King of Prussia

That was the tremendous respect which the king gained in the eyes of the opposing commanders. Why did they so seldom take advantage of the favorable opportunities that he offered them frequently enough? They did not dare. They believed him capable of everything.

—Hans Delbruck

THE TERRITORY OF BRANDENBURG, around the city of Berlin, was the birthplace of what would become the mighty Prussian state and, eventually, modern Germany. In 1415, the Holy Roman emperor Sigismund defaulted on a loan to Frederick Hohenzollern. Collateral for the loan was the electorate of Brandenburg. In the wake of the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410, the order fell into decline, and in 1466 the Knights named a Hohenzollern as their new grand master. In 1525, the grand master converted to Protestantism and privatized the Knights’ land for himself and his heirs. Two lines of the Hohenzollern family agreed to merge the territories in the event of one line having no heir; such an event occurred in 1618, and Brandenburg-Prussia came into official being.

Late in the Thirty Years War Frederick William, also known as the Great Elector, became leader of the province. He suppressed local governments and built up an army of 30,000 men with which he sought to curry favor with the Holy Roman emperor. Building on Dutch and then French military models, the Brandenburg-Prussian army became respected, if not dominating. His son Frederick became elector in 1688 and remained subservient to the empire. Under his leadership the army grew to 40,000 and during the War of the Spanish Succession, Prussian officers learned warfare from the master commanders Marlborough and Eugene. In return, they gained international respect as well as power and prestige. Bavaria, by backing the losing side in the war, was on a downward slide while Brandenburg-Prussia became the preeminent German state. In 1701 Frederick took the title king of Prussia, as Brandenburg was still under imperial authority. Upon his death in 1713 his son became King Frederick William I.

King Frederick William continued transforming the army into a force as dominant as its state. Prussia became a military state; 83,000 men served out of a population of 2.25 million (although many of the recruits were foreigners). By the time of his death in 1740, Frederick William’s territory was tenth largest in Europe, his population thirteenth largest, but his army stood at fourth largest. To accomplish that feat took more than military manpower; it needed the efforts of the entire population. For Frederick William, this meant bringing the entire population into a semimilitary lifestyle. Everyone from noble to peasant acted like soldiers, and the economic and social life of Prussia revolved around the army. Discipline for the entire population was the order of the day.1

Aided by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau (a veteran of service under Marlborough), the army became a model of discipline and precision. Leopold developed the cadenced step and introduced the iron ramrod, while Frederick William introduced the plain dark blue uniform, which broke from the tradition of more decorated and fashion-conscious uniforms. Christopher Duffy points out that “[t]he new style accorded well with the movement of Pietism which was abroad among the Lutheran people and nobility, and which stressed the virtues of service, honesty and industry.”2 Frederick William created not only a large army but the best-drilled and most disciplined one in Europe. Nothing to him was as important. “He transformed the royal parks of Berlin and Potsdam into parade grounds,” Duffy notes. “In his creative work for the Prussian army Frederick William’s achievement far surpassed the activity of his more famous son, Frederick the Great. Stout, bad-tempered Frederick William was the man who regularised the recruiting of the army at home and abroad, who cemented the peculiar bond between the King of Prussia and his officer corps.”3

Personally, Frederick William was a hard taskmaster with his family as well as with his troops. He preferred the company of rowdy friends (known as the “Tobacco College”4), though he spent sufficient time with his wife to father fourteen children. His disdain was saved particularly for Crown Prince Frederick, born in 1712. The young man was his mother’s son: quiet, studious, artistic, and (worst of all in his father’s eyes) Francophile. His father harassed him at every possible turn, in public and private. Pushed to the breaking point, Frederick at age eighteen made the foolish mistake of running away to France with a close friend, Lieutenant Hans von Katte. As a result Frederick was imprisoned for fifteen months while von Katte was beheaded.

All of this harsh treatment was not without its long-term positive effects. Early on Frederick learned to still his temper and tongue, and he developed a cold and calculating nature, which he used against his father. He could stand expressionless before his father’s tirades, knowing that such passivity angered the older man even more. “The less Frederick William was able to hide his emotion from others, the more the crown prince learned to do so,” writes Gerhard Ritter. “If we ask what character traits first became recognizable in the behavior of the adolescent boy, we discover above all an amazingly stubborn self-assurance, ambition which could not be deflected by any humiliation, the power to mask his feelings from others, and … great cunning in getting his way.”5 The intellectualism he developed under his mother’s tutelage served him well after his release from prison. Frederick acted as though he had learned the lesson his father had intended, and he became an untiring student of military history and the nuts and bolts of operating Prussia’s army. He also seemed to cooperate in the political marriage his father arranged for him in 1733. Although there was a wedding, one can hardly say there was a marriage; Frederick barely acknowledged his wife, Princess Elizabeth Christine of Brunswick, and they never had children.

Frederick received a colonelcy upon his release from prison and devoted his public life from that point forward to his army and his nation. In 1734 he saw his first combat. He served with a Prussian contingent fighting under the command of Eugene of Savoy in a campaign against France. Philip Haythornthwaite writes, “Eugene affirmed that Frederick showed all the intelligence, courage, and skill to become the greatest soldier of his time, and this recommendation so impressed Frederick William that he appointed Frederick as Major-General. … By the closing months of the life of Frederick William, Frederick had so rehabilitated his reputation that the King accepted him as a worthy successor.”6

After his death, Frederick William’s Political Testament showed him to be a much deeper intellect than he portrayed. He had seemed a caricature to much of Europe, rejecting the trappings of monarchy for the company of soldiers; even odder was his apparent fascination with overly tall soldiers. He formed a grenadier regiment of 3,000 men all more than six feet tall and had some tall cavalry troopers as well, though they were rarely good horsemen. The surest way to curry favor with him was to send him some tall men for the regiment.7 The Testament disclosed, however, that much if not all of this public image was a false front: Duffy quotes the Testament: “Only under the guise of these spectacular eccentricities was I allowed to gather a large treasury and assemble a powerful army. Now this money and these troops lie at the disposal of my successor, who requires no such mask,” he wrote in Political Testament.8 If indeed Frederick William’s public persona was a fraud to ensure the successful future of his country, as the opening of his Political Testament indicates, he ranks as a great actor and brilliant political mind. It is his son who takes on the sobriquet “the Great,” however. With his calculating personality and his military inheritance of three generations dedicated to building an army, Frederick on becoming king in 1740 was poised to earn his nickname.

ON THE SURFACE, armies and warfare of the mid-eighteenth century differed little from half a century earlier when Marlborough dominated European battlefields. Indeed, outside Prussia such was the case. Inside the country, however, the future of warfare was being created. The Prussian kings had been as dedicated to making a national army as Gustavus Adolphus had been in Sweden. Although as king and commander Gustavus had earned the loyalty of the Swedish army, in Prussia the state became the object of loyalty, more so than the monarch. Much of that devotion results from the national focus on military production mentioned earlier. The soldiers were recruited by geographic region (the cantonment system) and quartered in private homes in their neighborhood when not in fighting season. This created a bond between civilian and soldier. Barracks became a more common sight in Berlin as Frederick’s reign progressed, but in the early days the practice of local garrisoning meant “the troops could be kept together under close supervision, and assembled quickly and quietly in the event of mobilisation.”9 The “close supervision” would be exercised by the local noble, whose military service was not optional.

“Although a new man made a passable soldier inside twelve months, it took six years to mould a really steady, reliable infantryman,” notes John Childs.10 Underlying all the Prussian military before and after Frederick was discipline, such as had not been seen since Sparta. In 1747 Frederick wrote, “The discipline and the organization of Prussian troops demand more care and more application from those who command them than is demanded from a general in any other service. If our discipline aids the most audacious enterprises, the composition of our troops requires attentions and precautions that sometimes are troublesome.”11 Although the use of the cantonment system aided somewhat in maintaining unit cohesion, the large-scale use of foreign troops led to an almost constant problem with desertion. This was addressed in many ways: “night marches were avoided, and men detailed to forage or bathe had to be accompanied by officers so that they could not run away. Even pursuits of the enemy were strictly controlled ‘lest in the confusion our own men escape.’”12 Everything was done, especially when on campaign, to make sure officers always had eyes on their men. Haythornthwaite describes how: “measures taken to enforce this discipline were draconian: physical beatings by NCOs, branding, running the gauntlet (under which the prisoner could die) and execution—barbaric treatment resulting from Frederick’s belief that a soldier must fear his superiors more than the enemy.”13 Minor punishments were left to officers’ discretion, primarily beatings with sticks or fists. Worse offenses could be punished in a variety of ways, including “chaining to bedsteads, the Eselsreiten (riding a sharp-backed wooden horse), and the painful process of Krummschliessen by which alternate arms and legs were bound tightly together by leather straps. Incorrigible thieves were branded deep on the hand … while men involved in desertion plots sometimes had their noses or ears cut off in addition to the other punishments that came their way.”14

As mentioned previously, the key individual in developing the theories of Prussian military doctrine was Leopold I, nicknamed “the Old Dessauer.” After his service with Eugene in the War of the Spanish Succession, Leopold became field marshal and chief of staff. While the kings employed the army and even trained with it, Leopold was the potter who molded the clay. Under his command, “the officers discovered that they were expected to make military duties their first concern in life, even in peacetime, which was something of a novelty in contemporary Europe.” And it was not only the officers who were influenced by him: “The Old Dessauer was an expert in the formation of crown princes, and for the instruction of Frederick he compiled a Clear and Detailed Description, which was based on the orders of the day which were issued in the campaigns against the Swedes between 1715 and 1720.”15

Thanks to Leopold, the Prussian infantry had also become virtually the only force in Europe employing the cadenced march, in which every soldier started off on his left foot then marched in step to an accompanying drumbeat. Using this cadenced march resulted in tighter formations that were able to maneuver much more quickly. This allowed the units to advance farther before having to stop and dress the lines, and also created more compact columns to employ a greater mass of firepower.16 Before this time all armies marched in route step, with no coordination at all. This meant that units gradually became more spread out while on the march, making it more difficult to form up and prepare for maneuver. The Prussian army stayed in step, so stayed in ranks. Deployment was therefore far more rapid and organized. Childs points out that “[o]nce the cadenced step had been universally adopted much of the hassle and uncertainty of taking troops from column into line disappeared, as the intervals between ranks, battalions and files could be maintained precisely on the approach march and translated direct into the correct spacing in the battle line by a simple wheel to the left or right. Frederick the Great drilled his infantry to the point where they could swing out of column of march into line of battle within a few minutes and advance straight into the attack.”17 Other European armies might take as much as two hours to perform the same action. Frederick wrote that “promptness contributes a great deal to success in marches and even more in battles. That is why our army is drilled in such a fashion that it acts faster than others. From drill comes these maneuvers which enable us to form in the twinkling of an eye.”18

Upon assuming the throne in 1740 Frederick began expanding his army, primarily the infantry, with the intent of doubling its size from its existing one of 80,000. (That goal was not reached until the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War in 1756.) Between 1740 and 1743 fifteen infantry regiments (at 1,700 men each) were added, as well as twelve regiments designed primarily for garrison duty in Prussia’s forts. The Prussian infantry consisted of grenadiers, two companies per regiment, chosen for their reliability and aggressiveness. They needed both traits, as these units often took the greatest casualties. The rest of the infantry, fusiliers, were the standard troops, using muskets of less-than-stellar quality. Based on the Liege-manufactured musket of Frederick William’s day, Frederick’s proved to be “a clumsier and more eccentric version of the typical military flintlock of the day. … [T]he Prussian musket remained one of the worst in Europe. Firing was a decidedly uncomfortable experience, for the trigger was set too far forward in the guard, the comb of the butt rose so high as to make aiming almost impossible, and … the long barrel, the bayonet and the cylindrical ramrod combined to make the weapon muzzle-heavy by three pounds.”19 Still, it was a rugged weapon firing a .75 caliber ball. Since discipline demanded reloading and firing at speed, aiming was ignored; however, the shots were famous for falling far short of their target owing to the weapon’s imbalance.

In the Seven Years’ War Frederick filled his ranks with militia and “free battalions,” or mercenaries. During the War of the Austrian Succession, he developed a small light infantry organization, used more as scouts and guides than skirmishers; they developed into that more typical role in the Seven Years’ War and afterward.

For the most part Frederick’s army fought in the standard linear tactics of the day, with two lines roughly 200 yards apart, each made up of three ranks of musketeers (although he often used only two ranks when his manpower was short). Firing was done by platoons, the formation Leopold had learned in Marlborough’s service. The Prussians held two distinct advantages: a far more rapid deployment on the battlefield, and an increased rate of fire that resulted from the constant training and discipline. In training, the Prussian soldier could fire five shots per minute, almost twice that of his enemy; in combat, however, both rate of fire and regularity in volley fire diminished, as was true in all armies. Still, the Prussians always threw more lead than their opponents could. Had they had better muskets, the damage would have been that much greater. Childs notes another disadvantage: “The intention to break the opponent’s morale rather than his bones produced another limitation upon accurate musketry. The advantage went automatically to the side which loosed off more volleys in a given space of time, and this led Frederick the Great to put more emphasis upon speed of fire and rapid reloading than upon accuracy.”20 Still, battles of the time were not long exchanges of musket volleys, but more dependent (especially in the Prussian army) on the bayonet charge. Starting in 1741 Frederick ordered the bayonets to be permanently affixed when soldiers were on duty. He wrote in 1747, “It is not fire but bearing which defeats the enemy. And because the decision is gained more quickly by always marching against the enemy than by amusing yourself firing, the sooner a battle is decided, the fewer men are lost in it.”21 In retrospect, he should have focused more on improving his firepower. In biographer Christopher Duffy’s opinion, “For the best part of the first two decades of his reign Frederick was deluded into thinking that the awe-inspiring sight of advancing troops was a more effective weapon than the bullet. This miscalculation must be regarded as his greatest error in his capacity as military technician.”22 By the time of the Seven Years’ War, Frederick had become more appreciative of the benefits of firepower.

Frederick’s most famous contribution to contemporary warfare was the oblique attack. This was a wise adaptation given that he was usually outnumbered in battle. “There can be no doubt that Frederick, who once wrote that he had read just about everything that had ever been written on military history, already had in mind the thought of the oblique battle order when he went into his first war,” writes Hans Delbruck.23 The concept goes back to Epaminondas of Thebes and his use of the refused flank at the Battle of Leuctra. In later times, the concept was discussed by the first Duke of Prussia (1500s), Raimondo Montecucculi (1600s), then the French soldier and theorist the Chevalier Folard, Jacques François de Chastenet of France, and the Austrian Ludwig Khevenhüller in the 1700s. Therefore what Frederick did was to update and fine-tune a theory that had been discussed for a long time.24 It began its evolution in peacetime experiments in 1747, but hints of it might be seen as early as the Battle of Chotusitz in 1742. The maneuver started with the concept of holding back one wing of the army as the rest partially wheeled into the enemy flank. According to Bevin Alexander, “A commander should strengthen one wing of his army and employ it to attack the enemy flank, while holding back another, smaller wing to threaten the enemy’s main force and keep it from changing position. Since the enemy army would already be deployed, it could not switch troops fast enough to the threatened flank before Frederick’s columns struck. Frederick said an army of 30,000 could beat an army of 100,000 using this method.”25

Over the years it evolved into an attack in echelon, with the refused units coming into the attack successively against the enemy flank. Such an advance limited the enemy’s ability to redeploy and attack the Prussian flank, as it was refused. So unlike Epaminondas attacking with only one unit and holding the others back, Frederick would have the entire line advance, with fresh units coming into action along the line. This style of advance had two main advantages. Each unit could more easily maneuver itself over broken ground if it was not worried about maintaining an extended line. It also fooled the enemy, as Brent Nosworthy notes: “Looking at the Prussian infantry from a distance, the enemy was unable to discern the formation being employed, and, in fact, thought that the Prussian infantry was advancing in total chaos. The enemy was able to see that the infantry line was fragmented; but was not able to perceive any ordered relationship between each division of line.”26 Frederick used this movement to fulfill his primary battlefield goal, to put maximum force at the enemy’s weakest point. Thus, even an army outnumbered overall could attain localized superiority. Frederick believed unwaveringly in the strength of the oblique attack, insisting that other armies ought to be employing it: “All weak armies attacking stronger ones should use the oblique order, and it is the best that can be employed in outpost engagements; for in setting yourself to defeat a wing and in taking a whole army in the flank, the battle is settled at the start. Cast your eyes on this plan.”27 In what could be equally advantageous, the oblique order could cover a withdrawal if the attack didn’t go well, as happened at Prague in 1757. R. R. Palmer describes how the maneuver accomplished either purpose: “Frederick’s purpose in favoring this type of battle was, in case of success, to gain a quick victory by rolling up the enemy’s line, and, in case of failure, to minimize losses, since the refused wing maneuvered to cover the withdrawal of the wing engaged. Frederick’s superior mobility and coordination gave a special effectiveness to these flanking movements.”28

Although he inherited the best possible infantry, at the outset Frederick’s cavalry was the shame of his army. Haythornthwaite describes the cavalry as “[p]roficient only at ceremonial drill on foot, [and] Frederick claimed that they could not manage their horses and were commanded by officers totally ignorant of what was required of them in action. The cuirassiers he described as ‘giants on elephants,’ who could neither manoeuvre nor fight, and who fell off their horses even on parade; they were so bad, he claimed, that ‘it isn’t worth the devil’s while’ to use them.”29 This became dangerously clear to Frederick at his first battle as king, at Mollwitz in 1741. His cavalry fled from the Austrian cavalry, which would have won the battle had they not been turned back by the stalwart Prussian infantry. Frederick’s improvements in this arm, therefore, were both quick and effective. Frederick recruited cavalrymen not from the society as a whole (as with his infantry) nor from the landed gentry and nobility (as with his officers). Instead, he looked to the better-off peasants who had sons who were used to being in the saddle and (initially, at least) could provide their own mounts. The foreign-born recruits came from the same condition. This provided the Prussian military with young men who already were familiar with what a horse could do, and they proved more loyal, as Hawthornthwaite notes: “The cavalry contained the smallest proportion of desertion-prone impressed peasants and unreliable mercenaries; indeed, Frederick’s Instructions indicate that the presence of cavalry picquets were a principal discouragement to desertion, so the cavalry had to be reliable.”30 Although they were trained to operate in as disciplined a manner as were the infantry, they did not undergo the same harsh discipline. The new cavalry arm was first organized and led by Frederick Wilhelm von Seydlitz, “probably the most gifted leader of men in eighteenth-century Prussia. … Seydlitz believed that it was not enough for an officer simply to order a man to do something: he must be in a position to show him how it ought to be done, and to do it in an exemplary style.”31

Frederick removed the giants from the cavalry, although he knew that size and power were necessary to his plan of reintroducing shock to cavalry tactics. The cuirassiers were the heavy cavalry, named for the heavy iron breastplate, or cuirass, that they wore. These were the descendants of the knights of medieval times, armed with a straight sword, two pistols, and a carbine. The dragoons had been developed in the Thirty Years War in order to provide mounted infantry; by Frederick William’s time they were full-fledged cavalry but lacked the armor. They carried a longer carbine with a bayonet and a straight sword. The hussars, or light cavalry, originated in Hungary and were used primarily for patrol work, raiding, and flank security. The hussar concept was slower to catch on in Prussia. “For a long time the Prussian hussars could be written off as just another of Frederick William’s bad military jokes—more gaudy, perhaps, than the Giant Grenadiers, though not nearly as expensive,” Duffy writes. “The king himself admitted that ‘a German lad does not make such a good hussar as an Hungarian or a Pole.’”32 That view changed by the time Frederick was king, for many a German lad found the most attractive aspect of the hussar’s role was his almost unique opportunity for plunder. It was the hussars who also had the role of pursuit in the wake of victory. That freedom of action out of sight of the high command, however, was one of the main fears of a king worried about desertions. The hussars had a more colorful uniform, somewhat Turkish in its aspect, as inherited from the Austrian light cavalry (Hungarians and Croats) who had inherited theirs in wars against the Ottoman Empire. They too carried a carbine but their sword was curved, again as a nod toward their Middle Eastern roots.

Although the new cavalrymen usually arrived with a modicum of horsemanship, much more had to be taught. Two years was the minimum training, during which “each man was instructed in the skills of riding and horsemanship until he was complete master of both himself and his mount in all situations. Only after the completion of this basic initiation was he taught how to fire his pistols and carbine from horseback and to fight from the saddle with the sabre.”33 The cavalry were trained to operate as efficiently and in as orderly a fashion as were the infantry. Frederick’s most basic advances came in the area of training, where systematic methods were employed to instruct the trooper in a variety of required drills, exercises, and maneuvers. He was also responsible for the introduction of revolutionary new cavalry tactics: the charge at the gallop, the charge in echelon, the charge in column, and maneuvering while moving, as well as the use of light cavalry in close-order fighting on the battlefield.34 Although each style of cavalry had its assigned role, they all trained to do each other’s jobs. All three types of Prussian horsemen received the same basic instruction so that their functions were quickly and easily interchangeable, so a cuirassier could when needed be a scout or a hussar could charge into battle. This flexibility was unique to the Prussians.35

Although the horsemen carried firearms, Frederick disallowed their use in almost all circumstances, and certainly during the charge. As time went by, Frederick became more wedded to the concept of speed equaling power, so the cavalry in their charge started their gallop at greater and greater ranges. According to Nosworthy, “In 1748, Frederick demanded that they charge 700 yards (trot: 300; gallop: 400). In 1750 this was increased to a total of 1200 yards (trot: 300; gallop: 400; and full speed: 500). This was increased to an incredible 1800 yards in 1755, with the last 600 yards at full speed.”36 All of this had to be done in formations almost as tight as those practiced by the infantry. Seydlitz, although somewhat lighter handed in disciplinary measures, still drove his men in daily practice and in peacetime army maneuvers. “The cavalryman’s equipment was made as light as possible to enhance speed and increase the fury of the charge,” writes Trevor Dupuy. “Close order and alignment were achieved by constant drill, and Prussian cavalry could move with the same precision and perfection as the infantry. Eight to ten thousand mounted men could charge for hundreds of yards in perfect order, then after a melee re-form for movement almost immediately.”37 Enemy infantry squares with bayonets (if they could be formed quickly) offered some defense, but they could maintain a line only against trotting horsemen. The galloping attack en muraille (as a wall) was key in most of Frederick’s victories.

Frederick was much more interested in the cavalry than he was in artillery, despite the rising prominence of the latter; however, he also brought the concept of speed to his artillery.38 Even though smaller and lighter cannon had been on the battlefield for some time, the Prussians made them even more mobile. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor Dupuy point out how “Frederick carried one step farther the artillery tactical developments of Gustavus Adolphus. He created the concept of the horse artillery (as opposed to conventional horse-drawn artillery) in which every cannoneer and ammunition handler was mounted, so that the light guns could keep up with the fast-moving, hard-riding Prussian cavalry.”39 The Prussian artillery arm, as in all the European armies, was manned by civilian contractors, engineers who were looked down upon by all other arms. In the days of Frederick William, General Christian von Linger oversaw the artillery and reduced the guns to four sizes: 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-pounders (determined by the weight of the cannon ball). The two smaller guns were assigned to the front lines with the infantry while the larger two were deployed farther to the rear and massed to focus on a particular section of the enemy army. The gun barrels alone weighed in at 988 and 1,800 pounds respectively, so rapid movement was not possible. The smaller guns, however, were moved about rapidly by three-horse and four-horse teams.

Improvements during Frederick’s reign came thanks to Lieutenant Colonel Ernst von Holzmann. He developed the caisson, a box carrying ammunition and powder added to the limber supporting the cannon’s trail. This allowed the gun and crew much more independence, able to operate further away from the battalion or regimental ammunition supply. Holzmann also introduced a better method for adjusting the gun’s elevation. The Austrians had developed a wedge placed under the rear of the cannon to be slid in and out to control elevation and depression. Holzmann added a screw mechanism to the wedge so it could be more finely adjusted. Most of the time all the guns fired solid round balls, which did damage to solid targets but also to individuals as the shot bounced through infantry lines “like a bowling ball gone berserk,”40 taking lives and removing body parts. For short-range work, however, Holzmann crafted the idea of employing canister rounds, cylinders of sheet metal or wood that enclosed scores of shot about the size of walnuts. The lightly built cylinder disintegrated as it left the muzzle, and the shot sprayed over a wide arc.41 Grapeshot was a variation on the canister, with larger shot. Frederick also came to appreciate the value of the howitzer, “a stubby, heavy-calibre chambered piece, specially designed to throw explosive shells without cracking the brittle cast iron of their casing.”42 The howitzer was traditionally a siege gun designed to lob cannonballs in a high arc over walls; Frederick began using the weapon on the battlefield to strike at hidden targets in dead ground behind the enemy. Most of these improvements, however, did not go into effect until the latter part of the Seven Years’ War.

ALTHOUGH THROUGHOUT HIS REIGN he shifted alliances when he deemed it necessary, Frederick’s primary opponent was Austria. Whereas his forebears had subordinated themselves to the emperor in Vienna, Frederick realized that to strengthen the security of his territory he needed extra land to fill in the gaps between his holdings. The most necessary land was Silesia, the pathway from Bohemia into Brandenburg. Although Brandenburg and Prussia were politically a single entity, in 1740 they were not joined physically; West Prussia (under Polish control) lay between them. Thus, Frederick’s overall goal was both defense and unification. With the death of Charles I in Vienna just a few months after Frederick came to power in 1740, the confused situation in Austria invited Frederick to begin his project. As Charles’s successor was his daughter, Maria Theresa, it was an open question how many European powers would recognize her as a legitimate ruler. Over the previous several years all the major powers had signed the Pragmatic Sanction agreeing to recognize a female successor, but just how many would come to the aid of potentially weak twenty-three-year-old queen? Frederick had demanded cession of the Duchy of Silesia as his price for honoring the agreement. The law there did not allow a female ruler, and he claimed a relation to the last duke of Silesia. Frederick seized the opportunity.

He was correct in assuming Austria was fragmented and unprepared for war. “He was wrong, however, in his assessment of the energy, strength and wisdom of the new Austrian ruler, by far the most distinguished monarch the Habsburgs ever produced, and in the fervent support she was to receive,” Albert Seaton asserts.43 The first assistance for Maria Theresa came from Hungary, a nation recently at odds with Austria but befriended by Maria Theresa’s father, Charles. A standing Hungarian force protecting the southern frontier from Turks provided 39,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry. Coupled with the existing Habsburg army, which had recent experience against the Turks, the Austrian resistance proved stronger than Frederick had anticipated. However, the Austrian infantry’s method of fighting was no different than that of any other country: linear warfare. The cavalry trotted forward in a line, then at twenty paces fired their pistols and spurred their horses. Neither had the discipline or speed of the Prussians. The Austrians’ edge was in their light troops with superior scouting and harassment abilities, but on the battlefield they used muskets and bayonets like all other European armies.

At first Frederick’s December 1740 invasion met little resistance, with the Prussian army occupying just about every city in Silesia before the Austrians could react. Frederick hoped that a fait accompli, followed by his reassurance of support for Maria Theresa’s claim to the remainder of Habsburg lands, would be sufficient to keep her from reacting. But, Ritter asserts, “[h]e did not know that this woman possessed more courage and a greater sense of honor than all the men at her court. That she had been robbed of Silesia without so much as a warning made it impossible for her to acquiesce. She would rather risk extreme peril than accept such an insult. In her person, Habsburg’s ancient imperial pride rose up against the faithless vassal.”44 It only got worse for Frederick, as the other countries he expected to move in and grab parts of the empire, such as France and some of the Germanic states, failed to do so. The diversions he expected never materialized, and Maria Theresa was able to focus her military efforts on him rather than on her western frontiers.

In the spring of 1741, an Austrian army under Field Marshal Wilhelm Count Neipperg marched out of Bohemia with the intention of severing Frederick’s army from its supply bases in Berlin. In desperation, Frederick marched north to avoid being cut off, but ran into the Austrian army at Mollwitz on 10 April.

Frederick had wanted to avoid such a situation. Earlier reports of Austrian forces in Bohemia motivated him to pull his forces back and together. On 29 March, however, he was convinced otherwise by his senior advisor Kurt Christoph Count von Schwerin, who believed that the better idea would be to keep the troops dispersed in order to maximize foraging. When Frederick concentrated his forces and began moving he had a numeric and qualitative edge: 21,600 Prussians to 19,000 Austrians, of whom 10,000 were infantry and most of those recruits. An infantry battle should certainly go Frederick’s way, but as he was deploying his forces early in the afternoon of 10 April his right wing was struck by an overpowering cavalry attack that not only sent the Prussian horse flying but threatened to crumple the entire army. Frederick himself was in imminent danger of being captured. “No one expected anything like it,” Ritter notes. “How long had it been since a Prussian ruler had personally fought in battle? The fate of Gustavus Adolphus and Charles XII may have flashed before the eyes of the Prussian generals, and the natural excitement of their young commander-in-chief probably interfered with their tactical dispositions.”45 Frederick took his senior commander’s advice and fled, with Austrian hussars hot on his heels. The remainder of the Austrian cavalry, however, re-formed and prepared to charge the Prussian lines. The years of discipline paid off; neither cavalry nor infantry could make headway against the immovable Prussian lines. The Austrians withdrew at dark, losing the battle but winning the campaign, for Frederick halted his invasion.

The young king wasted no time identifying mistakes and addressing them. He observed the strength of the infantry and the poor quality of the “damnably awful” cavalry. His own mistakes? He allowed the army to remained scattered when he should have concentrated it; he allowed himself to have his lines of supply cut; and he spent too much time deploying before the battle. Deciding to keep his army in camp at Mollwitz, Frederick immediately began making improvements. He depended on Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau and his sons to keep up the infantry training while he turned to the cavalry. He began to look to a hussar officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hans Joachim von Ziethen, whose “skill in light cavalry tactics was such that his hussars led the way for the total regeneration of the Prussian cavalry.”46

As Frederick worked on his army through the quiet summer of 1741, Bavaria, Saxony, and Savoy went to war against Austria. This obliged Maria Theresa secretly to promise to leave the Prussians in Silesia in return for a cease-fire, but she reneged on her promise within two months. In the spring of 1742 Prince Charles of Lorraine led an Austrian army against the Prussians. At the Battle of Chotusitz in mid-May, the Prussian cavalry initially gave a good account of themselves but were scattered by a counterattack while trying to re-form. On the Prussian left Prince Leopold held the village of Chotusitz in bitter fighting before he was finally forced back. During his withdrawal, Frederick, on Leopold’s right, brought his men out of a hollow where they had lain unobserved and launched them at the now-exposed Austrian flank. At this surprise, the Austrians broke and fled.

This defeat led to the Treaty of Breslau in mid-June (ratified in late July) whereby Maria Theresa ceded Silesia in return for an end to hostilities. Apparently, neither she nor Frederick really believed this would end the fighting for that province. However, as Theodore Dodge observed, “Frederick had learned good lessons. He had gained self-poise, and a knowledge of the hardships of war, the meannesses of courts, and the fact that he could trust no one but himself and his devoted legions. He was disenchanted. War was no longer glory, but a stern, cold, fact.”47

With some breathing space from his Austrian opponents, Frederick watched political events and worked on his army. For two years he built his treasury back up and expanded his forces to 140,000 men. He also introduced a new innovation: peacetime field maneuvers.48 In the meantime, Bavaria—a Prussian ally—had been losing continually to Austrian forces, and the pro-Austrian alliance grew larger when England joined the Dutch and several Germanic states to fight the French. In the summer of 1743 Frederick renewed Prussia’s alliance with France, which, under the leadership of Louis XV, was eager for some more glory. Hoping for a Franco-Prussian offensive into Austria, possibly even threatening Vienna, Frederick broke the Peace of Breslau and led his armies into Bohemia in August 1744.

The Prussians quickly captured Prague and continued south, but unfortunately for Frederick the French did not keep the Austrians busy. With sufficient allies to keep an eye on the less-than-aggressive French, the Austrians moved their army eastward to deal with Frederick. Everything went against him all at once: bad weather, breakdown of supply, harassment by the enemy’s light troops, epidemic. His generals thought he was going too far too fast, but they could not influence him. He finally took his army back to Silesia late in 1744 in bad shape, with at least 17,000 desertions along the way. “Totally demoralized, the proud army finally returned to Silesia,” Ritter observes. “Every weakness of troops trained to unquestioning obedience but incapable of independent action had been laid bare.”49 Indeed, the confidence the First Silesian War had given him took a major blow as well, and Frederick was learning to balance his own views with considered advice. He could not depend on subordinates alone, as he had at Mollwitz, but he could not ignore them as he had done on this campaign.

With Frederick’s army severely weakened and the ego of its leader bruised, Maria Theresa saw her opportunity to punish Prussia and regain Silesia, and in 1745 sent her army out of Bohemia under the command of Charles of Lorraine. He had overseen the recovery of Bohemia, but he had had the expert advice of the veteran field marshal Count Otto Ferdinand von Traun, who was now in command of forces facing France. Still, Maria Theresa thought him just the right man for the job. Reed Browning asserts, “What was needed in Silesia was not cunning or brilliance, but rather the conventional skills of a seasoned commander. These Prince Charles could muster—and he [as her brother-in-law] could bring too all the prestige that attaches to relationship to royalty.”50

CHARLES HAD A GOOD PLAN. With 55,000 Austrian and 20,000 Saxon troops at his disposal, he would put the bulk of his troops in Bohemia into a drive on the Silesian capital of Breslau, a secondary force would feint from Moravia to draw off some Prussian troops, and a screen of light troops would harass the Prussian supply lines. Charles also had spies alerting him on Prussian plans and movements. He confidently looked forward to finding a demoralized enemy whom he could sweep from the field.

The Prussian intelligence service, which was always one of Frederick’s primary weaknesses, outdid themselves this time, however. One of Charles’s spies was actually a double agent and Frederick took full advantage of him. Not only did Frederick know the Moravian force was a diversion, but he also used the spy to pass on the disinformation that he planned to withdraw toward Breslau, just as Charles already assumed. Frederick led Charles to believe that the Prussians would behave as they had done in 1744, retreat to the north to avoid being cut off from their supply base at Breslau. To strengthen this idea, he evacuated part of southeastern Silesia. In reality, Frederick intended to go on the offensive with 70,000 men as soon as the Austrians could be lured down to the plains of Silesia.51

When Austrian forces crossed the mountains from Bohemia into Silesia at the beginning of June 1745, they met no resistance. That Frederick would not contest the passes further confirmed the Austrian notion that the Prussians would not fight anytime soon. Thus, when the army debouched onto a plain facing east toward the Striegauer River and the town of Striegau52 (their goal for the following day), they made no particular effort to secure their perimeter. After all, the Prussians were miles away and the Austrian troops were tired from their strenuous climb. The 19,000 Saxons encamped on high ground near Pilgrimshain, and the lines stretched roughly south-southwest to Günthersdorf, with the 40,000 Austrians deployed down to Thomaswaldau, then southeast to Halbendorf.

Frederick had observed the Austrian positions firsthand. He endeavored to do this before all his battles in order to exercise what he termed coup d’oeil. “The coup d’oeil of a general is the talent which great men have of conceiving in a moment all the advantages of the terrain and the use that they can make of it with their army,” Frederick wrote. “The coup d’oeil is required of the general when the enemy is found in position and must be attacked. Whoever has the best coup d’oeil will perceive at first glance the weak spot of the enemy and attack him there.”53 In this case, Frederick decided to hit the Saxons on the high ground first, then drive south into the Austrians. The 59,000-man Prussian army began a night march in complete quiet. The normally active Austrian Croat light cavalry were not on patrol. The Austrians were blissfully ignorant of the approach, Frederick’s double agent having assured Charles that the Prussians were not within striking distance. The Prussian forces reached the Striegau at midnight, caught their breath for a couple of hours, and then moved across the stream and onto the plain. Duffy describes the Prussian plan: “The columns were to pass the Striegauer-Wasser in the region of Striegau, Gräben and Teichau and make northwards in the general direction of Pilgrimshain until they had covered enough ground to be able to form a line of battle. The Prussians were then to advance to the west, with the right leading in a staggered echelon of brigades.”54 The cavalry was primarily deployed on the right and it was their mission to hit the Saxons at dawn to start the battle. The infantry for the most part faced the Austrians, intending to launch their attack as the Saxon wing crumbled.

First contact came at 4:00 a.m. when leading elements of the Prussian cavalry stumbled into some Saxon grenadiers on the Breite Berg, a hill between Striegau and Pilgrimshain. The Saxons quickly fled, leaving the Prussians with good ground for artillery. Rather than allow the retreating grenadiers to rouse the defense, the Prussian cavalry pressed the attack. The Prussian cuirassiers found themselves facing stiff resistance and called for support from the dragoons and hussars, who were glad to assist, “and within a few minutes dragoons, hussars, cuirassiers and enemy mounted grenadiers were engaged in a deadly hand-to-hand combat, swirling about like a swarm of bees.”55 After two charges the Saxon cavalry broke, but they had bought some time for the infantry to form up. Meanwhile, Prince Leopold Max was bringing twenty-one Prussian infantry battalions directly from the line of march into attack formation. Under Frederick’s philosophy that cold steel was more important than firepower, the Prussians advanced with shouldered muskets, through intense musket and artillery fire, until they saw the whites of the Austrians’ eyes. The Prussian attack did not break the Saxon infantry immediately. Not until 7:00 a.m. did they abandon the field.56 Frederick supposedly told his men to show the Saxons no quarter, “an order thoroughly congenial to troops now possessed by what one of them called a ‘demonic bloodlust.’”57

The Saxons received no assistance from the Austrians, slowly emerging from their tents. Prince Charles had heard the firing and assumed it was the Saxon assault on Striegau. Not until retreating Saxons approached his headquarters did he learn differently. Charles ordered his cavalry on his far right flank into the battle, but they were engaged immediately by Prussian cavalry so could not aid the Saxons. The cavalry battle on the southern end of the battlefield swayed back and forth. A dozen Prussian cuirassier squadrons found themselves cut off from the rest of the army when a bridge across the river collapsed, but quick action by Ziethen’s hussars finding and crossing a ford saved the day. The Prussians finally gained the upper hand and the Austrian cavalry broke. “By 7:00 a.m. the Prussian situation was truly enviable,” Browning notes; “they had shattered the allied cavalry on both wings and had put the Saxon infantry to flight. Only the Austrian infantry still contested the field, stripped of its ally and exposed as never before in the war.”58

The Austrian infantry bravely stood in their lines and exchanged volleys with the Prussians. As the Prussians advanced, a gap appeared in the middle of their infantry. Following along behind the infantry all morning was a Prussian cavalry unit, the Bayreuth dragoon regiment. Seeing the widening gap and fearful that a counterattack might exploit it, they exploited it themselves. Over a fairly short distance they broke into a trot and then quickly into a gallop through their own lines and into unsupported Austrian infantry. A quick volley was all the Austrians could loose before the horsemen were in their midst. Dennis Showalter describes the result: “In less than half an hour the Bayreuth Dragoons took no fewer than sixty-seven colors—a far greater tribute to the force of their charge than the five guns that could not be withdrawn, or the 2,500 prisoners who compared their maximum foot speed to the pace of a running horse and sensibly threw down their arms.”59

That, for all intents and purposes, marked the end of the battle as the rest of the Austrians either fled or surrendered. The battle was over by 9:00 and no serious pursuit was launched, for the Prussian infantry had no more strength and the cavalry could not be quickly re-formed. The casualty count uncharacteristically favored the Prussians, who lost some 900 dead and 3,800 wounded; the Austro-Saxon dead numbered more than 3,000 and the wounded some 10,700.

The success at Hohenfriedberg came about as a result of Frederick’s approach march followed by a deliberate attack. There was little exploitation or immediate pursuit, owing to his ongoing fear of desertion; indeed, so ingrained was the order against breaking their lines that the Prussian troops cleared the field of enemy forces without a man engaging in a single act of looting. Frederick fulfilled all the characteristics of the offense in this battle. He gained surprise through both disinformation and the secretive night march. He hoped to implement the oblique order in this battle, with stronger forces on his left facing the Austrians while the cavalry and fewer infantry struck the Saxons on the left flank with the intent of a “swinging gate” movement onto the Austrian position. He was in control of the tempo of battle, even though the enemy infantry put up stout defenses. Had he used his firepower on the advance this probably would have been even more to his advantage. Although the two armies had roughly equal numbers, Frederick showed his audacity by acting completely against the expectations of his foes; by not pausing at any point but quickly reacting to changes on the field, he gave the defenders no opportunity to do anything but defend.

Hohenfriedberg was Frederick’s most impressive victory thus far.60 Frederick here showed that he was rapidly transforming himself into a great general. He had learned from his mistakes in previous battles and began showing the characteristics for which he would be best known. The oblique order may or may not have been attempted here; if he intended to use it the deployment in the dark surely hampered it. Further, with the quick movement of infantry marching toward the fighting being redirected toward the Austrians, as other units were deploying in the southern area, implementing the oblique certainly would have been a challenge on the parade ground, much less on the battlefield.

In the wake of the battle the Austrian survivors quickly re-formed and conducted a safe withdrawal back across the mountains, with the Prussians close behind. For the next three months Frederick’s goal was to feed off Bohemian crops for his troops and fodder for his horses. This would lessen the demands on his logistics as well as deny those same supplies to the Austrians should they try to reenter Silesia. Frederick’s army skirted the western side of the mountains up to the Elbe, with the Austrian force following slowly along behind. Hohenfriedberg had not disheartened the Austrians; indeed, Maria Theresa’s husband, Prince Francis, was elected Holy Roman emperor. Frederick, as elector of Brandenburg, voted against him, but promised his support in return for (not surprisingly) full claim to Silesia. Maria Theresa was still not ready to agree, so her armies tried one last time to defeat Frederick and drive the Prussians away. Charles stole a march on Frederick in September 1745 and placed himself once again athwart the Prussian lines of communication.

At first glance, what became the Battle of Soor (Sohr) was Hohen-friedberg in reverse. The Austrians staged a night march through heavily wooded terrain, emerging before dawn and seizing high ground overlooking the Prussian camp. Frederick was overconfident of the enemy’s lack of resolve and laid his camp out without paying attention to security. In particular, he neglected to occupy or even place guards on the high ground to the Prussians’ right, which was the route of his line of march back to Silesia.61 The Austrians, outnumbering Frederick’s 22,000 by two-to-one, were poised to strike a killing blow but held their hand. Charles would not attack into the early morning fog and mist, and that gave Frederick’s quickly reacting troops time to deploy. Frederick threw a cavalry attack around the far right flank of the hill atop which the mass of the Austrian force was located. The Austrian cavalry stood still, firing at long range, when Frederick’s cavalry emerged from a narrow valley and attacked uphill against a force twice their size. They succeeded in seizing the hilltop as Prussian infantry attacked from the opposite side. The rest of the army advanced all along the line, and the Austrians soon were retreating back into the woods. The Prussian discipline and drill of so many days and months in camp proved the deciding factor as the Austrians failed to take advantage of their opportunities. “From this day on dated [Frederick’s] European reputation as a military leader, and the belief in his invincibility,” remarks Ritter.62

A few other minor battles took place through November into December, with Frederick’s hussars doing good work in harassing the Austrians and seizing supplies. As the year came to a close, Maria Theresa had had enough for the time being. On 25 December she signed the Treaty of Dresden, in which she accepted Frederick’s recognition of Francis as Holy Roman Emperor in return for ceding Silesia. Frederick went back to training and drilling his army.63

Fighting between Austria and France continued for some time after Prussia left the war, but Frederick was intent on getting his army back up to strength and preparing for whatever future conflicts might arise. He had no illusions about the permanency of Austria’s cession of Silesia. He also saw the rising hostile power of Russia as a threat he would sooner or later have to face and recognized that the Prussian army would have to adapt in order to do so successfully. In the decade after Silesia’s acquisition Frederick wrote his directives on warfare, known today as The Instruction of Frederick the Great for His Generals, finished in 1747. It was revised in 1748 under the title of General Principles of War. A confidential set of instructions and meditations on war, one copy was sent in 1748 to Frederick’s successor with a request that it should be shown to no one. In January 1753, an edition of fifty copies was printed and sent to a list of his most trusted officers. Frederick ordered each recipient on his oath not to take it with him in the field, and should the officer die arrangements should be made to have the book returned whole and unharmed.64 In the book, Frederick advocated principles he saw as necessary for successfully conducting a campaign. The book’s first chapter addressed the Prussian army’s main problem, keeping soldiers from deserting. There followed chapters on planning for a campaign, reading enemy intentions, conducting the campaign, and conducting a battle, including his oblique order. Duffy summarizes some of the elements covered: “In the final articles, Frederick dealt interestingly with the element of chance in warfare, the evils of councils of war, and the cost of a winter campaign, returning in Article XXIX to his new battle tactics, a system ‘founded on the speed of every movement and the necessity of being on the attack.’”65

In his personal life, Frederick became famous for his work ethic, rising at 4:00 a.m. to work on matters of state. After a modest lunch he would study and work on his musical skills until evening, finish up more paperwork after supper and retire at 10:00. He built his army up to 150,000 men and maintained the vaunted Prussian training and discipline. The number of cannons doubled, and the cavalry expanded almost as much. He also instituted war-gaming maneuvers in the field to observe and perfect his oblique attack. “In a comprehensive test of overall readiness, Frederick assembled the Army once a year for maneuvers,” write A. S. Britt and colleagues. “The generals, as well as the troops, demonstrated their proficiency. Marches, tactics, logistics, and new equipment were subjected to the King’s scrutiny. Every detail went through his exacting inspection.”66 Two of his generals on their own initiative began experimenting with all-arms divisions. Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick developed a concept of marching in four separated all-arms columns; although it was never perfected in Prussia, it would enjoy major success when redeveloped by Napoleon.67 Frederick also refilled his treasury. All these exercises proved necessary when, by 1756, his enemies had massed against him.

Meanwhile, spurred by the embarrassment of losing Silesia, Maria Theresa began improving her military, introducing drill and discipline in the style of the Prussian army and upgrading artillery. General Leopold von Daun oversaw a commission to implement Prussian-style tactics and write new regulations, as well as implement summer maneuvers as Frederick had done. Her army expanded to 200,000, but the improvements were just beginning when the next war arrived. In spite of their numbers, plus that of the allied armies that would soon join in, Austria wisely adopted an overall defensive strategy that would play on its major strength over the Prussians: their light troops. As Daniel Marston recounts, “These troops, also referred to as Croates and Pandours by contemporaries, were made up of soldiers from the Balkan frontier regions. … The Austrians used this military corps as light troops, employing them to reconnoiter, forage, and skirmish. They were deployed on the flanks of the army as it marched, and would report on the movements and dispositions of the Prussians before battle. During battle, they would attack the flanks of the Prussian lines, trying to get them to fire and break ranks.”68

As was often the case in European history, peace was merely a temporary break in the action between wars. Grudges from the War of the Austrian Succession still festered, but new alliances were necessary to gain revenge or protect possessions. The only constant was the Anglo-French hostility, primarily played out in North America with sideshows in India and the Caribbean. Maria Therese wanted to regain Silesia and, if possible, reduce Prussia to the minor state it traditionally had been. Frederick’s goal was to hold on to the gains from the last war and, if possible, conquer Saxony. The Russians were afraid of Prussian desires along the Polish frontier, which they were interested in conquering.69 To achieve their goals, or to watch each other’s backs, Austria allied itself with Russia. Fearful of this powerful new alliance, Frederick concluded an alliance of his own with Britain, whose primary Continental concern was the German state of Hanover, home of the new English royal family since George I’s accession in 1714. This Treaty of Westminster, completed in January 1756, so outraged the French that after their ten-year alliance agreement with Prussia lapsed in 1757, they formally joined the Austro-Russian alliance, along with Sweden and Saxony. Haythornthwaite points out that “[i]t was an alliance in which all except France had designs on Prussian territory, designs which if successful would have reduced Prussia once again to a minor principality.”70 As Russell Weigley observes, other powers in Europe ganged up on Prussia as they would Germany almost two centuries later, fighting against a state aiming at military dominance.71

With Austria and Russia both focused on him, Frederick decided on a preemptive strike against Saxony. In late August 1756 he marched 63,000 men (less than half his army) into Saxon territory. The Saxon army numbered a mere 18,000, and it quickly withdrew into a strong defensive position at Pirna. Frederick’s goal had been to make quick work of Saxony, then use the Elbe River valley to advance into Bohemia. He had no time for a siege if he was to strike Bohemia while Austrian forces were still dispersed, so he left a covering force at Pirna and marched south. The Austrians responded by sending a relief force under Irish immigrant Maximilian Browne, who encountered the Prussians at the Eger River.

After a week of skirmishing, Frederick staged a flank march on the Austrian camp at Lobositz. He launched a cavalry assault in the early morning fog and saw it repulsed, as was a second. Improved Austrian artillery took its toll against both cavalry and infantry when Frederick committed them, but finally superior Prussian discipline broke the Austrian line. The Austrian troops withdrew in good order under artillery covering fire. Both sides started with roughly 30,000 men and ended the day with roughly 3,000 casualties. The Austrians demonstrated their improved training, but Frederick held the field. The besieged Saxons in Pirna soon surrendered, and Frederick achieved his first goal as the fighting season of 1756 came to an end: Saxony was his. He relieved all the Saxon officers but forced the remaining soldiers into the Prussian army. This proved an unwise move since he did not scatter them throughout his own units but left them in their existing Saxon contingents. These units deserted wholesale whenever the opportunity arose.

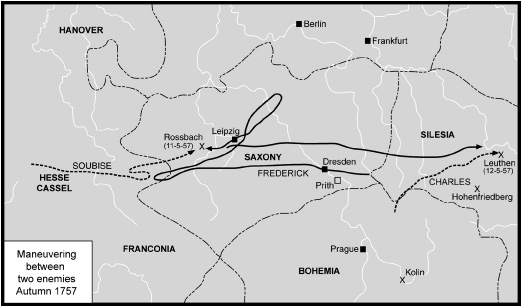

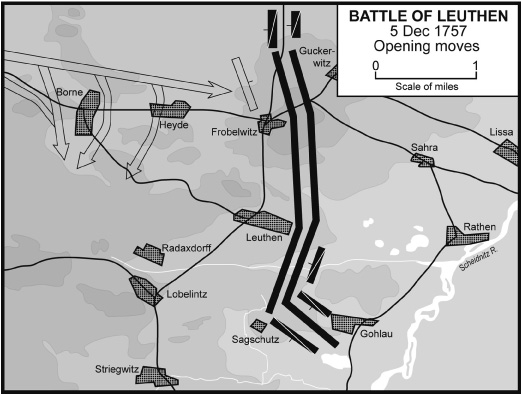

Frederick got off to a strong start the following year. In the spring of 1757 the Prussian army streamed into Bohemia in four columns, converging against the Austrian army just to the east of Prague. Although in a strong position, the Austrians left a gap in their center as they attempted to reinforce against the Prussian cavalry pressing their right flank. Frederick took advantage of the opportunity and won a solid victory. Duffy summarizes the state of affairs afterward: “Thus Frederick had taken on an Austrian force of approximately equal size and had driven it from its prepared position in the face of almost every conceivable obstacle and accident. … At the same time the Prussians had plenty of food for thought. They had lost over 14,000 men (actually more than the Austrians) and among that number were included Field-Marshal v. Schwerin and what Frederick called ‘the pillars of the Prussian infantry.’”72 The victory was not long celebrated. The remains of the Austrian army withdrew into Prague, forcing Frederick to lay siege; only a month later, a relief army under Leopold von Daun arrived and dealt Frederick a serious defeat at Kolin in mid-June, forcing the Prussian army back into Silesia. Six weeks later a French army overcame a force of Germans protecting Hanover, and by early September they controlled the province. This gave France an open road into Saxony. To make matters worse, at the end of August a Russian invasion through Poland into East Prussia gained a quick victory over Frederick’s holding force there. Luckily for Frederick the Russians pulled back into Poland for the winter, but he still had serious French and Austrian threats to deal with.

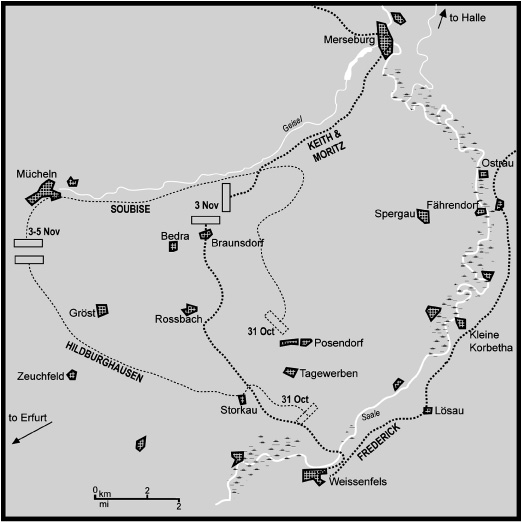

FREDERICK WAS LUCKY that Austrian marshal von Daun was overly cautious and did not seize the momentum after the battle at Kolin to press the Prussians completely out of Bohemia. Temporarily saved in the east by the Russian withdrawal and aided in the south by Daun’s lack of vigor, Frederick decided to strike westward against the encroaching French, who, having taking Hanover, now threatened Saxony. The French army was initially under the command of General Charles de Rohan, Prince of Soubise. It was reinforced by a coalition army of German imperial states loyal to Maria Theresa under the nominal command of Field Marshal Prince Joseph Friedrich von Sachsen-Hildburghausen. The command was nominal because it was a coalition: 231 states contributed troops, and Hildburghausen soon learned that the term “chain of command” meant little when so many generals and princes were in the army with their own ideas of how things should be done.73 The command structure was further weakened by the soldiers they commanded. The quality of the French soldier had deteriorated badly in the decade since the War of the Austrian Succession, and French officers were often dandies who had no concept of discipline. A French officer captured after Rossbach described his army as “a traveling whorehouse.” Hildburghausen’s so-called Reichsarmee thus lacked any coordination. Showalter points out that though in previous wars “Imperial troops had performed well as part of larger entities once they learned their trade, [i]n 1757, … they were being sent against the best fighting army in Europe with less than six months’ experience in working together, with supply and administrative services even weaker and more disorganized than those of France.”74

Thus, attacking through Saxony certainly seemed the wisest choice. Leaving General A. W. Bevern with 36,000 men to protect Silesia from an Austrian offensive out of Bohemia, Frederick led 10,000 men to Dresden. There he combined his force with 12,000 men under Maurice (Moritz) of Dessau. Together they marched westward past Leipzig to Erfurt in far western Saxony, arriving on 13 September. Soubise, not yet joined by Hildburghausen, abandoned the town and relocated southwestward to Gotha. For the next four weeks the two armies crossed and recrossed the same ground, reacting to each others’ moves. Not until mid-October was there a major move, when 3,400 Austrian Pandours launched a surprise attack on Berlin. Not knowing how large the force was, Frederick took 14,000 men to relieve the city as the rest of his force pulled back east of the Saale. That convinced the Franco-German commanders to advance. They were bluffed out of their offensive by Frederick’s new commander of cavalry, thirty-six-year-old Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz. Seydlitz used his cavalry so aggressively at Gotha that Soubise was convinced the entire Prussian army was at hand. Fredrick was quickly back in Saxony with his main force by the 28th after he learned that the attack on Berlin had been no more than a raid. Hildburghausen, however, had advanced again east across the Saale River, and Frederick hoped to catch the imperial forces on the move. He broke his force into three prongs to cross the river at Merseburg, Halle, and Weissenfels. Unfortunately, when he reached the town of Wiessenfels the imperial troops retreated and burned the bridge behind them. Hildburghausen withdrew toward Erfurt. Soubise had considered opposing Prussian crossings at the two other towns after burning the bridges there as well, but pulled back to Müchelin, where he was joined by Hildburghausen. Together they numbered some 42,000 troops (though Friedrich estimated them at 60,000).75 The initial French deployment was on the Schatau Heights in an east-west line, but Hildburghausen convinced Soubise to swing ninety degrees and face east with a north-south line.

Frederick’s three prongs converged on the town of Braunsdorf early in the evening of 3 November. He had roughly 22,000 men, whom he deployed along a line anchored on the north by the village of Bedra and on the south by Rossbach. Forces probing the French position early had withdrawn in the face of intense artillery fire, so Frederick decided to await developments rather than charge uphill against superior numbers. Fortunately for Frederick, Soubise thought that the repulse had cowed the Prussian king. Finally, Soubise got up the courage to launch an attack, which his staff and Hildburghausen had been pressing. The two allied commanders decided to abandon their high ground and swing east by the Prussian left flank. Soubise wanted to hit the flank but Hildburghausen preferred a sweep behind the Prussians to threaten their lines of communication. This would force them to retreat back across the Saale or meet on open ground.

Why would the allies not stay in their virtually impregnable position? Primarily it was a matter of supply. Recent French reinforcements had arrived with no food of their own, straining the resources of an army that had been living off the land. Had the Prussians not arrived, Hildburghausen had been planning on withdrawing farther west to a supply base at Unstrut. The allied force had to move or starve. It was November and by that time of year most armies were already in winter quarters.

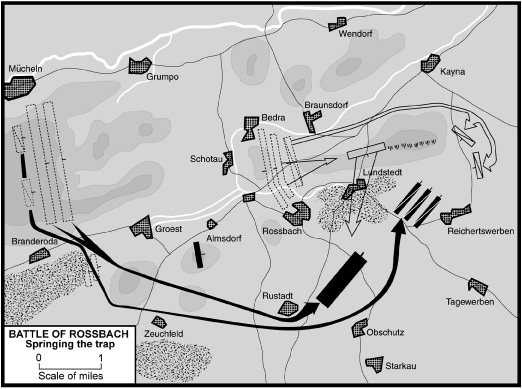

Further disagreements between the two commanders used up most of the morning of 5 November, and it was approaching noon by the time camp broke and the allies deployed for the march in three columns of infantry. Frederick assumed that their desperate supply situation was forcing them to move toward their base, and ordered his men to stand firm and wait. He posted a lookout to keep an eye on them while he sat down to eat. Seydlitz, however, thought the allies were maneuvering for an attack, so he ordered his cavalry to prepare for action. He was proven correct when the lookout informed Frederick that the French had turned east with the cavalry moving ahead as the infantry in three lines dragged along, losing their marching order as they made the eastward turn. The king was quick to act when he realized his position. At 2:15 p.m. the Prussian camp disappeared, in a matter of a few minutes, as the army faced about. Frederick ordered Seydlitz to lead the 4,000 cavalry eastward behind the cover of Janus Hill and position himself at its far end. The artillery, which had begun to prepare when the cavalry did, were quick to move as well. They were sent to the top of Janus Hill where they commanded an unobstructed field of fire as the enemy marched by. The infantry deployed between Ross-bach and the hill, hidden behind some woods.

The quick Prussian movement had not gone unobserved by French lookouts on a rise overlooking the village of Almdorf, about a mile west of Rossbach. Hildburghausen and Soubise jumped to the conclusion that their movement had accomplished its goal of forcing Frederick into a retreat. Not wanting to let him get across the Saale, the cavalry picked up their pace to get ahead of the “retreat.”

Within an hour of the Prussian move eighteen artillery pieces were atop Janus Hill. Showalter describes the initial action: “At 3:15 the process of [allied] disillusion began when the Prussian heavy guns opened fire. They did some damage, but not enough to halt the allied advance. Instead, the allied horsemen quickened their forward pace, accepting some disorganization as a fair price for getting out of the artillery’s killing zone.”76 The gunfire was the signal for Seydlitz to attack. While the allied cavalry hurried forward in line of march, Seydlitz came around the corner of Janus Hill with his cavalry spread out in attack formation. Frederick’s main biographer, Thomas Carlyle, observes: “‘Got the flank of them, sure enough!’—and without waiting signal or further orders, every instant being precious, rapidly forms himself; and plunges down on these poor people. ‘Compact as a wall, and with an incredible velocity,’ says one of them.”77 Although outnumbered by the allies 57 squadrons to 38, the Prussian cavalry’s initiative carried the day. The Austrian units in the lead slowed the charge only momentarily. Soubise joined the fray with another 16 squadrons of French cavalry to try to halt the retreat. However, it made little difference as Seydlitz committed the 18 squadrons of his second line. These units crashed into the allies in an attack around both flanks. Within half an hour the allied cavalry were being forced back and ultimately off the field of action.78 Seydlitz, wounded, led a hot pursuit as the allied cavalry fled at top speed.

Meanwhile, the lagging allied infantry advanced toward the Prussian artillery’s kill zone. As Seydlitz had mounted his charge the Prussian infantry had emerged from the woods. The Prussians had had time to deploy in oblique order with the mass of troops on the left flank to swing around the head of the French column.79 The units in echelon marched across the allied front, but then deployed in an unusual manner, which Showalter describes: “Instead of the familiar two straight lines of battalions, Frederick used his second line to extend the left flank of the first, forming an obtuse angle. This was done at a certain risk, since the final Prussian formation provided no significant reserves to plug gaps or cope with surprise tactical threats.”80

Indeed, there was a potential tactical threat from the French, who were experimenting with the concept of attacking in column, foreshadowing the tactics of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic armies. Two things kept the French from success: the typical Prussian fire discipline and the surprising reemergence of Seydlitz. In too many battles throughout history pursuing cavalry have taken themselves out of a battle in the thrill of the chase. Seydlitz broke with that unfortunate tradition and rallied his horsemen once the allied cavalry were safely out of the way. The returning cavalry struck as the Prussian infantry was delivering its normal devastating fire. Joined with the artillery barrage from on high and the sight of their cavalry broken and in flight, the allied infantry could stand no more demoralization. Carlyle comments: “French and Imperials throw weapons to the ground, run south from battle. Only two Swiss regiments retire in order. The Prussians pursue to Obschütz, taking numerous prisoners and most of the baggage. Darkness alone saves the enemy, who are in frantic flight south to Freiberg and beyond. The Prussians continue the pursuit, but it is dark and the men are tired. Frederick halts the infantry just east of Obschütz.”81

Allied casualties were 3,000 killed and wounded, with 3,000 to 5,000 taken prisoner. The Prussians lost around 550, mostly among the cavalry since no more than seven Prussian battalions had actually been able to fire their guns before the allies broke. Carlyle ranks the battle high in military history: “Seldom, almost never, not even at Crecy or Poictiers, was any Army better beaten. And truly, we must say, seldom did any better deserve it, so far as the Chief Parties went.”82

Since both armies were on the offensive; the allies used an approach march to stop what they assumed was a Prussian withdrawal, while the Prussians launched an attack that could be described both as hasty (“minimal preparations to destroy the enemy”) and as a spoiling attack (to disrupt an expected enemy attack, striking while the enemy is most vulnerable). Frederick benefited from the allies’ shortcomings: disagreement between commanders, lack of reconnaissance, disorganization on the march, and failure to coordinate infantry and cavalry. This should not, however, take away from his brilliance in grasping the value of the terrain while creating a plan and deploying his troops virtually on the fly. He exercised all the characteristics of the offense: surprise from all three arms; concentrating his cavalry to scatter superior numbers while his infantry did the same; dictating the tempo, though the battle was so short there was no real opportunity to alter it; and audacity, by attacking an army twice his size and not deploying in standard fashion but inventing his single-line infantry deployment on the spot. Seydlitz was the key to both the beginning and ending of the victory, arriving just in time to throw into headlong flight an army that was wavering from concentrated artillery and infantry fire. Like the Prussians, most of the allied army saw no action since only the lead elements engaged. Seydlitz successfully exploited the break but Frederick stopped any serious pursuit, as was his general practice. “Rossbach was an odd encounter. The standard patterns did not hold true. It was a contest between an agile army with brains and a clumsy army without any.”83

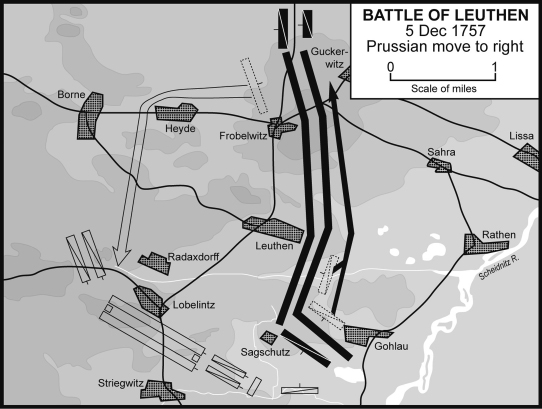

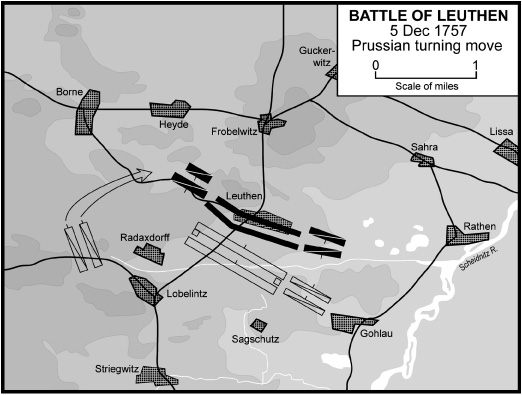

Although virtual destruction could have resulted from a hard pursuit, Frederick needed his army whole. One threat was negated, but the Austrians were still active, and he needed to shift both his focus and his troops as quickly as possible. “Rossbach was at least as much an Imperial as a French defeat,” Weigley notes, “but the lost battle proved to abate considerably such enthusiasm as the French had been able to generate for their unaccustomed alliance with the Habsburgs. Frederick had by no means swum out from his sea of troubles, but he could comfort himself that the shore might be in sight.”84 First, however, he had to swim to the opposite shore to salvage the situation in Silesia.