Headaches

Andrew D. Hershey, Marielle A. Kabbouche, Hope L. O'Brien, Joanne Kacperski

Headache is a common complaint in children and adolescents. Headaches can be a primary problem or occur as a symptom of another disorder (a secondary headache). Recognizing this difference is essential for choosing the appropriate evaluation and treatment to ensure successful management of the headache. Primary headaches are most often recurrent, episodic headaches and for most children are sporadic in their presentation.

The most common forms of primary headache in childhood are migraine and tension-type headaches (Table 613.1 ). Other forms of primary headache, including the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias and cluster headaches, occur much less commonly. Primary headache can progress to very frequent or even daily headaches with chronic migraine and chronic tension-type headaches being increasingly recognized as a problem for children and adolescents. These more frequent headaches can have an enormous impact on the life of the child and adolescent, as reflected in school absences and decreased school performance, social withdrawal, and changes in family interactions. To reduce this impact, a treatment strategy that incorporates acute treatments, preventive treatments, and biobehavioral therapies must be implemented.

Table 613.1

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013.

Secondary headache is a headache that is a symptom of an underlying illness (see Table 613.1 ). The underlying illness should be clearly present as a direct cause of the headaches with close association of timing and symptomatology. This is often difficult when two or more common conditions occur in close temporal association. This frequently leads to the misdiagnosis of a primary headache as a secondary headache. This is, for example, the case when migraine is misdiagnosed as a sinus headache. In general, the key components of a secondary headache are the likely direct cause-and-effect relationship between the headache and the precipitating condition. In this regard, when the presumed cause of the secondary headache has been treated (antibiotics) or given adequate time to recover (posttraumatic headache), the headache symptoms should have resolved. If this does not occur, either the diagnosis must be reevaluated or the effectiveness of the treatment reassessed.

In all instances of primary headaches, the neurologic examination should be normal. If it is not normal or a secondary headache is suspected, this raises a red flag. The presence of an abnormal neurologic examination or unusual neurologic symptoms is a key clue that additional investigation is warranted.

Migraine

Andrew D. Hershey, Marielle A. Kabbouche, Hope L. O'Brien, Joanne Kacperski

Migraine is the most frequent type of recurrent headache that is brought to the attention of parents and primary care providers, but it remains underrecognized and undertreated, particularly in children and adolescents. Migraine is characterized by episodic attacks that may be moderate to severe in intensity, focal in location on the head, have a throbbing quality, and associated with nausea, vomiting, light sensitivity, and/or sound sensitivity. Compared with migraine in adults, pediatric migraine may be shorter in duration and has a bilateral, often bifrontal, location. Migraine can also be associated with an aura that may be typical (visual, sensory, or dysphasic) or atypical (hemiplegic, Alice in Wonderland syndrome) (Tables 613.2 to 613.6 ). In addition, a number of migraine variants have been described and, in children, include abdominally related symptoms without headache, and components of the periodic syndromes of childhood (see Table 613.1 ). Treatment of migraine requires the incorporation of an acute treatment plan, a preventive treatment plan if the migraine occurs frequently or is disabling, and a biobehavioral plan to help cope with both the acute attacks and frequent or persistent attacks if present.

Table 613.2

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013, Table 4.

Table 613.3

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013, Table 6.

Table 613.4

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013, Table 7.

Table 613.5

Vestibular Migraine With Vertigo

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013, Table 8.

Table 613.6

From Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, ed 3 (beta version), Cephalalgia 33(9):629-808, 2013, Table 9.

Epidemiology

Up to 75% of children report having a significant headache by the time they are 15 yr of age. Recurrent headaches are less common, but remain highly frequent. Migraine has been reported to occur in up to 10.6% of children between the ages of 5 and 15 yr and up to 28% of older adolescents. When headaches are occurring more than 15 days a month they are termed chronic migraine and may occur in up to 1% of children and adolescents. The risk of conversion to a daily headache becomes more likely as the frequency increases or ineffective acute treatments are utilized. This explains the necessity to treat the headaches aggressively or prevent the headaches altogether, trying to block transformation to chronic migraine.

Migraine can impact a patient's life through school absences, limitation of home activities, and restriction of social activities. This can be assessed through simple tools such as PedMIDAS. As headaches become more frequent, their negative impact increases in magnitude. This can lead to further complications, including anxiety and school avoidance, requiring a more extensive treatment plan.

Classification and Clinical Manifestations

Criteria have been established to guide the clinical and scientific study of headaches; these are summarized in The International Classification of Headache Disorders , 3rd edition (ICHD-3 beta). Table 613.1 contrasts the different clinical types of migraine; Tables 613.2 to 613.6 list the specific criteria for migraine types.

Migraine Without Aura

Migraine without aura is the most common form of migraine in both children and adults. The ICHD-3 beta (see Table 613.2 ) requires this to be recurrent (at least five headaches that meet the criteria, typically over the past year, but no firm time period is required). The recurrent episodic nature helps differentiate this from a secondary headache, as well as separates migraine from tension-type headache. Because headaches may first start in young childhood, this may limit the diagnosis in children as they are just be beginning to have headaches.

The duration of the headache is defined as 4-72 hr for adults. It has been recognized that children may have shorter-duration headaches, so an allowance has been made to reduce this duration to 2-72 hr in children and adolescents under the age of 18 yr. Note that this duration is for the untreated or unsuccessfully treated headache. Furthermore, if the child falls asleep with the headache, the entire sleep period is considered part of the duration. These duration limits help differentiate migraine from both short-duration headaches, including the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, and prolonged headaches, such as those caused by idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Some prolonged headaches may still be migraine, but a migraine that persists beyond 72 hr is classified as a variant termed status migrainosus.

The quality of migraine pain is often, but not always, throbbing or pounding. This may be difficult to elicit in young children and drawings or demonstrations may help confirm the throbbing quality.

The location of the pain has classically been described as unilateral (hemicrania); in young children it is more commonly bilateral. A more appropriate way to think of the location would therefore be focal, to differentiate it from the diffuse pain of tension-type headaches. Of particular concern is the exclusively occipital headache because although these can be migraines, they are more frequently secondary to another more proximate etiology such as posterior fossa abnormalities.

Migraine, when allowed to fully develop, often worsens in the face of and secondarily results in altered activity level. For example, worsening of the pain occurs classically in adults when going up or down stairs. This history is often not elicited in children. A change in the child's activity pattern can be easily observed as a reduction in play or physical activity. Older children may limit or restrict their sports activity or exercise during a headache attack.

Migraine may have a variety of associated symptoms. In younger children, nausea and vomiting may be the most obvious symptoms and often outweigh the headache itself. This often leads to the overlap with several of the gastrointestinal periodic diseases, including recurrent abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting, cyclic vomiting, and abdominal migraine. The common feature among all of these related conditions is an increased propensity among children with them for the later development of migraine. Oftentimes, early childhood recurrent vomiting may in fact be migraine, but the child is not asked about or is unable to describe headache pain. This may occur as early as infancy because babies with colic have a higher incidence of migraine once they are able to express their symptoms. Once a clear head pain becomes evident, the earlier diagnosis of a gastrointestinal disorder is no longer appropriate.

When headache is present, vomiting raises the concern of a secondary headache, particularly related to increased intracranial pressure. One of the red flags for this is the daily or near daily early morning vomiting, or headaches waking the child up from sleep. When the headaches associated with vomiting episodes are sporadic and not worsening, it is more likely that the diagnosis is migraine. Vomiting and headache caused by increased intracranial pressure are frequently present on first awakening and remit with maintenance of upright posture. In contrast, if a migraine is present on first awakening (a relatively infrequent occurrence in children), getting up and going about normal, upright activities usually makes the headache and vomiting worse.

As the child matures, light and sound sensitivity (photophobia and phonophobia) may become more apparent. This is either by direct report of the patient or the interpretation by the parents of the child's activity because the parent may become aware of this symptom before the child. These symptoms are likely a component of the hypersensitivity that develops during an acute migraine attack and may also include smell sensitivity (osmophobia) and touch sensitivity (cutaneous allodynia). Although only the photophobia and phonophobia are components of the ICHD-3 beta criteria, these other symptoms are helpful in confirming the diagnosis and may be helpful in understanding the underlying pathophysiology and determining the response to treatment. The final ICHD-3 beta requirement is the exclusion of causes of secondary headaches, and this should be an integral component of the headache history.

Migraine typically runs in families with reports of up to 90% of children having a first- or second-degree relative with recurrent headaches. Given the underdiagnoses and misdiagnosis in adults, this is often not recognized by the family, and a headache family history is required. When a family history is not identified, this may be the result of either a lack of awareness of migraine within the family or an underlying secondary headache in the child. Any child whose family, upon close and both direct and indirect questioning, does not include individuals with migraine or related syndromes (e.g., motion sickness, cyclic vomiting, menstrual headache) should have an imaging procedure performed to look for anatomic etiologies for headache.

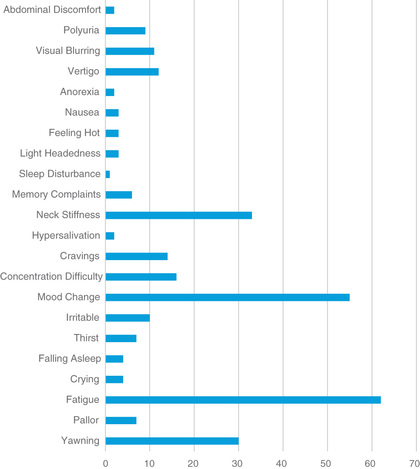

In addition to the classifying features, there may be additional markers of a migraine disorder. These include such things as triggers (skipping meals, inadequate or irregular sleep, dehydration, and weather changes are the most common), pattern recognition (associated with menstrual periods in adolescents or Monday-morning headaches resulting from changes in sleep patterns over the weekend and nonphysiologic early waking on Monday mornings for school), and prodromal symptoms (a feeling of irritability, tiredness, and food cravings prior to the start of the headache) (Fig. 613.1 ). Although these additional features may not be consistent, they do raise the index of suspicion for migraine and provide a potential mechanism of intervention. In the past, food triggers were considered widely common, but the majority have either been discredited with scientific study or represent such a small number of patients that they only need to be addressed when consistently triggering the headache.

Migraine With Aura

The aura associated with migraine is a neurologic warning that a migraine is going to occur. In the common forms this can be the start of a typical migraine or a headache without migraine, or it may even occur in isolation. For a typical aura, the aura needs to be visual, sensory, or dysphasic, lasting longer than 5 min and less than 60 min with the headache starting within 60 min (see Table 613.3 ). The importance of the aura lasting longer than 5 min is to differentiate the migraine aura from a seizure with a postictal headache, whereas the 60-min maximal duration is to separate migraine aura from the possibility of a more prolonged neurologic event such as a transient ischemic attack. In a revision to the ICHD-3b criteria, it has been suggested that for a diagnosis of aura there needs to be a positive symptom and not just a loss of function (flashing lights, tingling).

The most common type of visual aura in children and adolescents is photopsia (flashes of light or light bulbs going off everywhere). These photopsias are often multicolored and when gone, the child may report not being able to see where the flash occurred. Less likely in children are the typical adult auras, including fortification spectra (brilliant white zigzag lines resembling a starred pattern castle) or shimmering scotoma (sometimes described as a shining spot that grows or a sequined curtain closing). In adults, the auras typically involve only half the visual field, whereas in children they may be randomly dispersed. Blurred vision is often confused as an aura but is difficult to separate from photophobia or difficulty concentrating during the pain of the headache.

Sensory auras are less common. They typically occur unilaterally. Many children describe this sensation as insects or worms crawling from their hand, up their arm, to their face with a numbness following this sensation. Once the numbness occurs, the child may have difficulty using the arm because they have lost sensory input, and a misdiagnosis of hemiplegic migraine may be made.

Dysphasic auras are the least-common type of typical aura and have been described as an inability or difficulty to respond verbally. The patient afterward will describe an ability to understand what is being asked, but cannot answer back. This may be the basis of what in the past has been referred to as confusional migraine, and special attention needs to be paid to asking the child about this possibility and their degree of understanding during the initial phases of the attack. Most of the time, these episodes are described as a motor aphasia, and they are often associated with sensory or motor symptoms.

Much less commonly, atypical forms of aura can occur, including hemiplegia (true weakness, not numbness, and may be familial), vertigo or lower cranial nerve symptoms (formerly called basilar-type, formerly thought to be caused by basilar artery dysfunction, now thought to be a more brainstem-based migraine with brainstem aura) (see Table 613.4 ), and distortion (Alice in Wonderland syndrome). Whenever these rarer forms of aura are present, further investigation is warranted. Not all motor auras can be classified as hemiplegic migraine spectrum, and they should be differentiated from those very specific migrainous events, because the diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine has genetic, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic implications.

Hemiplegic migraine is one of the better-known forms of rare auras. This transient unilateral weakness usually lasts only a few hours but may persist for days. Both familial and sporadic forms have been described. The familial hemiplegic migraine is an autosomal dominant disorder with mutations described in three separate genes: CACNA1A, ATP1A2, and SCN1A. Some patients with familial hemiplegic migraine have other yet-to-be-identified genetic mutations. Multiple polymorphisms have been described for these genes. Hemiplegic migraines may be triggered by minor head trauma, exertion, or emotional stress. The motor weakness is usually associated with another aura symptom and may progress slowly over 20-30 min, first with a visual aura and then, in sequence, with sensory, motor, aphasic, and basilar auras. Headache is present in more than 95% of patients and usually begins during the aura; headache may be unilateral or bilateral and may have no relationship to the motor weakness. Some patients may develop attacks of coma with encephalopathy, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis, and cerebral edema. Long-term complications may include seizures, repetitive daily episodes of blindness, cerebellar signs with the development of cerebellar atrophy, and mental retardation.

Migraine with brainstem aura (basilar-type migraine) was formerly considered a disease of the basilar artery because many of the unique symptoms were attributed to dysfunction in this area of the brainstem. Some of the symptoms described include vertigo, tinnitus, diplopia, blurred vision, scotoma, ataxia, and an occipital headache. The pupils may be dilated, and ptosis may be evident.

Syndrome of transient headache and neurologic deficits with CSF lymphocytosis (HaNDL) describes transient migraine-like headaches associated with neurologic deficits (motor, sensory, language impairments) and CSF showing pleocytosis. It is considered a self-limited migraine-like syndrome of unknown etiology and is rarely reported in the pediatric population.

Childhood periodic syndromes are a group of potentially related symptoms that occur with increased frequency in children with migraine. The hallmark of these symptoms is the recurrent episodic nature of the events. Some of these have included gastrointestinal-related symptoms (colic, motion sickness, recurrent abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting including cyclic vomiting, and abdominal migraine), sleep disorders (sleepwalking, sleep talking, and night terrors), unexplained recurrent fevers, and even seizures.

The gastrointestinal symptoms span the spectrum from the relatively mild (motion sickness on occasional long car rides) to severe episodes of uncontrollable vomiting that may lead to dehydration and the need for hospital admission to receive fluids. These latter episodes may occur on a predictable time schedule and hence have been called cyclic vomiting. During these attacks, the child may appear pale and frightened but does not lose consciousness. After a period of deep sleep, the child awakens and resumes normal play and eating habits as if the vomiting had not occurred. Many children with cyclic vomiting have a positive family history of migraine and as they grow older have a higher than average likelihood of developing migraine. Cyclic vomiting may be responsive to migraine-specific therapies; careful attention is needed for fluid replacement if the vomiting is excessive. Cyclic vomiting of migraine must be differentiated from gastrointestinal disorders, including intestinal obstruction (malrotation, intermittent volvulus, duodenal web, duplication cysts, superior mesenteric artery compression, and internal hernias), peptic ulcer, gastritis, giardiasis, chronic pancreatitis, and Crohn disease. Abnormal gastrointestinal motility and pelviureteric junction obstruction can also cause cyclic vomiting. Metabolic causes include disorders of amino acid metabolism (heterozygote ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency), organic acidurias (propionic acidemia, methylmalonic acidemia), fatty acid oxidation defects (medium-chain acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency), disorders of carbohydrate metabolism (hereditary fructose intolerance), acute intermittent porphyria, and structural central nervous system lesions (posterior fossa brain tumors, subdural hematomas or effusions). The diagnosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, and children will need a full workup to be labeled as having cyclic vomiting syndrome. Cyclic vomiting syndrome is more frequent in younger children and will gradually transform into a typical migraine attack by puberty (see Chapter 369 ).

The diagnosis of abdominal migraine can be confusing but can be thought of as a migraine without the headache. Like a migraine, it is an episodic disorder characterized by midabdominal pain with pain-free periods between attacks. At times this pain is associated with nausea and vomiting (thus crossing into the recurrent abdominal pain or cyclic vomiting spectrum). The pain is usually described as dull and may be moderate to severe. The pain may persist from 1-72 hr and, although it is usually in the midline, it may be periumbilical or poorly localized by the child. To meet the criteria of abdominal migraine, the child must complain at the time of the abdominal pain of at least two of the following: anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or pallor. As with cyclic vomiting, a thorough history and physical examination with appropriate laboratory studies must be completed to rule out an underlying gastrointestinal disorder as a cause of the abdominal pain. Careful questioning about the presence of headache or head pain needs to be addressed directly to the child because many times, this is truly a migraine but in the child's mind (as well as the parents’ observation), the abdominal symptoms are paramount.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

A thorough history and physical examination, including a neurologic examination with special focus on headache, has been shown to be the most sensitive indicator of an underlying etiology. The history needs to include a thorough evaluation of the prodromal symptoms, any potential triggering events or timing of the headaches, associated neurologic symptoms, and a detailed characterization of the headache attacks, including frequency, severity, duration, associated symptoms, use of medication, and disability. The disability assessment should include the impact on school, home, and social activities and can easily be assessed with tools such as PedMIDAS. A family history of headaches and any other neurologic, psychiatric, and general health conditions is also important both for identification of migraine within the family as well as the identification of possible secondary headache disorders. The familial penetrance of migraine is so robust that the absence of a family history of migraine or its equivalent phenomena should raise the concern that the diagnosis may not be migraine and warrants further history taking, referral to a headache specialist, or investigation. The lack of a family history may be due to a lack of awareness of the family of the migraine (“doesn't everybody get headaches?”). When headaches are refractory, a history of potential comorbid conditions, which includes mood disorders and illicit substance use, especially in teenagers, that may influence adherence and acceptability of the treatment plan, may also need to be addressed. Patients with difficult to treat chronic migraines may have raised intracranial pressure; a lumbar puncture with lowering of the pressure may resolve the migraine. These patients may not have papilledema. In addition, disorders such as CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy), Moyamoya disease, and SMART (stoke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy) may initially present with migraines.

Neuroimaging is warranted when the neurologic examination is abnormal or unusual neurologic features occur during the migraine; when the child has headaches that awaken the child from sleep or that are present on first awakening and remit with upright posture; when the child has brief headaches that only occur with cough or bending over; when the headache is mostly in the occipital area; and when the child has migrainous headache with an absolutely negative family history of migraine or its equivalent (e.g., motion sickness, cyclic vomiting; Table 613.7 ). In this case, an MRI is the imaging method of choice because it provides the highest sensitivity for detecting posterior fossa lesions and does not expose the child to radiation.

Table 613.7

Indications for Neuroimaging in a Child With Headaches

| Abnormal neurologic examination |

| Abnormal or focal neurologic signs or symptoms |

| Seizures or very brief auras (<5 min) |

| Unusual headaches in children |

| Headache in children younger than 6 yr old or any child who cannot adequately describe his or her headache |

| Brief cough headache in a child or adolescent |

| Headache worst on first awakening or that awakens the child from sleep |

| Migrainous headache in the child with no family history of migraine or its equivalent |

In the child with a headache that is instantaneously at its worst at onset, a CT scan looking for blood is the best initial test; if it is negative, a lumbar puncture should be done looking especially for xanthochromia of the CSF. There is no evidence that laboratory studies or an electroencephalogram is beneficial in a typical migraine without aura or migraine with aura.

Treatment

Table 613.8 outlines the drugs used to manage migraine headaches in children. The American Academy of Neurology established useful practice guidelines for the management of migraine as follows:

Table 613.8

Drugs Used in the Management of Migraine Headaches in Children

| DRUG | DOSE | MECHANISM | SIDE EFFECTS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACUTE MIGRAINE | ||||

| Analgesics | ||||

| Acetaminophen | 15 mg/kg/dose | Analgesic effects | Overdose, fatal hepatic necrosis | Effectiveness limited in migraine |

| Ibuprofen | 7.5-10 mg/kg/dose | Antiinflammatory and analgesic | GI bleeding stomach upset, kidney injury | Avoid overuse (2-3 times per wk) |

| Triptans | ||||

| Almotriptan* (ages 12-17 yr) | 12.5 mg | 5-HT1b/1d agonist | Vascular constriction, serotonin symptoms such as flushing, paresthesias, somnolence, GI discomfort | Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| Eletriptan | 40 mg | Same | Same | Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| Frovatriptan | 2.5 mg | Same | Same |

May be effective for menstrual migraine prevention Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| Naratriptan | 2.5 mg | Same | Same |

May be effective for menstrual migraine prevention Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| Rizatriptan* (ages 6-17 yr) | 5 mg for child weighing <40 kg, 10 mg | Same | Same |

Available in tablets and melts Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo.) |

| Sumatriptan |

Oral: 25, 50, 100 mg Nasal: 10 mg SC: 6 mg |

Same | Same | Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| Zolmitriptan (NS ages 12+) |

Oral: 2.5, 5 mg Nasal: 5 mg* |

Same | Same |

Available in tablets and melts Avoid overuse (>4-6 times per mo) |

| PROPHYLAXIS (NONE APPROVED BY FDA FOR CHILDREN) | ||||

| Calcium Channel Blockers | ||||

| Flunarizine † | 5 mg HS | Calcium channel blocking agent | Headache, lethargy, dizziness | May ↑ to 10 mg HS |

| Anticonvulsants | ||||

| Valproic acid | 20 mg/kg/24 hr (begin 5 mg/kg/24 hr) | ↑ Brain GABA | Nausea, pancreatitis, fatal hepatotoxicity | ↑ 5 mg/kg every 2 wk |

| Topiramate* (12-17 yr) | 100-200 mg divided bid | ↑ Activity of GABA | Fatigue, nervousness | Increase slowly over 12-16 wk |

| Levetiracetam | 20-60 mg/kg divided bid | Unknown | Irritability, fatigue | Increase every 2 wk starting at 20 mg/kg divided bid |

| Gabapentin | 900-1800 mg divided bid | Unknown | Somnolence, fatigue aggression, weight gain | Begin 300 mg, ↑ 300 mg/wk |

| Antidepressants | ||||

| Amitriptyline | 1 mg/kg/day | ↑ CNS serotonin and norepinephrine | Cardiac conduction, abnormalities and dry mouth, constipation, drowsiness, confusion |

Increase by 0.25 mg/kg every 2 wk Morning sleepiness reduced by administration at dinnertime |

| Antihistamines | ||||

| Cyproheptadine | 0.2-0.4 mg/kg divided bid; max: 0.5 mg/kg/24 hr | H1 -receptor and serotonin agonist | Drowsiness, thick bronchial secretions | Preferred in children who cannot swallow pills; not well tolerated in adolescents |

| Antihypertensive | ||||

| Propranolol | 10-20 mg tid | Nonselective β-adrenergic blocking agent | Dizziness, lethargy | Begin 10 mg/24 hr ↑ 10 mg/wk (contraindicated in asthma and depression) |

| Others | ||||

| Coenzyme Q10 | 1-3 mg/kg/day | Increases fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria | No adverse effects reported | Fat soluble; ensure brand contains small amount of vitamin E to help absorption |

| Riboflavin | 50-400 mg daily | Cofactor in energy metabolism | Bright yellow urine, polyuria and diarrhea | |

| Magnesium | 9 mg/kg divided tid | Cofactor in energy metabolism | Diarrhea or soft stool | |

| Butterbur | 50-150 mg daily | May act similar to a calcium channel blocker | Burping | |

| OnabotulinumtoxinA | 100 units (age 11-17 yr) | Inhibits acetylcholine release from nerve endings | Ptosis, blurred vision, hematoma at injection site | Used off label in children |

| SEVERE INTRACTABLE | ||||

| Prochlorperazine | 0.15 mg/kg/IV; max dose 10 mg | Dopamine antagonist | Agitation, drowsiness, muscle stiffness, akinesia and akathisia | May have increased effectiveness when combined with ketorolac and fluid hydration |

| Metoclopramide | 0.2 mg/kg IV; 10 mg max dose | Dopamine antagonist | Drowsiness, urticaria, agitation, akinesia and akathisia | Caution in asthma patients |

| Ketorolac | 0.5 mg/kg IV; 15 mg max dose | Antiinflammatory and analgesic | GI upset, bleeding | |

| Valproate sodium injection | 15 mg/kg IV: 1,000 mg max dose | ↑ Brain GABA | Nausea, vomiting, somnolence, thrombocytopenia | Would avoid in hepatic disease |

| Dihydroergotamine IV |

0.5 mg/dose every 8 hr (<40 kg) 1.0 mg/dose every 8 hr (>40 kg) |

Nausea, vomiting, vascular constriction, phlebitis | Dose may need to be adjusted for side effects (decrease) or limited effectiveness (increase) | |

| Nasal spray |

0.5-1.0 mg/dose 0.5 mg/spray |

|||

* FDA approved in the pediatric population.

† Available in Europe.

↑, Increase; CNS, central nervous system; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GI, gastrointestinal; hs, at night; SC, subcutaneous.

- Reduction of headache frequency, severity, duration, and disability

- Reduction of reliance on poorly tolerated, ineffective, or unwanted acute pharmacotherapies

- Improvement in quality of life

- Avoidance of acute headache medication escalation

- Education and enabling of patients to manage their disease to enhance personal control of their migraine

- Reduction of headache-related distress and psychological symptoms

To accomplish these goals, three components need to be incorporated into the treatment plan: (1) An acute treatment strategy should be developed for stopping a headache attack on a consistent basis with return to function as soon as possible, with the goal being 2 hr maximum; (2) a preventive treatment strategy should be considered when the headaches are frequent (one or more per week) and disabling; and (3) biobehavioral therapy should be started, including a discussion of adherence, elimination of barriers to treatment, and healthy habit management.

Acute Treatment

Management of an acute attack is to provide headache freedom as quickly as possible with return to normal function. This mainly includes two groups of medicines: nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and triptans. Most migraine headaches in children will respond to appropriate doses of NSAIDs when they are administered at the onset of the headache attack. Ibuprofen has been well documented to be effective at a dose of 7.5-10.0 mg/kg and is often preferred; however, acetaminophen (15 mg/kg) can be effective in those with a contraindication to NSAIDs. Special concern for the use of ibuprofen or other NSAIDs includes ensuring that the children can recognize and respond to onset of the headache. This means discussing with the child the importance of telling the teacher when the headache starts at school and ensuring that proper dosing guidelines and permission have been provided to the school. In addition, overuse needs to be avoided, limiting the NSAID (or any combination of nonprescription analgesics) to not more than 2-3 times per week. The limitation of any analgesic to not more than three headaches a week is necessary to prevent the transformation of the migraines into medication-overuse headaches. If a patient has maximized the weekly allowance of analgesics, the patient's next step is to only use hydrating fluids for the rest of the week as an abortive approach. If ibuprofen is not effective, naproxen sodium also may be tried in similar doses. Aspirin is also a reasonable option but is usually reserved for older children (>16 yr). Use of other NSAIDs has yet to be studied in pediatric migraine. The goal of the primary acute medication should be headache relief within 1 hr with return to function in 10 of 10 headaches.

When a migraine is especially severe, NSAIDs alone may not be sufficient. In this case, a triptan may be considered. Multiple studies have demonstrated their effectiveness and tolerability. There are currently three triptans that are approved by the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of episodic migraine in the pediatric population. Almotriptan is approved for the treatment of acute migraine in adolescents (ages 12-17 yr). Rizatriptan is approved for the treatment of migraine in children as young as age 6 yr. The intranasal formulation of zolmitriptan was recently approved by the FDA in the United States for use in children ages 12 and over. Several studies have shown it to provide rapid and effective relief, and it has been demonstrated to be well tolerated for treatment of acute migraine in patients 12 yr and older. Zolmitriptan nasal spray may be of particular benefit to those with nausea and in patients who have difficulty swallowing tablets.

The combination of naproxen sodium and sumatriptan has been studied and may be effective in children. Controlled clinical trials demonstrate that intranasal sumatriptan is safe and effective in children older than age 8 yr with moderate to severe migraine. At present, pediatric studies showing the effectiveness of oral sumatriptan are lacking, and there is insufficient evidence to support the use of subcutaneous sumatriptan in children. For most adolescents, dosing is the same as for adults; a reduction in dose is made for children weighing less than 40 kg. The triptans vary by rapidity of onset and biologic half-life. This is related to both their variable lipophilicity and dose. Clinically, 60–70% of patients respond to the first triptan tried, with 60–70% of the patients who did not respond to the first triptan responding to the next triptan. Therefore, in the patient who does not respond to the first triptan in the desired way (rapid reproducible response without relapse or side effects), it is worthwhile to try a different triptan. The most common side effects of the triptans are caused by their mechanism of action—tightness in the jaw, chest, and fingers as a result of vascular constriction and a subsequent feeling of grogginess and fatigue from the central serotonin effect. The vascular constriction symptoms can be alleviated through adequate fluid hydration during an attack.

The most effective way to administer acute treatment is with the recognition that NSAIDs and triptans have different mechanisms of action. NSAIDs are used for all headaches, mild to severe, with their use being restricted to fewer than two to three attacks per week; the triptans are added for moderate to severe headaches, with their use being restricted to not more than four to six attacks per month. For an acute attack, the NSAIDs can be repeated once in 3-4 hr, if needed for that specific attack, and the triptans can be repeated once in 2 hr if needed. It is important to consider the various formulations available, and these options should be discussed with pediatric patients and their parents, especially if a child is unable to swallow pills or take an oral dose because of nausea.

Because vascular dilation is a common feature of migraine that may be responsible for some of the facial flushing, followed by paleness and the lightheaded feeling accompanying the attacks, fluid hydration should be integrated into the acute treatment plan. For oral hydration, this can include the sports drinks that combine electrolytes and sugar to provide the intravascular rehydration.

Antiemetics were used for acute treatment of the nausea and vomiting. Further study has identified that their unique mechanism of effectiveness in headache treatment is related to their antagonism of dopaminergic neurotransmission. Therefore, the antiemetics with the most robust dopamine antagonism (i.e., prochlorperazine and metoclopramide) have the best efficacy. These can be very effective for status migrainosus or a migraine that is unresponsive to the NSAIDs and triptans. They require intravenous administration because other forms of administration of these drugs are less effective than the NSAIDs or triptans. When combined with ketorolac and intravenous fluids in the emergency department or an acute infusion center, intravenous antiemetics can be very effective. When they are not effective, further inpatient treatment may be required using dihydroergotamine (DHE), which will mean an admission to an inpatient unit for more aggressive therapy of an intractable attack.

Emergency Department Treatments for Intractable Headaches

When an acute migraine attack does not respond to the recommended outpatient regimen and the headache is disabling, more aggressive therapeutic approaches are available and may be necessary to prevent further increase in the duration as well as the frequency of headaches. These migraines fall into the classification of status migrainosus and patients may need to be referred to an infusion center, the emergency room, or an inpatient unit.

Available specific treatments for migraine headache in an emergency room setting include the following: antidopaminergic medications such as prochlorperazine and metoclopramide; NSAIDs such as ketorolac; vasoconstrictor medications such as DHE; and antiepileptic drugs such as sodium valproate.

Antidopaminergic Drugs: Prochlorperazine and Metoclopramide

The use of antidopaminergic medications is not limited to controlling the nausea and vomiting often present during a migraine headache. Their potential pharmacologic effect may be a result of their antidopamine property and the underlying pathologic process involving the dopaminergic system during a migraine attack. Prochlorperazine is very effective in aborting an attack in the emergency room when given intravenously with a bolus of intravenous fluid. Results show a 75% improvement with 50% headache freedom at 1 hr and 95% improvement with 60% headache freedom at 3 hr. Prochlorperazine may be more effective than metoclopramide. The average dose of metoclopramide is 0.13-0.15 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of 10 mg given intravenously over 15 min. The average dose of prochlorperazine is 0.15 mg/kg, with a maximum dose of 10 mg. These medications are usually well-tolerated, but extrapyramidal reactions are more frequent in children than older persons. An acute extrapyramidal reaction can be controlled in the emergency room with 25-50 mg of diphenhydramine given intravenously. There is no need for premedication with diphenhydramine to prevent side effects. Diphenhydramine should only be used if needed when side effects are present.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs: Ketorolac

It is known that an aseptic inflammation occurs in the central nervous system as a result of the effect of multiple reactive peptides in patients with migraines. Ketorolac is often used in the emergency department as monotherapy for a migraine attack or in combination with other drugs. In monotherapy, the response to ketorolac is 55.2% improvement. When the ketorolac is combined with prochlorperazine, the response rate jumps to 93%.

Antiepileptic Drugs: Sodium Valproate

Antiepileptic drugs have been used as prophylactic treatment for migraine headache for years with adequate double-blinded, controlled studies on their efficacy in adults. The mechanism in which sodium valproate acutely aborts migraine headaches is not well understood. Sodium valproate is given as a bolus of 15-20 mg/kg push (over 10 min). This intravenous load is followed by an oral dose (15-20 mg/day) in the 4 hr after the injection. Patients may benefit from a short-term preventive treatment with an extended-release form after discharge from the emergency room. Sodium valproate is usually well tolerated. Patients should be receiving a fluid load during the procedure to prevent a possible hypotensive episode.

Triptans

Subcutaneous sumatriptan (0.06 mg/kg) has an overall efficacy of 72% at 30 min and 78% at 2 hr, with a recurrence rate of 6%. Because children tend to have a shorter duration of headache, a recurrence rate of 6% would seem appropriate for this population. DHE, if recommended for the recurrences, should not be given in the 24 hr after triptan use. Triptans are contraindicated in patients treated with ergotamine within 24 hr and within 2 wk of treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Triptans may rarely produce a serotonin syndrome in patients taking a serotonin receptor reuptake inhibitor. Both triptans and ergotamine are contraindicated in hemiplegic migraines.

Dihydroergotamine (DHE)

DHE is an old migraine medication used as a vasoconstrictor to abort the vascular phase of migraine headache. The effectiveness is discussed in detail in the section Inpatient Management of Intractable Migraine and Status Migrainosus, below. One dose of DHE can be effective for abortive treatment in the emergency department. Emergency room treatment of migraine shows a recurrence rate of 29% at 48-72 hr, with 6% of patients needing even more aggressive therapy in an inpatient unit.

Inpatient Management of Intractable Migraine and Status Migrainosus

Six to 7% of patients fail acute treatment in the emergency department. These patients are usually admitted for 3-5 days and receive extensive parenteral treatment. A child should be admitted to the hospital for a primary headache when the child is in status migrainosus, has an exacerbation of a chronic severe headache, or has an analgesic overuse headache with an acute exacerbation. The goal of inpatient treatment is to control a headache that has been unresponsive to other abortive therapy and is disabling to the child. Treatment protocols include the use of DHE, antiemetics, sodium valproate, and other drugs.

Dihydroergotamine

Ergots are one of the oldest treatments for migraine headache. DHE is a parenteral form used for acute exacerbations. Its effect stems from the 5HT1A-1B-1D-1F receptor agonist affinity and central vasoconstriction. DHE has a greater α-adrenergic antagonist activity and is less vasoconstrictive peripherally. Before initiation of an intravenous ergot protocol, a full history should be obtained and a neurologic examination performed. Females of childbearing age should be evaluated for pregnancy before ergots are administered.

The DHE protocol consists of the following: Patients are premedicated with 0.13-0.15 mg/kg of prochlorperazine 30 min prior to the DHE dose (maximum of three prochlorperazine doses to prevent extrapyramidal syndrome; after 3 doses of prochlorperazine a non-dopamine antagonist antiemetic should be used, such as ondansetron). A dose of 0.5-1.0 mg of DHE is used (depending on age and tolerability) every 8 hr until headache freedom. The first dose should be divided into two half doses separated by 30 min; they are considered test doses. When the headache ceases, an extra dose is given in an attempt to prevent recurrence after discharge. The response to this protocol is a 97% improvement and 77% headache freedom. The response is noticeable by the fifth dose; the drug can reach its maximum effects after the tenth dose. Side effects of DHE include nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, a flushed face, and increased blood pressure. The maximum dose used in this protocol is 15 mg total of DHE.

Sodium Valproate

Sodium valproate is used when DHE is contraindicated or has been ineffective. One adult study recommends the use of valproate sodium as follows: Bolus with 15 mg/kg (maximum of 1,000 mg), followed by 5 mg/kg every 8 hr until headache freedom or up to a maximum of ten doses. Always give an extra dose after headache ceases. This protocol was studied in adults with chronic daily headaches and showed an 80% improvement. It is well tolerated and is useful in children when DHE is ineffective, contraindicated, or not tolerated.

Other Inpatient Therapies

During an inpatient admission for status migrainosus, we highly recommend that other services, such as behavioral medicine and holistic medicine, become involved if they are available. The behavioral medicine staff can play a major role in talking to patients about their specific triggers and can also evaluate school, as well as home and social, stressors. The staff would also initiate some coping skills during the admission and evaluate the necessity for further outpatient follow-up for cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, or treatment for other comorbidities. The holistic medicine staff, when consulted, can offer holistic approaches to pain control, including relaxation techniques, as well as medical massage and craniosacral therapy.

Preventive Therapy

When the headaches are frequent (more than one headache per week) or disabling (causing the patient to miss school, home, or social activities, or having a PedMIDAS score > 20), preventive or prophylactic therapy may be warranted. The goal of this therapy should to be to reduce the frequency (to one to two headaches or fewer per month) and level of disability (PedMIDAS score < 10). Prophylactic agents should be given for at least 4-6 mo at an adequate dose and then weaned over several weeks. Evidence in adult studies has begun to demonstrate that persistent frequent headaches foreshadow an increased risk of progression with decreased responsiveness and increased risk of refractoriness in the future. It is unclear whether this also occurs in children and/or adolescents and whether early treatment of headache in childhood prevents development of refractory headache in adulthood.

Multiple preventive medications have been utilized for migraine prophylaxis in children. When analyzed as part of a practice parameter, only one medication, flunarizine (a calcium channel blocking agent), demonstrated a level of effectiveness viewed as substantial; it is not available in the United States. Flunarizine is typically given at 5 mg orally daily and increased after 1 mo to 10 mg orally daily, with a month off of the drug every 4-6 mo.

A commonly used preventive therapy for headache and migraine is amitriptyline. Typically, a dose of 1 mg/kg daily at dinner or in the evening is effective. However, this dose needs to be reached slowly (i.e., over weeks, with an increase every 2 wk until the goal is reached) to minimize side effects and improve tolerability. Side effects include sleepiness and those related to amitriptyline's anticholinergic activity. Weight gain has been observed in adults using amitriptyline but is a less frequent occurrence in children. Amitriptyline does have the potential to exacerbate the prolonged QT syndrome, so it should be avoided in patients with this diagnosis and looked for in patients taking the drug who complain of a rapid or irregular heart rate.

Antiepileptic medications are also used for migraine prophylaxis, with topiramate, valproic acid, and levetiracetam having been demonstrated to be effective in adults. There are limited studies in children for migraine prevention, but all of these medications have been assessed for safety and tolerability in children with epilepsy.

Topiramate has become widely used for migraine prophylaxis in adults. Topiramate was also demonstrated to be effective in an adolescent study. This study demonstrated that a 25-mg dose twice a day was equivalent to placebo, whereas a 50-mg dose twice a day was superior. Thus it appears that the adult dosing schedule is also effective in adolescents with an effective dosage range of 50 mg twice a day to 100 mg twice a day. This dose needs to be reached slowly to minimize the cognitive slowing associated with topiramate use. Side effects include weight loss, paresthesias, kidney stones, lowered bicarbonate levels, decreased sweating, and rarely glaucoma and changes in serum transaminases. In addition, in adolescent females taking birth control pills, the lowering of the effectiveness of the birth control by topiramate needs to be discussed.

A comparative effectiveness study in children (8-17 yr) of the two most common treatments (amitriptyline and topiramate) compared with placebo (the CHAMP study) demonstrated that all three treatments were effective, but there was not statistical superiority for amitriptyline or topiramate over placebo.

Valproic acid has long been used for epilepsy in children and has been demonstrated to be effective in migraine prophylaxis in adults. The effective dose in children appears to be 10 mg/kg orally twice a day. Side effects of weight gain, ovarian cysts, and changes in serum transaminases and platelet counts need to be monitored. Other antiepileptics, including lamotrigine, levetiracetam, zonisamide, gabapentin, and pregabalin, are also used for migraine prevention.

β-Blockers have long been used for migraine prevention. The studies on β-blockers have a mixed response pattern with variability both between β-blockers and between patients with a given β-blocker. Propranolol is the best studied for pediatric migraine prevention with unequivocally positive results. The contraindication for use of propranolol in children with asthma or allergic disorders or diabetes and the increased incidence of depression in adolescents using propranolol limit its use somewhat. It may be very effective for a mixed subtype of migraine (basilar-type migraine with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome). This syndrome has been reported to be responsive to propranolol. α-Blockers and calcium channel blockers, aside from flunarizine, also have been used in pediatric migraine; their effectiveness, however, remains unclear.

In very young children, cyproheptadine may be effective in prevention of migraine or the related variants. Young children tend to tolerate the increased appetite induced by the cyproheptadine and tend not to be subject to the lethargy seen in older children and adults; the weight gain is limiting once children start to enter puberty. Typical dosing is 0.1-0.2 mg/kg orally twice a day.

Nutraceuticals have become increasingly popular over the past few years, especially among families who prefer a more natural approach to headache treatment. Despite studies showing success of these therapies in adults, few studies have shown effectiveness in pediatric headaches. Riboflavin (vitamin B2 ), at doses ranging from 25-400 mg, is the most widely studied with good results. Side effects are minimal and include bright yellow urine, diarrhea, and polyuria. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation may be effective in reducing migraine frequency at doses of 1-2 mg/kg/day. Butterbur is also effective in reducing headaches, with minimal side effects, including burping. Use in children has been limited to avoid the potential toxicity of butterbur-containing pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which are naturally contained and are a known carcinogen and toxic to the liver.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is the first medication FDA-approved for chronic migraine in adults. There are studies in children indicating its effectiveness; use in children is considered off-label. The limited available studies revealed the following: The average dose used was 188.5 units ± 32 units with a minimum dose of 75 units and maximum of 200 units. The average age of patients receiving the treatment was 16.8 ± 2.0 yr (minimum 11 yr; maximum 21 yr). OnabotulinumtoxinA injections improved disability scores (PedMIDAS) and headache frequency in pediatric chronic daily headache patients and chronic migraine in this age-group. OnabotulinumtoxinA not only had a positive effect on the disability scoring for these young patients with headache but was also able to transform the headaches from chronic daily to intermittent headaches in more than 50% of the patients.

Eptinezumab, Erenumab, Galcanezumab, and Fremanezumab—humanized monoclonal antibodies against the calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor—have demonstrated safety and efficacy in adult patients with migraine. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved these agents for use in adults with migraine, including chronic migraine. As yet, there are no completed studies in children and adolescents.

Biobehavioral Therapy

Biobehavioral evaluation and therapy are essential for effective migraine management. This includes identification of behavioral barriers to treatment, such as a child's shyness or limitation in notifying a teacher of the start of a migraine or a teacher's unwillingness to accept the need for treatment. Additional barriers include a lack of recognition of the significance of the headache problem and reverting to bad habits once the headaches have responded to treatment. Adherence is equally important for acute and preventive treatment. The need to have a sustained response, long enough to prevent relapse (to stay on preventive medication), is often difficult when the child starts to feel better. Establishing a defined treatment goal (one or two or fewer headaches per month for 4-6 mo) helps with acceptance.

Because many of the potential triggers for frequent migraines (skipping meals, dehydration, decreased or altered sleep) are related to a child's daily routine, a discussion of healthy habits is a component of biobehavioral therapy. This should include adequate fluid intake without caffeine, regular exercise, not skipping meals and making healthy food choices, and adequate (8-9 hr) sleep on a regular basis. Sleep is often difficult in adolescents because middle and high schools often have very early start times, and the adolescent's sleep architecture features a shift to later sleep onset and waking. This has been one of the explanations for worsening headaches during the school year in general and at the beginning of the school year and week.

Biofeedback-assisted relaxation and cognitive behavioral therapy (usually in combination with amitriptyline) are effective for both acute and preventive therapy and may be incorporated into this multiple treatment strategy. This provides the child with a degree of self-control over the headaches and may further help the child cope with frequent headaches.

Young Adults and the Transition of Headache Care From a Pediatric to an Adult Provider

Migraine is a chronic condition that begins in childhood. Males are diagnosed at a younger age than females; however, during development, the prevalence becomes highest among women, starting at puberty. Some adolescents and women report migraine associated with menses; the pain symptoms are described as lasting longer and having a higher intensity. The role of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) is often a topic of discussion among female adolescents and young women. Studies have shown improvement of menstrual migraine in adult patients taking oral estrogens and progesterone; similar studies have not been done in adolescents. OCPs are not approved by the U.S. FDA for treatment of menstrual migraine; they have been associated with an increased risk of stroke among women with migraine aura. Therefore, their use in adolescents as a prophylactic agent is not advised.

Comorbid conditions such as anxiety and depression are seen with a high prevalence among adults with migraine; however, the prevalence among adolescent patients remains unclear. Diagnostic tools capable of differentiating mood disorders from pain symptoms in the pediatric population are limited, which makes identifying those at risk challenging. However, it is important to keep in mind the potential of mood disorders, especially in young adults.

Remission of migraine is seen in up to 34% of adolescents, and almost 50% continue to have migraine persisting into adulthood. Despite the high prevalence, the transition of care in this population has yet to be studied. Successful transition of care from a pediatric to an adult provider has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with chronic disease.

Early diagnosis and treatment of migraine can help minimize the progression of the disease in adults. This, together with careful screening for comorbid conditions, may help identify those at risk for refractory migraine, minimize disability, and improve overall headache outcomes.

Bibliography

Abu-Arafeh I. Flunarizine for the prevention of migraine—a new look at an old drug. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2012;54:200–207.

Afridi SK, Giffin NJ, Kaube H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in migraine with prolonged aura. Neurology . 2013;80:642–647.

Ahmed K, Oas K, Mack KJ, et al. Experience with botulinum toxin type A in medically intractable pediatric chronic daily headache. Pediatr Neurol . 2010;43(5):316–319.

Ahonen K, Hamalainen ML, Rantala H, et al. Nasal sumatriptan is effective in treatment of migraine attacks in children: a randomized trial. Neurology . 2004;62(6):883–887.

Anttila V, Stefansson H, Kallela M, et al. Genome-wide association study of migraine implicates a common susceptibility variant on 8q22.1. Nat Genet . 2010;42(10):869–873.

Armstrong AE, Gillan E, DiMario FJ Jr. SMART syndrome (stroke-like migraine attacks after radiation therapy) in adult and pediatric patients. J Child Neurol . 2014;29(3):336–341.

Arruda MA, Bigal ME. Migraine and migraine subtypes in preadolescent children. Neurology . 2012;79:1881–1888.

Avraham SB, Har-Gil M, Watemberg N. Acute confusional migraine in an adolescent: response to intravenous valproate. Pediatrics . 2010;125:e956–e959.

Barón J, Mulero P, Pedraza MI, et al. HaNDL syndrome: correlation between focal deficits topography and EEG or SPECT abnormalities in a series of 5 new cases. Neurologia . 2016;31(5):305–310.

Berger K, Evers S. Migraine with aura and the risk of increased mortality. BMJ . 2010;341:465–466.

Bond DS, Vithiananthan S, Nash JM, et al. Improvement of migraine headaches in severely obese patients after bariatric surgery. Neurology . 2013;76:1135–1138.

Bruijn J, Duivenvoorden H, Passchier J, et al. Medium-dose riboflavin as a prophylactic agent in children with migraine: a preliminary placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial. Cephalalgia . 2010;30(12):1426–1434.

Bruijn J, Locher H, Passchier J, et al. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with migraine in clinical studies: a systematic review. Pediatrics . 2010;126:323–332.

Chasman DI, Schürks M, Anttila V, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals three susceptibility loci for common migraine in the general population. Nat Genet . 2011;43:695–697.

Condo M, Posar A, Arbizzania A, et al. Riboflavin prophylaxis in pediatric and adolescent migraine. J Headache Pain . 2009;10:361–365.

Connelly M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of pediatric chronic migraine. JAMA . 2013;310:2617–2618.

Crawford MJ, Lehman L, Slater S, et al. Menstrual migraine in adolescents. Headache . 2009;49:341–347.

Derosier FJ, Lewis D, Hershey AD, et al. Randomized trial of sumatriptan and naproxen sodium combination in adolescent migraine. Pediatrics . 2012;126:e1411–e1420.

DeSimone R, Ranieri A, Montella S, et al. Intracranial pressure in unresponsive chronic migraine. J Neurol . 2014;261(7):1365–1373.

Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Reed KL, et al. Safety and efficacy of peripheral nerve stimulation of the occipital nerves for the management of chronic migraine: long-term results from a randomized, multicenter, double-blinded controlled study. Cephalalgia . 2015;35(4):344–358.

Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al. Onabotulinumtoxin A for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache . 2010;50:921–936.

Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet . 2018;391:1315–1330.

Edvinsson L, Linde M. New drugs in migraine treatment and prophylaxis: telcagepant and topiramate. Lancet . 2010;376:645–654.

Fernstermacher N, Levin M, Ward T. Pharmacological prevention of migraine. BMJ . 2011;342:d583.

Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Solorzano C, et al. Randomized study of IV procholorperazine plus diphenhydramine vs IV hydromorphone for migraine. Neurology . 2017;89:2075–2082.

Fumal A, Vandenheede M, Coppola G, et al. The syndrome of transient headache with neurological deficits and CSF lymphocytosis (HaNDL): electrophysiological findings suggesting a migrainous pathophysiology. Cephalalgia . 2005;25:754–758.

Garg P, Servoss SJ, Wu JC, et al. Lack of association between migraine headache and patent foramen ovale: results of a case-control study. Circulation . 2010;121:1406–1412.

Gelfand AA, Fullerton HJ, Goadsby PJ. Child neurology: migraine with aura in children. Neurology . 2010;75:e16–e19.

Gelfand AA, Goadsbury PJ. Treatment of pediatric migraine in the emergency room. Pediatr Neurol . 2012;47:233–241.

Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(22):2123–2132.

Graf WD, Kayyali HR, Abdelmoity AT, et al. Incidental neuroimaging findings in nonacute headache. J Child Neurol . 2010;25(10):1182–1187.

Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. Coenzyme Q10 deficiency and response to supplementation in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Headache . 2007;47:73–80.

Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology . 2001;57:2034–2039.

Holroyd KA, Bendtsen L. Tricyclic antidepressants for migraine and tension-type headaches. BMJ . 2010;341:5250.

Hougaard A, Amin F, Hauge AW, et al. Provocation of migraine with aura using natural trigger factors. Neurology . 2013;80:1–4.

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Hayashino Y. Botulism toxin A for prophylactic treatment of migraine and tension headaches in adults. JAMA . 2012;307:1736–1744.

Kabbouche M, O'Brien H, Hershey AD. OnabotulinumtoxinA in pediatric chronic daily headache. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep . 2012;12(2):114–117.

Kabbouche MA, Cleves C. Evaluation and management of children and adolescents presenting with an acute setting. Semin Pediatr Neurol . 2010;17(2):105–108.

Karsan N, Prabhakar P, Goadsby PJ. Characterizing the premonitory stage of migraine in children: a clinic-based study of 100 patients in a specialist headache service. J Headache Pain . 2016;17:94.

Kelley SA, Hartman AL, Kossoff EH. Comorbidity of migraine in children presenting with epilepsy to a tertiary care center. Neurology . 2012;79:468–473.

Lateef T, Cui L, Heaton L, et al. Validation of a migraine interview for children and adolescents. Pediatrics . 2013;131:e96–e102.

Lewis D, Winner P, Saper J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topiramate for migraine prevention in pediatric subjects 12 to 17 years of age. Pediatrics . 2009;123:924–934.

Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Neurology . 2004;63:2215–2224.

Lewis DW. Pediatric migraine. Neurol Clin . 2009;27:481–501.

Loder E. Triptan therapy in migraine. N Engl J Med . 2010;363:63–70.

Mariotti P, Nociti V, Cianfoni A, et al. Migraine-like headache and status migrainosus as attacks of multiple sclerosis in a child. Pediatrics . 2010;126:e459–e464.

McCandless RT, Arrington CB, Nielson DC, et al. Patent foramen ovale in children with migraine headaches. J Pediatr . 2011;159:243–247.

McKeage K. Zolmitriptan nasal spray: a review in acute migraine in pediatric patients aged 12 years and older. Paediatr Drugs . 2016;18(1):75–81.

Mohamed BP, Goadsby PJ, Prabhakar P. Safety and efficacy of flunarizine in childhood migraine: 11 years’ experience, with emphasis on its effect in hemiplegic migraine. Dev Med Child Neurol . 2012;54:274–277.

Oelkers-Ax R, Leins A, Parzer P, et al. Butterbur root extract and music therapy in the prevention of childhood migraine: an explorative study. Eur J Pain . 2008;12:301–313.

Palm-Meinders IH, Koppen H, Terwindt GM, et al. Structural brain changes in migraine. JAMA . 2012;308:1889–1896.

Pascual J, Valle N. Pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis. Curr Pain Headache Rep . 2003;7:224–228.

Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med . 2017;376:115–124.

Powers SW, Kahhikar-Zuck S, Allen JR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy plus amitriptyline for chronic migraine in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2013;310:2622–2630.

Pringsheim T, Becker WJ. Triptans for symptomatic treatment of migraine headache. BMJ . 2014;348:35–37.

Rabbie R, Derry S, Moore RA. Ibuprofen with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2013;(4) [CD008039].

Russell MB, Ducros A. Sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol . 2011;10:457–470.

Schoenen J, Vandersmissen B, Jeangette S, et al. Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator. Neurology . 2013;80:697–704.

Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(22):2113–2122.

Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology . 2012;78:1337–1345.

Silberstein SD, Rosenberg J. Multispecialty consensus on diagnosis and treatment of headache. Neurology . 1553;54:2000.

Taggert E, Doran S, Kokotillo A, et al. Ketorolac in the treatment of acute migraine: a systematic review. Headache . 2013;53:277–287.

The Medical Letter. A fixed-dose combination of sumatriptan and naproxen for migraine. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2008;50:45–46.

The Medical Letter. Treatment of migraine. Med Lett . 2017;59:27–32.

The Medical Letter. Warning against the use of valproate for migraine prevention during pregnancy. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2013;55:45.

Tikka S, Baumann M, Siitonen M, et al. CADASIL and CARASIL. Brain Pathol . 2014;24:525–544.

van Ooserhout WPJ, van der Plas AA, van Zwet EW, et al. Postdural puncture headache in migraineurs and nonheadache subjects. Neurology . 2013;80:941–948.

Visser WH, Winner P, Strohmaier K, et al. Rizatriptan 5 mg for the acute treatment of migraine in adolescents: results from a double-blind, single-attack study and two open-label, multiple-attack studies. Headache . 2004;44:89–899.

Winner P, Rothner D, Saper J, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sumatriptan nasal spray in the treatment of acute migraine in adolescents. Pediatrics . 2000;106:9889–9997.

Secondary Headaches

Andrew D. Hershey, Marielle A. Kabbouche, Hope L. O'Brien, Joanne Kacperski

Headaches can be a common symptom of other underlying illnesses. In recognition of this, the ICHD-3 beta has classified potential secondary headaches (see Table 613.1 ). The key to the diagnosis of a secondary headache is to recognize the underlying cause and demonstrate a direct cause and effect. Until this has been done, the diagnosis is speculative. This is especially true when the suspected etiology is common.

Headache is a common occurrence following concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), reported in as many as 86% of high school and college athletes who have suffered from head trauma. Although there are no strict criteria for determining who will develop persistent headache following concussion, it is important to gather information to rule out other secondary headaches and significant primary headache disorders and to identify those who may be at risk for persistent headache following concussion.

Chronic or persistent headaches are headaches that last for more than 3 mo following head trauma. This definition is consistent with the classification of persistent posttraumatic headaches in the ICHD-3b. Although concussion and posttraumatic headache are rapidly evolving areas of study, there is an unfortunate lack of definitive scientific evidence at this time on these topics in pediatrics. The ICHD-3 classifies posttraumatic headaches as acute if they last less than 3 mo and persistent if they last more than 3 mo. This time period is consistent with ICHD-II diagnostic criteria, although the term persistent has been adopted in place of chronic. Although the ICHD-3 criteria state that posttraumatic headaches begin within 7 days after injury to the head or after regaining consciousness, the authors comment that this 7-day cutoff is arbitrary, and some experts believe that headaches may develop after a longer interval. Some studies have shown that about half of children with posttraumatic headache 3 mo after concussion had a history of preexisting headaches, and 31% had a history of migraine or probable migraine before the injury. Furthermore, 56% of patients with headaches at 3 mo following injury had a family history of migraine. Based on our clinical experience and studies of patients with prolonged postconcussion symptoms in general, we have concerns that those with prior concussion and persistent posttraumatic headaches, preexisting anxiety and/or depression, and maladaptive coping styles may also be at higher risk for persistent posttraumatic headache. One study investigating risk factors for prolonged postconcussion syndrome supports these theories; the researchers found that a personal or family history of mood disorders or migraine, as well as prior concussion and delayed symptom onset, were associated with symptoms for ≥ 3 mo following concussion.

Despite being classified as a secondary headache, a posttraumatic headache generally presents with clinical features that are observed in primary headache disorders, including tension-type, migraine, and cervicogenic headaches. The few reports that have thus far assessed the characteristics of posttraumatic headache in the pediatric population have also reported various proportions of migraine or tension-type characteristics, with the reported prevalence of each varying among individual studies.

Although headache is reported to be the most common symptom following concussion, there is a paucity of studies regarding the safety and efficacy of headache treatments for persistent posttraumatic headaches. As most clinicians who manage concussion and posttraumatic headaches can attest, these headaches may be difficult to treat. There are currently no established guidelines for their treatment, especially when persistent, and practices can vary widely. Most treatment algorithms proposed have been extrapolated from the primary headache literature and small noncontrolled trials of posttraumatic headache regimens. When posttraumatic headaches become problematic or persistent, a multidimensional management approach, including pharmacologic intervention, physical rehabilitation, and cognitive-behavioral therapies, are often used. Management should therefore be relevant to the type of headache and also focused on the clinical needs of the child.

Like primary headache disorders, these headaches can have a substantial effect on the child's life, leading to lost school days and withdrawal from social interactions. Referral for biobehavioral therapy and coping strategies may be necessary. Adherence should be promoted and can be optimized by educating both the patient and the family about the proper use of acute and prophylactic medications, establishing realistic expectations including expectations for recovery, and emphasizing compliance at the initiation of treatment.

Children with persistent posttraumatic headaches may require frequent analgesics. Rebound headaches are common and can complicate treatment. The excessive use of symptomatic headache medicines, most commonly simple analgesics, can cause medication-overuse headaches in susceptible patients and has been well-described in patients with primary headache disorders. Medication overuse can be a contributing factor in headache chronicity in 20–30% of children and adolescents, with chronic daily headache unrelated to concussion. Because analgesics are commonly recommended for the treatment of acute headaches following concussion, some susceptible patients with concussion are at risk for developing a medication-overuse pattern that causes a chronic headache syndrome.

There is no clear evidence to help guide the clinician on the timing of initiation of preventive therapy in children to decrease the likelihood of developing persistent posttraumatic headaches. Although many medications are being used to manage persistent posttraumatic headaches, most have supporting data for management of migraine or chronic migraine and few have been studied for the treatment of persistent posttraumatic headaches in a systematic manner.

Sinus headache is the most overdiagnosed form of recurrent headache. Although no studies have evaluated the frequency of misdiagnosis of an underlying migraine as a sinus headache in children, in adults, it has been found that up to 90% of adults diagnosed as having a sinus headache either by themselves or their physician appear to have migraine. When headaches are recurrent and respond within hours to analgesics, migraine should be considered first. In the absence of purulent nasal discharge, fever, or chronic cough, the diagnosis of sinus headache should not be made.

Medication-overuse headaches (MOHs) frequently complicate primary and secondary headaches. An MOH is defined as a headache present for more than 15 days/mo for longer than 3 mo and intake of a simple analgesic on more than 15 days/mo and/or prescription medications, including triptans or combination medications, on more than 10 days/mo. Some of the signs that should raise suspicion of medication overuse are the increasing use of analgesics (nonprescription or prescription) with either decreased effectiveness or frequent wearing off (i.e., analgesic rebound). An MOH can be worsened by ineffective medications or misdiagnosis of the headache. Patients should be cautioned against the frequent use of antimigraine medications, including combination analgesics or triptans.

Serious causes of secondary headaches are likely to be related to increased intracranial pressure. This can be caused by a mass (tumor, vascular malformation, cystic structure) or an intrinsic increase in pressure (idiopathic intracranial hypertension, also known as pseudotumor cerebri). In the former case, the headache is caused by the mass effect and local pressure on the dura; in the latter case, the headache is caused by diffuse pressure on the dura. The etiology of idiopathic intracranial hypertension may be the intake of excessive amounts of fat-soluble compounds (e.g., vitamin A, retinoic acid, and minocycline), hormonal changes (increased incidence in females), or blockage of venous drainage (as with inflammation of the transverse venous sinus from mastoiditis). When increased pressure is suspected, either by historical suspicion or the presence of papilledema, an MRI with magnetic resonance angiography and magnetic resonance venography should be performed, followed by a lumbar puncture if no mass or vascular anomaly is noted. The lumbar puncture can be diagnostic and therapeutic of idiopathic intracranial hypertension but must be performed with the patient in a relaxed recumbent position with legs extended, because abdominal pressure can artificially raise intracranial pressure. If headache persists or there are visual field changes, pharmaceutical treatment with a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, optic nerve fenestration, or a shunt needs to be considered.