Immediately after a race or workout ends, it’s time to start focusing on recovery. This should be your highest priority. The higher your athletic goals, the more important quick recovery becomes. If you aspire to achieve at your peak levels, then both the quantity and quality of training are crucial for success. The sooner you can do another key workout, the faster you will get into race shape and the better your results will be.

If everything is done right nutritionally, both before and during the exercise session, then you’re well on your way to accomplishing this result. Following exercise, your objective must be to return your body to its preexercise levels of hydration, glycogen storage, and muscle protein status as quickly as possible. Diet is the critical component in this process.

There are three stages in this process: 30 minutes postexercise (Stage III); short-term postexercise (Stage IV), lasting as long as the exercise session; and long-term postexercise (Stage V), lasting until the next Stage I. Generally these stages will occur in sequential order from I through V. But on days when multiple workouts are done with only a few hours between sessions, Stages III and IV may be completed followed by a return to Stage 1, repeating the entire process. Stage V would then be very late in the day. This is quite common for serious athletes who train and race at a high level. Stages III and IV may also be modified based on the total stress of the workout. Let’s examine the details of each stage of postexercise recovery.

Following a highly stressful workout or race, this is the most critical phase. During the first 30 minutes after exercise stops, your body is better prepared to receive and store carbohydrate than at any other time during the day. If the preceding session was challenging, your body’s glycogen stores have been significantly diminished and there may be damage to muscles as well. Get nutrition right now, and you are well on your way to the next key workout. Blow it, and you’re certain to delay recovery.

Timing is a critical component for this stage. At no other time in the day is your body as receptive as it is now to macronutrient intake. Research shows that the restocking of the muscles’ carbohydrate stores is two to three times as rapid immediately after exercise as it is a few hours later. In the same way, other research reveals that the repair of muscles damaged during exercise is more effective if protein is consumed immediately after exercise. Don’t delay. Begin refueling as soon as possible after your cooldown.

There are five goals for this brief but critical window of opportunity.

Goal #1: Replace expended carbohydrate stores. During highly intense exercise, especially if it lasted longer than about 1 hour, you used up much of your carbohydrate-based energy sources. Even though you may have taken in fuel during the session, you were unable to replace all that was expended. Muscle glycogen stores are now at a low level. These can best be restored by taking in carbohydrates that are high on the glycemic load scale for quick replenishment, along with sources that are lower on the scale to provide for a steady release of carbohydrates into the blood. Glucose, the sugar in starchy foods such as potatoes, rice, and grains, is a good source for quick recovery, while fructose, the sugar in fruit and fruit juices, provides a steady, slowly released level of sugar into the bloodstream. Take in at least three-fourths of a gram (3 calories) of carbohydrate per pound of body weight from such sources. This recovery “meal” is generally best taken in liquid rather than solid form, partly because solid foods often aren’t very appealing at this time. A liquid meal also is absorbed more quickly and contributes to the rehydration process. Good sources are commercially produced recovery drinks. Or you can make your own “homebrew” recovery drink, which is much cheaper and exactly designed to suit your tastes. (See Table 4.5.)

One of the highest glycemic load carbohydrates is glucose. By adding glucose to the homebrew, you replace the body’s expended carbohydrate stores more quickly than by eating fruit and drinking fruit juice alone, because these foods are rich in fructose, which the body takes somewhat longer to digest. Pure glucose, sometimes referred to as “dextrose,” is difficult to find, although it is typically in commercial sports and recovery drinks. You can purchase glucose from various sources on the Internet, such as amazon.com, bulkfoods.com, carbopro.com, honeyvillegrain.com, iherb.com, and nuts.com. As of this writing it cost about $3 per pound.

Goal #2: Rehydrate. Chances are good that you are experiencing some level of dehydration following a long or hard workout or race. Losing a quart of fluids an hour—about 2 pounds—is fairly common, especially on hot days. At the greatest sweat rates, an athlete may lose around a half gallon (1,800 milliliters) of sweat per hour. That’s about 4 pounds. Among the highest sweat rates ever reported in the research literature was about 1 gallon per hour in one of America’s best all-time marathoners, 147-pound Alberto Salazar. That would be about 8 pounds—roughly 5 percent of his body weight. Replacing such high rates of fluid loss during exercise is difficult, if not impossible, potentially leaving the athlete in a dehydrated state as the postexercise stage of recovery begins.

To replenish fluid levels, begin taking in 16 ounces (500 milliliters) of liquid for every pound lost during exercise. You probably won’t accomplish this in 30 minutes, especially after a long session on a hot day, so plan on continuing throughout the next few hours into Stage IV. You may need to take in 150 percent of what your weight indicates you lost just to keep up with your body’s ongoing need for fluids in the hours following the workout or race. Thirst also plays a role here just as it did during exercise. When it is quenched, whether you have replaced all lost body weight or not, reduce or stop your intake of fluids. Forcing down fluids when you are not thirsty is never a good idea.

Goal #3: Provide amino acids for resynthesis of protein that may have been damaged during exercise. In an intense 1-hour workout, it’s possible to use 30 grams (1 ounce) of muscle protein for fuel. With even longer exercise sessions, the protein cost of fueling the body is likely to rise. As carbohydrate is depleted in the working muscles, the body begins to break down protein structures within the muscle cells to create more glycogen. In addition, cells may have been damaged during exercise, and consuming protein immediately after will hasten their repair while diminishing or even preventing the delayed onset of muscle soreness.

Protein, particularly sources that are rich in the branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine), should be taken in at a carb-to-protein ratio of about 4:1 or 5:1 over the 30-minute recovery period. The research is clear on the need for protein after stressful sessions; the exact amount is not clear, however. We’ve found that 4 or 5 parts carbohydrate to 1 part protein seems to be palatable and effective. If you are using a protein powder to mix a recovery drink, the best sources of protein are egg or whey products, which contain all of the essential amino acids and a healthy dose of branched-chain amino acids, as can be seen in Table 4.1.

Table 4.2 provides a breakdown by body weight of the caloric components of a recovery drink with a 4:1 or 5:1 ratio of carbohydrate to protein. You may feel the need to take in more or fewer calories depending on how intense or long the workout was, your nutritional status prior to the session, what and how much you took in during exercise, and how good eating sounds to you at this time. Even if you don’t feel up to taking in this much immediately after your workout, at least begin to sip the recovery drink, and spread its intake over a longer period. The research on recovery meals isn’t conclusive as to how long the window is open. But 30 minutes is known to be an effective duration. The workout or race conditions may also influence how much you take in. For example, as it does with fluids, heat increases the need for both carbohydrate and protein.

TABLE 4.1

| SOURCE (100-Calorie Sample) | ISOLEUCINE (mg) | LEUCINE (mg) | VALINE (mg) | TOTAL BCAA (mg) |

| Egg white, powder | 1,200 | 1,791 | 1,352 | 4,343 |

| Egg white, raw | 1,188 | 1,774 | 1,340 | 4,302 |

| Whey protein | 922 | 1,719 | 896 | 3,537 |

| Meats | 928 | 1,474 | 967 | 3,369 |

| Soy protein | 886 | 1,481 | 923 | 3,290 |

| Seafood | 744 | 1,285 | 803 | 2,832 |

| Hard-boiled egg | 389 | 442 | 494 | 1,325 |

| Milk | 323 | 524 | 358 | 1,205 |

| Beans | 319 | 524 | 349 | 1,192 |

| Vegetables | 238 | 287 | 245 | 770 |

| Grains | 130 | 303 | 172 | 605 |

| Nuts and seeds | 111 | 198 | 149 | 458 |

| Starchy root vegetables | 45 | 66 | 58 | 169 |

| Fruits | 20 | 31 | 29 | 80 |

TABLE 4.2

| WEIGHT (lbs) | CARBOHYDRATE CALORIES (Minimum) | PROTEIN CALORIES | TOTAL CALORIES |

| 100 | 300 | 60-75 | 360-375 |

| 110 | 330 | 66-83 | 396-413 |

| 120 | 360 | 72-90 | 432-450 |

| 130 | 390 | 78-98 | 468-488 |

| 140 | 420 | 84-105 | 504-525 |

| 150 | 450 | 90-113 | 540-563 |

| 160 | 480 | 96-120 | 576-600 |

| 170 | 510 | 102-128 | 612-638 |

| 180 | 540 | 108-135 | 648-675 |

| 190 | 570 | 114-143 | 684-713 |

| 200 | 600 | 120-150 | 720-750 |

| 210 | 630 | 126-158 | 756-788 |

Goal #4: Begin replacing electrolytes. Electrolytes are the salts sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, which are found either within the body’s cells or in extracellular fluids, including blood. Dissolved in the body fluids as ions, they conduct an electric current and are critical for muscle contraction and relaxation and for maintaining fluid levels. During exercise, the body loses a small portion of these salts, primarily through sweat. So an imbalance between electrolytes and fluids occurs while sweating, with their concentrations increasing. Following exercise, as you begin to drink, you will gradually return body fluids levels to a more normal level. This will result in a low concentration of electrolytes if they aren’t taken in now.

Most of the electrolytes are found in abundance in natural food, which makes their replacement fairly easy. Drinking juice or eating fruit will easily replace nearly all of the electrolytes expended during exercise—with the exception of sodium, which is not naturally abundant in fruits and juices. Two or three pinches of table salt may be added to a postexercise recovery drink for sodium replenishment. Table 4.3 lists good juice and fruit sources to use in a Stage III postworkout drink for the replenishment of sodium, magnesium, calcium, and potassium. Chloride is not included, as there is limited research on its availability in these foods.

TABLE 4.3

| SODIUM (mg) | MAGNESIUM (mg) | CALCIUM (mg) | POTASSIUM (mg) | |

| Juice (12 oz) | ||||

| Apple, frozen | 26 | 18 | 21 | 450 |

| Grape, frozen | 7 | 16 | 12 | 80 |

| Grapefruit, frozen | 3 | 45 | 33 | 505 |

| Orange, fresh | 3 | 41 | 41 | 744 |

| Pineapple, frozen | 4 | 35 | 42 | 510 |

| Fruit | ||||

| Apple, 1 medium, raw | 1 | 6 | 10 | 159 |

| Banana, 1 medium, raw | 1 | 33 | 7 | 451 |

| Blackberries, 1 cup, frozen | 2 | 33 | 44 | 211 |

| Blueberries, 1 cup, raw | 9 | 7 | 9 | 129 |

| Cantaloupe, 1½ cups, raw | 21 | 25 | 25 | 741 |

| Grapes, 1½ cups, raw | 3 | 8 | 20 | 264 |

| Orange, 1 large, raw | 2 | 22 | 84 | 375 |

| Papaya, 1 medium, raw | 8 | 31 | 72 | 780 |

| Peaches, 3 medium, raw | 0 | 18 | 15 | 513 |

| Pineapple, 1½ cups, raw | 2 | 32 | 17 | 262 |

| Raspberries, 1½ cups, raw | 0 | 33 | 40 | 280 |

| Strawberries, 2 cups, raw | 4 | 32 | 42 | 494 |

| Watermelon, 2 cups, raw | 6 | 34 | 26 | 372 |

Goal #5: Reduce the acidity of body fluids. During exercise, body fluids trend increasingly toward acidity. There is also evidence indicating that as we age, our blood and other body fluids also have a tendency toward acidity. The cumulative effect is a slight lowering of pH (increased acidity), which the body offsets by drawing on its alkaline sources. Regardless of your age, if this acidic trend following exercise is allowed to persist for some period of time, the risk of nitrogen and calcium loss is greatly increased. The body reduces the acidity by releasing minerals into the blood as well as other body fluids that have a net alkaline-enhancing effect, thus counteracting the acid. Calcium from the bones and nitrogen from the muscles meet this need. The trend toward greater acidosis is stopped. This prevents a health catastrophe, but at a great cost.

The problem is that in neutralizing the acid this way, we give up valuable structural resources. You’re essentially peeing off bone and muscle as the acidity of your blood stays high. While cannibalizing tissue is necessary from a strictly biological perspective, this is an expensive solution from an athletic and a long-term health perspective. While body fluids may be chemically balanced by the process, future performance and health may well be jeopardized as muscle and bone are compromised.

Research has shown that fruits and vegetables have a net alkaline-enhancing effect. Table 4.4 demonstrates the acid- and alkaline-enhancing effects of various foods. The foods with a plus sign (+) indicate increased acidity; the greater the plus value, the higher the acid effect. Those foods with a minus sign (-) decrease the acid of the body fluids in direct proportion to their magnitude. So, by preparing a recovery drink with fruits and juices that have a net alkaline-enhancing effect (they reduce acidity), you are doing more than merely replacing carbohydrate stores; you’re also potentially sparing bone and muscle. Interestingly, a recent study by Cao and associates at the US Department of Agriculture found that although animal protein increased the urinary excretion of calcium, it did not have any negative consequences for bone health.

| ACID FOODS (+) | |

| Grains | |

| Brown rice | +12.5 |

| Rolled oats | +10.7 |

| Whole wheat bread | +8.2 |

| Spaghetti | +7.3 |

| Corn flakes | +6.0 |

| White rice | +4.6 |

| Rye bread | +4.1 |

| White bread | +3.7 |

| Dairy | |

| Parmesan cheese | +34.2 |

| Processed cheese | +28.7 |

| Hard cheese | +19.2 |

| Gouda cheese | +18.6 |

| Cottage cheese | +8.7 |

| Whole milk | +0.7 |

| Legumes | |

| Peanuts | +8.3 |

| Lentils | +3.5 |

| Peas | +1.2 |

| Meats, Eggs, Fish | |

| Trout | +10.8 |

| Turkey | +9.9 |

| Chicken | +8.7 |

| Eggs | +8.1 |

| Pork | +7.9 |

| Beef | +7.8 |

| Cod | +7.1 |

| Herring | +7.0 |

| ALKALINE FOODS (-) | |

| Fruits | |

| Raisins | -21.0 |

| Black currants | -6.5 |

| Bananas | -5.5 |

| Apricots | -4.8 |

| Kiwifruit | -4.1 |

| Cherries | -3.6 |

| Pears | -2.9 |

| Pineapple | -2.7 |

| Peaches | -2.4 |

| Apples | -2.2 |

| Watermelon | -1.9 |

| Vegetables | |

| Spinach | -14.0 |

| Celery | -5.2 |

| Carrots | -4.9 |

| Zucchini | -4.6 |

| Cauliflower | -4.0 |

| Potatoes | -4.0 |

| Radishes | -3.7 |

| Eggplant | -3.4 |

| Tomatoes | -3.1 |

| Lettuce | -2.5 |

| Chicory | -2.0 |

| Leeks | -1.8 |

| Onions | -1.5 |

| Mushrooms | -1.4 |

| Green peppers | -1.4 |

| Broccoli | -1.2 |

| Cucumber | -0.8 |

Reprinted from the Journal of the American Dietetic Association, V95(7), Thomas Remer and Friedrich Manz, “Potential renal acid load of foods and its influence on urine pH,” pp. 791–97, 1995, with permission from the American Dietetic Association.

Based on all of the above, then, here’s what you want in a homemade recovery drink: fruits and juices (to provide fluids and slow-releasing carbohydrate with electrolytes while reducing blood acidity), glucose (a quickly absorbed energy source), protein (to replace what was used in exercise and hasten muscle recovery from breakdown occurring during exercise), and sodium (because fruits and juices are low in this electrolyte). Using ingredients that are mostly found in your own kitchen, you can make a smoothie that fulfills all those requirements.

Start by filling a blender with about 12 to 24 ounces of fruit juice, based on your body weight (see Table 4.5). Apple, grape, grapefruit, orange, and pineapple are good choices due to their relatively high glycemic loads and electrolyte contents. Next, add a fruit from the list in Table 4.3 and glucose, also sometimes called dextrose (see Table 4.5). Then, with the blender still running, add protein powder from either egg or whey sources (see Table 4.1). Sprinkle in two or three pinches of table salt. If you didn’t use frozen berries, add a handful of ice. There you have it—a fairly inexpensive drink that has all of the ingredients needed for immediate recovery.

TABLE 4.5

| BODY WEIGHT IN POUNDS (kg) | FRUIT JUICE (oz) | GLUCOSE (tbsp) | PROTEIN POWDER (tbsp) | TOTAL CALORIES (approx.) |

| 100 (45.5) | 12 | 2 | 1½-2 | 390-415 |

| 110 (50) | 12 | 2 | 1½-2 | 390-415 |

| 120 (54.5) | 12 | 3 | 2 | 445 |

| 130 (59.1) | 12 | 4 | 2-2½ | 470-495 |

| 140 (63.6) | 16 | 4 | 2½-3 | 550-575 |

| 150 (68.2) | 16 | 4 | 2½-3 | 550-575 |

| 160 (72.7) | 16 | 5 | 2½-3 | 580-605 |

| 170 (77.3) | 20 | 5 | 3-3½ | 660-685 |

| 180 (81.8) | 20 | 5 | 3-3½ | 660-685 |

| 190 (86.4) | 24 | 5 | 3-3½ | 720-740 |

| 200 (90.9) | 24 | 5 | 3-3½ | 720-740 |

| 210 (95.5) | 24 | 6 | 3-4 | 750-790 |

Each smoothie also includes one fruit and two or three pinches of table salt.

You don’t need to use this type of recovery drink after every workout, just those that include a significant amount of intensity or last at least 60 to 90 minutes. In fact, avoid using this drink when you don’t need it, as the high glycemic load is likely to add unwanted pounds of body fat. After short and low-intensity workouts, you can make a smaller version of the homebrew without the glucose.

For very intense, short workouts or those longer than about 60 to 90 minutes, recovery needs to continue beyond the initial 30-minute window. Although there is no research supporting this, we have had success in coaching athletes who eat a Paleo diet in Stage V in continuing to focus on recovery for the same amount of time that the workout or race took. Stage III is unlikely to fully meet all of your recovery needs following a workout that lasted longer than about 90 minutes. Recovery needs to continue into Stage IV following such lengthy sessions. And the longer the workout was, the more critical Stage IV becomes. When athletes tell me they don’t recover well as Paleo dieters, I usually discover through questioning that they go straight to Stage V without inserting a Stage IV. Stage IV is critical to your recovery. Don’t omit it.

So how does Stage IV work? Let’s say you exercised for 2 hours and it was a challenging workout. The initial 30-minute recovery period (Stage III) should be followed by an additional 90 minutes in Stage IV. In the same way, a 4-hour workout or race should be followed by the standard 30 minutes in Stage III and then by 3½ hours in Stage IV. This critical stage continues the focus on “macrolevel” recovery, meaning the emphasis is still primarily on the intake of carbohydrate and protein.

As your body returns to a resting state following exercise, sensations of hunger will emerge. After not taking in any substantial food sources for perhaps several hours, the body begins to cry out for complete nutrition. How long it takes for hunger to appear depends on how long and intense the preceding exercise was, how well stocked your carbohydrate stores were before starting the session, how much carbohydrate you took in during the session, and even how efficient your body is in using fat for fuel while sparing glycogen. The foods you eat now should emphasize moderate to high glycemic load carbohydrates.

The focus of this period is similar to that of the 30-minute window preceding it. The difference is that now there is a shift toward taking in more solid foods, although continued fluid consumption is also important. Here are guidelines for eating during this extended recovery period.

Carbohydrate remains very important at this stage of recovery, but the difference is inclusion of more solid foods, especially starchy vegetables that are high on the glycemic load scale while having a net alkaline-enhancing effect on body fluids. Good choices include potatoes, yams, and sweet potatoes, as well as dried fruits, especially raisins. These are excellent to snack on or even make a meal of during Stage IV recovery because they have the greatest alkaline-enhancing effect of any food studied while also having a high glycemic load. That means a great amount of carbohydrate is delivered to the muscles quickly, which is more valuable at this time than having a high glycemic index. Table 4.6 lists the glycemic loads of various alkaline-enhancing fruits, juices, and vegetables. Notice that while some foods, such as watermelon, have a high glycemic index, their glycemic loads are low; the lower the load, the more of the food you will need to eat. Glycemic load is a measure of not only how quickly a food’s sugar gets into your blood but also how much sugar is delivered. The foods listed first are preferred, but all are good choices. You may also select grains such as corn, bread, a bagel, rice, and cereal to continue the rapid replacement of carbohydrate stores. Grains are not optimal, for while most have a high glycemic load, they have a net acid-enhancing effect, so be certain to include plenty of vegetables, fruits, and fruit juices to counteract the negative consequence.

During this extended recovery stage, continue taking in carbohydrate at the rate of at least 0.75 gram (3 calories) per pound of body weight per hour. Otherwise, your appetite may serve as a guide as to how much to eat. After especially long or intense exercise, you may find liquids more appealing than solids. If so, continue using a recovery drink, just as in the first 30 minutes postexercise.

At this time you must also maintain your lean protein intake, using the same 4:1 or 5:1 ratio with carbohydrate. The purpose, as before, is to continue providing amino acids for the resynthesis of muscle protein and maintenance of other physiological structures that rely on amino acids, such as the nervous system. Animal products are the best sources of this protein because they’re rich in essential amino acids, including the branched-chain amino acids that we now know to be critical to the recovery process. Fish, shellfish, egg whites, and turkey breast are excellent choices. It is best to avoid farm-bred fish and feedlot-raised animals, and not just at this time but throughout the day. The physical composition of their meat, especially the oils, is dramatically different from that of wild game and free-ranging animals. It’s common for Paleo athletes to keep a stock of boiled eggs, deli-sliced turkey breast, tuna salad, and other such protein sources easily available in their refrigerators just for this purpose.

TABLE 4.6

| FOOD | GLYCEMIC LOAD | GLYCEMIC INDEX |

| Raisins | 48.8 | 64 |

| Potato, plain | 18.4 | 85 |

| Sweet potato | 13.1 | 54 |

| Banana | 2.1 | 53 |

| Yam | 11.5 | 51 |

| Pineapple | 8.2 | 66 |

| Grapes | 7.7 | 43 |

| Kiwifruit | 7.4 | 52 |

| Carrots | 7.2 | 71 |

| Apple | 6.0 | 39 |

| Pineapple juice | 5.9 | 46 |

| Pear | 5.4 | 36 |

| Cantaloupe | 5.4 | 65 |

| Watermelon | 5.2 | 72 |

| Orange juice | 5.1 | 50 |

| Orange | 5.1 | 43 |

| Apple juice | 4.9 | 40 |

| Peach | 3.1 | 28 |

| Strawberries | 2.8 | 40 |

If you continue eating fruits and vegetables now, you will also restock electrolytes that may be necessary for recovery, depending on how long the exercise session was and how hot the weather.

It’s still important to drink adequate amounts to satisfy your thirst. This may vary greatly depending on how long the session lasted, its intensity, and the weather. Thirst will tell you when to drink and when to stop. Fruit juices are an excellent choice because they also bolster carbohydrate stores and are rich in most electrolytes. If you’ve otherwise met your carbohydrate-restocking needs by late in Stage IV, then drink water to quench thirst.

Again, we want to emphasize how critical it is to follow these Stage IV recovery guidelines, especially after very long and stressful sessions. If you rush into Stage V directly from Stage III after a long and hard workout or race, then your full recovery may well be delayed.

You’ve gotten yourself through a grueling workout and refueled as you should in Stages I through IV of recovery. You’re back at work or in class, spending time with the family, maintaining your house and landscaping—whatever it is you do when you’re not training or racing. This part of your day may look ordinary to the rest of the world, but it really isn’t. You’re still focused on nutrition for long-term recovery.

This is the time when many athletes get sloppy with their diets. The most common mistake is to continue eating a high glycemic load diet that is low in micronutrient value and marked by the high starch and sugar intake prescribed for Stages III and IV. Eating in this way compromises your development as an athlete. It’s a shame to spend hours training only to squander a portion of the potential fitness gains by eating less-than-optimal foods.

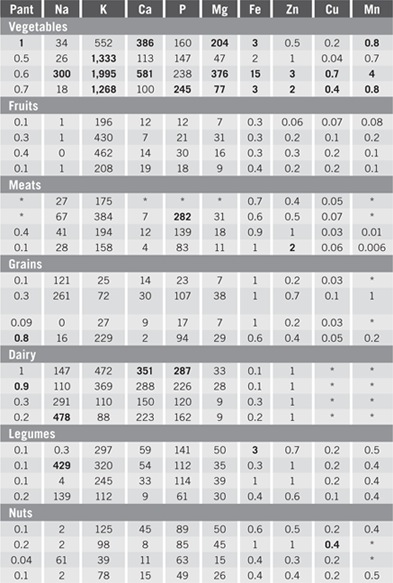

What are optimal foods? These are the categories of foods that have been eaten by our Paleolithic ancestors for millions of years; the ones to which we are fully adapted through an inheritance of genes from the many generations that preceded us here on Earth: fruits, vegetables, and lean protein from animal sources. Optimal foods also include nuts, seeds, and berries. These are also the most micronutrient-dense foods available to us—they’re rich in vitamins, minerals, and other trace elements necessary for health, growth, and recovery. Table 4.7 compares the vitamin and mineral density of several foods. Those with the highest content are in boldface. Notice that vegetables especially provide an abundant level of vitamins and minerals; most other foods pale by comparison.

In terms of athletic performance, the nutritional goals and guidelines for this stage of recovery are as follows.

Maintain glycogen stores. For some time prior to this stage of recovery, you intently focused your diet around carbohydrate, especially high glycemic load sources such as the sugars in starchy foods. While these foods are excellent for restocking the body’s glycogen stores, they are not nutrient dense (see Table 4.7). There is no longer a need to eat large quantities of such foods; in fact, they will diminish your potential for recovery. Every calorie eaten from a less-than-optimal food means a lost opportunity to take in much larger amounts of health- and fitness-enhancing vitamins and minerals from vegetables, fruits, and lean animal protein. The more serious you are about your athletic performance, the more important this is.

TABLE 4.7

The highest vitamin and mineral contents in each column are indicated by a bold listing.

* No information available

Furthermore, one of the beauties of the human body is that, regardless of which system or function we are talking about, it takes less concentrated effort to maintain than to rebuild. This means that by eating prodigious quantities of high glycemic load carbohydrates in the previous stages, you’ve rebuilt your body’s glycogen stores, and now less carbohydrate is required to maintain that level. Low glycemic load fruits and vegetables will accomplish that while also providing the micronutrients needed for this last stage of recovery.

Rebuild muscle tissues. Despite your best efforts to take in amino acids in recovery, if the workout was sufficiently difficult, you will have suffered some muscle cell damage. If you could use an electron microscope to look into the muscles used in an intensely hard training today, it would look like a war zone, albeit a very tiny one. You would see tattered cell membranes and leaking fluids. The body would be mobilizing its “triage services” to repair the damage as quickly as possible. To do this, the body needs amino acids in rather large quantities. Most needed are the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) you read about earlier. Without them, the body is forced to cannibalize other protein cells to find sufficient amounts of the right amino acids to complete the job. Also needed are the essential amino acids, those that the body cannot produce and that must come from food.

BCAA and essential amino acids are most abundant in animal products. If you’re hesitant to eat red meat from feedlot-raised animals, we don’t blame you. The common beef products you buy in supermarkets are a poor source of food. While certainly rich in BCAA, meats from feedlot-raised animals are also packed with omega-6 polyunsaturated fats and other questionable chemical additives and are best avoided.

So what should you eat to provide BCAA and the essential amino acids for your rebuilding muscles? The best possible source would be meat from game animals such as deer, elk, and buffalo. Of course, chances are that you don’t have the time to go hunting, given your workout and career choices. (For our ancestors, hunting was exercise and career all rolled into one activity.) No, it’s unlikely that you will find game meat outside your back door, and it can’t be sold in supermarkets, either. But there are other readily available choices that are almost as good.

TABLE 4.8

| TRAINING VOLUME IN HOURS/WEEK | PROTEIN/DAY/POUND OF BODY WEIGHT IN GRAMS (calories) |

| < 5 | 0.6-0.7 (2.4-2.8) |

| 5-10 | 0.7-0.8 (2.8-3.2) |

| 10-15 | 0.8-0.9 (3.2-3.6) |

| 16-20 | 0.9-1.0 (3.6-4.0) |

| > 20 | 1.0 (4.0) |

Ocean- or stream-caught fish and shellfish are among the best protein sources; they are, after all, wild game. It’s best, however, to avoid farm-raised fish, which is essentially the same as feedlot-raised cattle. Another good choice is turkey breast. It comes as close to providing the lean protein and fat makeup of game animals as any domestic meat available. It’s still a good idea to seek out meat from turkeys that were allowed to range freely in search of food. The same goes for any meat you may choose. Free-ranging animals have not only exercised but have also more likely eaten foods that are optimal for their health. This means that omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fats are in better balance. You’ll find that such meats are more expensive than the more common meat of penned-up animals. It’s just like so much in life: Quality costs more. You get what you pay for.

In Stage V, continue to take in 0.6 gram to 1 gram (2.4 to 4 calories) of protein per pound of body weight relative to your training load. The longer or more intense your exercise was, the more protein you should take in, as shown in Table 4.8.

Maintain a healthy pH. In our discussion of Stage III, we told you about the acid- and base-enhancing properties of foods, illustrated by Table 4.4. The need to maintain a healthy pH continues in this stage in order to reduce the risk of losing nitrogen and calcium. This is especially critical for older athletes whose bodies tend toward acidity more so than young athletes’. As explained earlier, nitrogen is an essential component of muscle, and calcium is crucial for bone health. Fortunately, the very foods that are the most nutrient-dense are also the ones—the only ones—that reduce blood acidity: fruits and vegetables. Any fruit will do now, so eat whichever appeal to you. As for vegetables, it’s best to choose those of vibrant colors—red, yellow, green, and orange—while avoiding white ones. Be aware that beans, although often categorized as vegetables, are net acid-enhancing and best avoided. This includes peanuts, which are legumes.

Prevent or reduce inflammation. All athletes are susceptible to inflammation of muscles and tendons—it comes with the territory. You may have a tendon that is a persistent problem for you following high-effort workouts and sometimes flares up, causing pain or discomfort. Muscle tissue damaged during an intense workout may also result in inflammation. If allowed to go unchecked, nagging inflammation can become a full-blown injury, causing you to miss training and lose fitness. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fat supplements have been shown to reduce inflammation by lowering the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids, which should be approximately two parts omega-6 to one part omega-3 or less. Due to the high intake of omega-6 from snacks and other packaged foods that are abundant in our society, the average American diet has a 10:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3. In fact, avoiding omega-6 is quite a challenge in Western society. By consuming foods that are rich in omega-3—cold-water fish, leafy vegetables, macadamia nuts and walnuts, eggs enriched with omega-3, and liver—you can lower this ratio and reduce your inflammation risk. We recommend that to improve the odds of accomplishing this, you take an omega-3 supplement, such as fish oil or flaxseed oil.

Optimize body weight. For most endurance sports, maintaining a low body mass translates into better performances (see Chapter 6 for more details on this). Yet, even with a lot of daily exercise to burn calories, avoiding weight gain can be a struggle for many endurance athletes. We think you will find that by eating a Stage V diet made up primarily of fruits, vegetables, and animal protein, weight control will not be a problem. It’s when you eat less-than-optimal foods that you tend to add body fat.

On a conventional Stone Age nutrition plan, such as the one described in The Paleo Diet, a person would be eating much more protein and less carbohydrate than the diet we suggest here for athletes. The shift toward more carbohydrate is due to the need to quickly recover from strenuous exercise, a need that the average, sedentary person does not have—and that our Stone Age ancestors did not have. For the athlete who trains more than once per day or has exceptionally long workouts, as is common with many serious athletes, the absolute carbohydrate intake is even higher because the need to recover increases as the number of training hours rises.

For example, an athlete training once a day for 90 minutes may burn 600 calories from carbohydrate during exercise and needs to take in at least that much during Stages I, II, III, and IV of recovery. This athlete may be eating around 3,000 total calories daily. If he gets 50 percent of his daily calories from carbohydrate, he would take in an additional 900 calories in carbs that day in Stage V, above and beyond the carbohydrate consumed in the earlier stages of the day. Of course, this carbohydrate should primarily come from fruits and especially vegetables, so calories aren’t wasted by eating foods lacking in micronutrients.

The high-volume athlete may do two of these 90-minute exercise sessions a day, thus doubling the total requirement for carbohydrate to 1,200 calories during the first four stages that day. This shift toward greater volume of training also should be accompanied by an increase in total calories consumed daily. Say 3,600 calories are taken in on such a day; if the athlete is also eating a half-carbohydrate diet, he will need another 600 calories from carbohydrate sources this day in Stage V. This illustrates how the absolute carbohydrate intake varies with the training load of the athlete, despite the percentage of intake being the same.

Getting too little carbohydrate in the diet is seldom a problem for athletes; it’s abundant in grocery stores, inexpensive, and enjoyable to eat. No, the real stumbling block is protein intake. When we do dietary assessments of athletes, we typically find that they aren’t eating enough protein. Why? Because protein is not abundant in stores, it’s relatively expensive, and it’s not as enjoyable to eat as a sweet or starchy food. Protein in the form of meat has also gotten a bad rap in the last few decades. We’ve been taught that animal meat is bad for us, as it contributes to heart disease, cancer, and assorted other evils. The problem with this conclusion is that it doesn’t isolate the true causes of these diseases. It’s not protein that is to blame for Western society’s health woes but, largely, the omega-6 fats and other additives that often accompany it. And combining saturated fat with high glycemic load foods (think mashed potatoes and gravy or bread and butter) is a double whammy. Protein from free-ranging animals and fish does not cause heart disease. And, in fact, is quite healthy.

Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Feedlot-produced animal protein should be eliminated from your diet, but not the protein from free-ranging animals. Fish, shellfish, and turkey breast are excellent sources of healthy protein and rich in essential and branched-chain amino acids. For now, the take-home message is that athletes need an abundance of amino acids daily, and these are best found in free-ranging animal sources.

Since protein is so important to your total recovery, this is a good place to begin deciding what to eat at meals in Stage V. The first concept to understand is that the amount of protein you need is related to how much you train. For the average person on the street who does little or no exercise, the level of protein intake stays much the same from day to day, as physical activity is usually quite limited. It’s different for the athlete who often pushes his or her body to near its limits and, in the process, potentially damages a lot of muscle tissue while perhaps using some protein as fuel. The greater your training volume or intensity, the greater the likelihood such cellular harm will occur. A considerable amount of amino acids from animal protein sources is needed in the hours of Stage V recovery to repair this tissue and prevent the body from seeking amino acids from internal sources, such as other muscles or the immune system. Without adequate protein, the risk of a compromised immune system increases and the possibility of muscle wasting rises.

Table 4.8 provides general guidelines for how much protein to eat with regard to your weekly training volume. Intensity of training is much harder to quantify, but you may also assume that when doing a lot of interval training, hill work, resistance training, or other high-effort exercise, you probably need to increase your protein intake to the next level in the table.

The next matter is deciding where you will get this lean protein. You may be aware that you can obtain all of the essential amino acids by mixing grains and legumes in a meal. Each of those food categories is lacking in one or more of the essential amino acids, but when you eat them in combination, the meal becomes more balanced (although plant-based diets will always be lacking in the essential amino acids lysine and tryptophan). What is not generally explained, however, is that the volume of plant-based foods one has to eat to get adequate daily protein (see Table 4.9) requires eating considerable amounts of grains and beans because these foods are nutritionally poor. In addition, they contribute to body acidity and the loss of nitrogen and calcium (see Table 4.4). A serious athlete attempting to get nearly a gram of protein per pound of body weight from a combination of grains and legumes would need to eat all day long—and have a gut that can process a significant amount of fiber. Even if he or she could do this, blood acidity levels would stay high, and anti-nutrients would prevent the absorption of much of the limited micronutrients these foods have.

| FOOD (100-calorie serving size) | PROTEIN CONTENT (grams) | ESSENTIAL AMINO ACID CONTENT (grams) |

| Animal | ||

| Cod (3.4 oz) | 22 | 8.7 |

| Shrimp (3.6 oz) | 21 | 8.2 |

| Lobster (3.6 oz) | 21 | 8.1 |

| Halibut (2.5 oz) | 19 | 7.5 |

| Chicken (2 oz) | 18 | 6.8 |

| Turkey breast (2 oz) | 17 | 6.9 |

| Tuna (1.9 oz) | 16 | 6.3 |

| Tenderloin steak (1.75 oz) | 14 | 5.1 |

| Eggs, whole (1¼) | 7.7 | 3.4 |

| Legumes | ||

| Tofu (½ cup) | 10 | 3.6 |

| Kidney beans (½ cup) | 7 | 2.8 |

| Navy beans (1⁄3 cup) | 6 | 1.9 |

| Red beans (½ cup) | 5 | 2.5 |

| Peanut butter (1 tbsp) | 4.6 | 1.4 |

| Grains | ||

| Brown rice (½ cup) | 2.1 | 0.7 |

| Whole-wheat bread (1½ slices) | 3 | 0.8 |

| Corn (3⁄4 cup) | 3.7 | 1.4 |

| Bagel (½ bagel) | 3.8 | 1.1 |

A 150-pound athlete training 15 hours a week would need to take in about 135 grams of protein a day (150 x 0.9), according to Table 4.8. Assuming 20 percent of that comes from assorted vegetables, fruits, fruit juices, sports bars, and sports drinks consumed throughout the day, including during the workout, another 108 grams of protein would be needed that day. To get that from animal sources, he could eat:

4 ounces of cod

6 ounces of turkey breast

4 ounces of chicken

Those foods would provide all of the additional protein and contain 44.5 grams of the all-important essential amino acids for our theoretical athlete. The total energy eaten to get these nutrients would be 454 calories. To get the same amount of protein by combining grains and beans, he would have to eat all of the following in one day:

1 cup of tofu

1 cup of kidney beans

6 slices of whole wheat bread

1 cup of navy beans

1½ cups of corn

1 cup of red beans

1 cup of brown rice

2 bagels

2 tablespoons of peanut butter

Our athlete had better like beans and have a huge appetite! The above requires eating an additional 2,300 calories that day—more than five times as much as when eating animal products—just to get 108 grams of protein. Eating grains and legumes to get daily protein is not only very inefficient, but, far worse, the vegetarian athlete will come up short on essential amino acids—even if he or she can stomach all those beans and grains.

Just as there are good and bad sources of carbohydrate and protein, there are fats and oils you should pursue in your daily diet and certain others to avoid. The desirables include omega-3 polyunsaturated and monounsaturated types. As described earlier in this chapter, lowering the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 has positive implications for reducing the likelihood of inflammation, a persistent problem for athletes. Omega-6s, while necessary for health, are more than abundant in our modern diet. This fat is common in vegetable oils such as soybean, peanut, cottonseed, safflower, sunflower, sesame, and corn. Most snack foods and many grain products, including breads and bagels, rely heavily on vegetable oils due to their low cost.

Monounsaturated fats should also be included in the athlete’s diet because of their health benefits, including lowering cholesterol and triglyceride levels, thinning the blood, preventing fatal heartbeat irregularities, and reducing the risk of breast cancer. Remember that health always comes before fitness. Good sources of monounsaturated fat are avocados, nuts, and olive oil.

Avoid the fats found in abundance in whole dairy foods and feedlot-raised animals, especially beef, and trans fat found in many of the foods in our grocery stores—not only snack foods but also many bread products, peanut butter, margarine, and packaged meals. Steer clear of trans fat, referred to as “partially hydrogenated” oil on food labels, whenever possible. Trans fat increases LDL (the “bad” cholesterol associated with heart disease) and also decreases your body’s production of HDL (the “good” cholesterol linked with a low incidence of heart disease). That’s a double whammy best avoided.