Whereas continental Europe was convulsed, first by the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Wars, Britain returned to canal construction once the Peace of Versailles had recognised American independence and ended the war with that country. Confidence was restored and money was once again available for investment. Speculators liked what they saw with the first generation of canals. Birmingham canal shares had started at £140 in 1767; by 1782 they were selling for £370 and ten years later they had shot up to £1,170. There was a very good reason for this. The Duke of Bridgewater had said that a good canal had ‘coal at the heel of it’, and that was exactly what this canal had and trade was booming, bringing in a healthy income from tolls. Now speculators thought of canal shares as quick routes to easy fortunes. If they could get in at the beginning of a new scheme, they had a good chance of selling the shares at a profit even before work got really under way. One commentator at the time described how they were prepared ‘to sleep in barns and stables, when beds could not be procured at the public houses’ so as to be on the spot when a new share issue was available. Another noted that they were even prepared to snap up shares before the Act had passed through Parliament. And in the early 1790s acts were being passed at an incredible rate: eight in 1792, twenty-one in 1793 and twelve in 1794. It is no wonder that these years came to be known as the years of canal mania.

Inevitably some schemes were complete duds that were never going to make a penny. The Oakham Canal is a case in point. Melton Mowbray had already been connected to Leicester and the new canal was to extend navigation to Oakham. It was never altogether clear where the traffic was to come from but the Act was duly passed in 1793. It was hardly a direct route. The modern road between the two towns is just 10 miles long; the canal stretched that to 15 miles. It started off by heading north from Oakham, before turning west towards Melton Mowbray. There was a long diversion around Stapleford Park, the estate of Lord Harborough, as the family did not want transport routes across their land. The canal company deferred to his lordship’s wishes. It never showed a profit and after just forty-five years it was bought up by the Midland Railway, which built over part of the route. That was one extreme. At the opposite end of the spectrum were canals such as the Grand Junction that was to form a vital part of a new main line between London and Birmingham and was later incorporated into the highly successful Grand Union Canal. The engineer for the latter was William Jessop, one of the new generation of civil engineers who followed on from Brindley with new ideas and new technology.

William Jessop sketched by George Dance in 1796, at the height of the canal mania years. He, more than anyone else, carried the burden of overseeing canal construction during the mania years of the 1790s as chief engineer on many of the most important projects of the day, both in mainland Britain and in Ireland. There is one other portrait of Jessop, still in possession of the family. Where two other great engineers, Brindley and Telford, chose to be painted with their most imposing canal works as a background, Jessop is shown here as a man of learning, with a handsome leather-bound volume at his elbow and indications of a more considerable library behind him. (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Jessop’s father was a shipwright who lived in Stoke Damerel, close to the Devonport dockyard. He was in charge of maintenance on the old wooden Eddystone lighthouse but when that caught fire during a terrible storm in 1755, Jessop joined John Smeaton in building the new, solid stone lighthouse. William was born in 1745 and in 1759 Smeaton took him on as an apprentice. It was the ideal start for a boy who was destined to become a notable engineer. He was soon involved in river navigation schemes, not as an apprentice but as an assistant. By 1772 he was working on his own and signing himself William Jessop, engineer.

His big chance came soon afterwards. Following the success of the Newry Canal, the most important project in Ireland was the Grand Canal, planned to join Dublin to the Shannon. It was on a grand enough scale to justify its name, with locks capable of taking 175 tonne barges. Work had started in 1756 under the engineer Thomas Omer, who was replaced in 1763 by John Trail. By 1770 a great deal of money had been spent, 20 miles had been completed but none of it was open for traffic. In 1771 the authorities decided to call in an outside expert and they approached Smeaton. The engineer agreed to come to Ireland for only one visit, but recommended ‘a young Gentleman who has just begun Business for himself, who has served me 13 years, viz. 7 years as an apprentice, and 6 years as an Assistant, and whom I have always found docile and intelligent’. Jessop’s fee would be one guinea a day, which was good news for the Company as Smeaton was charging them five guineas, plus a handsome travel allowance. Smeaton recommended a new line and Jessop surveyed the route over the Bog of Allen. At the same time there were problems on another Irish Canal that also needed to be looked at by the English engineers.

The Grand Canal of Ireland was proposed in the early eighteenth century, although work did not get under way until the 1750s. Progress was slow until Jessop took over and the whole main line, 82 miles from the Liffey in Dublin to the Shannon, was completed in 1804. Although as with many other canals its once lucrative cargo traffic has ended, it has become a popular tourist route. The canal here is shown passing through the heart of Dublin in what is now a very attractive area and the broad locks, designed to take barges, these days deal with trip boats and holiday makers.

The Newry Canal was supposed to cut the cost of coal in Dublin, but the cartage from the mines at Coalisland was higher than the rest of the journey by canal. An extension was supported by the church and promoted by the Archbishop of Armagh, who appointed one of his clergymen, Pastor Johnston, as engineer for the project. He had no experience and struggled with difficult conditions, especially the marshy land near Lough Neagh. In all the annals of canal construction it is doubtful if any canal ever made such slow progress. It was only 4 miles long and had just seven locks, but work that started in 1732 was only completed in 1787. Even then it failed to achieve its objective. There were four mines in the Coalisland area, two of which were easily accessed by the new canal. Unfortunately they were the least productive and the other two were only 3 miles away, but 200ft above the canal. There seemed no obvious solution to the problem, until a French engineer, Daviso de Arcot, a name usually anglicised to Ducart, appeared.

He proposed using small craft, unlike the large barges used on the rest of the canal. They would hold just one tonne each, but could be moved in strings. To overcome the difference in levels, he built three inclines, varying from 55ft to 70ft long. The boats could be lowered on these over rollers. This sounds like the system used on the Grand Canal in China, and it was a system already in use in Europe, which is probably where Ducart got his idea. Smeaton, on his trip to Europe in the 1750s, had seen schemes in the Netherlands, known as ‘windlasses’, where slopes with rollers moved vessels from one dyke to another at a slightly different level. Ducart had travelled in Europe, looking at canal works there and may have seen such systems.

The Coalisland incline was not a great success as the boats kept sticking, and Jessop recommended using a double track and extending the length of the boats. By 1790, however, according to William Chapman who wrote a treatise on canals, published in 1797, the system had been changed. Now there were two tracks and the boats were floated onto cradles, which was the basis for many inclined planes in the canal age. There is no evidence to confirm this, but Jessop might take the credit for introducing the system to Britain. It was not new as far as Europe was concerned. A similar system had already been built at Fusina near Venice. The Brenta river was separated from the Venetian lagoons by a dam, and the incline had been built to get round it. A horse gin moved the vessels along a railed track. Gins such as this were commonly in use in mines for moving material up and down shafts. The horse, walking a circular track, moved a drum around which the rope was wound.

Over the next few years, Jessop gained more experience as an engineer in his own right on important river improvement schemes, including the Calder & Hebble Navigation. But it was with renewed activity in canal construction that he came into his own. His first major work was the Cromford Canal, authorised in 1789. This joined the Erewash at Langley Mill and was carried through a rich mining area to Cromford where it had its terminus close to Sir Richard Arkwright’s pioneering cotton mill. Jessop himself described the area through which the canal was to pass as ‘rugged and mountainous’, adding that ‘it will at first sight strike an observer as very ineligible for such a project’. One can only agree. Although the canal was only 14½ miles long, there were four tunnels, one of which, the Butterley tunnel, was 2,966yd long. There were also two major aqueducts: one over the Amber and the other over the Derwent. As if that was not enough, there were problems with water supply, so three reservoirs were also needed. Faced with so many problems, Jessop planned a composite canal: the section from the Erewash to Butterley tunnel would be a broad canal, capable of taking 14ft beam barges, but the long tunnel would be just 9ft wide and the remainder of the canal to Cromford would be narrow.

The building of the canal brought out one of Jessop’s most endearing characteristics. He was the man in charge and if things went wrong, he always accepted full responsibility. He had troubles with both the aqueducts. Part of the Amber aqueduct collapsed and Jessop personally paid for the repairs. Then in 1793 a crack appeared in the Derwent aqueduct and it became clear that the walls were not thick enough, and again Jessop footed the bill. In a technical sense he was to blame, but this was complex engineering work and the budget was never big enough to do a thorough job. He had economised in his use of materials on the aqueducts but had gone too far. Needless to say, the financiers did not consider it was their responsibility. His work on the Cromford Canal may have hurt Jessop’s pocket, but it did wonders for his reputation. He was seen both as a good engineer and an honest man. Just as Brindley had been the man everyone wanted to employ in the early years of canal building in Britain, now it was Jessop who was in demand all over the country. He was also about to return to Ireland.

Butterley tunnel on the Cromford Canal was 2,996 yards long, and built to unusually small dimensions, just 9ft wide and 8ft high at the crown. There was no towpath and boats had to be legged through, as seen here, by walking the boat along with their feet against the sides of the tunnel. It was built by sinking a total of thirty-three shafts, from which the men could work out in either direction, as well as working inwards from the two ends. The tunnel was literally undermined by a nearby colliery and was severely damaged: by the 1920s it was impassable and was never reopened. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

Progress on the Grand Canal was slow. The high ambitions of 137ft by 20ft locks proved impractical and far too expensive; this was later reduced to 80ft by 16ft and then Smeaton recommended an even greater reduction to 60ft by 14ft. Jessop was called in as a consulting engineer at least as early as 1789, since in a letter of 1790 he told the authorities he would be coming over ‘for two or three months as formerly’. He eventually standardised all the locks at 63ft by 14ft. The greatest problem he faced was crossing the great peat morass, the Bog of Allen. To gain firm enough ground to hold a puddled channel, he had to build drainage ditches to either side, and his experience in drainage work in the English Fens must have come in useful here. It took five years to complete the canal across the bog, but the results were not entirely successful: there were frequent problems with the collapse of the clay banks. It was finally completed in 1804. By this time, Jessop had been at work on major canal schemes in mainland Britain.

The Derwent aqueduct carries the Cromford Canal across the river. It caused trouble in the early years and when cracks appeared in 1793 it had to be reinforced with iron tie bars. The building at the far end of the aqueduct is the Leawood Pumping Station, built in 1849 to bring water up from the River Derwent to feed the canal. The Cornish beam engine is still in there, has been restored to full working order and is regularly steamed by volunteers on open days. This section of the canal, between here and Cromford, is still open. (Anthony Burton)

The canals that crossed the Pennines served areas that were developing important textile industries: mainly woollens in Yorkshire and cotton in Lancashire. The Huddersfield Narrow Canal had Britain’s longest canal tunnel at 3 miles 135 yards, but it also needed a steady processions of locks: forty-two on the Huddersfield side and thirty-two to Ashton-under-Lyne. The photograph shows the canal between Marsden, at the eastern end of Standedge tunnel, and Huddersfield. With so many locks, reservoirs were essential, and one can be seen to the left of the lock. To the right is the mill pond that served the large woollen mill. The canal was derelict for many years but has now been fully restored. (Anthony Burton)

The first canal designed to cross the Pennines was the Leeds & Liverpool, already mentioned in Chapter 5, but in the 1790s it was still far from complete. It had avoided the obstacle presented by the range of hills by taking a huge sweeping curve to the north. In 1794 an act was passed for a more direct route, the Rochdale Canal, that would link the Calder & Hebble navigation at Sowerby Bridge with the Bridgewater Canal in Manchester. The first plans had been drawn up by John Rennie. It was to be a canal on a grand scale with locks taking vessels 14ft 2in by 74ft and with an immense 3,000yd long tunnel through the Pennines at the summit. Rennie did not stay with the project and it was passed to Jessop, who wanted nothing to do with creating such a tunnel. Instead his canal was to have ninety-two locks in just 33 miles and was to cross the summit in a deep cutting. With so many locks, and only a short summit level, the biggest problem would be water supply. Jessop put in hand two immense reservoirs at Hollingsworth and Blackstone Edge but a third had later to be added. It is easy to admire the engineering that produced two vast watery staircases spanning the Pennine Hills, but creating the reservoirs was no less impressive. The Hollingsworth reservoir, for example, is contained behind a vast bank, 10ft wide on the top and sloping in a 1:2 ratio to its base. At its heart is a 9ft thick core of puddle clay.

There was to be one other direct route through the Pennines, whose engineer was Benjamin Outram. He became a partner with Jessop. During the building of the Cromford Canal, large iron ore deposits were found and Jessop and Outram formed the Butterley Iron Works to take advantage. Outram, it seems, did not share Jessop’s distaste for Pennine tunnels. The Huddersfield Narrow Canal – the name distinguishes it from an earlier broad canal that it joined in Huddersfield – was authorised in 1794. It too was heavily locked: thirty-two on the Lancashire side, forty-two in Yorkshire. In between was Britain’s longest tunnel. Standedge tunnel is 3 miles 135 yards long, a narrow opening without the benefit of a towpath. The difficulties in creating this exceptionally long tunnel were immense. Four steam engines had to be erected on the rough moorland above the canal to pump out water during construction. Anyone walking over Standedge Moor today can see the remains of one of the engine houses and the vast heaps of spoil hauled up from the various shafts. The canal finally opened in 1804, held up less by technical difficulties than the company running out of money. As with the Rochdale Canal, the Huddersfield needed reservoirs to serve the long strings of locks. Ten were built high on the moors but the earth banks frequently leaked. In 1799 there was a far more serious breakage in the Tunnel End dam that sent water crashing down the Colne valley at Marsden causing huge damage and halting work on the canal. The company had to go back to Parliament to get a new act to raise extra money to continue the work. Later another reservoir was built on Marsden Moor and on the night of 29 November 1810, the dam wall collapsed. It became known as the Night of the Black Flood. The Colne Valley was again inundated and this time not just property suffered: six people died.

In 1793 Jessop himself was put in charge of the most prestigious canal scheme in Britain – the Grand Junction. It was to form a new, direct link between Birmingham and London, running from a junction with the Oxford Canal at Braunston to the Thames at Brentford, with an additional, lock-free branch to Paddington. Few canals demonstrate the changes that had occurred between the age of Brindley and the new era of men like Jessop. At first the canal from Brentford takes an obvious route following the course of the River Brent. But where earlier engineers might have staggered the locks along the valley, Jessop grouped most of them in a flight of six at Hanwell. The canal climbed steadily to a point more than 300ft above the tidal Thames and there it reached the line of the Chiltern Hills, stretching right across the route.

The canal had been built as a barge canal, taking vessels up to 14ft 3in. This represented a considerable obstacle, since a tunnel would need to be wide enough to accommodate them. There was no question of going over the top, so Jessop opted for a third alternative. The canal would dive through the hills in a deep cutting at Tring. This was to be a mile and a half long and, at its deepest point, the edge of the cutting would be more than 30ft above the bed of the canal. Nothing on this scale had ever been attempted and one reason that it was practical was a large workforce experienced in canal cutting. They were originally known as navigators, men who dug the navigations, but this was soon shortened to the more familiar navvy. These were specialist workers, with no permanent home, who travelled from canal working to canal working, where their services were needed – and where the best rates were paid. An experienced navvy could shift about twelve cubic yards of earth a day, but even with their prodigious strength it needed an army of men to complete Tring. The work required the men to move more than half a million cubic feet of material, very little of which would be easily worked soft soil. At the height of the construction period, there were some 10,000 navvies at work at Tring.

The Grand Junction Canal, now incorporated as part of the Grand Union Canal, was one of Britain’s most successful waterways. It was the major link in a through route, connecting Birmingham and the manufacturing districts of the Midlands to London. Many industrialists built canalside factories to make use of its facilities, both to bring in raw materials and send out finished products. The Ovaltine factory was established at King’s Langley in the early twentieth century and ran its own fleet of narrow boats. (Anthony Burton)

Deep cuttings called for a new technique. It would have been impossible just to push barrow loads of soil straight up to the top of the cutting, so barrow runs were introduced. These consisted of steep sloping planks laid on trestles up the cutting slopes. Barrows could be pulled up by horses at the top, but the men had to walk up behind the barrows to keep them on the planks. One can imagine what the barrow runs must have been like, covered in wet clay and dirt, and just how easy it would be for a man to lose his footing. If he did, he had to drop the barrow off to one side and throw himself off in the opposite direction to avoid being buried under the heavy spoil. Coming down, he ran down the planks, pulling the empty barrow behind him. There are no known illustrations of canal barrow runs, but a generation later Robert Stephenson built the London & Birmingham Railway. His route closely followed Jessop’s and he too opted for a deep cutting at Tring. Contemporary illustrations show the barrow runs, looking much as they must have done in Jessop’s day.

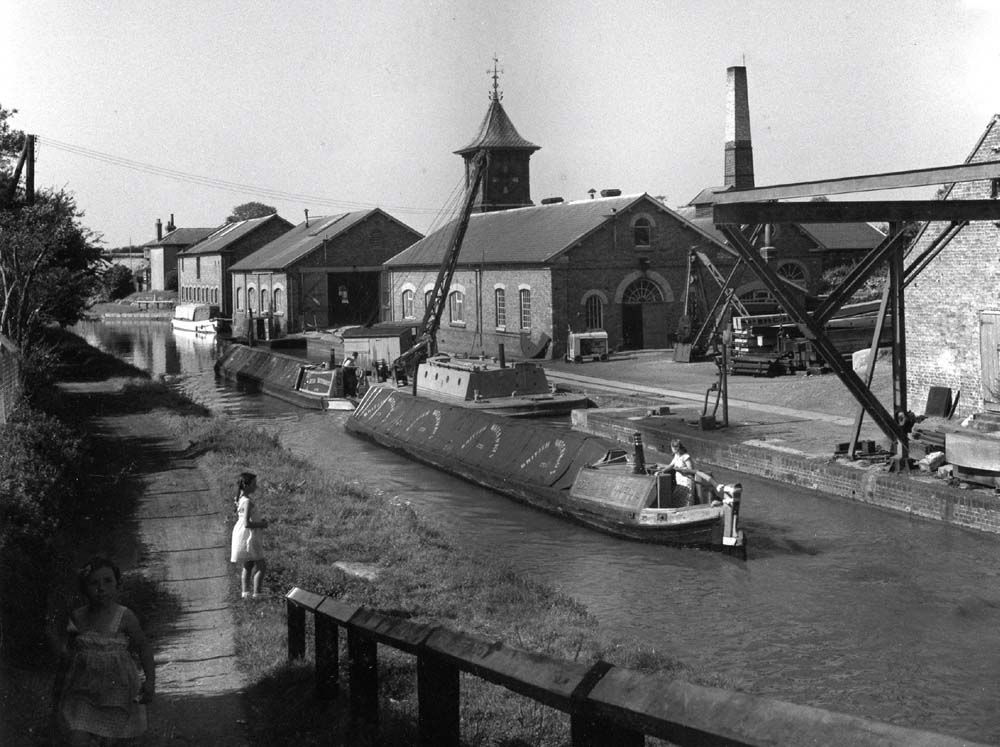

The Tring cutting lies at the summit of the canal, so this was an important site. The first essential was to supply it with water, which was originally planned as coming from springs near Wendover. As a channel had to be cut anyway, it was made into not just a conduit but also a navigable arm for the main canal. In time, this proved inadequate and three reservoirs had to be built. With so much going on at this point it seemed sensible to build a maintenance yard here at the northern end of the cut. Bulbourne Yard remains much as it was in Jessop’s day, at least externally. Even when one goes inside the building it still has its traditional blacksmith’s forge.

The Grand Junction had its own maintenance yard at Bulbourne at the northern end of the Tring cutting. They produced both wood and ironwork, including new lock gates (see illustration p.30). (Anthony Burton)

Jessop needed to provide aqueducts for the new canal, which we shall look at in the next chapter, but his most difficult task came with the building of two tunnels: the 2,042yd one at Braunston and the even longer 3,056yd Blisworth tunnel. Contractors had failed to meet the standards set by the engineer, but there were difficulties that had not been allowed for. At Braunston, the workers found quicksand that had not appeared in the test borings. Work on Blisworth dragged on for years. These were tunnels on a large scale, wide enough to take either barges or to allow two narrow boats to pass each other. At Blisworth, work was carried out from nineteen shafts as well as from the two ends. Both tunnels had to be lined with brick, but this was not an age where you simply ordered the material from a brickyard. They were made on site: the clay was dug, shaped and fired in temporary kilns. The results were not the uniformly shaped and coloured bricks you would find on a modern site. Colours varied enormously, depending on where the bricks had been placed in the firing, and this only adds to the charm of even the simplest of structures on eighteenth-century canals.

One of the most difficult undertakings on the Grand Junction Canal was the construction of the 3,057 yard long Blisworth tunnel. It was built to far more generous dimensions than the Butterley tunnel (p.81), 16ft 6in wide with a crown 11ft above water level. It was lined with brick, but had no towpath, so as at Butterley, boats had to be legged through. Because of the width, the only way men could reach the tunnel sides was to lie on wings – boards projecting on either side of the boat. For many years, professional leggers were employed. By the early twentieth century, when the tunnel had been open for a hundred years, it needed extensive reconstruction. Here, the workers pose for their picture on completion of the work in 1910. It gives a good idea of the size of the tunnel, and the tools the men hold indicate that the work still depended largely on manual labour. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

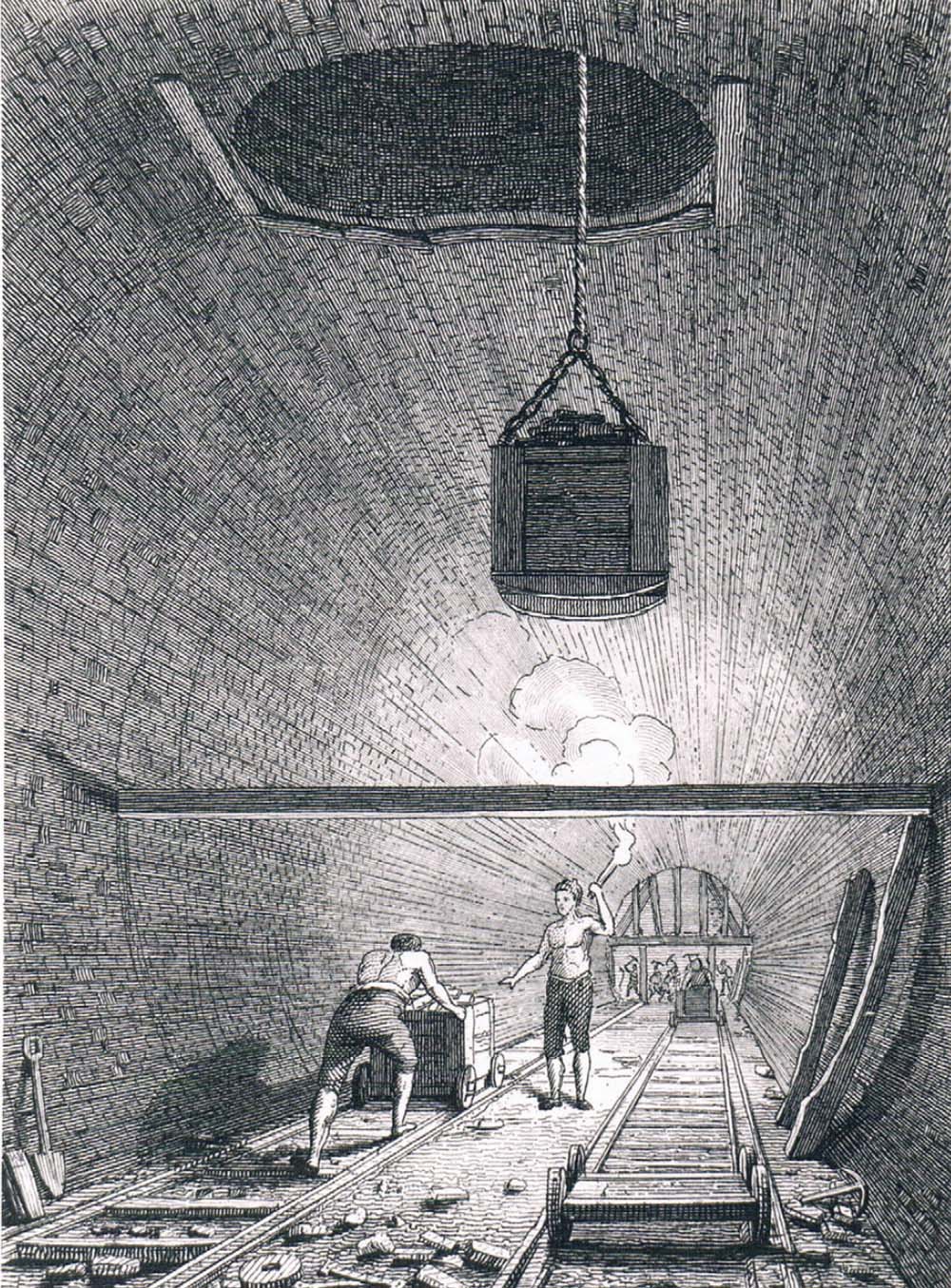

The Grand Junction Canal entered the Thames at Brentford and boats heading for the Port of London continued the rest of the journey by river. There was also a branch to Paddington. In 1812 work began on an extension of the Paddington Arm, the Regent’s Canal that passed through north London to enter the Thames at a new dock complex at Limehouse. It involved building a tunnel at Islington, and this illustration appears to be the only one produced, showing a canal tunnel under construction. In the distance, men work with pickaxes at the face, and the wooden centring for construction of the brick arched roof can be seen just in front of them. A box is being lowered or raised in the shaft. These boxes could be used either to bring down essential material, such as bricks, or to remove spoil. The boxes could be fitted onto simple bogies that were moved along the temporary railed tracks. (Waterways Archive Gloucester)

Contemporary illustrations of actual canal construction are very rare, but there is one showing work in progress on the Regent’s Canal tunnel at Islington. In the distance, one can see workers at the face of the tunnel with pickaxes. Immediately behind them is wooden centring on which the brickwork arch for the tunnel will be formed. In the foreground, a large wooden crate of spoil is being raised up a shaft, while another crate on a four wheeled trolley is being pushed along one of a pair of wooden tracks. The whole scene is lit by a man holding a flare who, like all the others, is stripped to the waist. There is also physical evidence on other canals of how tunnels such as Blisworth were built.

One of the most unusual tunnels is at Dudley on the canal linking the main line of the Birmingham Canal to the Staffs & Worcester. It began in 1775 as Lord Ward’s Canal to link the Birmingham Canal to a complex mine system under Castle Hill. It was then extended between 1784 and 1792. In places it opens out to cavernous vaults; in parts it is brick-lined, low and narrow, but in other parts the bare rock is exposed. It is here that you can still see semi-circular grooves in the rock face. These are what remain of holes drilled by hand into the rock, filled with gunpowder that after it exploded left this telltale sign, showing the point where rock has split away.

The Grand Junction opened in 1805 and was an immense success. Not all Jessop’s projects are as well known as this, but some demonstrate why the canals of this period were different from their predecessors. The canals of the mania years not only brought in a new generation of engineers but also a change in technology. Where the first canals of the Brindley era had crept across the landscape, squirming round hills and valleys to keep on the level, the second generation of canals had taken a much bolder approach. This can be seen very clearly on what is now a largely abandoned and forgotten waterway – the Barnsley Canal. Although a comparatively short canal, just 11½ miles long, it needed a great deal of engineering work. There are fifteen locks, designed to take barges up to 78ft long and 14ft wide. The canal also had to cope with a high ridge running right across the route, which Jessop carved through in a deep cutting, the spoil of which was then used to build up an embankment that strode across the next valley –the technique of ‘cut and fill’.

Jessop was not the only notable engineer at work during the early 1790s. John Rennie’s background was different from that of Jessop and even less like that of Brindley. He was born at Phantassie in Scotland in 1761. His father was a farmer and owner of a brewery. The young Rennie was interested in all things mechanical, and learned the craft of millwright from another remarkable man, Andrew Meikle, inventor of the threshing machine. He combined this practical experience with studying at Edinburgh University. Scottish universities were far ahead of their English counterparts in offering studies in the sciences, and Rennie was scathing of the English system, as his son, Sir John Rennie, himself a distinguished engineer, reported in his autobiography:

Looking down on the deep cutting on the Barnsley Canal. Scattered along the bank are great blocks of sandstone, giving a good idea of the conditions the engineers faced in constructing the cutting. The stone would be drilled by hand and the holes filled with gunpowder to blast the rocks apart. All the material would then have been cleared away by hand and taken away in carts to build an embankment. (Museum of London)

‘ My father wisely determined that I should go through all the graduations, both practical and theoretical, which could not be done if I went to the University, as the practical parts, which he considered most important, must be abandoned: for he said, after a young man has been three or four years at the University of Oxford or Cambridge, he cannot, without much difficulty, turn himself to the practical part of civil engineering.’

Rennie’s skill as a millwright brought him to the attention of the famous Birmingham industrialist, Matthew Boulton, who put him in charge of building the immense Albion Corn Mill on the Thames in London. The city saw his greatest triumphs, including work on new docks and the design for three bridges: London, Southwark and Waterloo. Rennie would be astonished that his London Bridge is now a tourist attraction in Arizona.

John Rennie was an engineer known as much for his elegant designs as for his technological abilities. This was shown very clearly on the Kennet & Avon Canal. It began at the western end, joining the navigable Avon at Bath. It passed right through the fashionable Sydney Gardens, where its impact was reduced by running in a cutting, crossed by this delightful iron bridge. (Anthony Burton)

The most attractive of all the structures designed by Rennie is the Dundas aqueduct that carries the Kennet & Avon across the Avon. Perhaps the inspiration came from the buildings of nearby Bath, for the theme is purely classical. Pilasters ornament the spaces between the arches, and the whole structure is topped by a deeply dentilled cornice and ornate balustrade. It was built from Bath stone quarried locally, a form of limestone that has a rich, creamy colour and adds immensely to the beauty of the scene. (Anthony Burton)

His bridges were widely praised for their elegant design, and the same could be said of his aqueducts. He showed a fine sense of proportion, an understanding of classical architectural language and an awareness that different locations needed very different treatments. This is exemplified in his two finest works: Dundas aqueduct on the Kennet & Avon Canal and the Lune aqueduct on the Lancaster. The former, just 5 miles from the start of the canal in the centre of Bath, is as elegant as anything that city offers. Built of the lovely honey coloured dressed Bath stone it strides over the River Avon in a single arch, with two smaller arches on the land at either side. The structure is ornamented by pilasters between the arches and topped by a deeply dentilled cornice and balustrade. The five-arched aqueduct over the Lune in Lancaster uses a similar classical language but more robustly, and the dark stone, instead of being dressed to a smooth finish, is rough-hewn.

Extensive records have survived of work on the Lune aqueduct and the problems encountered by the builders. Similar stories could probably be written about all the great stone aqueducts built in the country at this time. The engineer on the spot was Archibald Millar, who had already gained considerable experience working with Smeaton in Ireland. The first thing to be done was to settle the key men on the site, including a Mr Exley, Millar’s principal assistant. Millar ordered the construction of temporary accommodation and workshops, with a saw pit, carpenter’s shop, store room, a kitchen and a room for Exley. The latter was to be floored and have a fireplace, but Millar noted that it was all to be done on ‘the most frugal plan’. Exley shared his kitchen with ‘the Steam Engine man’, which must have been trying as the records show that he was often drunk – one report noted ‘he has kept the can to his head for 3 or 4 days’.

The first stage of building involved the construction of coffer dams, watertight wooden enclosures, built up by driving piles into the floor of the river. Once completed, the area contained by the piles could then be pumped dry so that men could work inside it, building the foundations for the piers. The crude pile-driving machines were hand operated. It was hard work and dangerous: one unfortunate man lost three fingers when the ram fell on his hand. The coffer dams were never completely clear of water, no matter how much was pumped out by the steam engine, and the men worked in terrible conditions. This was not an age where employers showed great sympathy for any workforce, but the conditions were so bad that Millar recommended giving the men ‘some small sum’ daily for drink.

Once the piers had risen above water level, building the arches could begin. The wooden framework was constructed by men under the control of the master carpenter, who was also foreman for the whole site. It was hauled into place above the piers and simple cranes erected to lift the heavy blocks of stone into place. Once the keystone was set in the centre of the arch, the centring could be removed. The whole site was teeming with workers – masons, carpenters and navvies. In summer 1794 there were more than 150 men at the Lune site. By the time the aqueduct was completed in 1796 the construction bill had risen to £48,000, roughly £5 million today, which makes it seem a real bargain. There was comparatively small outlay in capital equipment and labour was cheap – the highest paid worker on site, the foreman, only got about £5,000 a year at today’s prices and ordinary workmen a good deal less.

Apart from the aqueducts, Rennie’s canals, particularly the Kennet & Avon, are good examples of how canal work was advancing in the 1790s. Like Jessop, Rennie kept his locks grouped in long flights. The canal rose from the Avon in Bath via a flight of seven 14ft-wide locks – later reduced to six when two were amalgamated into one rather frighteningly deep lock. From the top of the flight the canal is lock free for nearly 10 miles. This flight is insignificant compared with the twenty-nine locks at Caen Hill that carry the canal up to Devizes. To conserve water, the locks have side ponds terraced into the hillside beside them that act as individual reservoirs. Even with water-saving devices, there was still a need for extra supplies for the long pound between the top of Bath Locks and Bradford-on-Avon and for the short actual summit. Rennie provided two different solutions to the problem.

By the time the canal had climbed to the first long pound, it was some 50ft above the River Avon. There had been an old watermill at Claverton and Rennie used this site to create a pumping station to lift the river water into the canal. Power was supplied by an immense pair of coupled water wheels, each 15ft 6in diameter and 11ft 6in wide. Through gearing these worked a pair of beam pumps of the type familiar from the steam engines of the day. The system could lift 100,000 gallons an hour. They have long since been replaced by a modern pumping system, but when the new engine failed in 1989, the old pumps ably took over the task, just as they had done nearly two centuries before.

On the other site, Rennie used the latest technology. James Watt had improved on the older Newcomen engines. He no longer relied on air pressure to force a piston down in a cylinder. He still condensed the steam, but now in a separate condenser. The cylinder no longer had to be reheated at every stroke, but could be kept permanently hot, with a closed top and lagging round the perimeter. Instead of air pressure, steam pressure acted on the opposite side of the piston from the vacuum. He had partnered with Matthew Boulton, and a Boulton and Watt engine was installed at Crofton in 1812, one of a pair that lift water from a lake to the summit level. The 1812 engine is now the oldest steam engine in the world, still in its original engine house and still capable of doing the job for which it was built. Claverton shifted 100,000 gallons an hour, whereas Crofton manages 250,000 gallons. In their day, canals such as this were at the forefront of technological development.

The steam engine was at the heart of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, no longer used just to pump water from mines, but as the prime mover for mills and factories. Canals played a vital role in supplying the coal that kept them going. But the age was also about new materials, and this branch of technology had a profound effect on how waterways were developed at the end of the eighteenth century and beyond.