Acute Mastoiditis

John J. Faria, Robert H. Chun, Joseph E. Kerschner

Mastoiditis, a suppurative infection of the mastoid air cell system, is one of the most common infectious complications of acute otitis media. Coalescent mastoiditis occurs when the suppurative infection leads to bony breakdown of the fine bony septa separating individual mastoid air cells.

Anatomy

The temporal bone forms a portion of the skull base and has multiple complex anatomic functions. The mastoid process is a pyramid-shaped outgrowth of the temporal bone. The inferior extent is attached to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The mastoid process borders the middle cranial fossa, posterior cranial fossa, and sigmoid sinus. It is composed of a system of interlinked mucosa-lined air cells that communicate with the middle ear space and contains the fallopian canal, which includes the facial nerve, the chorda tympani supplying taste to the anterior two third of the tongue, and the semicircular canal system. Because the mastoid cavity is anatomically adjacent to the meninges, brain, venous sinuses of the brain, facial nerve, and cervical lymph nodes, mastoiditis often accompanies or precedes intracranial complications of acute otitis media.

Epidemiology

In the preantibiotic era, acute mastoiditis was much more common than nowadays and a feared complication of acute otitis media (AOM) with high rates of intracranial infectious complications, morbidity, and mortality. Mastoiditis currently occurs in approximately 1-4 cases per 100,000 population <2 yr and less commonly among older children. A multicenter study with 223 consecutive cases of acute mastoiditis reported 28% of patients were younger than 1 yr of age, 38% of patients were between 1 and 4 yr of age, 22% of patients were between 4 and 8 yr of age, and 8% of patients were between 8 and 18 yr of age. Some studies reported decreased incidence of acute mastoiditis following introduction of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) while others reported no change or nominal increases. One study reported a sharp decrease in acute mastoiditis beginning in 2010, which coincided with licensure and widespread use of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). Another study, which included data from 8 hospitals, found that the proportion of PCV13 serotypes isolated from cases of mastoiditis decreased from 50% in 2011 to 29% in 2013, with most of the decrease attributable to decreases in serotype 19A. Changes in rates of mastoiditis are likely related to changing incidence of acute otitis media in response to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Other factors influencing the occurrence of mastoiditis include rate of antibiotic prescription for AOM, access to healthcare, and rates of antimicrobial resistance. In countries such as the Netherlands and Iceland that adhere to a watchful waiting strategy for treatment of AOM, rates of acute mastoiditis have increased slightly compared with countries where antibiotics are routinely used to treat AOM, although the causal nature of this relationship is unclear. Despite large differences in antibiotic prescription rates in different countries, due to the overall low incidence of acute mastoiditis, the number of children needed to be treated with antibiotics to prevent one case of acute mastoiditis ranges from 2,500 to 4,800. Some studies have reported a recent increase in incidence, which has correlated with an increase in infections with drug resistant bacteria. All-cause mortality among children with mastoiditis is 0.03%.

Microbiology

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the most common pathogen cultured from cases of acute mastoiditis (Table 659.1 ). Following introduction of PCV7, pneumococcal serotype 19A was commonly associated with acute mastoiditis. This serotype is frequently resistant to penicillin and macrolide antibiotics. PCV13 use has been associated with fewer serotype 19A infections overall; its impact on the etiology of mastoiditis is less clear. Other bacteria commonly cultured include Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae . P. aeruginosa is more likely in patients with chronic otitis media and/or cholesteatoma, older children, and those with previous tympanostomy tubes.

Clinical Manifestations

Acute mastoiditis and AOM present similarly in children. Ninety-seven percent of children with an acute mastoiditis have a coexisting acute otitis media on the affected side. The remaining 3% of children with acute mastoiditis either had a serous middle ear effusion at the time of presentation or had a history of AOM within the past 2 wk. Other clinical manifestations include protrusion of the ear (87%), retroauricular swelling and tenderness (67%), retroauricular erythema (87%), fever (60%), otalgia, and hearing loss (Table 659.2 ). Children with acute mastoiditis were less likely to have bilateral infection. Some children do not have external signs of infection.

Table 659.2

Differential Diagnosis of Postauricular Involvement of Acute Mastoiditis With Periosteitis/Abscess

| Disease | POSTAURICULAR SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | External Canal Infection | Middle-Ear Effusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crease* | Erythema | Mass | Tenderness | |||

| Acute mastoiditis with periosteitis | May be absent | Yes | No | Usually | No | Usually |

| Acute mastoiditis with subperiosteal abscess | Absent | Maybe | Yes | Yes | No | Usually |

| Periosteitis of pinna with postauricular extension | Intact | Yes | No | Usually | No | No |

| External otitis with postauricular extension | Intact | Yes | No | Usually | Yes | No |

| Postauricular lymphadenitis | Intact | No | Yes † | Maybe | No | No |

* Postauricular crease (fold) between pinna and postauricular area.

† Circumscribed.

From Bluestone CD, Klein JO, editors: Otitis media in infants and children , ed 3, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 333.

Imaging

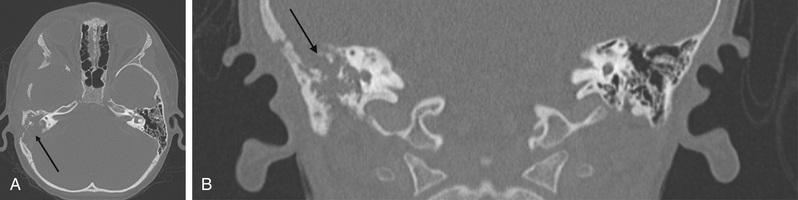

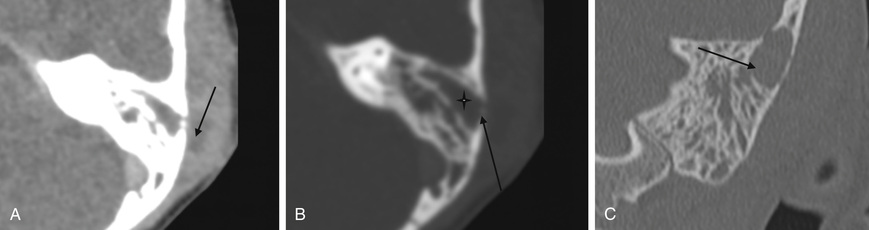

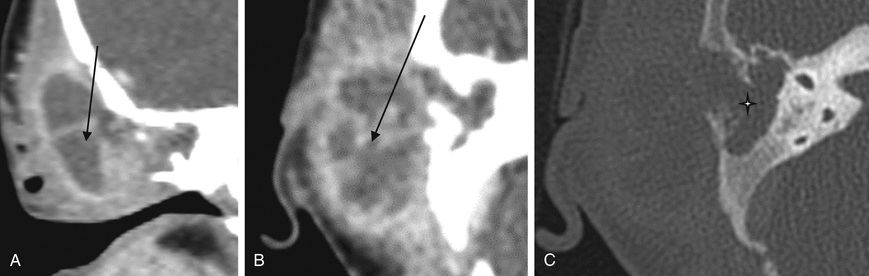

Acute mastoiditis is usually diagnosed based on history and clinical findings. CT scan of the temporal bone can confirm the diagnosis, whereas head CT can identify intracranial complications (see Chapter 658 ), including epidural abscess or subdural empyema. Findings of acute mastoiditis include bony demineralization, loss of bony septations in the mastoid cavity (Fig. 659.1 ), and, occasionally, subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 659.2 ). CT scans have the advantage of being readily available in most emergency rooms, can quickly evaluate for intracranial complications, and can identify whether there is bony destruction or a drainable fluid collection. Contrast administration is necessary as part of the CT scan to allow evaluation for sigmoid sinus thrombosis (Fig. 659.3 ) and to evaluate for abscess formation. Magnetic resonance imaging is generally reserved for patients in whom there is a suspected intracranial complication. Incidental detection of mastoid air cell opacification occurs in more than 20% of children (and in 40% of children younger than 2 yr) undergoing MRI for other reasons, so imaging findings must be interpreted in the appropriate clinical context.

There is a limited role for ultrasound in diagnosis of acute mastoiditis. Ultrasound can be used as a screening test when a postauricular subperiosteal abscess is suspected due to clinical findings such as protrusion of the pinna and retroauricular erythema. If there is a fluid collection on ultrasound or concern for a defect in the cranial vault, further imaging with a CT and/or MRI would be recommended. Because ultrasound cannot identify intracranial complications, its use must be limited to a highly selected patient population.

Management

Managing acute mastoiditis first requires diagnosing it, and in many ways that is the most difficult part of the process. Acute mastoiditis is a rare complication of AOM, and there is a large degree of overlap between the presentations of children with both disease processes. For the pediatrician confronted with a majority of uncomplicated acute otitis media, it is difficult to decide when to initiate a more extensive evaluation. Any time there is a purulent middle ear effusion along with postauricular findings, acute mastoiditis needs to be in the differential diagnosis. In general, children with acute mastoiditis will appear sicker than children with uncomplicated acute otitis media and many of them have already failed to respond to appropriate antibiotic therapy for acute otitis media. Focal neurologic deficits in a child with acute otitis media or mastoiditis suggest intracranial spread of infection or facial paresis as an additional complication. In a child with suspected mastoiditis, it is critical to document normal facial nerve function at the time of the initial exam so that if this complication does develop during the hospital course, the surgical team can be sure of the time course of the complication.

Complete blood count typically reveals leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance. C-reactive protein is often highly elevated. If otorrhea is present, implying a perforated tympanic membrane, the fluid should be sent for gram stain and culture. Blood culture should be considered in any child appearing toxic. For children with postauricular findings consistent with acute mastoiditis, admission to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy and serial exams is recommended.

Deciding whether to obtain imaging is a decision made on an individual patient basis. In highly selected cases, ultrasound can be helpful to differentiate postauricular erythema from a postauricular abscess and avoids the risk of ionizing radiation exposure. However, ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT scanning and will underdiagnose postauricular abscess formation and will provide no information as to whether there is an intracranial complication present such as a brain abscess. Some authors advocate deferring CT scanning in patients with clinically suspected acute mastoiditis and without focal neurologic findings to allow for an initial 24-48 hr period of intravenous antibiotic therapy as an inpatient. If there is any concern about the possibility of an intracranial complication, a contrasted CT scan is the most sensitive test readily available and should be ordered upon presentation.

Antibiotic therapy should initially be administered intravenously. Empiric antibiotic selection may include a β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combination (e.g., ampicillin-sulbactam) or third-generation cephalosporin (e.g., cefotaxime, ceftriaxone). In children with chronically draining ears or concern for cholesteatoma, there is an increased incidence of gram-negative infection and coverage should include antibiotics with activity against Pseudomonas spp. (e.g., ceftazidime, cefepime). If intracranial infection is suspected, broader spectrum antimicrobial coverage (e.g., vancomycin plus a 3rd-generation cephalosporin) should be initiated. In cases of uncomplicated acute mastoiditis (e.g., absence of intracranial complications or localized abscess formation), a 24-48 hr trial of intravenous antibiotics may yield clinical improvement without surgical intervention. The total duration of therapy is 3-4 wk, with transition from intravenous to oral therapy at discharge for those without intracranial complications. The optimal duration of intravenous therapy is unknown, but some experts recommend a minimum of 7 days of intravenous therapy prior to oral transition, whereas others transition once the patient demonstrates clinical improvement and surgical intervention is no longer required.

Otolaryngology consultation can be helpful to assist with management and to determine whether surgical intervention would be beneficial. Many patients will benefit from tympanostomy tube placement at the time of the acute infection to allow localized ototopical antibiotic treatment and aspiration of middle ear fluid for culture and sensitivity. In a patient with an additional extracranial complication such as facial paresis, drainage of the middle ear space with placement of a tympanostomy tube is required and should take place urgently. A small group of patients may necessitate mastoidectomy, surgical removal of diseased bone and granulation tissue in the mastoid cavity. At the time of surgery, a drain is often placed to allow purulent secretions an egress. Indications for mastoidectomy include coalescent mastoiditis, postauricular abscess formation, infectious intracranial complication, and failure to respond to appropriate IV antibiotics. When intracranial complications occur or there are mental status changes, evaluation by otolaryngology and neurosurgery and emergent mastoidectomy are indicated. Most children with mastoiditis make a full recovery. Long-term otologic complications like sensorineural or conductive hearing loss are uncommon. A posttreatment audiogram is often obtained to evaluate the hearing status after an infection.

Special Situations

When treating acute mastoiditis, several uncommon situations require particular attention. Selecting empiric antibiotics for unvaccinated and undervaccinated children is challenging and in this patient population, it is especially important to obtain a sample of middle ear fluid for Gram stain and culture to guide antibiotic therapy. There is an increased incidence in acute mastoiditis in children with autism spectrum disorder. Immunocompromised patients should be treated more aggressive medically with prolonged courses of antibiotic and may benefit from more aggressive surgical treatment to remove infected tissue. Sigmoid sinus thrombosis can occur secondary to acute mastoiditis. If this does occur, in addition to the standard treatment for acute mastoiditis, consideration should be given to involving hematology and for administering systemic anticoagulation. Otitic hydrocephalus, which is elevated intracranial pressure following middle ear infection, is associated with sigmoid sinus thrombosis, and management requires consultation with neurology and/or neurosurgery.

More children with profound sensorineural hearing loss are undergoing cochlear implantation in one or both ears at an early age. One study reported a 3.5% rate of acute mastoiditis in children with a cochlear implant. Despite having a foreign body present in the middle ear and inner ear space, the majority of cases of acute mastoiditis can be managed with tympanostomy tube placement, intravenous antibiotic therapy, and incision and drainage of an abscess without explantation of the device.

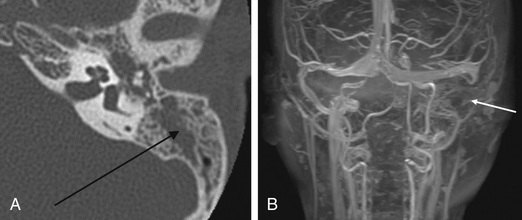

Benign and malignant tumors can affect the temporal bone of children, although these tumors are very rare. The presentation mimics that of chronic otitis media and chronic mastoiditis and this often leads to a delay in diagnosis. Hearing loss, otalgia, and otorrhea are common symptoms. The main differentiating factor is the protracted course of otorrhea and refractory nature of symptoms despite appropriate medical therapy. Aural polyps or a mass lesion may be present on physical exam. Potential causes include rhabdomyosarcoma, nonrhabdomyosarcomatous sarcoma (including chondrosarcoma, chordoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and chloroma), Langerhans cell histiocytosis (formerly histiocytosis X) (Fig. 659.4 ), lymphoma, and metastasis, as well as multiple other rare tumors.