria, papillary necrosis, nephrotic syndrome, renal infarction, hyposthenuria, pyelonephritis, and renal medullary carcinoma. The presentation of these entities is varied but may include hematuria, proteinuria, renal insufficiency, concentrating defects, or hypertension.

The common presence of nocturnal enuresis occurring in children with sickle cell disease is not well defined but is troublesome for affected children and their parents. The overall prevalence of enuresis was 33% in the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease, with the highest prevalence (42%) among children 6-8 yr old. Furthermore, enuresis may still occur in approximately 9% of older adolescents. Patients with sickle cell disease and nocturnal enuresis should have a systematic evaluation for recurrent urinary tract infections, kidney function, and possibly obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Unfortunately, most children with nocturnal enuresis do not have an etiology, and targeted therapeutic interventions have been of limited success. However, referrals to pediatric urologists should be considered.

Cognitive and Psychological Complications

Good health maintenance must include routine psychological and social assessment. Ongoing evaluation of the family unit and identification of the resources available to cope with a chronic illness are critical for optimal management. Children and adolescents with sickle cell disease have decreased quality of life, as measured on standardized assessments, compared to their siblings and children with other chronic diseases. Furthermore, children with sickle cell disease are at great risk for academic failure and have a 20% high school graduation rate, possibly because, among other reasons, approximately one third of children with sickle cell anemia have had a cerebral infarct, either silent or an overt stroke. Children with cerebral infarcts require ongoing cognitive and school performance assessment so that education resources can be focused to optimize educational attainment. Participation in relevant support groups and group activities, such as camps for children with sickle cell disease, may be of direct benefit by improving self-esteem and establishing peer relationships.

Other Complications

In addition to the previous organ dysfunctions, patients with sickle cell disease can have other significant complications. These complications include, but are not limited to, sickle cell retinopathy, delayed onset of puberty, and leg ulcers. Optimal treatment for each of these entities has not been determined, and individual management requires consultation with the hematologist and primary care physician.

Therapeutic Considerations

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea, a myelosuppressive agent, is a well-established drug proven effective in reducing the frequency of acute pain episodes. In adults with sickle cell anemia, hydroxyurea decreases the rate of hospitalization for painful episodes by 50% and the rate of ACS and blood transfusion by almost 50%. In addition, adults taking hydroxyurea have shorter hospital stay and require less analgesic medication during hospitalization. In children with sickle cell anemia, a safety feasibility trial demonstrated that hydroxyurea was safe and well tolerated in children >5 yr of age. No clinical adverse events were identified in this study; the primary toxicities were limited to myelosuppression that reversed on cessation of the drug. In addition, infants treated with hydroxyurea experienced fewer episodes of pain, dactylitis, and ACS; were hospitalized less frequently; and less often required a blood transfusion. Despite taking a myelosuppressive agent, the infants treated with hydroxyurea did not experience increased rates of bacteremia or serious infection. Current recommendations are that all children with sickle cell anemia should be offered hydroxyurea beginning at 9 mo of age.

Hydroxyurea may be indicated for other sickle cell–related complications, especially in patients who are unable to tolerate other treatments. For patients who either will not or cannot continue blood transfusion therapy to prevent recurrent stroke, hydroxyurea therapy may be a reasonable alternative. The trial assessing the efficacy of hydroxyurea as an alternative to transfusions to prevent a 2nd stroke was terminated early after the data safety and monitoring found an increased stroke rate in the hydroxyurea arm compared to the transfusion arm (0 vs 7 [10%]). Hydroxyurea alone is inferior to transfusion therapy for secondary stroke prevention in patients who do not have contraindications to ongoing transfusions.

The long-term toxicity associated with initiating hydroxyurea in very young children has not yet been established. However, all evidence to date suggests that the benefits far outweigh the risks. For these reasons, very young children starting hydroxyurea require well-informed parents and medical care by pediatric hematologists, or at least co-management by a physician with expertise in immunosuppressive medications. The typical starting dose of hydroxyurea is 15-20 mg/kg once daily, with an incremental dosage increase every 8 wk of 5 mg/kg, and if no toxicities occur, up to a maximum of 35 mg/kg per dose. The infant hydroxyurea study found young children could safely be started at 20 mg/kg/day without increased toxicity. Achievement of the therapeutic effect of hydroxyurea can require several months, and for this reason, initiating hydroxyurea to address short-term symptom relief is not optimal. We prefer to introduce the concept to parents within the 1st yr of life, preferably by 9 mo; provide literature that describes both the pros and cons of starting hydroxyurea in children with severe symptoms of sickle cell disease; and educate parents on starting hydroxyurea in asymptomatic children as a preventive therapy for repetitive pain and ACS events. Other effects of hydroxyurea that may vary include an increase in the total Hb level and a decrease in the TCD velocity.

The FDA has approved oral L-glutamine, used as an add on to hydroxyurea, for patients ≥5 yr. L-glutamine has been shown to reduce hospitalizations and sickle cell crisis.

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

The only cure for sickle cell anemia is transplantation with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched hematopoietic stem cells from a sibling or unrelated donor. Clinical trials are underway to determine whether gene therapy or gene editing therapy is a safe, effective, long-term cure for those with sickle cell anemia. The most common indications for transplant are recurrent ACS, stroke, and abnormal TCD. Sibling-matched stem cell transplantation has a lower risk for graft-versus-host disease than unrelated donors. Surveys suggest that younger children may have lower morbidity and mortality. However, few children have suitable sibling donors. Stem cell transplantation using an unrelated but well-matched donor remains a focus of clinical research. The decision to consider unrelated transplantation should involve appropriate consultation and counseling from physicians with expertise in sickle cell transplantation.

Stem cell transplantation for children with sickle cell disease who have a genetically matched sibling and few complications is not routinely performed. The use of hydroxyurea has dramatically decreased the disease burden for the patient and family, with far fewer hospitalizations for pain or ACS episodes and less use of blood transfusions. Furthermore, the field of stem cell transplantation is progressing so rapidly that nonsibling donor, including haploidentical, transplantation and gene therapy studies are underway. Transplant-related complications caused by conditioning regimens may be decreased by using low-intensity, nonmyeloablative HLA-matched sibling, allogenic stem cell transplantation.

Red Blood Cell Transfusions

RBC transfusions are used frequently both in the treatment of acute complications and to prevent acute or recurrent complications. Typically, short-term transfusions are used to prevent progression of acute complications such as ACS, aplastic crisis, splenic sequestration, and acute stroke, as well as to prevent surgery-related ACS. RBC transfusions are not recommended for uncomplicated acute pain events. Select RBC volumes judiciously to avoid high posttransfusion Hb levels and hyperviscosity. Long-term or chronic transfusion therapy is used to prevent 1st stroke in patients with abnormal TCD or MRI findings (silent stroke), recurrent stroke, or recurrent ACS. Patients with sickle cell disease are at increased risk of developing alloantibodies to less common RBC surface antigens after receiving even a single transfusion. In addition to standard cross matching for major blood group antigens (A, B, O, RhD), more extended matching should be performed to identify donor units that are C-, E-, and Kell-antigen matched. Some centers have begun to perform full RBC antigen phenotyping or genotyping for patients receiving chronic blood transfusions, in order to have the red cell units least likely to result in alloimmunization available for these patients.

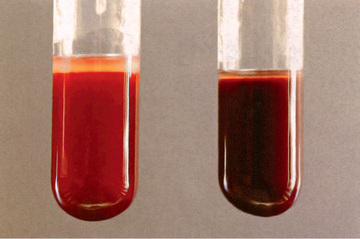

Three methods of blood transfusion therapy are used in the management of acute and chronic complications associated with sickle cell disease: automated erythrocytapheresis, manual exchange transfusion (phlebotomy of a set amount of patient's blood followed by rapid administration of donated packed RBCs), and simple transfusion. The decision on which method to use depends on the patient's pretransfusion Hb level, the clinical indication, RBC alloimmunization, and transfusional iron overload. Automated erythrocytapheresis is the preferred method for patients requiring chronic blood transfusion therapy because there is a minimum net iron balance after the procedure, followed by manual exchange transfusion. However, this method requires technical expertise, special machines, and good patient venous access. Manual exchange is more accessible. However, both methods may expose the patient to more red cell units and possible alloimmunization. Simple transfusion therapy may lower donor exposure but may result in higher net iron burden when compared to erythrocytapheresis or exchange transfusion.

Preparation for surgery for children with sickle cell disease requires a coordinated effort from the hematologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and primary care provider. Historically, ACS was associated with general anesthesia in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood transfusion prior to surgery for children with sickle cell disease is recommended to raise Hb level preoperatively to no more than 10 g/dL, to avoid ACS development. Because of better general perioperative care and the use of long-term therapies such as hydroxyurea and chronic transfusions, the decision to transfuse before general anesthesia should be made in conjunction with the medical team who provides sickle cell disease–related care for the patient. When preparing a child with sickle cell disease for surgery with a simple blood transfusion, caution must be used not to elevate Hb level beyond 10 g/dL because of the risk of hyperviscosity syndrome. For children with milder forms of sickle cell disease, such as HbSC or HbSβ-thalassemia, a decision must be made on a case-by-case basis as to whether an exchange transfusion is warranted, because a simple transfusion may raise the hemoglobin to an unacceptable level.

Iron Overload

The primary toxic effect of blood transfusion therapy relates to excessive iron stores or iron overload, which can result in organ damage and premature death. Excessive iron stores develop after 100 mL/kg of red cell transfusion, or about 10 transfusions. The assessment of iron overload in children receiving regular blood transfusions is difficult. The most common and least invasive method of estimating total body iron involves serum ferritin levels. Ferritin measurements have significant limitations in their ability to estimate iron stores for several reasons, including, but not limited to, elevation during acute inflammation and poor correlation with excessive iron in specific organs after 2 yr of regular blood transfusion therapy. MRI of the liver has proved to the most effective approach for assessment of iron stores. The imaging strategy is more accurate than serum ferritin in measuring heart and liver iron content. MRI T2* and MRI R2 and R2* sequences are used to estimate iron levels in the heart and liver. The standard for iron assessment previously was liver biopsy, which is an invasive procedure exposing children to the risk of general anesthesia, bleeding, and pain. Liver biopsy alone does not accurately estimate total body iron because iron deposition in the liver is not homogeneous and varies among the affected organs; that is, the amount of iron found in the liver is not equivalent to cardiac tissues. The major advantage of a liver biopsy is that histologic assessment of the parenchyma can be ascertained along with appropriate staging of suspected pathology, particularly cirrhosis.

The primary treatment of transfusion-related iron overload requires iron chelation using medical therapy. In the United States, 3 chelating agents are approved for use in transfusional iron overload. Deferoxamine is administered subcutaneously 5 of 7 nights/wk for 10 hr a night. Deferasirox is taken by mouth daily, and deferiprone is available in tablets taken orally twice a day. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved deferasirox, the newest oral chelator, in 2005 for use in patients age ≥2 yr. A pill formulation of deferasirox is available that does not require mixing before oral administration. Deferiprone is an older oral chelator that has been widely used outside the United States for many years and was approved by the FDA in 2011, but requires weekly CBC monitoring because of neutropenia risk throughout therapy. Transfusion-related excessive iron stores in children with sickle cell disease should be managed by a physician with expertise in chelation therapy because of the risk of significant toxicity from available chelation therapies.

Other Sickle Cell Syndromes

The most common sickle cell syndromes besides HbSS are HbSC, HbSβ0 -thalassemia, and HbSβ+ -thalassemia. The other syndromes—HbSD, HbSOArab , HbSHPFH, HbSE, and other variants—are much less common. Patients with HbSβ0 -thalassemia have a clinical phenotype similar to those with HbSS. In the red cells of patients with HbSC, crystals of HbC interact with membrane ion transport, dehydrating RBCs and inducing sickling. Children who have HbSC disease can experience the same symptoms and complications as those with severe HbSS disease, but less frequently. Children with HbSC have increased incidence of retinopathy, chronic hypersplenism, and acute splenic sequestration over the life span. The natural history of the other sickle cell syndromes is variable and difficult to predict because of the lack of systematic evaluation.

There is no validated model that can predict the clinical course of an individual with sickle cell disease. A patient with HbSC can have a more severe clinical course than a patient with HbSS. Management of end-organ dysfunction in children with sickle cell syndromes requires the same general principles as managing patients with sickle cell anemia; however, each situation should be managed on a case-by-case basis and requires consultation with a pediatric hematologist.

Anticipatory Guidance

Children with sickle cell disease should receive general health maintenance as recommended for all children, with special attention to disease-specific guidance and infection prevention education. In addition to counseling regarding adherence to penicillin and a vaccination schedule, patients, parents and caregivers should be instructed to seek immediate medical attention for all febrile illness. In addition, early detection of acute splenic sequestration has been shown to decrease mortality. Therefore, parents and caregivers should be educated early and repeatedly about the importance of daily penicillin administration and correct palpation of the spleen.

Prophylactic Penicillin

Children with sickle cell anemia should receive prophylactic oral penicillin VK until at least 5 yr of age (125 mg twice daily up to age 3 yr, then 250 mg twice daily thereafter). No established guidelines exist for penicillin prophylaxis beyond 5 yr of age; some clinicians continue penicillin prophylaxis, and others recommend discontinuation. Continuation of penicillin prophylaxis should be continued beyond 5 yr in children with a history of pneumococcal infection because of the increased risk of a recurrent infection. An alternative for children who are allergic to penicillin is erythromycin ethylsuccinate.

Immunizations

In addition to penicillin prophylaxis, routine childhood immunizations, as well as the annual administration of influenza vaccine, are highly recommended. Children with sickle cell disease develop functional asplenia and also require immunizations to protect against encapsulated organisms, including additional pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccinations. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides vaccination guidelines at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html .

Spleen Palpation

Splenomegaly is a common complication of sickle cell disease, and splenic sequestration can be life threatening. Parents and primary caregivers should be taught how to palpate the spleen to determine if the spleen is enlarging starting at the 1st visit, with reinforcement at subsequent visits. Parents should also demonstrate spleen palpation to the provider.

Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound

Primary stroke prevention using TCD has resulted in a decrease in the prevalence of overt stroke among children with sickle cell anemia. Children with HbSS or HbSβ0 -thalassemia should be screened annually with TCD starting at age 2 yr. TCD is best performed when the child is quietly awake and in his or her usual state of health. TCD measurements may be falsely elevated or decreased in the settings of acute anemia, sedation, pain, fever, or immediately after blood transfusions. Screening should occur annually from age 2-16 yr. Abnormal values should be repeated within 2-4 wk to identify patients at greatest risk of overt stroke. Conditional values should be repeated within 3 mo, and normal values should be repeated annually. Routine neuroimaging with MRI in asymptomatic patients requires consultation with a pediatric hematologist or neurologist with expertise in sickle cell disease.

Hydroxyurea

Recommendations provided in the 2014 NHLBI Expert Panel Report include offering hydroxyurea therapy to all children with sickle cell anemia starting at 9 mo of age regardless of clinical symptoms. Monitoring children receiving hydroxyurea is labor intensive. Hydroxyurea is a chemotherapeutic agent, and patients receiving this agent require the same level of nursing and physician oversight as any child with cancer receiving chemotherapy. The parents must be educated about the consequences of therapy, and when ill, children should be promptly evaluated. Starting doses should be approximately 20 mg/kg/day. CBC with differential and reticulocyte count should be checked within 4 wk after initiation of therapy or any dose change to monitor for hematologic toxicity, then every 8-12 wk. Dose escalation should be based on clinical and laboratory parameters. If necessary, dose increases should be in 5 mg/kg/day increments to a maximum of 35 mg/kg/day.

While receiving hydroxyurea, steady-state absolute neutrophil count should be approximately 2,000/µL or higher and platelet count should be 80,000/µL or higher. Younger children may tolerate lower absolute neutrophil counts while receiving hydroxyurea. Holding hydroxyurea and adjusting to lower doses may be required for neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Hydroxyurea is a pregnancy class D medication, and adolescents should be counseled regarding methods to prevent pregnancy while taking this medication. Close monitoring of the patient requires a commitment by the parents and the patient as well as diligence by a physician to identify toxicity early. Information is scarce regarding the impact of hydroxyurea on fertility, although hydroxyurea has been shown to further reduce sperm count in males with sickle cell disease in several case reports, suggesting that this effect may be reversible once hydroxyurea is discontinued.

Red Cell Transfusion Therapy

At the initiation of blood transfusion therapy, children with sickle cell disease should have testing to identify the presence of alloantibodies and RBC phenotyping or genotyping, which is performed to identify the best matched blood. Red cell units selected should be extended antigen-matched for C, E, and K, when feasible. Goals of transfusion for acute events should be established before initiating therapy, including target posttransfusion Hb level and HbS percentage, or both. For children receiving chronic transfusion therapy, pretransfusion HbS goals should be defined; the most common goal is <30%. Posttransfusion Hb values should be targeted to avoid hyperviscosity. Children, parents, and caregivers should be educated about the symptoms of delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions. Any child with sickle cell disease with a recent history of red cell transfusion who presents with pain, dark urine, increased scleral icterus, or symptoms of worsening anemia should be screened for a delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction after consultation with the blood bank. Children meeting criteria for chronic transfusion therapy should receive annual evaluation for transfusion-transmitted infections, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. After receiving 100 mL/kg RBC transfusions, regular assessments of iron overload should begin, usually including measurements of serum ferritin and assessments for hepatic and cardiac iron every 1-2 yr. For children requiring chelation therapy, an audiogram should be performed annually and monitoring of liver function and pituitary function performed regularly because of iron deposition.

Pulmonary and Asthma Screening

Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease are common and life threatening. Asthma is common in children with sickle cell disease, and thus evaluation for asthma symptoms and asthma risk factors should be performed routinely, particularly given the high morbidity and mortality. All children should receive annual screening for signs and symptoms of lower airway disease, such as nighttime cough and exercise-induced cough. In children with symptoms consistent with lower airway disease, consultation with an asthma specialist should be considered. Pulse oximetry readings should be performed during well visits to identify children with abnormally low daytime oxygen saturation. For children with snoring, daytime somnolence, and symptoms associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), sleep studies should be performed as necessary.

Retinopathy

Effective therapy is available for retinopathy associated with sickle cell disease. Although all patients are at risk for development of retinopathy, those with SC are at very high risk. Patients should receive annual screening by an ophthalmologist to identify vascular changes that would benefit from laser therapy. Although changes may occur earlier, children with sickle cell disease should begin annual screening no later than age 10 yr.

Renal Disease

Sickle cell–associated renal disease starts in infancy and may not become clinically evident until adulthood. Chronic kidney disease is common in adults with sickle cell disease, with high morbidity and mortality. Screening protocols for early signs of sickle nephropathy in children have not been adopted due to lack of data. However, when creatinine elevation, microalbuminuria, or macroalbuminuria is detected, a nephrologist should be consulted to determine next steps for further evaluation and possible treatment. The age to begin screening for proteinuria has not been defined, but some experts recommend screening annually after at least 10 yr, if not sooner. If proteinuria is detected, urine studies should be repeated with an early-morning urine collection; if the protein remains elevated, the patient should be referred to a pediatric nephrologist. Males with sickle cell disease should also receive counseling regarding the diagnosis and treatment of priapism. Because of the high frequency of enuresis beyond early childhood, approximately 9% between 18 and 20 yr of age, parents and caregivers should be educated about the prolonged nature of enuresis in this disease. OSAS is associated with an increased prevalence of enuresis in sickle cell disease. Unfortunately, no evidence-based therapies have been developed to treat enuresis in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. In children with enuresis who have symptoms and clinical features of OSAS, referral to specialists for evaluation is recommended.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is a screening tool to identify individuals with sickle cell disease who have pulmonary artery hypertension. No evidence currently shows that children with sickle cell disease and elevated tricuspid jet velocity >2.5 cm/sec have an increased rate of mortality. Studies in adults with sickle cell disease have found that echocardiography is insensitive at identifying individuals truly at risk for pulmonary hypertension, although an elevated tricuspid velocity measurement may still be a risk factor for premature death in adults with sickle cell disease. The current recommendation is to refer those with severe cardiopulmonary symptoms from associated pulmonary artery hypertension to a pediatric cardiologist for a more formal evaluation.

Additional Screening

Patients with sickle cell disease are at increased risk for behavioral health issues, including anxiety and depression. Screening should be performed at routine and acute visits. Avascular necrosis of the hips and shoulders is increased in patients with sickle cell disease and may be identified early on routine physical exam. Plain radiographs may not detect early disease; thus, when AVN is suspected and plain films are normal, MRI should be obtained. When AVN is confirmed, patients should be referred promptly to orthopedics and physical therapy.

Bibliography

Abboud MR, Yim E, Musallam KM, et al. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions increases the risk of silent brain infarction in children with sickle cell disease: data from STOP II. Blood . 2011;118(4):894–898.

Ataga KI, Kutlar A, Kanter J, et al. Crizanlizumab for the prevention of pain crises in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med . 2017;376(5):429–438.

Ballas SK, Bauserman RL, McCarthy WF, et al. Hydroxyurea and acute painful crises in sickle cell anemia: effects on hospital length of stay and opioid utilization during hospitalization, outpatient acute care contacts, and at home. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2010;40(6):870–882.

Baskin MN, Goh XL, Heeney MM, et al. Bacteremia risk and outpatient management of febrile patients with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics . 2013;131(6):1035–1041.

Belmont AP, Nossair F, Brambilla D, et al. Safety of deep sedation in young children with sickle cell disease: a retrospective cohort study. J Pediatr . 2015;166:1226–1232.

Berger E, Saunders N, Wang L, et al. Sickle cell disease in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2009;163:251255.

Beyer JE, Simmons LE, Woods GM, et al. A chronology of pain and comfort in children with sickle cell disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 1999;153(9):913–920.

Bolanos-Meade J, Fuchs EJ, Luznik L, et al. HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide expands the donor pool for patients with sickle cell disease. Blood . 2012;120(22):4285–4291.

Brandow AM, Zappia KJ, Stucky CL. Sickle cell disease: a natural model of acute and chronic pain. Pain . 2017;158:S79–S84.

Brousse V, Elie C, Benkerrou M, et al. Acute splenic sequestration crisis in sickle cell disease: cohort study of 190 paediatric patients. Br J Haematol . 2012;156(5):643–648.

Brousseau DC, McCarver DG, Drendel AL, et al. The effect of CYP2d6 polymorphisms on the response to pain treatment for pediatric sickle cell pain crisis. J Pediatr . 2007;150(6):623–626.

Brousseau DC, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, et al. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the United States: national and state estimates. Am J Hematol . 2010;85(1):77–78.

Buchanan ID, Woodward M, Reed GW. Opioid selection during sickle cell pain crisis and its impact on the development of acute chest syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2005;45(5):716–724.

Burnett MW, Bass JW, Cook BA. Etiology of osteomyelitis complicating sickle cell disease. Pediatrics . 1998;101(2):296–297.

Dallas MH, Triplett B, Shook DR, et al. Long-term outcome and evaluation of organ function in pediatric patients undergoing haploidentical and matched related hematopoietic cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant . 2013;19(5):820–830.

Davis BA, Allard S, Qureshi A, et al. British committee for standards in haematology: guidelines on red cell transfusion in sickle cell disease. Part I. Principles and laboratory aspects. Br J Haematol . 2017;176:179–191.

DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry MJ, et al. Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med . 2014;371:699–710.

DeBaun MR, Sarnaik SA, Rodeghier MJ, et al. Associated risk factors for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia: low baseline hemoglobin, gender and relative high systolic blood pressure. Blood . 2012;119:3684–3690.

DeBaun MR, Struck RC. The intersection between asthma and acute chest syndrome in children with sickle-cell anaemia. Lancet . 2016;387:2545–2552.

DeBaun MR, Telfair J. Transition and sickle cell disease. Pediatrics . 2012;130:926–935.

Dever DP, Bal RO, Reinisch A, et al. CRISPR/cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature . 2016;539(7629):384–389.

Dowling MM, Quinn CT, Plumb P, et al. Acute silent cerebral ischemia and infarction during acute anemia in children with and without sickle cell disease. Blood . 2012;120:3891–3897.

Ellison AM, Ota KV, McGowan KL, et al. Pneumococcal bacteremia in a vaccinated pediatric sickle cell disease population. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2012;5:534–536.

Field JJ, Austin PF, An P, et al. Enuresis is a common and persistent problem among children and young adults with sickle cell anemia. Urology . 2008;72:81–84.

Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle cell disease: old discoveries, new concepts, and future promise. J Clin Invest . 2007;117:850–858.

Gillis VL, Senthinathan A, Dzingina M, et al. Management of an acute painful sickle cell episode in hospital: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ . 2012;344:e4063.

Gladwin MT. Cardiovascular complications and risk of death in sickle-cell disease. Lancet . 2016;387:2565–2572.

Gluckman E, Cappelli B, Bernaudin F, et al. The pediatric working party of the European society for blood and marrow transplantation, and the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Sickle cell disease: an international survey of results of HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood . 2017;129:1548–1556.

Halasa NB, Shankar SM, Talbot TR, et al. Incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among individuals with sickle cell disease before and after the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:1428–1433.

Hines PC, McKnight TP, Seto W, et al. Central nervous system events in children with sickle cell disease presenting acutely with headache. J Pediatr . 2011;159:472–478.

Hsieh MM, Fithugh CD, Weitzel P, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe sickle cell phenotype. JAMA . 2014;312:48–56.

Hoppe C. Newborn screening for hemoglobin disorders. Hemoglobin . 2011;35(5/6):556–564.

Huang X, Wang Y, Yan W, et al. Production of gene-corrected adult beta globin protein in human erythrocytes differentiated from patient IPSCs after genome editing of the sickle point mutation. Stem Cells . 2015;33(5):1470–1479.

Hulbert ML, Scothorn DJ, Panepinto JA, et al. Exchange blood transfusion compared with simple transfusion for first overt stroke is associated with a lower risk of subsequent stroke: a retrospective cohort study of 137 children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr . 2006;149(5):710–712.

Jain R, Sawhney S, Rizvi SG. Acute bone crises in sickle cell disease: the T1 fat-saturated sequence in differentiation of acute bone infarcts from acute osteomyelitis. Clin Radiol . 2008;63:59–70.

Jordan LC, Casella JF, DeBaun MR. Prospects for primary stroke prevention in children with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol . 2012;157:14–25.

Kassim AA, Sharma D. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for sickle cell disease: the changing landscape. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther . 2017;10(4):259–266.

Kato GJ, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest . 2017;127:750–760.

King LGC, Bortolusso-Ali S, Cunningham CA, Reid MEG. Impact of a comprehensive sickle cell center on early childhood mortality in a developing country: the jamaican experience. J Pediatr . 2015;167:702–705.

Knight-Madden JM, Hambleton JR. Inhaled bronchodilators for acute chest syndrome in people with sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2012;(7) [CD003733].

Kuhn JP, Slovis TL, Haller JO. ed 11. Mosby: St Louis; 2008:1087. Caffey's pediatric diagnostic imaging . vol 2.

Kwiatkowski JL, Cohen AR, Garro J, et al. Transfusional iron overload in children with sickle cell anemia on chronic transfusion therapy for secondary stroke prevention. Am J Hematol . 2012;87:221–223.

Lehmann GC, Bell TR, Kirkham FJ, et al. Enuresis associated with sleep disordered breathing in children with sickle cell anemia. J Urol . 2012;188(4 Suppl):1572–1576.

Lettre G, Bauer DE. Feral haemoglobin in sickle-cell disease: from genetic epidemiology to new therapeutic strategies. Lancet . 2016;387:2554–2562.

Madigan C, Malik P. Pathophysiology and therapy for haemoglobinopathies. Part I. Sickle cell disease. Expert Rev Mol Med . 2006;8:1–23.

Mahadeo KM, Oyeku S, Taragin B, et al. Increased prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in children and adolescents with sickle-cell disease. Am J Hematol . 2011;86(9):806–808.

Mehari A, Gladwin MT, Tian X, et al. Mortality in adults with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. JAMA . 2012;307:1254–1256.

Meier ER, Miller JL. Sickle cell disease in children. Drugs . 2012;72:895–906.

Merritt AL, Haiman C, Henderson SO. Myth: blood transfusion is effective for sickle cell anemia-associated priapism. CJEM . 2006;8:119–122.

Miller AC, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012;185:1154–1165.

Miller ST, Kim HY, Weiner D, et al. Inpatient management of sickle cell pain: a “snapshot” of current practice. Am J Hematol . 2012;87:333–336.

Naik RP, Derebail VK, Grams ME, et al. Association of sickle cell trait with chronic kidney disease and albuminuria in African Americans. JAMA . 2014;312:2115–2124.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. 2014 Expert Panel report on the evidence-based management of sickle cell disease . www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/sickle-cell-disease-report.pdf .

Nicholson GT, Hsu DT, Colan SD, et al. Coronary artery dilation in sickle cell disease. J Pediatr . 2011;159:789–794.

Niihara Y, Miller ST, Kanter J, et al. A phase 3 trial of L-glutamine in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med . 2018;379(3):226–235.