10

Political Ambiguity in Recent Cold War Spy Stories on Screen

Cheryl Dueck

Film, itself a medium of surveillance, is arguably an ideal site for the aesthetic depiction of surveillance mechanisms. A number of films in the second decade of the twenty-first century have effectively employed these aesthetics as a conduit for national stories to travel internationally and thus contribute both to discourses about Cold War surveillance and to those about the current climate of “liquid surveillance” (Bauman and Lyon 2013). As David Lyon puts it, today’s surveillance “not only creeps and seeps, it also flows. It is on the move, globally and locally. The means of tracing and tracking the mobilities of the twenty-first century are ‘going global’ in the sense that connections are increasingly sought between one system and another” (2010, 330). The Edward Snowden revelations of 2013 brought attention to the vast scope of National Security Agency activities worldwide and, in turn, served to reframe representations of Cold War surveillance. As explored here the films about the Cold War in the subsequent years engage more explicitly than previously with a current international preoccupation with blanket surveillance in their aesthetic approach, their thematic content, and their application of pluri-medial networking. My analysis of the feature films Westen (West; Schwochow 2013) and Bridge of Spies (Spielberg 2015) and the television series Deutschland 83 (Winger and Winger 2015) will show how these productions undertake to present political ambiguity through filmic devices such as blurring, framing, and representation of affect, as well as narrative, thus speaking to the climate of fear and mistrust of all mechanisms of surveillance.

We live in a heightened era of surveillance anxiety, in which we have learned that the CIA uses camera devices in phones and televisions to spy on people. Indeed, when President Trump’s advisor and spokesperson mistakenly told Americans that even their microwaves could be watching them (Timberg, Dwoskin, and Nakashima 2017; Kelly 2017), many likely accepted it as fact. Who is watching whom and why? Since the beginning of cinema, the act of looking has been a preoccupation of filmmakers, a built-in reflexivity. With this in mind, then, spy films are a natural fit and speak to each audience with their own timely concerns about watching and looking. Cinematography and staging are key elements that convey to the viewer the anxieties and motivations of watchers and watched. This chapter will address the Cold War espionage that has featured prominently in film and television of the second decade of this century, not as historical representation but as an engagement with more-contemporary preoccupations with blanket surveillance. In Germany public debate over communications surveillance and protection rose sharply in 2012, as citizens learned that the Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst, BND) had been monitoring tens of millions of emails (“Geheimdienste überwachten” 2012). Since Snowden’s revelations in 2013 of the extent of the U.S. National Security Agency’s reach internationally (Poitras, Rosenbach, and Stark 2013), from laptop cameras to German chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone (“Merkels Handy” 2013), international anxieties about surveillance have been at front of mind. Lyon defines surveillance as “collecting information in order to manage or control” (2015, 3). The collection of information by agents that took place during the Cold War had, for the most part, a clear purpose: to understand the activities of an enemy state in order to prevent harm, or to avert counterrevolution from within the state. Surveillance was carried out by individuals on individuals. Lyon explains further that surveillance involves “systematic and routine attention to personal details, whether specific or aggregate, for a defined purpose,” and this purpose is “to protect, understand, care for, ensure entitlement, control, manage or influence individuals or groups” (3). While this purpose and definition apply equally well to Cold War and current surveillance practices, the means of surveillance have changed, and the anxieties shifted.

A significant difference between Bond-style spy thrillers and films about surveillance in state socialism is, of course, that the Bond-style agents are carrying out surveillance of an enemy state. Creating empathy with a spy who is serving one’s own national interests by protecting against a foreign enemy differs from when the enemy is his or her own people. Since the spy may come from within, the spy thrillers that involve internal state surveillance speak compellingly to contemporary anxieties about the kind of “liquid surveillance” that is conducted worldwide through digital monitoring.

Liquid Surveillance in Cinema

The term “liquid surveillance” derives from conversations between Zygmunt Bauman and David Lyon, first used in publication in 2010 (Lyon) and subsequently in a book-length record of their exchanges on the subject (Bauman and Lyon 2013). Bauman’s long-standing occupation with surveillance branches out from Foucault’s use of the prison panopticon as a metaphor for the power relations of surveillance: a form of self-monitored behavior control contingent on the knowledge that one could be observed at any time by an unseen inspector. In this model there remains a relationship between the watcher and the watched, and the model aims to provide transparency to the watcher and eliminate ambivalence (Lyon 2010, 329). We are now, according to Lyon and Bauman, in a postpanoptical environment, in which those with surveillant power “can at any moment escape beyond reach—into sheer inaccessibility” (Bauman 2000, 11). In liquid modernity change is permanent: structures of the social world are in a condition of constant mutation and are no longer “solid” (Bauman 2000). Connections that have been made are readily severed, identities change, and expectations give way to uncertainty, which means that citizens subject to mass data surveillance may easily become suspects:

Because of the way that personal data are used, everyone living in so-called advanced societies is routinely targeted and sorted by numerous organizations on a daily basis, whether applying for a driver’s license, paying a telephone bill or surfing the internet. The concept of liquid surveillance captures the reduction of the body to data and the creation of data-doubles on which life-chances and choices hang more significantly than on our real lives and the stories we tell about them. It also evokes the flows of data that are now crucial to surveillance as well as to the “time-sensitivity” of surveillance “truths” that mutate as more data come in. (Lyon 2010, 325)

The flows move in all directions, in turn eliciting “liquid fear,” Bauman’s term from 2006. The constant mutation of information means that attempts to eliminate ambivalence, or blurred lines, are doomed to fail.

Rapidly flowing images and heightened anxiety are signatures of a good thriller, and all three of the works discussed here fall into the thriller genre: two as feature films, the other as an eight-episode television series. Their plot structures are designed for suspense and enjoyment and to attract diverse international audiences. They vary in the extent to which the historical events depicted are part of a contextualization or didactic purpose, but all make efforts to provide high style diversion. Set in the Cold War, with involvement of East and West Germany, the Soviet Union and the United States, all of them move across East-West borders and provide views of both sides that shift preconceptions of the truths that governments believe they can gain through surveillance. In each case the story is driven by the pervasive question, “who is watching?”

Continuities in Post–Cold War Surveillance and Espionage: Schwochow’s Westen

Westen is a film by director Christian Schwochow, with a screenplay by his mother, Heide Schwochow. It is based on a bestselling novel with the title Lagerfeuer (Campfire) by Julia Franck (2003), who also assisted with details as the Schwochows worked on the screenplay.1 It premiered at the Montreal World Film Festival in August 2013 and was released more widely in 2014, timed to coincide with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, on November 9, 2014. The film, which received several awards at the German Film Awards and the Montreal Film Festival, tells the story of Nelly, played by Jördis Triebel, a woman who decides to go West with her son, Alexei, in the late 1970s: so-called Republikflucht (flight from the Republic). Nelly is a professional chemist, and Alexei’s father, Vassily, was a Russian physicist who traveled often. The film begins with his departure for a conference in the Soviet Union, from which he never returns. She is told that Vassily died in a crash, but his body has mysteriously never been found. Opting for a fresh start in the West, she hires a Western smuggler, who takes her and her son across the border on the pretense that they are getting married. The action is set primarily in the Marienfelde Refugee Transit Centre in West Berlin for a period of months in the late 1970s, where the protagonist is subject to extensive questioning by the CIA and the West German BND, as a potential security risk. An African American CIA agent, John Bird, finds her attractive, and after they begin a discreet sexual relationship, she is able to elicit from him the reason for the intense scrutiny: The Americans believe that Vassily was an agent whose role was to recruit Western scientists, and the West Germans may have faked his death to get him out when he wanted to distance himself. That would mean that he could still be alive and now rogue in the West, and she would be an observation target for the Stasi to track him down. When asked why she left the East, she draws a comparison between the interrogation and surveillance by the Americans and the West Germans with that of the State Security Service (Stasi) in East Berlin: “I’ll tell you why I wanted to leave East Germany. Because of questions like these, which insinuate, attack, and keep breaking open old wounds.” The film emphasizes a continuity of experience: the similarly bleak cityscape on both sides of the border, the unsettled movement of the camera, and the conspicuous angles with which it “watches” her activities lend an air of constant anxiety to the film. She has difficulty getting work, since the employment assistance office disregards her profession as a chemist with a doctorate, and her son is bullied at school for his East German appearance and different behavior. By the end of the film, she has exited the camp, and set up an apartment and a Christmas tree for her and her son. The film concludes with the camera peering at her brightly lit window from the outside, and we are left wondering who is watching. The mystery of the husband is never resolved—could it be Vassily watching? The BND? The CIA? We don’t know, just as those living through it at the time did not know.

A Question of Loyalty: Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies

A big-budget film directed by Steven Spielberg, Bridge of Spies is set further in the past and is based on a historical episode in 1957, in which the lawyer James Donovan served as defendant for the KGB agent, Rudolph Abel, whom the CIA apprehended in New York City. After the Soviets shot down CIA agent Gary Powers’s plane in 1960 and then captured him, Donovan was an unofficial government delegate who assisted in the arrangement of a prisoner exchange at the Glienicke Bridge in East Berlin. The opening scenes lead with the character study of Abel, whose cover is as a struggling artist with his easel on the river walk, as he transfers a coded message with the aid of a hollow coin. Soon after we see FBI agents in trench coats and fedoras in hot pursuit, preparing to take him down. Abel gains the audience’s empathic response when he is able to evade the agents, walking right past them as he exits the crowded subway station: we are on the side of the Soviet spy from the first moments of the film. Mark Rylance compellingly plays Abel as modest, soft-spoken, and clever. When the agents do catch up with him in his studio, he is able to destroy the coded message with paint, on the pretense of cleaning his palette, and the narrative focalization remains with him as the agents scour the modest room for evidence. The subjective agency lent to Abel is, in effect, mirrored when James Donovan is introduced to the narrative as a principled attorney. His field is now insurance law, but he has been tapped for Abel’s defense because he was a prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials and knows criminal law. Although reluctant he adheres to the value of the American justice system that everyone deserves a fair trial and legal representation. Played by Tom Hanks, Donovan begins his defense of the KGB spy with the argument that Abel can’t be accused of being a traitor” since he was loyal to his own state. The narrative mirroring recurs when Gary Powers enters the story, portrayed as a naive yet patriotic CIA agent assigned with a small team to a top-secret mission: to fly deep into Soviet territory with the new high-altitude surveillance aircraft—the Lockheed U2—equipped with powerful camera equipment. The commanding officer instructs the agents that they are in no circumstances to fall into enemy hands and gives them each a lethal poison pin inside a silver dollar, for an efficient suicide in the case of impending capture. When the plane is shot down and Powers does not use the pin, his U.S. military superiors consider this an instance of personal failure, inferior in the film’s narrative to his Soviet peer. In the second half of the film, when Donovan secretly brokers negotiations for the trade of Abel for Powers in East Berlin, and political machinations of Soviet–German Democratic Republic (GDR) relations enter the fray, the ambiguity established early on devolves into characterization of Eastern Bloc politics as clownish and lacking sophistication. The film, though it concludes with an emotive endorsement of the American justice system and a heroization of the free individual in a democratic society embodied by Donovan, draws a parallel early on between the techniques employed by the CIA, the KGB, and the Stasi. The film is narratively structured to maximize the symmetry of the characters and systems: at the midpoint of the script (Charman, Coen, and Coen 2014, 50), a news bulletin announces the Powers crash and the Supreme Court conviction of Abel on the same day. The focalization of Abel and Donovan’s recognition of his individuality and honor counters the demonization of the Soviets that is dominant in the American culture of the time and muddies the waters of political allegiance.

Sympathizing with the Spy: Anna and Jörg Winger’s Deutschland 83

Deutschland 83 is a TV series set in Germany in 1983, as the title indicates, a year of intense nuclear tension. Our protagonist is a reluctant East German spy for the HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung [Main Intelligence Directorate]), reassigned from his border-guard duty to infiltrate the office of West German Bundeswehr general Edel at a missile base. NATO is engaging in an elaborate mock nuclear exercise, titled Able Archer, which the East Germans think is the real thing, and a nuclear war is narrowly averted—an event that has a real historical basis.2 The eight episodes begin with Lenora Rauch, the cultural attaché of the East German Permanent Mission in Bonn, and a Stasi agent, watching Ronald Reagan’s now-iconic “Evil Empire” speech on television, in which he warns Americans against the perils of the “so-called nuclear freeze solutions proposed by some,” since that would mean ignoring the “facts of history and the aggressions of an evil empire” (Reagan 1983). Alarmed, Lenora picks up the phone from her luxury apartment to coordinate a plan with Stasi headquarters to gain intelligence on NATO plans. From the outset, then, the narrative focus of the story is on the East German response and resists an overly one-sided understanding of the dominant historical narrative that Reagan’s anti-Communist rhetoric signifies. Lenora’s nephew, Martin Rauch, tagged as a look-alike of a Bundeswehr officer named Moritz Stamm, succumbs to the pressure to take on the role of HVA agent and live in the West, leaving his fiancée and sick mother behind. Lenora ultimately blackmails Martin, promising that if he agrees, his mother (Lenora’s sister) will receive a kidney transplant and the medications from the West that she needs. Lenora and Stasi general Schweppenstette drug Martin and transport him to the home of Tobias Tischbier (Alexander Beyer), a professor and a deep-cover HVA agent in Bonn, where he must prepare for his mission. Lenora, in this portrayal, embodies the cold manipulation and cunning of the Stasi and holds the aims of the state above the health of her sister. The juxtaposition of Lenora’s position with Reagan’s anti-Communist stance underlines how the administrations of the two regimes are fundamentally different, yet the viewer already senses how similar their means of operating can be. Early on Moscow clashes with East Berlin, and West Berlin clashes with Washington, as the military and intelligence agencies respond to Reagan’s policy direction. Throughout the series misunderstandings arise over the plans for “Able Archer” that Martin has covertly photographed. Although “Able Archer” is a NATO simulation of a conflict that escalates to a DEFCON 1 nuclear attack, the Stasi reads the classified document as a threat of an actual attack. As events unfold in the eight episodes, and pressure from Lenora continues, Martin becomes more and more implicated in the misdeeds of the HVA. The son of General Edel, Alex, also in the Bundeswehr but increasingly on the side of the antinuclear protest group headed by Tischbier as part of his cover, kidnaps General Jackson. In covering up for Alex, Martin becomes implicated in the death of the woman Jackson was with and another Stasi agent. Several of Martin’s assigned tasks culminate in a death, and he begins to dissociate his identities: he can be Moritz Stamm, have a relationship with Edel’s wayward daughter, Yvonne, and grow closer to Edel, while also feeling loyal to his fiancée, who becomes pregnant and wants him to come home (although she strongly supports his duty). The double identity of Martin Rauch and Moritz Stamm serves to underline the compromised integrity on both sides of the border, and as in Bridge of Spies, the audience immediately perceives the ambiguity and develops an empathic connection with the spy.

Pluri-medial Networking

In her work on how films contribute to cultural memory, Astrid Erll has pointed to contextual information flows as an essential component. She explains that “intra- and inter-medial strategies are responsible for marking them out as media of cultural memory,” but that these strategies must be actualized through reception of all kinds: “Advertisements, comments, discussions, and controversies constitute the collective contexts which channel a movie’s reception and potentially turn it into a medium of cultural memory. Moreover, all these expressions are circulated by means of media. Therefore we call these contexts ‘pluri-medial networks’” (2008, 396). The effect of pluri-medial networking that Erll describes here determines not only the film’s influence on cultural memory but also its impact on perceptions of current issues. After all cultural memory involves a reconstruction that relates knowledge of the past to present circumstances and understanding, as Jan Assmann notes (Assmann and Czaplicka 1995, 130). The filmmakers take pains to exert control over the pluri-medial networking to mobilize their films to the extent possible. For each of these three films, the directors endeavor to establish a biographical connection to their subject matter through related personal memories and experiences in the United States or Germany and thereby claim an authenticity of the story as a vehicle of cultural memory. Reviewers readily draw comparisons to other spy stories, and interviewers are eager to relate the stories to the news of the day.

Deutschland 83 received prerelease promotion as the first German-language television drama series to be screened on a U.S. network, Sundance TV, with subtitles for the American audience (Roxborough 2015). It was developed by RTL Germany and screened there in the same season. Reviewers in the English-speaking media compared it to the popular series The Americans, about a Soviet KGB couple under deep cover in the United States, leading an American family lifestyle with two children, also set in the early 1980s (Littleton 2015; Brennan 2015; Tate 2016). Both of these series are unusual in that the audience’s sympathies lie squarely with the “enemy”; the narrative focalization leads American and Western European viewers to root for the Communist protagonists, while showing that agents on all sides engage in morally dubious activities to maintain their positions. The two series engage similarly with the current political climate: The New Republic says of The Americans, “It takes the concrete landscape of 1980s America and pumps it full of the retrospective anxiety of our current political age” (Bennett 2013). The networking connections in the reception of the two series serve to show a pattern that links the Cold War to current anxieties about surveillance and build audience engagement.

While viewers share the knowledge of surveillance concerns of the present transnationally, memories of the Cold War are localized, and creators’ claims to historical and biographical authenticity contribute significantly to the pluri-medial networking of these tales of cultural memory. The DVD release of Deutschland 83 includes a fifteen-minute interview with Anna and Jörg Winger, the co-creators of the series (Winger and Winger 2015, DVD, “Deutschland 83: The Creators,” disc 3). Anna Winger is the head writer, and Jörg the executive producer. In speaking about their motivation for creating the series, they emphasized that the series is fictional and entertainment but made authenticity claims by relating an anecdote about the story’s inception. They repeated one particular anecdote in a number of interviews to promote the film. Jörg Winger, during his time in the Bundeswehr in the 1980s, was a radio signaler listening in on communications of Russian troops stationed in the GDR, with the use of a wall of recording reels. The signaler would press record upon hearing key words. When around Christmas the troops in question greeted the West German signalers individually by name, the Bundeswehr knew they had a mole among them. Anna Winger said the appeal was that “everyone was listening. It’s so bizarre to think that they knew everything all along, on both sides.” She went on to observe, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. . . . There are parallels, and when you’re writing about history, you’re always kind of writing about the time you’re living in. We were inspired in large part by the debate about metadata and the NSA, which has been a huge political issue in Germany because of the Stasi history. And that was something we wanted to explore: the idea of being listened to, the question of privacy” (“Deutschland 83: The Creators”).

Through pluri-medial networking, then, they expressed a form of insider knowledge of the current surveillance issues through personal Cold War experiences. Jörg Winger interjected in the interview that “the Stasi was really good at collecting data, and they had so much data that they didn’t know what to make of it. If the Stasi had Google back in those days, they would have been able to make sense of all the data” (“Deutschland 83: The Creators”). The series features comical instances of the race for technology that accompanies the arms race, such as in episode 3, “Atlantic,” in which the East Germans are foiled by the ill-gained 3.5-inch floppy disk, when their state-of-the-art Robotron A 5120 can only read the 8-inch kind. To elaborate on the connection between the personal memory of the data collected by listening and physical gathering and the mass collection and analysis of today: the surveillance data can change, become meaningless, or even impenetrable over time. Jörg Winger’s firsthand knowledge of the technology, then, helped to bridge the gap between past and present in the promotion of Deutschland 83.

In the promotional materials and interviews for Bridge of Spies, a strategy to build audience engagement emerges similarly. In interviews Spielberg highlighted his personal memories and the biographical connection to the story through his father, despite the fact that the script originated with Matt Charman—and linked his own past Cold War anxieties to the current politics of surveillance. Charman, who stumbled across James Donovan’s story in a footnote in a Kennedy biography, wrote the script and pitched it to DreamWorks. Because of Spielberg’s interest in the Cold War, the studio approached him and then brought the Coen brothers on board to further develop the script. At the press conference for the New York Film Festival screening on October 4, 2015, the director expressed concern about cyber-surveillance and noted the topical nature of the surveillance theme: “The cold war was polite in terms of the way we were spying on each other. The way it is today, you just don’t know that when you’re watching television, is television actually watching you? There are just so many eyes on all of us” (quoted in Smith 2015). There is a nostalgia in this comment, exposed by Cold War history not found on the silver screen—the Cold War was not really polite at all. The filmmakers capitalize on gestures of nostalgia in the film through the use of cinematography reminiscent of internationally familiar Hollywood film noir titles, as well as through costuming and spy film genre tropes. On the DreamWorks website for the film, the commentary begins with Spielberg’s biographical connection to the Cold War: his father, Arnold Spielberg, was an engineer who had been part of a General Electric delegation to visit Russia during the year after Gary Powers was shot down, and he had stood in line to see the remains of the U-2 and the flight suit. Their group was asked for their passports and pulled to the front of the line to make a spectacle of them: “This Russian pointed to the U-2 and then pointed to my dad and his friends and said, ‘Look what your country is doing to us,’ which he repeated angrily several times before handing back their passports” (“Bridge of Spies—Production Notes” 2015). Another anecdote, told to the Wall Street Journal, reports Spielberg’s fears about surveillance during the Cold War: His father, a second-generation Jewish immigrant to the United States from Ukraine, who spoke Yiddish and Russian, would speak to people in the Soviet Union over ham radio in the backyard shed, and his son (Steven) would ask him, “What if the FBI finds out you were talking to people in Russia over the radio?” (quoted in Calia 2015). Relating Bridge of Spies to current politics in the same interview, he said, “A frost has settled between today’s Russia and the United States, and it’s the kind of frost that I’m very familiar with, having grown up with the permafrost of the Cold War” (Calia 2015). Like the Wingers, then, Spielberg employed the personal and biographical perspective to claim authenticity and convey local specificity for a collective memory.

In the interviews Spielberg connected his distrust of government players with a preoccupation with ever-growing surveillance, and this distrust emerges within his characters, too. Daniel Clarkson Fisher has identified Spielberg’s wariness of excessive government power as a motif in his films, in which authority figures often tip to overreaching their license, either legal or ethical, and violate citizens’ privacy and civil liberties in a patronizing, corrupt, and often inept manner. This distrust is expressed even in the Indiana Jones movies, which he claims to have modeled on B-movies about flying saucers and Martian invaders in the 1950s, phenomena that were “really about government paranoia, cold war fears, and things like that” (quoted in Clarkson Fisher 2017). For Bridge of Spies, Spielberg rejected a one-sided story and the facile earmarking of a villain: “One of the things I loved about the story was that everyone you think should be wearing a black hat isn’t necessarily wearing that hat, nor did they intend to. It doesn’t make it easy to root for someone who is a spy against the national security of our nation. . . . How could we possibly come out on the other end of this experience caring about this person in the least? But in this case we do, and that was something that made me want to get involved with the project” (“Bridge of Spies—Production Notes” 2015). The political ambiguity in the narrative is therefore at the crux of the project for him and aligns with the contemporary audience member who cares less about the allegiances of those conducting the surveillance now than the fact that surveillance is occurring.

Just as for Deutschland 83 and Bridge of Spies, the biographical connection is a consistent subject of attention in the publicity about Westen. The novel by Julia Franck on which it is based, Lagerfeuer, is a semiautobiographical tale of a mother who leaves East Berlin and must stay for months in the West Berlin transit camp, an aspect always discussed in interviews with the author. Heide and Christian Schwochow rewrote the multiperspectival novel for the screenplay, reducing the story’s narrative core to Nelly and Alexei, whose adapted fictional stories incorporate details from the screenplay writers’ lives. The Schwochows applied to leave the GDR in the 1980s, and the question of leaving or staying had always been an issue. Their exit visa was granted on November 9, 1989, the day the border opened (Brady 2015). The sequences depicting alienating incidents for Alexei in the West Berlin school originate in some cases directly from Christian Schwochow’s experiences in his new school in Hannover after his family left Berlin. Although the Schwochows may well have had interactions with the Stasi, since Christian’s father, Rainer Schwochow, unsuccessfully attempted to escape the GDR in 1970 and subsequently spent a year and a half in prison (Brady 2015), the reception and marketing of this film employed the biographical not primarily to address the surveillance practices of West and East Germany. The interviews and press kit shifted instead to the foregrounded subject of the migration experience, being caught in the in-between, and the harm brought about by the oversimplified duality of the presumed better and worse Germany. Die Zeit’s Oliver Kaever describes the film as “something between a refugee drama and a suspenseful spy thriller” and praises Schwochow for the “ambivalent discursive space” he created, as the protagonist is caught “between worlds” (2015). The refugee crisis in Europe, precipitated by the refugees flowing out of war-torn Syria, Somalia, and Afghanistan and dying by the hundreds in the Mediterranean in their attempts to reach Europe, was just beginning to intensify in 2014 when Westen had its theatrical release. The film was released to theaters in the United States in November 2014 and it began to have screenings at many Goethe Institutes worldwide around the twenty-fifth anniversary of German unification, leading Schwochow to make the connection between the current refugee crisis and the experience depicted in the film more overt in his interviews. In an interview with IndieWire, he spoke of his research preparation, which included visiting a refugee center in Berlin for people from Syria and Iraq and getting a sense of their physical and psychological experiences (Aguilar 2014). At the time of the German theatrical release, Schwochow connected the subject matter to the Snowden discussion and the growing awareness of the surveillance of citizens in the West: “We have known at least since Edward Snowden the kind of role that the Western secret services play. My film aims to show, then, that even a Western democracy has very particular mechanisms that, in the first instance, have nothing at all to do with freedom” (Kessler 2014). He repeated the same line before the American premieres and challenged the rhetoric of freedom (Teich 2014; Aguilar 2014). For him the tendency to portray the superior freedom of the West, at the cost of overlooking similar surveillance mechanisms in the West, demanded a corrective.

Cinematography of Blurring

Having established that the narratives and audience development strategies for these thrillers associate personal and collective memories of the Cold War with a critique of present-day surveillance, let us turn to the aesthetic devices employed to this end. As already indicated, the cinematography contributes substantially to the expression of the anxiety that the controlling surveillant eye engenders. When one considers that the video surveillance practices that are now widespread have developed in tandem with the medium of cinema itself, it is fitting that filmmakers use images to investigate how surveillance can blur truth and reality, as well as shed light on it, and how meaning can shift with camera angle and the surveillant perspective. Thomas Levin points out that the pioneering 1895 film by the Lumière brothers, Workers Leaving the Factory, could be considered a form of surveillance of the workers (2002, 581). Catherine Zimmer also gives numerous examples of how early cinema produced stories of cameras catching crimes in progress, thereby producing social commentary at the same time as a form of disciplinary enforcement of norms (2015). Films can call the function of the image into question, and filmmakers have historically investigated the capacity of the image to deceive, mask, or blur. The cinematographic technique of blurring dates back to cinema’s beginnings, and many have connected blurred or fast-moving images to the anxiety and paranoia of modern life. In 1903 Georg Simmel wrote in “The Metropolis and Mental Life”:

The psychological basis of the metropolitan type of individuality consists in the intensification of nervous stimulation which results from the swift and uninterrupted change of outer and inner stimuli. Man is a differentiating creature. His mind is stimulated by the difference between a momentary impression and the one which preceded it. Lasting impressions, impressions which differ only slightly from one another, impressions which take a regular and habitual course and show regular and habitual contrasts—all these use up, so to speak, less consciousness than does the rapid crowding of changing images, the sharp discontinuity in the grasp of a single glance, and the unexpectedness of onrushing impressions. These are the psychological conditions which the metropolis creates. With each crossing of the street, with the tempo and multiplicity of economic, occupational and social life, the city sets up a deep contrast with small town and rural life with reference to the sensory foundations of psychic life. (1950, 410)

With reference to the innovative 1927 film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, Ágnes Pethő describes the sequences of images of the metropolis, pulsating and flowing with the rhythm of the music, as a representation of the “liquid city” (2011, 103). “Such a musical (video-clip like) rendering of the flow of the traffic and the clustering of (illuminated) skyscrapers has,” she points out, “already become one of the running clichés of television series” like CSI or Law and Order (103). There is a connection of the urban environment to the anxiety and paranoia of modernity, as expressed through the rapidly moving images, blurring, and lack of separation. Joachim Paech, in turn, establishes that blurred, defocused, or vague (unscharfe) images are always dependent on “norms of correct seeing” and are therefore relational (2008, 345). He considers especially the intermedial aspects of blurring, such as painted films or paintings in films, and talks about the dissolution of demarcation lines between art forms. The relational reception of the images involves “psychophysical code” that filmmakers instrumentalize. Kathrin Rothemund, in her study of how filmmakers use surveillance footage in several feature films, articulates that the blurred footage expresses “images in crisis” as well as “images of crisis” (2016, 1). The focused and blurred images “constantly negotiate the interrelation between fact and fiction, between subjectivity and objectivity, between dream and reality, between time and place. Images between vagueness and acuity should be dealt with according to their visual, temporal or movement density, the superimposition of perceptive attention and the creativity of interpretive approaches” (1). She goes on to point out that this is an issue of technology as well as aesthetics. In cinema, there are numerous tools and strategies that can bring about blurring or vagueness, which include the technologies of the camera and material—she lists lenses, depth of focus or depth of field, soft focus and diffusion, focus shift, the graininess of film material (16 mm/8 mm), various filters, double exposure—and can extend to weather and atmosphere or physical barriers in the mise-en-scène that obscure or partially block the view of the narrative subject.

The three productions addressed in this chapter make extensive use of all these forms of defocus and blur, instrumentalizing them for “connotative surplus value,” as Paech terms it (2008, 359). In surveillance films blurred footage can signify authenticity because lower-quality footage that could come from constantly looping security tapes or nonprofessional camera work signals a kind of mechanical objectivity. These various forms of blurring have become pronounced in many recent works, especially in the films that deal directly with surveillance politics, such as Oliver Stone’s Snowden (2016), to cite a prominent example. In the films addressed here, a dominant use of the blurring is to convey political ambiguity, both in a shifting understanding of historical developments and with respect to the climate of surveillance now: who is watching and why, and how do we judge the practices and the recordings?

Certainly, in Deutschland 83 the camera movements, blurring, and framing are key devices in the creation of political and moral ambiguity. Constantly presented in duplicate in mirrors, windows, and doorways and peered at in grainy surveillance footage, the undercover Stasi agent Martin Rauch confronts daily the fragility of his ideological position. He does what the Stasi asks him to do but finds himself developing close relationships with the West German targets, and he often unwittingly uncovers the weaknesses and morally questionable acts of high high-ranking players on both sides—for example, he accidentally shuttles explosives from the East to Carlos the Jackal, resulting in mass casualties, to his great dismay, and sympathizes with General Edel, who worries about his renegade son. The television series draws on Mad Men–style nostalgia aesthetics and shifts between the use of familiar tropes and the deconstruction of political and moral binaries. In the first episode, “Quantum,” the fast pace and blurring techniques employed by cinematographer Philipp Haberlandt bombard the senses with the disorientation of the protagonist, the split identities of West and East Germany in 1983, the agitation, tension, and jangled nerves of the nuclear arms race. The blurring reveals how covert observation is happening on both sides, and the visual representation of surveillance conveys the inner inquietude that it causes. The images of doubling begin before the opening credits, with Martin’s mother and his aunt, Lenora, embracing at the same time as Martin and his girlfriend Annett, and Lenora peering through the window-like kitchen pass-through at Martin. When Stasi general Schweppenstette arrives to recruit Martin, the viewer position is on the other side of a wrought-iron divider in the living room, and we observe Martin’s reaction to recruitment through a grid, with his face half in shadow and framed by the backs of the heads of Lenora Rauch and Schweppenstette. The position of the camera obscures the view, and the bifurcation of both the scene and the protagonist’s face suggest shady, or unclear, motives and decisions (fig. 10.1).

The scene cuts to a slow zoom on his mother and Lenora in the kitchen, through a bead curtain—another form of obstruction—in the doorway. Martin’s last words are “I won’t do it,” before he blacks out from the sedative in the tea and wakes up in Bonn. Looking through the window, he sees a dreamlike, blurred, and distorted view of Bonn. This compelling sequence is replete with blurring: Martin passes through a doorway, soon to emerge as Moritz Stamm, and a reflection appears as a haunting, ghostly apparition, as the beveled glass of the door further fractures the clarity of Martin’s image (see fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.1. Martin’s recruitment viewed through wrought-iron room divider (Deutschland 83).

His identity is divided before our eyes. He then stands in a second doorway, framed by beveled-glass doors and a beveled-glass half-circle window over his head, his small figure slightly out of focus, as he asks the question, “Where am I?” As Lenora Rauch and Tobias Tischbier, in sharp focus, tell him his assignment, he becomes angry, and the background blurs as the camera draws his face into shallow focus. After Martin has reluctantly changed into his Western brand-name Puma T-shirt, jeans, and Adidas shoes, Lenora views with satisfaction from a shadowy doorway across from him, his face, in turn, halved by the shadow in the opposite doorway. He turns to sprint down the spiral staircase, through the seemingly endless doorways and gates of the house and property, where the cinematographer employs blurring of rapid movement, accompanied by a racing soundtrack, to express psychological disorientation, as in Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. He pauses briefly at an electronics store where Bundesrat president Franz Josef Strauß speaks from multiple televisions about the million deutsche mark loan provided to the GDR (fig. 10.3), preceding his meeting with General Secretary Erich Honecker—a use of archival footage to layer the questions of representation of reality and of political position as they shift over time.

Fig. 10.2. Martin refracted (Deutschland 83).

The camera points from the inside of the store to the corner of the display window, such that we see three televisions, a reflection of a television in the windowpane and, projected onto Martin’s Puma T-shirt, a close-up image of Strauß, followed by an image of Erich Honecker on the television screen as he shakes hands with Strauß. The sensory overload of Western culture is visually and physically impressed on his body, and his understanding of the environment is blurred. The multiple screens echo the multiplicity of perspective, just as the camera angles in the sequence emphasize that he is being watched. The historical reference made by the archival television footage reveals the public face of détente and diplomacy, which serves to hide from view the espionage activities, driven by fundamental distrust. The CSU chair Strauß, an avowed anti-Communist who had lost in his bid for the chancellorship in the 1980 election, negotiated a billion deutsche mark loan to prop up the failing East German economy. His big business friend Josef März brought him in contact with his negotiating partner, Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, East German international trade minister and a Stasi colonel. Strauß, whose tactics and approach found disfavor among many, including in his own party, answered in these negotiations only to the new chancellor, Helmut Kohl, keeping his other government colleagues in the dark. He claimed credit for a GDR humanitarian concession, the removal of the automatic firing devices at the so-called death strip, which turned out later to be a ruse: Honecker had announced plans to dismantle these already a year earlier, but Strauß did not know this (Wiegrefe 2017). The cinematography of this sequence serves to externalize the layers of secrecy, calculation, and espionage that lie beneath these television images and Martin Rauch’s initiation into this world.

Fig. 10.3. Martin on the run in the capitalist West (Deutschland 83).

A frantic Martin runs on, into the supermarket, where hyper-real colorful shelves of goods frame him, as he stops in his tracks, overwhelmed by Western consumer culture. Indeed, material culture is a thematic core issue for surveillance that speaks to the contemporary viewer: it is the global online consumer and social media activity that generates the most personal information about individuals and in turn influences behavior.

In Westen the cinematographer uses the hand-held camera and its position to emphasize the surveillant gaze: unsteady footage, suboptimal views partially obscured by trees or buildings, with subjects sometimes out of focus, reveal the human observer behind the lens. The film opens with a view from across the street: a poorly exposed view of a gray apartment block partially obscured by blowing snow, with two small figures in the window. We are briefly introduced to Nelly, Alexei, and Alexei’s father, Vassily, bidding a tender farewell before Vassily leaves. The same across-the-street point-of-view shot recurs in quick succession, with the title “three years later,” this time without Vassily. The frontal view cuts to an obscured shot in which the surveillant camera is concealed behind the foliage in the foreground. Immediately upon crossing the border, the camera draws attention to itself once again, as it captures the sun’s glare on the lens in Nelly’s moment of relief (fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.4. Nelly across the border (West).

Although she is unaware that someone is watching her here, too, the viewer is already on guard. The covert observation from afar is present at every moment, before, during, and after her stay at the transit camp.

In figure 10.5 the window frame and the view over the shoulder of the CIA agent emphasize the constant framing by the surveillant gaze—by the human eye or the eye of the camera. When Nelly has finally passed through the threshold of interrogation and is free to come and go as she pleases, she celebrates with her son in the park, and the position of the camera signals surveillance yet again, from behind a tree at a distance, then zooming in to a yellow blur as the camera suggests that someone is monitoring mother and son in an intimate moment of playful wrestling in the leaves. Nelly is all too aware that someone may be watching her at any time and the degree to which information is concealed from her. While in Deutschland 83, Martin appears as a double or a ghost of himself (fig. 10.2), Nelly is haunted by visions of her lover, Vassily, who may be living or dead (fig. 10.6). The partial obstruction by the window, the unfocused shot, the reflection, and the position of the eyes—Nelly’s gaze from behind and the camera’s (surveillant) gaze from the fore—contribute to the anxiety and uncertainty of her position.

Fig. 10.5. John Bird watches Nelly from a window (West).

Like Vassily, Hans, a fellow resident of the transit camp, has a haunting presence. He has been there for a long time, befriends her son, and tries to befriend her. After a warning from another camp resident to watch out for the Stasi, who are everywhere, it is clear that she suspects that Hans may have connections to the Stasi, and she tries to keep her son from him. He seems to appear randomly and too coincidentally when she is in distress. By the film’s conclusion, he has been redeemed in her eyes after he explains his dissident past and has helped her and her son; he is at the door to join them for Christmas dinner in the final scene observed from a surveillant position outside the building. Nelly appears to accept the level of uncertainty and ambiguity that she has been dealt. After Hans points it out, she sees that her escalating paranoia, signaled by increasing camera movement, backward glances, and close-ups of her distressed face, is hurting herself and her son. In subsequent scenes the camera movement slows, Nelly smiles calmly, and she unhesitatingly answers the apartment buzzer to welcome Hans.

In Bridge of Spies, the cinematographer uses less camera blurring to work with the theme of political ambiguity, although this is certainly present in many of the stylized noir scenes, such as when someone is trailing Donovan on a dark and rainy night (fig. 10.7), or when the blurred stream of subway passengers in trench coats and fedoras allows Abel to evade the agents in pursuit.

Fig. 10.6. Nelly sees a ghost (West).

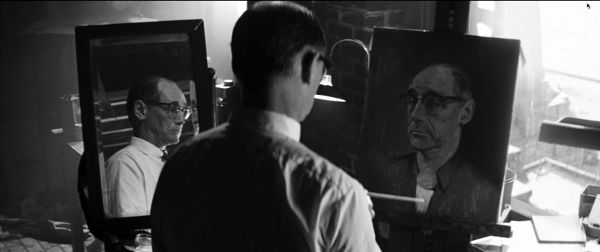

In the rain sequence, shown in figure 10.7, Donovan is out of focus in the foreground, while the rain and dark obscure the features of the trailing agent, adding tension and anxiety to the scene. Since the camera dwells on this scene to build suspense, and the identity of the figure is revealed minutes later as an American—an FBI agent—the sequence undermines the notion of the hostile foreign surveillant. Bridge of Spies, however, more heavily employs the technique of doubling, or even tripling, images, extending the model even to the narrative structure. In figure 10.8, in the film’s opening sequence that introduces us to Abel and begins to provide character development, the camera shows him from behind in triplicate (painting, person, and mirror reflection) in a noir-style image of fragmented identity and an illustration of Paech’s intermedial blurring.

The shot draws the audience affectively to the face, and together with the title of the film, it prompts us to begin to speculate about the multiple identities of the character—one with whom we immediately begin to empathize. How does he see himself, and how do others see him, in the mirror and on the canvas? Which one, if any of them, is “real”? In the fade-in transition shown in figure 10.9, the blurred image of Abel appears as an uncanny—even ghostly—double with Powers and strongly suggests an equivalence of their positions. The repeated pairing of images underlines the narrative question of why the American U-2 surveillance pilot should represent a superior ethical or national position to that of the Soviet agent.

Fig. 10.7. Donovan trailed by FBI agent (Bridge of Spies).

Political Ambiguity on Screen

The three productions described here, Westen, Deutschland 83, and Bridge of Spies, share the dual objectives of cultural memory and a close examination of the current seen and unseen risks of mass surveillance. Their approach to the memory of the Cold War marks a shift from previous narratives in that they emphasize political ambiguity: the individual characters become enmeshed with the questionable deeds and collective fears of whole regimes. The characters in these stories have no alternative but to live with the intrusive cameras and eyes that watch them, but the films challenge the audience to consider their willing participation in the omnipresence of surveillance. The transnational filmmaking and marketing address the fact that there are Cold War transatlantic stories, located at the Berlin nexus of East and West, that are as relevant to us today as ever, but which take on new meaning in a globalized environment in which nation states have arguably yielded much power over social and political spheres to corporations. Online sales will draw the spy stories themselves into forms of digital surveillance to sell the DVDs and streaming versions, along with products that will be marketed on these sites, and promotions of other movies by the same directors and actors: “Customers who bought this item also bought.” The film Westen calls on audiences to reexamine the notion of the “better Germany” in the Federal Republic of Germany, to show that ideologically motivated suspicion and fear were not unique to the GDR and aspires to convey the displacement migrants experience in the modern and now the liquid modern era. In terms of funding and marketing, Westen is predominantly German-funded, but with the support of the MEDIA Program of the European Union, and it has targeted the international audience beginning with its Montreal premiere. With its 1980s soundtrack and attractive young cast, Deutschland 83 has a lighter touch and a pop-culture nostalgia that nonetheless aims for a transatlantic reexamination of the Reagan/Brezhnev era, both in its noteworthy binational television funding and release and in its East German perspective. Bridge of Spies, though German input is significant, through the coproduction by Studio Babelsberg and the casting of German actor Sebastian Koch of The Lives of Others fame as the East German negotiator, culminates in an indubitably American ending: the film presents Donovan as the story’s hero and champion of the American justice system. Nonetheless, the narrative, structural, and cinematographic features of the film serve to shift the viewer’s empathic perspective and muddy the waters of Cold War history. Concerns with the penetration of state surveillance into the private sphere and its consequences, then, are a preoccupation of all these screen stories, and they reframe, complicate, and mobilize memory of the Cold War in a context of acknowledged political ambiguity.

Fig. 10.8. Triple image self-portrait of Rudolph Abel (Bridge of Spies).

Fig. 10.9. Faces in parallel: Abel and Powers (Bridge of Spies).

Notes

1. The novel was translated by Anthea Bell after the release of the film, with the title West, published by Vintage in 2015.

2. In 2013 Mark Kramer published research that refutes the notion that the Soviets failed to recognize that Able Archer was an exercise, not the real thing (Kramer 2013, 129–50).

References

Aguilar, Carlos. 2014. “Beyond the Wall: Dir. Christian Schwochow on His Intriguing Historical Drama ‘West.’” IndieWire, November 18. http://www.indiewire.com/2014/11/beyond-the-wall-dir-christian-schwochow-on-his-intriguing-historical-drama-west-171799/.

Assmann, Jan, and John Czaplicka. 1995. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65:125–33.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

—. 2006. Liquid Fear. Cambridge: Polity.

Bauman, Zygmunt, and David Lyon. 2013. Liquid Surveillance: A Conversation. Cambridge: Polity.

Bennett, Laura. 2013. “The Spies Next Door: The Americans Is a Cold War Thriller for Our More Ambiguous Age.” New Republic, January 30. https://newrepublic.com/article/112284/fxs-americans-reviewed.

Brady, Martin. 2015. “West Q+A with Christian Schwochow: 04 June 2015.” BFI YouTube Channel, June 11. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mOyxDf49zGo.

Brennan, Matt. 2015. “‘Deutschland 83,’ ‘The Americans,’ and the End of an Era in TV Drama: A Tale of Two Spy Stories; ‘The Americans’ Has Two Seasons Left, but ‘Deutschland 83’ May Shape TV’s Future.” IndieWire, June 23. http://www.indiewire.com/2015/06/deutschland-83-the-americans-and-the-end-of-an-era-in-tv-drama-trailer-186944/.

“Bridge of Spies—Production Notes.” 2015. DreamWorks Animation LLC, Storyteller Distribution Co. LLC. http://dreamworkspictures.com/films/bridge-of-spies#production_notes.

Calia, Michael. 2015. “Steven Spielberg Remembers the Cold War in ‘Bridge of Spies’; Steven Spielberg recalls the Cold War; Tom Hanks plays a lawyer defending a Russian spy.” Wall Street Journal, October 8. https://www.wsj.com/articles/steven-spielberg-remembers-the-cold-war-in-bridge-of-spies-1444145673.

Charman, Matt, Ethan Coen, and Joel Coen. 2014. Bridge of Spies: Final Shooting Script 12.17.14. DreamWorks. http://dreamworksawards.com/download/BOS_screenplay.pdf.

Clarkson Fisher, Daniel. 2017. “Spielberg and Surveillance.” Video essay, February 17. https://vimeo.com/204631958.

Erll, Astrid. 2008. “Literature, Film and the Mediality of Cultural Memory.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 389–98. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Franck, Julia. 2003. Lagerfeuer. Köln: Dumont.

“Geheimdienste überwachten mehr als 37 Millionen E-Mails.” 2012. Spiegel Online, February 25. http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/schlagwort-fahndung-geheimdienste-ueberwachten-mehr-als-37-millionen-e-mails-a-817499.html.

Kaever, Oliver. 2015. “Warten auf die Freiheit: Christian Schwochow hat Julia Francks Roman ‘Lagerfeuer’ verfilmt; Im Notaufnahmelager muss eine DDR-Bürgerin lange auf ihre Weiterreise in die Freiheit warten.” Die Zeit, March 24. http://www.zeit.de/kultur/film/2014-03/westen-film.

Kelly, Mike. 2017. “Kellyanne Conway Suggests Even Wider Surveillance of Trump Campaign.” USA Today, March 12. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/03/12/kellyanne-conway-surveillance-trump-campaign-wider/99109170/.

Kessler, Tobias. 2014. “Interview mit Christian Schwochow über seinen Film ‘Westen.’” Saarbrücker Zeitung Kinoblog, March 27. http://www.meinsol.de/blog/show.phtml?cbid=36688.

Kramer, Mark. 2013. “Die Nicht-Krise um ‘Able Archer 1983’: Fürchtete die sowjetische Führung tatsächlich einen atomaren Großeingriff im Herbst 1983?” In Wege zur Wiedervereinigung: Die beiden deutschen Staaten in ihren Bündnissen 1970 bis 1990, edited by Oliver Bange and Bernd Lemke, 129–50. Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag.

Levin, Thomas. 2002. “Rhetoric of the Temporal Index: Surveillant Narration and the Cinema of ‘Real Time.’” In CTRL[SPACE]: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother, edited by Thomas Levin, Ursula Frohne, and Peter Weibel, 578–93. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Littleton, Cynthia. 2015. “SundanceTV Deutschland 83 Breaks Cultural Barriers with Cold War Chiller.” Variety, June 17. http://variety.com/2015/tv/news/deutschland-83-sundancetv-german-language-drama-1201522499/.

Lyon, David. 2010. “Liquid Surveillance: The Contribution of Zygmunt Bauman to Surveillance Studies.” International Political Sociology, no. 4, 325–38.

—. 2015. Surveillance after Snowden. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

“Merkels Handy steht seit 2002 auf US-Abhörliste.” 2013. Spiegel Online, October 26. http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/nsa-ueberwachung-merkel-steht-seit-2002-auf-us-abhoerliste-a-930193.html.

Paech, Joachim. 2008. “Le Nouveau Vague oder Unschärfe als intermediale Figur.” In Intermedialität, analog/digital: Theorien, Methoden, Analysen, 345–60. Munich: Fink.

Pethő, Ágnes. 2011. Cinema and Intermediality. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

Poitras, Laura, Marcel Rosenbach, and Holger Stark. 2013. “NSA überwacht 500 Millionen Verbindungen in Deutschland.” Spiegel Online, June 30. http://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/netzpolitik/nsa-ueberwacht-500-millionen-verbindungen-in-deutschland-a-908517.html.

Reagan, Ronald. 1983. “Remarks at the Annual Convention of the National Association of Evangelicals, March 8, 1983.” Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=41023.

Rothemund, Kathrin. 2016. “Traversing Media—Blurring Images: On the Interrelation between Moving Images of Crisis and Blurred Aesthetics.” Paper presented at the Network of European Cinema Studies Conference, Brandenburgisches Zentrum für Medienwissenschaft, Potsdam, July 28–30.

Roxborough, Scott. 2015. “FreemantleMedia International Takes German Series Deutschland 83.” Hollywood Reporter, January 15. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/fremantlemedia-international-takes-german-series-763994.

Schwochow, Christian, dir. 2013. Westen (West). Feature film. Zero One Film.

Simmel, Georg. 1950. “The Metropolis and Mental Life.” In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited and translated by Kurt H. Wolf, 409–24. Glencoe IL: Free Press.

Smith, Nigel M. 2015. “Steven Spielberg: Compared to Today’s Surveillance, the Cold War Was Polite.” Guardian, October 5. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/oct/05/steven-spielberg-tom-hanks-bridge-of-spies-cyber-hacking-torture.

Spielberg, Steven, dir. 2015. Bridge of Spies. Feature film. DreamWorks et al.

Stone, Oliver, dir. 2016. Snowden. Feature film. Endgame Entertainment.

Tate, Gabriel. 2016. “Deutschland 83: ‘A Lot of People Were Happy in East Germany.’” Guardian, January 3. https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/jan/03/channel-4-cold-war-drama-deutschland-83.

Teich, David. 2014. “Interview: Christian Schwochow (Director—‘West’).” Indiewood Hollywouldn’t, November 6. https://indienyc.com/interview-christian-schwochow-director-west/.

Timberg, Craig, Elizabeth Dwoskin, and Ellen Nakashima. 2017. “WikiLeaks: The CIA Is Using Popular TVs, Smartphones and Cars to Spy on Their Owners.” Washington Post, March 7. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2017/03/07/why-the-cia-is-using-your-tvs-smartphones-and-cars-for-spying/?utm_term=.66874f095a4e.

Wiegrefe, Klaus. 2017. “Die Legende vom listigen Franz Josef.” Der Spiegel, January 19. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/ddr-wie-erich-honecker-csu-chef-franz-josef-strauss-austrickste-a-1130208-druck.html.

Winger, Anna, and Jörg Winger, dirs. 2015. Deutschland 83. Television series. RTL. Freemantle Media International, DVD.

Zimmer, Catherine. 2015. Surveillance Cinema. New York: New York University Press.