Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Carola A.S. Arndt

The annual incidence of soft tissue sarcomas is 8.4 cases per 1 million white children younger than 14 yr of age. Rhabdomyosarcoma accounts for more than 50% of soft tissue sarcomas. The prognosis most strongly correlates with age and extent of disease at diagnosis, primary tumor site and histology, and expression of the fusion protein PAX-FOXO1.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Epidemiology

The most common pediatric soft tissue sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, accounts for approximately 3.5% of childhood cancers. These tumors may occur at virtually any anatomic site but are usually found in the head and neck (25%), orbit (9%), genitourinary tract (24%), and extremities (19%); retroperitoneal and other sites account for the remainder of primary sites. The incidence at each anatomic site is related to both patient age and tumor type. Extremity lesions are more likely to occur in older children and to have alveolar histology. Rhabdomyosarcoma occurs with increased frequency in patients with neurofibromatosis and other family cancer predisposition syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome (Table 527.1 ).

Table 527.1

Adapted from Parham DM, Alaggio R, Coffin CM: Myogenic tumors in children and adolescents, Pediatr Dev Path 15(1):S211–S236, 2012 (Table 2, p 214).

Pathogenesis

Rhabdomyosarcoma is thought to arise from the same embryonic mesenchyme as striated skeletal muscle, although a large percentage of these tumors arise in areas lacking skeletal muscle (e.g., bladder, prostate, vagina). On the basis of light microscopic appearance, rhabdomyosarcoma belongs to the general category of small, round cell tumors , which includes Ewing sarcoma, neuroblastoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Definitive diagnosis of a pathologic specimen requires immunohistochemical studies using antibodies to skeletal muscle (desmin, muscle-specific actin, myogenin) and, in the case of alveolar histology, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction or fluorescent in situ hybridization for PAX-FOXO1 transcript.

Determination of the specific histologic subtype (and in current studies, fusion status, i.e., FOXO1 positive or negative) is important in treatment planning and assessment of prognosis. There are 3 recognized histologic subtypes. The embryonal type accounts for approximately 60% of all cases and has an intermediate prognosis. The botryoid type, a variant of the embryonal form in which tumor cells and an edematous stroma project into a body cavity like a bunch of grapes, is found most often in the vagina, uterus, bladder, nasopharynx, and middle ear. The alveolar type accounts for approximately 25–40% of cases and often is characterized by the presence of PAX-FOXO1 fusion transcript (Table 527.2 ). The tumor cells tend to grow in nests that often have cleft-like spaces resembling alveoli. Alveolar tumors occur most often in the trunk and extremities and carry the poorest prognosis. The pleomorphic type (adult form) is rare in childhood, accounting for <1% of cases.

Table 527.2

From Parham DM, Alaggio R, Coffin CM: Myogenic tumors in children and adolescents, Pediatr Dev Path 15(1):S211–S236, 2012 (Table 3, p 214).

Clinical Manifestations

The most common presenting feature of rhabdomyosarcoma is a mass that may or may not be painful. Symptoms are caused by displacement or obstruction of normal structures (Table 527.1 ). Origin in the nasopharynx may be associated with nasal congestion, mouth breathing, epistaxis, and difficulty with swallowing and chewing. Regional extension into the cranium can produce cranial nerve paralysis, blindness, and signs of increased intracranial pressure with headache and vomiting. When the tumor develops in the face or cheek, there may be swelling, pain, trismus, and, as extension occurs, paralysis of cranial nerves. Tumors in the neck can produce progressive swelling with neurologic symptoms after regional extension. Orbital primary tumors are usually diagnosed early in their course because of associated proptosis, periorbital edema, ptosis, change in visual acuity, and local pain. When the tumor arises in the middle ear, the most common early signs are pain, hearing loss, chronic otorrhea, or a mass in the ear canal; extensions of tumor produce cranial nerve paralysis and signs of an intracranial mass on the involved side. An unremitting croupy cough and progressive stridor can accompany rhabdomyosarcoma of the larynx. Because most of these signs and symptoms also are associated with common childhood conditions, clinicians must be alert to the possibility of tumor.

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the trunk or extremities often is first noticed after trauma and initially may be regarded as a hematoma . If the swelling does not resolve or increases, malignancy should be suspected. Involvement of the genitourinary tract can produce hematuria, obstruction of the lower urinary tract, recurrent urinary tract infections, incontinence, or a mass detectable on abdominal or rectal examination. Paratesticular tumor usually manifests as a painless, rapidly growing mass in the scrotum. Vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma may manifest as a grapelike mass of tumor tissue bulging through the vaginal orifice, known as sarcoma botryoides , and can cause urinary tract or large bowel symptoms. Vaginal bleeding or obstruction of the urethra or rectum may occur. Similar findings can be noted with uterine primaries.

Tumors in any location may disseminate early and cause symptoms of pain or respiratory distress associated with pulmonary metastases. Extensive bone involvement can produce symptomatic hypercalcemia. In such cases, it may be difficult to identify the primary lesion.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma requires a high index of suspicion. The microscopic appearance is that of a small, round, blue cell tumor. Neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and Ewing sarcoma also are small, round, blue cell tumors from which suspected rhabdomyosarcomas must be differentiated. The differential diagnosis depends on the site of presentation. Definitive diagnosis is established by biopsy, microscopic appearance, and results of immunohistochemical stains and analysis of PAX/FOXO1 expression. A lesion in an extremity may be thought to be a hematoma or hemangioma ; an orbital lesion resulting in proptosis may be treated as an orbital cellulitis ; or bladder-obstructive symptoms may be missed. Adolescents may ignore or be embarrassed to mention paratesticular lesions for a long time. Unfortunately, several months often elapse between the initial symptoms and biopsy.

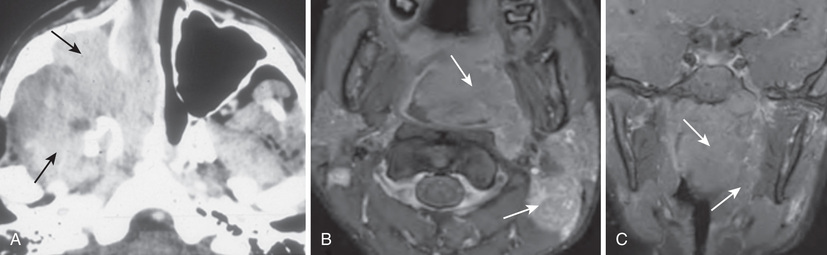

Diagnostic procedures are determined mainly by the area of involvement. CT or MRI is necessary for evaluation of the primary tumor site. With signs and symptoms in the head and neck area, radiographs should be examined for evidence of a tumor mass and for indications of bony erosion. MRI should be performed to identify intracranial extension or meningeal involvement and also to reveal bony involvement or erosion at the base of the skull. For abdominal and pelvic tumors, CT with a contrast agent or MRI can help delineate the tumor (Figs. 527.1 and 527.2 ). A radionuclide bone scan, chest CT, and bilateral bone marrow aspiration and biopsy should be performed to evaluate the patient for the presence of metastatic disease and to plan treatment. Certain low-risk patients may not need bone marrow evaluation. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography will help enhance staging.

The most critical element of the diagnostic workup is examination of tumor tissue , which includes the use of special histochemical stains and immunostains. Molecular genetics also is important to detect fusion transcripts present in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (PAX-FOX1). Lymph nodes also should be sampled for the presence of disease spread, especially in tumors of the extremities and in boys >10 yr old with paratesticular tumors.

Treatment

Treatment is multidisciplinary and includes the pediatric oncologist, pediatric surgeon or other surgical subspecialist, and most often the radiation oncologist. Only if the tumor is able to be completely resected, with negative margins, without loss of function or major cosmetic deformity, should this be attempted initially. Unfortunately, most rhabdomyosarcomas are not completely resectable at initial diagnosis. Treatment is based on risk classification of the tumor, which is determined by the stage of tumor, the tumor histology and/or fusion status, and the amount of tumor that was surgically resected before chemotherapy (“surgical group”). Stage is dependent on primary site (favorable vs unfavorable), tumor invasiveness (T1 or T2), lymph node status, tumor size, and presence of metastasis. Favorable sites include female genital, paratesticular, and head and neck (nonparameningeal) regions; all other sites are considered unfavorable. Table 527.3 shows the Children's Oncology Group staging system for rhabdomyosarcoma.

Table 527.3

Staging System for Rhabdomyosarcoma

| STAGE | SITE | T STAGE | SIZE | NODE STATUS | METASTASIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Favorable | T1 or T2 | a or b | N0 or N1 or Nx | M0 |

| 2 | Unfavorable | T1 or T2 | a | N0 or Nx | M0 |

| 3 | Unfavorable | T1 or T2 |

a b |

N1 N0 or N1 or Nx |

M0 |

| 4 | Any | T1 or T2 | a or b | N0 or N1 or Nx | M1 |

T1, Confined to anatomic site of origin; T2, extension and/or fixative to surrounding tissue.

Size: a, <5 cm in diameter; b, ≥5 cm in diameter.

Nodes: N0, regional nodes not involved; N1, regional nodes involved; Nx, regional node status unknown.

Metastases: M0, no distant metastases; M1, metastases present (includes positive cytology in cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, or peritoneal fluid).

Patients should be offered enrollment in clinical trials. Table 527.4 shows risk stratification and outcomes. Patients with low-risk disease can be cured with minimal therapy consisting of vincristine and of actinomycin, with or without lower doses of cyclophosphamide; radiation therapy can be used in the case of residual disease after initial surgery. Treatment for patients with intermediate-risk disease consists of vincristine, actinomycin, cyclophosphamide, and irinotecan along with radiation. For patients with high-risk disease, approaches using intensive multiagent chemotherapy have not improved the outcome, and new approaches are being investigated.

Table 527.4

Risk Groups and Outcome for Rhabdomyosarcoma, Children's Oncology Group

| RISK GROUP | STAGE/GROUP | HISTOLOGY | LONG-TERM EFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low, subset 1 |

Stage 1, Groups I-II Stage 1, Group III (orbit) Stage 2, Groups I-II |

Embryonal | 85–95% |

| Low, subset 2 |

Stage 1, Group III (nonorbit) Stage 3, Groups I-II |

Embryonal | 70–85% |

| Intermediate |

Stage 2-3, Group III Stage 1-3, Groups I-III |

Embryonal Alveolar |

73% 65% |

| High |

Stage 4, Group IV Stage 4, Group IV |

Embryonal Alveolar |

35% 15% |

EFS, Event-free survival.

From Hawkins DS, Spunt SL, Skapek SX: Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: soft tissue sarcomas, Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:1001–1008, 2013 (Table I, p 1002).

Prognosis

Prognostic factors include age, stage, histology/fusion status, and primary site. Among patients with resectable tumor and favorable histology, 80–90% have prolonged disease-free survival. Unresectable tumor localized to certain favorable sites, such as the orbit, also has a high likelihood of cure. Approximately 65–70% of patients with incompletely resected tumor also achieve long-term disease-free survival. Patients with disseminated disease have a poor prognosis; only approximately 50% achieve remission, and fewer than 50% of these are cured. Older children have a poorer prognosis than younger children. For all patients, surveillance for late effects of cancer treatment is extremely important. Late effects include infertility from cyclophosphamide, late effects in the radiation field (e.g., bladder dysfunction, infertility, cataracts, impaired bone growth), and secondary malignancies.

Other Soft Tissue Sarcomas

The nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas constitute a heterogeneous group of tumors that account for 3% of all childhood malignancies (Table 527.5 ). Because they are relatively rare in children, much of the information about their natural history and treatment has been derived from studies in adult patients. In children, the median age at diagnosis is 12 yr, with a male/female ratio of 2.3 : 1. These tumors usually arise in the trunk or lower extremities. The most common histologic types are synovial sarcoma (42%), fibrosarcoma (13%), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (12%), and neurogenic tumors (10%). Molecular genetic studies often prove useful in diagnosis, because several of these tumors have characteristic chromosomal translocations. Tumor size, stage (clinical group), invasiveness, and histologic grade correlate with survival.

Table 527.5

Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy, but a careful search for lung and bone metastases should be undertaken before surgical excision. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy should be considered for large, high-grade, and/or unresectable tumors. The role of chemotherapy for nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas is not as well defined as for rhabdomyosarcoma. Patients with large (>5 cm), high-grade, or unresectable or metastatic disease are treated with multiagent chemotherapy in addition to irradiation and/or surgery. Patients with completely resected small (<5 cm) tumors are generally treated with surgery alone and can be expected to have an excellent outcome regardless of whether the tumor is high or low grade.