CONCLUSION: CALIBRATION

Never let formal education get in the way of your learning.

—Mark Twain

Mountain View, California, September 2011

Following the first ever Kanban for DevOps class in Mountain View, California, a man sporting a kilt and long locks asked, “How do you integrate kanban with ticket systems without slowing down high-throughput Ops teams?” The man, whose name was Ben, wrote the question on a large, orange sticky note while standing at the back of the DevOps meetup room.

Now, looking at the orange note, which I saved, I remember that I didn’t know how to answer the question at the time. It’s as valid a question today as it wasin 2011. My response today begins with one comment and two questions: My comment is that any change, even a good change, impacts performance. Adding new people to the team requires some level of on-boarding and getting people up to speed. In the short term, the team will be impacted. But is it worth it? There has to be some win in order to disrupt the team. Next, my two questions are:

I would have to make a lot of assumptions to spit out an answer worth much. But for the sake of it, let’s assume that while the team has high throughput, they are overloaded and rely on heroics to meet their demand. The problem you want to make visible in this scenario would be the overwhelming demand your team is having to work through (Thief Too Much WIP) and the reason why it’s like that. Making this visible allows you to see the problem and have a think about what to do next. The answer could be to reduce WIP and reprioritize. It could also be to bring in more people to manage WIP (and to keep your current people from seeing greener pastures).

Limiting WIP can keep throughput high while reducing the level of demand as well as the problems that create and then feed into that demand, such as constant interruptions from unplanned work and burned-out team members.

This is what we’ve been talking about throughout this book: limiting the time thieves’ ability to mess with your life by exposing them, and then continuously improving on ineffective practices across teams, departments, and organizations to reap maximum benefits. Remember, exposing the time thieves is important because it’s ridiculously hard to manage invisible work. When there is too much WIP, there is no time to simply think.

When we look at time theft we can narrow it down to calibration because that’s what making work visible does. When you can see the thieves for what they are, it allows you to realign and calibrate the systemic issues that hinder your organization.

Alignment (Coherence) of Technical and Business Teams

Aligning technical and business teams is a matter of gaining clarity and consensus around why teams are doing what they’re doing. Your teams may (and in fact, should) argue about the who, what, and when, but the context around why should be well understood. Alignment problems are often related to conflicting priorities resulting from too much demand. If all requests got done, there would be no problem. Priorities conflict because there is too much WIP.

Gaining crystal clear understanding on why a company is in business in the first place can fundamentally transform the culture of an organization because leaders can go back to this to make priority decisions.

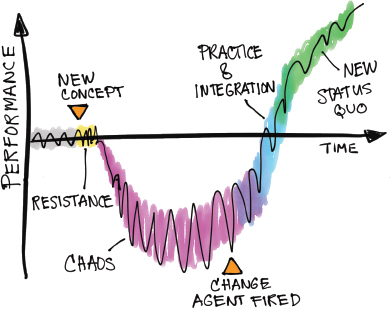

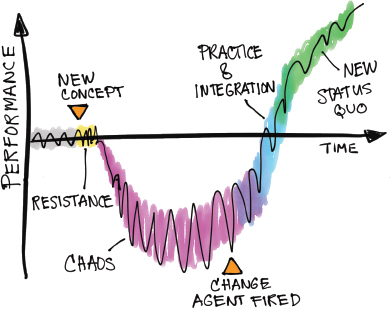

Change is hard for humans and is often met with resistance, especially during dramatic transformations. Lean coaches refer to this as the J-curve (Figure 53). Big changes cause dips in performance due to a variety of reasons: learning new material, hiring more people, installing and using new tools, yada, yada, yada. That’s why small, gradual changes are easier to implement. Small change meets with less defiance. Take eBay for example.

Figure 53. The J Curve

One day, eBay designers decided that a bright yellow background wasn’t cool anymore, so they replaced it with a white one. Customers didn’t like it one bit. So many people complained that eBay rolled the change back to yellow. Then, over a period of several months, they modified the background color one shade of yellow at a time, until all the yellow was gone and had been replaced with white.1 Hardly a single user noticed. This is the power of gradual change—it gets met with less resistance as people are only asked to adapt to one small piece at a time rather than to everything all at once. Satisfy people with gradual change instead of dramatic change.

Other challenges with rolling out a new way of working:

How you can veer off course:

As a Lean coach, I often get asked what the difference is between kanban and Scrum (an Agile framework used to complete projects). They are both Agile methods that use constraints to enable productive outcomes.

Scrum and kanban can work well together. They are more alike than they are different. Differences include release cadence, roles, and the type of constraints themselves. Scrum uses a time-box (usually two weeks) to limit demand, while kanban uses the WIP limit to constrain demand. Some teams use a hybrid of both and call it ScrumBan (originally designed as a way to transition from Scrum to kanban).

I am inspired by Klaus Leopold and Siegfried Kaltenecker who wrote a kanban elevator pitch in their book Kanban Change Leadership: Creating a Culture of Continuous Improvement.

Kanban is a method for the continuous improvement of your own area of work. You don’t begin with a big change management project, but rather focus on a series of small change steps. You identify the most important business partners and together investigate the strengths and weaknesses in your current work processes. Based on visualization of these processes, you use a simple means to make things more efficient, improve lead times and create added value for your customers.2

To investigate strengths and weaknesses with business partners, using visualization reduces resistance to change in the organization. Making work visible helps with investigation, which in turn helps people become comfortable with change.

Old school language tends to block progress. Combatting time thieves takes agility, daring, and new words to describe new ways of doing things. Think people (not resources), good practices (not best practices), and uncertainty (not exactness).

Changing how we work requires a mental shift in the way we think about things.

When Somerset County, England, changed their traffic system from lights to no lights, the townsfolk thought it wouldn’t work. “Drivers are not going to dovetail in,” they said. Surprisingly (to most citizens), after the traffic lights were removed, the queues instantly disappeared. It was less congested and easier for pedestrians to cross the street. A drive through town that used to take twenty minutes now took just five minutes. The difference was extraordinary.

It took some time for people to adjust. Most people were used to just looking at the lights. Some drivers still assumed the right of way in the time-honored fashion dictated by traffic controls. Reform required a change in culture, and people had to unlearn their bad habits. It was a new way of thinking that required a mind shift, and it took a while for people to catch on, but it resulted in a system that was ultimately safer and faster.

The same is true when moving to a Lean kanban flow approach. It’s new and different. People think it won’t work, and there is resistance across teams and departments. Culture change is often required to unlearn bad habits. The results are rarely as instantaneous as the traffic light example, but often people see some improvement early on in the form of fewer interruptions, more transparency, and a faster flow of work.

Theory and expertise in the science of quantitative measures is a valuable part of exposing time thievery and improving workflow. It interests me, and so I’ve dabbled in it. It’s the math—I like solving for x. My first ambition was to be a detective like Honey West. I’ve experienced firsthand the power to influence decisions using metrics. I’ve gotten budget and headcount approvals and agreement to pursue one direction over another because of metrics. I’ve applied them in the interest of improving the world of work.

But theory and metrics is not why I do this work. Articulating abstract or unintuitive ideas viva voce is not my strong suit. My brain competes with my own narrative. The reason I know a lot about making work visible is because in many ways (maybe in most ways), it’s easier for me to communicate visually than vocally. The act of making work and ideas visible so that people can easily see the problem or situation is exciting. Creating useful, relevant, visually available and beautiful information to help people understand what’s really going on is a true delight. But it’s not why I do this work.

I do this work because I get to connect with people at an intrinsic level. I can sense what people are dealing with from watching them at work and during workshops. Much of it comes from instinct while observing people. Ideas just come to me for how to visually shine a light on their pain. I see what’s happening at the emotional level and transform it into a physical visual to help people communicate. For me, interpreting other people’s energy to understand their situation is an automatic process. I’m a visual empathic listener, and this is what I do best. Put me in the crime scene and let me deduce away.

I would not be able to do this work without the ability to make work visible, optimize for flow, and enable important discussions. I’ve provided you with some of the essential tools and knowledge necessary to do the things that will help you become the voice of reason in your organization. It’s now up to you to take these tools and run with them.

Stop banging your head against a system that doesn’t work. The practices in this book can put you in a position to continuously experience improvements. Small improvements over time make a difference. So get out there and encourage others to join you in your journey to do the right thing. I hope I have inspired you to get started. Just start doing the exercises, visualizing the problems, and provoking the necessary conversations, and see where these actions lead you.

I doubt that I’ve covered everything you need to know to successfully expose your time thieves and optimize your workflow, but I’ve tried my best, which is all any of us can do. There are many aspects of visualizing and improving workflow that I am still learning.

When I first thought about writing this book, my brain seemed to be overflowing with ideas and examples for how everyday workers trapped in corporate bureaucracy or business stalemate could improve their world and could become the voice of reason in their organization. And that’s who I wanted to reach/teach—the everyday person just trying to do a good job and enable their team to reach a better place. A happier place. So, carry on. If I can do it, so can you.

Good luck!