Brain Abscess

Andrew B. Janowski, David A. Hunstad

The incidence of brain abscess is between 0.3 and 1.3 cases per 100,000 people per year. Development of brain abscess is most often associated with an underlying etiology, including: contiguous spread from an associated infection (meningitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, sinusitis, soft tissue infection of the face or scalp, orbital cellulitis, or dental infections); direct compromise of the blood–brain barrier due to penetrating head injuries or surgical procedures; embolic phenomena (endocarditis); right-to-left shunts (congenital heart disease or pulmonary arteriovenous malformation); immunodeficiency; or infection of foreign material inserted into the central nervous system (CNS), including ventriculoperitoneal shunts.

Pathology

Cerebral abscesses occur in both hemispheres in children, but in adults, left-sided abscesses are more common, likely due to penetrating injuries from right-handed assailants. Nearly 80% of abscesses occur in the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes, while abscesses in the occipital lobe, cerebellum, and brainstem account for the remainder of cases. In 18% of cases, multiple brain abscesses are present, and in nearly 20% of cases, no predisposing risk factor can be identified. Abscesses in the frontal lobe are often caused by extension from sinusitis or orbital cellulitis, whereas abscesses located in the temporal lobe or cerebellum are frequently associated with otitis media and mastoiditis.

Etiology

The predominant organisms that cause brain abscesses are streptococci, which account for one third of all cases in children, with members of the Streptococcus anginosus group (S. anginosus, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus intermedius) being the most common streptococci. Other important streptococci include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus spp., and other viridans streptococci. Staphylococcus aureus is the second most common organism in pediatric brain abscesses, accounting for 11% of cases, and is most often associated with penetrating injuries. Other bacteria isolated from brain abscesses include Gram-negative aerobic organisms (Haemophilus spp., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus spp., and other Enterobacteriaceae) and anaerobic bacteria (Gram-positive spp., Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., Prevotella spp., and Actinomyces spp.). In neonates with meningitis, abscess formation is a complication in 13% of cases, with Citrobacter koseri, Cronobacter sakazakii, Serratia marcescens, and Proteus mirabilis being special considerations in this age-group. In up to 27% of cases, more than one organism is cultured. Abscesses associated with mucosal infections (sinusitis or dental infections) frequently are polymicrobial and include anaerobic organisms. Atypical bacteria, including Nocardia, Mycobacterium, and Listeria spp., and fungi (Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptococcus) are more common in children with impaired host defenses.

Clinical Manifestations

Often the early stages of cerebritis and abscess formation are asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific symptoms, including low-grade fever, headache, and lethargy. As the inflammatory process proceeds, vomiting, severe headache, seizures, papilledema, focal neurologic signs (hemiparesis), and coma may develop. A cerebellar abscess is characterized by nystagmus, ipsilateral ataxia and dysmetria, vomiting, and headache. If the abscess ruptures into the ventricular cavity, overwhelming shock and death occur in 27–85% of cases.

Diagnosis

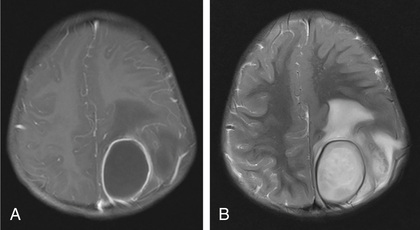

The key to diagnosis of brain abscesses is prompt imaging of the CNS. Brain MRI with contrast is the diagnostic test of choice because it can aid in differentiating abscesses from cysts and necrotic tumors (Fig. 622.1 ). As an alternative, cranial CT can provide more rapid imaging results but cannot provide the fine tissue detail offered by MRI (Fig. 622.2 ). Both MRI and CT scans with contrast can demonstrate a ring-enhancing abscess cavity. The CT findings of cerebritis are characterized by a parenchymal low-density lesion, whereas T2-weighted MRI images feature increased signal intensity. Other abnormalities in common laboratory tests can be observed in children with brain abscesses. The peripheral white blood cell count is elevated in 60% of cases, and blood cultures are positive in 28% of cases. Lumbar puncture is not routinely recommended in cases of brain abscesses, because the procedure could cause brain herniation from elevated intracranial pressure. When tested, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is normal in 16% of cases, 71% of cases exhibit CSF pleocytosis, and 58% will have an elevated CSF protein level. CSF cultures are positive in only 24% of cases; therefore, a culture obtained from the abscess fluid is essential for identifying bacterial pathogens. In some cases, culture of the abscess fluid can be sterile, and alternative testing including 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing may be used to identify organisms. An electroencephalogram (EEG) may identify corresponding focal slowing.

Treatment

The initial management of a brain abscess includes prompt diagnosis and initiation of an antibiotic regimen that is based on the most likely pathogens. Empiric therapy consists of a combination of a 3rd-generation cephalosporin and metronidazole, often with vancomycin to provide coverage of methicillin-resistant S. aureus and cephalosporin-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae. If resistant Gram-negative organisms are suspected, as in cases of infected ventriculoperitoneal shunts, cefepime or meropenem may be used as the β-lactam in the initial regimen. Listeria monocytogenes may cause a brain abscess in the neonate and if suspected, penicillin G or ampicillin with gentamicin is recommended. In immunocompromised patients, broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage is used, and amphotericin B therapy should be considered for activity against fungi.

Neurosurgical procedures for brain abscess have been greatly enhanced by stereotactic MRI or CT systems, allowing for optimized approaches to minimize morbidity. Aspiration of the abscess is recommended for diagnostic cultures and decompression unless contraindicated based on the location or the patient's condition. There are limited data regarding injection of antibiotics into the abscess cavity, and this technique is not routinely recommended. Small abscesses under 2.5 cm in diameter or multiple abscesses may be treated with antibiotics in the absence of drainage, with follow-up neuroimaging studies to ensure a decrease in abscess size. Surgical excision of an abscess is rarely required, because such a procedure may be associated with greater morbidity compared with aspiration of a cavity. Administration of glucocorticoids can reduce edema, though evidence for improved outcomes with steroids is lacking.

The antibiotic regimen may be narrowed or made more specific once abscess culture data are available, though most abscesses are polymicrobial and not all organisms present may be isolated in culture. The duration of parenteral antibiotic therapy depends on the organism and response to treatment but is most typically 6 wk.

Prognosis

Mortality rates prior to the 1980s ranged from 11–53%. More recent mortality rates accompanying wider use of CT and MRI, improved microbiologic techniques, and prompt antibiotic and surgical management, range from 5–10%. Factors associated with high mortality rates at the time of admission include delayed administration of antimicrobials, age < 1 yr, multiple abscesses, and coma. Long-term sequelae occur in about one third of the survivors and include hemiparesis, seizures, hydrocephalus, cranial nerve abnormalities, and behavioral and learning difficulties.