Have a good feel for the basic chemical equation in soap-making.

Have a good feel for the basic chemical equation in soap-making.Chemistry can be intimidating. However, it is possible for a layperson to learn enough about chemistry to become a better soapmaker without becoming an expert, and without becoming bored!

After reading this chapter, you should:

Have a good feel for the basic chemical equation in soap-making.

Have a good feel for the basic chemical equation in soap-making.

Understand how to use certain scientific charts to predict the soap characteristics produced by various fats and oils.

Understand how to use certain scientific charts to predict the soap characteristics produced by various fats and oils.

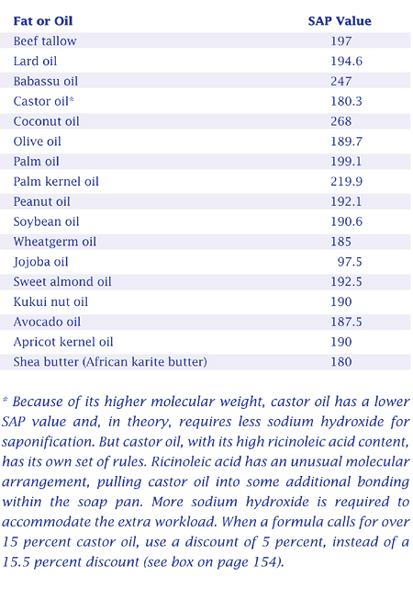

Understand how to use the SAP Value Chart to determine the approximate amount of sodium hydroxide you will need for a particular soap formula. You do not have to understand the chemistry to make soap, but the knowledge is helpful and can even be fun.

Understand how to use the SAP Value Chart to determine the approximate amount of sodium hydroxide you will need for a particular soap formula. You do not have to understand the chemistry to make soap, but the knowledge is helpful and can even be fun.

The soapmaking process is simply the combination of an acid and a base to form a salt. Something acidic combines with something alkaline to form something neutral — in this case, a mild bar of soap. In soapmaking, the oils and fats are the acids, sodium hydroxide is the base also known as the alkali, and soap is the salt of the particular acids used.

Consider, first, the chemical makeup of the fats and oils. For the cold-process soapmaker, each fat or oil consists of a different combination of triglycerides, compounds made up of three so-called fatty acids, linked to one molecule of glycerol (a form of glycerin). For example, olein is a triglyceride consisting of three molecules of oleic acid and one molecule of glycerol. A fatty acid is a different combination of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. For example, oleic acid is a fatty acid consisting of 18 carbon atoms, 34 hydrogen atoms, and 2 oxygen atoms. Most often, a triglyceride contains two or three different fatty acids, rather than three of the same kind.

Consider, next, the chemical makeup of the base. For the cold-process soapmaker, the common base is sodium hydroxide. Sodium hydroxide is a combination of one sodium ion and one hydroxide ion. The hydroxide ion consists of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom. It is the hydroxide ion, not the sodium ion, which is most critical to soapmaking. Other bases could be used instead of sodium hydroxide, because, again, it is the hydroxide ion which reacts with the acid to make soap.

Stirring the mixture is critical, and directly affects the time required for saponification. Though it is possible to have a few momentary breaks in stirring, consistent, brisk stirring allows the free fatty acids to continue to react with the free alkali. Without this nearly constant contact of the reactive ingredients, the process slows down.

When fats and oils react with sodium hydroxide, what is really happening is that triglycerides are releasing glycerin, permitting the remaining fatty acids (so-called free fatty acids) to combine with hydroxide ions to form soap.

Note that in cold-process soapmaking, the glycerol attached to the fatty acid is released and remains in the soap in the form of glycerin. Glycerin is a marvelous additive which moisturizes the skin. Industrial manufacturers either remove this glycerin and sell it as a by-product, or make soap with free fatty acids (without glycerin) rather than with triglycerides (which include glycerin). This is just one more reason why homemade soap can be so much finer.

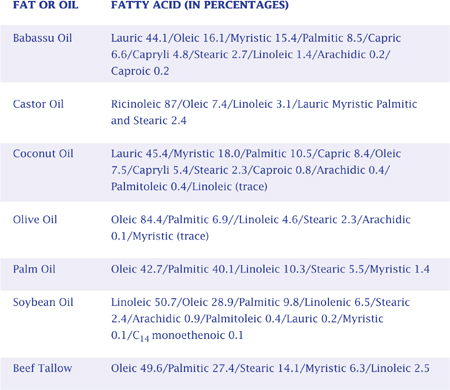

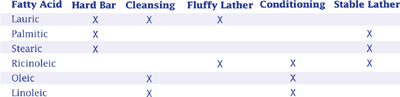

The major characteristics we look for in a soap — the hardness of the bar, the fluffiness of the lather, and the stability of the lather — depend upon which fatty acids are involved. Each fat or oil is a unique combination of several different fatty acids. The characteristics contributed by a particular fat or oil are determined by the characteristics of its predominant fatty acid(s). For example, palm oil consists of 40.1 percent palmitic acid — a fatty acid which increases the hardness of a bar. That’s why palm oil is known for contributing to a hard soap. Once you know the fatty acid makeup of the fats or oils in a soap formula, you can figure out what characteristics the soap will have. The following charts will assist you in this process.

As these charts indicate, no one fat or oil has all of the characteristics soapmakers find desirable in their soap. Thus, soapmakers must combine different fats and oils to produce the desired outcome. This is where the skill and artistry of the soapmaker is most tested. Mixing fats and oils also affects the amount of sodium hydroxide required to properly complete the reaction, as discussed on page 155.

THE FATTY-ACID MAKEUP OF SOME COMMON FATS AND OILS

SOAP CHARACTERISTICS PRODUCED BY VARIOUS FATTY ACIDS

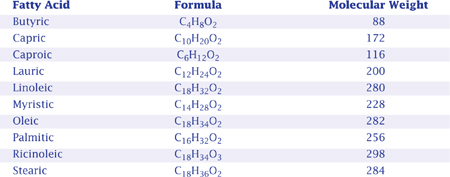

MOLECULAR WEIGHTS OF FATTY ACIDS

If you know the molecular weight of a fatty acid in your soap, often you can predict the lathering ability of your soap. In general, the greater the molecular weight of a fatty acid, the less fluffy and more stable the lather.

For example, beef tallow makes a thin lather. It consists of 24.6 percent of palmitic acid and 30.5 percent of stearic acid which have relatively high molecular weights of 256 and 284.

The molecular weight chart can help predict other soap characteristics as well. In general, as molecular weight increases, a fatty acid’s cleansing capability decreases, its potential to cause skin irritation decreases, and its hardness increases. Also, and the significance of this will be discussed below, the greater the molecular weight, the lower the SAP value.

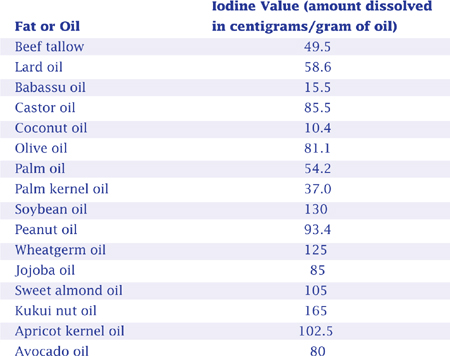

The iodine value measures an oil’s or fat’s saturation. More specifically, it indicates the amount of iodine chloride the fat or oil could dissolve, expressed in centigrams of iodine dissolvable per gram of oil or fat. Saturated fats have low iodine values and unsaturated oils have high iodine values. Though exceptions occur, fats with low iodine values make the hardest soaps. Thus, for example, palm oil makes a hard soap and olive oil makes a softer soap.

Each fat or oil has a saponification value (referred to as “SAP value”). The SAP value is actually a range of numbers, but the average of these numbers is usually presented on a chart. The SAP value of an oil or fat measures the amount of potassium hydroxide (chemical symbol KOH) in milligrams required to saponify (to react with and make soap out of) one gram of that oil or fat. So the SAP value divided by 1,000, multiplied by the weight of the oil equals the weight of potassium hydroxide required for saponification. For example, the SAP value of olive oil is 189.7. This means that 189.7 milligrams of KOH are required to completely saponify one gram (1,000 milligrams) of olive oil. The higher the SAP value, the more base required for saponification.

SAP VALUE CHART FOR COMMON FATS AND OILS

From the SAP value you can determine also how much sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is required for saponification, with some simple arithmetic and an understanding of basic soapmaking chemistry. Saponification is affected by the number of hydroxide ions in the solution. One molecule of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) has the same number of hydroxide ions (one) as one molecule of potassium hydroxide (KOH), but since KOH is heavier than NaOH, saponification requires less (by weight) of NaOH. More precisely, because the molecular weight of NaOH is 40 and the molecular weight of KOH is 56.1, the required weight of NaOH is  of the required weight of KOH.

of the required weight of KOH.

Weight of NaOH required =  weight of KOH required

weight of KOH required

So far, the science and mathematics are reassuringly precise. Unfortunately, there is one additional complication which introduces some uncertainty. The above formula indicates how much sodium hydroxide is required to completely saponify an oil. However, the soapmaker does not want to completely saponify the fats and oils — you want some fat and oil to remain unsaponified. This makes the soap milder, less caustic, and more soothing.

HOW MUCH SODIUM HYDROXIDE (NaOH) DO I NEED?

Suppose you want to saponify 10 pounds of olive oil. To figure how much sodium hydroxide is required, begin by looking up the SAP value.

Since the SAP value of olive oil is 189.7 (189.7 milligrams of KOH required per 1,000 milligrams of olive oil), multiply 10 pounds of olive oil by .1897; to figure the amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH) required — 1.897 pounds.

The next step is to multiply the amount of KOH required by the fraction  to figure the amount of sodium hydroxide required — 1.35 pounds.

to figure the amount of sodium hydroxide required — 1.35 pounds.

The final step is to multiply the amount of sodium hydroxide required for complete saponification by 84.5 percent (or whatever discount you find works), to produce a superfatted soap.

Our skin’s mantle is slightly acidic, anywhere between 4.00 and 6.75 on the pH scale (with pH 7 being neutral). Though our skin can tolerate a wide range of pH values, including some of the alkaline values, too much sodium hydroxide can be harsh. By using less sodium hydroxide than the SAP values suggest, and an excess of oils and nutrients, the bars are left with unsaponified oil within — this soap is gentle and moisturizing. See page 131 for more information on pH values.

The question is, how much less sodium hydroxide should be used? That is, after applying the formula on page 154 and determining a precise amount of sodium hydroxide for complete saponification, how much should the precise amount be discounted? I cannot give you a neat answer here. I have searched for a single discount I could apply consistently, but haven’t come up with one. I’ve worked with discounts ranging from 7 percent to 20 percent. The bigger the discount, the less base used, resulting in a milder soap that will also become rancid more quickly. When I do my calculations for a new soap formula, I usually begin with a 15.5 percent discount. This will provide a good approximation of the amount of sodium hydroxide required, but you will still have to experiment.

The SAP value calculations outlined earlier were for saponifying a single oil. But a soapmaker will never use just a single fat or oil — you always will be combining fats and oils to achieve a desired effect. To determine how much base to use in a soap formula with several fats and oils, you must calculate the SAP value for the entire mixture of fats and oils. A simple weighted average calculation can be made, as follows.

Suppose a soapmaker wishes to combine five pounds of olive oil, three pounds of coconut oil, and two pounds of palm oil. How much sodium hydroxide should be used? The following are the steps to take to figure this amount:

1. Determine the SAP value for the mixture of oils. Using the SAP value chart and the percentage by weight each oil contributes to the whole mixture, calculate the combined SAP value.

0.5(189.7) + 0.3(268) +0.2(199.1) = 215

2. Multiply the total weight of the oils by the combined SAP value to determine the amount of potassium hydroxide required.

(10 pounds) by 0.215 (215 divided by 1000) = 2.15 pounds

3. Multiply 2.15 pounds (the pounds of potassium hydroxide required) by the fraction  to determine the pounds of sodium hydroxide required for complete saponification.

to determine the pounds of sodium hydroxide required for complete saponification.

2.15 pounds x  = 1.53 pounds (of sodium hydroxide)

= 1.53 pounds (of sodium hydroxide)

4. Multiply the result from Step 3 by 84.5 percent (to reflect the 15.5 percent reduction discount I typically apply to leave some unsaponified fats and oils) to find the final answer for the amount of sodium hydroxide required.

1.53 pounds x 84.5% = 1.29 pounds

Again, remember that this 15.5 percent reduction discount means that excess fat is left in the soap, too much of which causes rancidity. If you have this problem, you would notice it after six to twelve months. Fortunately, there’s a solution. Adding preservatives — and natural preservatives are available — can postpone rancidity.