Neurocutaneous Syndromes

Mustafa Sahin, Nicole Ullrich, Siddharth Srivastava, Anna Pinto

The neurocutaneous syndromes include a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by abnormalities of both the integument and central nervous system (CNS) of variable severity (Table 614.1 ). Many of the disorders are hereditary and believed to arise from a defect in differentiation of the primitive ectoderm (nervous system, eyeball, retina, and skin). Disorders classified as neurocutaneous syndromes include neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), von Hippel–Lindau disease (VHL), PHACE (posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta, cardiac defects, eye abnormalities) syndrome, ataxia-telangiectasia (AT), linear nevus syndrome, hypomelanosis of Ito, and incontinentia pigmenti.

Table 614.1

Genetic and Clinical Features Associated With Neurocutaneous Syndromes

| SYNDROME | GENE(S) | INHERITANCE | CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberous sclerosis complex |

TSC1 (tuberous sclerosis 1; hamartin) TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis 2; tuberin) |

Autosomal dominant | Angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, ungual fibromas, cortical dysplasias, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, subependymal nodules, intellectual disability, epilepsy including infantile spasms, autism spectrum disorder, retinal hamartomas, cardiac rhabdomyomas, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, renal angiomyolipomas |

| Von Hippel–Lindau | VHL (von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor) | Autosomal dominant | Cerebellar hemangioblastomas, retinal angiomas, endolymphatic sac tumors, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, renal cysts, renal cell carcinomas, pheochromocytomas |

| Linear nevus sebaceous |

HRAS (HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase) KRAS (KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase) NRAS (neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog) |

Somatic mosaicism | Linear sebaceous nevus, hemimegalencephaly, ventriculomegaly, intellectual disability, epilepsy, ocular defects (e.g., strabismus), cardiac defects (e.g., coarctation of the aorta), urogenital defects (e.g., horseshoe kidney), skeletal defects (e.g., fibrous dysplasia) |

| PHACE | Unknown | Posterior fossa malformations, hemangiomas, arterial lesions (e.g., dysplasia of cerebral arteries), cardiac defects (e.g., coarctation of the aorta), ocular defects (e.g., microphthalmia), ventral defects (e.g., sternal clefting) | |

| Incontinentia pigmenti | IKBKG (inhibitor of kappa B kinase gamma) | X-linked dominant | Distinctive skin lesion appearing in four stages (bullous, verrucous, pigmentary, atretic), alopecia, dental anomalies (e.g., hypodontia), intellectual disability, epilepsy, ocular defects (e.g., retinal neovascularization), nail defects (e.g., dystrophic nails) |

Neurofibromatosis

Nicole Ullrich

The neurofibromatoses are autosomal dominant disorders that cause tumors to grow on nerves and result in other systemic abnormalities. There are three types, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1), neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2), and schwannomatosis, all of which are clinically and genetically distinct diseases and should be considered separate entities.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

NF1 has an incidence of 1 in 3,000 live births and is caused by autosomal dominant loss-of-function mutations in the NF1 gene. Approximately 50% are inherited from an affected parent, and the other 50% result from a sporadic gene mutation. The disease is clinically diagnosed when any two of the following seven features are present: (1) six or more café-au-lait macules > 5 mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals and > 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals (Fig. 614.1 ). Café-au-lait macules (CALMs) are the hallmark of neurofibromatosis and are present in almost 100% of patients. They are present at birth but increase in size, number, and pigmentation, especially during the first few years of life. The CALMs are scattered over the body surface, with predilection for the trunk and extremities. CALMs are not specific for NF1 and may be observed in other disorders (Table 614.2 ). (2) Axillary or inguinal freckling consisting of multiple hyperpigmented areas 2-3 mm in diameter (Fig. 614.2 ). Skinfold freckling usually appears between 3 and 5 yr of age. The frequency of axillary and inguinal freckling is reported to be > 80% by 6 yr of age. (3) Two or more iris Lisch nodules, which are hamartomas located within the iris and are best identified by a slit-lamp examination (Fig. 614.3 ). They are present in more than 74% of patients with NF1. The prevalence of Lisch nodules increases with age, from only 5% of children younger than 3 yr of age, to 42% among children 3-4 yr of age, and virtually 100% of adults older than 21 yr of age. (4) Two or more neurofibromas or one plexiform neurofibroma. Neurofibromas are most visible on the skin, but they may occur on any peripheral nerve in the body, including along peripheral nerves and blood vessels and within viscera, including the gastrointestinal tract. These lesions appear characteristically during adolescence or pregnancy, suggesting a hormonal influence. They are usually small, rubbery lesions with a slight purplish discoloration of the overlying skin. Plexiform neurofibromas are typically congenital and result from diffuse thickening of nerve trunks and surrounding soft tissues. The skin overlying a plexiform neurofibroma may be coarse and associated with hyperpigmentation. Plexiform neurofibromas may produce overgrowth of an extremity and a deformity of the corresponding bone. (5) A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia (which may cause pulsating exophthalmos) or cortical thinning of long bones with or without pseudoarthrosis (most often the tibia). (6) Optic gliomas are present in approximately 15–20% of individuals with NF1; however, only ~ 30% of these are clinically symptomatic and require tumor-directed therapy. They are the most frequently observed CNS tumor in NF1. Because of visual acuity compromise, it is recommended that all children with NF1 undergo at least annual ophthalmologic examinations, or more frequent ones if there is a concern. The most common time to develop symptoms is between the ages of 2-6 yr; they manifest as a change in visual acuity, a change in the visual fields, or pallor of the optic nerve. Extension into the hypothalamus can lead to precocious puberty. The brain MRI findings of an optic glioma include diffuse thickening, localized enlargement, or a distinct focal mass originating from the optic nerve or chiasm (Fig. 614.4 ). (7) A first-degree relative with NF1 whose diagnosis was based on the aforementioned criteria.

Table 614.2

From Marcoux DA, Duran-McKinster C, Baselga E, et al: Pigmentary abnormalities. In Schachner LA, Hansen RC (eds): Pediatric dermatology, 4th ed., Philadelphia, 2011, Mosby, Table 10-2.

Children with NF1 are susceptible to neurologic complications. MRI studies of selected children have shown abnormal hyperintense T2-weighted signals in the optic tracts, brainstem, globus pallidus, thalamus, internal capsule, and cerebellum (Fig. 614.5 ). These signals, unidentified bright objects, tend to disappear with age; most have disappeared by 30 yr of age. It is unclear what the unidentified bright objects represent pathologically, and there is disagreement as to the relationship between the presence and number of unidentified bright objects and the occurrence of learning disabilities, attention-deficit disorders, behavioral and psychosocial problems, and abnormalities of speech among affected children. Therefore, imaging studies such as brain MRIs should be reserved for patients with clinical symptoms only.

One of the most common complications is a learning disability affecting more than half of individuals with NF1. Seizures are observed in approximately 8% of NF1 patients. The cerebral vessels may develop aneurysms or stenosis consistent with moyamoya syndrome (see Chapter 619 ). Neurologic sequelae of these vascular abnormalities include transient cerebrovascular ischemic attacks, hemiparesis, and cognitive defects. Precocious puberty may become evident in the presence or absence of lesions of the optic pathway tumors. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are in the family of aggressive sarcomas and occur either de novo or as the result of malignant degeneration of an existing plexiform neurofibroma. The lifetime risk is 8–13%. Additionally, the incidence of pheochromocytoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leukemia, and Wilms tumor is higher than in the general population. Scoliosis is a common complication found in approximately 10% of the patients. Patients with NF1 are at risk for hypertension, which may be present in isolation or result from renal vascular stenosis or a pheochromocytoma.

Mosaic NF1 (also called segmental NF1 ) has manifestations limited to one or more body segments secondary to somatic (or gonadal) mutations expressed in those locations. Lesions may be unilateral or bilateral, asymmetric or symmetric, and confined to a narrow band or a single quadrant. Neurologic manifestations are rare but have been reported.

Management

Because of the diverse and unpredictable complications associated with NF1, close multidisciplinary follow-up is necessary. Patients with NF1 should have regular clinical assessments at least yearly, focusing the history and examination on the potential problems for which they are at increased risk. These assessments include yearly ophthalmologic examination, neurologic assessment, blood pressure monitoring, and scoliosis evaluation. Neuropsychological and educational testing should be considered as needed. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference has advised against routine imaging studies of the brain and optic tracts because treatment in these asymptomatic NF1 children is rarely required. However, all symptomatic cases (i.e., those with visual disturbance, proptosis, increased intracranial pressure) must be studied without delay. Selumetinib, an oral inhibitor of MAPK kinase 1 and 2, has been demonstrated, in preliminary trials in children with NF1-related inoperable plexiform neurofibromas, to be effective in inducing partial responses and reducing tumor progression.

Genetic Counseling

Although NF1 is an autosomal dominant disorder, more than half the cases are sporadic, representing de novo mutations. The NF1 gene on chromosome region 17q11.2 encodes for a protein also known as neurofibromin. Neurofibromin acts as an inhibitor of the oncogene Ras (Fig. 614.6 ). The diagnosis of NF1 is based on the clinical features. However, molecular testing for the NF1 gene mutations is available and can be useful in a number of cases. Some scenarios in which genetic testing is helpful include patients who meet only one of the criteria for clinical diagnosis, those with unusually severe disease, and those seeking prenatal/preimplantation diagnosis.

NF2 is a less common disorder than NF1; it is also transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner, with an incidence of 1 in 25,000 births. The clinical diagnostic criteria were established by the United States National Institutes of Health consensus conference and modified into the Manchester criteria and the Baser criteria. Diagnosis may also be confirmed by genetic testing from the blood or identical mutation in two separate tumors from the same individual. Typically, NF2 is diagnosed when one of the following four features is present: (1) bilateral vestibular schwannomas; (2) a parent, sibling, or child with NF2 and either unilateral vestibular schwannoma or any two of the following: meningioma, schwannoma, glioma, neurofibroma, or posterior subcapsular lenticular opacities; (3) unilateral vestibular schwannoma and any two of the following: meningioma, schwannoma, glioma, neurofibroma, or posterior subcapsular lenticular opacities; or (4) multiple meningiomas (two or more) and unilateral vestibular schwannoma or any two of the following: schwannoma, glioma, neurofibroma, or cataract. Symptoms of tinnitus, hearing loss, facial weakness, headache, or unsteadiness may appear during childhood, although signs of a cerebellopontine angle mass are more commonly present in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life. CALMs and skin plexiform schwannomas are visible in the pediatric age-group. Posterior subcapsular lens opacities are identified in approximately 50% of patients with NF2 using a slit-lamp examination. The NF2 gene (which codes for a protein known as merlin, or schwannomin) is located on chromosome 22q1.11. Table 614.3 notes the frequency of lesions in NF2.

Table 614.3

Frequency of Lesions Associated With Neurofibromatosis Type 2

| FREQUENCY OF ASSOCIATION WITH NF2 | |

|---|---|

| NEUROLOGIC LESIONS | |

| Bilateral vestibular schwannomas | 90–95% |

| Other cranial nerve schwannomas | 24–51% |

| Intracranial meningiomas | 45–58% |

| Spinal tumors | 63–90% |

| Extramedullary | 55–90% |

| Intramedullary | 18–53% |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Up to 66% |

| OPHTHALMOLOGIC LESIONS | |

| Cataracts | 60–81% |

| Epiretinal membranes | 12–40% |

| Retinal hamartomas | 6–22% |

| CUTANEOUS LESIONS | |

| Skin tumors | 59–68% |

| Skin plaques | 41–48% |

| Subcutaneous tumors | 43–48% |

| Intradermal tumors | Rare |

From Asthagiri AR, Parry DM, Butman JA, et al: Neurofibromatosis type 2, Lancet 373:1974-1984, 2009, Table 1.

Ophthalmologic evaluation, MRI of the brain and spine, audiology, and brainstem-evoked potentials are all important components of the ongoing management of individuals with NF2. Because of the frequency of developing multiple concurrent tumors, intracranial lesions are managed conservatively, with the goal of preserving hearing and maximizing the quality of life.

Schwannomatosis is a form of neurofibromatosis that is clinically distinct from NF1 and NF2 and is characterized by multiple schwannomas in the absence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas. Although the overall incidence is much lower, at 0.47 in 1,000,000 persons, individuals with schwannomatosis are thought to account for 2–10% of all individuals who undergo surgical resection for schwannoma. It is estimated that at least 20% are familial in nature. Diagnosis should be considered in an individual who presents with multiple schwannomas, particularly if there is an affected family member. Evaluation also includes brain and spinal MRI to exclude vestibular and other schwannomas. At any time of presentation, the initial workup must distinguish between NF2 and schwannomatosis. Linkage analysis led to the discovery of the tumor suppressor gene SMARCB1 as the major predisposing gene in schwannomatosis. SMARCB1 , also known as INI1 , is involved in the regulation of the cell cycle, growth, and differentiation. The optimal management and frequency of surveillance imaging have not been established; however, MRI is typically performed yearly.

Legius syndrome (caused by SPRED1 mutations) resembles a mild form of NF1. Patients with Legius syndrome present with multiple CALMs and macrocephaly, with and without skinfold freckling. However, other typical features of NF1, such as Lisch nodules, neurofibromas, optic nerve gliomas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, are not seen with SPRED1 mutations.

Bibliography

Baser ME, R Evans DG, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis 2. Curr Opin Neurol . 2003;16(1):27–33.

Blakeley JO, Evans DG, Adler J, et al. Consensus recommendations for current treatments and accelerating clinical trials for patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. Am J Med Genet A . 2012;158(1):24–41.

Boyd C, Smith MJ, Kluwe L, et al. Alterations in the SMARCB1 (INI1) tumor suppressor gene in familial schwannomatosis. Clin Genet . 2008;74:358–366.

Brems H, Chmara M, Sahbatou M, et al. Germline loss-of-function mutations in SPRED1 cause a neurofibromatosis 1-like phenotype. Nat Genet . 2007;39:1120–1126.

Cnossen MH, de Goede-Bolder A, van den Broek KM, et al. A prospective 10 year follow up study of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch Dis Child . 1998;78:408–412.

DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the national institutes of health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics . 2000;105:608–614.

Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med . 2016;375(26):2550–2560.

Hersh JH. American Academy of pediatrics committee on genetics: health supervision for children with neurofibromatosis. Pediatrics . 2008;121(3):633–642.

Hyman SL, Shores A, North KN. The nature and frequency of cognitive deficits in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Neurology . 2005;65(7):1037–1044.

Isaacs H Jr. Perinatal neurofibromatosis: two case reports and review of the literature. Am J Perinatol . 2010;27:285–292.

Koss M, Scott RM, Irons MB, et al. Moyamoya syndrome associated with neurofibromatosis type 1: perioperative and long-term outcome after surgical revascularization. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2013;11(4):417–425.

Listernick R, Ferner RE, Liu GT, et al. Optic pathway gliomas in neurofibromatosis-1: controversies and recommendations. Ann Neurol . 2007;61(3):189–198.

MacCollin M, Chiocca EA, Evans DG, et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology . 2005;64:1838–1845.

1988. Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National institutes of health consensus development Conference. Arch Neurol . 1988;45:575–578.

Rodriguez D, Young Poussaint T. Neuroimaging findings in neurofibromatosis type 1 and 2. Neuroimaging Clin N Am . 2004;14(2):149–170.

Ruggieri M, Pratico AD. Mosaic neurocutaneous disorders and their causes. Semin Pediatr Neurol . 2015;22:207–233.

Stumpf DA, Alksne JF, Annegers JF, et al. NIH development conference. Neurofibromatosis: Conference statement. Arch Neurol . 1988;45:575–578.

Tuberous Sclerosis

Siddharth Srivastava, Mustafa Sahin

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a multisystem disease characterized by an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, variable expressivity, and a prevalence of 1 in 6,000 to 10,000 newborns. Spontaneous genetic mutations occur in 65% of the cases. Molecular genetic studies have identified two foci for TSC: the TSC1 gene is located on chromosome 9q34, and the TSC2 gene is on chromosome 16p13. The TSC1 gene encodes a protein called hamartin, while the TSC2 gene encodes a protein called tuberin. Within a cell, these two molecules form a complex along with a third protein, TBC1D7 (Tre2-Bub2-Cdc16 1 domain family, member 7). Consequently, a mutation in either the TSC1 gene or the TSC2 gene results in a similar disease in patients, though individuals with TSC2 mutations tend to be more severely affected.

Tuberin and hamartin are involved in a key pathway in the cell that regulates protein synthesis and cell size (see Fig. 614.6 ). One of the ways cells regulate their growth is by controlling the rate of protein synthesis. A protein called mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) is one of the master regulators of cell growth (mTOR has additional roles in the CNS, where it helps regulate neuronal development and synaptic plasticity). mTOR, in turn, is controlled by RHEB (Ras homolog enriched in brain), a small cytoplasmic guanosine triphosphatase. When RHEB is activated, the protein synthesis machinery is turned on, most likely via mTOR signaling, and the cell grows. Under normal conditions, the tuberin/hamartin complex keeps RHEB in an inactive state. However, in TSC, there is disinhibition of RHEB and subsequent overactivation of the mTOR pathway. Accordingly, the TSC1 and TSC2 genes can be considered tumor-suppressor genes. The loss of either tuberin or hamartin protein results in the formation of numerous benign tumors (hamartomas).

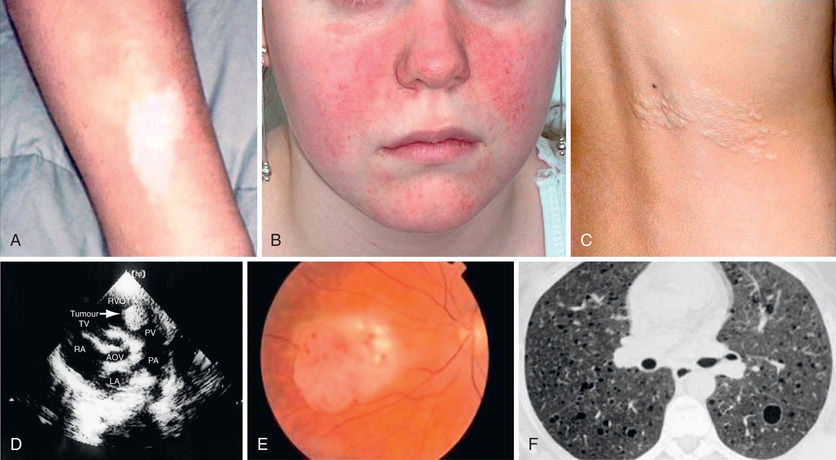

TSC is an extremely heterogeneous disease with a wide clinical spectrum varying from severe intellectual disability and intractable epilepsy to normal intelligence and a lack of seizures. This variation is often seen within the same family, that is, with individuals carrying the same mutation. The disease affects many organ systems other than the skin and brain, including the heart, kidney, eyes, lungs, and bone (Fig. 614.7 ).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Definite TSC is diagnosed when at least two major or one major plus two minor features are present (Tables 614.4 and 614.5 list the major and minor features). In addition, carrying a pathogenic mutation in TSC1 or TSC2 is sufficient for the diagnosis of TSC.

Table 614.4

Table 614.5

| Dental enamel pits (>3) |

| Intraoral fibromas (≥2) |

| Retinal achromic patch |

| Confetti skin lesions |

| Nonrenal hamartomas |

| Multiple renal cysts |

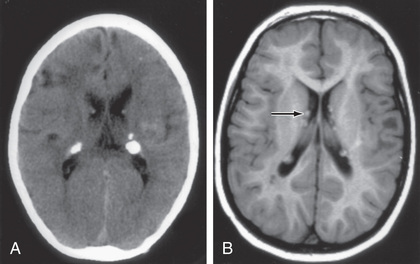

The hallmark of TSC is the involvement of the CNS. Retinal lesions consist of two types: hamartomas (elevated mulberry lesions or plaque-like lesions (Fig. 614.8 ) and white depigmented patches (similar to the hypopigmented skin lesions). The characteristic brain lesion is a cortical tuber (Fig. 614.9 ). Brain MRI is the best way of identifying cortical tubers, which can form before birth.

Subependymal nodules are lesions found along the wall of the lateral ventricles, where they undergo calcification and project into the ventricular cavity, producing a candle-dripping appearance. These lesions do not cause any problems; however, in 5–10% of cases, these benign lesions can grow into subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs). These tumors can grow and block the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid around the brain and cause hydrocephalus, which requires immediate neurosurgical intervention. Thus, it is recommended that all asymptomatic TSC patients undergo brain MRI every 1-3 yr to monitor for new occurrences of SEGA. Patients with large or growing SEGAs, or with SEGAs causing ventricular enlargement without other manifestations, should undergo MRI scans more frequently, and the patients and their families should be educated regarding the potential of new symptoms due to increased intracranial pressure. Surgical resection should be performed for acutely symptomatic SEGA. For growing but otherwise asymptomatic SEGAs, either surgical resection or medical treatment with an mTOR inhibitor (everolimus) may be used. Treatment with everolimus can be effective in slowing the growth or even reducing the size of SEGAs. Everolimus is also effective in treating renal angiomyolipomas, and sirolimus, another mTOR inhibitor, is approved for lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

The most common neurologic manifestations of TSC consist of epilepsy, cognitive impairment, and autism spectrum disorder. TSC may present during infancy with infantile spasms and a hypsarrhythmic electroencephalogram pattern. However, it is important to remember that TSC patients can have infantile spasms without hypsarrhythmia. The seizures may be difficult to control, and at a later age, they may develop into focal-onset seizures or generalized myoclonic seizures (see Chapter 611 ). Vigabatrin is the first-line therapy for infantile spasms. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) can be used if treatment with vigabatrin fails. Anticonvulsant therapy for other seizure types in TSC should generally follow that of other epilepsies, and epilepsy surgery should be considered for medically refractory TSC patients. Everolimus (adjunctive) has been effective therapy for reducing the number of seizures in patients with treatment-refractory seizures. In addition to epilepsy, about 90% of individuals with TSC have a spectrum of cognitive, behavioral, psychiatric, and academic impairments termed tuberous sclerosis–associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND), which include intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, and depression. About 45% of individuals with TSC have intellectual disability, and up to 50% have autism spectrum disorder.

Skin Lesions

More than 90% of patients show the typical hypomelanotic macules that have been likened to an ash leaf on the trunk and extremities. Visualization of the hypomelanotic macule is enhanced by the use of a Wood ultraviolet lamp (see Chapter 672 ). To count as a major feature, at least three hypomelanotic macules must be present (see Fig. 614.7 ). Facial angiofibromas develop between 4 and 6 yr of age; they appear as tiny red nodules over the nose and cheeks and are sometimes confused with acne (see Fig. 614.7 ). Later, they enlarge, coalesce, and assume a fleshy appearance. A shagreen patch is also characteristic of TSC and consists of a roughened, raised lesion with an orange-peel consistency located primarily in the lumbosacral region (see Fig. 614.7 ). Forehead fibrous plaques usually occur on one side of the forehead. They are characteristically raised, yellow-brown or flesh-colored, and soft-to-hard in consistency. Forehead plaques are histologically similar to facial angiofibromas, though the former can appear at any time point. During adolescence or later, small fibromas or nodules of skin may form around fingernails or toenails in 15–20% of TSC patients (Fig. 614.10 ).

Other Organ Involvement

Approximately 50% of children with TSC have cardiac rhabdomyomas, which may be detected in the fetus by an echocardiogram, usually by 20-30 wk gestation. The rhabdomyomas may be numerous and located throughout the ventricular myocardium, and although they can cause congestive heart failure and arrhythmias in a minority of patients, they tend to slowly resolve spontaneously. In 75–80% of patients older than 10 yr of age, the kidneys display angiomyolipomas that are usually benign tumors. Angiomyolipomas begin in childhood in many individuals with TSC, but they may not be problematic until young adulthood. By the 3rd decade of life, they may cause lumbar pain and hematuria from slow bleeding, and rarely they may result in sudden retroperitoneal bleeding. Embolization followed by corticosteroids to alleviate postembolization syndrome is first-line therapy for angiomyolipoma presenting with acute hemorrhage. Nephrectomy should be avoided as a way of maintaining renal function, because lesions can be numerous and bilateral. For asymptomatic, growing angiomyolipomas measuring larger than 3 cm in diameter, an mTOR inhibitor, everolimus, is approved for treatment by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Selective embolization or kidney-sparing resection is an alternative therapy for asymptomatic angiomyolipoma. Single or multiple renal cysts are also commonly present in TSC; renal cell carcinoma, on the other hand, is rare. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is the classic pulmonary lesion in TSC and only affects women, beginning in late adolescence (≥15 yr). Rapamycin is approved by the U.S. FDA for lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Diagnosis of TSC relies on a high index of suspicion when assessing a child with infantile spasms. A careful evaluation for the typical skin and retinal lesions should be completed in all patients with a seizure disorder or autism spectrum disorder. Brain MRI confirms the clinical diagnosis in most cases. Genetic testing for TSC1 and TSC2 mutations is available and should be considered when the individual patient does not meet all the clinical criteria, or in order to provide molecular confirmation of a clinical diagnosis. Prenatal testing may be offered when a known TSC1/2 mutation exists in that family.

Management

As for routine follow-up of individuals with TSC, the following are recommended in addition to physical examination: brain MRI every 1-3 yr, renal imaging using ultrasound, CT or MRI every 1-3 yr; echocardiogram every 1-3 yr in patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas; electrocardiogram every 3-5 yr; high-resolution chest CT every 5-10 yr in females older than 18 yr; dental examination twice a year; skin examinations once a year; detailed ophthalmic examination once a year in patients with vision concerns or retinal lesions (sooner if they are receiving treatment with vigabatrin); neurodevelopmental testing at the time of beginning 1st grade; and screening for TAND at each clinic visit. Based on the complications of the disease, additional follow-up testing may be required for each individual. Symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure suggest obstruction of the foramen of Monro by a SEGA and warrant immediate investigation and surgical intervention.

Bibliography

Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIT-2): a multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet . 2013;381:817–824.

Cardamore M, Flanagan D, Mowat D, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors for intractable epilepsy and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Pediatr . 2014;164:1105–1200.

Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med . 2006;355:1345–1356.

Cudzilo CJ, Szczesniak RD, Brody AS, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis screening in women with tuberous sclerosis. Chest . 2013;144:578–585.

Curatolo P, Franz DN, Lawson JA, et al. Adjunctive everolimus for children and adolescents with treatment refractory seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis complex: post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 EXIST-3 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health . 2018;2:495–504.

de Vries PJ, Whittemore VH, Leclezio L, et al. Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND) and the TAND checklist. Pediatr Neurol . 2015;52:25–35.

Datta AN, Hahn CD, Sahin M. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex in infancy. J Child Neurol . 2008;23:268–273.

Ewalt DH, Diamond N, Rees C, et al. Long-term outcome of transcatheter embolization of renal angiomyolipomas due to tuberous sclerosis complex. J Urol . 2005;174(5):1764–1766.

Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicenter, randomizes, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet . 2013;381:125–132.

Kingswood JC, Bissler JJ, Budde K, et al. Review of the tuberous sclerosis renal guidelines from the 2012 consensus Conference: current data and future study. Nephron . 2016;134:51–58.

Lai J, Modi L, Ramai D, Tortora M. Tuberious sclerosis complex and polycystic kidney disease contiguous gene syndrome with moyamoya disease. Pathol Res Pract . 2017;213:410–415.

Siroky BJ, Towbin AJ, Trout AT, et al. Improvement in renal cystic disease of tuberous sclerosis complex after treatment with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor. J Pediatr . 2017;187:318–322.

Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Margossian R, et al. Association between cardiac tumors and tuberous sclerosis in the fetus and neonate. Am J Cardiol . 2003;92(4):487–489.

Warncke JC, Brodie KE, Grantham EC, et al. Pediatric renal angiomyolipomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Urol . 2017;197:500–506.

Sturge-Weber Syndrome

Anna Pinto

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a segmental vascular neurocutaneous disorder with a constellation of symptoms and signs characterized by capillary malformation in the face (port-wine birthmark) and brain (leptomeninges), as well as abnormal blood vessels of the eye leading to glaucoma. Patients present with seizures, hemiparesis, stroke-like episodes, headaches, and developmental delay. Approximately 1 in 20,000 to 50,000 live births are affected with SWS.

Etiology

The sporadic incidence and focal nature of SWS suggests the presence of somatic mutations. Whole-genome sequencing from affected and unaffected skin of three patients with SWS identified a single-nucleotide variant (c.548G→A, p.Arg183Gln) in the GNAQ gene (see Fig. 614.6 ). Others have confirmed this mutation in samples of affected tissue from 88% of SWS patients (23 of 26) from a larger cohort, as well as from 92% of participants (12 of 13) with apparently nonsyndromic port-wine birthmarks (PWBs). Brain tissue from SWS patients also demonstrates the same change in the GNAQ gene. These results strongly suggest that SWS occurs as a result of mosaic mutations in GNAQ .

The GNAQ p.R183Q mutation is enriched in endothelial cells in SWS brain lesions, thereby revealing endothelial cells as a source of aberrant Gαq signaling. The timing of the somatic mutation in GNAQ during development likely affects the clinical phenotype. Low flow of the leptomeningeal capillary malformation appears to result in a chronic hypoxic state leading to cortical atrophy and calcifications.

Clinical Manifestations

Facial PWBs are present at birth, but not all are associated with SWS (Table 614.6 ). In fact, the overall incidence of SWS has been reported to be 20–50% in those with a PWB involving the forehead and upper eyelid. The PWB tends to be unilateral, and ipsilateral to the brain involvement (Fig. 614.11 ). The capillary malformation may also be evident over the lower face and trunk and in the mucosa of the mouth and pharynx. Buphthalmos and glaucoma of the ipsilateral eye are common complications. Seizures occur in 75–80% of all SWS patients and in over 90% of those with bilateral brain involvement. Early onset of seizures will likely occur during the 1st yr of life but rarely during the 1st mo of life, and they are typically focal clonic and contralateral to the side of the facial capillary malformation. They may become refractory to anticonvulsants, and status epilepticus is often associated. One third of children with intractable epilepsy associated with SWS experience episodes of prolonged postictal deficits, which would last from 1 day to a few years, until recovering back to baseline. Some patients also develop slowly progressive hemiparesis. Transient stroke-like episodes or visual defects persisting for several days and unrelated to seizure activity are common and probably result from thrombosis of cortical veins in the affected region. Although neurodevelopment appears to be normal in the first year of life, intellectual disability or severe learning disabilities are present in at least 50% of patients in later childhood, probably the result of intractable epilepsy and increasing cerebral atrophy. The degree of visual field, hemiparesis, seizure frequency, and cognitive function (based on age-group: infant/preschooler, child, and adult) can be rated using a validated SWS neurologic rating system.

Table 614.6

CLOVES, Congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi, and scoliosis/skeletal and spinal anomalies.

From Paller AS, Mancini (eds): Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology, 5th ed., Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Box 12-2.

Diagnosis

Brain MRI with contrast is the imaging modality of choice for demonstrating the extension of pial capillary malformation in SWS (Fig. 614.12 ). White matter abnormalities are common and are thought to be a result of chronic hypoxia. Often, atrophy is noted ipsilateral to the leptomeningeal capillary malformation. Calcifications can be seen best with a head CT (Fig. 614.13 ). The choroid plexus is frequently enlarged, and the degree of plexal enlargement shows a positive correlation with the extent of the leptomeningeal capillary malformation. Positron emission tomography using 18 F-deoxyglucose has been used to study cerebral metabolism in patients with SWS, and it has been useful for the surgical planning and prognosis. Ophthalmologic evaluation examining for glaucoma is also necessary and is a lifelong concern because ocular complications can occur at any moment during a lifetime. Based on the involvement of the brain and the face, there are three types of SWS in the Roach Scale:

- Type I—Both facial and leptomeningeal angiomas present; may have glaucoma.

- Type II—Facial angioma alone (no CNS involvement); may have glaucoma.

- Type III—Isolated leptomeningeal angiomas; usually no glaucoma.

In addition, there is an overlap syndrome between SWS and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (mixed capillary, venous, or lymphatic malformations involving bone and muscle in one limb).

Management

The management of SWS is symptomatic and multidisciplinary but not well studied by prospective studies. Discovery of the causative somatic mosaic mutation suggests new insights into the pathophysiology of this vascular malformation disorder and potential novel treatment strategies for future study. Treatment is aimed at seizure control, relief of headaches, and prevention of stroke-like episodes, as well as monitoring of glaucoma and laser therapy for the cutaneous capillary malformations. Seizures beginning in infancy are not always associated with a poor neurodevelopmental outcome. For patients with well-controlled seizures and normal or near-normal development, management consists of anticonvulsants and surveillance for complications, including glaucoma, buphthalmos, and behavioral abnormalities. If the seizures are refractory to anticonvulsant therapy, especially in infancy and the first 1 to 2 yr, and arise from primarily one hemisphere, most medical centers advise a hemispherectomy. The use of low-dose aspirin is still controversial. The medication is not used routinely, but patients with stroke-like events and frequent refractory seizures may benefit from this form of treatment. Because of the risk of glaucoma, regular measurement of intraocular pressure is indicated. The facial PWB is often a target of ridicule by classmates, leading to psychological trauma. Pulsed-dye laser therapy often provides excellent clearing of the PWB, particularly if it is located on the forehead.

Bibliography

Comi AM. Advances in Sturge-weber syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol . 2006;19(2):124–128.

Dymerska M, Kirkorian AY, Offerman EA, et al. Size of facial port-wine birthmark may predict neurologic outcome in Sturge-weber syndrome. J Pediatr . 2017;188:205–209.

Huang L, Couto JA, Pinto A, et al. Somatic GNAQ mutation is enriched in brain endothelial cells in Sturge-weber syndrome. Pediatr Neurol . 2017;67:59–63.

Kossoff EH, Buck C, Freeman JM. Outcomes of 32 hemispherectomies for Sturge-weber syndrome worldwide. Neurology . 2002;59:1735–1738.

Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med . 2013;368(21):1971–1979.

Tan OT, Sherwood K, Gilchrest BA. Treatment of children with port-wine stains using the flashlamp-pulsed tunable dye laser. N Engl J Med . 1989;320:416–421.

Von Hippel-Lindau Disease

Siddharth Srivastava, Mustafa Sahin

von Hippel–Lindau disease affects many organs, including the cerebellum, spinal cord, retina, kidney, pancreas, and epididymis. Its incidence is around 1 in 36,000 newborns. It results from an autosomal dominant mutation affecting a tumor suppressor gene, VHL. Approximately 80% of individuals with von Hippel–Lindau syndrome have an affected parent, and approximately 20% have a de novo gene mutation. Molecular testing is available and detects mutations in almost 100% of probands.

The major neurologic features of the condition include cerebellar hemangioblastomas and retinal angiomas (also known as retinal capillary hemangioblastomas). Patients with cerebellar hemangioblastoma present in early adult life with symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure. A smaller number of patients have hemangioblastoma of the spinal cord, producing abnormalities of proprioception and disturbances of gait and bladder function. A brain CT or MRI scan typically shows a cystic cerebellar lesion with a vascular mural nodule. Total surgical removal of the tumor is curative.

Approximately 25% of patients with cerebellar hemangioblastoma have retinal angiomas. Retinal angiomas are characterized by small masses of thin-walled capillaries that are fed by large and tortuous arterioles and venules. They are usually located in the peripheral retina so that vision is unaffected. Exudation in the region of the angiomas may lead to retinal detachment and visual loss. Retinal angiomas are treated with photocoagulation and cryocoagulation, and both have produced good results, though complications such as retinal edema can occur.

Cystic lesions of the kidneys, pancreas, liver, and epididymis, as well as pheochromocytoma, are frequently associated with von Hippel–Lindau disease. Renal carcinoma is the most common cause of death, and CNS hemangioblastomas also contribute to morbidity. Regular follow-up and appropriate imaging studies are necessary to identify lesions that may be treated at an early stage. In affected individuals 1 yr and older, there should be a yearly assessment of neurologic status, vision/ophthalmologic status, hearing, and blood pressure. After age 5 yr, there should be laboratory screening for pheochromocytoma every year, hearing evaluation every 2-3 yr, and contrast-enhanced MRI with thin cuts of the internal auditory canal to evaluate for endolymphatic sac tumors in those who are symptomatic. After age 16 yr, there should be abdominal ultrasound yearly to identify visceral lesions, and MRI of the abdomen and entire neural axis every 2 yr.

Bibliography

Latif F, Tory K, Gmarra J, et al. Identification of the von Hippel-lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science . 1993;260:1317–1320.

Maher ER, Kaelin WG Jr. Von Hippel-lindau disease. Medicine (Baltimore) . 1997;76:381–391.

Maher ER, Neumann HP, Richard S. Von Hippel-lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet . 2011;19:617–623.

Linear Nevus Sebaceous Syndrome

Siddharth Srivastava, Mustafa Sahin

This sporadic condition is characterized by a large facial nevus, neurodevelopmental abnormalities, and systemic defects. The nevus is usually located on the forehead and nose and tends to be midline in its distribution. It may be quite faint during infancy but later becomes hyperkeratotic, with a yellow-brown appearance. Two thirds of the patients with linear nevus syndrome demonstrate associated neurologic findings, including cortical dysplasia, glial hamartomas, and low-grade gliomas. Cerebral and cranial anomalies, predominantly hemimegalencephaly and enlargement of the lateral ventricles, are reported in 72% of cases. The incidence of epilepsy and intellectual disability is as high as 75% and 60%, respectively. Focal neurologic signs, including hemiparesis and homonymous hemianopia, may occur. Other organ systems may be involved, including the eyes (strabismus, retinal abnormalities, coloboma, cataracts, corneal revascularization, and ocular hemangiomas), heart (aortic coarctation), kidneys (horseshoe kidney), and skeleton (fibrous dysplasia, skeletal hypoplasia, and scoliosis/kyphoscoliosis). The syndrome is associated with somatic mutations in members of the Ras family of oncogenes, including HRAS (HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase), KRAS (KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase), and NRAS (neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog) (see Fig. 614.6 ).

PHACE Syndrome

Siddharth Srivastava, Mustafa Sahin

See also Chapter 669 .

The syndrome denotes p osterior fossa malformations, h emangiomas, a rterial anomalies, c oarctation of the aorta and other cardiac defects, and e ye abnormalities. It is also referred to as PHACES syndrome when ventral developmental defects, including s ternal clefting and/or a s upraumbilical raphe, are present. Large facial hemangiomas may be associated with a Dandy-Walker malformation, vascular anomalies (such as coarctation of aorta, aplasia or hypoplastic carotid arteries, aneurysmal carotid dilation, and aberrant left subclavian artery), persistent fetal vasculature, morning glory disc anomaly, glaucoma, cataracts, microphthalmia, optic nerve hypoplasia, and ventral defects (sternal clefts). Endocrinopathies (such as hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, and diabetes insipidus) can also occur. The facial hemangioma is typically ipsilateral to the aortic arch. The Dandy-Walker malformation is the most common developmental abnormality of the brain. Other anomalies include hypoplasia or agenesis of the cerebellum, cerebellar vermis, corpus callosum, cerebrum, and septum pellucidum. Cerebrovascular anomalies can result in acquired, progressive vessel stenosis and acute ischemic stroke. According to a case series of 29 children with PHACE syndrome, 69% had abnormal neurodevelopment, including 44% with language delay, 36% with gross motor delay, and 8% with fine motor delay. Over half (52%) had neurologic exam abnormalities, the most common of which was abnormal speech (such as dysarthria or aphasia). Overall, there is a female predominance. The underlying pathogenesis of PHACE syndrome remains unknown, though evidence that infantile hemangiomas may result from abnormal growth and differentiation of hemogenic endothelium highlights some avenues for further investigation. Due to the involvement of multiple organ systems in PHACE syndrome, clinical care should require multidisciplinary input. The beta-blocker propranolol is emerging as a treatment for infantile hemangiomas associated with PHACE syndrome.

LUMBAR syndrome (l ower-segment hemangioma, u rogenital defects, m yelopathy of spinal cord, b ony deformities, a rterial and anorectal defects, r enal anomalies), also called SACRAL syndrome (s pinal dysraphism, a nogenital anomalies, c utaneous anomalies, r enal-urologic anomalies, a ngioma of l umbosacral localization), is a possible variant of PHACES syndrome in the lumbosacral region.

Bibliography

Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL, et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics . 2013;131:128–140.

Metry DW, Dowd CF, Barkovich AJ, et al. The many faces of PHACE syndrome. J Pediatr . 2001;139:117–123.

Poetke M, Frommeld T, Berlien HP. PHACE syndrome: new views on diagnostic criteria. Eur J Pediatr Surg . 2002;12:366–374.

Tangtiphaiboontana J, Hess CP, Bayer M, et al. Neurodevelopmental abnormalities in children with PHACE syndrome. J Child Neurol . 2013;28:608–614.

Winter PR, Itinteang T, Leadbitter P, Tan ST. PHACE syndrome–clinical features, aetiology and management. Acta Paediatr . 2016;105:145–153.

Incontinentia Pigmenti

Siddharth Srivastava, Mustafa Sahin

Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) is a rare, heritable, multisystem ectodermal disorder that features dermatologic, dental, ocular, and CNS abnormalities. The phenotype is produced by defects in the X-linked dominant gene IKBKG (inhibitor of kappa B kinase gamma, previously NEMO) , which plays a role in activating the anti-apoptotic signaling molecule NF-kappaB (NF-κB). In the majority of males, IP causes embryonic lethality owing to increased vulnerability to cell death, so those who survive may have somatic mosaicism for a pathogenic IKBKG variant or a 47,XXY karyotype. Among affected females, an abnormal gene product causes apoptosis in cells; therefore, highly skewed X-inactivation can be a result. The paucity of affected males, the occurrence of female-to-female transmission, and an increased frequency of spontaneous abortions in carrier females support this supposition.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

This disease has four stages, not all of which may occur in a given patient. The 1st (bullous) stage is evident at birth or in the first few weeks of life and consists of erythematous linear streaks and plaques of vesicles (Fig. 614.14 ) that are most pronounced on the limbs and circumferentially on the trunk. The lesions may be confused with those of herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, or mastocytosis, but the linear configuration is unique. Histopathologically, epidermal edema and eosinophil-filled intraepidermal vesicles are present. Eosinophils also infiltrate the adjacent epidermis and dermis. Blood eosinophilia as high as 65% of the white blood cell count is common. The 1st stage generally resolves by 4 mo of age, but mild, short-lived recurrences of blisters may develop during febrile illnesses. In the 2nd (verrucous) stage, as blisters on the distal limbs resolve, they become dry and hyperkeratotic, forming verrucous plaques. The verrucous plaques rarely affect the trunk or face and generally involute within 6 mo. Epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis, dyskeratosis, and papillomatosis are characteristic. The 3rd (pigmentary) stage is the hallmark of incontinentia pigmenti. It generally develops over weeks to months and may overlap the earlier phases or, more commonly, begin to appear in the 1st few mo of life. Hyperpigmentation is more often apparent on the trunk than the limbs and is distributed in macular whorls, reticulated patches, flecks, and linear streaks that follow Blaschko lines. The axillae and groin are characteristically affected. The sites of involvement are not necessarily those of the preceding vesicular and warty lesions. The pigmented lesions, once present, persist throughout childhood. They generally begin to fade by early adolescence and often disappear by age 16 yr. Occasionally, the pigmentation remains permanently, particularly in the groin. The lesion, histopathologically, shows vacuolar degeneration of the epidermal basal cells and melanin in melanophages of the upper dermis as a result of incontinence of pigment. In the 4th (atretic) stage, hairless, anhidrotic, hypopigmented patches or streaks occur as a late manifestation of incontinentia pigmenti; they may develop, however, before the hyperpigmentation of stage 3 has resolved. The lesions develop mainly on the flexor aspect of the lower legs and less often on the arms and trunk. On histology, there are decreased rete ridges (epidermal protrusions) and sweat gland secretory coils during this stage.

Approximately 80% of affected children have other defects. Alopecia, which may be scarring and patchy or diffuse, is most common on the vertex and occurs in up to 40% of patients. Hair may be lusterless, wiry, and coarse. Dental anomalies, which are present in up to 80% of patients and are persistent throughout life, consist of late dentition, hypodontia, conical teeth, malocclusion, and impaction. CNS manifestations, including seizures, intellectual disability, hemiplegia, hemiparesis, spasticity, microcephaly, and cerebellar ataxia, are found in up to 30% of affected children. Ocular anomalies, such as retinal neovascularization, microphthalmos, strabismus, optic nerve atrophy, cataracts, and retrolenticular masses, occur in > 30% of children. Nonetheless, > 90% of patients have normal vision. Notably, retinal neovascularization could herald abnormalities in the CNS vasculature that predispose the patient to ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Less common abnormalities include dystrophy of nails (ridging, pitting), subungual and periungual keratotic tumors, and skeletal defects.

Diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti is made on clinical grounds, although major and minor criteria have been established to aid in the diagnosis. Satisfaction of at least one of the major criteria is needed for a clinical diagnosis; lack of fulfillment of any of the minor criteria should direct the clinician toward the possibility of another diagnosis. Wood's lamp examination may be useful in older children and adolescents to highlight pigmentary abnormalities. Clinical molecular testing is available, and around 65% of affected females and 16% of affected males have an 11.7-kb common deletion in IKBKG that removes exons 4 through 10. Skin biopsy may be helpful if the patient has unclear clinical findings and negative genetic testing. For male patients with negative genetic testing from blood, a mutation may be detectable in skin cells from an affected region, increasing the utility of a skin biopsy. The differential diagnosis includes hypomelanosis of Ito, which presents with similar skin manifestations and is often associated with chromosomal mosaicism.

Management

The choice of investigative studies and the plan of management depend on the occurrence of particular noncutaneous abnormalities because the skin lesions are benign. Dermatology may be involved to characterize the nature of skin lesions, as well as to manage skin manifestations that are extensive. Medical genetics and genetic counseling can help establish a molecular diagnosis in addition to providing family counseling. Ophthalmology is important for delineating the presence and extent of retinal neovascularization (which can be treated with cryotherapy and laser photocoagulation) and other ocular abnormalities. Neurology can help evaluate and treat relevant concerns such as microcephaly, seizures, and motor abnormalities. A brain MRI is useful if there is a neurologic deficit or retinal neovascularization. Dentistry can provide teeth implants along with routine care. If dental abnormalities affect speech or feeding, then input from speech pathologists and nutritionists may be necessary. Finally, developmental medicine can formulate recommendations regarding developmental and behavioral concerns.

Bibliography

Bruckner AL. Incontinentia pigmenti: a window to the role of NF-kappaB function. Semin Cutan Med Surg . 2004;23:116–124.

Meuwissen ME, Mancini GM. Neurological findings in incontinentia pigmenti; a review. Eur J Med Genet . 2012;55:323–331.

Minić S, Trpinac D, Obradović M. Systematic review of central nervous system anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti. Orphanet J Rare Dis . 2013;8:25.

Santa-Maria FD, Mariath LM, Poziomczyk CS, et al. Dental anomalies in 14 patients with IP: clinical and radiological analysis and review. Clin Oral Investig . 2017;21(5):1845–1852.

Smahi A, Courtois G, Vabres P, et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The international incontinentia pigmenti (IP) consortium. Nature . 2000;405:466–472.