31 MAN OVERBOARD

The most effective way of dealing with this terrible hazard is to have a positive policy on safety harnesses so as to ensure that it never happens at all. Every crew member should be issued with his own equipment, so that it can be adjusted to size before it is needed. It should then be worn and used as a matter of course at any time when either you, or any of your crew, might feel it necessary. If you are looking for guidance as to when this might be, the following may prove helpful:

If you are wondering whether or not to clip on, do it.

If you are wondering whether or not to clip on, do it.

When you are sailing in open water and conditions are such that you would consider reefing the mainsail, clip on at any time you leave the cockpit.

When you are sailing in open water and conditions are such that you would consider reefing the mainsail, clip on at any time you leave the cockpit.

In gale or near-gale conditions when a knock-down seems even a remote possibility, everyone on deck or in the cockpit should be clipped on.

In gale or near-gale conditions when a knock-down seems even a remote possibility, everyone on deck or in the cockpit should be clipped on.

Clip on when approaching an area of tidal disturbance. It may be worse than you expect.

Clip on when approaching an area of tidal disturbance. It may be worse than you expect.

Even in fair weather, clip on at night.

Even in fair weather, clip on at night.

If, having taken all these precautions, you do lose someone, man-overboard recovery is a two-stage operation. The first part is to bring the boat close to the casualty and keep her there for long enough to be able successfully to execute the second, which is assisting him back on board.

Whatever is happening, the most vital aspect of phase one is never to lose eye contact with the casualty. As soon as he goes over, throw lifebuoy and danbuoy after him, then designate someone to watch him continuously even if he is carrying a radio homing device. Even a few seconds’ slackness can result in your crew member being lost to view among the waves, quite possibly for ever. On a short-handed cruiser, this requirement can be a tall order, but nonetheless it must be followed. If you are left alone on board, you will have to do your best, but always remember the danger of losing touch.

There are two basic systems for bringing a boat to rest close by, or even alongside, a crew member in the water. Which you choose will depend on your yacht’s characteristics, the sea conditions, and how you rate your own competence.

THE REACH-TURN-REACH

THE REACH-TURN-REACH

This method works well in a moderate-sized, manoeuvrable yacht with an expert in command. It is successful in any conditions and has the benefit of not requiring any recourse to the engine. Here is how it goes, step by step (see also Fig 31.1):

Immediately sail the boat away, properly trimmed, on a true beam reach. Now you should hit the MOB button on your GPS and mark the time, if appropriate.

Immediately sail the boat away, properly trimmed, on a true beam reach. Now you should hit the MOB button on your GPS and mark the time, if appropriate.

As soon as you have enough room to manoeuvre (how much this is depends on many factors; only practice can give you the necessary expertise), either tack or gybe. Bear in mind that tacking will take you further upwind. Gybing will lose you ground. Either may be what you require.

As soon as you have enough room to manoeuvre (how much this is depends on many factors; only practice can give you the necessary expertise), either tack or gybe. Bear in mind that tacking will take you further upwind. Gybing will lose you ground. Either may be what you require.

You want to approach the casualty on a close-reach, because no other point of sailing gives you such control over the boat’s speed. So steer directly for him, release your sheets to see if all sails will spill wind on demand, and determine whether or not her attitude to the wind is to your satisfaction.

You want to approach the casualty on a close-reach, because no other point of sailing gives you such control over the boat’s speed. So steer directly for him, release your sheets to see if all sails will spill wind on demand, and determine whether or not her attitude to the wind is to your satisfaction.

If she is on a close-reach, lose way just as if you were picking up a mooring with no tide running (as in Chapter 5).

If she is on a close-reach, lose way just as if you were picking up a mooring with no tide running (as in Chapter 5).

If she’s ‘below’ a reach (i.e. to leeward of the desired heading, or too hard on the wind), make all the ground you can closehauled, ‘above’ the target, before bearing away and spilling wind on your final close-reaching approach. Fail to do this, and the boat will stall into the windward sector as soon as you try to slow down.

If she’s ‘below’ a reach (i.e. to leeward of the desired heading, or too hard on the wind), make all the ground you can closehauled, ‘above’ the target, before bearing away and spilling wind on your final close-reaching approach. Fail to do this, and the boat will stall into the windward sector as soon as you try to slow down.

If she’s ‘above’ the desired heading (you’ll see this immediately because the mainsail will refuse to spill wind), bear away sharply, run downwind for a few yards, then shape up for the casualty once more, reassessing your angle to the wind.

If she’s ‘above’ the desired heading (you’ll see this immediately because the mainsail will refuse to spill wind), bear away sharply, run downwind for a few yards, then shape up for the casualty once more, reassessing your angle to the wind.

You sailed away from the casualty initially in order to gain the searoom to execute either of these last two manoeuvres, should they be required. Do not waste that ground through indecision.

You sailed away from the casualty initially in order to gain the searoom to execute either of these last two manoeuvres, should they be required. Do not waste that ground through indecision.

In moderate conditions, you’ll discover that if you stop to wind ward of the man with the breeze well out on your weather bow, the stalling boat will slide down towards him, particularly if you put the helm hard ‘down’ to luff off the last of her way. You will now be able to pick up amidships. Watch out for flogging jib sheets and if you’ve a roller genoa, furl it before you go out on the deck.

In moderate conditions, you’ll discover that if you stop to wind ward of the man with the breeze well out on your weather bow, the stalling boat will slide down towards him, particularly if you put the helm hard ‘down’ to luff off the last of her way. You will now be able to pick up amidships. Watch out for flogging jib sheets and if you’ve a roller genoa, furl it before you go out on the deck.

In hard weather, you may prefer to stop a few yards away from the casualty and heave him a line so as to avoid any possibility of running him down. When it’s really blowing, there is a respectable school of thought that says you should stop to leeward of the man so as not to be driven down on to him.

In hard weather, you may prefer to stop a few yards away from the casualty and heave him a line so as to avoid any possibility of running him down. When it’s really blowing, there is a respectable school of thought that says you should stop to leeward of the man so as not to be driven down on to him.

Fig 31.1 Man overboard: reach-tack-reach pick up (note the close-reaching approach).

Fig 31.1 Man overboard: reach-tack-reach pick up (note the close-reaching approach).

Finding that close-reach in the heat of the moment requires judgement of a moderately high order. Don’t be disheartened if it seems hard going when you begin to practise, and always remember that in a genuine crisis there is nothing to stop you having your engine turning over – check round for ropes over the side first! – to give the boat a last shove up to windward if need be. Try the manoeuvre again every so often and see if you are improving, but stick to the ‘crash-stop’ method described below if you are in the slightest doubt.

Reach-turn-reach is said by some to be the best way of coming back to a casualty in the water, but it has two drawbacks. To be sure of pulling it off, boat handling of a high standard is required, and it involves taking the boat away from the casualty while working up the searoom for the pick-up approach. At night, you may well be uncertain that the victim has caught hold of the flashing light you threw him; the light may even have failed to function – such occurrences are all too common – so you may feel that the risk of losing touch with him in the dark is too great. Even so, it is well worth taking the time to practise the method, especially if your engine is unreliable, non-existent, or lacks the power to deliver the punch needed in heavy seas.

CRASH STOP

CRASH STOP

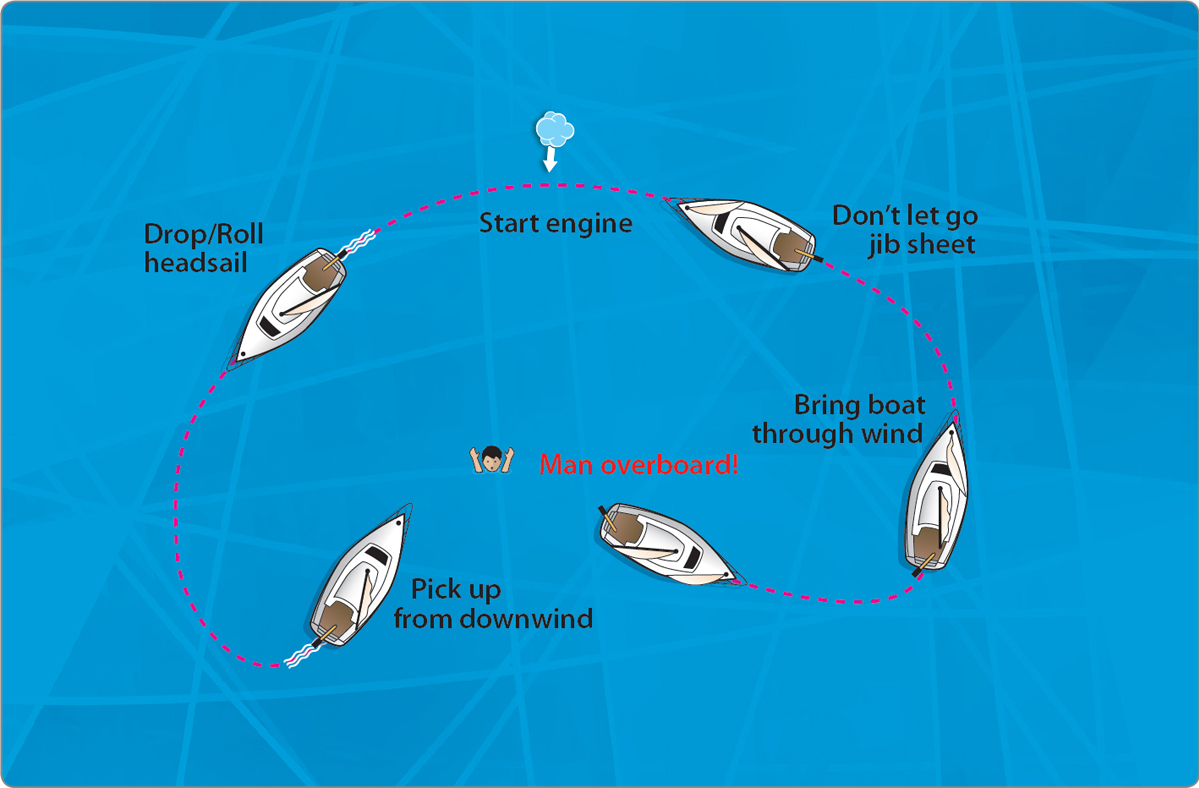

The crash stop method offers the huge benefit of keeping boat and man over board close together throughout the affair (Fig 31.2). This is what you do:

Fig 31.2 Man overboard: crash stop.

Fig 31.2 Man overboard: crash stop.

As soon as your man goes over the side, push the helm hard down, regardless of your point of sailing. This will normally tack the boat.

As soon as your man goes over the side, push the helm hard down, regardless of your point of sailing. This will normally tack the boat.

Leave your headsail sheets made fast so that the jib and/or staysail come aback.

Leave your headsail sheets made fast so that the jib and/or staysail come aback.

The yacht is now effectively hove to. The reality in a seaway is that this is often a messy manoeuvre, with ropes and sails flailing around in disarray, but in spite of this discomfort, the boat will often settle down close enough to the casualty to pass him a line. If this isn’t the case, it may well be worth trying to work the boat across to him by juggling sheets and tiller.

The yacht is now effectively hove to. The reality in a seaway is that this is often a messy manoeuvre, with ropes and sails flailing around in disarray, but in spite of this discomfort, the boat will often settle down close enough to the casualty to pass him a line. If this isn’t the case, it may well be worth trying to work the boat across to him by juggling sheets and tiller.

If it looks as though you will not come close enough to effect a rescue, you will have to motor-sail. This is where the modern yacht with her powerful, reliable auxiliary scores over her predecessors, but first, you have a job to do. Unless you have a spare person to detail for the duty, nip below, press the MOB button on your GPS – assuming it is running – and note the time. Now carry on with the main task.

If it looks as though you will not come close enough to effect a rescue, you will have to motor-sail. This is where the modern yacht with her powerful, reliable auxiliary scores over her predecessors, but first, you have a job to do. Unless you have a spare person to detail for the duty, nip below, press the MOB button on your GPS – assuming it is running – and note the time. Now carry on with the main task.

Motor-sailing from the hove-to mode is the favourite means if you entertain secret doubts about your capacity to make the grade as a boat handler. It is also the best way to teach your crew to cope in the event of the real catastrophe of falling overboard yourself.

Motor-sailing from the hove-to mode is the favourite means if you entertain secret doubts about your capacity to make the grade as a boat handler. It is also the best way to teach your crew to cope in the event of the real catastrophe of falling overboard yourself.

Keeping a constant eye on the victim, drop your headsail or roll it away. Now work the boat to a point downwind of the casualty and start the engine after double-checking, then checking again, that no rope of any description can find its way into the propeller. The pick-up is made with the boat approaching from slightly off dead downwind with the mainsheet pinned amidships. The sail steadies the boat while the propeller maintains control, but it is important to keep the person in the water towards the ‘shoulder’ of the boat. A propeller can inflict traumatic injuries on a swimmer, which, in his already shocked state, could render the object of the whole exercise somewhat futile.

Keeping a constant eye on the victim, drop your headsail or roll it away. Now work the boat to a point downwind of the casualty and start the engine after double-checking, then checking again, that no rope of any description can find its way into the propeller. The pick-up is made with the boat approaching from slightly off dead downwind with the mainsheet pinned amidships. The sail steadies the boat while the propeller maintains control, but it is important to keep the person in the water towards the ‘shoulder’ of the boat. A propeller can inflict traumatic injuries on a swimmer, which, in his already shocked state, could render the object of the whole exercise somewhat futile.

With a conscious and uninjured casualty it is always better to lose the last of your way five yards from him and toss him a line, than to risk injuring him by direct contact in a seaway.

With a conscious and uninjured casualty it is always better to lose the last of your way five yards from him and toss him a line, than to risk injuring him by direct contact in a seaway.

Probably the most difficult man-overboard scenarios occur when you are on a run, either with spinnaker set, or with a headsail poled out. There are a number of ways to deal with these undesirable situations depending upon the boat, the skill of her crew, her size and various other factors. It is therefore impossible to generalise. The only responsible answer is to consider deeply what you would do under these circumstances, then try your theory out in practice using a bucket and fender tied together as a dummy victim. If it doesn’t work, think again until you find something that does.

BRINGING THE CASUALTY ABOARD

BRINGING THE CASUALTY ABOARD

If the casualty is reasonably fit and the sea state not abominably rough, the first option would be to use a boarding ladder of the type fitted to many modern yachts or carried by them. So long as its steps reach well below the surface, a fully clothed swimmer has a good chance of climbing back aboard by timing his efforts to coincide with the boat’s movement in the waves. If the ladder is rigged aft, it is easier to climb with the yacht rolling in the trough than if she is held head-to-wind, pitching violently.

There are two schools of thought on boarding by stern ladder in a seaway. Some people’s experience is that the technique is surprisingly effective, but you should be aware that certain boats are apt to bring their sterns down with a wallop on anyone manoeuvring in the water.

If you have no ladder and your casualty is in good shape, the first thing to try – assuming you cannot simply manhandle him over the rail (always the premier option if there is enough muscle on board) – is to lower a bight of line into the water. The tail of a jib sheet is ideal. The swimmer steps in this and, as the boat rolls, heaves himself up as best he can while you take up the slack around a cockpit winch. After two or three bursts of effort he is usually high enough to roll under the top guard rail. The lower rail should be let go to make the job easier, which is a very good reason for lashing the ends rather than tensioning them up with a rigging screw. A lashing can be quickly cut in an emergency.

In some circumstances, a bowline to put a foot in is better than a bight of sheet. It depends on the shape of the boat, the height of the lift, etc.

If the man overboard is unconscious or injured, the first priority will be to secure him alongside. As usual with seamanship, methods will depend on circumstances, but a serious option to consider if the yacht has high freeboard is as follows: attach the lightest crew member to a spare halyard, sitting securely in a bosun’s chair in a deflated life jacket. Lower him over the side with the topping lift in hand. He secures the topping lift to the victim via whatever lifting system is to be applied (see below). Be ready to give the crew member plenty of slack in case he has to swim a few yards, but do not let him become detached. Winch him back on board with the most powerful winch available, then transfer the topping lift to the same winch and hoist the casualty with care.

For this to work, the boat must have at least two lines that can be made available from aloft. I have suggested the topping lift as one of these as it is pretty typical. If you are serious about real safety on board and are intending to sail out of reach of SAR, then perhaps you should consider making sure these are rigged and ready.

With any but a fit person in full possession of all faculties in the water, you will now have to devise a lifting arrangement of some sort. As mentioned above, the ideal is to go straight to an electric winch in the cockpit. While by no means standard equipment, power foredeck windlasses are now becoming the norm on larger yachts. If you have one of these, it is vital that at least one halyard or the topping lift is long enough to be led to it via snatch blocks to recover a casualty from the water. Failing power assistance or a winch big enough to wind up by manpower, a tackle must be employed.

The purchase must be at least 4 : 1 ratio. When overhauled it should be sufficiently long to reach the water comfortably, allowing for wave action, when its upper block is raised well above the level of the rail by a halyard. The halyard is shackled to the upper block and the lower block is attached to the swimmer, either to his harness, or to a bowline passed under his arms. The fall of the purchase is now led, via any necessary turning blocks, to a primary winch. The resulting power will enable a ten-year-old to lift a wrestler.

It is often suggested that the boom vang (or kicking strap) will serve well enough for this purpose. On some vessels it may, but generally speaking it is more sensible to carry a ‘dedicated’ tackle stowed somewhere convenient. It won’t cost a lot, you will find other occasional uses for it, and there will be no doubt that on the night when it might save a life, you’ll be glad you carried it.

Research on both sides of the Atlantic indicates that an unfit or badly debilitated casualty may be at risk from heart failure either during or shortly after being lifted from the water in a ‘standing’ attitude. It is far safer to hoist in a prone position if this is at all feasible. At least one commercial device is available that achieves this by means of a triangular ‘parbuckling sling’. One side of the triangle is tied to the toerail while the opposite angle is attached to a halyard. The casualty is manoeuvred into the bight of material thus formed then hoisted out.

The whole business of bringing an MOB casualty back aboard once ‘safely’ along side can sound glib in a textbook. The reality is very different and many lives have been lost from crews’ inability to manage it. The only sure route to confidence in your planned system is to try it out on a summer’s day when a volunteer feels up to a swim.

SEARCH AND RESCUE

SEARCH AND RESCUE

When you are sailing a large, fully crewed yacht within radio range of help, there is no doubt that you ought to designate a competent person to call for assistance immediately someone goes over the side. This does not mean that you are capitulating your control of the situation, but it enables you to concentrate more fully on retrieving the casualty in a situation where every minute, indeed second, may count. However, if a helicopter or lifeboat scrambles and your attempts fail, they will be with you that much sooner, which is very definitely what they prefer.

Where your boat is short-handed, especially two-handed, leaving you alone, the situation is not so clear cut. It is up to you whether you risk losing sight of a casualty while you radio for assistance. My own feeling is that under these circumstances a competent sailor should do all in his power to effect his own rescue, but remain aware that assistance can be called should matters turn ugly. The point at which you take time out from your efforts to call the search and rescue people will demand the coolest judgement you will ever have to make.

If you have GMDSS radio, it may well make sense to crash stop, deploy your safety gear, then nip below very quickly to activate the red button and note the time before returning on deck to go into your recovery routine. Don’t stop to fill in the details of your distress. Just send the automatic broadcast, then get back out there and stay in touch with the casualty. Grab the hand-held radio, but only so long as you can do it quickly, because you simply must not lose sight of your shipmate. As a rule of thumb, you should be seriously considering further radio procedure (or initial Mayday calls if you’ve no GMDSS) after two failed passes or a first abortive attempt to hoist a casualty you have brought alongside. If you have thought through your drill, however, and have practised it thoroughly so that you know it works, the question will probably never arise.

If you are wondering whether or not to clip on, do it.

If you are wondering whether or not to clip on, do it. When you are sailing in open water and conditions are such that you would consider reefing the mainsail, clip on at any time you leave the cockpit.

When you are sailing in open water and conditions are such that you would consider reefing the mainsail, clip on at any time you leave the cockpit. In gale or near-gale conditions when a knock-down seems even a remote possibility, everyone on deck or in the cockpit should be clipped on.

In gale or near-gale conditions when a knock-down seems even a remote possibility, everyone on deck or in the cockpit should be clipped on. Clip on when approaching an area of tidal disturbance. It may be worse than you expect.

Clip on when approaching an area of tidal disturbance. It may be worse than you expect. Even in fair weather, clip on at night.

Even in fair weather, clip on at night. THE REACH-TURN-REACH

THE REACH-TURN-REACH