Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Donald Basel

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a heterogeneous group of heritable connective tissue disorders that are grouped into seven pathoetiological categories and more broadly divided into multiple subtypes (Table 679.1 ). Affected individuals are considered to have an overlapping phenotype of abnormally soft, extensible skin, which often heals poorly, in association with joint hypermobility and occasional instability believed to be rooted in a disruption of normal collagen function (Tables 679.2 and 679.3 ). The variable expression, modes of inheritance and unique phenotypic elements distinguish the subtypes from one another. The hypermobility type is the most common form and is the subject of significant clinical and research interest, given its myriad medical associations and the high population frequency of hypermobility—an estimated 3% of the general population.

Table 679.1

Classification of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

| TYPE | GENE | SKIN FINDINGS | JOINT CHANGES | INHERITANCE | OTHER COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic | COL5A1, COL5A2 (usually haploinsufficiency) | Hyperextensibility, bruising, velvety skin, widened atrophic scars, molluscoid pseudotumors, spheroids | Hypermobility and its complications, joint dislocations | AD | Mitral valve prolapse, hernias |

|

COL1A1 Specific pathogenic variant; c.934C>T |

AD | Blue sclerae, short stature, osteopenia/fractures; may have late arterial rupture | |||

| CLASSIC VARIANTS | |||||

| Cardiac valvular | Biallelic loss of function for COL1A2 | Classic EDS features | AR | Severe cardiac valve issues as adult | |

| Periodontal |

C1R C1S |

Can have classic EDS features | Can have hypermobility | AD | Periodontitis, marfanoid habitus, prominent eyes, short philtrum |

| Classic-like | TNXB | Hyperextensibility, marked hypermobility, severe bruising, velvety skin, no scarring tendency | Hypermobility | AR | Parents (especially mothers) with one TNXB mutation; can have joint hypermobility |

| Hypermobility | Unknown | Mild hyperextensibility, scarring, textural change | Hypermobility, chronic joint pain, recurrent dislocations | AD | Sometimes confused with joint hypermobility syndrome |

| Vascular |

COL3A1 Rare variants in COL1A1 |

Thin, translucent skin, bruising, early varicosities, acrogeria | Small joint hypermobility | AD | Abnormal type III collagen secretion; rupture of bowel, uterus, arteries; typical facies; pneumothorax |

| Kyphoscoliosis |

PLOD (deficient lysyl hydroxylase) FKBP14 |

Soft, hyperextensible skin, bruising, atrophic scars | Hypermobility | AR | Severe congenital muscle hypotonia that improves a little in childhood; congenital kyphoscoliosis, scleral fragility and rupture, marfanoid habitus, osteopenia, sensorineural hearing loss |

| VARIANTS WITH KYPHOSCOLIOSIS | |||||

| Spondylocheirodysplastic form |

SLC39A13, which encodes the ZIP13 zinc transporter β4GALT7 or β3GalT6, encoding galactosyltransferase I or II, key enzymes in GAG synthesis |

Similar to kyphoscoliotic form | AR | Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia; can have bone fragility and severe progressive kyphoscoliosis without congenital hypotonia; moderate short stature, loose facial skin, wrinkled palms with thenar and hypothenar atrophy, blue sclerae, curly hair, alopecia | |

| Brittle cornea syndrome | ZNF469 or PRDM5 | Skin hyperextensibility | Joint hypermobility | AR | Kyphoscoliosis; characteristic thin, brittle cornea, ocular fragility, blue sclera, keratoconus |

| Musculocontractural |

CHST14 (encoding dermatan 4-O-sulfotransferase) DSE (encoding dermatan sulfate epimerase) |

Fragile, hyperextensible skin with atrophic scars and delayed wound healing | Hypermobility | AR | Progressive kyphoscoliosis; adducted thumbs in infancy, clubfoot, arachnodactyly, contractures, characteristic facial features, hemorrhagic diathesis |

| Myopathic | COL12A1 | Soft, hyperextensible | Hypermobile small joints, large joint contractures (hip, knees, elbows) | AD or AR | Characterized by muscle hypotonia and weakness |

| Arthrochalasis | Exon 6 deletion of COL1A1 or COL1A2 | Hyperextensible, soft skin with or without abnormal scarring | Marked hypermobility with recurrent subluxations | AD | Congenital hip dislocation, arthrochalasis, multiplex congenita, short stature |

| Dermatosparaxis | Type I collagen N-peptidase ADAMTS-2 | Severe fragility, sagging, redundant skin | AR | Also occurs in cattle | |

AD, Autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; EDS, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome; GAG, glycosaminoglycan.

From Malfait F, Francomano, Byers P, et al: The 2017 International Classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 175(1):8-26, 2017.

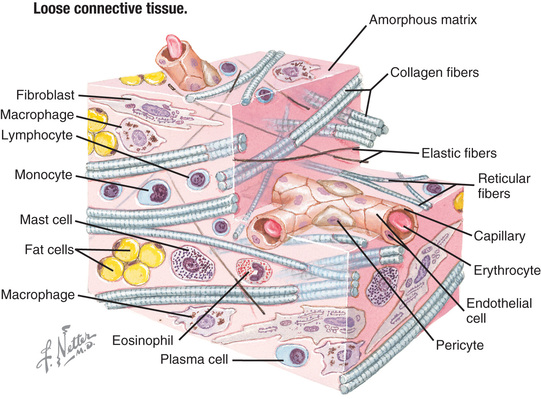

The connective tissue matrix is complex (Fig. 679.1 ) and the interplay of cells, collagen and elastin fibers, proteins, and cell signaling molecules remains poorly understood. However, dysfunction at a structural and functional level more than likely explain the complex medical associations typically encountered in this population, with complaints ranging from joint instability and tissue fragility to chronic pain, autonomic dysfunction, and chronic fatigue (see Table 679.3 ).

Classification of the 6 Most Common Subtypes of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Classic (Genes: COL5a1 , COL5a2 , COL1a1 ; Previously EDS Type I—Gravis, EDS Type II—Mitis)

Classic EDS is the 2nd most common form of EDS and is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder characterized by skin hyperelasticity (Fig. 679.2 ), widened atrophic scars (skin fragility) and joint hypermobility. Other features include easy bruising, which is often associated with hemosiderin staining of the tissues (particularly over regions exposed to frequent trauma, like the shins). The skin is “velvet” to the touch and is particularly fragile, with minor lacerations forming gaping wounds that leave broad, atrophic, papyraceous (“cigarette paper”) scars (see Table 679.2 and Fig. 679.3 ). Additional cutaneous manifestations include molluscoid pseudotumors over pressure points from accumulations of connective tissue and piezogenic papules (Fig. 679.4 ). Joints are hypermobile, often with joint instability (Fig. 679.5 ). Scoliosis frequently presents in adolescence and mitral valve prolapse is common. Life expectancy is generally not reduced, although rare rupture of large arteries has been reported. Similar noncutaneous nonarticular comorbidities as seen in hypermobile EDS are found, in particular pain and gastrointestinal dysfunction (see Table 679.3 ). Premature birth caused by rupture of membranes of an affected offspring is not uncommon. The diagnosis is made by clinical findings and sequencing of COL5a1 and COL5a2 genes.

Hypermobile (Cause Unknown, Previously EDS Type III)

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS) is the most prevalent form of EDS with an estimated population frequency of between 0.75% and 2%. It is an autosomal dominant disorder, but the causative molecular pathoetiology remains elusive in the majority of affected individuals. Fewer than 3% of patients with a hEDS phenotype are associated with heterozygous tenascin X gene loss of function, whereas a minority of cases are linked to other findings, such as the association with mosaic type 1 collagen defects. Tenascin X was originally identified to cause a recessive form of EDS with characteristics similar to those of classic EDS.

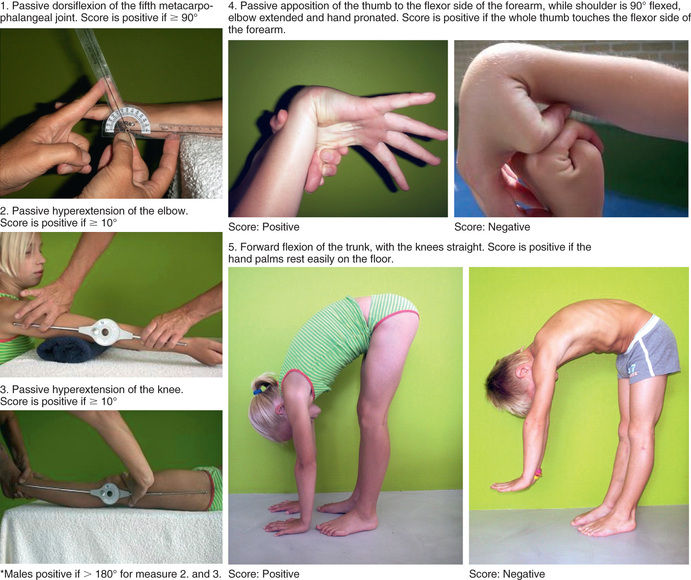

The primary clinical finding in hEDS is generalized joint hypermobility with less prominent skin manifestations. There is inconsistency in the literature as to what defines hypermobility, but generally a score of ≥6 on the Beighton hypermobility scale (Fig. 679.6 , Table 679.4 ) would qualify as hypermobility in an individual between the ages of 6 and 35 years. Children <6 years of age generally tend toward a hypermobile state. However, joints begin to stiffen in the 4th decade, at which time a score of 3+ is considered significant in the context of a history of joint hypermobility (Table 679.5 ). Joint instability with frequent dislocations is common but not universal; joints are predisposed to osteoarthritis in adults.

Table 679.4

One point may be gained for each side for maneuvers 1-4, so the hypermobility score will have a maximum of 9 points if all are positive.

From Hakim A, Grahame R: Joint hypermobility. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 17:989–1004, 2003, Table 1.

Patients with hEDS have significant nonarticular comorbidities associated with functional disorders; these present as complex pain, dysautonomia, chronic fatigue, anxiety, and sleep dysfunction (see Table 679.3 ). The complexity of hEDS most likely originates from the fact that it is genetically heterogeneous and represents an overlapping spectrum of disorders. Although joint hypermobility is the common denominator, symptoms may range from isolated familial joint hypermobility to the extreme multisystem disorder, which significantly impacts daily quality of life. Life expectancy is not reduced. Mild aortic root dilatation has been reported in up to 20% of affected adults. However, this mild dilatation is nonprogressive and not associated with aortic root dissection.

Vascular (vEDS) (Gene: COL3a1 ; Previously EDS Type IV)

vEDS is an autosomal dominant disorder that shows the most pronounced dermal thinning of all types of EDS. Consequently the skin is translucent and the underlying venous network is prominent, most notably over the chest region. The skin has minimal hyperextensibility but has a “velvet” texture and is often described as “doughy.” The joints show increased mobility, often with instability. Congenital club foot and hip dislocation are frequently associated. Tissue fragility and arterial rupture cause significant morbidity and mortality. The majority of affected individuals experience a major vascular event before 20 years of age. Premature birth, extensive ecchymoses from trauma, a high incidence of bowel rupture (especially the colon), uterine rupture during pregnancy (~5% risk), rupture of the great vessels (80% by 40 years of age), dissecting aortic aneurysm, and stroke all contribute to the increased morbidity and shortened life span associated with this condition. The median age of death is estimated at 50 years. Patients are generally counseled regarding the risks associated with pregnancy and advised to avoid activities that raise intracranial or intrathoracic pressure as a result of a Valsalva maneuver (such as weight training or trumpet playing). Skin protection in childhood is important to minimize trauma (shin guards). Celiprolol, a β1 antagonist and a β2 agonist (vasodilator), may reduce vascular events but is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States. The diagnosis is clinical and confirmed by gene sequencing of COL3a1.

Kyphoscoliosis (Gene: PLOD [Lysyl Hydroxylase Deficiency]; Previously EDS Type VI)

The kyphoscoliotic form of EDS is distinguished by the severe kyphoscoliosis that develops early in childhood. It is an autosomal recessive disorder with phenotypic overlap with the classical type of EDS in that the skin is soft and fragile, joints are hyperextensible, and easy bruising is notable from a young age. Unique characteristics include marked hypotonia and keratoconus with corneal fragility; globe rupture has been reported. In addition, there is a higher risk for rupture of medium-sized arteries. The severity of the kyphoscoliosis may lead to restrictive lung disease with secondary pulmonary hypertension and reduced life expectancy. The diagnosis is clinical and confirmed by urine screening for an increased ratio of deoxypyridinoline to pyridinoline cross linking as well as gene sequencing of PLOD.

Arthrochalasia (Gene: COL1a1 , COL1a2 ; Previously EDS Types VIIA and B)

This type of EDS is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder and characterized by severe joint instability in infancy. Joints show marked hyperextensibility with painless dislocation; the skin bruises easily and is soft and hyperextensible. Congenital hypotonia with gross motor delay is common, and kyphoscoliosis can develop in childhood. The diagnosis is clinical and confirmed by gene sequencing of COL1a1 and COL1a2.

Dermatosparaxis (Type 1 Collagen N-Peptidase; Previously EDS Type VIIC)

This type of EDS is a rare autosomal recessive condition characterized by redundant skin that is soft, fragile, and bruises easily. Affected children often have a characteristic facial appearance, with skin sagging into jowls and fullness around the eyes (“puffy”). Premature rupture of membranes is common; closure of fontanels is delayed. Additional unique features reported in this group include short limbs with brachydactyly (short fingers), frequent hernias (umbilical, inguinal), blue sclerae, and bladder rupture. Joints are hypermobile. The diagnosis is confirmed by gene sequencing of ADAMTS2.

Differential Diagnosis

EDS represents a portion of the hereditary connective tissue disorders, many of which have unique features that enable clinical differentiation. The primary differential diagnosis would include Loeys-Dietz syndrome, which has features of both vEDS and Marfan syndrome. EDS has also been confused with MASS syndrome (mitral valve prolapse, aortic root dilation, skeletal changes, skin changes), cutis laxa, and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. In general the skin of patients with cutis laxa hangs in redundant folds, whereas the skin of those with EDS is hyperextensible and snaps back into place when stretched. Other disorders that impact the integrity of the connective tissues—such as exposure to corticosteroids and osteogenesis imperfecta or mild myopathic disorders (Bethlem myopathy, Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy)—can be indistinguishable in the early stages of disease.

General Approach to Management

In addition to the EDS type-specific therapies discussed under each disease, there are general approaches to help improve symptoms and avoid complications.

Musculoskeletal pain, which initially involves the joints, eventually may become generalized and requires a combination of physical therapy and nonpharmacologic approaches. Physical therapy should focus on enhancing the strength of the muscles supporting the affected joints. With severe recurrent sprains or dislocations, bracing may be necessary. Pain medication for low- to moderate-intensity pain could include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (however, their platelet-inhibiting action may increase the risk of cutaneous bleeding). Higher-intensity pain may require other agents, such as selective serotonin receptor inhibitors or low-dose tricyclic antidepressants. Muscle relaxants or antiepileptic agents should be avoided because they may increase fatigue. Surgery for joint dislocations should be avoided if possible, as should prolonged periods of inactivity (which result in rapid muscle deconditioning) (Table 679.6 ). If surgery is needed for any complication, the sutures should approximate the margins, suture tension should be avoided, and the sutures should be retained longer than usual. Other approaches to pain include cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture, and transepidermal electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Chronic fatigue should be approached by supporting good sleep hygiene and avoiding sedating medications (see Table 679.6 ). Patients at risk for arterial bowel or uterine rupture should be counseled about preventive measures, appropriate medications (see specific subtype), and early warning signs of organ rupture.