Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (Pseudotumor Cerebri)

Alasdair P.J. Parker

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), or pseudotumor cerebri, is frequently considered a potential cause of headache with papilledema in children with normal standard findings on brain MRI. A false-positive diagnosis is common, and outlined below are strategies to avoid it. The pathophysiology is poorly understood, and no randomized controlled trial exists regarding treatment strategies in children.

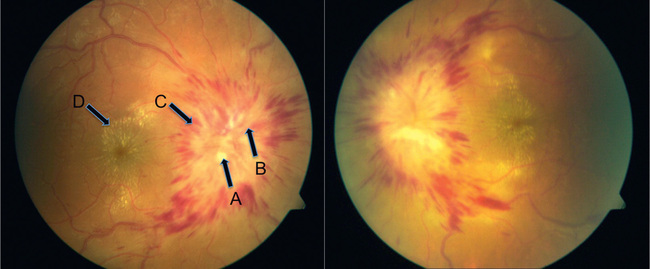

IIH is rare, but an accurate diagnosis is essential because of the risk of visual failure. There has been an evolution in the investigation of this condition. Previously, normal levels of intracranial pressure (ICP) were unclear, leading to overdiagnosis of IIH. Now, studies in children with ICP monitoring show an upper limit of normal as 10 mm Hg (13.5 cm H2 O) between the ages of 2 and 5 yr, with the adult level of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure being reached by 8 yr of age. Currently, the 90th percentile of CSF pressure on lumbar puncture has been reported to be 28 cm CSF (22 mm Hg) in children age 1 to 18 yr, without a significant age effect. Other normal parameters include CSF cell count, protein content, and ventricular size, although the ventricular size on brain MRI could be slightly decreased. Papilledema is almost universally present, and in rare cases where it is not, great care should be taken before the diagnosis, as there is a high rate of misdiagnosis (Fig. 623.1 ).

Etiology

IIH, by definition, will not have an identifiable cause, despite typical findings. A large proportion of children referred to the pediatrician with possible/probable IIH after a thorough history, examination, and careful investigation will have secondary IH with an underlying cause identified. Table 623.1 lists some of the many disorders that cause IH with no obstructive lesion on MRI, including venous obstruction; metabolic disorders such as galactosemia, hypoparathyroidism, pseudohypoparathyroidism, hypophosphatasia, prolonged corticosteroid therapy or rapid corticosteroid withdrawal, possibly growth hormone treatment, refeeding of a significantly malnourished child, hypervitaminosis A, severe vitamin A deficiency, Addison disease, obesity, menarche, oral contraceptives, and pregnancy; infections such as roseola infantum, sinusitis, chronic otitis media and mastoiditis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome; drugs such as nalidixic acid, doxycycline, minocycline, tetracycline, nitrofurantoin, isotretinoin used for acne therapy especially when combined with tetracycline, and sodium valproate; hematologic disorders such as polycythemia, various anemias, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome; and, importantly, obstruction of intracranial drainage by cerebral venous thrombosis.

Table 623.1

Clinical Manifestations

IIH is rare under the age of 10 yr, with a female sex preponderance and for reasons that are poorly understood, patients are much more likely to be obese. The most frequent symptom is chronic (weeks-to-months), progressive, frontal headache that may worsen with postural changes or a Valsalva maneuver. Although vomiting may occur, it is rarely as persistent and insidious as that associated with a posterior fossa tumor. Transient visual obscuration (TVO) lasting seconds and diplopia (secondary to dysfunction of the abducens nerve) may also occur, as may pulsatile tinnitus. TVO is a transient graying out or vision loss often associated with postural changes or Valsalva maneuvers. Children are alert and lack constitutional symptoms. Papilledema with an enlarged blind spot is the most consistent sign. It is frequently misdiagnosed. The optic nerve head drusen and/or optic neuritis may be mistaken for papilledema. Hence, optical coherence tomography (Fig. 623.2 ) and B -ultrasound are strongly advised in all cases. Inferior nasal or peripheral visual field defects may be detected. The presence of other focal neurologic signs should prompt an investigation to uncover a process other than IIH. All children should undergo cranial MRI, which may show papilledema or enlargement of the optic nerve sheaths/pituitary fossa, but nothing else. MR venography is essential, both to exclude a venous thrombosis and to identify the tapering of the lateral sinuses that is commonly seen in intracranial hypertension.

All children will require measurement of their CSF pressure. Standard opening pressures in cm H2 O using a manometer can be falsely raised. More accurate recording will be achieved using an electronic transducer (similar equipment routinely attaches onto an arterial line), which will give a computer-aided recording with waveform analysis, both on opening and in steady state for 20 min (when relaxed, happy, in the lateral decubitus position, and not held tightly or in the overflexed position). Cooperation of the child is required and is helped by the presence of a play specialist or use of nitrous oxide during needle insertion thereby avoiding pain, crying, Valsalva maneuver, or abnormal respiration. When lumbar puncture opening pressure is measured under general anesthesia, it is important to record a normal end-tidal partial pressure of carbon dioxide (ET-pCO2 ). Because secondary IH is more common, renal, liver, thyroid, hematologic, inflammatory, and autoimmune profiles should be obtained on venous blood testing. The tests are likely to help reduce the false-positive rate. CSF infusion studies can also be helpful, particularly in borderline cases. A summary of diagnostic criteria is noted in Table 623.2 .

Table 623.2

The diagnosis of IIH is considered probable if A–D are met but the CSF pressure is below 250 mm.

From Mollan SP, Ali F, Hassan-Smith G, et al: Evolving evidence in adult idiopathic intracranial hypertension: pathophysiology and management, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 87(9):982-992, 2016, Table 1.

Treatment

There are no randomized clinical trials to guide the treatment of IIH. Optic atrophy and visual impairment are the most significant complications. Any causes of secondary IH should be treated (e.g., withdrawal of a drug). Obese children with IIH need a weight-loss regimen. Acetazolamide (10-30 mg/kg/24 hr) probably is an effective regimen, and, more recently, some authors have recommended using topiramate or furosemide. Corticosteroids are not routinely administered, although they may be used in a patient with severe intracranial hypertension who is at risk of losing visual function and awaiting surgical intervention; rarely, a ventriculoperitoneal or lumboperitoneal shunt is necessary.

Optic nerve sheath fenestration may also be attempted in refractory situations of IIH, but its value is debated. Any child whose intracranial pressure proves to be refractory to treatment warrants repeat full investigation. Serial monitoring of visual function (i.e., visual acuity, color vision, and visual fields) is required in children old enough to participate. Serial optic nerve examination is also essential. Optical coherence tomography is useful to serially follow changes in papilledema. Serial visual-evoked potentials are useful if the visual acuity cannot be reliably documented. The initial diagnostic lumbar puncture may be therapeutic. The spinal needle produces a small rent in the dura that allows CSF to escape the subarachnoid space, thus reducing intracranial pressure. Several additional lumbar taps and the removal of sufficient CSF to reduce the opening pressure by 50% occasionally lead to resolution of the process.