So far these narratives have looked at one aspect of a system and explored the various options for handling it. Now it’s time to sweep everything together and start to answer the tricky question of what patterns to use when designing an enterprise application.

The advice in this chapter is in many ways a repeat of the advice given in earlier chapters. I must admit that I’ve wondered whether this chapter was needed. However, I felt it was good to put all the discussion in context now that, I hope, you have at least an outline of the full scope of the patterns in this book.

As I write this, I’m very conscious of the limitations of my advice. Frodo said in Lord of the Rings, “Go not to the Elves for counsel, for they will say both no and yes.” While I’m not claiming any immortal knowledge, I certainly understand their answer that advice is often a dangerous gift. If you’re reading this to make architectural decisions for your project, you know far more about your project than I do. One of the biggest frustrations in being a pundit is that people often come up to me at a conference or send an e-mail message asking for advice on their architectural or process decisions. There’s no way you can give particular advice on the basis of a five-minute description. I write this chapter with even less knowledge of your predicament.

So, read this chapter in the spirit in which it’s presented. I don’t know all the answers, and I certainly don’t know your questions. Use this advice to prod your thinking, but don’t use it as a replacement for your thinking. In the end you have to make, and live with, the decisions yourself.

One good thing is that your decisions are not cast forever in stone. Architectural refactoring is hard, and we’re still ignorant of its full costs, but it isn’t impossible. Here the best advice I can give is that, even if you dislike the full story of extreme programming [Beck XP], you should still consider seriously three technical practices: continuous integration [Fowler CI], test driven development [Beck TDD], and refactoring [Fowler Refactoring]. These won’t be a panacea, but they’ll make it much easier for you to change your mind when you discover you need to. And you will need to, unless you’re either more fortunate, or more skillful, than anyone I’ve met to date.

The start of the process is deciding which domain logic approach to go with. The three main contenders are Transaction Script (110), Table Module (125), and Domain Model (116).

As I indicated in Chapter 2 (page 25), the strongest force that drives you through this trio is the complexity of the domain logic, something currently impossible to quantify, or even qualify, with any degree of precision. But other factors also play in the decision, in particular, the difficulty of the connection with a database.

The simplest of the three patterns is Transaction Script (110). It fits with the procedural model that most people are still comfortable with. It nicely encapsulates the logic of each system transaction in a comprehensible script. And it’s easy to build on top of a relational database. Its great failing is that it doesn’t deal well with complex business logic, being particularly susceptible to duplicate code. If you have a simple catalog application with little more than a shopping cart running off a basic pricing structure, then Transaction Script (110) will fill the bill perfectly. However, as your logic gets more complicated your difficulties multiply exponentially.

At the other end of the scale is the Domain Model (116). Hard-core object bigots like myself will have an application no other way. After all, if an application is simple enough to write with Transaction Scripts (110), why should our immense intellects bother with such an unworthy problem? Also, my experiences lead me to have no doubt that with really complex domain logic nothing can handle this hell better than a rich Domain Model (116). Once you get used to working with a Domain Model (116) even simple problems can be tackled with ease.

Yet the Domain Model (116) has its faults. High on the list is the difficulty of learning how to use a domain model. Object bigots often look down their noses at people who just don’t get objects, but the consequence is that a Domain Model (116) requires skill if it’s to be done well—done poorly it’s a disaster. The second big difficulty of a Domain Model (116) is its connection to a relational database. Of course, a real object zealot finesses this problem with the subtle flick of an object database. But for many, mostly nontechnical, reasons an object database isn’t a possible choice for enterprise applications. The result is the messy relational database connection. Let’s face it, object models and relational models don’t fit well together. The complexity of many of the O/R mapping patterns I describe is the result.

Table Module (125) represents an attractive middle ground between these poles. It can handle domain logic better than Transaction Scripts (110). Also, while it can’t touch a real Domain Model (116) on handling complex domain logic, it fits really well with a relational database—and many other things too. If you have an environment such as .NET, where many tools orbit around the all-seeing Record Set (508), then Table Module (125) works nicely by playing to the strengths of the relational database and yet representing a reasonable factoring of the domain logic.

In this argument we see that the tools you have also affect your architecture. Sometimes you’re able to choose the tools based on the architecture, and in theory that’s the way you should go. In practice, however, you often have to match your architecture to your tools. Of the three patterns Table Module (125) is the one whose star rises the most when you have tools that match it. It’s a particularly strong choice for .NET environments, since so much of the platform is geared around Record Set (508).

If you read the discussion of domain logic in Chapter 2, much of this will seem familiar. Yet I think it’s worth repeating here because I really do think this is the central decision. From here we go downward to the database layer, but now the decisions are shaped by the context of your domain layer choice.

Once you’ve chosen your domain layer, you have to figure out how to connect it to your data sources. Your decisions are based on your domain layer choice, so I’ll tackle this in separate sections, driven by that choice.

The simplest Transaction Scripts (110) contain their own database logic, but I avoid that even in the simplest cases. Separating the database delimits two parts that make sense as separate, so I make the separation even in the simplest applications. The database patterns to choose from here are Row Data Gateway (152) and Table Data Gateway (144).

The choice between the two depends much on the facilities of your implementation platform and on where you expect the application to go in the future. With a Row Data Gateway (152) each record is read into an object with a clear and explicit interface. With Table Data Gateway (144) you may have less code to write since you don’t need all the accessor code to get at the data, but you end up with a much more implicit interface that relies on accessing a record set structure that’s little more than a glorified map.

The key decision, however, lies in the rest of your platform. Having a platform that provides a lot of tools that work well with Record Set (508), particularly UI tools or transactional disconnected record sets, tilts you decisively in the direction of a Table Data Gateway (144).

You usually don’t need any of the other O/R mapping patterns in this context. The structural mapping issues are pretty much absent since the in-memory structure maps to the database structure so well. You might consider a Unit of Work (184), but usually it’s easy to keep track of what’s changed in the script. You don’t need to worry about most concurrency issues because the script often corresponds almost exactly to a system transaction. Thus, you can just wrap the whole script in a single transaction. The common exception is where one request pulls data back for editing and the next request tries to save the changes. In this case Optimistic Offline Lock (416) is almost always the best choice. Not only is it easier to implement, it also usually fits users’ expectations and avoids the problem of a hanging session leaving all sorts of things locked.

The main reason to choose Table Module (125) is the presence of a good Record Set (508) framework. In this case you’ll want a database mapping pattern that works well with Record Sets (508), and that leads you inexorably toward Table Data Gateway (144). These two patterns fit together as if it were a match made in heaven.

There’s not really anything else you need to add on the data source side with this pattern. In the best cases the Record Set (508) has some kind of concurrency control mechanism built in, which effectively turns it into a Unit of Work (184), further reducing hair loss.

Now things get interesting. In many ways the big weakness of Domain Model (116) is that the connection to the database is complicated. The degree of complication depends on the complexity of this pattern.

If your Domain Model (116) is fairly simple, say a couple of dozen classes that are pretty close to the database, then an Active Record (160) makes sense. If you want to decouple things a bit, you can use either Table Data Gateway (144) or Row Data Gateway (152) to do that. Whether you separate or not isn’t a huge deal either way.

As things get more complicated, you’ll need to consider Data Mapper (165). This is the approach that delivers on the promise of keeping your Domain Model (116) as independent as possible of all the other layers. But Data Mapper (165) is also the most complicated one to implement. Unless you either have a strong team or you can find some simplifications that make the mapping easier to do, I’d strongly suggest getting a mapping tool.

Once you choose Data Mapper (165) most of the patterns in the O/R mapping section come into play. In particular I heartily recommend Unit of Work (184), which acts as a focal point for concurrency control.

In many ways the presentation is relatively independent of the choice of the lower layers. Your first question is whether to provide a rich-client interface or an HTML browser interface. A rich client will give you a nicer UI, but then you need a certain amount of control and deployment of your clients. My preference is to pick an HTML browser if you can get away with it and a rich client if that’s not possible. Rich clients will usually take more effort to program, but that’s because they tend to be more sophisticated, not so much because of the inherent complexities of the technology.

I haven’t explored any rich-client patterns in this book, so if you choose one I don’t really have anything further to say.

If you go the HTML route, you have to decide how to structure your application. I certainly recommend the Model View Controller (330) as the underpinning for your design. That done, you’re left with two decisions, one for the controller and one for the view.

Your tooling may well make your choice for you. If you use Visual Studio, the easiest way to go is Page Controller (333) and Template View (350). If you use Java, you have a choice of Web frameworks to consider. Popular at the moment is Struts, which will lead you to a Front Controller (344) and a Template View (350).

Given a freer choice, I’d recommend Page Controller (333) if your site is more document oriented, particularly if you have a mix of static and dynamic pages. More complex navigation and UI lead you toward a Front Controller (344).

On the view front the choice between Template View (350) and Transform View (361) depends on whether your team uses server pages or XSLT in programming. Template Views (350) have the edge at the moment, although I rather like the added testability of Transform View (361). If you have the need to display a common site with multiple looks and feels, you should consider Two Step View (365).

How you communicate with the lower layers depends on what kind of layers they are and whether they’re always going to be in the same process. My preference is to have everything run in one process if you can—that way you don’t have to worry about slow inter-process calls. If you can’t do that, you should wrap your domain layer with Remote Facade (388) and use Data Transfer Object (401) to communicate to the Web server.

In most of this book I’m trying to bring out the common experience of doing projects on many different platforms. Experience with Forte, CORBA, and Smalltalk translates very effectively into developing with Java and .NET. The only reason I’ve concentrating on Java and .NET environments is that they look like the most common platforms for enterprise application development in the future. (Although I’d like to see the dynamically typed scripting languages, in particular Python and Ruby, give them a run for their money.)

In this section I want to apply the above advice to these two platforms. As soon as I do this, though, I’m in danger of dating myself. Technologies change much more rapidly than these patterns, so as you read remember that I’m writing in early 2002, when everyone is saying that economic recovery is just around the corner.

Currently the big debate in the Java world is exactly how valuable Enterprise Java Beans are. After as many final drafts as The Who had farewell concerts, the EJB 2.0 specification has finally appeared. But you don’t need EJB to build a good J2EE application, despite what EJB vendors tell you. You can do a great deal with POJOs (plain old Java objects) and JDBC.

The design alternatives for J2EE vary in terms of the patterns you’re using, and again they break out by domain logic.

If you use Transaction Script (110) on top of some form of Gateway (466), the common approach with EJB at the moment is to use session beans as a Transaction Script (110) and entity beans as a Row Data Gateway (152). This is a pretty reasonable architecture if your domain logic is sufficiently modest. However, one problem with such a beany approach is that it’s hard to get rid of the EJB server if you find you don’t need it and you don’t want to cough up the license fees. The non-EJB approach is a POJO for the Transaction Script (110) on top of either a Row Data Gateway (152) or a Table Data Gateway (144). If JDBC 2.0 row sets get more acceptance, that’s a reason to use them as Record Sets (508) and that leads to a Table Data Gateway (144).

If you’re using a Domain Model (116), the current orthodoxy is to use entity beans. If your Domain Model (116) is pretty simple and matches your database well, doing that makes reasonable sense and your entity beans will then be Active Records (160). It’s still good practice to wrap your entity beans with session beans acting as Remote Facades (388) (although you can also think of Container Managed Persistance (CMP) as a Data Mapper (165)). However, if your Domain Model (116) is more complex, you want it to be entirely independent of the EJB structure so that you can write, run, and test your domain logic without having to deal with the vagaries of the EJB container. In that model I would use POJOs for the Domain Model (116) and wrap them with session beans acting as Remote Facades (388). If you choose not to use EJB, I would run the whole app in the Web server and avoid any remote calls between presentation and domain. If you’re using POJO Domain Model (116), I would also use POJOs for the Data Mappers (165)—either using an O/R mapping tool or rolling something myself if I felt up to it.

If you use entity beans in any context, avoid giving them a remote interface. I never understood the point of giving entity beans a remote interface in the first place. Entity beans are usually used as Domain Models (116) or as Row Data Gateways (152). In either case they need a fine-grained interface to play those roles well. As I hope I’ve drilled into your psyche, however, that a remote interface must always be coarse-grained, so keep your entity beans local only. (The exception to this is the Composite Entity pattern from [Alur et al.], which is a different way of using entity beans and not one I find very useful.)

At the moment the Table Module (125) isn’t common in the Java world. It will be interesting to see if more tooling surrounds the JDBC row set—if it does this pattern could become a viable approach. In this case the POJO approach fits best, although you can also wrap the Table Module (125) with session beans acting as Remote Facades (388) and returning Record Sets (508).

Looking at .NET, Visual Studio, and the history of application development in the Microsoft world, the dominant pattern is Table Module (125). Although object bigots tend to dismiss this as meaning only that Microsofties don’t get objects, Table Module (125) does present a valuable compromise between Transaction Script (110) and Domain Model (116), with an impressive set of tools that take advantage of the ubiquitous data set acting as a Record Set (508).

As a result Table Module (125) has to be the default choice for this platform. Indeed, I see no point at all in using Transaction Scripts (110) except in the very simplest of cases, and even then they should act on and return data sets.

This doesn’t mean that you can’t use Domain Model (116). Indeed, you can build a Domain Model (116) just as easily in .NET as you can in any other OO environment. However, the tools don’t give you the extra help they do for Table Modules (125), so I would tolerate more complexity before I felt the need to shift to a Domain Model (116).

The current hype in .NET is all about Web services, but I wouldn’t use Web services inside an application, I’d use them, as in Java, as a presentation to allow applications to integrate. There’s no real reason to make the Web server and the domain logic into separate processes in a .NET application, so Remote Facade (388) is less useful here.

There’s usually a fair bit of debate over stored procedures. They’re often the fastest way to do things since they run in the same process as your database and thus reduce the laggardly remote calls. However, most stored procedure environments don’t give you good structuring mechanisms for your stored procedures, and stored procedures will lock you into a particular database vendor. (A nice way to avoid these problems is Oracle’s approach of allowing you to run Java applications inside your database process; this is equivalent to putting your whole domain logic layer inside the database. For the moment this still leaves you with some vendor lockin, but it at least reduces porting costs.)

For the reasons of modularity and portability a lot of people avoid using stored procedures for business logic. I tend to side with that view unless there’s a strong performance gain to be had, which, to be fair, there often is. In that case I take a method from the domain layer and happily move it into a stored procedure. I do this only on clear performance problem areas, treating it as an optimization step rather than as an architectural principle. ([Nilsson] presents a good argument for using stored procedures more widely.)

A common way of using stored procedures is to control access to a database, along the lines of a Table Data Gateway (144). I don’t have any strong feelings about whether or not to do this, and from what I’ve seen there’s no strong reasons either way. In any case I prefer to isolate the database access with the same patterns, whether database access is through stored procedures or more regular SQL.

As I write this, the general consensus among pundits is that Web services will make reuse a reality and drive system integrators out of business, but I’m not holding my breath. Within these patterns Web services don’t play a huge role because they’re about application integration rather than application construction. You shouldn’t try to break up a single application into Web services that talk to each other unless you really need to. Rather, build your application and expose various parts of it as Web services, treating those Web services as Remote Facades (388). Above all, don’t let all the buzz about how easy it is to build Web services make you forget about the First Law of Distributed Object Design (page 89).

Although most published examples I’ve seen use Web services synchronously, rather like an XML RPC call, I prefer them as asynchronous and message based. While I don’t have any patterns for that here (this book is big enough as it is), I expect that we’ll see some patterns for asynchronous messaging in the next few years.

I’ve built my discussion around three primary layers, but my approach to layering isn’t the only one that makes sense. Other good architectural books have layering schemes, and they all have value. It’s worth looking at these other schemes and comparing them to what I have here. You may find they make more sense for your application.

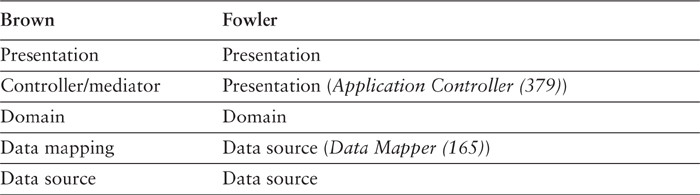

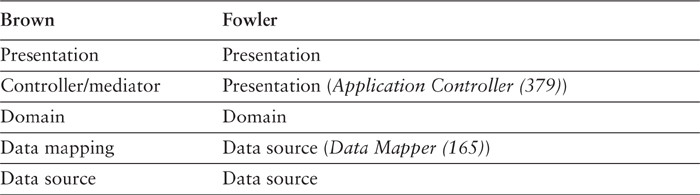

First up is what I’ll call the Brown model, which is discussed in [Brown et al.] (see Table 8.1). This model has five layers: presentation, controller/mediator, domain, data mapping, and data source. Essentially it places additional mediating layers between the basic three layers. The controller/mediator mediates between the presentation and domain layers, while the data mapping layer mediates between the domain and data source layers.

I find that the mediating layers are useful some of the time but not all of the time, so I describe them in terms of patterns. The Application Controller (379) is the mediator between the presentation and domain, and the Data Mapper (165) is the mediator between the data source and the domain. For organizing this book, I’ve described Application Controller (379) in the presentation section (Chapter 14) and Data Mapper (165) in the data source section (Chapter 10).

For me, then, the addition of mediating layers, frequently but not always useful, represents an optional extra in the design. My approach is to always think of the three base layers, see if any of them is getting too complex, and if so add the mediating layer to separate the functionality.

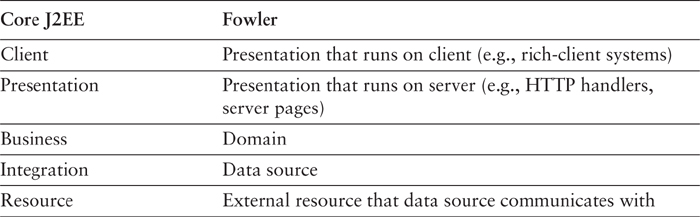

Another good layering scheme for J2EE appears in CoreJ2EE patterns [Alur et al.] (see Table 8.2). Here the layers are client, presentation, business, integration, and resource. Simple correspondences exist for the business and integration layers. The resource layer comprises external services that the integration layer connects to. The main difference is that they split the presentation layer between the part that runs on the client (client) and the part that runs on a server (presentation). This is often a useful split, but again it’s not one that’s needed all the time.

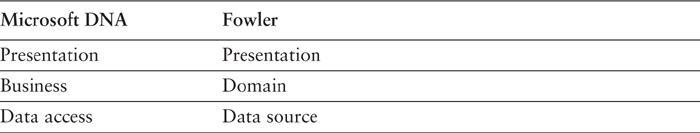

The Microsoft DNA architect [Kirtland] defines three layers: presentation, business, and data access, that correspond pretty directly to the three layers I use here (see Table 8.3). The biggest shift occurs in the way that data is passed up from the data access layers. In Microsoft DNA all the layers operate on record sets that result from SQL queries issued by the data access layer. This introduces an apparent coupling in that both the business and the presentation layers know about the database.

Table 8.3. Microsoft DNA Layers

The way I look at this is that in DNA the record set acts as a Data Transfer Object (401) between layers. The business layer can modify the record set on its way up to the presentation or even create one itself (that is rare). Although this form of communication is in many ways unwieldy, it has the big advantage of allowing the presentation to use data-aware GUI controls, even on data that’s been modified by the business layer.

In this case the domain layer is structured in the form of Table Modules (125) and the data source layer uses Table Data Gateways (144).

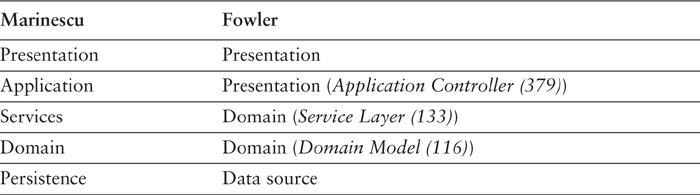

[Marinescu] has five layers (see Table 8.4). The presentation is split into two layers, reflecting the separation of an Application Controller (379). The domain is also split, with a Service Layer (133) built on a Domain Model (116), reflecting the common idea of splitting a domain layer into two parts. This is a common approach, reinforced by the limitations of EJB as a Domain Model (116) (see page 118).

The idea of splitting a services layer from a domain layer is based on a separation of workflow logic from pure domain logic. The services layer typically includes logic that’s particular to a single use case and also some communication with other infrastructures, such as messaging. Whether to have separate services and domain layers is a matter some debate. I tend to look at it as occasionally useful rather than mandatory, but designers I respect disagree with me on this.

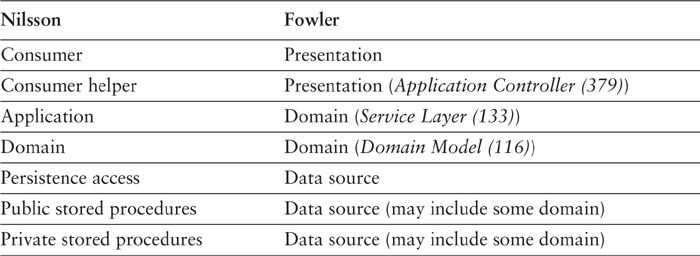

[Nilsson] uses one of the more complex layering schemes (see Table 8.5). Mapping to this scheme is made a bit more complex by the fact that Nilsson uses stored procedures extensively, and encourages domain logic in them for performance reasons. I’m uncomfortable with putting domain logic in stored procedures, as it can make an application much harder to maintain. On occasion, however, it’s a valuable optimization technique. Nilsson’s stored procedure layers contain both data source and domain logic.

Like [Marinescu], Nilsson uses separate application and domain layers for domain logic. He suggests that you can skip the domain layer in a small system, which is similar to my view that a Domain Model (116) is less worthwhile for smaller systems.