Neuroblastoma

Douglas J. Harrison, Joann L. Ater

Neuroblastomas are embryonal cancers of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system with heterogeneous clinical presentation and course, ranging from tumors that undergo spontaneous regression to very aggressive tumors unresponsive to intensive multimodal therapy. The causes of most cases remain unknown. Advances in the treatment of children with these tumors have improved outcomes, although many with aggressive forms of neuroblastoma still succumb to their disease despite intensive therapy.

Epidemiology

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial solid tumor in children and the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in infants. Approximately 600 new cases are diagnosed each year in the United States, accounting for 8–10% of childhood malignancies and one third of cancers in infants. Neuroblastoma accounts for >15% of the mortality from cancer in children. The median age of children at diagnosis of neuroblastoma is 22 mo, and 90% of cases are diagnosed by 5 yr of age. The incidence is slightly higher in boys and in Caucasian populations.

Pathology

Neuroblastoma tumors, which are derived from primordial neural crest cells, form a spectrum with variable degrees of neural differentiation, ranging from tumors with primarily undifferentiated small round cells (neuroblastoma) to tumors consisting of mature and maturing schwannian stroma with ganglion cells (ganglioneuroblastoma or ganglioneuroma). The tumors may resemble other small round blue cell tumors, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The prognosis of children with neuroblastoma varies with the histologic features of the tumor, as dictated by the presence and amount of schwannian stroma, the degree of tumor cell differentiation, and the mitosis-karyorrhexis index.

Pathogenesis

The etiology of neuroblastoma in most cases remains unknown. Familial neuroblastoma accounts for 1–2% of all cases, is associated with a younger age at diagnosis, and is linked to mutations in the PHOX2B and ALK genes. The BARD1 gene has also been identified as a major genetic contributor to neuroblastoma risk. Neuroblastoma is associated with other neural crest disorders, including Hirschsprung disease, central hypoventilation syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1, and potentially congenital cardiovascular malformations (Table 525.1 ). Children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and hemihypertrophy also have a higher incidence of neuroblastoma. Increased incidence of neuroblastoma is associated with some maternal and paternal occupational chemical exposures, farming, and work related to electronics, although no single environmental exposure has been shown to directly cause neuroblastoma.

Table 525.1

ROHHAD, Rapid-onset obesity, hypothalamic dysfunction, hypoventilation, and autonomic dysregulation.

Adapted from Park JR, Eggert A, Caron H: Neuroblastoma: biology, prognosis, and treatment, Pediatr Clin North Am 55:97–120, 2008.

Genetic characteristics of neuroblastoma tumors that are of prognostic importance include amplification of the MYCN (N-myc ) protooncogene and tumor cell DNA content, or ploidy (Table 525.2 ). Amplification of MYCN is strongly associated with advanced tumor stage and poor outcomes. Hyperdiploidy confers better prognosis if the child is <18 mo old at diagnosis and if amplification of MYCN is not present. Other chromosomal abnormalities, including loss of heterozygosity of 1p, 11q, and 14q and gain of 17q, may be found in neuroblastoma tumors and have been associated with worse outcomes. In addition, many other biologic factors are associated with neuroblastoma outcomes, including tumor vascularity and the expression levels of nerve growth factor receptors (TrkA, TrkB), ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase, ganglioside GD2, neuropeptide Y, chromogranin A, CD44, multidrug resistance–associated protein, and telomerase. These factors and many others are under investigation in clinical trials to determine whether they can be used to reduce therapy for children predicted to fare well with minimal therapy or to intensify therapy for those predicted to be at high risk for relapse.

Table 525.2

International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Pretreatment Classification Schema

| INRG STAGE | AGE (mo) | HISTOLOGIC CATEGORY | GRADE OF TUMOR DIFFERENTIATION | MYC-N | 11Q ABERRATION | PLOIDY | PRETREATMENT RISK GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1/L2 |

GN Maturing GNB Intermixed |

A (very low) | |||||

| L1 |

Any, except GN Maturing or GNB Intermixed |

NA | B (very low) | ||||

| Amplified | K (high) | ||||||

| L2 | <18 |

Any, except GN Maturing or GNB Intermixed |

NA | No | D (low) | ||

| Yes | G (intermediate) | ||||||

| ≥18 | GNB nodular neuroblastoma | Differentiating | NA | No | E (low) | ||

| Yes | H (intermediate) | ||||||

| Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | NA | H (intermediate) | |||||

| Amplified | N (high) | ||||||

| M | <18 | NA | Hyperdiploid | F (low) | |||

| <12 | NA | Diploid | I (intermediate) | ||||

| 12 to <18 | NA | Diploid | J (intermediate) | ||||

| <18 | Amplified | O (high) | |||||

| ≥18 | P (high) | ||||||

| MS | <18 | NA | No | C (very low) | |||

| Yes | Q (high) | ||||||

| Amplified | R (high) |

GN, Ganglioneuroma; GNB, ganglioneuroblastoma; NA, not amplified.

From Pinto NR, Applebaum MA, Volchenboum SL, et al: Advances in risk classification and treatment strategies for neuroblastoma, J Clin Oncol 33(27):3008–3017, 2015 (Table 1).

Clinical Manifestations

Neuroblastoma may develop at any site of sympathetic nervous system tissue. Approximately half of neuroblastoma tumors arise in the adrenal glands, and most of the remainder originate in the paraspinal sympathetic ganglia. Metastatic spread , which is more common in children >1 yr old at diagnosis, occurs through local invasion or distant hematogenous or lymphatic routes. The most common sites of metastasis are the regional or distant lymph nodes, long bones and skull, bone marrow, liver, and skin. Lung and brain metastases are rare, occurring in <3% of cases.

The signs and symptoms of neuroblastoma reflect the tumor site and extent of disease and may mimic other disorders, which can result in a delayed diagnosis. Metastatic disease can cause a variety of signs and symptoms, including fever, irritability, failure to thrive, bone pain, cytopenias, bluish subcutaneous nodules, orbital proptosis, and periorbital ecchymoses (Fig. 525.1 ). Localized disease can manifest as an asymptomatic mass or can cause symptoms from mass effect, which in certain cases can result in spinal cord compression, bowel obstruction, and superior vena cava syndrome.

Children with neuroblastoma can also present with associated neurologic signs and symptoms. Neuroblastoma originating in the superior cervical ganglion can result in Horner syndrome. Paraspinal neuroblastoma tumors can invade the neural foramina, causing spinal cord and nerve root compression. Neuroblastoma can also be associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome of autoimmune origin, termed opsoclonus-myoclonus–ataxia syndrome , in which patients experience rapid, uncontrollable jerking eye and body movements, poor coordination, and cognitive dysfunction. Some tumors produce catecholamines that can cause increased sweating and hypertension, and may release vasoactive intestinal peptide, causing a profound secretory diarrhea. Children with extensive tumors can also experience tumor lysis syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Infants <18 mo old also can present in unique fashion, termed stage MS (previously 4S; see later), with widespread subcutaneous tumor nodules, massive liver involvement, limited bone marrow disease, and a small primary tumor without bone involvement or other metastases. The stage MS disease can spontaneously regress. The enigmatic characteristics of neuroblastoma with paraneoplastic syndromes and spontaneous regression under some circumstances have led some researchers to suggest that neuroblastoma may originate as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Diagnosis

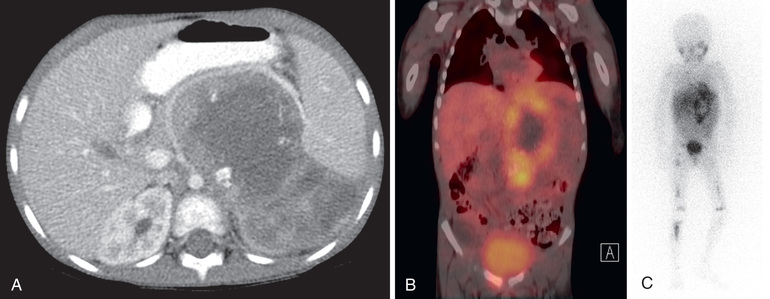

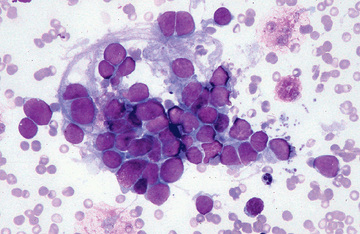

Neuroblastoma is usually discovered as a mass or multiple masses on plain radiography, CT, or MRI (Figs. 525.2A and 525.3 ). The mass often contains calcification and hemorrhage that can allow it to be appreciated on plain radiography or CT. Prenatal diagnosis of perinatal neuroblastoma on maternal ultrasound scans is sometimes possible. Tumor markers, including the catecholamine metabolites homovanillic acid (HVA) and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA), are elevated in the urine of approximately 95% of patients and help to confirm the diagnosis. A pathologic diagnosis is established from tumor tissue obtained by biopsy. Neuroblastoma can be confirmed without a primary tumor biopsy if small round blue tumor cells are observed in bone marrow samples (Fig. 525.4 ) and VMA or HVA levels are elevated in the urine.

Evaluations for metastatic disease should include CT or MRI of the chest and abdomen, bone scans to detect cortical bone involvement, and at least 2 independent bone marrow aspirations and biopsies to evaluate for marrow disease. Iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (123 I-MIBG) studies should be used when available to better define the extent of disease (see Fig. 525.2B and C ). PET combined with CT or MRI is another useful imaging method. MRI of the spine should be performed in cases with suspected or potential spinal cord compression, but imaging of the brain with either CT or MRI is not routinely performed unless dictated by the clinical presentation.

The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Staging System (INSS) is used to stage patients with neuroblastoma and is based on the extent of disease as determined by imaging at diagnosis. Extent of locoregional disease is based on specific local image-defined risk factors (IDRFs). L1 tumors (previously classified as INSS stage 1) are localized and confined to 1 body compartment without any IDRFs. L2 tumors (previously classified as INSS stages 2 and 3) refer to localized tumors with the presence of IDRFs. Disseminated tumors with metastases to bones, bone marrow, liver, distant lymph nodes, and other organs are staged as M (previously classified as INSS stage 4). Stage MS (previously stage 4S) refers to neuroblastoma in children <18 mo old with dissemination to liver, skin, or bone marrow without bone involvement and with a primary tumor that would otherwise be staged as L1 or L2.

Treatment

Treatment strategies for neuroblastoma have changed dramatically over the past 20 yr, with significant reduction in treatment intensity for children who have localized low-risk tumors and with continued increased treatment intensity and the addition of novel agents for treatment of children who have high-risk or recurrent disease. Patient age and tumor stage are combined with cytogenetic and molecular features of the tumor to determine the treatment risk group and estimated prognosis for each patient (see Table 525.2 ). Treatment for children with low-risk neuroblastoma typically includes surgery for stages L1 and L2 and observation for asymptomatic stage MS, with cure rates generally >90% without further therapy. Treatment with chemotherapy or radiation for the rare child with local recurrence can still be curative. Children with spinal cord compression at diagnosis may require urgent treatment with chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation to avoid neurologic damage. Stage MS neuroblastomas have a very favorable prognosis, and many regress spontaneously without therapy. Chemotherapy or resection of the primary tumor does not improve survival rates, but for infants with massive liver involvement and respiratory compromise, chemotherapy or radiation is used to alleviate symptoms. For children with stage MS neuroblastoma who require treatment for symptoms, the survival rate is 81%.

Treatment of intermediate-risk neuroblastoma includes surgery, chemotherapy, and in some cases, radiation therapy. The chemotherapy usually includes moderate doses of cisplatin or carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and doxorubicin given over several months. Radiation therapy is used for tumors with incomplete response to chemotherapy. Children with intermediate-risk neuroblastoma, including children with L2 disease and infants with M disease (both with favorable characteristics), have an excellent prognosis and >90% survival with this moderate treatment. In this intermediate-risk group, obtaining adequate diagnostic material for determination of the underlying biologic features of the tumor, such as the Shimada pathologic classification and MYCN gene amplification, is critical, so that children with unfavorable characteristics can receive more-aggressive treatment and those with favorable features can be spared excessive toxic therapy.

Children with high-risk neuroblastoma historically have had poor long-term survival rates between 25% and 35% with treatment that consisted of intensive chemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue, surgery, radiation, and 13-cis -retinoic acid (isotretinoin, Accutane). Induction chemotherapy for children with high-risk neuroblastoma includes combinations of cyclophosphamide, topotecan, doxorubicin, vincristine, cisplatin, and etoposide. After completion of induction chemotherapy, resection of the residual primary tumor is followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue and focal radiation therapy to tumor sites. A national cooperative group trial demonstrated significantly better survival with chemotherapy plus autologous stem cell rescue than with chemotherapy alone. The further addition of the differentiating agent 13-cis -retinoic acid following autologous stem cell transplantation resulted in further improvements in survival rates. In addition, a national clinical trial has demonstrated an increase in short-term survival rates with the addition of the monoclonal antibody (mAb) ch14.18 (dinutuximab ), interleukin-2, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to 13-cis -retinoic acid therapy. This mAb targets a diasialoganglioside, GD2, which has ubiquitous expression on neuroblastoma cells; incorporation of the mAb into consolidative therapy after autologous stem cell transplant improves the 2-yr event-free survival from 46.5% to 66.5%. Dinutuximab is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a standard of care for this subset of patients. The incorporation of tandem autologous stem cell transplant (2 separate autologous stem cell transplants with differing conditioning regimens) may further improve outcomes for patients with high-risk disease.

Cases of high-risk neuroblastoma are associated with frequent relapses, and children with recurrent neuroblastoma have a <50% response rate to alternative chemotherapy regimens. Therapies currently under investigation include new chemotherapeutic agents as well as novel therapies directed against critical intracellular signaling pathways, radiolabeled targeted agents (e.g., therapeutic 131 I-MIBG), immunotherapy, and antitumor vaccines.