Orbital Infections

Scott E. Olitsky, Justin D. Marsh, Mary Anne Jackson

Orbital infections are common in children. It is important to be able to distinguish the different forms of infection that occur in the orbital region, to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment to prevent loss of vision or spread of the infection to the nearby intracranial structures (Table 652.1 ).

Table 652.1

Manifestations of Orbital Cellulitis Associated With Ethmoid Sinusitis

| MANIFESTATIONS | CLINICAL AND CT IMAGING DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory edema | Eyelid edema and erythema; eye may be swollen shut |

| Fever | |

| Painless extraocular muscle movement; full range of motion | |

| Visual acuity normal | |

| Edema of orbit without abscess formation | |

| Orbital cellulitis | Inflammation of orbital contents without discrete abscess formation |

| Fever, malaise | |

| Subperiosteal abscess | Purulent exudate beneath medial orbital periosteum of lamina papyracea |

| Pain on extraocular muscle movement | |

| Fever, malaise | |

| Displacement of globe (down and out) | |

| Orbital abscess/orbital apex syndrome | Purulent collection within orbit |

| Proptosis, chemosis | |

| Ophthalmoplegia; pain on extraocular muscle movement | |

| Decreased vision | |

| Fever, malaise | |

| Septic cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis | Bilateral (contralateral) eye findings; ptosis, proptosis, swelling, ophthalmoplegia |

| Severe headaches | |

| Meningismus, fever, severe malaise | |

| Decreased vision |

Dacryoadenitis

Dacryoadenitis is inflammation of the lacrimal gland; it most commonly occurs in the pediatric population and in some young adults and is related to a variety of infectious pathogens. Pain, redness, swelling, increase in tearing, and discharge over the lacrimal gland are noted and usually visible at the lateral one third of the upper eyelid; concurrent preauricular lymphadenopathy may be noted (Fig. 652.1 ). It may occur with mumps (in which case it is usually acute and bilateral, subsiding in a few days or weeks), with influenza, infectious mononucleosis, and herpes zoster. Staphylococcus aureus may produce a suppurative dacryoadenitis, and other bacterial causes include streptococci and Neisseria gonorrhoeae . Chronic dacryoadenitis is associated with certain systemic diseases, particularly sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and syphilis. Some systemic diseases may produce enlargement of the lacrimal and salivary glands (Mikulicz syndrome).

Dacryocystitis

Dacryocystitis is an infection of the lacrimal sac and generally requires obstruction of the nasolacrimal system to allow its development. Acute, subacute, and chronic forms are described. Most patients with dacryocystitis present with redness and swelling over the region of the lacrimal sac (Fig. 652.2 ). It is treated with warm compresses and systemic antibiotics. This helps control the infection, but the obstruction usually requires definitive treatment to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Dacryocystitis may occur in newborns as a complication of a congenital dacryocystocele (see Chapter 643 ). If present, systemic antibiotics and digital pressure for decompression are recommended. The obstruction of the nasolacrimal system may resolve once the infection clears. If spontaneous resolution does not occur, probing should be considered within a short time frame. An intranasal cyst may be present in conjunction with the dacryocystocele. If this occurs, marsupialization of the cyst may be needed at the time of the probing.

Preseptal Cellulitis

Inflammation of the lids and periorbital tissues without signs of true orbital involvement (such as proptosis or limitation of eye movement) is generally referred to as periorbital or preseptal cellulitis and is a form of facial cellulitis. This is a common entity in young children, usually under age 5 yr, and may be caused by direct seeding related to bacteremia (usually seen in those <3 yr), sinusitis, trauma, or other infected wound in the periorbital region, or an abscess of the lid or periorbital region (pyoderma, hordeolum, conjunctivitis, dacryocystitis, insect bite). Brown recluse spider bites are often associated with considerable local swelling, and in the first 24 hr, the bite itself may not be obvious to the parent or the examiner.

Patients present with eyelid swelling; the edema may be so intense as to make it difficult to evaluate the globe. Prior to the Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccine, the most common cause of pediatric preseptal (facial) cellulitis was bacteremia caused by Hib. Group A streptococcus, pneumococcus, and S. aureus (especially if related to an infected wound or bite) are now the most common etiologic agents. Occasionally young children with herpes simplex virus infection of the periorbital tissues will present first with swelling and redness, followed by the appearance of discrete tiny ulcers.

Clinical examination will show lack of proptosis, normal ocular movement, and normal pupil function. CT imaging can demonstrate edema of the lids and subcutaneous tissues anterior to the orbital septum (Fig. 652.3 ); however, imaging is not necessary in those without signs of an orbital process. Antibiotic therapy and careful clinical monitoring and evaluation to identify signs of local progression are essential. In well-appearing children with infected traumatic wounds or insect bites associated with periorbital cellulitis, oral antibiotics that target S. aureus and GAS may be considered. For young children in whom a hematogenous process is suspected, or in any toxic, ill appearing child, blood cultures should be obtained, and hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics are required. Most recommend intravenous ampicillin with sulbactam or intravenous clindamycin plus cefotaxime (or ceftriaxone) for hospitalized patients.

Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis is a severe, rapidly spreading form of periorbital bacterial infection, involving both superficial and deep fascial planes. The disease may have no preceding events or may follow trauma to the periorbital skin. Initial symptoms resemble periorbital/facial cellulitis but rapidly progress to tissue necrosis, blistering, and significant systemic toxicity. Streptococci and S. aureus are the most common pathogens. Treatment includes broad spectrum antibiotics, surgical debridement, and when available, hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Orbital Cellulitis

Inflammation of the tissues of the orbit, characterized by the triad of proptosis, painful limitation of movement of the eye, and potentially decreased visual acuity, is termed orbital cellulitis (see Table 652.1 ). Edema of the conjunctiva (chemosis) and inflammation and swelling of the eyelids may be seen. The mean age is 6.8 yr, ranges from 1 wk to 16 yr, and a 2 : 1 predilection in boys is reported. An increased risk is seen in the winter, as complicated sinusitis often follows respiratory viral infection (e.g., influenza). Patients often feel ill, are febrile, and appear toxic, and leukocytosis sometimes but not always may be appreciated (also see Chapter 221 ). Practitioners should have an increased clinical suspicion for intracranial extension in those with headache, vomiting, and always if any focal neurologic findings are present.

Orbital cellulitis may follow direct infection of the orbit from a wound, hematogenous seeding of organisms during bacteremia, or more often direct extension or venous spread of infection from contiguous sites such as the lids, conjunctiva, globe, lacrimal gland, nasolacrimal sac, or more commonly from the paranasal (ethmoid) sinuses. The differential diagnosis includes idiopathic orbital inflammation, myositis, sarcoidosis, granulomatous vasculitis, leukemia, lymphoma, histiocytic disorders, rhabdomyosarcoma, ruptured dermoid cyst, orbital trauma, and orbital foreign body. In some cases, primary or metastatic tumor in the orbit can produce the clinical picture of orbital cellulitis.

While the most common cause of orbital cellulitis in children is direct extension or venous spread from infected paranasal sinuses, an antecedent history of sinusitis requiring antibiotic therapy is generally not reported. The spread of infection to the orbit from the sinuses is more prevalent in children because of their thinner bony septa and sinus wall, greater porosity of bones, open suture lines, and larger vascular foramina. The spread of infection is also facilitated by the venous and lymphatic communication between the sinuses and surrounding structures, which allow flow in either direction, facilitating retrograde thrombophlebitis. Frequently noted pathogenic organisms include group A streptococcus, streptococcus species (especially Streptococcus anginosus also known as the Streptococcus milleri group), and anaerobes (e.g., Bacteroides spp., Prevotella spp.). S. aureus , including methicillin-resistant S. aureus , may be seen, most often in older patients. Occasionally group C streptococci are implicated in orbital infections. Streptococcus pneumoniae , group A streptococcus, and less commonly Haemophilus species may be identified in bacteremic cases.

The potential for complications is great. Visual loss can occur secondary to an increase in orbital pressure that causes retinal artery occlusion or optic neuritis. This is more likely to occur in the presence of an orbital abscess. Extension of infection from the orbit into the cranial cavity may lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis or meningitis, epidural or subdural empyema, or brain abscesses. Additional complications include optic atrophy, exposure keratitis, and retinal or choroidal ischemia. Therefore an interdisciplinary team involving an infectious disease specialist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist, and where indicated, a pediatric neurosurgeon should be involved in the care of the patient with orbital infection.

Orbital cellulitis must be recognized promptly and treated aggressively. Hospitalization and systemic antibiotic therapy are indicated. All patients should undergo CT imaging of the orbit, paranasal sinuses, and imaging should be performed with intravenous contrast. Additional brain imaging should be performed to evaluate for intracranial extension. Lumbar puncture should be considered only in those with a meningitis presentation, assuming there are no signs of elevated intracranial pressure or focal neurologic findings on examination. Parenteral antibiotics should be initiated immediately. Antimicrobial agents should begin with intravenous ampicillin with sulbactam OR intravenous clindamycin plus ceftriaxone, cefepime (or cefotaxime when available); in cases where there is suspicion for intracranial extension, vancomycin plus cefotaxime (or ceftriaxone) plus metronidazole should be given.

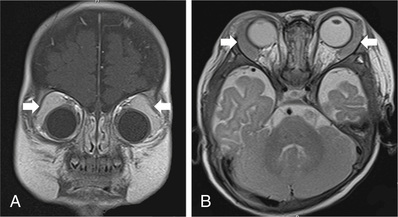

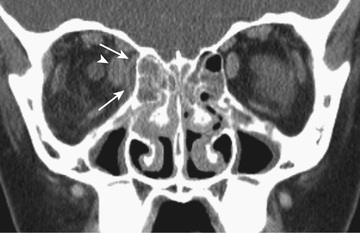

If the patient does not show evidence of improvement or if there are signs of progression, sinus drainage should be considered. The presence of an orbital or subperiosteal abscess (Figs. 652.4 and 652.5 ) may require urgent drainage of the orbit. The clinical presentation and course of each individual patient should dictate the need and timing of abscess drainage.

Children <9 yr of age with a medial subperiosteal abscess can initially be managed with intravenous antibiotics, which usually are sufficient for resolution of the abscess. Patients should be examined frequently (every 6 hr until improvement) for signs of visual deterioration or pupillary abnormalities. Most will become afebrile within 48 hr and have examination improvement by 72 hr. If there are pupillary abnormalities, decreased vision, or failure to improve, the subperiosteal abscess should be drained. Many recommend routine drainage for a subperiosteal abscess in children >9 yr of age. Operative procedures should be coordinated with the otolaryngologist to allow for sinus drainage at the same time that the subperiosteal abscess is drained, and cultures should be obtained from the sinus and the abscess.

If there is an orbital abscess , drainage should be performed of the orbit and cultures should similarly be obtained from sinuses and the orbital abscess. Coordinated procedures with the ophthalmologist and otolaryngologist should be undertaken so that sinus drainage can be provided under the same anesthesia. Similarly, if neurosurgical intervention is required, operative coordination should occur with ophthalmology and otolaryngology; cultures should be obtained. The use of adjunctive corticosteroids, sinus rinses, and anticoagulation for cavernous venous thrombosis and or superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis is controversial.