Roman General

The art of generalship does not age, and it is because Scipio’s battles are richer in stratagems and ruses—many still feasible today—than those of any other commander in history that they are an unfailing object-lesson to soldiers.

—B. H. Liddell Hart

AS WITH HANNIBAL, details of Scipio’s early years are extremely sketchy. He was born into Rome’s upper crust, descended on both his father’s and mother’s side from the Cornellii, a family from whom consuls had been elected for 150 years. Other than that, little can be confirmed. Even Polybius, who wrote at length on Scipio’s military career, glossed over his youth. He was well educated and admired Greek culture, which in his day was not a respectable characteristic, as the Greeks were viewed as a declining and somewhat profligate society; he must, however, have absorbed some of the Greek rationality in thinking, given the innovations he brought to the battlefield.

Also as with Hannibal, the first anecdote of Scipio’s life concerns his relationship with his father, also named Publius Cornelius Scipio. At age seventeen or eighteen, Scipio the younger accompanied his father into northern Italy to confront Hannibal’s invasion in 218 BC. At the Ticinus River, Carthaginian and Roman cavalry units unexpectedly collided. Scipio the elder led the charge, leaving his son in the care of a unit of veteran cavalry. As the battle began to turn against the Romans, Polybius tells of the younger Scipio rushing to his father’s aid when the elder was wounded and surrounded: “[H]e at first endeavoured to urge those with him to go to the rescue, but when they hung back for a time owing to the large numbers of the enemy round them, he is said with reckless daring to have charged the encircling force alone. Upon the rest being now forced to attack, the enemy were terror-struck and broke up, and Publius Scipio, thus unexpectedly delivered, was the first to salute his son in the hearing of all as his preserver.”1 This episode may have proved his bravery but it was likely not his only combat experience. He may have been at the Battle of the Trebia and was almost certainly at Cannae, after which he rallied many of the disheartened officers. He therefore had firsthand knowledge of how Hannibal fought.

There is also some debate on Scipio’s religious views. Livy recounts a story strongly reminiscent of Alexander. Since the age of fourteen Scipio had gone to the temple daily and stayed there in seclusion for some time, “and it generated the belief in the story—perhaps deliberately put out, perhaps spontaneous—that Scipio was a man of divine origin. It also brought back into currency the rumor that earlier circulated about Alexander the Great, a rumor as fatuous as it was presumptuous. It was said that his conception was the result of sexual union with a snake.”2 Livy also quotes Scipio’s prayer to the gods prior to his expedition to Africa. Before the Roman attack on Novo Carthago, on Spain’s southeastern coast, Scipio told his men that he had had a dream assuring the army of Neptune’s aid in the upcoming operation.

Polybius, writing a century earlier, dismisses such notions. “As for all other writers, they represent him as a man favored by fortune, who always owed the most part of his success to the unexpected and to mere chance … whereas what is praiseworthy belongs alone to men of sound judgment and mental ability, whom we should consider to be the most divine and most beloved by the gods.”3 It has also been suggested that the story is false because a Roman temple was not a place for prayer and meditation but for sacrifice. Hence, the regular worship is implausible, though not impossible.4

Thus the same question regarding Alexander arises concerning Scipio: did he believe himself of divine heritage, or at least divine inspiration? Basil Liddell Hart supposes that Scipio, like Alexander, used such beliefs among his men to his own advantage: “Such supernatural claims only appear occasionally in Scipio’s recorded utterances, and he, a supreme artist in handling human nature, would realise the value of reserving them for critical moments.”5 Appian takes Scipio’s acceptance of divinity as a given. After Scipio’s quick victory at Nova Carthago, Appian says, “He himself thought this, and said so both then and throughout the rest of his life, beginning from this moment.”6 Why not be both religious and practical? After all, it is no more or less likely that he combined rational calculation with religious conviction than did Stonewall Jackson.7

Whatever his parentage, it was saving his father at the Ticino River battle that first brought young Scipio fame; it was his father’s death that led him to his destiny. After recovering from his wounds at the Ticino, the elder Scipio joined his brother Gnaeus in Spain to carry on the war against the Carthaginians in their supply base. The brothers enjoyed some success in battle and in gaining allies among the Spanish tribes, but they were both killed in separate battles in 212 BC. The remnants of their army retreated to the north bank of the Ebro, where they regrouped under the leadership of Lucius Marcius. He was soon superseded by C. Claudius Nero, who arrived with reinforcements late in 211. Nero seemed to be regarded as a temporary commander, for the Roman government was soon looking for his successor. They found him in Publius Cornelius Scipio, the younger.

Too young at twenty-four to officially hold a command rank, Scipio had it bestowed on him by public acclamation, which the Senate confirmed. There has been much debate why this occurred. Certainly there were men with more combat experience, but the government might have deemed them too valuable to spare while Hannibal was rampaging through northeast Italy. Possibly, they hoped the Scipio name, which had been so valuable in gaining allies in Spain, would generate loyalty. Scipio certainly had support within the Senate through his family connections. He seemed to have it all: family, political connections, bravery, ambition, and the charisma with which to sway the crowd.8

Perhaps the Senate withheld the names of other candidates, to give the public the impression they were confirming the only man who would actually volunteer for the job. It certainly would have deflected later criticism had Scipio failed in his mission. What seems most likely, however, is that the Senate recalled Nero because of the need for experienced commanders at home. Had the there been a greater number of qualified men, it would probably have sent someone else instead. Scipio was thus the best of the second string.9 No matter the political circumstances involved, Scipio certainly wanted the job in order to avenge the deaths of his father and uncle.

THE ROMAN ARMY FIGHTING IN SPAIN was organized along the same lines as the forces in Italy. The infantry was deployed in three ranks according to age and experience. The front rank, the hastati, consisted of the youngest recruits, usually late teens through twenties. The principes in the center rank were veterans, usually in their thirties. The first two ranks carried shield, short sword, and javelins (pila). The rear rank, the triarii, was made up of the oldest veterans who acted primarily as a reserve and were armed along the lines of Greek hoplites, with long pikes. Light infantry or skirmishers, the velites, used missile weapons such as slings and light spears in a harassing role prior to the battle’s commencement. Cavalry forces remained secondary, but Scipio would begin to integrate them more thoroughly. In Roman legions they numbered 300, but in the more cavalry-oriented allied legions they usually numbered 600. They usually deployed on the flanks and were primarily for scouting, pursuit, and flank security.

Once in command in Spain, Scipio began altering the standard army format. After his capture of Nova Carthago, he began training his men with intensity. He had them make long marches in full armor and pay close attention to keeping their weapons and equipment in good repair. He also trained them in the use of the gladius hispaniensus, the Spanish sword.

Historians have long debated whether this weapon was first introduced by Scipio or had been used by the Roman army (at least partially) since the Gallic Wars in the 220s BC. In his biography of Scipio, H. H. Scullard argues that a lost passage from Polybius indicates that the Romans had adopted this “excellent Celtiperian sword,” which was “well-pointed and suitable for cutting with either edge” at the time of the Hannibalic War.10 The original Roman gladius was almost exclusively a stabbing weapon—used in thrusting—whereas the Spanish sword could also be used for slashing, making it much more functional in hand-to-hand combat. Probably a sword based on the Spanish style was in use by some Romans, but the high-quality iron and forging techniques were exclusively Spanish. Not until Scipio’s time (primarily after the capture of Novo Carthago) would these have been widely available.

Once the velites were expended, combat did not immediately go hand-to-hand. Each legionary carried two pila, in most cases thrown during the assault before the clash of shields. The Roman throwing spear, the pilum, was a long pointed rod of iron implanted in a wooden shaft. The base of the rod was untempered, and, as noted in the previous chapter, it would bend on impact, making it useless to the enemy. The Romans, however, would reuse enemy javelins. Some have suggested that Roman battles actually involved more long-range fighting, but given that each regular soldier carried but two pila this is hard to accept.11 If the velites were expanded in their numbers, this might seem more plausible.

More innovative than the weapons was Scipio’s rearrangement of the army’s formation. The velites became more important in his army, just as they were about to become throughout the Roman forces. In the wake of the massive losses in the battles against Hannibal, the Roman government was obliged to open the recruiting to greater numbers of the population. Traditionally, the soldiers provided their own weapons and armor and therefore had to be people of some means; the poor were not allowed to join the army. That changed in the years 214–212, when the proletarii became eligible. They were used as velites since they could afford no armor. The government, however, could provide each of them with a small shield and five pila.

In earlier days, the velites were harassing troops—used and then quickly withdrawn as the two armies neared each other. As the numbers of velites grew, so did their role. When Fabius was overseeing the war against Hannibal, skirmishing and harassment were the order of the day, so the use of missile-armed troops became more important. Scipio, by giving velites more training (and therefore discipline), began to grant them a greater role in battle. The Roman army was changing. Allowing the poor to join the army, coupled with wars that grew longer and farther away from Rome, was laying the groundwork for the professional army, very different from the one made up of citizen-soldiers, which had been Rome’s traditional means of defense.12

The Carthaginian army that Scipio went up against in Spain strongly resembled that commanded by Hannibal in Italy, but grew increasingly dependent on Spanish recruits. As we saw with Hannibal, the Carthaginians depended hugely on allied forces as well as mercenaries. The Carthaginian forces were truly multiethnic and multifunctional. They included infantry from northern Africa, Spain, and Gaul, cavalry from Spain or Numidia, slingers from the Balearic Islands, and a leavening of Greek mercenaries.13 The Spanish fielded both heavy and light infantry, based on their shield. The heavy infantry, or scutati, carried the long oval Celtic scutum while the light infantry, the caetrati, carried the caetra, a smaller and lighter buckler. The caetra was wooden, one to two feet across with a central metal boss, and was used for both parrying and attack.

The primary infantry weapons were sword and shield. There were two main sword types. The Iberians used the falcata, with a slightly curving blade that was sharpened hilt to tip on the outer edge, and occasionally on the final third of the blade on the inner curve. This gave it increased parrying ability. Very likely a local adaptation of the Greek kopis or machaera, it was a fearsome weapon. The blade was somewhat wider near the point than at the hilt, moving the center of gravity and increasing the kinetic energy when swung. Diodorus comments that these swords were of such quality that no helmet, shield, or bones could resist their strokes.14 The Celt-Iberians of northern Spain used the straight, double-edged sword that the Romans soon copied. The Spanish smiths creating these were reportedly so good, and the quality of the metal so high, that the blade could be bent almost double then spring back to its original shape. Stabbing spears and javelins rounded out the Carthaginian armory.

WHEN SCIPIO THE ELDER AND HIS BROTHER GNAEUS campaigned in Spain, the Romans had gained two major successes. In 217 they defeated the Carthaginian navy, which hampered any reinforcement from North Africa to Spain. Second, the brothers established strong ties with many of the tribes of the peninsula, although mainly above the Ebro in traditionally Roman-dominated territory. Though one of the tribes turned coat in the middle of two battles in 211—a retreat that led to the brothers’ deaths—and though some tribes drifted toward the Carthaginian cause afterward, most of the alliances they had established continued to lean in Rome’s direction.

In the wake of the defeats in 211, the Roman army retreated north of the Ebro and established a defense. The troops elected Lucius Marcius Septimus as their new commander and sent word of their situation back to Rome. Luckily for them, the three Carthaginian generals fell into immediate squabbling about which was in charge, so Septimus was able to breathe easy. In 211 C. Claudius Nero arrived with reinforcements of 14,000 infantry and 1,100 cavalry and orders to play defense. Nero, as a protege of Fabius, was comfortable with a passive role. With Hannibal still active in Italy, the government viewed Spain as a sideshow—hence, very likely, why Scipio was sent there to begin with. However, when he was elected consul and sent to Spain in 210, Scipio had different ideas.

As for the Punic generals—there were three of them—we know little other than their names. One was Hasdrubal Barca, Hannibal’s brother, who at Scipio’s arrival was in central Spain besieging a town of the Carpetani tribe. Hasdrubal, the son of Gisgo, was on the Atlantic coast at the mouth of the Tagus River in what today would be the central Portuguese coast. The third, the youngest Barca brother, Mago, was among the Conii tribes around the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar). Unlike Hannibal, who went to great lengths to learn about the personalities of his opposing generals, Scipio apparently had little chance to do so with these three, or at least there is no record that he did. From Scipio’s perspective, the important thing was that the three armies were separated too far from each other to provide immediate mutual support. Even more important was the fact that none of these armies was within a ten-day march of his first target, Novo Carthago.

When Scipio arrived in northeastern Spain late in 210 he brought with him an additional 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry. He landed at Emporiae, sent the fleet further down the coast to the main Roman base at Tarraco, and marched along the coastline southward toward Novo Carthago. This gave time for his arrival to be announced through the area, and those tribes that held ties to his father and uncle could (and in many cases did) renew them. Thus, when he reached Tarraco he had not only brought the Roman forces up to about 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry but he also had laid the foundation for supplementing his army even further with local troops.

SCIPIO SPENT THE WINTER OF 210–209 BCE strengthening ties with the local tribes and gathering intelligence on his intended target. Novo Carthago was the primary port of entry for whatever assistance came from Carthage: it held the treasury, it contained a massive armory, and it was where the hostages held to assure the cooperation of the Spanish tribes were kept. Further, it was the primary manufacturing center, especially for weapons. On the surface, Scipio’s attacking the main Carthaginian base seemed rather foolish given his relatively small force. The city was encircled with walls and surrounded by water on three sides—by a harbor and a lagoon. In reality it made perfect sense—as long as it could be captured quickly. Scipio had learned that the garrison numbered a mere 1,000 soldiers. The key was to make sure that the assault did not turn into a long siege, for that would give one or both of the Barcas the chance to march to the city’s relief. Why would the Carthaginians leave their main port and supply base so lightly defended? According to Polybius, it was their rivalry. “Each went his own way in pursuit of personal ambitions, which would hardly have been fulfilled by electing to remain at New Carthage and ensure its security.”15

The key to a successful attack lay in the nature of the lagoon on the city’s northern side. After questioning local fishermen who had navigated it, he learned that in many places the lagoon was not very deep; according to Appian, it was chest high at the water’s crest and knee-high when the water ebbed, which it did every afternoon, when strong north winds blew the waters through the canal and into the harbor. If he could hold the defenders’ attention on a landward assault, a small force would be able to sneak across the lagoon and attack an undefended portion of wall.

He divulged none of his plans to any of his subordinates save one, his longtime friend and co-commander Gaius Laelius. Rumors, on the other hand, ran rampant throughout the army and the population, for which Scipio was grateful; the clot of stories would cloud the single one that was true. In the spring of 209 he led 25,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry down the coast, leaving 3,000 infantry and 500 cavalry to hold his base at Tarraco. According to both Polybius and Livy, Scipio’s army made the march of roughly 300 miles (2,600 Greek stadia) in a week. An army marching 20–25 miles in a day in the nineteenth century was considered to be making good time. Both sources say that the fleet moved along the coast at the same speed. His arrival was certainly a surprise to the citizens and garrison of the city.

The lagoon (which no longer exists) was located on the north side, and the harbor to the south. The peninsula itself was reportedly only 300 yards wide, and Polybius asserts that the circumference of the walls was 22 miles. The city was built on five hills with a sixth outside the city at the base of the peninsula. That was where Scipio established his camp, building defenses on the side not facing the city just in case a relief force should appear and to give his army maneuvering room on the side nearest the city gates. The 1,000 soldiers inside were commanded by Mago (not the same Mago as Hannibal’s brother, who was in another part of Spain), who quickly drafted 2,000 citizens and armed them. When dawn broke and he saw the Romans preparing for an assault and Laelius bringing the Roman ships into the harbor armed with missile-throwing weaponry, Mago assigned his civilians to cover the walls while he placed half his soldiers on a hill near the harbor. The other half he kept in the citadel. As it turns out, the two veteran units were not designated to act as mobile reserves, which would have been the proper assignment, but to be in place for a last stand. This implies that Mago all but conceded the front gates and walls to the Romans.16

Before the attack began, Scipio addressed his troops, reassuring them that there was no relief force readily available, that the garrison was small, that they would be acquiring great wealth at the expense of the enemy, and (best of all) that he had been informed in a dream that the god Neptune had promised assistance. He, of course, knew of the nature of the lagoon’s fluctuating waters, but, according to Livy, “made it out to be a miracle and a case of divine intervention” on behalf of the Romans.17 Polybius uses this as an illustration of Scipio’s genius: “This shrewd combination of accurate calculation with the promise of gold crowns and the assurance of the help of Providence created great enthusiasm among the young soldiers and raised their spirits.”18

Just as the Romans were preparing for their assault, Mago launched a spoiling attack using the civilians, who came pouring out of the city gate. They gave a good account of themselves, but ultimately were both outnumbered and outclassed. When they finally broke and ran back for the city, they were barely able to get the gates closed behind them before the Romans broke through. Scipio quickly sent in 2,000 men with ladders to scale the walls, which, unfortunately for the Romans, were taller than the ladders. Again the civilians proved themselves surprisingly capable by keeping the Romans from reaching the crest; further, overloaded ladders broke and tumbled soldiers to the ground. By midafternoon Scipio called a halt. The defenders were catching their breath and hoping this signaled the beginning of a more traditional siege when the Romans started the assault again. The actions of the first attack were repeated in the second, but neither the Romans nor the defenders showed weakness or hesitation. At this point, defenders from around the walls were called to the landward defenses to aid in that quarter.

That was what Scipio had been waiting for. As the afternoon drew toward evening, his knowledge of the lagoon waters came into play. He led 500 men across the lagoon in the shallow areas and scaled the now-undefended walls on the north side of the city. Once inside they made their way to the gates and hit the defenders from the rear. Roman soldiers were hacking at the gates from the outside when they were opened from within. The civilians broke for their homes, pursued by the Romans who also attacked the 500 soldiers on the harbor-side hill, which had been dodging missile fire and assaults. Butchery of civilians began, stopped only when Mago surrendered the citadel, which he quickly did.

Within a day’s fighting Scipio had seized the major prize of all Iberia. Scipio had made a deliberate attack using all of his forces but the cavalry. The infantry assault at the gates coupled with the pounding from the ships and the assault of marines from that quarter made his march a complete surprise. The frontal assault, pressed hard, was key to the entire action. Had he relied on merely the lagoon crossing he would have been met by stout resistance on the walls, which, according to Polybius, were manned at all points. By launching his main attack at the gates he would probably have broken through sooner or later, but that was what caused the abandoning of the defense from the lagoon side.19

Perhaps just as important as capturing the city and its assets—as well as freeing the hostages the Carthaginians had held—was what Scipio did after the battle was over and the spoils divided. He immediately began training his men in a new style of fighting, along the lines of what he had learned in action against Hannibal. The Roman way of fighting was unimaginative, in his view; Scipio trained the legions to employ tactics more flexible than the traditional Roman frontal attack, which depended entirely on the sheer weight of manpower. He had seen that fail at Cannae.20 To most senior Romans, the traditional way of fighting exhibited the hallowed concept of virtus, virtue, and the belief that deception was dishonest. Perhaps this was a variant on the Greek hoplite attitude, as we saw in the chapter on Alexander: that real men only fought face to face.

The youthful Scipio was willing to break with the old ways. Bitter experience from facing Hannibal had already convinced him that learning from the victors was the key to beating them at their own game. With Novo Carthago he had come into possession not only of a huge arsenal but also the sword makers who specialized in crafting the Spanish sword. With a steady supply of the new weapons he began training his men.

Not many details as to how he did this are available. Nonetheless we do know that he kept the maniples but reorganized them into cohorts. The maniples consisted of two centuries of 80 men each and the cohorts became the next larger unit, containing three maniples, numbering 480 men. Ten cohorts constituted a legion. The result was that the basic tactical unit remained the same, but the cohort was made more flexible, so that it could be moved around the battlefield more easily than the legion. As Goldsworthy observes, “The old lines of the manipular legion were not effective tactical units for independent operations. The cohort, with its own command structure and with men used to working together, may well have fulfilled a need for forces smaller than a legion.”21 Movement on the battlefield—in a direction other than straight ahead—was one of Scipio’s significant contributions to the Roman army’s organization and behavior.

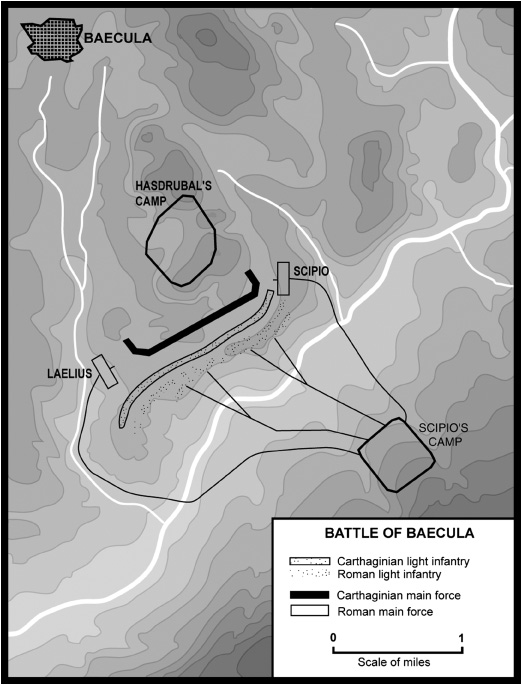

SCIPIO LEFT A GARRISON IN NOVO CARTHAGO and removed the rest of his men north, to their previous base at Tarraco. Inexplicably, none of the three Punic generals did anything to threaten him or try to regain their capital city. They did, however, watch a number of their allies desert and go over to Scipio. By the spring of 208 Scipio was ready to take the field again. The three Punic armies remained divided, and he was determined to fight them before they united. The closest army was that of Hasdrubal Barca, who had spent the winter in Baecula (modern Bailen) near what is today the Guadalquivir River. He was ready for action when he learned of Scipio’s approach, placing himself in a strong position atop a hill with steep sides. The topmost part was fairly flat; there he placed his camp. From there the land sloped down to another shelf where he placed his skirmishers. That shelf was atop yet another, with steep slopes on three sides, so that any assault would involve strenuous climbing. Scipio’s army marched toward the position ready for battle. A good look at the hill brought them up short.

For two days Scipio pondered how to attack. Fearful of the possible arrival of one or both of the other armies, he decided to start the battle. As usual he started with his velites in front, as a skirmish line. Backed with some heavier infantry, they began climbing the hill in front of the Carthaginians, who showered them with javelins and rocks. The Romans nonetheless made steady progress and Scipio sent in some more infantry for support. Hasdrubal at this point decided that the main Roman effort would come at him head-on; that was the way they had always fought. Polybius writes that Scipio “led out his troops and drew them up along the brow of the hill,” taking his time. At this point Scipio launched his surprise: he divided the heavy infantry into two units; he led the right wing and Laelius the left. They worked their way up the base of the hill on both sides, then charged up to the flanks of the shelf. “While the manoeuvre was in progress,” writes Polybius, “Hasdrubal was still engaged in leading his troops out of the camp. Up to this moment he had waited there, trusting to the natural strength of the position and feeling confident that the enemy would never venture to attack him.”22

Pressured from the front and surprised on the flanks, the Carthaginian forces panicked. Hasdrubal made a hasty exit, his heavy infantry covering his retreat as he left his camp with the war chest and elephants. He waited for those who escaped to join him, then marched north for the Pyrenees to join his brother Hannibal in Italy. Scipio, unsure of the location of Mago Barca and Hasdrubal Gisgo, decided against pursuing the defeated Carthaginians. Instead, he once again divided the spoils of the captured camp and entertained the new stream of Spanish chieftains who came to pledge their support. Livy describes a meeting between the fleeing Hasdrubal and the other two generals, in which they exchanged intelligence and laid out potential actions. Hasdrubal marched for Italy to join Hannibal. He never reached him, however, as he was defeated and killed at the Metaurus River in northern Italy by Gaius Nero, whom Scipio had replaced in Spain.

Scipio introduced two new aspects to Roman warfare at Baecula. First, he held the center with light troops and a relative handful of supporting infantry; the heavy infantry had always held the center. This shows that the Romans had at last trained their lightly armed troops properly. Scipio gets the credit for using them for the first time effectively in battle.23 Second, he engaged in maneuver, striking both enemy flanks with heavy infantry. Hasdrubal was certainly surprised at the arrival and the make-up of the flanking units, which hit him before he could properly deploy his main force.

Nonetheless, the Battle of Baecula falls well short of being decisive. The two flanking movements were not coordinated (not surprising given the broken terrain and the novelty of the maneuver). Further, once the Romans reached the plateau there was no quick reestablishment of control over the units, thus giving Hasdrubal the opportunity to make an orderly withdrawal.24 Thus, Scipio failed to properly concentrate his forces; he did not exploit the victory, since so many of Hasdrubal’s troops escaped; and he did not engage in pursuit. Though it was not a complete victory, the battle was a major accomplishment, for Scipio had to dislodge an enemy from such a strong position. This gave the Romans the momentum to go on to bigger and better things as their training and execution matured over time.25

Scipio’s army had been the larger of the two (35,000 to Hasdrubal’s 25,000) but the numbers were negated by the strength of the Carthaginian position. Livy says Hasdrubal lost 8,000 in the battle and agrees with Polybius’s report of Scipio capturing 10,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Most modern historians find those numbers exaggerated. Some think the numbers must include Spaniards who quit in the middle of the battle or changed sides. Others say that the numbers given by the ancient historians would be correct were the population of Baecula itself included.26 If Hasdrubal’s plan in 208 had been to assist Hannibal in Italy, then he risked being unable to reinforce his brother if he fought Scipio and lost. Had Hasdrubal won, of course, facing Scipio would have been the wise decision as he would have regained Spain for Carthage.

Whether or not Livy is correct concerning Hasdrubal’s conference with his compatriots, the other two armies made no attempt to counter Scipio’s victory and the resulting local alliances his victory gave him. According to Livy’s account, the three decided thus: Hasdrubal Barca would proceed to Italy with as many Spanish troops as he could gather in order to keep them away from Scipio’s influence. Mago should give his army to Hasdrubal Gisgo, then travel to the Balearic Islands to recruit more mercenaries, particularly slingers, their specialty troops. Gisgo would take the Carthaginian forces to the far west coast—away from Scipio’s area of rumored largesse with the Spanish tribes. Last, the Numidian cavalry general Massanissa should take 3,000 cavalry and harass pro-Roman towns along the frontier. In short, the Carthaginians would initiate no action that year. Scipio gave them little choice, anyway. Having won at Baecula, he withdrew to his base at Tarraco again and spent the remainder of the year there.

The following year, 207, the two sides did little more than spar with each other. Hasdrubal Barca’s replacement, Hanno, tried to keep up recruiting among the Celt-Iberian tribes of Spain’s central region and lost a small battle with Scipio’s brother Lucius, while Hasdrubal Gisgo redeployed in the area around Baecula but refused battle with the Romans, retreating into a number of fortified towns. It almost seems as if the strategic situation in Italy was seeing its mirror image in Spain, with the Carthaginians engaging in Fabian tactics. Scipio, unable to maintain his army in the countryside too far away from his bases, did not press.

IN 206, HOWEVER, HASDRUBAL GISGO was back on the move—into the Baetis River region west of Baecula. He’d reportedly gathered 70,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 32 elephants and seemed to be throwing down the gauntlet to Scipio. Livy asserts that the Carthaginians numbered only 50,000. Whatever the case, given the nature of Scipio’s battlefield maneuvers, as we shall see, he seems to have been heavily outnumbered. The Roman leader responded by sending out subordinates to round up Spanish allies. He eventually fielded an army of about 45,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. About half Scipio’s force was Roman or Latin, the other half locally recruited, including the tribes that had turned against his father and uncle and caused their deaths. “For without their allies the Roman forces were not strong enough to risk a battle,” as Polybius observed. “Yet to do so, in dependence upon the allies for his hopes of ultimate success, appeared to him to be dangerous and too venturesome. In spite however of his perplexity, he was obliged to yield to the force of circumstances so far as to employ the Iberians.”27 The loyalty of Spanish tribes, or their perceived loyalty, figured into his battle plan.

The exact location of what came to be called the Battle of Ilipa is subject to debate. The best guess is that it took place somewhere in the neighborhood of modern Alcala del Rio, north of Seville. An alternate location is nearer the site of the Battle of Baecula. There is also an “Ilipa” near the river south of Castulo, much further east, which is another possibility. Both Polybius and Livy locate the battle there, and there is some independent evidence for such a town.28 The description of the ground is fairly generic: Polybius says Hasdrubal’s army dug their “entrenchment at the foot of the mountains, with a plain in front of him well suited for a contest and battle” while Scipio “pitched his camp on some low hills exactly opposite the enemy.”29

Mago Barca, subordinate it seems to Hasdrubal Gisgo at this battle, launched a spoiling attack with his cavalry (accompanied by some Numidians under Massanissa) just as the Romans were setting up their camp. In his study of Scipio, Basil Liddell Hart writes that the Roman general was, “as usual, imbued with the principle of security,” and had foreseen such a possibility by hiding his cavalry in the shelter of a hill and keeping them prepared.30 The Romans put up a good fight (dismounted at times) and through surprise and toughness repulsed the Carthaginians, then pursued them. Though there is no written evidence for this, it seems as if Scipio had trained his cavalry in new tactics along with his infantry. They were now vastly better than the cavalry forces the Romans had fielded before. This action had an impact on the morale of both sides.

After the initial skirmish, both sides proceeded to a battle of nerves. Every afternoon Hasdrubal deployed his men for battle: African infantry in the center, Spanish infantry on the wings, fronted by elephants and flanked by cavalry. Every day, later in the afternoon, Scipio deployed his men: Roman infantry in the center, Spanish infantry on the wings flanked by cavalry. As Livy writes, “The Carthaginians would always be the first to lead their troops from camp, and the first to sound recall when they were weary of being on their feet. There was no charge, no spear thrown, and no battle-cry raised on either side.”31 This went on for several days. Finally, when Scipio was sure everyone knew what to expect, he shook things up. One evening after withdrawing from the field he sent word quietly around the camp: get up early and eat, then prepare to deploy at first light.

The next morning the Romans were up early, fed, and ready to go. Scipio had been at his father’s side, if not in actual combat, at the Battle of the Trebia River in 218 when Hannibal had done precisely the same thing on a freezing December morning. When the Carthaginians awoke and found themselves facing a Roman army ready for battle, they rushed to deploy. As they did so, they came under fire from the Roman velites, which kept them focused on their own protection. Scipio, meanwhile, had deployed his Spaniards in the center, not his Romans, who were now on the flanks with the cavalry. When the Carthaginians had arrayed themselves for battle and seen the unexpected formation, it was too late to shift their own. The battle did not begin, however. The opposing skirmishers (with the two main forces perhaps half a mile apart) kept up their respective fire, pelting the enemy with javelins and stones. The hour drew toward noon, and the Carthaginian soldiers began to feel the heat of the sun and the hunger in their bellies.

Scipio’s next move is what makes the Battle of Ilipa unique in the annals of combat, and so complex that even Polybius can’t do it justice. Indeed, illustrated depictions of what happened vary from historian to historian. It seems that the Roman skirmishers, having been withdrawn in normal fashion through maniples, reformed at the rear flanks so the flanking units were three lines deep—a line of heavy infantry maniples in front, a line of light infantry second, a line of cavalry third. The entire army then proceeded to move forward, line abreast. Keeping the Spanish infantry in the center, marching forward at half time, Scipio ordered his Roman cohorts on either flank to face outward. Scipio’s actions on the right flank were mirrored by Marcus Junius Silvanus and Lucius Marcius on the left. Having executed a right-flank march, they proceeded until they were even with the ends of the Carthaginian lines. Scipio then ordered a column-left march. (Some historians say the movement up to this point was actually done in echelon or in two moves, half-right march then half-left march, to end up at this point.) His unit was now perpendicular to the enemy (heavy infantry maniples on the left, velites in the center, cavalry on the right) and moving in column much more quickly than the Spaniards. At one stade (600 feet) from the enemy the column halted. The columns then faced outward, heavy infantry facing left, light infantry and cavalry facing right. At this point Sciopio had each line wheel toward the enemy (heavy infantry right-wheel march, light infantry and cavalry left-wheel march). When it was all over, he had his heavy infantry in line facing Hasdrubal’s Spanish infantry and the light infantry and cavalry continuing the line past the enemy flanks.

Now the actual fighting started. The velites and cavalry continued to wheel until they struck the Carthaginian flank and rear. “When these troops were at close quarters the elephants were severely handled,” writes Polybius, “being wounded and harassed on every side by the velites and cavalry, and did as much harm to their friends as to their foes; for they rushed about promiscuously and killed every one that fell in their way on either side alike.”32 Scipio’s infantry struck at the same time Hasdrubal’s Spanish allies were collapsing. The Carthaginians in the center could do nothing; to turn and assist their Spanish allies would expose their flanks to Scipio’s oncoming Spaniards; to charge forward would open their flanks and then rear to the Roman-Latin troops. The Carthaginian force at first stood firm and began to withdraw in order, but as the Spanish troops on the wings began to buckle the units in the center collapsed and fled. Polybius noted that had not “Providence interfered to save them, they would promptly have been driven from their camp too. A sudden storm erupted, and it was so heavy that it forced the Romans back to their own camp.”33

Polybius leaves off his description of the battle at this point, but Livy continues with a description of the Carthaginian troubles. Hasdrubal watched while Spanish tribes fled, and he soon learned of garrisons in the area surrendering to the Romans. The following night he led the rest of his men westward but could not make good his escape to Gades (Cadiz), since the pursuing Roman cavalry and light infantry blocked his crossing of the Baetis River. The retreat, says Livy, became flight, and only got worse as the rest of the Roman army began to catch up to the pursuit. “After that it was no longer a battle; it was more like animals being slaughtered—until their leader authorized flight by personally making off to the nearest hills with approximately 6,000 poorly armed men. The rest were cut down or taken prisoner.”34 The 6,000 fugitives tried to defend themselves at a hastily built fort, but were easily surrounded. Hasdrubal abandoned his men and reached Gades, where he caught a ship for home.

Much had changed. Mago’s initial spoiling attack probably would have done some damage had the battle taken place a few years earlier, but the Roman cavalry had honed their skills under Scipio’s command and their counterattack drove the enemy from the field. Both sides demonstrated for a number of days before the actual fighting began, an action of which Scipio took advantage by a deployment employing surprise both in timing and in alignment of his forces. Next, his deliberate drawing out of the initial skirmishing in order to use heat, hunger, and thirst to weaken the Carthaginian troops exhibited his control of tempo. Whether at Trebia or elsewhere, he had somehow absorbed the lesson of subjecting his opponent to hunger, fatigue, and temperature.35 Indeed, the U.S. Army’s definition of “concentration” is almost a description of Scipio’s maneuvers: “Attacking commanders manipulate their own and the enemy’s concentration of forces by some combination of dispersion, concentration, deception, and attack.”36 And although unable to exploit the victory owing to the heavy rain (also reminiscent of Trebia), he made up for it with relentless pursuit. Liddell Hart comments that the pursuit had “no parallel in military history until Napoleon,” who saw it as “one of the supreme tests of generalship.”37

Scipio took a major risk in using these maneuvers at Ilipa. Could his men perform the complicated marching and wheeling he asked them to do in the face of the enemy? Livy’s description of the maneuvers is much shorter and simpler and says nothing about an attack in column. He says merely that Scipio ordered the commanders on the opposite wing to follow his lead by extending their units outward, to engage the enemy with their light infantry and cavalry before the centers could meet, “and with these they advanced swiftly, the rest of the troops following at an angle.”38 Except for his comment about the “angle” it would appear (to Livy) that the wings marched line abreast across the field, but simply did so more quickly than the Spanish mercenaries, creating a refused center. It is possible that the advance in column was done in the interests of speed, for a column can advance more quickly than a line, and Scipio was anxious to initiate contact with his Romans before there was any possibility of his potentially unreliable Spanish allies being engaged in the center by Hasdrubal’s more reliable Africans.39 As Goldsworthy notes, “The details of the manoevre performed by the Roman army has, like so many other aspects of the war, been endlessly debated by scholars.”40 His illustration shows the two Roman wings attacking line abreast at about a thirty degree angle toward the Carthaginian flanks.

Whatever the truth of the matter, it was an extremely complicated move, one that depended on the enemy doing nothing but watch it unfold. As Liddell Hart says, “The only defence is that Scipio managed to carry it off…. Scipio ran the risk, hoping Hasdrubal would hesitate, which, in fact, he did.”41

So why did the Carthaginians do nothing? Livy describes Hasdrubal as “the greatest and most famous general of the Carthaginians after the Barcas.”42 His most recent translator, J. C. Yardley, however, blames Hasdrubal, asking why he simply stood in position and allowed all this to be done in front of him. All the fancy maneuvering had left gaps in the Roman line, and exposed their flanks to the Carthaginians. “But on all the evidence Hasdrubal son of Gisgo was a hopeless general.”43 Just the fact that his army had been wrong-footed by the early Roman deployment may have paralyzed Hasdrubal, as possibly he feared some other deception and simply bided his time when he should have been launching an attack of his own.44

SPACE DOES NOT ALLOW ANY FURTHER DESCRIPTION of Scipio’s actions in other battles, though he continued to show originality in battles around Carthage in 204–202. The epitome of his career was his confrontation with the master, Hannibal himself, at Zama, not far from Carthage. The student won, perhaps fittingly, with a double envelopment of Hannibal’s army, though some sources opine that had the two armies been of equal quality the outcome may have been different. He fought in Gaul after that and spent much time in Roman politics. Politics proved his ultimate undoing. As Goldsworthy recounts, “Africanus was a poor politician who had difficulty achieving his objectives in the Senate quietly and without confrontation.… Depressed by the ingratitude of the State he had served so well, [he] went into voluntary exile in his villa in Liternum, where he died soon afterwards in 187.”45

Scipio fulfills so many of the eleven principles of war that it is very difficult to pick two or three as examples. Perhaps one of the most important is his focus on the objective. When he arrived in Spain, many in Rome may have been expecting him to do little more than engage in a holding action to keep supplies and reinforcements from reaching Hannibal in Italy. If so, he disappointed them. He grasped two major concepts about how to fight in Spain. First, he knew that he could not win without a strong and secure base to maintain his lines of communication with Rome. Second, he knew that he could not defeat a united Carthaginian army. Object number one was accomplished with the capture of Novo Carthago. To achieve the second objective, he made sure he fought only separated armies: Hasdrubal Barca at Baecula and Hasdrubal Gisgo at Ilipa. After both victories he withdrew to the east coast rather than try to stretch his logistics by operating in the countryside at too great a distance from his base. Winning a series of limited objectives added up to the expulsion of the Carthaginians from Spain.

In addition, Scipio mastered the art of the maneuver. By breaking with traditional Roman tactics he caught the enemy unaware of what a new Roman army could do. The Battle of Ilipa was a tactical masterpiece, showing how a small army can defeat a larger one by shaking things up and using maneuver to keep it off balance, a capability he developed by introducing a more flexible formation.46 Though the capture of Novo Carthago did not involve innovation, the surprise attack across the lagoon was at the time a most un-Roman thing to have done. Still, all three of the battles discussed here show a single theme, as described by Liddell Hart: “In the sphere of tactics there is a lesson in his consummate blending of the principles of surprise and security.”47

That brings us to security. Scipio illustrated from the beginning that he understood this concept fully. It was almost certainly driven home for him by the father’s and uncle’s deaths by desertion. So before the march on Novo Carthago he shared his plan with no one but Laelius, his chief of staff, who happened to be a childhood friend. Even as he accepted the pledges of tribe after tribe in the months and years following, he never fully trusted them. This is best shown at Ilipa, where he needed the Spaniards but determined not to depend on them. As Polybius observes, “He was obliged to yield to the force of circumstances so far as to employ the Iberians; but he resolved to do so only to make a show of numbers to the enemy, while he really fought the action with his own legions.”48 Also, by withdrawing to his base after his victories, he made it much more difficult for the Carthaginians to gather intelligence on Roman actions or plans.

SCIPIO’S SUCCESS WITH his new tactics proved to be vital to the overall change in the Roman military. The fighting style Hannibal introduced was embraced by Scipio’s generation. By the end of the Second Punic War, the Roman army had developed from an unwieldy hoplite-style phalanx into a highly mobile force in which even heavy infantry were capable of rapid and independent maneuvers. The Romans learned the use of lightly armed troops and cavalry, and, above all, the concept and practice of combined arms.49 Not just fighting style but the craft of generalship itself blossomed, and Scipio was the first to illustrate its advantages. Scipio learned well, so well that he never became predictable. Polybius said it best: “For while a general ought to be quite alive to what is taking place, and rightly so, he ought to use whatever movements suit the circumstances.”50