My experience facilitating Lean Coffees since 2012 has led me to develop a decent plan of action for getting them going within your team or organization.

My experience facilitating Lean Coffees since 2012 has led me to develop a decent plan of action for getting them going within your team or organization.

Friction around priorities and practices happens on the way to improvement.

—Scott Nasello

3.4

THE ART OF THE MEETING

Wednesday, Seattle, 9:00 a.m.

Nine people sip coffee around a table at a South Lake Union coffee shop in Seattle. All eyes are on Carmen, who is making a point about the impact of the latest round of layoffs at his company. The group is discussing how reorganizations impact different teams. People politely wait for Carmen to finish his sentence before voicing their opinion. A minute later, a timer goes off, and after a simple vote from everyone at the table, the subject changes to the next visually queued up topic written on a sticky note, “How to influence leadership.”

This is Lean Coffee—a structured meeting with few rules. Participants gather, build an agenda, and begin talking.

Created by Jim Benson and Jeremy Lightsmith in 2009, Lean Coffee emerged as one of the greatest ways a group of people can discuss ideas.1 The conversations are productive because the agenda for the meeting is democratically generated. People are engaged because they get to talk about topics that matter to them. Lean Coffee works because attendees are in charge of the agenda and everyone’s voice is heard. The minimal rules combined with mutual respect for each other provides a setting that encourages open dialogue and collaboration. Adam Yuret, who wrote How to Have Great Meetings: A Lean Coffee Book, says,

Lean Coffee turns traditional, one-direction management meetings on its head by helping teams uncover the most important topics to the majority of people, by allowing everyone to hear and to be heard, and by providing real-time feedback.2

I will add to that by saying that Lean Coffee doesn’t just change the tone of team meetings, it shifts the overall culture within the enterprise using it.

Reversing conditions where time thieves thrive requires change. Many of the problems related to time thievery have to do with organizational problems or company culture. To put it another way, when the company has a culture that is focused on keeping people busy (instead of on keeping work flowing), it invariably results in overloading people with too much WIP. This is not a productive culture. We want to avoid the mistake of having a goal to keep people busy all the time when the goal should be to generate value for the business.

In order for change to occur, people’s behaviors must change, and in order to change behavior, the hearts and minds of people must be open to change. Casual, in-person conversations with someone with an opposing viewpoint is one of the easiest paths to changing someone’s mind. Nothing accomplishes this better than a personal relationship generated by face-to-face conversation in a safe, calm, and respectful setting such as Lean Coffee.

How to Lean Coffee

My experience facilitating Lean Coffees since 2012 has led me to develop a decent plan of action for getting them going within your team or organization.

My experience facilitating Lean Coffees since 2012 has led me to develop a decent plan of action for getting them going within your team or organization.

First, block off sixty to ninety minutes.

Next, gather up sticky notes and markers and place them around a table. Once everyone is seated, review the Lean Coffee rules: only one person speaks at a time, and participants should attempt to listen more than they talk.

Then, invite participants to take just two to three minutes and use the provided materials to jot down as many topics as they would like, but instruct them to write only one topic per sticky note (sticky notes are our friends!). After everyone is done writing, participants should briefly (two sentences are usually sufficient) summarize their own topic(s) for the group so others can understand what they are voting on. Each participant gets two votes. It’s okay to vote on your own topic(s). It’s okay to use both votes on a single topic or distribute them across two different topics.

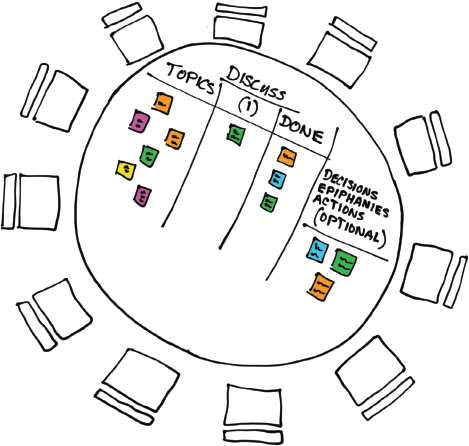

Tally the votes to prioritize the topics. Then, run the topics through a kanban board right on top of the table. Three columns are essential: To Discuss, Discuss, and Done. Place the topic with the highest number of votes in the Discuss column, and sort the others in priority order in the To Discuss column. If you wish, you may create a fourth column for decisions, epiphanies, or actions.

Set a timer for five minutes and invite the author of the topic in the Discuss column to lead off the discussion. The facilitator should take care to ensure everyone has a chance to speak. (Beware the loud extrovert monopolizing the conversation!) When the alarm goes off, allow the speaker to finish their current sentence, then vote using thumbs up or down. A majority of thumbs-up votes means the discussion may continue for additional minutes. A majority of thumbs down votes signals the group to move on to the next topic. The facilitator can break any ties.

Repeat this process until the Lean Coffee session ends. Lean Coffee concludes with a round of closing comments from each participant. It’s okay to pass.

Figure 49. Lean Coffee Setup

While Lean Coffee usually occurs with just a small group of people, don’t be constrained by group size. I’ve facilitated Lean Coffees with fifteen to twenty tables of ten people each.

Stand-Ups

Earlier, I described stand-ups that saw more foot shuffling than discussion, where project managers tried unsuccessfully to get status from attendees. A ceremony where you go around the room and everyone says what they’re working on today, what they did yesterday, and what they plan on doing tomorrow is a status meeting, which is unnecessary when work is visible on a board. It’s also boring. When we go around the room, people spend the time figuring out what to say when it’s their turn instead of giving others their full attention.

When the stand-up is done in front of a visual board, it is obvious what people are working on. When it comes to the stand-up, get to the point. Is there anything blocked? Is there any invisible work? Is there something we should know about? Something that will impact us? Something that should be on the board, but it isn’t? Make it snappy, and get to the after stand-up, where real problems get solved.

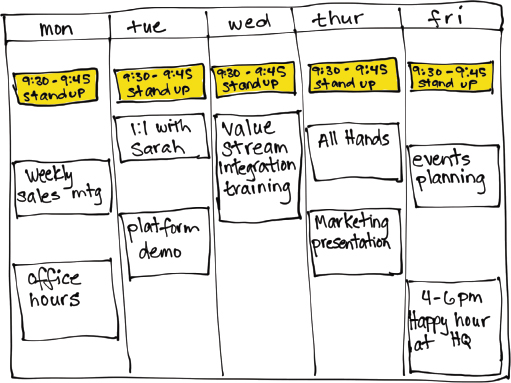

At one company I worked at, a group of thirty-five people met daily at 9:30 a.m. for stand-ups. Initially, the “go around the room” process was used. Some people were so uncomfortable speaking in the spotlight that their voices were mere whispers. Other people enjoyed being in the limelight and tended to hog a lot of precious and expensive time. Imagine the cost of thirty-five engineers and managers being in an ineffective meeting, not to mention that listening to thirty-five people report their status made for a dreadfully boring meeting. So, the meeting rules changed. Instead of going around the room, we set a policy that the board must be updated and accurate prior to 9:00 a.m. This allowed people to simply look at the board to see the latest status, and the stand-up could be spent focusing on risk and uncertainty.

The following three questions became the new agenda:

This change allowed the team to immediately see and recognize major blockers preventing important work from being delivered. The three questions made the stand-up simple and fast. It was over by 9:45 a.m. (just fifteen minutes), and this allowed an amazing thing to happen that was completely unexpected and spontaneous. Engineers hung around after the stand-up (because they had fifteen minutes free before heading off to their next meeting) and started to tackle some of the engineering problems that blocked work. We called this time the “after stand-up.” Previously, I would have had to schedule a meeting eight days out in order to find available time on the engineers’ calendars and to find an available meeting room (meeting room real estate was in high demand, and people frequently had to go to the coffee shop around the corner to meet).

The result was that meetings decreased because people hung around afterwards to solve the problems that had just been discussed. Half past the hour is a good time to schedule a fifteen minute stand-up because when it’s over, people will have fifteen minutes before they have to get to their next meeting.

Interruptions also decreased because instead of people popping in and interrupting me with “Got five minutes?” they knew that they could catch me at after the stand-up to ask timely questions or get quick feedback.

The stand-up together with the after stand-up allowed us to reveal where the time thieves were at work, which in turn saved much time from being stolen.

One last comment on the topic of meetings is the acknowledgment that the regular cadence of a meeting held at the same time, in the same location is extremely helpful for all involved. This relatively simple guideline reduced uncertainty for thirty-five expensive people.

And now, in the next section, we turn our attention to practices that I consider problematic. These practices range from isolated occurrences to commonplace misfortunes, but they all hinder us in our pursuit of keeping our work visible and holding the thieves at bay.

KEY TAKEAWAYS