King of Sweden

While the world stands, our king, captaine, and master cannot be enough praised.

—Robert Monro

GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS’S GRANDFATHER, Gustavus I Vasa, is regarded as the “Father of Sweden.” He expelled Danish invaders from the country and was named king in 1523. Gustavus continued to fight the Danes, as well as the Russians, but on the domestic front he is most important for introducing the Lutheran Church. He ruled until 1560, when he was succeeded by his son Erik. Erik’s eight-year reign, marked by increasing insanity, came to an end when he was deposed by his half-brother John. John was king of Sweden and Finland until his death in 1590; during his reign he fought wars with Denmark and Russia. John’s marriage to a Polish princess made it possible to place his son Sigismund on the throne of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1587. Upon John’s death, Sigismund assumed the kingship of Sweden and Finland as well. He ruled from the Polish capital at Krakow with his uncle Charles as regent in Sweden. Sigismund, raised as a Catholic, had agreed not to interfere with Lutheranism in his home country; Poland was a Catholic nation. Thus, it was Sigismund’s support for the Counter-Reformation that motivated Charles to seize control and have the Riksdag (the Swedish legislature) name him king. A Swedish victory over the Poles at the Battle of Stångebro in 1598 led to Sigismund’s official deposition the following year.1

Charles’s son Gustavus thus came to be in line for the Swedish throne only after a tumultuous succession process. Charles ruled with the advice and consent of the Riksdag, and during his reign he consolidated Sweden’s borders and its religion. He taught Gustavus the lessons of ruling well and appointed good tutors for his son’s education. Gustavus’s primary tutors were Johan Skytte (“one of contemporary Sweden’s rather sparse intellectual luminaries”)2 and Johan Bure, an expert in runes and Swedish history and myth. Under the direction of these teachers Gustavus became fluent in five languages and did passably well in five others. His teachers saw a young man grow up with a great appetite for learning, excelling in languages, literature, and science. He became well known for debating nobles and, when his father allowed it, visiting ambassadors and aristocrats. He therefore developed a speaking style that amazed all who came in contact with him; he was regarded as a first-class orator as well as military leader.3 Along with the “book learning,” his father gave him lessons and experience in governing. Charles was often at odds with the Riksdag and could show a strong aggressive streak when opposed. Gustavus learned tenacity from his father, but also learned from observation that in dealing with government, words can sometimes be more effective than actions.

At fifteen Gustavus grew bored with intellectual pursuits and acted the feckless role of a teen-aged prince. He did, however, show a continual interest in military affairs. He had spent much time among military officers and had received a bit of tutelage from Jakob de la Gardie, who had been in the service of the great Dutch general Maurice of Nassau for some years; from Maurice would come Gustavus’s reforms for the Swedish army. Turning sixteen in December 1610, Gustavus felt himself ready for action, and he asked his father for assignment to the east to fight against the Russians. He was denied, but did not have to wait long. In early 1611 the Riksdag declared him to be of age to fight, and the Danes (and their Norwegian subjects) were invading about the same time. The Danish army under King Christian IV captured the city of Kalmar on Sweden’s southeastern coast and raided across the countryside, capturing some towns and destroying others. In April 1611, Gustavus was knighted and sent to collect troops to fight for the relief of Kalmar. He quickly recaptured the isle of Öeland, directly opposite Kalmar. He also was successful in the destruction of the town of Christianopol (modern Kristianstad) by outfitting his soldiers in his enemy’s traditional clothing—his first use of deception as a combat technique.4 Gustavus launched a surprise night attack and captured the town quickly; he then ordered the population to leave and burned it to the ground. A few other small actions met with success but in the fall of 1611 Charles, who had been in deteriorating health for some time, finally died. At only sixteen, Gustavus now found himself king and commander in chief.

With two fortress cities in Danish hands, Gustavus broke with contemporary strategic thinking and did not lay siege to either. Instead, he launched an attack into Danish-held territory to the west. It failed, but he launched another, hoping to draw the Danes out of the cities and into the open. They would not comply, however, but instead prepared a naval assault on Stockholm. When Gustavus learned of this, he force-marched his 1,200-man force 240 miles in a week to reach the capital before the attack. There, he put every available man in the city in uniform and awaited the assault. Seeing the large force arrayed against him and not knowing many were civilians, King Christian withdrew. Little more fighting was done and a peace was concluded in 1613. Gustavus negotiated the return of both fortresses, Kalmar and Älvsborg, though he had to buy back the latter. Denmark was out of the way, but Russia and Poland still presented problems.

Gustavus’s cousin and rival, Sigismund of Poland, refused to discuss a peace treaty but did extend an existing truce for another five years.5 Gustav used the time productively. His first move was to address his remaining rival, Russia. At that time Poland ruled much of northwestern Russia, and the Russian nobles were not happy with Sigismund. They offered the throne of Muscovy to Gustavus’s younger brother, Charles Phillip. Gustavus hesitated, however, and the throne went instead to a Romanov. Gustavus apparently believed that trying to control such a vast area was more than Sweden could handle, or more trouble than it was worth. As Nils Ahnlund, one of Gustavus’s primary biographers, notes, “He had not an atom of confidence in the Russians. He considered that he had a very good notion of their national character, and believed that when dealing with them, even under conditions of peace and friendship, it was essential always ‘to keep the possibility in view of having to fight.’ His policy was innocent of illusions.”6

Sweden already held outposts on Russia’s Baltic coast (notably Novgorod), and in 1614 Gustavus launched an invasion from there. The primary action was the siege of Pskov, which Gustavus wisely broke off as the winter approached. Little else happened, and a peace treaty was signed in 1617 that gave Sweden control of the entire Russian Baltic coast, and by extension control of all of Russia’s overseas trade. In this brief campaign, Gustavus made two key military decisions. First, he displayed the importance of armies versus positions. He told his second in command, Jakob de la Gardie (his tutor on the Dutch tactics of Maurice), that Novogorod was not to be held to the last man if besieged. The city was valuable for trade, but not as important as an army of veterans. Second, he imposed the strictest discipline on his troops: there was to be absolutely no pillage and rapine. All supplies were bought and paid for from the locals, and any failure to follow those orders merited a death sentence. Such a reputation would serve Gustavus well in the future. With two enemies now at peace and a third under truce, the young king now began to implement the improvements to his army that would take him to his fame.

SINCE THE MIDDLE OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY, the battlefield had been dominated by the pike. The millennium-long ascendancy of cavalry had begun its rapid decline in the face of long-range firepower in the form of English longbows and gunpowder weapons. While they stopped the charges of the heavy cavalry knights of the Middle Ages, the bowmen and gunners needed protection. Ultimately, the bow fell from widespread use in Europe owing to the difficulty in learning to handle the longbow effectively and the relatively short range and slow reloading of the crossbow. The gunpowder weapon that came to the fore was the arquebus. It also had limited range and a slow reloading time, but it was the easiest to teach recruits how to use. Over time the arquebus evolved into a heavier matchlock musket. Essentially a very large arquebus, a matchlock could weigh as much as twenty pounds. It had a bore of twenty millimeters and fired a two-ounce ball, twice the weight of an arquebus shot. One man could operate this gun by use of a separate, forked rest to support the barrel. Its portability, stopping power, and 400-yard range made it so useful that in spite of its inaccuracy musketeers gradually replaced half the arquebusiers in Spanish infantry units, and most European armies took up the musket.7

That is where the pike came in. Its length kept cavalry at bay while the gunners reloaded. The Swiss had first introduced the massed pike formation reminiscent of the ancient Greek phalanx, but it had been perfected by the Spanish in the form of the tercio. In open terrain, the square of pikemen provided the only place of safety where the infantry gunners might take refuge from the enemy’s heavy cavalry. In turn, the musketeers’ or arquebusiers’ fire could support the pikemen’s defense, and the enemy’s heavy infantry or the attacking heavy cavalry would provide fine targets for arquebus balls.8 The tercio numbered between 1,000 and 3,000 men, depending on the nature of the terrain. The outer ranks wore some armor and were equipped with pikes fourteen feet long. The next ranks inward were unarmored pikemen, and the center was made up of armored men wielding halberds with wooden shafts about six feet long and a metal spearhead with some sort of blade on one side and a hook or spike on the other. Primarily a defensive formation, the tercio also was used on the offense in battles similar to phalanx warfare, pikes against pikes. The tercio took infantry otherwise vulnerable to charges from cavalry and made them a sort of hedgehog, invulnerable and unstoppable. These slow-moving formations would crush anything in their way, unless it was another such massive square, in which case neither side would gain a decisive advantage. The tactics of the period provided no effective means of penetrating this type of defense.9

The muskets were the longer-range offense and defense. In order to maximize the firepower with slow-loading weapons, the Spanish developed the tactic of the countermarch. The gunners would line up in a file ten or twelve men deep. The man at the front of the file would fire his musket, then turn and march to the rear where he would begin the reloading process. The second man in line would follow suit, and so forth until the first gunner was once again at the head of the file, reloaded and ready to fire. The musket was slower to reload even than the arquebus and a musketeer could at best fire a shot every ninety seconds, but the range and hitting power (it was able to pierce plate armor at a hundred yards) made up for it.

When it came to cavalry, the day of the armored knight was gone, and for a time the cavalry reverted to scouting and foraging roles. They began to enjoy something of a resurgence with the development of the wheel-lock pistol, however. The pistol included a steel wheel attached to a spring that the gunner could wind with a wrench and then cock. Then, working on the same principle as a cigarette lighter, when the gunner released the spring, the turning wheel struck flint, sending sparks into the pan, igniting the powder, and thereby firing the gun.10 Although more efficient than the matchlock, it was far more expensive and required a gunsmith to repair the mechanism, whereas a matchlock rarely broke down. For cavalry, however, a matchlock was impossible to use with any degree of effectiveness because it was a two-handed weapon. A wheel-lock could be cocked for later firing and discharged with one hand. A cavalryman would carry two pistols in holsters and a third in a boot and became a force to harass a tercio and potentially cause enough damage to create an opening for charging infantry.

German mercenary cavalrymen developed the tactics to maximize the effectiveness of the wheel-lock pistol. They wore armor for close-in protection, as well as a helmet. They then charged at a trot in a line of small, dense columns, each several ranks deep, and with intervals of about two horses’ width between files. As they approached a tercio, the front-rank horsemen each emptied their three pistols and then swung away sharply to the rear—a tactic called the caracole.11 Thus, the cavalry developed their own version of the countermarch. This took a lot of practice to do well and could be broken up by a countercharge.

This was the way European armies fought for several decades prior to the Thirty Years War. Since the 1560s the Spanish had kept their armies in the United Provinces of Holland, hoping to suppress Protestantism. In an intermittent Eighty Years War, the Dutch learned weapons and tactics from the Spanish, and began to alter them. The architects of this change were Maurice of Nassau and his cousins, William Louis and John. Maurice was not a spectacular general in the field, often too hesitant when haste was called for. Even so, he transformed a motley group of mercenaries and part-time militia into a professional fighting force that was enough to win him a lasting place in the evolution of modern war.12 Although the Dutch operated with a core of native soldiers, they also depended on the mercenaries, who had been the soldiery of Europe for decades. Naval difficulties with the English hurt the income from the New World vital to Spain’s economy and military goals, and irregular pay to their soldiers in northern Europe caused discontent and mutinies. A growing nationalism coupled with a growing navy gave the Dutch both motivation and money to maintain themselves as the war dragged on, and it was those two factors that gave Maurice what he needed to overhaul his army.

Maurice, son of William the Silent, was named at age twenty-one to be an admiral of the Dutch navy and commander of armies opposing the Spanish. The titles did not translate into power, as he was under the authority of a confederation of states that was extremely difficult to make effective. With too many heads of state jockeying for power, Maurice’s noble status gave him influence but not control, so it is even more remarkable that he successfully remade an entire military system while a war was going on. The basis of his reforms came from study of the old Roman and Byzantine military texts, the Renaissance bringing about a fascination with all things from the classical world.

Maurice realized the major problem with the tercio: it was a big target. With artillery still too large to easily maneuver around a battlefield the tercio’s size was a problem, but if employed properly the muskets could provide enough firepower to break a mass of pikemen. Maurice understood that to increase firepower, one would have to bring more guns to bear at once and increase the speed of reloading. Maurice reduced the size of the formations from 2,000 to about 600, made up of companies consisting of 130, and ranged them no more than 10 ranks deep, as opposed to the 25–30 ranks of the tercio. More units meant more guns along a greater front. A more rapid reloading procedure could keep the guns firing faster, and if two or three ranks fired at the same time before retiring to reload, a lot of lead would be flying. In his work on the military revolution of that age, Geoffrey Parker writes, “We can date the Dutch discovery of the ‘volley’ technique very precisely: it first appeared, in diagrammatic form, in a letter from William Louis to his cousin Maurice dated 8 December 1594, and the author asserted he had derived the idea from an assiduous study of the military methods of the ancient Romans.”13 (This is twenty years after Nagashino saw the use of volley fire.) Thinner lines not only created massed firepower but presented a smaller target for return fire.

To further increase firepower Maurice developed iron foundries in the United Provinces to cast cannon, for which he began the standardization of bore and shot, casting only three sizes: 12-, 24-, and 48-pounders, all large artillery pieces and difficult to maneuver. These guns were placed in front of the infantry, who were deployed in a checkerboard formation, as the ancient Romans had been, in order to advance and retreat through the gaps. Cavalry units were placed to protect the flanks. Maurice’s reforms achieved two objectives. First, the battalions were more mobile and better suited to operating in the marshy terrain of the Netherlands. Second, they were much handier than the larger tercios both in offense and defense.14

To make these improvements work, it was necessary to have more than short-term enlistees. The population of the United Provinces was no more than a million people, most of whom were dedicated to farming or trade. Maurice would therefore be obliged to use mercenaries. The difference was that these men were hired for long service, not the seasonal fighting that was typical of the age. Once hired, the soldier now received something almost no mercenary ever had: a regular paycheck and regular supplies. In return for these, he had to undergo intense training, which developed both discipline and unit cohesion. Again, this was something not seen in western Europe since ancient Roman times. Smaller also units meant more units, which meant more officers and noncommissioned officers. These men were usually Dutch rather than foreign, as most of the mercenaries tended to be. Thus, the officer corps had loyalty to the state, and the soldiers developed loyalty to the unit. Pikemen, musketeers, and cavalry working together took constant practice, something no short-timer would have been interested in. The reintroduction of drill into the army was an essential part of Maurice’s reforms and a basic contribution to the modern military system.15

The negative side of the lengthened front was that more men had to actually face the enemy and exercise courage, since there were no longer massed ranks within which a new recruit could be lodged until he had seen some action. This, again, is where the discipline created by the drill and the unit cohesion came into play. Just how effective such training would be was illustrated in the two battles the Dutch army actually fought under Maurice; they were both victories, but hardly overwhelming ones: Turnhout in 1597 and Neiuwpoort in 1600. These suggest that there were still improvements to be made in order to achieve notable victories, but they laid the foundation on which Gustavus built.16

Gustavus took what Maurice had created and adapted it for Sweden and for a more aggressive style of warfare. From a manpower standpoint, Gustavus used Swedes as officers and soldiers, thus creating a truly national army. Mercenaries were simply too independent to form a standing army. Michael Howard observes, “Armies were in a continual state of deliquescence, melting away from death, wounds, sickness, straggling, and desertion, their movements governed not by strategic calculation but by the search for unplundered territory. It was a period in which warfare seemed to escape from rational control; to cease indeed to be ‘war’ in the sense of politically-motivated use of force by generally recognized authorities, and to degenerate instead into universal, anarchic, and self-perpetuating violence.”17 Instead, Gustavus drew on the conscription system initiated by his grandfather and expanded by his father. One man in ten from a community was liable for military service, and the remainder of the citizens provided the necessary taxation and supplies to maintain them. This offered sufficient manpower to create a strong defense force for a population of a million and a half, but to go campaigning would require more. Thus, Gustavus was obliged to fill his ranks with mercenaries when away from home. They, however, would be forced to learn the Swedish way of war.

The soldiers were organized in squadrons of just over 400 men, almost equally pike and musket. They were deployed with the pikemen in the center and the musketeers equally divided on both flanks, all arrayed six deep. Attached to each squadron was a unit of 96 musketeers for reconnaissance or reserve. Three or four squadrons made up a brigade. The infantry were equipped with improved arms. The musket the Swedes used had, like the Dutch, been produced in a standardized caliber. Already the powder horn, used to carry and measure the gunpowder charge, had been replaced by the single cartridge. A premeasured amount of powder was stored in a wooden vial, with numerous vials carried on a bandoleer around the gunner’s neck. Gustavus improved this further by introducing (or perhaps merely expanding the use of) the paper cartridge, with both powder and musket ball combined in one disposable package. The Swedes also abandoned the matchlock for a “snaplock” (an early flintlock). They were issued in great numbers during the 1620s, and not just to artillery and bodyguards as in other armies. One of the main reasons Gustavus introduced this was the difficulty in Sweden of finding material with which to make the match cord.18

The Swedes not only manufactured a lighter musket, but by removing the need for a rest, the number of movements necessary for reloading decreased and the rate of fire thereby increased. The two-rank volley instituted by the Dutch was also changed to three ranks. When the musketeers had their weapons loaded and had completed the shoulder-to-shoulder rearrangement into three ranks, the front rank knelt, the second rank stooped, and the rear rank stood, then all three ranks simultaneously fired.19 Gustavus also altered the nature of the countermarch, whereby the musketeer marched to the rear of the line to reload and await his turn to fire again. After the front three ranks fired, they would stand fast to reload as the following three ranks stepped forward, hence creating almost a rolling barrage.20

The pike underwent a transformation in the Swedish army as well, shortened from sixteen feet to eleven. The metal point extended from a sheath long enough to keep the pike from being broken or hacked off in close combat. Although the pike remained the sole defense for the musketeers, Gustavus used it for more than keeping the enemy at bay. For him the pike was the battle-winning weapon, a left over from tercio-style warfare. The goal of the musketeers was to break the enemy line in order for the pike-wielding infantry to finish the job.21

Shot, however, was not to be provided only by musketeers. Another of Gustavus’s innovations was light artillery. Cannons had long been standard equipment, but were primarily used in siege warfare (very common at the time) with minimal but increasing use on the battlefield. Their size meant that once set in place, they were extremely difficult to move, hence of mixed effectiveness against moving targets. Prior to Gustavus, artillery was considered to be a technological specialty, usually operated by civilian engineers. The gunners often scorned the requirements of standard military discipline and were scorned by the regular army in return. Gustavus made them military professionals as well.22

Maurice had improved the artillery by standardizing bore and shot, but even his guns were large. Gustavus had his foundries cast cannon in 24-, 12-, and 3-pounder sizes. The smallest gun became mobile, drawn by one horse or (in case of need) three men. At 625 pounds, it could be hauled where needed and set up quickly, and it was easier to adjust and maintain fire on targets. Initially Gustavus used a copper-barreled gun wrapped in mastic-coated rope with a sheath of leather, but by the time of his German campaign metallurgy had so improved that the replacement 4-pounder was solid metal. Improvements in gunpowder helped immensely to standardize pressures in the tube, thus permitting reduction in thickness of the barrel. As with the musketeers, a prepackaged cartridge simplified loading and assured a high rate of fire for the guns. This weapon completely changed the role of artillery on the battlefield.23 Gustavus also introduced grapeshot, firing up to twenty-four smaller balls at once in place of one large cannon ball. The Swedish army could thus produce more, and more concentrated, firepower than any army in Europe. Constant practice increased not only the professionalism but the accuracy of the gunners. With these changes, the Swedes had the finest artillery in Europe, and historians have argued that the modern role of artillery on the battlefield truly began with Gustavus.24

“For all that, it was Gustavus Adolphus’s cavalry that became the true decisive weapon and that most fully bestowed offensive power upon his army.”25 So says Russell Weigley, but different authors have their views of which arm was really key to Swedish victories. The cavalry under Gustavus was primarily made up of Swedes, usually the nobility or the wealthy farmers. Gustavus did not employ them as scouts or in the caracole maneuver, the normal roles for horsemen of their day. He wanted to restore the days when cavalry used their weight and speed for shock power. Hence, although the cavalry were armed with the wheel-lock pistols, their primary weapon was the saber. Each cavalry unit had a musket unit attached, so they could approach the enemy at the same speed, and the musketeers could deliver a massed volley that would disorganize the enemy sufficiently to allow the cavalry to launch their charge. The musketeers would reload during the charge to assist with a second wave or cover a retreat, as necessary. Gustavus also attached 3-pounder guns to his cavalry for the same purpose. As mentioned earlier, the role of gunfire was to open a hole in the enemy formation, and the cavalry would use cold steel to finish the enemy off.26

FIREPOWER, CLOSE COMBAT, and cavalry charge all have their proponents as the key to Gustavus’s improved military system. One thing is sure, however: the alterations came during and as a result of the campaign against Poland in 1621. With Denmark and Russia out of the way, and the Swedish army beginning to adapt its version of the Dutch system, the war against Sigismund was the proving ground for weapons and tactics. Details of the war itself are minimal, but the overwhelming shock of the lance-armed Polish cavalry convinced Gustavus to alter his own tactics. Also during this war, in 1623, Gustavus instituted his first artillery company, which by 1629 had expanded to six companies forming a regiment under the command of Lennart Torstensson. The Swedes conquered Livonia (in modern Estonia) fairly quickly and moved the war into Prussia. There, victories were a bit harder to come by, especially when Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand (who was also Sigismund’s brother-in-law) provided an army to assist in the Polish defense. In a battle at Sztum on 29 June 1629, the Swedes came off second-best in a somewhat inconclusive battle, at which Gustavus was almost captured. The battle did, however, bring about another truce between the two powers, as Sigismund was tired of fighting and Gustavus wanted to enter the war going on in Germany.27 Hence, both sides were open to the offers of mediation from England and, more importantly, France. As Basil Liddell Hart writes, “Gustavus was wanted on a greater stage, and [French Cardinal] Richelieu’s master mind pulled the strings to release him for the new part.”28 The Treaty of Altmark began yet another truce, this one to last for six years; this freed up Gustavus to go to war against the Holy Roman Empire, France’s rival.

The Polish war had turned the Swedish army into a finely tuned machine made up of combat veterans. The soldiers and Gustavus had matured from the experience. Theodore Dodge comments, “Under Gustavus’ careful eye, every branch of the service during these campaigns grew in efficiency. Equipment, arms, rationing, medical attendance, drill and discipline, field-maneuvres, camp and garrison duty, reached a high grade of perfection. … Not only had Gustavus learned to know his generals and men, but these had gauged their king.”29

Gustavus’s rationale for invading German territory is the topic of much debate. He quickly became to the German people the champion of the Protestant cause, even though their princes were slower to embrace his crusade. Although Gustavus certainly made war against the Catholic Holy Roman Empire and sought Protestant princes as allies, his motives certainly could have been political rather than religious. In a speech in 1629, Gustavus remarked:

The Papists are on the Baltic. … [T]heir whole aim is to destroy Swedish commerce, and soon to plant a foot on the southern shore of our Fatherland. Sweden is in danger from the power of the Hapsburg; that is all, but that is enough; that power must be met, swiftly and strongly. The times are bad; the danger is great. It is no time to ask whether the cost will not be far beyond what we can bear. The fight will be for parents, for wife and child, for house and home, for Fatherland and Faith.30

When he landed in the province of Pomerania, Gustavus issued a “press release” that was translated and distributed across Europe. It listed his reasons for invasion: diplomatic insults, imperial aid to Poland during the recent war there, imperial designs on the Baltic region, and oppression of the Germans by the emperor. There was no mention of military goals or of religious motivations. Gustavus’s chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, later averred the invasion was “not so much a matter of religion, but rather of saving the status publicus, wherein religion is also comprehended.”31

Gustavus later began to posit the idea of a Protestant league of sorts, which some have suggested meant that he had imperial designs of his own. His major biographers, Ahnlund and Michael Roberts, agree that there was no divorcing politics from religion. It may have been some, any, or all of these motives. Or, to the cynic, none of them: some think he fought for fighting’s sake.32

When Gustavus and his army of 13,000 arrived near Peenemünde on the Pomeranian coast in July 1630, he had but one ally, the port city of Stralsund. The city had been under siege by imperial forces the previous year, and Gustav had dispatched 5,000–6,000 men under the Scottish mercenary Alexander Leslie to stiffen the resistance. The imperial forces’ goal had been to seize the city and take over the fleet in its harbor to create a naval force strong enough to dominate the Baltic, a project hatched between Sigismund and the Spanish (yet another reason for Gustavus to go to war). The reinforced garrison at Stralsund proved too difficult to overcome, so the attention shifted to another port, Wismar.

Although Gustavus had income from tolls from Prussian and other Baltic ports, he needed other sources of financial support as well as military assistance. In 1631 the French diplomat Cardinal Richelieu (angling to increase French power at the expense of the Holy Roman Empire) entered into an agreement to provide a monthly subsidy. He realized the danger of an overly strong Hapsburg empire and was willing to finance efforts to combat it; local princes under more direct threat were less willing. Only those whom Emperor Ferdinand had dispossessed from their lands came to Gustavus’s aid, and that was little more than moral support.

As for his enemies, Gustavus faced primarily Count Johann Tserclaes Tilly, a professional soldier of great experience, who had started his military service in 1574 at age fifteen. Having seen Protestant forces destroy his home province of Brabant in the Spanish Netherlands, he had a passion for revenge. He served in the wars against the Turks and rose through the ranks. He was named an imperial field marshal in 1605; later that year he accepted the position as commander of the Bavarian military. When Bavaria created the Catholic League in 1609, he became commander of its forces. During the Thirty Years War (starting in 1618), he led armies in Bohemia and Denmark, winning an unbroken series of victories. By the time he came to face Gustavus, however, he was of advancing years and declining abilities. Tilly was an excellent commander and had a grasp of strategy at least as good as Gustavus’s, but was wedded to the tercio style of fighting. He has at times been depicted as over-the-hill, but he was not without some of his old talents.33 Often fighting alongside Count Albrecht von Wallenstein, Tilly became supreme commander when Wallenstein was removed from his position shortly after the Swedish forces arrived. Subordinate to both was Field Marshal Count Gottfried Pappenheim, commander of the imperial cavalry. Still comparatively young, he was almost a caricature of a fiery cavalry leader. He was at times brilliant, but too hotheaded to be consistent and often insubordinate. He despised Tilly, thinking him senile.34 For almost a year the two sides played a game of position. Gustavus spent six months capturing as many cities along the coast as he could in order to maintain his lines of supply. He campaigned into the north German state of Mecklenburg and brought it under his control. The Swedish army was growing with the addition of local mercenaries, and Gustavus was determined to maintain supply depots to keep his army from engaging in pillage and thus alienating the population. By the end of 1630 he had established secure supply bases, but picked up few allies. The elector of Brandenburg refused to cooperate with Gustavus, and in February 1631 the elector of Saxony, John George, called a conference of Protestant leaders to his capital in Leipzig and proposed a defensive alliance to field a neutral force that would support neither Sweden nor the empire. Such an attempt to avoid commitment was futile when the two opposing armies met to fight in Saxony, and John George had to make a choice.

Quick campaigns of misdirection kept Tilly off balance while Gustavus captured Frankfurt an der Oder, which gave him a strong strategic position as well as a riverine line of supply. In early May 1630 he finally convinced the elector of Brandenburg to ally with him, but had to reconvince the wavering elector in June by marching on Berlin and threatening it. Gustavus still met reluctance from John George. Meanwhile, Tilly’s forces expanded a blockade of the city of Magdeburg into a full-scale siege. Gustavus had sent one of his generals, Dietrich von Falkenberg, to organize the city’s defense, but the inhabitants were more worried about their own safety than the overall progress of a war that had dragged on for fourteen years. Hearing of the Brandenburg alliance and fearing a quick Swedish march to relieve the city, Tilly’s forces on 20 May stormed the city and took it. The result was 25,000 of the 30,000 citizens killed in the siege, the pillaging, or the fire that burned most of the city to the ground. Tilly’s army had been starving and looted the city, but the fire destroyed what long-term succor it might have provided. Still hungry, Tilly had no choice but to march on to unplundered Saxony if his men were to be reprovisioned. Russell Weigley comments, “Tilly was an experienced veteran soldier and a generally sound commander, [but] he had mismanaged the logistics of his 1631 counteroffensive. Mismanagement of logistics was not difficult, of course, after much of Germany had been the scene of marching and countermarching for many years and had repeatedly been picked bare of sustenance.”35

Tilly sent word to John George to join him or be invaded. That threat, coupled with the outrage over the destruction of Magdeburg, finally convinced the Saxon elector on 11 September to join forces with Gustavus. It was not a ringing endorsement of the king of Sweden or the Protestant cause, and Gustavus would always have doubts about John George’s dependability. After all, it was only Tilly’s capture of John George’s capital of Leipzig that pushed him to an alliance. They joined forces on the 15th, and two days later the armies were in battle.

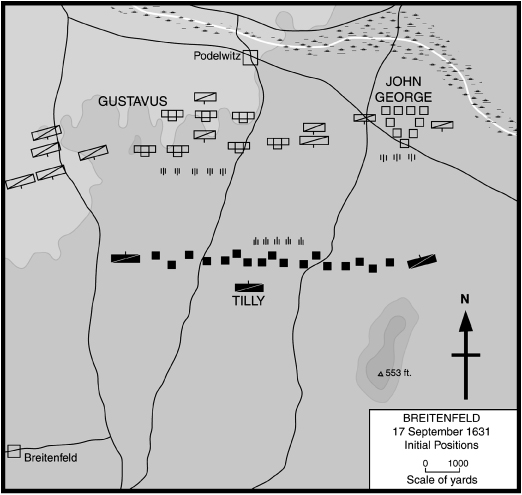

BOTH ARMIES WERE SHORT OF SUPPLIES, but Tilly was expecting reinforcements from the south. A conflict in Italy had just been brought to a close, and imperial forces were on their way to aid him. All he had to do was sit tight in Leipzig once he captured it, fatten up his men, and choose his own time for battle when the relief army arrived. Further, he believed that his veterans could easily handle the Swedes, even though they had made little progress against them in the past several months. In a council of war on the 15th, Pappenheim claimed the neither the Saxons nor the Swedes were anything to worry about.36 Tilly’s army numbered 21,400 infantry and 9,900 cavalry, with 26 artillery pieces.

Gustavus arrived in Düben, twenty miles north of Leipzig, to join with John George on the 15th, just as Leipzig was falling. He commanded 14,742 infantry and 8,064 cavalry plus 54 artillery pieces. John George brought 12,100 infantry, 5,225 cavalry, and 12 guns.37 The primary difference between the two armies was not numbers but experience, since the Saxons were for the most part recently called up militia and had few veterans. The one bright spot in the Saxon army was Lieutenant General George von Arnim, formerly second in command to Wallenstein and a veteran of the imperial campaign against the Swedes in Poland. Unfortunately, he had just assumed the position of army commander the previous June, so he had too little time to whip the troops into shape. From Düben, the combined force marched south to engage the imperialists. Between the two armies ran a small river, the Loder. Although Pappenheim’s cavalry did engage in some minor harassment, Tilly did not attack during the river crossing. Had he placed his troops there and awaited an attack, the outcome could have been radically different. According to Liddell Hart, “The formality of the time is well shown by the failure to fall on Gustavus during this crossing.”38 Hans Delbruck’s explanation is more practical: “[Tilly] did not do so, probably in order to allow his artillery first to fire on the enemy while he was involved in his deployment.”39

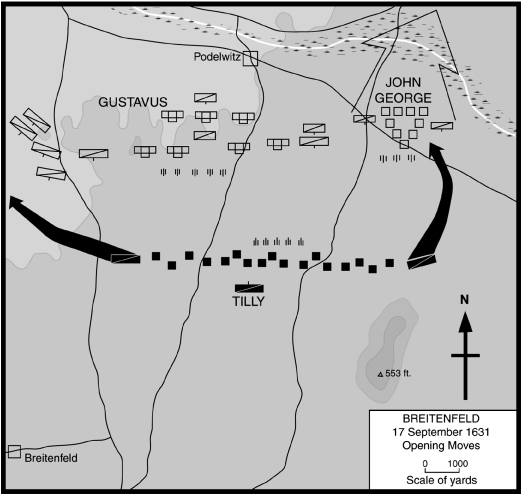

During Tilly’s council of war on the 15th, he proposed staying inside Leipzig and forcing Gustavus to waste men assaulting it or waste time besieging it; after all, reinforcements were just a few days away and could put the Swedes between two fires. The older officers agreed, but the younger officers rallied around Pappenheim, whose nature despised anything but the offensive. Reluctantly, Tilly agreed to fight in the open, perhaps because of taunts that he was too old or afraid to meet Gustavus in battle.40 It is possible that Tilly overruled the more numerous younger officers but gave Pappenheim permission to take 2,000 horsemen in order to reconnoiter the enemy approach.41 This was not a wise move. Tilly had exercised wisdom in deciding to remain behind Leipzig’s walls, but unfortunately for him, giving Pappenheim an inch was the same as giving him a mile. The young cavalry commander would launch a reconnaissance in force that would oblige Tilly to march to the rescue.42 Loosing Pappenheim and expecting him to follow orders to merely scout the enemy was too much to ask. Who knows—Pappenheim may actually have thought he could defeat the Saxons and Swedes by himself.43

Pappenheim’s sally was on the 16th, and Tilly soon began marching his men out of Leipzig. Tilly spent the balance of that day deploying his troops initially in a defensive position, a stance he had rarely taken.44 Accounts vary, but Gustavus seems to have encamped north of the stream on the night of the 16th. He deployed in line of battle while still on the other side of the river, and his men slept in position. As mentioned, Gustavus’s army crossed the Lober against minimal cavalry resistance, then marched forward to face the enemy. Gustavus commanded the center of the army, with Marshal Count Gustav Horn on the left and much of the cavalry on the right under Marshal George Baner. The Saxons under John George and Arnim were deployed on the left flank. The Saxons used the tercio formation but little is known of their exact deployment; possibly it was in a pyramid of units with the point toward the enemy and cavalry on the flanks. With both Saxons and Swedes posting cavalry on their wings, the center of the line thus became predominantly cavalry, but for the mixing of musketeer units as Gustavus had designed.

Tilly was atop a very low ridge and deployed his army with the infantry in the center and cavalry on the wings, the traditional format. Sources disagree on whether his infantry was deployed in twelve or seventeen tercios, but they were divided into imperial troops next to Catholic League troops, who had fought with Tilly the longest. He deployed them line-abreast rather than in the normal checkerboard fashion, probably in order to match the width of the Swedish line. Cavalry was assigned fairly equally to both flanks, Pappenheim commanding on the left and Furstenburg on the right.

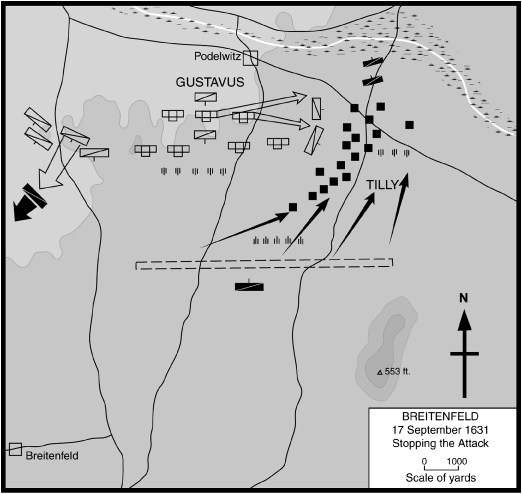

The field is open and slightly rolling, so neither side really had a height advantage. Oddly, half the sources describe a mist on the morning of the 17th while the others describe it as dusty and windy. The Swedish army had received their exhortation from their king; the senior officers had been given a less stirring, more pragmatic talk on the need for discipline and flexibility. They decamped about 9:00 and reached the battlefield near noon. They faced imperial cannon fire as they deployed, but soon Torstensson’s artillery was arranged along the front, and the Swedish forces’ superior number of guns, as well as their ability to load and fire three times faster than the imperial gunners, gave them the advantage as the duel went on for more than two hours. Further, the tercios received terrible damage. The imperial formations were too big to miss, and the effect was disastrous. The forward ranks took the brunt of it, but any ball passing through a man in front still had 10 or 12 more behind him to hit, and for every pikeman who went down there fell an iron-tipped pike to trip fellow soldiers.45

Sometime between 2:00 p.m. and 2:30 the armies began to move. The cavalry charged first, although it is disputed if Pappenheim made the first move (a safe assumption) or Furstenburg. Furstenburg’s assault on the Saxons bore fruit quickly. For mostly untrained militia, the two-hour cannonade had been frightening enough (with some 1,000 Saxons killed). Now they could see the enemy begin to move toward them and hear their battle cry “Jesu-Maria!” Croatian cavalry led the charge, red cloaks streaming and sabers flashing, screaming unintelligibly as they moved forward.46 For the supposedly unwieldy tercios, Tilly had them moving in an oblique, a form of advance to be perfected a hundred years later by Frederick the Great. They initially marched not straight ahead but half right, then pivoted half left toward a Swedish flank opening ever wider as the Saxons began to run. It was vintage Tilly and worked as it often had in the past—at least against the Saxons.47 The Saxon gunners in front broke first, and soon it was learned that John George was galloping away at top speed. The entire Saxon army fell apart and ran, some stopping only to loot the Swedish baggage. The Swedish left was completely broken, and Tilly sent his infantry to take advantage.

On the western side of the field, Pappenheim’s cavalry rode up to the mixed cavalry-musketeer units. They fired their first volley from the caracole, whereupon the Swedes responded with massed musket fire and a cavalry sally. Pappenheim quickly withdrew and moved further to his left in an attempt to turn the flank. Gustavus sent in reserves as Baner pulled back to present a refused flank. Pappenheim’s second caracole fared no better than did his first. Neither did the third, fourth, or even seventh attack. By 4 p.m. his men had taken a beating from the constantly reinforced Swedish line and massed muskets. Pappenheim withdrew from the field as Tilly was leading his infantry against the collapsed Swedish left flank.

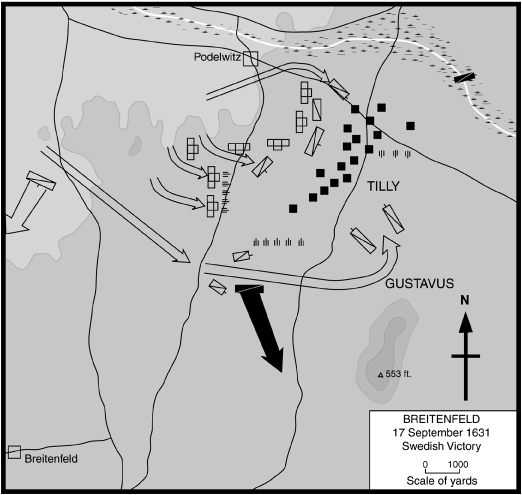

Tilly and Furstenburg were as shocked as Pappenheim had been when they found, instead of an exposed army, another refused flank, this one deployed by Horn. The slow-moving tercios were being easily outmaneuvered by the smaller Swedish units. Horn, however, did not stand and fight, but attacked the imperial forces as they were trying to recover from their charge against the Saxons and change face to meet the new threat. Soon, the imperial ranks were nothing but confusion; and then it got worse. With Pappenheim on the run, Baner’s wing advanced and swung east to occupy the ground where Tilly’s army had stood before their charge. That imperial charge had left all their artillery behind, and the Swedes quickly seized the guns and aimed them at the rear of the imperial army. Musket fire and attacks from the Swedish lines coupled with cannonballs tearing through their forces from behind: it was more than the imperialists could possibly stand. They too began to waver and run, and the Swedes were quick with the pursuit.

It was an overwhelming victory. Tilly, wounded in the battle, fled the field leaving behind 7,600 dead, 6,000 made prisoner on the field, and another 3,000 taken captive the following day in Leipzig, where a tercio and some stragglers had fled. Thousands more were cut down in the pursuit, died of their wounds, were murdered by the Saxon peasantry, or simply deserted. The imperial forces lost all 26 guns and 120 regimental flags. Pappenheim was also among the wounded.48 Swedish losses were 2,100; the Saxons lost 3,000 on the field and while being pursued.

Gustavus led his men to Breitenfeld on an approach march leading to a meeting engagement. After more than two hours of an exchange of opening fire, he received the imperial attack. On defense his right flank disrupted Pappenheim’s attack with much greater firepower than the attacking cavalry could deliver. This led to a separation of enemy forces when Pappenheim withdrew and Tilly attacked the Saxons. For the first time in centuries a force was made up of units able to quickly move about the battlefield, and the Swedish reserves were committed in sufficient numbers to both strengthen the refused flank and to extend it so it could not be ridden around, as Pappenheim had intended. When Baner’s men went over to the offensive, Gustavus could reconstitute his reserve and back up Horn’s refused flank. Once on the offensive, his men exploited the situation by capturing the enemy guns and turning them on the enemy rear. With the imperial force caught in midmove out of its north-eastward attack against the Saxons trying to face about toward the new flank, Horn’s attack was perfectly timed and executed. His men maintained sufficient offensive pressure to back the crumbling tercios against some neighboring woods, but spent so much time attacking their front that several thousand escaped. Pappenheim’s reorganized cavalry arrived on the field to stop close pursuit of the imperial retreat to the west.

The victory was one of the maneuverability of the Swedish units versus the size and weight of the tercio. Conversely, it was a victory of the weight of Swedish firepower over the limits of that produced by the tercio. Gustavus won because his forces could deliver much more firepower than the enemy. The infantry in their extended formations used their superior muskets, and the superior Swedish light artillery moved forward with the infantry, delivering canister fire within yards of the enemy.49 The day of the caracole was dead, that of the tercio was on its deathbed. The battle proved to be a dramatic endorsement of Gustavus’s linear system and cavalry. The Swedish deployment in two lines to make a reserve enabled Gustavus to protect his flanks and differed in no serious respect from the use made of their second lines by Scipio and Caesar. Few military men in Europe missed the lesson to be learned here, as Gustavus himself was to see the following year when he faced Wallenstein at Lützen. The success of the Swedish army and tactics in the war may be gauged by the efforts of Sweden’s opponents to copy them.50

Breitenfeld was also a victory for Gustavus’s methods of training as well as his organization. The mutual trust gained between officers and men as well as king and men gave them the confidence to persevere when almost half the army broke and ran. When all is said and done, the elite military spirit of the Swedes won Breitenfeld. The Saxons buckled under the pressure, but not the Swedes.51

In the days following the battle Gustavus failed to maintain pressure on the defeated Tilly. Instead, he turned his attention more toward Bohemia, where he dispatched John George’s army. This failure to crush his opponent robbed him of the decisive victory Breitenfeld could have been, although it was a major morale boost for Protestants throughout Germany, and therefore brought Gustavus allies, reinforcements, supplies, and money. Some argue that Gustavus should have made immediately for Vienna. Tilly’s broken force was the only one available to stop him, and seizure of the city could have forced Emperor Ferdinand to the peace table.52 Liddell Hart, however, agrees with Gustavus’s plan to maintain secure bases and gather allies: “The scheme was wise and far-sighted, took into calculation all the political and military elements of the situation, and was based on broad, sound judgment. For seventeen hundred years, no one had looked at war with so large an intelligence. … What he has taught us is method, not temerity.”53 Had Vienna been a national or even an imperial capital, its capture may have been decisive, but it was merely Emperor Ferdinand’s home rather than a true seat of government. J. F. C. Fuller’s analysis covers most of the strategic bases that may have led Gustavus to decide against going directly to Vienna. First, the roads were bad, winter was coming on, and Gustavus possessed no detailed maps. Additionally, without the Catholic army destroyed, a move to the south would expose his supply lines. Instead, by moving westward through Catholic territories to the Protestant Palatinate, he would tap into new sources of supply while denying them to the imperialists. And finally, occupation of the Palatinate would bar Spanish Hapsburg access from Italy to the Protestant United Provinces, against whom Spain had been warring for decades.54

With John George leading his army and a band of Bohemian exiles toward Prague, therefore, Gustavus pointed his army southwestward. Although Tilly did quickly recover from his wounds and gather together another army of 25,000 men, there were no major battles. At Wurzburg Tilly faced a badly outnumbered Swedish army but followed orders from his boss, Maximilian of Bavaria, to bring his troops back for home defense. Thus, Gustavus continued—slightly more cautiously—to move to Frank-furt-am-Main (captured 27 November) and thence to Mainz (taken on 22 December). Finally he settled into winter quarters, master of a wide swath of German territory running from the French frontier to the Baltic.

The campaign of 1632 started out with bad news for the Swedes. Tilly had been replaced as imperial commander (though he still commanded the Bavarian–Catholic League troops) with Wallenstein. Fabulously wealthy with massive holdings in Bohemia, Wallenstein was a master of raising and equipping armies. Unfortunately for Emperor Ferdinand, he was without scruples or loyalty to any cause but his own advancement. That is why Ferdinand had given in to pressure from Maximillian of Bavaria to sack him shortly after Gustavus’s army had landed in 1630. To regain Wallenstein’s services the emperor would have to pay dearly in lands and power, but he was desperate after the Swedish offensive had both crushed the imperial army at Breitenfeld and advanced easily through central Germany. Wallenstein agreed first only to a three-month commission to raise an army; accepting command would come later with more imperial concessions. The emperor was desperate, and Wallenstein took advantage of that the situation, demanding unconditional control over the army and whatever territory he conquered, as well as assurance that the emperor would issue no military commands without Wallenstein’s approval.55

The second problem the Swedes faced in 1632 was manpower. Gustavus, Tilly, and Wallenstein were all raising armies, so mercenaries could pick and choose where they wanted to give their services. Thus, Gustavus had been unable to recruit the 200,000-man army he had hoped for, and he was forced to enter into a short-term truce with Maximilian of Bavaria in order to buy himself some time to expand his ranks. Unfortunately, Marshal Horn violated the truce by seizing Bamberg, a Bavarian possession. Tilly massed superior forces at Bamberg and forced Horn’s retreat on 9 March. This hurt Gustavus’s reputation and pushed him into action sooner than he had planned in order to reestablish his military credibility.

The Swedish army was also suffering from the loss of Saxon support. John George had shown his true colors once in possession of Prague by losing his nerve and opening negotiations with the emperor. Nothing came of it, but with Wallenstein returning to his home country with his new army, John George had to decide between the immediate threat of the imperial forces or the distant threat of Gustavus’s wrath and his seemingly invincible army. When Wallenstein communicated to John George that he could return to Saxony unmolested, the elector abandoned Prague and went home. His army commander, Arnim, did nothing to stop him, and Gustavus’s representative, Count Heinrich Thurn, had no sufficient force to do so either. This, coupled with Horn’s mistake at Bamberg, undid Gustavus’s original 1632 strategy. He had hoped to invade though Saxony into Bohemia or, barring that, move north to fight Pappenheim. He now decided to march into Bavaria and fight with Tilly’s reconstituted army. Thus, he could defeat a weaker army before concentrating on the larger one.56

Gustavus retraced his path from Frankfurt-am-Main back to Würzburg and then on to Nuremburg, which welcomed him with open arms. Joining with scattered detachments summoned to the campaign, he marched southward to Donauwörth on the Danube, where he quickly ejected Tilly’s garrison. Gustavus seized the high ground and placed Tortensson’s artillery to bombard the city. The imperial force lost 800 dead in the cannonade and a further 500 prisoners as they abandoned the place.57 Leaving 2,000 men behind to hold the town, Gustavus marched toward Tilly’s army. Tilly had chosen a good defensive position near the town of Rain between the northward-flowing Lech and Ach Rivers, which empty into the Danube. The Lech was in flood, and Tilly had destroyed all the nearby bridges as well as any boats that could be used to either ferry troops across or build a pontoon bridge.

Tilly could hardly have had a stronger position. On the east side the riverbanks were either woods or marsh. Most of his 22,000 men were in a fortified camp at the town of Rain some 800 yards from the river; a redoubt was built halfway between that camp and the Lech. This earthwork was fronted by spiked chevaux-de-frise barricades to the south and west and manned by two infantry battalions and a dozen guns, with heavier 12-pounders in the main camp. All the artillery had the riverbank easily in range. Tilly occupied Rain with a portion of his right wing and Augsburg to the south with a strong detachment. He then distributed the remainder of his army at the points between the two places where the river might be crossed. Small bodies of cavalry were placed at intervals to give warning as to enemy movements. The distance north to south was sixteen miles.58 Certainly no one in his right mind would force a river crossing in the face of such opposition.

Gustavus’s subordinates agreed with Tilly on that point, but Gustavus did not want to spend the time to go farther south looking for a bridge. He thought a delay would give Wallenstein time to join with Tilly and create an overwhelming force. (He was unaware that the new imperial commander had no intention of marching to Tilly’s aid, although he did send a contingent of 5,000 men as reinforcement.) Gustavus knew that the bulk of Tilly’s force would be new conscripts or militia, so he banked on their inexperience to allow him to force a crossing.

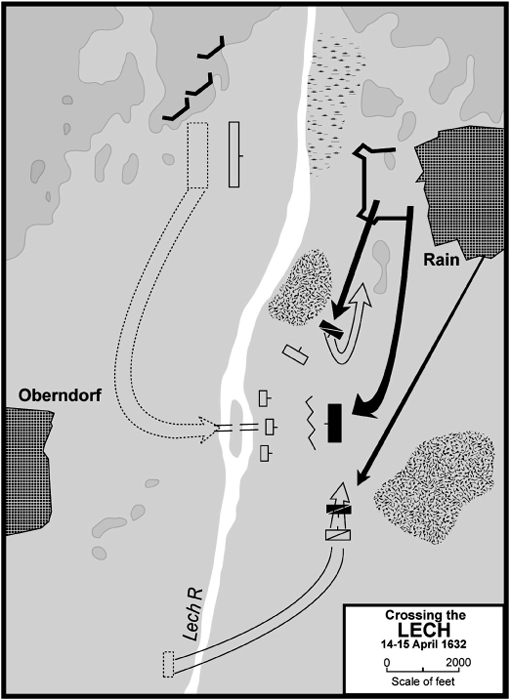

The point Gustavus chose was near the town of Oberndorf, where the Lech made a westward bend and an island was in the center of the river. Gustav deployed his army along the river facing Tilly’s redoubt outside Rain. Instead of attacking, the Swedes dug in, creating three redoubts of their own by the evening of 13 April. Once constructed, they could hold 24 heavy guns that could pound Tilly’s entrenchments; the largest guns would be able to reach the main camp farther to the rear. The 14th saw an inconclusive artillery duel with little damage done to either side.

All of this, however, was a feint. Gustavus had instructed his men to drag boats from the Danube and tear apart local houses for building material, and throughout the night of 14–15 April prefabricated pieces of bridgework were hauled out of Oberndorf to the riverbank opposite the island. An initial force of 334 Finns rowed across to the island and dug in on the east side. By 5:00 a.m. on 15 April the Swedes were ready. The bridge sections were in place, and the Swedes had also constructed supporting earthworks holding 18 guns and 2,000 musketeers. Tilly had been completely deceived.59 At 8:00 a.m. men began swarming across the bridge until three brigades were on the island.

As this was happening, however, some of Tilly’s patrols discovered the action and reported to him. He quickly brought reserves toward the crossing point. Again the Finns were the leading element across to the far side of the Lech, where they began to dig in under fire. Gustavus’s artillery kept Tilly’s men from advancing, but not from felling trees and building a defensive position. To assist the men finishing the bridge and crossing the Lech, Gustavus had stacks of wet hay, green wood, and gunpowder burned to create a thick smoke that blew across the river into the imperial faces.

Both sides reinforced their positions throughout the day. Tilly directed Count Johann von Aldringer to move round the swampy ground, charge with his cavalry those who had already crossed, and seize the bridgehead. Aldringer obeyed the order with alacrity. He turned the marsh and led his men with daring. But the Swedes had second-guessed him and had formed up to await his attack. The cavalry charge, though pressed with vigor, was turned back.60 Aldringer was wounded in the head during the fighting, and Tilly stepped up his activities among the troops, exposing himself to fire to stiffen their morale. During the intense fighting that followed the imperial forces suffered serious losses, and Tilly, continuing to expose himself to enemy fire, was struck in the knee by a 3-pounder cannon ball.61 With the two senior commanders wounded and removed from the field, command fell to Maximilian of Bavaria.

With the fighting so intense at the bridgehead, Gustavus ordered 2,000 cavalry to ride upstream, ford the river, and attack the imperial flank from the south. Imperial cavalry met this thrust but were driven back after some hard fighting. By 6:00 the setting sun brought the battle to an end. Maximilian, with little military training, decided to withdraw the imperial army during the ensuing darkness. He knew that if he abandoned his position he would be exposing his home province of Bavaria to Gustavus’s occupation and potential destruction. Nevertheless, he decided saving the troops was too important, and made the call to abandon the field and Bavaria. It was a masterful retreat, so well conducted the Swedes did not know it was taking place. Not a man or gun was lost in the withdrawal.62 However, imperial forces left behind almost 3,000 dead; Swedish casualties numbered around 2,000.

Gustavus’s crossing of the Lech can stand as a model for such an operation. Whereas much of the battle at Breitenfeld was reaction on his part, the Lech showed his ability to read the terrain, use it to his advantage, and implement surprise. This was a deliberate attack that fully fills its definition: a synchronized operation that employs the effects of every available asset against the enemy defense. Gustavus set the tempo by deploying in full view of the enemy and then holding their attention while implementing his main concentration against a weakly held point. The bridging of the river and the landing on the imperial side was a total surprise, and a deliberate smoke screen probably had not been used in Europe since the Mongols invaded Hungary. His only failure was his inability to exploit or pursue his enemy, because of the skillful retreat of Maximilian’s troops. He did, however, achieve his goal of opening a path into Bavaria, which he proceeded to pillage.

The successful passage of so well defended a position added to Gustavus’s growing reputation. He could have crossed his army farther downstream and attacked from the south without having to fight it out on a bridgehead, but Gustavus himself was impressed with the earthworks the imperial army had constructed and could not believe anyone would abandon such a strong position. So a difficult battle awaited him no matter what the avenue of approach. In an analysis for the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Major Mark Connor writes, “Though one of his least famous actions, the passage of the Lech River is a shining example of his ability to recognize his army’s condition, establish its goal, and concentrate decisive combat power—all the while protecting his soldiers.”63 The key was the misdirection Gustavus employed, which probably would have made Subedei smile.

GUSTAVUS NEXT HAD TO MEET the redoubtable Albrecht von Wallenstein, once again the commander of imperial forces. Born in 1583 to poor but noble parents, Wallenstein served in wars against the Turks and Hungarian rebels, coming to the notice of the Hapsburg monarchy. In 1609 he married a wealthy widow; she died in 1614, leaving him a very rich man. He married into more wealth in 1617 and financed a cavalry squadron that same year to fight against the Venetians. By the time the Thirty Years War broke out in his home country of Bohemia the following year, he was a powerful and influential man in the eastern Holy Roman Empire.

In the early years of the war Wallenstein fought for the imperial cause and rose in rank to become Duke of Friedland in 1625. He gained more land and income as the war progressed, becoming Duke of Mecklenburg after helping to defeat the Danes in 1628. His increased military and political standing proved threatening to many of the imperial nobility, since he had no loyalty to empire or church. Through the urging of many of the nobles, primarily Emperor Ferdinand’s son Maximilian of Bavaria, Wallenstein was removed from his command in 1630, just after Gustavus had landed on the Baltic shore. Wallenstein went home, managed his estates, and bided his time, for he knew the time would come when Tilly would fail and the emperor would be in need.

At Rain, Wallenstein was in no mood to march to Tilly’s aid, and his command position made him answerable to no one. Much more a strategist than a tactician, Wallenstein grasped that Gustavus continually kept his mind on his lines of communication back to Sweden. Liddell Hart comments: “Wallenstein, the first grand strategist, appear[s] to have grasped the principle of unity of command, appreciating that to counter Gustavus, the absolute chief of a military monarchy, equal power and freedom of action was essential.”64 Although the Swedes ran rampant through Bavaria, Wallenstein did nothing to stop them. After all, that was Maximilian’s territory; after Maximilian had played a key role in having Wallenstein removed from command two years earlier, why should he care what happened to Bavaria? Wallenstein was busy expelling the Saxons from Bohemia, which not only secured his own base, but threatened Swedish supply lines and bases. Thus, he saved Vienna without having to defend it.

Wallenstein had raised an army of 40,000. Like Gustavus, he realized the value of regular pay and supply for the troops’ morale, and his territory of Friedland provided plenty of both. In early summer he summoned Maximilian to bring his Bavarian army to join him. The two joined forces at Eger and with 60,000 men moved toward Nuremberg. Gustavus had at first planned to march on Saxony to revitalize John George, but news of the huge imperial army gave him second thoughts. Instead he retreated into Nuremberg’s friendly environs, but with only 20,000 men. Wallenstein approached the city in July 1632 but did not use his three-to-one manpower advantage for an assault. Instead, he established himself in a strong encampment on rugged ground around the castle of Alte Veste to the southwest. There he waited on hunger to do its work, although Gustavus had laid in two months worth of supplies. There were, Wallenstein calculated, insufficient supplies for men and horses, so Gustavus would have to fight or starve. Either way Wallenstein was in a good position, for he was able to maintain his own supply situation fairly well for a time.65 In August Gustavus’s chancellor Oxenstierna arrived with a further 30,000 men; Wallenstein did nothing to stop their juncture. He believed that more men in the city meant quicker starvation, even though he was finding it increasingly difficult to keep his 60,000 as regularly fed as he had hoped.

GUSTAVUS WAS FINALLY FORCED to challenge the imperial forces. In early September 1632 he launched an attack on Alte Veste, but the rough terrain made it difficult for his men to maneuver and bring their artillery to bear; after severe losses Gustavus withdrew back into Nuremberg. His reputation had taken a beating as much as his army had, and with poor food and morale his German soldiers began deserting and his allied leaders became disaffected. He finally abandoned the city after trying futilely to interest Wallenstein in a peace treaty. He headed for Austria, hoping to consolidate his hold on the Danube and prepare for the following year’s campaign.

Maximilian urged a pursuit, but Wallenstein was looking at a bigger picture. With his joint armies he intended to race for Saxony; thus either he would come upon John George and Arnim alone and force them to make terms, or he would draw Gustavus off from Austria. But Maximilian had had enough of Wallenstein, and he took the rest of his army home to reoccupy and hopefully rebuild Bavaria.66 With his army reduced by one-third by Maximilian’s retreat, and then reduced further by starvation and desertion (after all, there was no victory in which to gather loot), Wallenstein himself was seeing his army dwindle to about 30,000—roughly the same as Gustavus’s if John George joined him. Learning that the Swedes were heading once again for the Danube, Wallenstein followed his plan to march on Saxony in early October. So each planned to raid, make a foray into the each other’s base, and, he hoped, put his adversary on the defensive.67

Gustavus once again showed his abilities, even after the recent setback at Alte Veste. Learning of Wallenstein’s move, Gustavus reversed course and followed him speedily, force marching his men some 400 miles in seventeen days to catch the imperial troops before they could meet the Saxons. In early November Wallenstein captured Leipzig, joining forces with Heinrich Holk and Pappenheim (who had been campaigning in the north). Gustavus met his ally Bernhard, Duke of Saxe-Weimar, with reinforcements at Erfurt, some 50 miles southwest of Leipzig; together they had just under 20,000 men. They rested there for five days before slowly moving toward Leipzig. On 8 November they captured the village of Naumburg and began erecting earthworks; they were now 20 miles from Leipzig.

Wallenstein, who had intended to march on Torgau to seize the bridge there and isolate the Saxon army, now turned back to meet the Swedes. Outside Weissenfels, on 12 November, his army deployed as Gustavus rode nearby with a cavalry reconnaissance. Gustavus withdrew to Naumburg to strengthen his defenses while sending a message to Duke George of Lüneburg to bring his 2,000 cavalry from Torgau to join him. Seeing the Swedish defenses, Wallenstein withdrew toward Leipzig. What happened next is open to some debate. William Guthrie’s 2002 detailed account of the battle follows the traditional viewpoint: “[Wallenstein’s] next decision is difficult to understand; in fact it was one of the most bizarre of the war. On November 14, Gustav heard, to his mingled joy and disbelief, that the Imperial army had broken up into corps and gone into winter quarters. … Wallenstein, it would seem, assumed that the camp at Naumburg was the Swedish winter quarters, that the king was suspending operations for the year.”68 The imperial commander spread his men out in various directions to spend the next few months pillaging the Saxon countryside to stay alive and at the same time needle John George. He was sure that if the Swedes moved, he could rally his army soon enough to fight. Guthrie notes that Wallenstein was suffering from gout and also was in a deteriorating mental state; he believed that the Swedes were suspending operations “because he wanted to believe it.”

Others argue that Gustavus’s entrenchment was merely a feint meant to confuse Wallenstein, and that the imperial decision to divide the army and live off the land until battle loomed was a surprise. Wallenstein, however, was not going into winter quarters.69 He could not dislodge Gustavus from his strong position, and he could not feed his army on local supplies. Further, Pappenheim had been successful in controlling northern Saxony, and wanted to return to there and resume his independent command. Wallenstein agreed, on the condition that he capture Halle (some twenty miles to the northwest of Leipzig) on the way. Pappenheim departed with 5,000 men, about 2,000 of whom were cavalry. Wallenstein was in command of 15,000–18,000, and Count Matthias Gallas was marching from Bohemia with a further 6,000–7,000 to establish himself at Grimma, some 20 miles southeast of Leipzig. So with a respectable force on hand and two other forces within a day’s march, he seemingly felt secure.

The problem was that Gustavus was also only a day’s march away and a surprise attack would leave Wallenstein without assistance. What happened next is one of the “what-ifs” of this campaign, and perhaps the war; the whole history of the next two days, from the Swedish point of view, was a string of accidents and cruel strokes of fate.70 Wallenstein positioned a small force at Weissenfels, halfway between Lützen (his headquarters) and Naumburg. Early on 15 November he sent a few hundred Croat cavalry under Count Rodolfo di Colloredo to fetch them and bring them back to the main body. Just as they were joining up, however, Gustavus’s army approached in battle formation. The small imperial force retreated to a marshy stream called the Rippach and threw together a hasty defense on the eastern side. The Swedish advance guard could not estimate the enemy numbers in the trees on the far bank, and so awaited the remainder of the 18,000 men to arrive. Colloredo, usually considered a mediocrity, sized up the situation at a glance and acted correctly. He sent warning to Wallenstein while deploying his meager forces along the stream. For two hours, they held up the Swedish advance. By the time Gustavus was able to break through and reach Wallenstein’s headquarters at Lützen, it was already dark, and battle was impossible until the next day.71 If the small imperial force had indeed been withdrawing, an hour’s delay on Gustavus’s part would have made his approach unopposed. Likewise, a more aggressive Swedish advance guard could have broken the small force and Wallenstein would have been caught unawares, his army forced to flee or fight unprepared. As it was, the small force of cavalry under Colloredo managed to prevent the imperial army from suffering a potentially devastating assault.

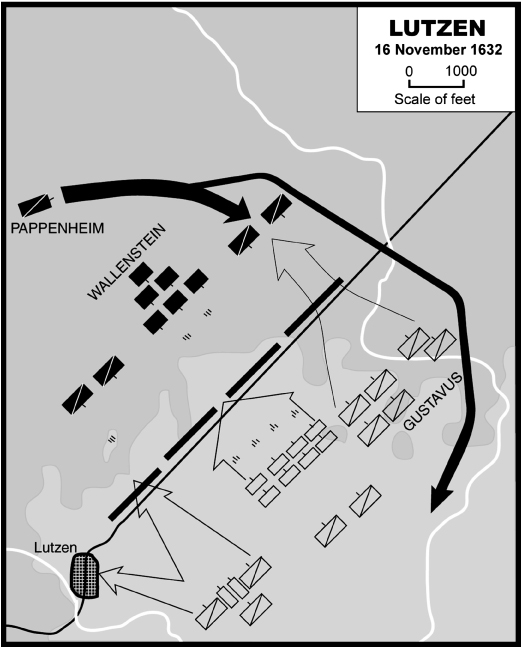

Gustavus’s men were marching in battle order, so they encamped on the eastern outskirts of Lützen. His deployment looked the same as it did at Breitenfeld, minus the Saxons. After sending a horseman to Pappenheim to get his force back from Halle on the double, Wallenstein spent the night deploying his men and digging defenses. He formed his infantry in the center in three lines with five regiments in front, two in the second line, and one in reserve. The 1,000-man infantry brigades deployed in the center were, in effect, battalions; Wallenstein had clearly realized the maneuverability of smaller formations and had abandoned the tercio.72 Cavalry units were on the flanks: Colloredo’s Croats on the imperial right, Field Marshal Heinrich Holk on the left.73 The artillery Wallesntein placed both in front of his infantry and on his right near some windmills on the edge of town. Between the two armies ran the road to Leipzig, in this stretch a causeway with ditches on either side. Wallenstein wisely placed musketeers on his side of the road in order to be protected as they lay down fire on the advancing Swedes.

By dawn both sides were in position, and both were waiting on cavalry to arrive. Gustavus learned, however, that Duke George was not coming from Torgau, being ordered by Arnim to stay in place and protect Saxony. On the other side of the field Wallenstein waited anxiously for Pappenheim. In spite of the bad news that he would receive no more cavalry, Gustavus was in a good mood and ready to fight, having a slight edge, 19,000 men to Wallenstein’s 16,770, but he knew that every passing minute worked against them: the enemy had 10,000 reinforcements en route, while Gustavus had none.74

Indeed, more than minutes were passing. The day broke on 16 September with fog and mist, sufficient to hide both armies. Gustavus’s plan was to hold the imperial center and right wing while swinging his personally led cavalry against the imperial left. He had a 1,000-man advantage in numbers on that side, but as it turned out he needed more. When the fog finally lifted at 11:00 he quickly sent his men forward as the imperial artillery opened up. The first problem for the Swedes came almost immediately. The hidden musketeers in the ditches surprised the attacking cavalry, which could not easily jump the ditches, and paths across them were at irregular spots. In seconds, the Swedish cavalry was milling about while imperial musketeers fired into the disordered masses.75 The infantry following up were able to clear the ditches, but the impetus was lost. The advance continued, however, and made slow but steady headway against the imperial left wing. At the same time, on the western flank, Wallenstein ordered the town of Lützen to be burned, and the smoke blew directly into the attacking Swedes, creating visibility just as limited as it had been under the morning fog.

Duke Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar commanded the Swedish left and was the most affected by the smoke. His moved his wing forward under musket fire from the walled garden around Lützen and from the artillery to his front at a windmill. Soon, however, the smoke hid his movements and he was able to cross the road, drive away the musketeers in the ditch, and break the cavalry screen. That was the end of his luck, however; when cavalry reserves attacked him and the gunfire from the walls resumed, he had to withdraw back across the road.

Seeing Gustavus’s advance coming on his left, Wallenstein ordered reserves to help hold the line. Fortunately, Pappenheim arrived at noon with 2,300 horses and took command of the crumbling flank. His men were tired from the all-night march, but the young commander’s legendary energy would not be denied. He would lead the imperial left-center into the gap made by Gustavus’s cavalry attack, while cavalry units would hit Gustavus’s flank and move around his rear, rolling up the Swedish line. That was the plan, at least.

Unfortunately for Pappenheim, by the time his assault was launched around 1:00, his enemy had advanced to the road. The Swedes had improvised a defensive line utilizing the musketeers and regimental guns, and Pappenheim’s advancing troops were immediately hit with a wave of firepower against which they stood little chance. Pappenheim himself was one of the first to fall, struck by two musket balls and a cannon shot.76

Even without their leader, Pappenheim’s men continued the attack. Croat cavalry struck the far right squadrons and drove them back, then rushed past them to swing wide and strike the Swedish baggage park. Imperial general Ottavio Piccolomini, taking over from Pappenheim, slowly pushed the Swedes back across the road. Displaying his unparalleled battlefield presence once again, Gustavus rallied the remnants of his original attack, sent for reserves to reinforce his right flank, and fell on Piccolomini. The imperial commander quickly turned to face Gustavus’s charge, allowing the badly mauled Swedish infantry to dig in along the road.

It was somewhere in this confusion, about 1:00, that the unthinkable happened: Gustavus was shot and killed. Word spread quickly on both sides. It did not have the effect one might suppose, however. Piccolomini, under Holk’s command, had withdrawn according to orders to rally around Wallenstein, who apparently did not know of Pappenheim’s fate. This left the imperial center-left virtually leaderless. On the Swedish side some, realizing that their leader had fallen, fled, but Gustavus’s chaplain began singing hymns and rallied the troops. He would not confirm the death and stopped the potential flight as Gustavus’s second in command, Bernard Saxe-Weimar, quickly reorganized the units along the road. The Swedish second line was under the command of Field Marshal Dodo von Knyphausen, a steady veteran. He kept the reserves under strict control, assuring them that the king was only wounded. He fed units to Bernhard on the left for a second assault on the windmills, which was also beaten back in hard fighting. Knyphausen sent units to the road to reinforce or replace those that had taken the brunt of the fighting.