Congenital Malformations of the Ear

Joseph Haddad Jr, Sonam N. Dodhia

The external and middle ears, derived from the first and second branchial arches and grooves, grow throughout puberty, but the inner ear, which develops from the otocyst, reaches adult size and shape by midfetal development. The ossicles are derived from the first and second arches (malleus and incus), and the stapes arises from the second arch and the otic capsule. The malleus and incus achieve adult size and shape by the 15th wk of gestation, and the stapes achieves adult size and shape by the 18th wk of gestation. Although the pinna, ear canal, and tympanic membrane (TM) continue to grow after birth, congenital abnormalities of these structures develop during the first half of gestation. Malformed external and middle ears may be associated with serious renal anomalies, mandibulofacial dysostosis, hemifacial microsomia, and other craniofacial malformations. Facial nerve abnormalities may be associated with any of the congenital abnormalities of the ear and temporal bone. Malformations of the external and middle ears also may be associated with abnormalities of the inner ear and both conductive hearing loss (CHL) and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL).

Congenital ear problems may be minor and mainly cosmetic, or major, affecting both appearance and function. Any child born with an abnormality of the pinna, external auditory canal, or TM should have a complete audiologic evaluation in the neonatal period. Imaging studies are necessary for evaluation and treatment; in the patient with other craniofacial abnormalities, a team approach with other specialists can assist in guiding therapy.

Pinna Malformations

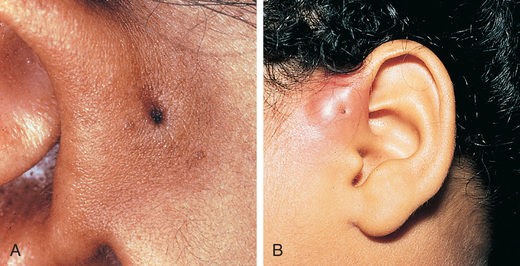

Severe malformations of the external ear are rare, but minor deformities are common. Isolated abnormalities of the external ear occur in approximately 1% of children (Fig. 656.1 ). A pit-like depression just in front of the helix and above the tragus may represent a cyst or an epidermis-lined fistulous tract (Fig. 656.2 ). These are common, with an incidence of approximately 8 in 1,000 children, and may be unilateral or bilateral and familial. The pits require surgical removal only if there is recurrent infection. Accessory skin tags , with an incidence of 1-2/1,000 live births, can be removed for cosmetic reasons by simple ligation if they are attached by a narrow pedicle (see Fig. 656.1 ). If the pedicle is broad based or contains cartilage, the defect should be corrected surgically. An unusually prominent or “lop” ear results from lack of bending of the cartilage that creates the antihelix. It may be improved cosmetically in the neonatal period by applying a firm framework (sometimes soldering wire is used) attached by Steri-Strips to the pinna and worn continuously for weeks to months. Otoplasty for cosmetic correction can be considered in children older than 5 yr of age, when the pinna has reached approximately 80% of its adult size.

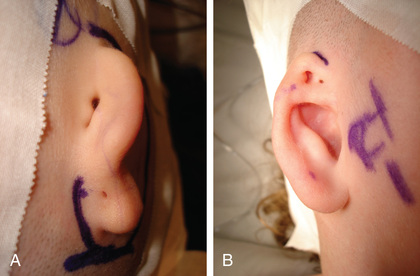

The term microtia may indicate subtle abnormalities of the size, shape, and location of the pinna and ear canal, or major abnormalities with only small nubbins of skin and cartilage and the absence of the ear canal opening; anotia indicates complete absence of the pinna and ear canal (Fig. 656.3 ). Microtia can have a genetic or environmental predisposition. Several hereditary forms of microtia have been identified that exhibit either autosomal dominant or recessive mendelian inheritance. In addition, some forms due to chromosomal aberrations have been reported. Most of the responsible genes that have been identified are homeobox genes, which are involved in the development of pharyngeal arches. Microtic ears often are more anterior and inferior in placement than normal auricles, and the location and function of the facial nerve may be abnormal. Surgery to correct microtia is considered for both cosmetic and functional reasons; children who have some pinna can wear regular glasses, a hearing aid, and earrings, and feel more normal in appearance. If the microtia is severe, some patients may opt for creation and attachment of a prosthetic ear, which cosmetically closely resembles a real ear. Surgery to correct severe microtia may involve a multistage procedure, including carving and transplantation of autogenous cartilage rib grafts and local soft tissue flaps. Cosmetic reconstruction of the auricle usually is performed between 5 and 7 yr of age and is performed before canal atresia repair in children deemed appropriate for this surgery.

Congenital Stenosis or Atresia of the External Auditory Canal

Stenosis or atresia of the ear canal often occurs in association with malformation of the auricle and middle ear. Malformations can occur in isolation or as part of a genetic syndrome. For example, the ear canal is narrow in trisomy 21, and external canal stenosis or atresia is common in branchiooculofacial syndrome, leading to CHL. Audiometric evaluation of these children should be undertaken as early in life as possible. Most children with significant CHL secondary to bilateral atresia wear bone conduction hearing aids for the 1st several years of life. Diagnosis, evaluation, and surgical planning often are aided by CT, and sometimes MRI, of the temporal bone. Mild cases of ear canal stenosis do not require surgical enlargement unless the patient develops chronic external otitis or severe cerumen impaction that affects hearing.

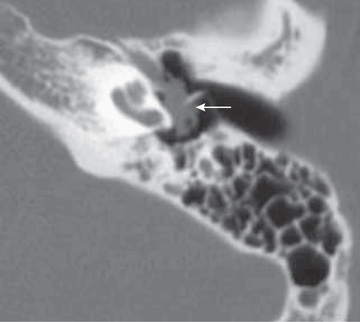

Reconstructive ear canal and middle-ear surgery for atresia usually is considered for children older than 5 yr of age who have bilateral deformities resulting in a significant CHL. The aim of reconstructive surgery is to improve hearing to a point where the child may not need a hearing aid or to provide an ear canal and pinna so that the child can derive improved benefit from an air-conduction hearing aid. Hearing results for atresiaplasty range from fair to excellent. CT evidence of an adequate middle-ear cleft, ossicles, and mastoid is required to perform the surgery; the position of the facial nerve, which often is in an abnormal location in these children, also must be considered (Fig. 656.4 ). The use of bone-anchored hearing aids is a safe, reliable, and low-risk alternative to atresiaplasty and hearing results are generally excellent. Bone-anchored hearing aids may also be useful for rehabilitation of nonoptimal atresiaplasty hearing results. These devices are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for surgical placement in children age 5 yr and older; prior to age 5 yr, they can be worn with a soft band around the head. Disadvantages include the fact that cosmesis is not very good (a bone-anchored hearing aid has a visible titanium abutment and snap-on hearing aid) and frequent wound care is required. Middle ear implants are effective alternatives for those who cannot tolerate foreign bodies in the ear for medical reasons or rely on good perception of high-frequency sounds.

Congenital Middle-Ear Malformations

Children may have congenital abnormalities of the middle ear as an isolated defect or in association with other abnormalities of the temporal bone, especially the ear canal and pinna, or as part of a syndrome. Affected children usually have CHL but may have mixed CHL and SNHL. Most malformations involve the ossicles, with the incus most commonly affected. Other less-common abnormalities of the middle ear include persistent stapedial artery, high-riding jugular bulb, and abnormalities of the shape and volume of the aerated portion of the middle ear and mastoid; all present problems for a surgeon. Depending on the type of abnormality and the presence of other anomalies, surgery may be considered to improve hearing.

Congenital Inner Ear Malformations

Congenital inner ear malformations have been identified and classified as a result of improvements in imaging modalities, especially CT and MRI. As many as 20% of children with SNHL may have anatomic abnormalities identified on CT or MRI. Congenital malformations of the inner ear usually are associated with SNHL of various degrees, from mild to profound. These malformations are most commonly found in infants and may occur as isolated anomalies or in association with other syndromes, genetic abnormalities, or structural abnormalities of the head and neck. High-resolution temporal bone CT can identify enlarged vestibular aqueducts and cochlear nerve canal stenosis in association with SNHL. Although no therapy exists for this condition, it may be associated with progressive SNHL in some children; therefore diagnosis may have some prognostic value.

Congenital perilymphatic fistula of the oval or round window membrane may present as a rapid-onset, fluctuating, or progressive SNHL with or without vertigo, and often is associated with congenital inner ear abnormalities. Middle-ear exploration may be required to confirm this diagnosis, because no reliable nonoperative diagnostic test exists. It may be necessary to repair a perilymphatic fistula to prevent possible spread of infection from the middle ear to the labyrinth or meninges, to stabilize hearing loss, and to improve vertigo when present.

Congenital Cholesteatoma

A congenital cholesteatoma (approximately 2–5% of all cholesteatomas) is a nonneoplastic, destructive, cystic lesion that usually appears as a white, round, cyst-like structure medial to an intact TM. Cysts are seen most commonly in boys and in the anterior-superior portion of the middle ear, although they can present in other locations and within the TM or in the skin of the ear canal. They can be classified as “open,” meaning in direct continuity with mucosa of the middle ear, or “closed.” Affected children often have no prior history of otitis media. One theory for the pathogenesis is that the cyst derives from a congenital rest of epithelial tissue that persists beyond 33 wk of gestation, when it ordinarily would disappear. Other theories include squamous metaplasia of the middle ear, entrance of squamous epithelium through a nonintact eardrum into the middle ear, ectodermal implants between the first and second branchial arch remnants, and residual amniotic fluid squamous debris. Congenital or acquired cholesteatoma should be suspected when deep retraction pockets, keratin debris, chronic drainage, aural granulation tissue, or a mass behind or involving the TM is present. Congenital cholesteatoma is often asymptomatic whereas acquired cholesteatoma commonly presents with otorrhea. Besides acting as a benign tumor causing local bone destruction, the keratinaceous debris of a cholesteatoma serves as a culture medium, leading to chronic otitis media. Complications include ossicular erosion with hearing loss, bone erosion into the inner ear with dizziness, or exposure of the dura, with consequent meningitis or a brain abscess. Evaluation includes a CT scan (Fig. 656.5 ) to detect bone erosion, and audiometry to assess air and bone conduction and speech reception and discrimination. Treatment includes cholesteatoma removal, repair of damaged small middle ear bones, and mastoidectomy in 50% of congenital and >90% of acquired cholesteatoma cases. A second-look procedure 6-9 mo after primary surgery is usually recommended to detect and remove small amounts of residual disease prior to more extensive recurrence or development of complications. Higher initial stage of disease, erosion of ossicles, cholesteatoma abutting or enveloping the incus or stapes, and need for removal of the ossicles are associated with increased likelihood of residual cholesteatoma, which occurs in ~10% of congenital and ~25% of acquired cases. More extensive disease at initial surgery is associated with poorer hearing outcomes. Children with significant inflammation or extensive scarring may require a 2-stage procedure with initial removal of the cholesteatoma and subsequent repair of damaged middle ear structures.