Arthropod Bites and Infestations

Arthropod Bites

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Arthropod bites are a common affliction of children and occasionally pose a problem in diagnosis. A patient may be unaware of the source of the lesions or may deny being bitten, making interpretation of the eruption difficult. In these cases, knowledge of the habits, life cycle, and clinical signs of the more common arthropod pests of humans may help lead to a correct diagnosis (Table 688.1 ).

Table 688.1

Bed Bugs Versus Other Arthropod Bites: Main Clinical and Epidemiologic Features*

| ARTHROPOD | CLINICAL FEATURES ON EXAMINATION | LOCATION | TIMING OF PRURITUS | CONTEXT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bed bugs | 3-4 Bites in a line or curve | Uncovered areas | Morning | Traveling |

| Fleas | 3-4 Bites in a line or curve | Legs and buttocks | Daytime | Pet owners or rural living |

| Mosquitoes | Nonspecific urticarial papules | Potentially anywhere | Anopheles spp. night; Culex spp. night; Aedes spp. day | Worldwide distribution |

| Head lice | Live lice on the head associated with itchy, scratched lesions | Scalp, ears, and neck | Any | Children, parents, or contact with children |

| Body lice | Excoriated papules and hyperpigmentation; live lice inside clothes | Back | Any | Homeless people, developing countries |

| Sarcoptes scabiei mites (scabies) | Vesicles, burrows, nodules, and nonspecific secondary lesions | Interdigital spaces, forearms, breasts, genitalia | Night | Sexually transmitted, households or institutions |

| Ticks | Erythema migrans or ulcer | Potentially anywhere | Asymptomatic | Pet owners or hikers |

| Pyemotes X ventricosus | Comet sign, a linear erythematous macular tract | Under clothes | Any time when inside habitat | People exposed to woodworm contaminated furniture (Pediculoides ventricosus is a woodworm parasite) |

| Spiders | Necrosis (uncommon) | Face and arms | Immediate pain, no itching | Rural living |

* It is difficult to diagnose a bite. Diagnosis relies on an array of arguments, none of which is specific by itself; it is the association of elements that is suggestive. Any arthropod bite can be totally asymptomatic.

From Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, Chosidow O: Bed bug infestation. BMJ 346:f138, 2013.

Clinical Manifestations

The type of reaction that occurs after an arthropod bite depends on the species of insect and the age group and reactivity of the human host. Arthropods may cause injury to a host by various mechanisms, including mechanical trauma, such as the lacerating bite of a tsetse fly; invasion of host tissues, as in myiasis; contact dermatitis, as seen with repeated exposure to cockroach antigens; granulomatous reaction to retained mouthparts; transmission of systemic disease; injection of irritant cytotoxic or pharmacologically active substances, such as hyaluronidase, proteases, peptidases, and phospholipases in sting venom; and induction of anaphylaxis. Most reactions to arthropod bites depend on antibody formation to antigenic substances in saliva or venom. The type of reaction is determined primarily by the degree of previous exposure to the same or a related species of arthropod. When someone is bitten for the first time, no reaction develops. An immediate petechial reaction is occasionally seen. After repeated bites, sensitivity develops, producing a pruritic papule (Fig. 688.1 ) approximately 24 hr after the bite. This is the most common reaction seen in young children. With prolonged, repeated exposure, a wheal develops within minutes after a bite, followed 24 hr later by papule, vesicle, or bullae formation. By adolescence or adulthood, only a wheal may form, unaccompanied by the delayed papular reaction. Thus, adults in the same household as affected children may be unaffected. Ultimately, as a person becomes insensitive to the bite, no reaction occurs at all. This stage of nonreactivity is maintained only as long as the individual continues to be bitten regularly. Individuals in whom papular urticaria develops are in the transitional phase between development of a primarily delayed papular reaction and development of an immediate urticarial reaction.

Arthropod bites may occur as solitary, numerous, or profuse lesions, depending on the feeding habits of the perpetrator. Fleas tend to sample their host several times within a small localized area, whereas mosquitoes tend to attack a host at more randomly scattered sites. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions to insect bites—the predominant lesions in the young and uninitiated—are characterized by firm, persistent papules that may become hyperpigmented and are often excoriated and crusted. Pruritus may be mild or severe, transient or persistent. A central punctum is usually visible but may disappear as the lesion ages or is scratched. The immediate hypersensitivity reaction is characterized by an evanescent, erythematous wheal. If edema is marked, a tiny vesicle may surmount the wheal. Certain beetles produce bullous lesions through the action of cantharidin, and various insects, including beetles and spiders, may cause hemorrhagic nodules and ulcers. Bites on the lower extremities are more likely to be severe or persistent or become bullous than those located elsewhere. Complications of arthropod bites include development of impetigo, folliculitis, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and severe anaphylactic hypersensitivity reactions, particularly after the bite of certain hymenopterans. The histopathologic changes are variable, depending on the arthropod, the age of the lesion, and the reactivity of the host. Acute urticarial lesions tend to show central vesiculation in which eosinophils are numerous. Papules most commonly show dermal edema and a mixed superficial and deep perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, often including a number of eosinophils. At times, however, the dermal cellular infiltrate is so dense that a lymphoma is suspected. Many young children demonstrate extensive dermal but nonerythematous, nontender edema in response to mosquito bites (Skeeter syndrome ), which responds to oral antihistamines; this must be distinguished from cellulitis, which tends to be painful, tender, and red. Retained mouthparts may stimulate a foreign body type of granulomatous reaction.

Papular urticaria occurs principally in the first decade of life. It may occur at any time of the year. The most common culprits are species of fleas, mites, bedbugs, gnats, mosquitoes, chiggers, and animal lice. Individuals with papular urticaria have predominantly transitional lesions in various stages of evolution between delayed-onset papules and immediate-onset wheals. The most characteristic lesion is an edematous, red-brown papule (Fig. 688.2 ). An individual lesion frequently starts as a wheal that, in turn, is replaced by a papule. A given bite may incite an id reaction at distant sites of quiescent bites in the form of erythematous macules, papules, or urticarial plaques. After a season or two, the reaction progresses from a transitional to a primarily immediate hypersensitivity urticarial reaction.

One of the most commonly encountered arthropod bites is that resulting from human, cat, or dog fleas (family Pulicidae ). Eggs, which are generally laid in dusty areas and cracks between floorboards, give rise to larvae that then form cocoons. The cocoon stage can persist for up to 1 yr, and the flea emerges in response to vibrations from footsteps, accounting for the assaults that frequently befall the new owners of a recently reopened dwelling. Adult dog fleas can live without a blood meal for approximately 60 days. Attacks from fleas are more likely to occur when the fleas do not have access to their usual host; cat or dog fleas are more voracious and problematic when one visits an area frequented by the pet than when the pet is encountered directly. Flea bites tend to be grouped in lines or irregular clusters on the lower extremities. Fleas are often not seen on the body of a pet. Diagnosis of flea bites is aided by examination of debris from the animal's bedding material. The debris is collected by shaking the bedding into a plastic bag and examining the contents for fleas or their eggs, larvae, or feces.

Treatment

Treatment is directed at alleviation of pruritus by oral antihistamines and cool compresses. Potent topical corticosteroids are helpful. Topical antihistamines are potent immunologic sensitizers and have no role in the treatment of insect bite reactions. A short course of systemic steroids may be helpful if many severe reactions occur, particularly around the eyes. Insect repellents containing N,N -diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET) may afford moderate protection against mosquitoes, fleas, flies, chiggers, and ticks, but are relatively ineffective against wasps, bees, and hornets. DEET must be applied to exposed skin and clothing to be effective. The most effective protection against mosquitoes, the human body louse, and other blood-feeding arthropods is the use of DEET and permethrin-impregnated clothing. However, these measures are not effective against the phlebotomine sand fly, which transmits leishmaniasis. Because of the potential for toxicity, the lowest effective DEET dose should be selected. Additional insect repellents include picaridin (flies, mosquitoes, chiggers, ticks), IR3535 (mosquitoes), oil of lemon, eucalyptus (mosquitoes), and citronella (mosquitoes). Table 688.2 lists methods to eliminate bed bugs.

An effort should be made to identify and eradicate the etiologic agent. Pets should be carefully inspected. Crawl spaces, eaves, and other sites of the house or outbuildings frequented by animals and birds should be decontaminated, and baseboard crevices, mattresses, rugs, furniture, and animal sleeping quarters should be decontaminated. Agents that are effective for ridding the home of fleas include lindane, pyrethroids, and organic thiocyanates. Flea-infested pets may be treated with powders containing rotenone, pyrethroids, Malathion, or methoxychlor. Lufenuron, an agent that prevents fleas from reproducing, is effective for animals in oral and injectable formulations. Fipronil is effective as a topical agent for the prevention of flea infestation.

Bibliography

Arthropod Bites

Alpern JD, Dunlop SJ, Dolan BJ, et al. Personal protection measures against mosquitoes, ticks, and other arthropods. Med Clin North Am . 2016;100(2):303–316.

Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ . 2013;346:f138.

Hernandez RG, Cohen BA. Insect bite-induced hypersensitivity and the SCRATCH principles: a new approach to papular urticaria. Pediatrics . 2006;118:e189–e196.

Juckett G. Arthropod bites. Am Fam Physician . 2013;88(12):841–847.

Langley EW, Gigante J. Anaphylaxis, urticaria, and angioedema. Pediatr Rev . 2013;34(6):247–257.

The Medical Letter. Insect repellents. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2012;54:75–76.

Scabies

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Scabies is caused by burrowing and release of toxic or antigenic substances by the female mite Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis . The most important factor that determines spread of scabies is the extent and duration of physical contact with an affected individual. Children and sexual partners of affected individuals are most at risk. Scabies is transmitted only rarely by fomites because the isolated mite dies within 2-3 days.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

An adult female mite measures approximately 0.4 mm in length, has 4 sets of legs, and has a hemispheric body marked by transverse corrugations, brown spines, and bristles on the dorsal surface. A male mite is approximately half her size and is similar in configuration. After impregnation on the skin surface, a gravid female exudes a keratolytic substance and burrows into the stratum corneum, often forming a shallow well within 30 min. She gradually extends this tract by 0.5-5.0 mm/24 hr along the boundary with the stratum granulosum. She deposits 10-25 oval eggs and numerous brown fecal pellets (scybala) daily. When egg laying is completed, in 4-5 wk, she dies within the burrow. The eggs hatch in 3-5 days, releasing larvae that move to the skin surface to molt into nymphs. Maturity is achieved in approximately 2-3 wk. Mating occurs, and the gravid female invades the skin to complete the life cycle.

Clinical Manifestations

In an immunocompetent host, scabies is frequently heralded by intense pruritus, particularly at night (Table 688.3 ). The first sign of the infestation often consists of 1-2 mm red papules, some of which are excoriated, crusted, or scaling. Threadlike burrows are the classic lesion of scabies (Figs. 688.3 and 688.4 ) but may not be seen in infants. In infants, bullae and pustules are relatively common. The eruption may also include wheals, papules, vesicles, and a superimposed eczematous dermatitis (Fig. 688.5 ). The palms, soles, and scalp are often affected. In older children and adolescents, the clinical pattern is similar to that in adults, in whom preferred sites are the interdigital spaces, wrist flexors, anterior axillary folds, ankles, buttocks, umbilicus and belt line, groin, genitals in men, and areolas in women. The head, neck, palms, and soles are generally spared. Infants will often have a diffuse eczematous eruption that will involve the scalp, neck, and face. Red-brown nodules, most often located in covered areas such as the axillae, groin, and genitals, predominate in the less common variant called nodular scabies. Additional clues include facial sparing, affected family members, poor response to topical antibiotics, and transient response to topical steroids. Untreated, scabies may lead to eczematous dermatitis, impetigo, ecthyma, folliculitis, furunculosis, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and id reaction. Glomerulonephritis has developed in children from streptococcal impetiginization of scabies lesions. In some tropical areas, scabies is the predominant underlying cause of pyoderma. A latent period of approximately 1 mo follows an initial infestation. Thus, itching may be absent and lesions may be relatively inapparent in contacts who are asymptomatic carriers. However, on reinfestation, reactions to mite antigens are noted within hours.

Table 688.3

Different Presenting Forms of Scabies

| PRESENTING FORMS OF SCABIES | SPECIFIC HIGH-RISK POPULATIONS | CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS | LIMITED DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic scabies (scabies vulgaris) | Infants and children; sexually active adults; men who have sex with men | Intense generalized pruritus, worse at night; inflammatory pruritic papules localized to finger webs, flexor aspects of wrists, elbows, axillae, buttocks, genitalia, female breasts; lesions and pruritus spare the face, head, and neck; secondary lesions include eczematization, excoriation, impetigo | Dermatitis herpetiformis, drug reactions, eczema, pediculosis corporis, lichen planus, pityriasis rosea |

| Scalp scabies | Infants and children; institutionalized older adults; AIDS patients; patients with preexisting crusted scabies | Atypical crusted papular lesions of the scalp, face, palms, and soles | Dermatomyositis, ringworm, seborrheic dermatitis |

| Crusted scabies (Norwegian scabies, scabies norvegica, scabies crustosa) | Institutionalized older adults; institutionalized developmentally disabled (Down syndrome); homeless, especially HIV-positive; all immunocompromised patients, particularly those with AIDS or positive for HIV or HTLV-1; transplant recipients; patients on prolonged systemic corticosteroids and chemotherapy | Psoriasiform hyperkeratotic papular lesions of the scalp, face, neck, hands, feet, with extensive nail involvement; eczematization and impetigo common | Contact dermatitis, drug reactions, eczema, erythroderma, ichthyosis, psoriasis |

| Nodular scabies | Sexually active adults; men who have sex with men; HIV-positive men > HIV-positive women | Violaceous pruritic nodules localized to male genitalia, groin, axillae, representing hypersensitivity reaction to mite antigens | Acropustulosis, atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, lupus erythematosus, lymphomatoid papulosis, papular urticaria, necrotizing vasculitis, secondary syphilis |

HTLV-1, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1.

From Bennett JE, Blaser MJ, Dolin R, et al: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases , ed 8, Philadelphia, 2015, Elsevier/Saunders, Table 295.1, p 3252.

Differential Diagnosis

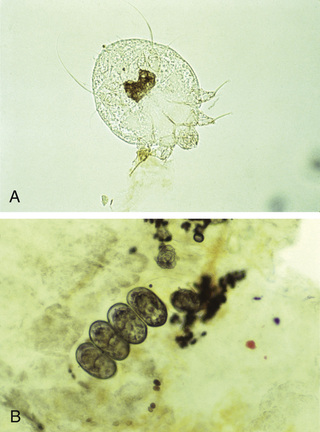

Differential diagnosis of scabies can often be made clinically but is confirmed by microscopic identification of mites (Fig. 688.6A ), ova, and scybala (see Fig. 688.6B ) in epithelial debris. Scrapings most often test positive when obtained from burrows or fresh papules. A reliable method is application of a drop of mineral oil on the selected lesion, scraping of it with a No. 15 blade, and transferring the oil and scrapings to a glass slide.

The differential diagnosis depends on the types of lesions present. Burrows are virtually pathognomonic for human scabies. Papulovesicular lesions are confused with papular urticaria, canine scabies, chickenpox, viral exanthems, drug eruptions, dermatitis herpetiformis, and folliculitis. Eczematous lesions may mimic atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis, and the less common bullous disorders of childhood may be suspected in infants with predominantly bullous lesions. Nodular scabies is frequently misdiagnosed as urticaria pigmentosa and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. The histopathologic appearance of nodular scabies, consisting of a deep, dense, perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and atypical mononuclear cells, may mimic malignant lymphoid neoplasms.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for scabies is permethrin 5% cream (Elimite) applied to the entire body from the neck down, with particular attention to intensely involved areas, which is also standard therapy (Table 688.4 ). Scabies is frequently found above the neck in infants (younger than 2 yr old), necessitating treatment of the scalp. The medication is left on the skin for 8-12 hr and should be reapplied in 1 wk for another 8-12 hr period. Additional therapies include sulfur ointment 5–10%, and crotamiton 10% lotion or cream. Lindane 1% lotion or cream should only be used as an alternative therapy, given risk of systemic toxicity. For severe infestations or in immunocompromised patients, oral ivermectin 200 µg/kg per dose given orally for 2 doses, 2 wk apart can be used (off-label use). Single dose ivermectin (200 µg/kg) has also been effective in immunocompetent patients with improvement (cure) noted in 60% at 2 wk and 89% at 4 wk after treatment (see Table 688.4 ).

Table 688.4

Currently Recommended Treatment for Scabies

| SCABICIDES | FDA APPROVED? | PREGNANCY CATEGORY* | DOSING SCHEDULE | SAFETY PROFILE | CONTRAINDICATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% Permethrin cream (Actin, Nix, Elimite) | Yes | B | Apply from neck down; wash off after 8-14 hr; good residual activity, but second application recommended after 1 wk | Excellent; itching and stinging on application | Prior allergic reactions; infants <2 mo of age; breast-feeding |

| 1% Lindane lotion or cream | Yes | B | Apply 30-60 mL from neck down; wash off after 8-12 hr; no residual activity; increasing drug resistance | Potential for central nervous system toxicity from organochloride poisoning, usually manifesting as seizures, with overapplication and ingestions | Preexisting seizure disorder; infants and children <6 mo of age; pregnancy; breastfeeding |

| 10% Crotamiton cream or lotion (Eurax) | Yes | C | Apply from neck down on 2 consecutive nights; wash off 24 hr after second application | Excellent; not very effective; exacerbates pruritus | None |

| 2–10% Sulfur in petrolatum ointments | No | C | Apply for 2-3 days, then wash | Excellent; not very effective | Preexisting sulfur allergy |

| 10–25% Benzoyl benzoate lotion | No | None | Two applications for 24 hr with 1-day to 1-wk interval | Irritant; exacerbates pruritus; can induce contact irritant dermatitis and pruritic cutaneous xerosis | Preexisting eczema |

| 0.5% Malathion lotion (Ovide), 1% malathion shampoo (unavailable in the United States) | No | B | 95% ovicidal; rapid (5 min) killing; good residual activity; increasing drug resistance | Flammable 78% isopropyl alcohol vehicle stings eyes, skin, mucosa; increasing drug resistance; organophosphate poisoning risk with overapplication and ingestions | Infants and children <6 mo of age; pregnancy; breast-feeding |

| Ivermectin (Stromectol) | Yes | C | 200-µg/kg single PO dose, may be repeated in 14-15 days; not ovicidal, second dose on day 14 or 15 highly recommended; recommended for endemic or epidemic scabies in institutions and refugee camps | Excellent; may cause nausea and vomiting; take on empty stomach with water | Safety in pregnancy uncertain; probably safe during breastfeeding; not recommended for children younger than 5 yr of age or weighing <15 kg |

* U.S. Food and Drug Administration safety in pregnancy categories: A, safety established; B, presumed safe; C, uncertain safety; D, unsafe; X, highly unsafe.

From Bennett JE, Blaser MJ, Dolin R, et al: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases , ed 8, Philadelphia, 2015, Elsevier/Saunders, Table 295.2, p 3253.

Transmission of mites is unlikely more than 24 hr after treatment. Pruritus, which is a result of hypersensitivity to mite antigens, may persist for a number of days to weeks, and may be alleviated by a topical corticosteroid preparation. If pruritus persists for >2 wk after treatment and new lesions are occurring, the patient should be reexamined for mites. Nodules are extremely resistant to treatment and may take several months to resolve. The entire family should be treated, as should caretakers of the infested child. Clothing, bed linens, and towels should be washed in hot water and dried using high heat. Clothing or other items (e.g., stuffed animals) that cannot be washed may be dry cleaned or stored in bags for 3 days to 1 wk, as the mite will die when separated from the human host.

Norwegian (Crusted) Scabies

The Norwegian variant of human scabies is highly contagious and occurs mainly in individuals who are cognitively and physically debilitated, particularly those who are institutionalized and those with Down syndrome; in patients with poor cutaneous sensation (leprosy, spina bifida); in patients who have severe systemic illness (leukemia, diabetes); and in immunosuppressed patients (HIV infection). Affected individuals are infested by a myriad of mites that inhabit the crusts and exfoliating scales of the skin and scalp (Fig. 688.7 ). The nails may become thickened and dystrophic. The subungual debris is densely populated by mites. The infestation is often accompanied by generalized lymphadenopathy and eosinophilia. There is massive orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous interspersed mites, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, foci of spongiosis, and neutrophilic abscesses. Norwegian scabies is thought to represent a deficient host immune response to the organism. Management is difficult, requiring scrupulous isolation measures, removal of the thick scales, and repeated but careful applications of permethrin 5% cream. Ivermectin (200-250 µg/kg) has been used successfully as single-dose therapy in refractory cases, particularly in HIV-infected patients. A second dose may be needed a week later. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved this agent for the treatment of scabies.

Canine Scabies

Canine scabies is caused by S. scabiei var. canis, the dog mite that is associated with mange. The eruption in humans, which is most frequently acquired by cuddling an infested puppy, consists of tiny papules, vesicles, wheals, and excoriated eczematous plaques. Burrows are not present because the mite infrequently inhabits human stratum corneum. The rash is pruritic and has a predilection for the arms, chest, and abdomen, the usual sites of contact with dogs. Onset is sudden and usually follows exposure by 1-10 days, possibly resulting from development of a hypersensitivity reaction to mite antigens. Recovery of mites or ova from scrapings of human skin is rare. The disease is self-limited because humans are not a suitable host. Bathing and changing clothes are generally sufficient. Removal or treatment of the infested animal is necessary. Symptomatic therapy for itching is helpful. In rare cases in which mites are demonstrated in scrapings from an affected child, they can be eradicated by the same measures applicable to human scabies.

Other Types of Scabies

Other mites that occasionally bite humans include the chigger or harvest mite (Eutrombicula alfreddugesi), which prefers to live on grass, shrubs, vines, and stems of grain. Larvae have hooked mouthparts, which allow the chigger to attach to the skin, but not to burrow, to obtain a blood meal, most commonly on the lower legs. Avian mites may affect those who come into close contact with chickens or pet gerbils. Humans may occasionally be assaulted by avian mites that have infested a nest outside a window, an attic, heating vents, or an air conditioner. The dermatitis is variable, including grouped papules, wheals, and vesicular lesions on the wrists, neck, breasts, umbilicus, and anterior axillary folds. A prolonged investigation is often undertaken before the cause and source of the dermatitis are discovered.

Bibliography

Scabies

Boralevi F, Diallo A, Miquel J, et al. Clinical phenotype of scabies by age. Pediatrics . 2014;133:e910–e916.

Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med . 2010;362:717–725.

Goldust M, Rezaee E. Hemayat s. Treatment of scabies: comparison of permethrin 5% versus ivermectin. J Dermatol . 2012;39:545–547.

Guergué Diaz de Cerio O, del Rosario Gonzáles Hermosa M, Ballestero Díez M. Bullous scabies in a 5-year-old-child. J Pediatr . 2016;179:270.

Mohebbipour A, Saleh P, Goldust M, et al. Comparison of oral ivermectin vs. lindane lotion 1% for the treatment of scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol . 2013;38:719–723.

Mounsey KE, McCarthy KS. Treatment and control of scables. Curr Opin Infect Dis . 2013;26(2):133–139.

Paller AS, Mancini AJ, Hurwitz S. Hurwitz clinical pediatric dermatology: a textbook of skin disorders of childhood and adolescence . ed 4. Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2011:416–435.

Panahi Y, Poursaleh Z, Goldust M. The efficacy of topical and oral ivermectin in the treatment of human scabies. Ann Parasitol . 2015;61(1):11–16.

Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med . 2015;373(24):2305–2313.

Strong M, Johnstone PW. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2007;(18) [CD000320].

Thompson MJ, Engelman D, Gholam K, et al. Systematic review of the diagnosis of scabies in therapeutic trials. Clin Exp Dermatol . 2017;42(5):481–487; 10.1111/ced.13152 [Epub 2017 May 29].

Pediculosis

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Three types of lice are obligate parasites of the human host: body or clothing lice (Pediculus humanus corporis), head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis), and pubic or crab lice (Phthirus pubis). Only the body louse serves as a vector of human disease (typhus, trench fever, relapsing fever). Body and head lice have similar physical characteristics. They are approximately 2-4 mm in length. Pubic lice are only 1-2 mm in length and are greater in width than length, giving them a crab-like appearance. Female lice live for approximately 1 mo and deposit 3-10 eggs daily on the human host. However, body lice generally lay eggs in or near the seams of clothing. The ova or nits are glued to hairs or fibers of clothing but not directly on the body. Ova hatch in 1-2 wk and require another week to mature. Once the eggs hatch, the nits remain attached to the hair as empty sacs of chitin. Freshly hatched larvae die unless a meal is obtained within 24 hr and every few days thereafter. Both nymphs and adult lice feed on human blood, injecting their salivary juices into the host and depositing their fecal matter on the skin. Symptoms of infestation do not appear immediately but develop as an individual becomes sensitized. The hallmark of all types of pediculosis is pruritus.

Pediculosis corporis is rare in children except under conditions of poor hygiene, especially in colder climates when the opportunity to change clothes on a regular basis is lacking. The parasite is transmitted mainly on contaminated clothing or bedding. The primary lesion is a small, intensely pruritic, red macule or papule with a central hemorrhagic punctum, located on the shoulders, trunk, or buttocks. Additional lesions include excoriations, wheals, and eczematous, secondarily infected plaques. Massive infestation may be associated with constitutional symptoms of fever, malaise, and headache. Chronic infestation may lead to “vagabond's skin,” which manifests as lichenified, scaling, hyperpigmented plaques, most commonly on the trunk. Lice are found on the skin only transiently when they are feeding. At other times, they inhabit the seams of clothing. Nits are attached firmly to fibers in the cloth and may remain viable for up to 1 mo. Nits hatch when they encounter warmth from the host's body when the clothes are worn again. Therapy consists of improved hygiene and hot water laundering of all infested clothing and bedding. A uniform temperature of 65°C (149°F), wet or dry, for 15-30 min kills all eggs and lice. Alternatively, eggs hatch and nymphs starve if clothing is stored for 2 wk at 23.9-29.4°C (75-85°F).

Pediculosis capitis is an intensely pruritic infestation of lice in the scalp hair. It is the most common form of lice to affect children, in particular those between the ages of 3 and 12 yr. Fomites and head-to-head contact are important modes of transmission. In summer months in many areas of the United States and in the tropics at all times of the year, shared combs, brushes, or towels have a more important role in louse transmission. Translucent 0.5 mm eggs are laid near the proximal portion of the hair shaft and become adherent to one side of the shaft (Fig. 688.8 ). A nit cannot be moved along or knocked off the hair shaft with the fingers. Secondary pyoderma, after trauma from scratching, may result in matting together of the hair and cervical and occipital lymphadenopathy. Hair loss does not result from pediculosis but may accompany the secondary pyoderma. Head lice are a major cause of numerous pyodermas of the scalp, particularly in tropical environments. Lice are not always visible, but nits are detectable on the hairs, most commonly in the occipital region and above the ears, rarely on beard or pubic hair. Dermatitis may also be noted on the neck and pinnae. An id reaction, consisting of erythematous patches and plaques, may develop, particularly on the trunk. Head lice rarely infest African Americans and this is possibly related to the diameter, shape, or twisted nature of their hair shafts (which makes grasping of the shaft more difficult for the louse).

In the cases of resistance (which is common) of head lice to pyrethroids, malathion 0.5% in isopropanol is the treatment of choice and should be applied to dry hair until hair and scalp are wet, and left on for 12 hr. A second application, 7-9 days after the initial treatment may be necessary. This product is flammable, so care should be taken to avoid open flames. Malathion, like lindane shampoo, is not indicated for use in neonates and infants; however, additional approved therapies include spinosad (if >6 mo), benzyl alcohol lotion (if >6 mo), and ivermectin for difficult-to-treat head lice (Table 688.5 ). All household members should be treated at the same time. Nits can be removed with a fine-toothed comb after application of a damp towel to the scalp for 30 min. Clothing and bed linens should be laundered in very hot (>130°F) water and then dried for at least 10 min at the highest setting or dry-cleaned; brushes and combs should be discarded or coated with a pediculicide for 15 min and then thoroughly cleaned in boiling water. If the object cannot be washed, it can be sealed in a plastic bag for 48 hr. Children may return to school after the initial treatment.

Table 688.5

| DRUG | RESISTANCE | FDA-APPROVED LOWER AGE OR WEIGHT LIMIT | DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION | COST* /SIZE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin 0.5% lotion–Sklice (Arbor) | No | 6 mo | Apply to dry hair and scalp for 10 min, then rinse † | $297.60/4 oz |

| Ivermectin tablets ‡ –Stromectol (MSD) | No | 15 kg § | 200-400 µg/kg PO once; repeat 7-10 days later | $9.30 || |

| Spinosad 0.9% suspension–Natroba (ParaPro) | No | 6 mo | Apply to dry hair for 10 min, then rinse; repeat 7 days later if necessary ¶ | $246.10/4 oz |

| Benzyl alcohol 5% lotion–Ulesfia (Lachlan) | No | 6 mo | Apply to dry hair for 10 min, then rinse; repeat 7 days later** | $181.30/8 oz |

| Pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide shampoo †† –Generic Rid (Bayer) | Yes | 2 yr | Apply to dry hair for 10 min, then shampoo; repeat 7-10 days later |

$15.00/8 oz ‡‡ $20.00/8 oz ‡‡ |

| Permethrin 1% creme rinse †† –Generic Nix (Insight) | Yes | 2 mo | Apply to shampooed, towel-dried hair for 10 min, then rinse; repeat 7 days later |

$18.00/4 oz ‡‡ $21.00/4 oz ‡‡ |

| Malathion 0.5% lotion–Generic Ovide (Taro) | Not in the United States | 6 yr §§ | Apply to dry hair for 8-12 hr, then shampoo; repeat 7-9 days later if necessary ||||, ¶¶ |

$221.70/2 oz $246.40/2 oz |

* Approximate WAC for the indicated size. WAC represents a published catalogue or list price and may not represent an actual transactional price. Source: AnalySource Monthly. November 5, 2016. Reprinted with permission by First Databank, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016. www.fdbhealth.com/policies/drug-pricing-policy . Total cost of treatment may vary based on hair length and number of applications required to completely eradicate lice.

† The manufacturer recommends using up to one single-use, 4-oz tube of topical ivermectin lotion per application.

‡ Not FDA approved for treatment of head lice.

§ The safety and effectiveness of oral ivermectin have not been established in children weighing <15 kg.

|| Cost of two 3 mg tablets (one dose for a 30-kg child at the lowest dosage).

¶ The manufacturer recommends using up to one 4 oz (120 mL) bottle of spinosad 0.9% suspension per application.

** The amount of benzoyl alcohol 5% lotion recommended per application depends on hair length.

†† Available without a prescription.

‡‡ Approximate cost according to walgreens.com . Accessed November 10, 2016.

§§ The safety and effectiveness of malathion lotion have not been established in children <6 yr old; it is contraindicated in children <24 mo old.

|||| In clinical trials, patients used a maximum of 2 fl oz of malathion lotion per application.

¶¶ One or two 20 min applications have also been effective (Meinking TL, Vicaria M, Eyerdam DH, et al: Efficacy of a reduced application time of Ovide lotion (0.5% malathion) compared to Nix creme rinse (1% permethrin) for the treatment of head lice. Pediatr Dermatol 21:670–674, 2004.)

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; MSD, Merck Sharp Dohme; WAC, wholesaler acquisition cost or manufacturer's published price to wholesalers.

From The Medical Letter: Drugs for head lice. Med Lett Drugs Ther 58:150–152, 2016.

Pediculosis pubis is transmitted by skin-to-skin or sexual contact with an infested individual; the chance of acquiring the lice with 1 sexual exposure is 95%. The infestation is usually encountered in adolescents, although small children may occasionally acquire pubic lice on the eyelashes. Patients experience moderate to severe pruritus and may develop a secondary pyoderma from scratching. Excoriations tend to be shallow, and the incidence of secondary infection is lower than in pediculosis corporis. Maculae ceruleae are steel-gray spots, usually <1 cm in diameter, which may appear in the pubic area and on the chest, abdomen, and thighs. Oval translucent nits, which are firmly attached to the hair shafts, may be visible to the naked eye or may be readily identified by a hand lens or by microscopic examination (see Fig. 688.8 ). Grittiness, as a result of adherent nits, may sometimes be detected when the fingers are run through infested hair. Adult lice are more difficult to detect than head or body lice because of their lower level of activity and smaller, translucent bodies. Because pubic lice occasionally may wander or may be transferred to other sites on fomites, terminal hair on the trunk, thighs, axillary region, beard area, and eyelashes should be examined for nits. The coexistence of other venereal diseases should be considered. Treatment with a 10-min application of a pyrethrin preparation is usually effective. Retreatment may be required in 7-10 days. Infestation of eyelashes is eradicated by petrolatum applied 3-5 times per 24 hr for 8-10 days. Clothing, towels, and bed linens may be contaminated with nit-bearing hairs and should be thoroughly laundered or dry-cleaned.

Bibliography

Pediculosis

Ameen M, Arenas R, Villanueva-Reyes J, et al. Oral ivermectin for treatment of pediculosis capitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2010;29(11):991–993.

Burgess IF, Brunton ER, Burgess NA. Single application of 4% dimethicone liquid gel versus two applications of 1% permethrin crème rinse for treatment of head louse infestation: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Dermatol . 2013;13(5):1–7.

Chosidow O, Giraudeau B, Cottrell J, et al. Oral ivermectin versus malathion lotion for difficult-to-treat head lice. N Engl J Med . 2010;362(10):896–904.

Deeks LS, Naunton M, Currie MJ, et al. Topical ivermectin 0.5% lotion for treatment of head lice. Ann Pharmacother . 2013;47(9):1161–1167.

Devore CD, Schutze GE, et al. Head lice. Pediatrics . 2015;135(5):e1355–e1365.

Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med . 2010;362(8):717–724.

Frankowski BL, Bocchini JA Jr. Council on school health and committee on infectious diseases: clinical report: head lice. Pediatrics . 2010;126:392–403.

Friedmeier H. Treatment of pediculosis capitis: a critical appraisal of the current literature. Am J Clin Dermatol . 2014;15(5):401–412.

Hazan L, Berg JE, Bowman JP, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of 0.5% ivermectin lotion for head louse infestations. Pediatr Dermatol . 2013;30:323–328.

Lebwohl M, Clark L, Levitt J. Therapy for head lice based on life cycle, resistance, and safety considerations. Pediatrics . 2007;119:965–974.

The Medical Letter. Drugs for head lice. Med Lett Drugs Ther . 2016;58(1508):150–152.

Meinking TL, Villar ME, Vicaria M, et al. The clinical trials supporting benzyl alcohol lotion 5% (Ulesfia): a safe and effective topical treatment for head lice (pediculosis humanus capitis). Pediatr Dermatol . 2010;27(1):19–24.

Seabather's Eruption

Daren A. Diiorio, Stephen R. Humphrey

Seabather's eruption is a severely pruritic dermatosis of inflammatory papules that develops within about 12 hr of bathing in saltwater, primarily on body sites that were covered by a bathing suit. The eruption has been described primarily in connection with bathing in the waters of Florida and the Caribbean. Lesions, which may include pustules, vesicles, and urticarial plaques, are more numerous in individuals who keep their bathing suits on for an extended period after leaving the water. The eruption may be accompanied by systemic symptoms of fatigue, malaise, fever, chills, nausea, and headache; in one large series, ~40% of children younger than 16 yr of age had fever. Duration of the pruritus and skin eruption is 1-2 wk. Lesions consist of a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils. The eruption appears to be due to an allergic hypersensitivity reaction to venom from larvae of the thimble jellyfish (Linuche unguiculata). Treatment is largely symptomatic. Potent topical corticosteroids have been shown to provide relief to some patients.