General in the Service of the Emperor Justinian I of the Eastern Roman Empire

[A] most winning character, was bold to the verge of rashness, resourceful and of an inventive mind, a general always ready to make the most of the inadequate means allotted him by his parsimonious master.

—J. F. C. Fuller, Military History of the Western World

BELISARIUS’S BIRTH DATE is a matter of speculation, as is his upbringing. In his classic nineteenth-century biography of the general, Philip Henry Stanhope, Lord Mahon, argues that the description offered by Procopius of a “lately bearded stripling” should make him about twenty years old when he first appears in history as a member of General Justinian’s private guard, a couple of years before Justinian assumed the throne in 527.1 Procopius, who was Belisarius’s secretary and contemporary, and a historian of Justinian’s wars, writes that Belisarius came from the same town as Justinian, Germania in Illyria.2 Most sources claim a humble birth, but Mahon argues for one much higher, pointing out his possession of estates at an age when he could not possibly have achieved sufficient glory and wealth from his wars to have afforded them.3 Further, Belisarius’s parents are not denigrated in Procopius’s Secret History, as are those of his wife, Antonina, the Emperor Justinian, and Empress Theodora.

Since Justinian was born in 483, it is highly unlikely that the two knew each other until Belisarius joined the bodyguard. Procopius gives us the most complete story of his career but no hint how a member of the guard came to Justinian’s attention. According to Edward Gibbon in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, “He served, most assuredly with valour and reputation, among the private guards of Justinian; and, when his patron became emperor, the domestic was promoted to military command.”4 His first assignment was as cocommander with Sittas, about his age and brother-in-law to Theodora. Assuming the two were friends in the guard, this could well have been how he came to the attention of the man who would be emperor. Belisarius and Sittas were sent on a raid in 526 into Persarmenia, a region long disputed between Romans and Persians, where they succeeded in extensive pillaging and capturing numerous prisoners to obtain slaves.5 On a second raid they were not so lucky, losing what appears to be a skirmish to the Persian commanders Narses and Aratius, both of whom soon defected to Justinian. Procopius certainly downplayed the encounter, saying merely that the Persians “joined battle with the forces of Sittas and Belisarius and gained the advantage over them.”6 Soon after these engagements Justinian assumed the throne in Constantinople (1 April 527) upon the death of his uncle Justin.

As emperor, Justinian inherited a long-running conflict between his empire and that of Sassanid Persia. In the wake of Alexander’s defeat of the Achaemenid Empire, the Persians absorbed some Hellenistic culture while under the sway of the Successors. As the descendants of the great Macedonians began to fade in the wake of the rising Roman Empire, the Persians found themselves under the rule of the Arsacid Dynasty of Parthians, horsemen from the north. The Parthians began to restore some unity to the region and eventually faced off against the expanding Roman Empire. With a frontier generally regarded as the Euphrates River, Parthians and Romans engaged in decades of territorial give and take, although the Parthians tended to be the lesser of the two powers. In the early third century AD, the Parthian power had declined sufficiently that the Persians themselves rose up and defeated them. This led to the establishment of the house of Sassan, or Sassanid Dynasty. They reestablished the old Achaemenid titles and ambitions, which included reoccupying lands ceded to Rome. Although Eastern Roman troops kept the Persians at bay, they could not reimpose their will. Emperors Valerian and Julian the Apostate lost their lives trying, and in 363 Emperor Jovian signed a necessary but humiliating treaty with Persia that obliged the Romans to grant some territorial concessions. From this point forward, the Eastern Roman Empire gave up trying to conquer Persia.7

From 363 until the reign of Justinian, the relationship remained a balance of power. In 387 Rome and Persia divided Armenia between the two empires and in 422 signed a treaty that came to be called the Hundred Years’ Peace. During that time, the Persians dealt with internal religious difficulties when Zoroastrian magi tried to exert significant influence in the government, as well as countering threats from the White Huns invading from the northeast. The Huns also threatened to invade via the Caucasus between the Black and Caspian Seas. This area had originally been jointly defended, but gradual Roman withdrawal had led to Roman subsidies to hold up Rome’s end of the defense agreement.

Those payments laid the foundation for the Roman-Persian conflict in Justinian’s reign. The Persian failure in 483 to turn over the frontier city of Nisibis (as called for in the treaty of 363) led to Roman refusal to pay its share for the Caucasus defense. The Roman emperor Anastasius I (r. 491–518) built up defenses in Mesopotamia and Armenia, in particular the city of Dara on the Euphrates, not far from Nisibis. Between 502 and 504 the two sides engaged in serious warfare, with the Persian king Cavadh gaining early, temporary victories in Byzantine lands. A few setbacks in 504, coupled with a major Hun invasion, forced him to sue for peace in 505. A seven-year truce followed, which was never renewed, but never abrogated. During the Hunnic-Persian war, the Byzantines further irritated the Persians by allying themselves with the Caucasus kingdoms of Lazica and Iberia.

TWO MAJOR FACTORS WERE INVOLVED in radically changing the Eastern Roman army by the early sixth century. First, the nature of the Roman citizen was vastly different than it had been in the days of the republic. Previously, military service had been a duty that adult males engaged in as an aspect of citizenship—any threat to the government and people had to be met, no questions asked. Usually no more than a season or a year of service was necessary to beat back most threats. By the end of the republic, the army was a long-service career followed mainly by the urban poor. A few centuries into the empire, however, and the attitude had changed again. Few adult Roman males answered the call to duty, for military service now involved years in foreign lands. Citizens in many trades were exempt from being drafted, and military service was so unpopular that it was not unknown for men to mutilate themselves to avoid being drafted into service.8 Thus, the army became increasingly dependent on troops recruited from the hinterlands or even from former enemies. Decreased manpower across extended frontiers required more defense than offense, so the empire relied on limes, a cordon defense, or string of forts and fortified cities. These protected citizens and trade routes where there were no natural obstacles. Justinian built limes in amazing numbers and size.9 Backing this line were mobile fighting forces designed to relieve the strong points and pursue enemies.

The second factor was the nature of the enemies themselves. Both the eastern and western empires were pressured by Asian or Eurasian “barbarian” forces that depended on mobility. Invading armies increasingly were mounted rather than made up of foot soldiers. Although the traditional Roman legion could stand up to cavalry, those troops had been heavy infantry trained by years of service. Less motivated and smaller forces (especially those raised on the frontier with no strong bond to Rome) were less likely to embrace the discipline necessary to stand fast against charging horsemen. Hence, both halves of the empire needed veteran forces that could rapidly respond to fast-moving threats and inflict damage on armies made up of soldiers who were often raised in the saddle. The influx of frontier manpower into the army meant the incorporation of peoples who had the same cavalry-oriented upbringing and experience and somewhat less dependence on the traditional infantry.

Thus, the Eastern Roman Empire in particular began to build its army around heavy cavalry and light infantry, which could move faster than loot-laden raiders on foot. The speed of the cavalry and light infantry replaced the traditional power of the Roman heavy infantry with even more flexibility than Caesar’s maniples.10 The heavy cavalry cataphracti wore chain mail to the knee or longer and were armed mainly with lances and bows. This allowed them to withstand enemy arrows while attacking either infantry with their lances or cavalry with their bows. In some cases the horse was armored as well. Given the difficulty of training and the expense to equip a soldier with both weapons, it is likely that the Byzantine horseman had his greatest use in shock action. Thus, the lance was primary and the bows provided versatility if necessary.11

Most of the cavalry was recruited from the fringes of the empire. Once the Hunnish empire collapsed not long after Attila’s death, Hun horsemen joined the Roman service, as did Alans from the Iranian steppes and Germanic Goths. Southeastern Europe also became a breeding ground for horses and horsemen, as in the days of Philip and Alexander.12 Although most of the “barbarian” troops had been expunged from the army in 400 owing to fear of disloyalty, Justinian had no such qualms in his desire to build an army large enough to reestablish the Mediterranean empire. These “federates” (foederati) of foreign (and ultimately domestic) troops were recruited and led by their own commander, who swore loyalty to Justinian. Such a semiprivate army was called a comitatus. The troops were loyal to their commander, requiring Justinian to be certain that the commanders were loyal to him, often a problem in Byzantine history.13 The horse archers possessed the long-range effectiveness of Hunnic warriors with their famous compound bows, but could also fight well at close quarters.14 Also at this time, aristocrats raised units of elite bodyguards (bucellarii), whether federate or Byzantine, that could be available to the emperor on the same terms as the federates.15 For example, Belisarius’s bodyguard numbered as many as 7,000.

The light infantry carried small shields for protection and swords or axes for close combat, but their primary weapon was the bow. The leading ranks at least were well armored and supplied with large shields to protect against enemy arrows and javelins. All soldiers were instructed in the use of the bow, making long-range warfare the primary method of opening a battle, with the heavy cavalry breaking through whatever weakened areas appeared.16 Although some enemies were extremely effective horse archers, the standing Byzantine archer had the stability to use stronger bows and therefore engage at greater ranges. Often consisting of limitani (frontier militia), the light infantry were of irregular quality. Romano-Byzantine heavy infantry were fewer in number, but equipped with heavier armor, sword or axe, and a spear. They played the traditional role of breaking enemy assaults and protecting the archers. Although these forces comprised a much smaller percentage than earlier Roman armies, many authors comment on their continued importance in sixth-century battles. During Justinian’s reign, the basic tactical unit remained the phalanx, although it was a more flexible unit than that of the classical Greeks. The standard formation was described as 512 men wide and likely twelve ranks deep. That would make 6,144 soldiers, a bit larger than the traditional Roman legion.17 Contemporary authors are of the opinion that a well-trained and disciplined infantry was key to Roman warfare no matter the ratio to the other arms,18 and they were valuable as protection for the cavalry as well as the light infantry.19

The army generally deployed with infantry in the center and cavalry on the flanks, with light infantry slingers in front if an enemy cavalry charge appeared imminent. After long experience against Eurasian cavalry armies, the Byzantine cavalry developed their own method of deployment. Two-thirds of the unit would be deployed forward in ranks eight deep in the center and four deep on the wings. A second line would form up 400 meters to the rear. The horses along the front line were armored. Each division consisted of cursores armed with bows for the offense, protected by defensores who closely followed up their attacks. Such tactics remained in use around the Mediterranean for almost a thousand years.20

The Sassanian Persian army had undergone some serious reforms in the wake of defeats at the hands of the Hephthalite (White) Huns in the 480s. By the turn of the sixth century, it was little different in makeup from the Romano-Byzantine forces. The dominant arm was cavalry, made up from the “free” citizens, the minor aristocracy. It was lighter than the Byzantine cataphracts but made up about the same percentage of the army. Horse archers were incorporated from frontier societies like the Huns and Armenians. Mercenaries and subject peoples would have furnished auxiliary cavalry in some numbers. Three thousand Sabir Huns are said to have been recruited for the attack on Satala in 530, while the Kadishaye (Kadiseni) were the primary unit of the Persian right wing at the Battle of Dara against Belisarius that same year.21 This lighter cavalry provided archery support for the heavy cavalry, known to the Romans as the clibanarii22 and to the Sassanians as the Savaran,23 which were armored almost exactly like the cataphracts. The Parthian heavy cavalry had a larger scale-armor blanket for their horses, but by Sassanian times this seems to have been reduced to cover just the front half of the animal’s body. The heavy cavalry used the lance as their main weapon, although they also carried multiple hand weapons for close-in fighting should circumstances dictate. By the reigns of Khavad and Khusrow, who were contemporaries of Justinian and Belisarius, the Savaran had abandoned the bow altogether. The elite of the Sassanian army were, as in ancient days, called the Immortals and have been regarded as being as good as or better than the Roman troops.24

The Persian infantry was the weakest arm. It was scorned by the Romans. Procopius quotes Belisarius in his prebattle speech before Dara: “For their whole infantry is nothing more than a crowd of pitiable peasants who come into battle for no other purpose than to dig through walls and to despoil the slain and in general to serve the soldiers. For this reason they have no weapons at all with which they might trouble their opponents, and they only hold before themselves those enormous shields in order that they may not possibly be hit by the enemy.”25 Modern historians echo that attitude, pointing to the performance at the Battle of Dara, when the paighan (infantry) dropped their shields and abandoned the field after the Savaran (heavy cavalry) were defeated.26 These were peasant conscripts with neither training nor motivation, forming a rear guard and regarded as next to useless.27

Without a contemporary Persian historian like Procopius, exact details of Persian tactics have to be pieced together from Romano-Byzantine and later Muslim sources. It appears that they did not alter their fighting methods in the wake of defeats at Hunnic hands. Roman sources describe the typical Sassanian battle deployment as dividing an army into a center, ideally on a hill, with two wings, with spare horses being kept at the rear.28 Some sources describe a cavalry front with infantry archers on the left wing. In some cases elephants are mentioned, though not in any battle in which Belisarius fought. Later sources describe an infantry center with cavalry wings and a force of elite reserves, or an arc of troops in the center flanked by cavalry protecting the herds on one side and the baggage on the other, with a hospital in the center rear. Combat was straightforward, dominated by the heavy cavalry, with little in the way of flanking movements or deception.

IN A MOVE TOWARD RECONCILIATION with the Byzantines, the Persian king Cavadh in 523 or 524 offered his fourth and favorite son, Chosroes, to Emperor Justin for adoption in order to protect him from jealous older brothers at Cavadh’s death. The Romans seriously considered the offer, but ultimately rejected it as a potential threat to imperial succession; Cavadh took the refusal personally. In 524 he launched a campaign that conquered Iberia, provoking Roman counteroffensives in Persian Armenia; these were the previously mentioned attacks led by Sittas and Belisarius. Their defeat at the hands of Narses and Aratius in 526 apparently had no ill effects on Justinian’s opinion, and he was the power behind Justin’s throne. As Lord Mahon argues, “We may conclude that the personal conduct of Belisarius, on the last occasion, was not only free from blame, but even entitled to praise, since we find him, immediately afterwards [527], promoted to the post of Governor of Dara.”29 It is not recorded how Belisarius performed personally in that battle, but another in 528 had no better result. This was an attack in support of a Byzantine fort being erected at Thannuris, on the frontier of the southern front.30 Procopius writes merely that “a fierce battle took place in which the Romans were defeated, and there was a great slaughter of them.”31 A contemporary account by Zachariah of Mitylene is somewhat less terse but more unflattering: when the Persians learned of the Roman approach, “they devised a stratagem, and dug several ditches among their trenches, and concealed them all round outside by triangular stakes of wood, and left several openings.… They did not perceive the Persians’ deceitful stratagem in time, but the generals entered the Persian entrenchment at full speed.… Of the Roman army those who were mounted turned back and returned in flight to Dara with Belisarius; but the infantry, who did not escape, were killed and taken captive.”32

In spite of this setback, in 529 or 530 Belisarius was named master of the soldiers in the East (Magister Militum per Orientem), in command of one of the empire’s five field armies. (He also at this point took on Procopius as his secretary-aide, leading to the firsthand accounts of Belisarius’s campaigns.) The flash point for conflict was on the upper reaches of the Tigris at the Byzantine city of Dara, not far from the Persian stronghold at Nisibis. He made his headquarters at Dara, where he was ordered to repair the city’s defenses as a counterbalance to the nearby Persian stronghold at Nisibis.

In the wake of these recent military reverses, Justinian was of a mind to negotiate with King Cavadh, who had threatened war if the gold for the northern frontier defense he had long demanded was not forthcoming: “But, as pious Christians, spare lives and bodies and give us part of your gold. If you do not do this, prepare yourselves for war. For this you have a whole year’s notice, so that we should not be thought to have stolen our victory or to have won the war by trickery,” wrote the contemporary chronicler John Malalas.33 Cavadh, however, did not wait a year. When Justinian’s envoy was on his return trip to the Persian capital, he stopped at Dara. A Persian army was already approaching.

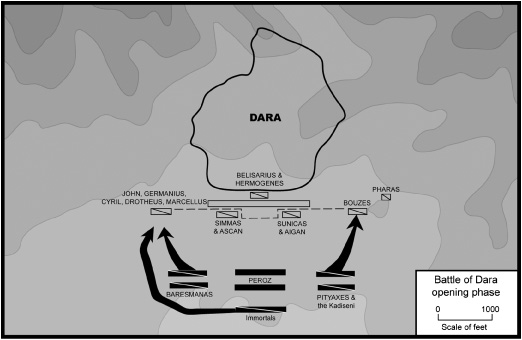

BELISARIUS COMMANDED 25,000 MEN AT DARA, probably about one-third of them cavalry. Fearing the potential conflict, he had scoured the countryside for manpower to reach that number, but the discipline of the force was hurt, and their spirit broken by their former setbacks.34 The cavalry were in finer fettle, with at least 1,200 Huns and 300 Herules (a tribe of Scandinavian descent). Belisarius had sufficient time before the Persian approach to prepare the battlefield. Perhaps remembering his own disaster against Persian trenches near Thannuris two years earlier, he had a trench dug parallel to the city walls. According to Procopius, it was “a stone’s throw” away from the city wall. The trench was neither straight nor continuous, but had several crossings left for troops to advance or retreat across it. “In the middle there was a rather short portion straight, and at either end of this there were dug two cross trenches at right angles to the first; and starting from the extremities of the two cross trenches, they continued two straight trenches in the original direction to a very great distance.”35

To the left flank were an unknown number of heavy cavalry behind a hill under Bouzes accompanied by the 300 Herules commanded by Pharas. To their right, stationed at the trench’s right angle, were 600 Hun light cavalry under Sunicas and Aigan. On the other side of the trench cutout, the formation was a mirror image, less the flanking hill. Another unidentified number of heavy cavalry were deployed on the Roman right led by a number of cocommanders under the overall command of John, son of Nicetas. The infantry lined up behind the ditch, with Belisarius and his cocommander Hermogenes behind them, almost certainly leading their respective bucellarii, which could have numbered a few thousand. Procopius does not mention any light infantry deployed as skirmishers along the front.

The inset section of the trench, in the center, is described only as at right angles to the lengthy main trench; Procopius does not make it clear if that section is set forward or to the rear. Oman, Art of War in the Middle Ages (pp. 28–29), says the line was refused, and most maps show it set back, toward the city, but the Harvard edition of Procopius (p. 103), as well as Goldsworthy (Name of Rome, p. 412) and Greatrex (Rome and Persia, p. 172), shows it extending toward the Persian lines. Given that the main section of line was “a stone’s throw” from the city walls, it seems unlikely that the entire body of infantry as well as Belisarius’s bodyguard cavalry could have fit in the area if the trench section were refused. To do so would most certainly have obliged the infantry and possibly the cavalry to form up in two sections, which one would assume Procopius would have noted.

The Persian force initially numbered 40,000 under the command of Peroz Mihran.36 He marched to Dara with such confidence that he “immediately sent to Belisarius bidding him make ready the bath: for he wished to bathe there on the following day.”37 He apparently had second thoughts as he came within site of the Roman force and found them formed up, ready for battle. Like the Romans, he placed his infantry in the center and his cavalry on the flanks. Again, specific numbers are unknown, but the Immortals38 were placed in reserve. The others were stationed in two ranks so the rear units could rotate into battle as the leading units lost manpower or ran out of arrows. As it grew later in the day, Peroz probed the Roman left with a cavalry squadron. They enjoyed quick success until they discovered too late that the Romans were engaging in the Parthian tactic of the feigned retreat—apparently the Persians had not considered they could be beaten at their own game. Rather than follow this up with a major assault, the Persians tried another, more psychological ploy: the single combat, in which an individual soldier from either side met and fought with no intervention from their respective armies. This, too, failed the Persians when a Roman volunteer, a wrestling instructor who was not even a part of the army but an attendant to the cavalry commander Bouzes, handily defeated two Persian warriors. Peroz would have to bathe outside the city. The Persians withdrew to their camp at Ammodius, just over two miles away.

The next day was taken up in an exchange of messages, as well as a Persian reinforcement of a further 10,000 troops from Nisibis. Belisarius and Hermogenes, the civilian governor in Dara, offered a peaceful resolution to the confrontation, arguing that since both kings desired peace and negotiators were at hand, Peroz should not be seeking battle. Asserting that the greatest of blessings was peace, Belisarius insisted that Peroz should avoid a fight “lest at some time you be held responsible by the Persians, as is probable, for the disasters which will come to pass.”39 Peroz’s return missive doubted Roman sincerity. Two more messages invoked God on the Roman side and the Persian gods in return. Again, Peroz alerted Belisarius that a bath, as well as dinner, was expected inside the city.

On the third day, each commander gave his troops a suitably inspiring motivational address before the armies once more formed up outside Dara’s walls as they had at their first meeting. As the deployment was taking place, Pharas, the Herule commander, suggested to Belisarius that he detach his unit and station his 300 cavalry behind a hill on the far left wing. This would give the opportunity for a surprise attack on the advancing Persian cavalry flank where they could do them the greatest harm.40 Belisarius quickly agreed. Once the armies faced each other, however, nothing happened. As Goldsworthy observes, the “Roman formation was geared to receiving a frontal attack and, with the wall of Dara so close behind them, such an attack was the only viable option open to Peroz if he wished to take the city.”41 Hence, Belisarius was not about to do anything other than await the attack. Peroz wanted to delay the battle until at least noon, hoping to force the Romans to miss their midday meal and weaken them. (The Persians normally ate later in the day.) This delay apparently did not have the desired effect.

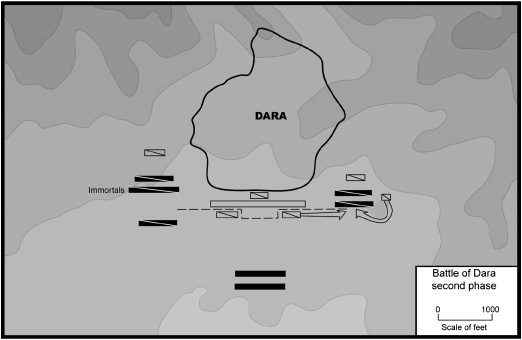

The battle started with an exchange of arrows, but apparently only on the flanks. Procopius makes no mention of any fighting taking place in the center. The Persians had the advantage in numbers, as well as the rotation of fresh archers to the front; harking back to Thermopylae, Procopius claims the arrows darkened the sky. Unfortunately for Peroz, the Romans had a strong wind at their back, so the effect of the barrage was minimized. The Persians had been advancing while firing, for Procopius writes that as the arrows ran out, “they began to use their spears against each other, and the battle had come still more to close quarters.”42 The Roman left soon found themselves under severe pressure, for their opponents were not Persians; instead, they were up against the Kadishaye, a warlike tribe from Beth Arabaye,43 a region some 100 kilometers south of the Dara-Nisibis area. This early Persian advance, however, was exactly what Pharas the Herule had apparently been counting on, for his men “got in the rear of the enemy and made a wonderful display of valorous deeds,” according to Procopius.44 The leftward Hun unit also joined in the fray, and the Kadishaye found themselves surrounded and slaughtered. Three thousand died and the remainder fled to the safety of the Persian infantry lines.

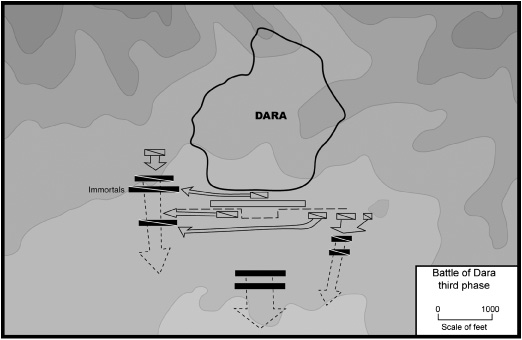

In the meantime, Peroz had been shifting his Immortals out of reserve and to his left. Belisarius saw this and ordered the Huns under Sunicas and Aigan to cease their action on the left and rush to the opposite side of the battlefield. They joined with the right-hand Hun force under Simmas and Ascan. As his initial attack was being driven back, Peroz ordered his left-flank cavalry forward with the Immortals in support. As did the other assault, this too gained some early success and forced the Roman cavalry back. Focused on the retreating cavalry, the Sassanids were unprepared for the Huns to strike their flank. The Hunnic cavalry drove not only into but through the charging Sassanids, separating them into two forces. At this point the retreating Romans stopped before the rapidly rising ground and turned to meet their attackers, now weaker by half.

The combat turned into melee, made more chaotic as Belisarius and Hermogenes lent the weight of their reserve cavalry. Sunicas killed both the Immortals’ standard bearer and their commander, Barasamas. “As a result of this the barbarians were seized with great fear and thought no longer of resistance, but fled in utter confusion,” Procopius writes. “And the Romans, having made a circle as it were around them, killed about five thousand.”45 Struck from multiple angles and leaderless, the Sassanid cavalry broke. With the cavalry streaming to the rear, the infantry also broke and ran. The pursuit was on, but Belisarius halted it rather than attempt an annihilation. He knew that a cornered army could fight desperately and snatch victory from defeat, a prospect he was not willing to face. Instead, Belisarius was content to win a clear-cut victory and enjoy the benefits to his troops’ morale.

All the battles discussed to this point have been won by the offense, but at Dara the defense prevailed. Belisarius had used the time during the peace talks not only to gather forces but also to prepare his position. The extended ditch across his front discouraged a frontal attack, encouraging Peroz to split his force and attack the flanks with fewer troops. Since the Persians had twice as many men, the division of forces apparently did not affect Peroz as it should have. The trench provided an artificial obstacle by which Belisarius was able to channel the Sassanian avenues of attack; it also provided security for his lesser-quality infantry and disrupted any plan for a massed assault. Belisarius’s uses of mass and concentration were most notable; he quickly moved his central Hunnic horse to either flank as necessary to counter the Sassanian cavalry charges. His one use of concealment and cover, the Herules behind the hill on his far left flank, also proved effective. Being on slightly higher ground than the attackers, Belisarius also had the advantage in observation; his sighting of the Immortals shifting into position for the attack gave him time to shift his own Hun cavalry completely across the battlefield while preparing his personal bucellari reserve for the final counterattack. The positioning of his force so close to the city gates, as well as the rapidly rising ground behind his forces and the city, kept his line of communication secure and severely restricted any chance of the Sassanian cavalry succeeding in a flanking attack or move to the rear.

The loss of as much as half his army shocked Peroz and Cavadh. To make matters worse, a subsidiary offensive to the north was also defeated. Temporarily, at least, the Romans had the upper hand in this section of the frontier. After several months, Cavadh took the advice of an Arab ally named Almondar, as Mahon describes, to “avoid the beaten track of Amida or Nisibis, and to invade the Roman territories for the first time on the side of Syria. Here his approach would be unexpected, and therefore his progress easy, and he might hope to reduce the city of Antioch, which its luxury rendered both alluring and defenseless.”46 Early in 531 Cavadh sent 15,000 cavalry on a sweep to the west, the force being commanded by Azarethes. When they reached Gabbula, some 100 miles south of Antioch, the alarm was raised. Belisarius reacted swiftly by leading 20,000 men to cut off the Sassanian approach. His army included 2,000 local recruits and a number of less-than-experienced forces, for he had been obliged to leave veterans behind to guard the frontier posts if this attack proved to be a diversion for a larger Sassanian attack elsewhere.

As soon as Azarethes learned of Belisarius’s approach, he began a withdrawal. Belisarius shadowed them a day’s march behind. He viewed an expulsion of the enemy without a battle to be better than the risk of combat with his potentially untrustworthy troops. According to Procopius, however, Belisarius allowed himself to be swayed by aggressive subordinates and the urging of the army as a whole. After he addressed them on the folly of fighting in the wake of an extended Easter fast, the troops “began to insult him, not in silence nor with any concealment, but they came shouting into his presence, and called him weak and a destroyer of their zeal; and even some of the officers joined with the soldiers in this offence, thus displaying the extent of their daring.”47 Belisarius eventually gave in to their demands and deployed along the right bank of the Euphrates, opposite the town of Callinicum.

Procopius describes the battle as hard and closely fought, with much damage inflicted on both armies by archers. Then, late in the day a Persian attack on the allied Saracen cavalry broke through the Roman right flank, cutting off a Roman retreat. Belisarius led the infantry as long as he could, but as the Persians made more progress on both flanks he finally led the remnants of his men into and across the river to safety. John Malalas, however, gives a different account. He claims that as the right flank collapsed and many of the new recruits “saw the Saracens fleeing, they threw themselves into the Euphrates thinking they could get across. When Belisarios [sic] saw what was happening, he took his standard with him and got into a boat; he crossed the Euphrates and came to Kallinikon. The army followed him. Some used boats, others tried to swim with their horses, and they filled the river with corpses.”48 Malalas asserts that two subordinates led the fight to cover the escaping army, and they held the Persians at bay until dark.

Wherever the truth lay, the battle was a Roman defeat. However, it had little major consequence in the overall scheme of things, for Cavadh soon died and his heir, Chosroes, took the throne and initiated peace talks. Zachariah of Mitylene reports that “Belisarius, being held culpable by the king on account of the rout which had been inflicted on the Roman army by the Persians at Thannuris and on the Euphrates, had been dismissed from his command and went up to the king.”49 He was recalled to Constantinople, either as punishment for his defeat or in preparation for the invasion of Vandal-held North Africa (depending on which author one believes). The battle did, however, prove to be Belisarius’s last defeat.

In Constantinople, Belisarius ingratiated (or reingratiated) himself with Justinian by suppressing a major domestic revolt, the Nika riots, in 532. The following year he led an expedition to Carthage to challenge Vandal dominance and begin Justinian’s master plan to establish his rule in as much of the old Roman Empire as possible. Two major battles, Ad Decimum and Tricameron, were both Roman victories with cavalry; infantry were nearby for the battles but not directly involved in them. Neither will be discussed here, for they were as much Vandal defeats owing to their King Gelimer’s poor leadership as they were Belisarius’s victories won through persistence and hard fighting. They certainly aided in reinvigorating his reputation, although this wasn’t necessarily a blessing. While Belisarius gained the confidence of his men by winning a campaign far from home with a smaller army than the one he faced, he also came to the attention of Justinian, who knew the fate of emperors with too-successful generals: they often found themselves overthrown. From this point forward, Justinian gave Belisarius more and more difficult tasks but with smaller and smaller forces. It is to Belisarius’s credit that he not only succeeded in making bricks with very little straw but he also never let his emperor’s paranoia become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

THE BYZANTINES HAD FOR SOME TIME been on good terms with the Ostrogoths, branch of the Eastern Germanic Goths located in Italy. The eastern empire had supported the Gothic king Theodoric when he invaded Italy to defeat Odovacer in 493. Once established in Ravenna, Theodoric ruled not only as king of the Ostrogoths but as the eastern emperor’s viceroy. A minority population in Italy, the Goths worked successfully with the existing Roman bureaucracy. Theodoric maintained a clear distinction between his own people and his Roman subjects, but he hoped that the Ostrogoths could elevate themselves to a level with the people they ruled.50 The “viceroyalty” extended throughout Italy and into Pannonia.

All was well as long as Theodoric lived. Unfortunately, the successors of a great king rarely match his talents. Theodoric left behind but one child, a daughter named Amalasuntha. Her first husband died, leaving behind a son, Athalaric. Amalasuntha seems to have been quite capable in her own right and served as regent to her young son, but Gothic tradition would not allow a queen to be supreme ruler. Early in Justinian’s reign, he had sought to strengthen relations with Theodoric, but soon he began to persecute Christian heresies, which included the Arianism practiced by the Goths. When Theodoric died in 526, the combination of religious persecution and the question of royal succession disturbed the Gothic population. Amalasuntha sought cordial relations with Justinian and aided him in his war against the North African Vandals by allowing free use of Sicilian bases. Her regency ended, however, when Athalaric died. Amalasuntha offered to marry Vandal chieftain Theodahad on the presumption that she would remain the power behind the throne. He agreed to the marriage, but afterward subverted her authority and within a few months had her killed (April 535). Justinian used the murder as his justification for committing troops to Italy. Theodahad could step down as king and swear fealty to Justinian, but anything less than that meant war.

THE OSTROGOTHS AND VISIGOTHS THAT FOUGHT together and defeated the eastern Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 376 apparently were so satisfied with their weapons and tactics that very little had changed by the time Belisarius invaded Italy. The cavalry made up the bulk of the army and could be classified as heavy. A Gothic horseman wore a helmet with protection for his neck and cheeks and a flexible suit of armor, of metal or leather, which reached down at least to his knees. He wielded the extralong thrusting lance, the contus, to which a pennant was affixed, and he carried a sword and small shield as secondary weapons for close combat on horseback or when dismounted. The warriors rode armored horses and charged at the gallop with long lances held in close formation.51

Theodoric had begun expanding the role of infantry, but it still remained very minor. What archers the Ostrogoths used were infantry. They had greater range with their bows than did mounted archers, but were not as strong on the defensive as heavy infantry. Although the cavalry did depend on them as a line behind which to retreat, it was for the shield of arrows rather than the physically solid defense heavy infantry could provide.

Little had changed in the nature of Gothic tactics, attitudes, or armament since the days of their first appearance in Europe, nor had the basic technological aspects of warfare changed.52 The Ostrogoths used swords produced in Roman shops or with very similar techniques.53 Exposure to the Romans had altered their order of battle structure, however, primarily during Theodoric’s reign. The Ostrogoths achieved a reputation of strength against other barbarians by building on their own traditions, but they also adapted some Roman organizational and support systems.54 Their tactics relied primarily on mass, with only basic maneuvers included. The principal elements of Gothic tactics were lightning-quick attacks launched from ambush and accompanied by loud war cries, outflanking maneuvers to attack the enemy’s infantry, the hard and fast cavalry charge in the hope of dealing a decisive blow before the horses were exhausted, quick retreat behind the lines of their infantry in case the attack failed, and gathering new forces for follow-up attack, reinforced by reserves.55 Unfortunately for the Goths, ambushes were difficult to set up during a siege. Therefore, they had to depend on infantry (their secondary arm) for scaling walls, for which they had little skill or experience, or await a Byzantine sally in order to bring their cavalry into play.

JUSTINIAN SENT BELISARIUS TO SICILY in 536 with some 4,000 Byzantine soldiers and foederati, 3,000 Isaurians, 200 Huns, and 300 Moors, as well as Belisarius’s bucellarii in unknown numbers. While this is a small force with which to capture all of Italy, Justinian did send a force to threaten the Goths’ northern border: Mundas, commanding Byzantine forces in Illyricum (along the eastern Adriatic coast), was ordered to invade Dalmatia.

Those two forces in conjunction with an alliance with the Franks in Gaul gave the Goths three threats to face. While those were sufficient to strike fear in the Gothic king’s heart, Belisarius’s quick capture of Sicily sent him into a panic. Gibbon writes that although Theodahad “descended from a race of heroes, he was ignorant of the art, and averse to the dangers, of war.”56 He quickly entered into negotiations with Justinian’s envoy, signing a treaty that would make Italy subservient to the empire in return for his retention of the throne. A second treaty, to be offered if the first was rejected, was to retire from the throne in return for a sizable pension. Justinian rejected the first, demanding abdication; he gladly agreed to the second. Theodahad, however, refused to abdicate upon learning that the Byzantine force approaching through Dalmatia had been defeated. He should have taken the money and run. Instead, he bribed the Franks sufficiently to keep them at bay and now had only one army to face.

By the spring of 536 Belisarius had not only conquered Sicily but had made a quick punitive expedition to Carthage as well. Leaving a small garrison in Palermo, he crossed the strait of Messina into the toe of Italy and began his march northward. His first challenge came at Naples. The citizens negotiated with Belisarius; unfortunately, they could not decide with which power their security lay, the Goths or Romans. The Goths had ruled fairly for decades and done little to restrict the habits of the Italians. The Byzantines, on the other hand, were painted by the Goths to be more Greek than Roman and with no real interest in taking care of the citizenry. The Neapolitans suggested Belisarius just move on toward Rome, but he could not leave a major city and Gothic garrison behind him. A twenty-day siege ensued that cost Belisarius men as well as time, but finally a secret entrance into the city was discovered and Naples fell. Only after significant pillage, looting, and rapine did Belisarius restrain his troops. Leaving another garrison behind depleted his forces even further, and he marched for Rome with perhaps 5,000 soldiers.

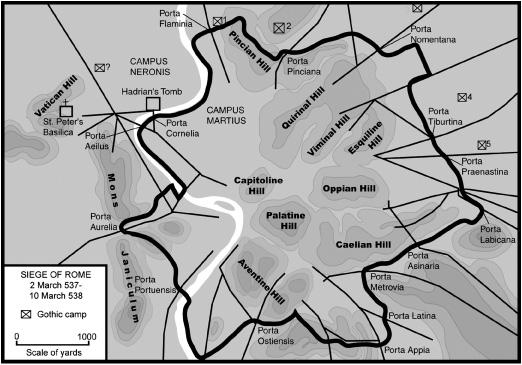

With Naples lost and a renewed Byzantine offensive in Dalmatia, Theodahad ran. The Goths had had too much of his self-serving dithering. In November 536 a gathering of Gothic warriors declared Theodahad dethroned and, as there were no more male members of the royal family, elected a man of obscure birth but of some military experience named Vittigis. In retrospect, the choice could have been better, but he was an improvement over Theodahad, who was captured and executed.57 In Rome, Vittigis made a smart political move rather than a smart military one. He left a 4,000-man garrison in Rome and marched the rest of his army to the capital at Ravenna, where he forced Theodoric’s granddaughter Matasuntha into marriage, thus giving his kingship some measure of legitimacy. Meanwhile, Rome was changing hands. Fearing a repeat of the Neapolitan experience, the citizens of the Eternal City opened their gates to Belisarius on 9 December 536. Without local support, the Gothic garrison fled.

However, the Roman citizens were not too enthused about facing a siege by their erstwhile overseers. As Lord Mahon describes, “With all the eloquence of cowardice, they attempted to dissuade Belisarius from his project of fortifying Rome, and represented, in glowing colors, the inadequate store of provisions for its maintenance, and the vast and untenable extent of its walls. They urged that its inland position cut off all maritime supplies, and that its level site presented no natural advantage for defense.”58 Belisarius politely took note, but restored the walls, emptied ships from Sicily of their grain, obliged the locals to bring him the harvest, and sent out troops. Some spread around the southern and eastern countryside, gathering in more supplies from cities the Goths had left either lightly garrisoned or undefended. He also sent forces northward to seize key fortresses, hoping to delay Vittigis’s advance.

Vittigis was soon on his way. With his forces making little headway against the Byzantines in Dalmatia, he decided to attack Rome. News of the size of Belisarius’s army encouraged him and he sped for the city. The troops Belisarius had sent north either fled back to Rome or closed themselves up in the fortresses they had captured, there to be isolated by small Gothic forces. Procopius numbers the Gothic army at 150,000, but modern historians disagree.59 Fifteen thousand seems the more likely number, though Ernest Dupuy and Trevor Dupuy propose 50,000.60 Suffice it to say, Belisarius was outnumbered. The Gothic numbers must have been relatively low, however, for they only besieged the northern half of the city.

By seizing the towns of Spolento, Narni, and Perugia, Belisairus did oblige Vittigis to slow his rush for Rome. Belisarius put the time to good use, not only strengthening the walls but digging a wide trench outside them. He also built a tower to guard a bridge the Goths would be crossing. Generally described as the Milivian Bridge, it may have been another bridge across the Anio River, today known as the Teverone, and Procopius describes both that river and the Tiber by the same name. The fort was certainly stout enough to defend the bridge, but the fortitude of the defenders was not. They fled rather than fight, and a few more days of preparation were lost.

Combat occurred quickly. Apparently in ignorance of the fall of his bridge fort, Belisarius led 1,000 cavalry out on a reconnaissance mission. They were surprised by a large Gothic force and obliged to stage a fighting withdrawal. One of the fort’s deserters identified Belisarius to the Goths as riding a distinctively white-faced horse. That meant the bulk of the Gothic army aimed toward the Roman commander in order to reap immense glory. Belisarius and his bodyguard had an intense melee on their hands, and they retreated back to the gate—only to find it closed against them. Rumor had spread inside the walls that Belisarius was dead, and the citizens were not about to let an angry horde of Goths into the city, no matter how many Romans may have been left outside. Faced with an unenviable situation, Belisarius did the unexpected: he ordered a charge. The turnabout was so sudden and violent the Goths assumed a fresh force must have sallied from the gates, so they retreated to their camps in fear. The remaining Romans and their commander (not only alive but completely unharmed) then beat their own retreat into the city.

Vittigis sent a representative to vocally harass the citizens of Rome for their betrayal and then ordered the siege to begin. The Goths established six camps, positioned to cover at least one gate each, stretching from the east bank of the Tiber at the Porta Flaminia around to the easternmost gates of Tiburtina and Praenastina. Later, one was set up west of the Tiber on the Plains of Nero (Campus Neronis) near Vatican Hill. Procopius writes that “the Goths dug deep trenches about all their camps, and heaped up the earth, which they took out from them, on the inner side of the trenches, making this bank exceedingly high, and they planted great numbers of sharp stakes on the top, thus making all their camps in no way inferior to fortified strongholds.”61

Vittigis also ordered that the aqueducts supplying the city be destroyed. The besieged were still able to to draw water from the Tiber and from wells, so water was never in short supply, but the flow from the aqueducts had powered the mills. The Tiber therefore became the site for new mills and the grinding continued as long as there was grain. Belisarius had already stationed men at each gate and now drafted townsmen into the ranks to spread his forces a bit farther and give the Romans a stake in their own defense. He also ordered the commanders at each gate to disregard any report of breakthroughs in other parts of the city; they should continue to man their posts and not fly to aid others, since such alerts may have been nothing but rumors.

Learning from deserters of discontent within the city, Vittigis sent envoys to offer the Byzantines safe passage out of Rome. Belisarius was brusque (and prescient) in his reply: “I say to you that there will come a time when you will want to hide your heads under the thistles but will find no shelter anywhere.… And whoever of you has hopes of setting foot in Rome without a fight is mistaken in his judgment. For as long as Belisarius lives, it is impossible for him to relinquish this city.”62 Vittigis, however, was determined to make short work of the siege and began building assault engines. Three weeks into the siege, the assault weapons, wheeled towers protecting battering rams, were built and ready for use. Vittigis also had large numbers of scaling ladders built and fascines bundled to fill in the ditch outside the walls.

Belisarius had also been using his time placing his own engines for defense. Along the walls were placed a number of ballistae, catapults firing bolts shorter but thicker than arrows to a range roughly twice that of a bow. Inside and protected by the walls were onagers, consisting of an arm affixed at the bottom by braided rope that built torsion as the arm was pulled backward and downward; the opposite end of the arm comprised a sling holding a rock. When the arm was released the rock soared high and far. (The trebuchet of later centuries used a pivot and counterweight to accomplish the same action.) The accuracy of the onager was minimal, but the ballista could and did wreak great havoc.

Vittigis brought his engines forward on 21 March. Many of the defenders (mainly the civilians) were fearful, but Belisarius laughed. Many thought it was bravado, but he soon showed them the cause of his humor. Ordering the archers to hold their fire until he gave the signal, Belisarius allowed the rams to be hauled by their ox teams into arrow range. He then nocked an arrow and shot it through the throat of one of the Goth officers. Another followed with identical results. At that, masses of arrows flew into the advancing army. Belisarius had the archers closest to him concentrate their fire on the oxen, which soon left the rams immobile far from the city walls.

Vittigis left a force of archers behind with orders to keep up a steady fire on the defenders while he led an attack on the city gate called the Porta Praenestina to the east. Meanwhile, a third force attacked across the Plain of Nero to Hadrian’s Tomb. The walls there seemed so formidable that Belisarius had stationed only a small force guarding the tomb and the Porta Cornelia. The Goths rushed the walls with large shields protecting them from arrows and were soon at the walls with scaling ladders. The defenders could not shoot down on the advancing Goths without exposing themselves, so found themselves in dire straits. One soldier, looking about, noticed the large number of marble statues around the tomb. He began breaking them into pieces and hurling the marble blocks onto the attackers. Soon all the defenders were pelting the Goths, who were forced away from the walls and then became exposed to arrow fire. Thus, the handful of defenders repelled the assault. Belisarius ordered sallies from various gates to attack the Goths while they were spread out; they abandoned their assaults and fled back to their camps. “Then Belisarius gave the order to burn the enemy’s engines, and the flames, rising to a great height, naturally increased the consternation of the fugitives,” Procopius writes.63

“Such was the loss and consternation of the Goths that, from this day, the siege of Rome degenerated into a tedious and indolent blockade,” writes Gibbon.64 At this point Belisarius wrote to Justinian, begging for reinforcement. While detailing his successes, he subtly applied some pressure on the emperor to act if he wished their victory to continue. He reminded Justinian that “it has never been possible even for many times ten thousand men to guard Rome for any considerable length of time…. And although at the present time the Romans are well disposed toward us, yet when their troubles are prolonged, they will probably not hesitate to choose the course which is better for their own interests.… [N]o man will ever be able to remove me from this city while I live; but I beg thee to consider what kind of a fame such an end of Belisarius would bring thee.”65 Upon receiving this letter, Justinian responded, but the reinforcements he sent were obliged by bad weather to stop and winter in Greece.

At this point Belisarius sent nonessential personnel out of Rome to Naples, something he probably should have done earlier in order to stretch his supplies. Luckily, they were not attacked as they fled south. He also kept supplementing the food supply by sending out his Moorish soldiers at night, when the Goths did nothing but post guards at their camps. The Moors gathered supplies and ambushed the occasional Goth soldier or patrol. This served not only to supplement the food supply, but to bolster Roman morale while harming that of the Goths. In response, Vittigis sent a large force to capture the city and harbor at Portus, which denied the besieged any succor by ship. Belisarius knew the loss of the harbor would be important, but he simply did not have the manpower to spare in order to protect it. The nearest port available to Belisarius was now Antium, a day’s travel to the south. It was from there that, three weeks after the Goths captured Portus, he received a reinforcement of 1,600 cavalry dispatched from Constantinople before the siege began.

With the extra manpower now available, Belisarius was not about to let his men stand idle. He sent cavalry units out to nearby hills. When the Goths massed to charge them, the Byzantine arrows caused great damage while the attackers were at some distance. Procopius writes that “since their shafts fell among a dense throng, they were for the most part successful in hitting a man or a horse.” When the cavalry had expended their arrows, they rode for the city gates with the Goths in pursuit. “But when they came near the fortifications, the operators of the engines began to shoot arrows from them, and the barbarians became terrified and abandoned the pursuit.”66 All of this encouraged the citizenry to get in on the action. They begged Belisarius to let them participate in battle. Procopius tells how Belisarius finally relented to their entreaties, as he had done against his better judgment at Callinicum against the Persians. The disaster was much the same. After early success with his cavalry, Belisarius allowed a phalanx of civilians to sweep the outnumbered Goths from their position on the Plain of Nero. Unfortunately, the loot of the camp became more interesting than the pursuit of a defeated enemy; the Goths re-formed and recaptured their camp. The untrained civilians dropped everything and fled for the city, only to find the gates closed to them and the hotly pursuing Goths. Belisarius and the cavalry saved the day, but the battle could be called nothing better than a draw.

In midsummer an envoy arrived from Constantinople with a large sum of money to pay the troops. Belisarius launched a diversionary attack out of two northern gates while a bodyguard escorted the money into the city from the south. That raised morale temporarily, but soon the citizens were once again complaining; the best Belisarius could do was promise (and hope) that reinforcements were on their way. In the fall he sent Procopius to Naples to recruit more soldiers, then sent his wife, Antonina (who had traveled with him on this campaign), to use her organizational abilities to work on supplying ships and food. Meanwhile, he gambled that the Goths would be feeling the pressure of short rations as well. Belisarius sent raiding parties into the countryside to attack Gothic supply trains and threaten towns along the lines of communication. By intercepting enemy supplies he would not only alleviate the situation in Rome, “the barbarians might seem to be besieged rather than to be themselves besieging the Romans.”67

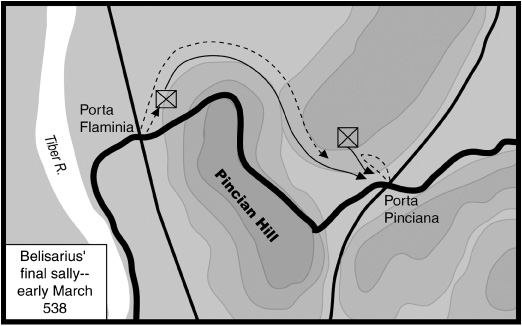

Indeed, the promised reinforcements did arrive: 3,000 Isaurians, 800 Thracians, and 1,000 Byzantine cavalry, plus 500 soldiers Procopius had recruited or relieved from garrison duty. Antonina had gathered a fleet of ships and a large store of grain. The supplies and cavalry started for Rome, with the ships intending to land at the port of Ostia, across the Tiber from the harbor at Pontus that the Goths had captured. It was now late February or early March 538. Learning that both men and supplies were approaching, Belisarius planned one more major diversion. Throughout the siege the Porta Flaminia had been walled up with stone; Belisarius had done this to make the gate assault-proof from the Goths’ camp just outside. During one night in March, he had the stones quietly removed until the gate was passable. The next morning he ordered a thousand men to sally from the Porta Pinciana, the next gate to the east from the Porta Flaminia. They were ordered to charge the nearest Gothic camp, then “flee” when counterattacked. This they did. As the Goths were in hot pursuit, Belisairus ordered another force to burst through the Porta Flaminia and strike the pursuing Goths in the rear. The Goth’s ensuing confusion was compounded by the Romans turning from their flight and attacking, as well as the addition of fresh troops from just inside the Porta Pinciana. The few Goths who survived fled to their camps and feared to emerge.

This brought the defense of Rome to a successful end. Vittigis offered a three-month truce, which allowed free passage of food and reinforcements into the city. Belisarius also sent more forays into the countryside to harass the Goths. Ultimately Vittigis abandoned the siege and fled for Ravenna.

Although Belisarius was the greatest field commander of his day, most at home in the open pitched battle, of which he was the master, the siege of Rome proved he was hardly one-dimensional and may have been the highlight of his career.68 Indeed, Belisarius seemed to do everything right. He spent the three months prior to the Goths’ arrival repairing the city walls and placing his engines of war. The Goths, by encamping only on one side of the city, allowed Belisarius to maintain the bulk of his forces in one area. His use of local citizenry intermixed with his troops gave increased security by expanding his numbers while still allowing the soldiers to keep a close eye on the civilians. Thus, while there were deserters, there was no serious attempt by the locals to collaborate with the besiegers. Further security was maintained later in the siege by Belisarius’s decision to have the Moors patrol outside the walls at night, both scavenging and ambushing unwary Goths.

The strongest aspect of the defense was its activity. Belisarius carried the fight to the Goths more often than they attacked the city. This use of attack and feigned retreat worked over and over. Only the attack using the Roman civilians was not a success, When attacked, Belisarius was able to shift men to various portions of the wall when hard-pressed, and by holding that redeployment authority solely in his own hands he maintained unity of command. Finally, Belisarius’s flexibility showed constantly, as he used raiding parties against Gothic supply lines and lured attacking Gothic forces into ambushes either by secondary sallies or by luring them into range of the defenders’ fire from the walls.

ECONOMY OF FORCE WAS EASILY BELISARIUS’S greatest strength, primarily because it was forced upon him by his parsimonious and suspicious emperor. He was outnumbered in every battle he fought, and as his career progressed he was given fewer and fewer men to accomplish his missions. (He commanded 25,000 at Dara, 15,000 against the Vandals in North Africa, and 7,500 in his invasion of Italy.) In the Battle of Dara he placed sufficient forces on either flank for defense, but used his mobile Hunnic cavalry in the center as the deciding factor on both flanks. At Rome, he focused his manpower at the gates and spread his force along the walls only when under attack. His infantry archers could man the walls while his cavalry could launch raids outside. In the greatest show of this principle, Belisarius intentionally depleted his defending force in order to send multiple columns into the countryside to disrupt the Gothic supply lines. He thus focused enemy attention away from the city and depleted their food supply while supplementing his own. His deployment of small cavalry forces to hilltops to draw Gothic attacks into missile fire always inflicted many more casualties than he suffered. His only violation of this principle came when he included the citizenry in an attack outside the city. Although the day was a setback, it could have been disaster.

The best example of Belisarius’s mastery of unity of command came early in the siege of Rome, when a false report spread through the city of an enemy break-in. Belisarius responded by ordering each contingent to man its designated area and ignore any such report. He made sure that his subordinates knew that the moving of reserves from point to point was his responsibility, not theirs. All the planning for offense and defense came from him. At Dara he was technically a cocommander, but since Procopius mentions Hermogenes only in passing we can assume that Belisarius, though the younger man, was in command and that the deployment and movement of forces was in his control. He did show his ability to take suggestions, however, when he agreed with the Herulian commander’s idea of hiding his force behind a hill in order to take advantage of the cover for an attack on the Persian cavalry’s rear.

Unfortunately, Belisarius failed to exercise this principle in his two defeats. At Calliculum and in the major attack at Rome, Procopius tells us that Belisarius submitted against his better judgment to entreaties from his soldiers at the former and the civilians at the latter. While open-mindedness is certainly a virtue, a leader has to know his mission and give orders that fulfill it, no matter what his men or subordinates may think. Chasing the Persians out of Byzantine territory was his mission, and at Callinicum there was no need to engage an enemy that was voluntarily disengaging through a strategic withdrawal. At Rome, Belisarius’s mission was to use minimal manpower to defend the huge stretch of Rome’s city walls, and an assault with a large and untrained force of locals could have little advantage other than for morale purposes. In both cases Belisarius forsook unity of command and risked major disaster.

The principle of maneuver was undoubtedly one of Belisarius’s strengths. It is a tribute to his ability to maneuver that in both the battles discussed (as well as his first victory in North Africa), he won against attacking armies. At Dara, his use of cavalry created ambushes against superior forces on both flanks. At Rome, he displayed more ability to maneuver on the defense than did Vittigis on the offense. He consistently placed the Goths at a disadvantage by forcing them into no-win situations. During the main Goth assault on the walls, he not only shifted manpower as necessary within the city to meet attacks from various points but also followed up the Gothic assault with one of his own to chase the retreating enemy and destroy their siege engines. These actions always took place from the gates facing the enemy, for quick striking and quick withdrawal. Belisarius’s deployment of relatively small cavalry forces on hilltops to draw Gothic cavalry into long-range arrow fire worked every time he tried it.

Using the unguarded gates, his dispatch of night patrols not only strengthened security but also brought in much-needed food and obliged the Goths to stay in their camps. Strategically, his dispatch of cavalry forces to harass the enemy supply line and attack enemy towns created far more discomfort for the besiegers than for the besieged. Basil Liddell Hart writes, “Though the strain on the defenders was severe, the strength of the besiegers was shrinking much faster, especially through sickness. Belisarius boldly took the risk of sending two detachments from his slender force to seize by surprise the towns of Tivoli and Terracina, which dominated the roads by which the besiegers received their supplies.”69 Even in the one major mistake of the siege, his attack with the civilian infantry, Belisarius’s quick action with his cavalry saved the bulk of the citizens by covering their retreat into the city.

Liddell Hart describes Belisarius as being a master of the defensive-offensive strategy. “Belisarius had developed a new-style tactical instrument with which he knew that he might count on beating much superior numbers, provided that he could induce his opponents to attack him under conditions that suited his tactics. For that purpose his lack of numbers, when not too marked, was an asset, especially when coupled with an audaciously direct strategic offensive.”70 Thus, Belisarius would advance strategically to a point where he would provoke an enemy response, and then on the battlefield would stand on the defensive until his enemy made a mistake or retreated, upon which he would turn to the offensive. Centuries later, Clausewitz would restate this very principle: “Once the defender has gained an important advantage, defense as such has done its work.… A sudden powerful transition to the offensive—the flashing of the sword of vengeance—is the greatest moment of the defense.”71

Belisarius knew the strengths and weaknesses of his troops and their weaponry, and maximized what he had to take advantage of his opponents’ weaknesses. This is best shown at Rome, where his horse archers repeatedly bested the Gothic heavy cavalry armed only with lances and swords. They could, however, fight toe-to-toe if necessary, as they did at the beginning of the siege at the abandoned river fort. His personal leadership in the midst of combat was a major influence in maintaining morale. His actions were always well planned; he always spent as much time as possible gauging the situation before committing his men to action.

Belisarius also developed into a master of deception. As his career progressed, deceptive operations became increasingly important in his plans. Capitalizing on his trenchworks at Dara and thereby obliging the Persians to divide their cavalry, as he wanted them to, showed great talent for a young commander, but also the ability to learn from his enemies. He also was able to consistently lure the Goths into ambushes outside the Roman walls with feints in one area that opened another area for a lightning attack. Belisarius’s practice of the art of deception reflects his imagination and intellect.72

After the siege of Rome was lifted, Belisarius swept up the Italian Peninsula all the way to Ravenna, aided with more reinforcements led by Justinian’s other favorite, Narses. He accepted the Gothic surrender in 540 and was then transferred back to Persia to deal with the breaking of the “Everlasting Peace” that had been signed after his last campaign there. In 544 he was back in Italy suppressing a Gothic uprising. He was besieging Ravenna when the Goths offered the throne of Italy to him, rather than to the Byzantine Empire. Belisarius played along with the offer until he was inside the city; then he took it captive and signed the surrender in the name of Justinian and the empire. The mere offer, however, was enough to spark Justinian’s paranoia, and Belisarius was recalled to Constantinople in 548. After some time in disgrace and forced retirement, he was the only one the emperor could call on when the capital city was threatened by a force of Huns in 559. Now in what would be considered old age, he led a few hundred men against a force of 8,000 and won a miraculous victory.

Like many generals, Belisarius was at times lucky when it came to the ability (or lack thereof) of his opposing commander. Still, given his long string of victories with minimal forces, it is difficult to find fault with his generalship: how many leaders could make such a virtue of necessity, fashioning tactics to suit his smaller armies in order to inflict such a long string of defeats on such a wide variety of opposing generals and armies with superior numbers?