The Upper Limb

Robert B. Carrigan

Shoulder

The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint similar to the hip; however, there are several anatomic differences between the two. The shoulder is a very shallow joint compared with the hip and is thus more prone to dislocation. In addition, the shoulder range of motion (ROM) is much greater than that of the hip. This is due to the size of the humeral head relative to the glenoid, as well as to the presence of scapulothoracic motion. The shoulder positions the hand along the surface of a theoretical sphere in space, with its center at the glenohumeral joint.

Sprengel Deformity

Sprengel deformity, or congenital elevation of the scapula, is a disorder of development that involves a high scapula and limited scapulothoracic motion. The scapula originates in early embryogenesis at a level posterior to the 4th cervical vertebra, but it descends during development to below the 7th cervical vertebra. Failure of this descent, either unilateral or bilateral, is the Sprengel deformity. The severity of the deformity depends on the location of the scapula and associated anomalies. The scapula in mild cases is simply rotated, with a palpable or visible bump corresponding to the superomedial corner of the scapula in the region of the trapezius muscle. Function is generally good. In moderate cases, the scapula is higher on the neck and connected to the spine with an abnormal omovertebral ligament or even bone. Shoulder motion, particularly abduction, is limited. In severe cases, the scapula is small and positioned on the posterior neck, and the neck may be webbed. The majority of patients have associated anomalies of the musculoskeletal system, especially in the spine, making spinal evaluation important.

Treatment

In mild cases, treatment is generally unnecessary, although a prominent and unsightly superomedial corner of the scapula can be excised. In more severe cases, surgical repositioning of the scapula with rebalancing of parascapular muscles can significantly improve both function and appearance.

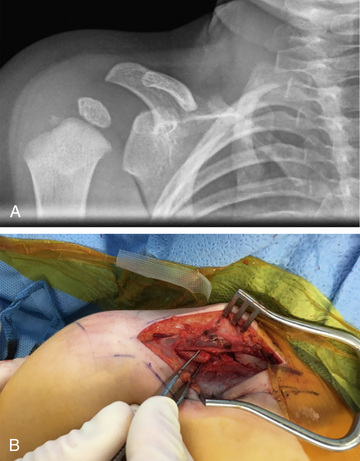

Congenital Pseudoarthrosis of the Clavicle

The clavicle is a tubular S-shaped bone that articulates with the sternum and acromion. It acts as a strut to keep the shoulder from protracting forward. Congenital pseudoarthrosis of the clavicle is a failure of the two primary ossification centers of the clavicle to fuse during embryogenesis (Fig. 701.1 ). The condition presents exclusively on the right side and may be confused for an acute clavicle fracture sustained during birth. A thorough history and physical exam will help to distinguish between the two conditions. Both a birth-related clavicle fracture and a congenital pseudoarthrosis present with a bump or prominence over the midclavicle. The child with a birth-related clavicle fracture will have tenderness to palpation on exam; the parents may also report that the child is fussy with feeding and changing. Congenital pseudoarthrosis of the clavicle will be painless on exam. Radiographically the congenital pseudoarthrosis clavicle will have to rounded edges at the midportion with signs of hypertrophy.

Treatment

Treatment of congenital pseudoarthrosis of the clavicle is varied, without a clear consensus. Some advocate for operative treatment, citing concerns for vascular and neurologic impingement of the clavicle on the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels, others advocate for observation and only considering operative treatment in symptomatic cases.

The operative treatment of congenital pseudoarthrosis of the clavicle consists of opening the pseudoarthrosis site, preserving the periosteum, debriding the hypertrophic ends, bone grafting, and stabilization.

Elbow

The elbow is the most congruent joint in the body. The stability of the elbow is imparted via this bony congruity, as well as through the medial and radial collateral ligaments. Where the shoulder positions the hand along the surface of a theoretical sphere, the elbow positions the hand within that sphere. The elbow allows extension and flexion through the ulnohumeral articulation and pronation and supination through the radiocapitellar articulation.

Panner Disease

Panner disease is a disruption of the blood flow to the articular cartilage and subchondral bone to the capitellum (Fig. 701.2 ). It typically occurs in boys between the ages of 5 and 13 yr. Presenting symptoms include lateral elbow pain, loss of motion, and, in advanced cases, mechanical symptoms of the elbow (loose bodies).

The mechanism of injury can be impaction or overloading of the joint, as seen with sports such as gymnastics and baseball. It can also be idiopathic. Radiographs of the elbow may be normal, but they may also show a small lucency within the subchondral bone of the capitellum. MRI is the study of choice to evaluate a suspected capitellar lesion. MRI can demonstrate the extent of the involvement in the subchondral bone, as well as the integrity of the cartilage of the articular surface.

Treatment

Treatment is typically conservative. Rest, activity modification, and patient education are initial treatment options. In cases where the articular cartilage fragments and loose bodies form, arthroscopy of the elbow is warranted to remove the loose bodies. When the cartilage defect in the capitellum is large and symptomatic, procedures to restore the articular cartilage may be considered. These procedures include drilling of the subchondral bone (microfracture) to promote scar cartilage and osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS).

Radial Longitudinal Deficiency

Radial longitudinal deficiency of the forearm comprises a spectrum of conditions and diseases that result in hypoplasia or absence of the radius (Table 701.1 ). This process was formerly referred to as radial club hand, but the name has been changed to radial longitudinal deficiency, which better characterizes the condition. Clinical characteristics consist of a small, shortened limb with the hand and wrist in excessive radial deviation. Partial or complete absence of the radial structures of the forearm and hand are observed (Fig. 701.3 ).

Table 701.1

From Trumble T, Budoff J, Cornwall R, editors: Core knowledge in orthopedics: hand, elbow, shoulder , Philadelphia, 2005, Elsevier, p 425.

Radial longitudinal deficiency has been classified into four types according to Bayne and Klug (Table 701.2 ). Radial longitudinal deficiency can be associated with other syndromes such as Holt-Oram and Fanconi anemia (see Chapter 495 ).

Table 701.2

Adapted from Bayne LG, Klug MS: Long-term review of the surgical treatment of radial deficiencies. J Hand Surg Am 12(2):169–179, 1987.

Treatment

The goals for the treatment of radial longitudinal deficiency include centralizing the hand and wrist on the forearm, balancing the wrist, and maintaining appropriate thumb and digital motion. Shortly after birth, parents are encouraged to passively stretch the wrist and hand to elongate the contracted radial soft tissues. Serial casting and splinting are ineffective at this time, due to the small size of the arm.

Surgery for correction of the wrist deformity remains controversial. Historically for children with good elbow motion, centralization of the wrist on the forearm was performed. However, recurrence of the deformity was often observed, leading some surgeons to abandon this procedure.

When considering a centralization procedure, the preoperative plan begins with careful examination of the patient; considerations in regard to thumb and elbow function must be made before surgery. The surgery typically occurs when the child is 1 yr of age. Correction of the radial deviation, as well as centralization of the wrist, can be accomplished with a variety of different surgical techniques. These techniques include open release, capsular reefing, and tendon rebalancing. External fixation techniques have also been described.

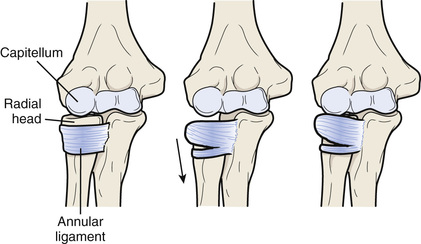

Nursemaid Elbow

Nursemaid elbow is a subluxation of a ligament rather than a subluxation or dislocation of the radial head. The proximal end of the radius, or radial head, is anchored to the proximal ulna by the annular ligament, which wraps like a leash from the ulna, around the radial head, and back to the ulna. If the radius is pulled distally, the annular ligament can slip proximally off the radial head and into the joint between the radial head and the humerus (Fig. 701.4 ). The injury is typically produced when a longitudinal traction force is applied to the arm, such as when a falling child is caught by the hand, or when a child is pulled by the hand. The injury usually occurs in toddlers and rarely occurs in children >5 yr of age. Subluxation of the annular ligament produces immediate pain and limitation of supination. Flexion and extension of the elbow are not limited, and swelling is generally absent. The diagnosis is made by history and physical examination because radiographs are typically normal.

Treatment

The annular ligament is reduced by rotating the forearm into supination while holding pressure over the radial head. A palpable click or clunk can be felt. This maneuver usually provides immediate relief of discomfort and recovery of active supination. Immobilization is not required, but recurrent annular ligament subluxations can occur, and the parents should avoid activities that apply traction to the elbows. Parents can learn reduction maneuvers for recurrent episodes to avoid trips to the emergency department or pediatrician's office. Recurrent subluxation beyond 5 yr of age is rare. Irreducible subluxations tend to resolve spontaneously, with gradual resolution of symptoms over days to weeks; surgery is rarely indicated.

Wrist

The wrist is composed of the two forearm bones and the eight carpal bones. The wrist allows flexion, extension, and radial and ulnar deviation through the radiocarpal and midcarpal articulations. Pronation and supination occur, at the wrist, through the distal radial ulnar joint. The wrist is a complex joint with numerous ligamentous and soft tissue attachments. Its complex kinematics allow for a generous ROM, but when these kinematics are altered, significant dysfunction can occur.

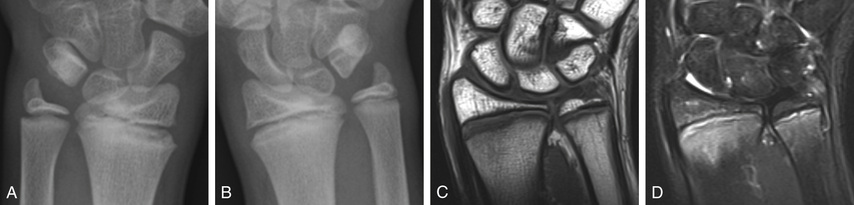

Madelung Deformity

Madelung deformity is a deformity of the wrist that is characterized as radial and palmar angulations of the distal aspect of the radius (Fig. 701.5 ). Growth arrest of the palmar and ulnar aspect of the distal radial physis is the underlying cause of this deformity. Bony physeal lesions and an abnormal radiolunate ligament (Vickers ligament) have been implicated. The deformity can be bilateral and affects girls more than boys.

Treatment

Treatment of Madelung deformity is typically observation. Mild deformities can be observed until skeletal maturity. Moderate to severe deformities that either are painful or limit function may be candidates for surgical intervention. Surgical treatment for Madelung deformity is often motivated by appearance. Patients and their families may be concerned about the palmar angulation of the wrist, as well as the resulting prominent distal ulna.

There are a multitude of surgical options for treating Madelung deformity. For the skeletally immature patient, resection of the tethering soft tissue (Vickers ligament) and physiolysis (fat grafting of any bony lesion seen within the physis) is often the first option. When Madelung deformity is encountered in skeletally mature patients, an osteotomy may be considered. Dorsal closing wedge, dome, and ulnar shortening osteotomies may be used alone or in combination to achieve the desired result.

Long-term considerations of Madelung deformity concern the incongruity of the distal radial ulnar joint and resulting premature arthritis of the joint.

Gymnast's Wrist

Gymnast's wrist refers to the changes observed in the physis of the distal radius in the setting of repetitive stress associated with gymnastics (Fig. 701.6 ). Symptoms include pain with weight bearing, swelling, and loss of motion (mainly wrist extension). The pain is typically mild at first and worsens with time and increased activity. Children will have pain over the distal radial physis on palpation. The child should also be examined for coexisting wrist pathology, including distal radial-ulnar joint instability and triangular fibrocartilage complex tears. Radiographs are often normal but may show chronic changes in the distal radial physis, including widening, sclerosis, and partial physeal arrest. Ulnar positive variance may also be observed because of partial growth arrest of the radius. MRI may be useful to examine the extent of physeal involvement, as well as triangular fibrocartilage complex pathology.

Treatment

Treatment of gymnast's wrist begins with rest. Typically, the child is prohibited from weight-bearing activities for a period of 6 wk, until symptoms resolve. The child may gradually resume his or her routine. If symptoms return during the recovery phase, then rest is reinitiated. It is not uncommon for relapses to occur when returning to competition. This may be difficult for the child and parents to understand because gymnasts and gymnasts’ families are often very motivated to continue their sport. Use of wrist supports or braces may help to limit the amount of force transmitted to the wrist and in turn help with injury prevention.

In cases where significant damage is seen in the distal radius physis, surgery may be indicated to prevent future morphologic changes in the wrist. Surgery may include epiphysiodesis of the radius and ulna, shortening of the ulna, and triangular fibrocartilage complex repair.

Ganglion

As a synovial joint, the wrist articulation is lubricated with synovial fluid, which is produced by the synovial lining of the joint and maintained within the joint by the joint capsule. A defect in the capsule can allow fluid to leak from the joint into the soft tissues, resulting in a ganglion. The term cyst is a misnomer, because this extraarticular collection of fluid does not have its own true lining. The defect in the capsule can occur as a traumatic event, although trauma is rarely a feature of the presenting history. The fluid usually exits the joint in the interval between the scaphoid and lunate, resulting in a ganglion located at the dorsoradial aspect of the wrist. Ganglia can occur at other locations, such as the volar aspect of the wrist, or in the palm as a result of leakage of fluid from the flexor tendon sheaths. Pain is not commonly associated with ganglia in children, and when it is, it is unclear whether the cyst is the cause of the pain. The diagnosis is usually evident on physical examination, especially if the lesion transilluminates. Extensor tenosynovitis and anomalous muscles can mimic ganglion cysts, but radiography or MRI is not routinely required. Ultrasonography is an effective, noninvasive tool to support the diagnosis and reassure the patient and family.

Treatment

Treatment of ganglia may include aspiration, excision, injection, and observation; ultrasound can confirm the diagnosis (AEIOU).

- Aspiration : Simple aspiration of the fluid has a high recurrence rate and is painful for children given the large-bore needle required to aspirate the gelatinous fluid. However, this approach may be reasonable, particularly in older children, to attempt cyst decompression as a less invasive alternative to surgery.

- Excision: Surgical excision, including excision of the stalk connecting the ganglion to its joint of origin, has a high success rate, although the ganglion can recur.

- Injection : Aspiration of the cyst and a simultaneous injection of a corticosteroid is effective in treating recurrence in children.

- Observation: Up to 80% of ganglia in children <10 yr of age resolve spontaneously within 1 yr of being noticed. If the ganglion is painful or bothersome and the child is >10 yr of age, treatment may be warranted.

- Ultrasound: For children's parents who are concerned about the mass and want a radiographic study to confirm the diagnosis, ultrasound is a noninvasive test to confirm the diagnosis.

Hand

The hand and fingers allow for complex and fine manipulations. An intricate balance among extrinsic flexors, extensors, and intrinsic muscles allow these complex motions to occur. Congenital anomalies of the hand and upper extremity rank just behind cardiac anomalies in incidence. Like cardiac anomalies, if they are not properly identified and remedied, they may have long-term consequences.

Camptodactyly

Camptodactyly is a nontraumatic flexion contracture of the proximal interphalangeal joint that is often progressive. The small and ring fingers are most often affected. Bilateralism is observed two thirds of the time. The etiology of camptodactyly is varied. Several different hypotheses have been offered as to the cause of this condition. Camptodactyly can be divided into three different types (Table 701.3 ).

Table 701.3

Adapted from Kozin SH: Pediatric hand surgery. In Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, editors: Review of hand surgery, Philadelphia, 2004, WB Saunders, pp 223–245.

Treatment

Mild contractures of <30 degrees are usually well tolerated and do not need treatment. Serial casting and static and dynamic splinting are the treatments of choice for preventing progression of contractures. This should be performed until the child is skeletally mature.

Surgical treatment is limited to the treatment of severe contractures. At the time of surgery, all contracted and anomalous structures are released. Results of contracture release for camptodactyly are mixed; often a loss of flexion results from an attempt to improve extension.

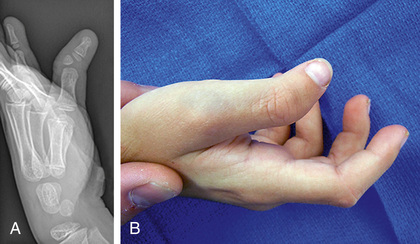

Clinodactyly

Angular deformity of the digit in the coronal plane, distal to the metacarpophalangeal joint, is clinodactyly. The most commonly observed finding is a mild radial deviation of the small finger at the level of the distal interphalangeal joint. This is often due to a triangular or trapezoidal middle phalanx. In some cases, a disruption of the physis at the middle phalanx produces a longitudinal epiphysial bracket. This bracket is thought to be the underlying cause for the formation the “delta phalanx” that is often observed in clinodactyly. Clinodactyly has been observed in other fingers, including the thumb (Fig. 701.7 ) and ring finger.

Treatment

Often the treatment for clinodactyly is observation and not surgery. For severe deformities and for those affecting the thumb, surgery may be indicated. Surgery is technically demanding. Bracket resections, corrective osteotomies, and growth plate ablations are the most common procedures performed to correct the observed angular deformities. Results are good and recurrences are uncommon when an appropriate procedure is performed.

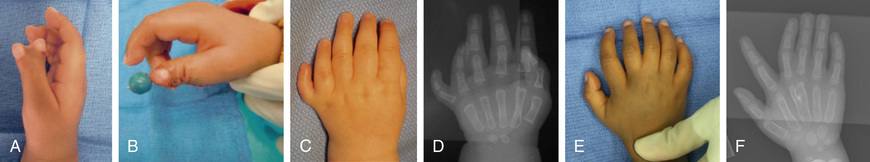

Polydactyly

Polydactyly or duplication of a digit can occur either as a preaxial deformity (involving the thumb) or as a post axial deformity (involving the small finger) (Table 701.4 ). Each has an inherited and genetic component. Duplication of the thumb occurs more in whites and Asians and is often unilateral, whereas duplication of the small finger occurs more frequently in African-Americans and may be bilateral. Transmission is typically in an autosomal dominant pattern and has been linked to defects in genes localized to chromosome 2.

Duplication of the thumb was extensively studied by Wassel. Wassel subdivided thumb duplication based on the degree of duplication. The seven types according to Wassel are listed in Table 701.5 . Small finger duplication has been further subdivided into two types. Type A is a well-formed digit. Type B is a small, often underdeveloped supernumerary digit.

Table 701.5

Treatment

Thumb and small finger duplication is typically treated with ablation of the supernumerary digit. Treatment options vary based on the degree of involvement. Less well-formed digits can be treated with suture ligation. Well-formed digits require reconstructive procedures that preserve important structures such as the collateral ligaments and nail folds (Fig. 701.8 ).

Thumb Hypoplasia

Hypoplasia of the thumb is a challenging condition for both the patient and the doctor. The thumb represents about 40% of hand function. A less-than-optimal thumb can severely limit a patient's function as he or she grows and develops. Hypoplasia of the thumb can range from being mild with slight shortening and underdeveloped musculature to complete absence of the thumb. Radiographs are useful to help determine osseous abnormalities. The most important finding on physical exam is the presence or absence of a stable carpometacarpal (CMC) joint. This finding helps to guide surgical treatment.

Treatment

If the thumb has a stable CMC joint, reconstruction is advised. Key elements of thumb reconstruction include rebuilding the ulnar collateral ligament of the metacarpophalangeal joint, tendon transfers to aid thumb abduction, and procedures to deepen the web space.

If a stable CMC joint is not present or the thumb is completely absent (Fig. 701.9 ), pollicization (surgical construction of a thumb from a finger) is the definitive treatment. Pollicization is a complex procedure rotating the index finger along its neurovascular pedicle to form a thumb. This procedure is typically performed at around 1 yr of age and may be followed by subsequent procedures to deepen the web space or augment abduction (Fig. 701.10 ).

Syndactyly

Failure of the individual digits to separate during development produces syndactyly. Syndactyly is one of the more common anomalies observed in the upper limb (Table 701.6 ). It is seen in 0.5 of 1,000 live births. Syndactyly can be classified as simple (skin attachments only), complicated (bone and tendon attachments), complete (fusion to the tips, including the nail), or incomplete (simple webbing).

Treatment

Division of the conjoined digits should be considered before the 2nd yr of life. Border digits should be divided earlier (3-6 mo) because of concern for tethered growth of digits of unequal length. Digits of similar size, such as the ring and middle, may wait until the child is older to consider separation. Reconstruction of the web space and nail folds, as well as appropriate skin-grafting techniques, must be used to ensure the best possible functional and cosmetic result (Fig. 701.11 ).

Fingertip Injuries

Young children are fascinated with door-jambs or car doors and other tight spaces, making crush injuries to the fingertips quite common. Injury can range from a simple subungual hematoma to complete amputation of part or the entire fingertip. Radiographs are important to rule out fractures. Physeal fractures associated with nailbed injuries are open fractures with a higher risk of osteomyelitis, growth arrest, and deformity if not treated promptly with formal surgical debridement and reduction. Tuft fractures involving the very distal portion of the distal phalanx are common and require little specific treatment other than that for the soft tissue injury.

The treatment of the soft tissue injury depends on the type of injury. For suture repairs, only absorbable sutures should be used, because suture removal from a young child's fingertip can require sedation or general anesthesia. If a subungual hematoma exists but the nail is normal and no displaced fracture exists, the nail need not be removed for nailbed repair. If the nail is torn or avulsed, the nail should be removed, the nail bed and skin should be repaired with absorbable sutures, and the nail (or a piece of foil if the nail is absent) should be replaced under the eponychial fold to prevent scar adhesion of the eponychial fold to the nail bed that can prevent nail regrowth.

If the fingertip is completely amputated, treatment depends on the level of amputation and the age of the child. Distal amputations of skin and fat in children <2 yr of age can be replaced as a composite graft with a reasonable chance of surviving. Similar amputations in older children can heal without replacing the skin as long as no bone is exposed and the amputated area is small. A variety of coverage procedures exist for amputations through the midportion of the nail. Amputations at or proximal to the proximal edge of the fingernail should be referred emergently to a replant center for consideration for microvascular replantation. When referring, all amputated parts should be saved, wrapped in saline-soaked gauze, placed in a watertight bag, and then placed in ice water. Ice should never directly contact the part, because it can cause severe osmotic and thermal injury.

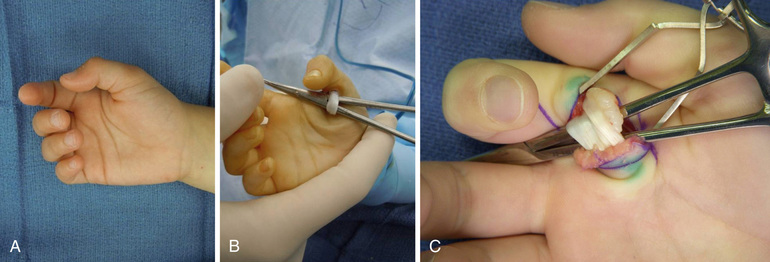

Trigger Thumb and Fingers

The flexor tendons for the thumb and fingers pass through fibrous tunnels made up of a series of pulleys on the volar surface of the digits. These tunnels, for reasons that are not well understood, can become tight at the most proximal or 1st annular pulley. Swelling of the underlying tendon occurs, and the tendon no longer glides under the pulley. In children, the most common digit involved is the thumb. It has classically been thought to be a congenital problem, but prospective screening studies of large numbers of neonates have failed to find a single case in a newborn child. The incidence of trigger thumb is approximately 3 per 1,000 children at 1 yr of age. Trauma is rarely a feature of the history, and the condition is often painless. Overall function is rarely impaired. A trigger thumb typically manifests with the inability to fully extend the thumb interphalangeal joint. A palpable nodule can be felt in the flexor pollicis longus tendon at the base of the thumb metacarpal phalangeal joint volarly. Other conditions can mimic trigger thumb, including the thumb-in-palm deformity of cerebral palsy. Similar findings in the fingers (index through small) are much less common and may be associated with inflammatory conditions such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 701.12 ).

Treatment

Trigger thumbs spontaneously resolve in up to 30% of children in whom they are diagnosed before 1 yr of age. Spontaneous resolution beyond that age is not common. Corticosteroid injections are effective in adults but are not effective in children and risk injury to the nearby digital nerves. Surgical release of the 1st annular pulley is curative and is generally performed between 1 and 3 yr of age. Treatment of trigger fingers other than the thumb in children involves evaluation and treatment of any underlying inflammatory process and in some cases surgical decompression of the flexor sheath and possible flexor tendon partial excision.