General under Liu Bang, Emperor

of the Western Han Dynasty

Generals are easy to get, but when it comes to a man like Han Xin, there is not his equal among the officers in the country. If you really want to contend for the empire, except for Han Xin there is no one who can plan it for you.

—Xiao He, chief advisor to Emperor Liu Bang

VERY LITTLE IS KNOWN of Han Xin’s early years other than that he was of common birth and lived in poverty in his late adolescence and early adulthood. The primary source for Han Xin’s life and career is the Shihchi of Sima Qian, known in the West as Records of the Grand Historian. Sima Qian tells stories of Han Xin begging for food just to survive. In another, Han Xin apparently was acting tough and was challenged by a “butcher” (probably another term for bully). “You are tall and big and like to carry a sword.… If you can face death, try to stab me. If you cannot face death, crawl between my legs,” the bully is supposed to have said. “Then Han Hsin, after looking him over carefully, bent down and crawled between his legs on his hands and knees.”1

This humbling experience had a great effect on him and later in life, after he had achieved success, he rewarded the bully as well as those who had fed him.

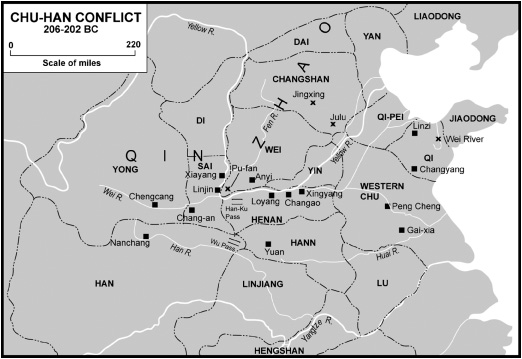

Han Xin joined the army of Xiang Liang, founder of the Western Chu Kingdom, in March 208 BC, early in the dynastic rebellions against the Qin Dynasty. After Xiang Liang was defeated and killed, Han Xin shifted his allegiance to Liang’s nephew and successor, Xiang Yu. Here he took his first very small step toward greatness when he was named a “palace gentleman,” which was probably just a palace door guard. He must have had regular access to Xiang Yu, however, for he suggested several strategies to his master, all of which were rejected. In March or April 206 BC, the war against Qin was over and as Xiang Yu was the dominant general, he began assigning kingdoms to his generals. Liu Bang, one of his most successful generals, was given the province of Han, roughly corresponding to modern southern Henan and northern Hubei. At this point Han Xin left Xiang Yu’s army for Liu Bang’s, hoping a new commander might be more appreciative of his talents. One can only ponder on how these talents were acquired; it is known that Han Xin had studied the writings of Sun Tzu, but that was hardly unusual for military men of that day.

Soon thereafter, Han Xin violated some law and, with a number of others, was sentenced to death. When his turn came before the executioner, he noticed Liu Bang’s chief advisor, Xiao He, and called out to him, “Does not the emperor [Liu Bang] want to go after the empire? Why should he have a valiant fighter beheaded?”2 Intrigued, Xiao He freed Han Xin and talked with him at length. During these discussions it became clear to him that Han Xin indeed had a brilliant military mind. Xiao He mentioned his discovery to Liu Bang, who in turn appointed Han Xin head of the commissariat, something along the lines of quartermaster general. Further discussions convinced Xiao He of Han Xin’s talents, but Liu Bang was uninterested.

That changed a couple of months later when a number of Liu Bang’s generals deserted him. Han Xin, thinking that commissary general was as high as he would rise and not believing it to be a position in which he could employ his talents, deserted as well. Hearing of this, Xiao He pursued him. It was reported to Liu Bang that Xiao He had deserted as well. Liu was greatly pained at the loss of his chief lieutenant and was even more greatly surprised when Xiao He returned to court a few days later. Xiao He explained that he had chased down Han Xin and convinced him to return to the emperor’s service. This finally convinced Liu Bang that Han Xin was a man to be trusted and taken seriously, and on Xiao He’s advice he promoted him to general-in-chief.3 It was now June 206 BC.

THE TERRA COTTA WARRIORS OF XIAN, protecting the grave of Emperor Qin Shihuangdi, are perfect examples of how a warrior would have been accoutered in the time of the Chu-Han Conflict. The primary military arm was the infantry, which by the end of the third century BC would have been wearing scale armor made of iron, bronze, or leather strips sewn together with leather thongs. The terra cotta soldiers almost certainly represent an elite imperial guard force, but even the regular soldiers probably had at least leather armor.

The standard weapons were the halberd and the bow. The ge, a dagger-axe in use for almost a thousand years, vaguely resembles the European halberd or poleax. It had a point extending at right angles to the shaft, which would be used by swinging the weapon. It was originally made of bronze or jade, but by the end of the third century iron weapons were becoming somewhat more common. Some have suggested that the dagger blade could be used against charioteers, which may be one reason why chariots had become used mainly for officer transport or ceremonial purposes by the end of the third century. The head of the dagger grew wider and heavier by the same time period. The ji, another common weapon, was much like the ge but with a spear point extending from the shaft. Both were about ten feet long. Spears ranging from five to twelve feet were used as thrusting weapons.

The infantry was also well manned with archers. A standard five-man squad would usually be made up of three spearmen and two archers, who used both the longbow, made of bamboo, and the crossbow, which had been invented in the sixth century BC and first been used in a pitched battle (as opposed to a siege) in 341 BC. Crossbows reportedly had a range of six hundred paces—roughly the same as six hundred yards. By the time of the Chu-Han conflict, they might have become light enough (and easily enough drawn) to be used by cavalry, but those most likely came a few decades later.

Cavalry was also an important military component by this time. In previous eras the Chinese had shunned the use of horses as too barbarian. Experience fighting against the Hu on the northwestern frontier began to change some attitudes by the late fourth century, however. Wu Ling of Chao created a cavalry force and obliged his men not only to learn to fight like the barbarians but to dress like them as well. At first only peasants and Hu mercenaries were cavalrymen, but by the time of the Qin dynasty all social classes were involved. Cavalry was used mainly for harassment and pursuit rather than shock. The primary weapon for the cavalry was the bow, but horsemen also carried swords, which most infantrymen carried as well—the jian, a straight, double-edged blade roughly three feet long.4

DURING THE CLOSING STAGES OF THE REBELLION against the Qin, Xiang Liang invited Liu Bang to aid him in selecting a new king of Chu. The only descendent they could find, a grandson of King Huaiwang, was a shepherd, but he was named the new king of Chu and given the same name as his grandfather. After Xiang Liang was killed in battle, the shepherd king announced that whoever conquered the Qin capital of Chang’an would be the new king of that principality. Liu Bang and Xiang Yu both asked for the honor. According to contemporary historiographer Sima Qian, the goal was the “region within the passes.”5 This describes the Guanzhong Plain area around Chang’an, which is bordered by the Wei River to the north and mountain passes to the west, south, and east. Although both generals yearned for the glory the conquest would bring, Xiang Yu instead marched northward to the Zhou principality to relieve the prince there from an attack by Qin general Zhang Han, who had killed Xiang Liang.

Liu Bang’s army therefore marched against Qin. He captured Luoyang and Nanyang, then marched westward through the Wuguan Pass (modern Danfeng) and up the Dan River to Chang’an. The Qin prime minister tried to bargain with Liu, offering to divide the kingdom with him equally; the offer was rejected. The grandson of the emperor Qin Shihuangdi killed the prime minister and took the throne. He voluntarily surrendered his kingdom to Liu in January 206 BC after serving as emperor a mere forty-six days.

In his campaign in Zhou, Xiang Yu negotiated the surrender of his rival Zhang Han and captured 200,000 soldiers in the process. Although this would have brought his army up to a reported 600,000, Xiang instead decided to kill his prisoners—by burying them alive. (He spared Zhang Han, later naming him king of Yong.) He then marched his army to Chang’an to claim it as his own. Liu Bang met Xiang Yu at the Wuguan Pass and found himself outnumbered four to one. Deciding discretion was the better part of valor, he informed Xiang Yu that he had been holding the capital in trust, awaiting his arrival: “I did not presume to take possession of the tiniest thing I came upon. I registered the officials and people, I sealed up the treasuries, and I waited for the general.… Day and night I was expecting the general to arrive, so how would I go against him!”6 Xiang Yu further illustrated his brutality as he proceeded to occupy Chang’an, kill the Qin emperor and all his family, and burn the palace. He afterward invited Liu Bang to a celebratory dinner during which he planned to assassinate him, but Liu Bang escaped.

With the rebellion now officially over, Xiang named Chu king Huai-hang to be the new emperor, Yidi. He made himself king of Western Chu and named eighteen other generals and advisors to principalities across China. Instead of receiving the valuable and prestigious land of Qin, therefore, Liu Bang received the state of Han, on the southwest rim of “civilized” China. This “reward” seemed to him and most others to be a slap in the face. It was at this time that Liu Bang finally promoted Han Xin, who immediately proposed a strategy for Liu Bang to unseat Xiang Yu and claim the title of emperor for himself. Han Xin argued that Xiang was an able general but a poor leader. His execution of 200,000 Qin soldiers—while sparing their generals—had unnerved Qin’s population, especially since those same generals were now the kings of the three parts of Qin: Yong, Sai, and Di. Further, when Liu had occupied the Guanzhong area he had treated the people leniently and cancelled the Qin emperor’s harsh law code, replacing it with one of only three rules. Thus, Liu had the Qin people’s support and they would welcome him as their king and even as their emperor. All Liu Bang needed was an opportunity. “The conflict between them was more than a question of personalities; it was a battle between old and new, between the aristocrat and the peasant, the former kingdoms and the unified state,” writes Ann Paludan, in her major book on the Chinese emperors.7

Upon withdrawing to his mountain capital in Han, Liu Bang had destroyed the zhan dao, wooden-plank roads (alternately described merely as wooden bridges) along cliffs on the way to Chang’an. This was designed both to protect himself from attack and to assure Xiang Yu that he would not be attacking the capital city. Luckily for Liu Bang, he was not the only unhappy king—the king of Qi was assassinated by one of his generals, and Xiang Yu gathered his forces from their capital in his home territory at Pencheng (modern Xuzhou) to suppress that rebellion.

This was Liu Bang’s chance; with Xiang Yu occupied far to the east, he could now follow up on Han Xin’s plan to unseat Xian Yu and claim for himself the title of emperor. First, Liu placed soldiers to work repairing the zhan dao. This alerted King Zhang Han of Yong, who placed troops in a blocking position for Liu Bang’s outbreak.

Liu Bang and Han Xin, meanwhile, led an army westward through Hanzhong (modern Nancheng), then marched northward to Chencang (modern Baoji) on the Wei River, just upstream from Chang’an. The three kings of Qin were taken by surprise and surrendered to the Han army, and Liu Bang ruled the region—within a “few months,” according to Chinese military historian Sun Haichen.8 Whether that “few months” in the autumn and winter of 206 BC included the preliminary actions before Chencang, a battle against all three kings at once, or defeating the kings in turn is not clear. To this day in China, “advancing by way of Chencang” is an idiom for a secret move or an illicit rendezvous.

Xiang Yu could do nothing about Liu Bang’s conquest, because the conflict in Qi dragged on. Liu thus seized the opportunity to expand territory under his control. He sent a column north to take control of two commanderies, Shang and Beiji, west of the Yellow River. He also sent a column toward Xiang Yu’s capital at Pengcheng, where his wife and his father were being kept hostage. Xiang Yu’s army turned them away. Seeing a potential threat toward his capital, Xiang Yu ordered that Emperor Yi leave the city; continuing his ruthless ways, he quickly thereafter ordered the king of Jiujiang to assassinate the expendable monarch. Liu Bang and Han Xin, in the meantime, captured Luoyang and forced the surrender of the king of Henan in February 205 BC, then took over the principality of Wei, just across the Yellow River, seven months later. This success brought defections from Xiang’s camp into Liu Bang’s, including the king of Hann. The king of Yin, Sima Mao, resisted but was defeated; he fled to Chaoge, which Han Xin soon besieged. A feigned withdrawal drew Sima Mao out of the city and he was ambushed and captured. His submission to Liu Bang followed.

Now in possession of the city of Luoyang, Liu Bang was succeeding in Han Xin’s measured strategy to strangle Xiang Yu’s home province of Chu. Two things changed his mind against this course of action, however. A deserter from Xiang Yu, Chen Ping, advised Liu to march on Pengcheng, Xiang’s capital city, now relatively undefended since Xiang was fighting in Chi. Liu also met Dong-gong, a longtime member of the ruling clique in Luoyang, who suggested that Liu Bang rally the kings around Emperor Yi’s assassination. This brought in pledges of loyalty from the kings of Wei and Dai. Now with an army reportedly of a half-million9 soldiers from his own kingdom as well as Sai, Di, Hann, Wei, Yin, Dai, and Henan, Liu Bang marched for and captured Pengcheng in the spring of 205 BC. Unfortunately, he did nothing to secure his victory: “Drunk with victory and puffed with pride, Liu Bang seized the treasures and women in Xiang Yu’s palace for himself and indulged in drinking parties and various other dissipations every day.”10 He was thus surprised when Xiang Yu returned with a mere 30,000 men, catching the Han army unaware and defeating them so badly that “more than 100,000 of the Han troops all went into the Sui River, which ceased to flow because of this.”11 Liu Bang managed to withdraw to Xingyang on the Yellow River.

HAN XIN GATHERED AN ARMY AND MARCHED to his emperor’s rescue, driving back Chu forces sufficiently for the Han army to dig in at Xingyang. In the face of this turn of fortune, all of Han’s recent allies hastened to swear loyalty to Xiang Yu. In Xingyang, the king of Wei asked permission to travel home to take care of his ailing parents. Once there, he courted Chu support. Liu Bang sent an ambassador on a futile mission to negotiate. Then, feeling himself strong enough in Xingyang, he detached Han Xin with an army of unknown size to recover Wei.

Bao, the king of Wei, prepared for such an eventuality. He fortified the Yellow River crossing at Pu-fan and stationed a force at Linjin (Lin-chin) to block a river crossing. When Han Xin arrived in the autumn of 205 BC, he proceeded to follow Sun Tzu’s cardinal rule: all warfare is based on deception. Han Xin gave the impression of establishing a large camp by displaying many banners and gathering a large number of boats to launch an amphibious assault. As this was happening, he secretly led the bulk of his army several miles northward to the town of Xiayang. There, they constructed a fleet of pontoon crafts (reportedly made of wooden planks lashed to earthenware jugs)12 and crossed the river. With the Wei forces still facing the diversionary force at Linjin, Han Xin marched his forces far to the east and attacked the Wei capital city at Anyi (Yuncheng). Learning of this flanking movement, King Bao marched his army away from the river back to Anyi. He was defeated outside the city and captured, after which he once again swore allegiance to Liu Bang. At this point, Han Xin’s plan was to march north to Dai, then east through Zhao, which would put him in a position to strike Xiang Yu’s army from the rear.

Han Xin proceeded northeast to confront the king of Dai; along the way Liu Bang sent him some reinforcements under Zhang Er. When he was dividing up the realm in 206 BC, Xiang Yu had named Zhang Er king of Changshan inside the kingdom of Zhao, alongside Chen Yu. Chen Yu, jealous of his supporting role, overthrew Zhang Er and reinstated the previous king of Zhao. In gratitude, the king named Chen Yu king of Dai. Chen Yu appointed a subordinate, Xia Yue, to act as regent while he stayed in Zhao. Thus, Zhang Er proved to be a valuable asset to Han Xin, for Zhang had both a knowledge of their opponents and a desire for vengeance. In the autumn of 205 BC, Han Xin and Zhang Er defeated Dai forces at Yanyu and captured Regent Xia Yue. Meanwhile, Xiang Yu had been exerting pressure against the Han position at Xingyang, so Liu Bang ordered most of Han Xin’s best troops to reinforce his position, leaving Han Xin and Zhang Er with some 30,000 less-experienced soldiers. Still, they continued their march to confront the next enemy, the forces of Zhao.

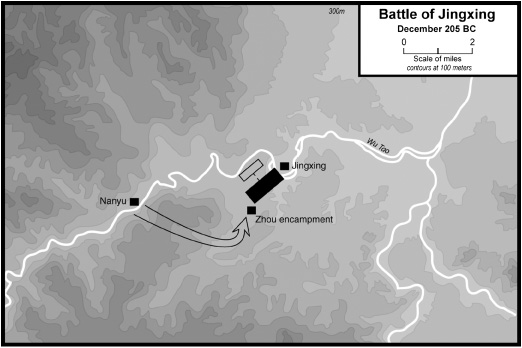

Han Xin’s troops marched through mountain passes until they reached Jingxing (the Jing gorge) sometime late in 205 BC. They entered this extremely narrow pass heading eastward; at the far end waited 200,000 Zhao troops in a fortified encampment. They were under the command of Chen Yu, the lord of Cheng’an, whose second-in-command was Li Zuoche, lord of Guangwu. Li Zuoche advised Chen Yu to send him with 30,000 men around to cut off the lines of communication, bottle the Han forces up in the pass, and starve them out. Meeting them on open ground would not be wise: “An army such as his, riding the crest of victory and fighting far from home, cannot be opposed.” If contained in the gorge, however, the Han army would be unable to live off the land and too far from a supply base to last very long; “before ten days are out I will bring the heads of their two commanders and lay them beneath your banners!” Li Zuoche promised his general. “I beg you to give heed to my plan, for, if you do not, you will most certainly find yourself their prisoner.”13

Chen Yu, a strict Confucianist, disagreed. To send forces around Han Xin’s rear would not be something an honest follower of Confucius would do. Besides, he thought the number of Han troops was closer to 3,000 or 4,000 rather than the reported 20,000 to 30,000; if he did not directly confront a force he greatly outnumbered, none of his subordinates would respect him: “The other nobles would call me coward and think nothing of coming to attack me!”14

Han Xin sent spies ahead to learn what the Zhao forces intended, and they discovered Li’s advice and Chen’s rejection of it. This, coupled with advice from Zhang Er concerning Chen Yu’s nature, motivated Han Xin to proceed. Having taken the measure of his opponent, Han Xin continued his march into the gorge. Some ten miles from the mouth, he encamped. That evening he sent 2,000 light cavalry, each man carrying a red Han banner, into the mountains to circle around behind the Zhao camp. Their orders were to stay hidden in the hills until they saw the Zhao camp abandoned. He also sent out a 10,000-man vanguard to deploy opposite the Zhao camp with orders to dig in with their backs to the river. This foolish deployment sent the Zhao army into peals of laughter.

At dawn the next morning, having given his men a light meal, Han Xin confided to his subordinates that they would be dining in the Zhao fort that night. None believed him, but they followed his orders nonetheless. Han Xin led the remainder of his army to the front of his vanguard, deploying with his banners and drums, the signs of his command. At that, Chen Yu sent his first wave into battle. Han Xin’s men fought hard but gradually withdrew into the main body, abandoning their banners and drums. As Han Xin had foreseen, that brought the rest of the Zhao army out of their camp, eager to take part in the rout. Still, the Han forces fought so desperately they could not be destroyed. As the battle raged, the light cavalry force, hidden in the hills, emerged and entered the Zhao fort, killing the few remaining defenders. They then proceeded to take down all Zhao flags and replace them with Han banners. In the face of Han Xin’s desperate fighting, Chen Yu ordered his men to withdraw and regroup for another attack. His men, now seeing the Han banners in their own camp, became panic stricken. They assumed their commanders were now dead or captured, so their morale collapsed and they began to flee. Although their commanders beheaded a few to halt the retreat, this act was fruitless.15 As the Zhao army began to break, Han Xin ordered the attack, routing the enemy and killing Chen Yu. Chen’s advisor Li Zuoche was taken captive and brought before Han Xin, who ordered him unbound and treated with utmost respect. He proceeded to question Li on the best strategy to pursue, now that Chen Yu was dead and the king of Zhao was in captivity.

That evening, as they were dining in the Zhao camp as he had predicted, Han Xin’s subordinates questioned his tactics. After all, they pointed out to him, Sun Tzu’s directives called for a river to be on the flank or in front, not to the rear. Han Xin replied, “Does not the book say, ‘Put them at a fatal position and they will survive?’ Besides, I did not have the chance to get acquainted with the troops at my disposal.… Therefore, I was compelled to plunge them into a desperate position where everyone would have to fight for his own life. If I had provided them with a route of escape, they would all have run away.”16

Han Xin’s movement to contact was an approach march, since his spies had given him exact details of the Zhao position. He had launched a deliberate attack that had some of the aspects of a feint. The main difference was that the bulk of his force was the feint and his small light cavalry force proved to be the decisive attack; at the same time, the use of flags in the Zhao fort to give the impression of a larger force was a feint in itself, followed by a counterattack from the main body. The key to the entire battle was audacity. Few battles in history better define the word: Han Xin risked more than 20,000 men in a position with no retreat in order to lure a massively larger force out of its position and then depended on a deception in the enemy rear to break their morale.

LIU BANG AND XIANG YU HAD SPENT months in 204 BC facing each other in the area east of Luoyang, between the Yellow River and the upper reaches of the Huai River, blocking each other’s path toward the other’s territory.17 Cities were won and lost, with Xingyang and Changgao as the two major points of contention. Liu Bang was able to leave the combat area periodically to recruit forces in the area around Chang’an. In the summer of 204 BC, one of his advisors suggested that he not return directly to the battlefields but march south and recruit even more forces with the aid of Qing Bu, king of Linjiang, and then station their forces in the city of Yuan. This activity drew Xiang Yu southward, away from the Luoyang region, in hopes of catching Liu Bang in the open, but the Han king and his new army stayed within Yuan’s walls. Peng Yue, king of Liang, meanwhile harried Chu forces in the east. When Xiang Yu turned to chastise Peng Yue, Liu Bang led his army to reinforce Changgao. Once done driving off Peng Yue, Xiang Yu returned to confront Liu Bang and quickly captured both Xingyang and Changgao, but not before Liu Bang made a hasty escape. This was sometime in the early autumn of 204 BC. He fled north across the Yellow River to Xiuwu, where Han Xin and Zhang Er were camped.

Liu Bang awarded Zhang Er military command over Zhao and sent Han Xin to attack eastward into Qi. He meanwhile fortified his position at Xiuwu and sent some cavalry to reinforce Peng Yue, who was once again harassing Chu supply lines. As Han Xin was marching toward the Pingyuan Ford across the Yellow River into Qi, Liu Bang sent an ambassador, Li Yiji, to negotiate an accord with Tian Guang, king of Qi. He succeeded in this mission: “As a result, Tian Guang revolted against Chu and joined in alliance with Han, agreeing to participate in an attack on Xiang Yu.”18 While on the march Han Xin learned of this new alliance, but continued onward. After all, he had not received royal orders to stop the invasion. Trusting to his new alliance, Tian Guang dispersed his armies and continued to entertain Li Yiji. Han Xin therefore had no trouble capturing Lixia and marching on the Qi capital of Linxi. Before making his escape, Tian Guang boiled Li Yiji alive for supposedly deceiving him. Tian Guang fled and sent a request for aid to Xiang Yu, who “accordingly sent Long Ju to go and smite him [Han Xin].”19 Long Ju’s army of 200,000, together with those rallied by Tian Guang, marched to intercept Han Xin’s army. The two forces met each other on opposite sides of the Wei River, probably at the end of 204 BC.

Once again, Han Xin’s opponent underestimated him. One of Long Ju’s subordinates advised him to dig in and postpone battle; once the people of Qi learned that their king was still alive they would rally around him and the Han army would be isolated in hostile territory. Long Ju scoffed at the notion of avoiding a fight: “I have always felt Han Hsin to be inconsequential. He relied on a washer woman for food, so he never had any plans to support himself; he was insulted by having to crawl between a man’s legs, so he lacks the courage to confront people. He is not worth worrying about.”20

When night fell, Han Xin sent a number of his men upriver with orders to fill 10,000 sandbags and dam the river. This done, the river fell considerably but continued to run. The next morning Han Xin led his 70,000 soldiers across the river to assault Long Ju’s army. After some indecisive combat, Han Xin withdrew his army back across the river. Long Ju, “truly elated, exclaimed: ‘I knew Han Hsin was a coward!’ Thereupon he ordered his army to ford the river and pursue Han Hsin’s forces.”21 Seeing this, Han Xin gave the signal for the sandbag dam to be opened, and the rush of water drowned a large portion of the Chu troops. Long Ju was left with only a handful of men across the river, pinned against it by the now superior Han force. As the remainder of his army watched from across the river, Long Ju was killed. Tian Guang of Qi fled and was finally chased to ground and captured at Che’ng-yang. Han Xin proceeded to pacify the remainder of Qi.

While Han Xin did engage in an approach march for his movement to contact, it is unclear whether he chose the battleground. Many of the details around the battle are unrecorded. He engaged in a deliberate attack, followed by a deceptive withdrawal, using his knowledge of Long Ju’s prejudice. Although Long Ju should have noticed and investigated the radical difference in river level, Han Xin’s interruption of the flow was a complete surprise. With his entire force on his own side of the river and Long Ju’s force now both weakened and divided, Han Xin was easily able to concentrate his army for the purpose of Long Ju’s destruction. The exploitation of the trapped army was complete, although the remainder across the river fled without pursuit. Only Tian Guang was chased; with him captured rather than killed another Qi uprising was probably averted.

Over the next several months Han Xin was named king of Qi and spent his time consolidating the province. Liu Bang seemed to be growing wary of Han Xin’s potential political ambitions, but Han Xin proved his loyalty by rejecting an offer from one of Xiang Yu’s emissaries. One of his own advisors, seeing how powerful and talented Han Xin was, advised him to support neither Han nor Chu, but to establish himself as a third power and propose a three-way rule; thus, no one power would be able to overcome the other two: “if you choose to follow Chu, the men of Chu would never trust you, and should you choose to follow Han, the men of Han would quake with fear. With gifts such as these, whom should you follow?”22 Even after extended arguments along these lines, Han Xin refused to abandon his fealty to Liu Bang.

Meanwhile, Xiang Yu alternated between fighting Liu Bang’s forces near the Yellow River and securing his lines of communication from Peng Yue’s harassment. He finally proposed to Liu Bang that they split China between them, an offer he had rejected when Liu Bang suggested it after his defeat at Pengcheng. Liu Bang accepted the offer, but as Xiang Yu was withdrawing back to Chu, the Han forces followed. Liu Bang called all his generals to meet him at Guling, but Han Xin and Peng Yue did not arrive. Thus, Liu Bang was forced to retreat once again to his defenses. After promises of increased land rewards for his generals (including Han Xin), Liu Bang’s generals gathered together for a final battle against the Chu forces at Gaixia (modern Beng-bu). This time the Han forces were overwhelming: Han Xin commanded 300,000 in the center, with forces on each flank and two more in reserve. Xiang Yu’s army numbered but 100,000. “Han Xin advanced and joined in combat but, failing to gain the advantage, retired and allowed General Kong and General Bi to close in from the sides,” Sima Qian relates. “When the Chu forces began to falter, Han Xin took advantage of their weakness to inflict a great defeat.”23

A handful of troops apparently remained under Xiang Yu’s command after the battle, but were soon surrounded by Han Xin’s force. Han Xin had his men sing local Chu folk songs, “so King Xiang said in great astonishment: ‘Has Han already got the whole of Chu? How many men of Chu there are!”24 Thus was Xiang Yu deceived into believing the worst about his position. He fled with a handful of cavalry and made a last stand against pursuing Han cavalry, inflicting considerable casualties, before fleeing alone. Given an opportunity to escape across the River Wu, he chose instead to face his pursuers one last time, reportedly killing several hundred Han soldiers and receiving ten wounds himself. He then committed suicide.25

BEING OUTNUMBERED IN EVERY BATTLE EXCEPT GAIXIA, Han Xin had to be a master of the principle of economy of force first and foremost. At the outflanking movement against the king of Wei, he depended on a small force appearing to be a much larger one preparing to cross the Yellow River at Linjin. Using a holding force outnumbered ten to one at the Jingxing pass allowed his strike force of 2,000 cavalry to initiate the deception in the enemy fortifications, breaking the enemy’s will. Both of these operations employed sufficient manpower to hold the enemy in place while a flanking force delivered the main blow, whether physically against the king of Wei’s army or psychologically at Jingxing.

For Han Xin, the two principles of maneuver and surprise were effectively inseparable. Sun Tzu’s dictum concerning deception dominated all his tactics. Though the sources mention the siege of Chaoge only in passing, they describe the victory as based on the tactic of the feigned retreat. The Yellow River crossing into Wei was a classic example of “hold ’em by the nose and kick ’em in the pants” in which Han Xin used his smaller wing to pin down a superior enemy, then crossed with his larger wing upriver and swung around the enemy rear.

At Jingxing and the Wei River, Han Xin also demonstrated a characteristic that marks the truly great tacticians: knowing when to break the rules. If one can depend on his opponent to know the same rules, one can predict his actions and take advantage. After Jingxing, Han Xin’s generals questioned his decision to place his men with a river at their back. Sun Tzu advises not to “array your forces near the river to confront the invader but look for tenable ground and occupy the heights.”26 The Zhao soldiers all knew that dictum, hence their breaking out in laughter as Han Xin’s forces deployed. His response: Sun Tzu also says to put men in an untenable position and they will fight like cornered animals since there is no escape.

At the Wei River Han Xin also broke Sun Tzu’s rules about river crossings. “After crossing rivers you must distance yourself from them. If the enemy is fording a river to advance, do not confront them in the water. When half their forces have crossed, it will be advantageous to strike them.… Do not confront the current’s flow.”27 By blocking the river with sandbags, Han Xin did more than “confront” the current’s flow. He employed the feigned retreat tactic again, and followed the dictum of striking when half the enemy had crossed the river. In all his battles, Han Xin engaged in at least one maneuver that his enemy never suspected. Only at Gaixia did the battle seem to be a fairly straightforward affair: attack with the center, withdraw, strike with the flank units. Whether he accomplished a double envelopment is not recorded, but that is the maneuver to do so.

The key to Han Xin’s victories, however, lay in his manipulation of the principle of morale. Unlike Alexander, Han Xin depended not so much on maintaining his own army’s morale as in breaking that of the enemy. Because Han Xin seems rarely to have been in command of men who stayed with him for a long period, he could depend only on his reputation to retain his troops’ loyalty and keep their morale up. That didn’t always work, as shown before the battle at Jingxing when he promised his men they would dine in the Zhao encampment that night. “None of his generals believed that the plan would work,” Sima Qian writes, “but they feigned agreement and answered, ‘Very well.’”28 When Han Xin’s light cavalry force struck from behind and planted Han flags throughout the Zhao camp, however, the vastly more numerous Zhao army lost heart and fled.

Both in Jinxing and at the Wei River, Han Xin also played on the mind of his opposing commander. Aware that neither Chen Yu nor Long Ju took him seriously, Han Xin opened his battles with what seemed to be a foolish move in order to confirm his enemies’ opinions of him in their own minds. This made his deceptions all the more effective, for both opponents overcommitted their forces. When disaster struck, the soldiers of both the Zhao and Chu armies panicked, allowing the smaller Han force to turn their defeat into a rout.

AFTER GAIXIA, LIU BANG became the recognized ruler of China and established the Han Dynasty. He was later given the title Gaotzu, or “Supreme Ancestor.” Liu Bang ruled from the end of February 202 BC through the beginning of June 195 BC. In that time span he did have some trouble with the frontier barbarians, but Han Xin did not fight them. Liu Bang’s opinion of Han Xin’s trustworthiness waxed and waned, alternately leading Liu Bang to deprive him of his army and name him to a high-ranking position, Marquis of Huai-yin. Liu Bang’s primary wife, Empress Lu, did not trust Han Xin and gathered evidence that he plotted rebellion. Invited to the imperial court, he was taken prisoner and executed. In Chinese history, only Cao Cao of the later Han Dynasty is considered near Han Xin’s equal.