Hundreds of inventors, at different times, contributed to the creation of the railroads, but one individual stands out, not because he was the cleverest or the most innovative, but because he was the best at exploiting the ideas of others and turning them into workable concepts—George Stephenson. Born in modest circumstances in Wylam, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, he was a barely literate, self-educated man who did not suffer fools gladly, but who deserves the title of “father of railroads”, even though he made no significant inventions of his own. He played an important role in the development of two important lines: the Stockton and Darlington, completed in 1825, which was really the last and most sophisticated of the wagonways (see From Wagonways to Railroads); and the Liverpool and Manchester, whose opening five years later heralded the real start of the railroad age. He continued to play a vital role in the spread of the railroads, both in Britain and abroad, until his death in 1848.

Stephenson started out as a pit boy, but he soon realized that in order to progress he needed engineering skills, and he learned these initially with the help of a local schoolmaster. Before long, he found work as an engine wright and was put in charge of all the stationary engines at Killingworth, a large coal mine in Northumberland. He quickly realised that the key to making better use of steam technology was to enable the engines to run on rails and haul loads directly, rather than using the cable system, whereby stationary engines reeled in cables attached to cars (see Cable railroads), and he persuaded the colliery owners to give him the means to build a “traveling machine”—his name for the locomotive. The result was unveiled in 1814—a steam engine somewhat oddly named Blücher after Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, a Prussian general who led his army to several victories against Napoleon, the common enemy of Britain and Prussia at the time. Incorporating features from Trevithick’s engines (see Richard Trevithick), Blücher was built in the colliery shop and proved to be more powerful than any of its predecessors, as it could haul 30 tons (30.5 tonnes) of coal up an incline at 4mph (6.5kph).

The success of Blücher spurred Stephenson to build another 16 locomotives over the next 10 years, most of which were commissioned by local collieries. One went to the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway in 1817, but was withdrawn because it damaged the line’s cast-iron rails. The same fate befell a second engine that was sent to the railroad at Scott’s Pit at Llansamlet, near Swansea, in 1819. These failures demonstrated the great difficulty in developing engines that were light enough not to break the primitive tracks, but powerful enough to haul a reasonable load. Showing his versatility as an engineer, Stephenson initially solved this problem by using steam pressure to create a “steam spring” to cushion the weight of the load. He then simply increased the number of wheels to distribute the weight. In 1820, Stephenson was hired to build an 8-mile (13-km) railroad at Hetton colliery. The result was a train that relied on gravity on the downward slopes and steam locomotion on the level or uphill sections. It was the first railroad that used no animal power whatsoever.

However, Stephenson’s engines continued to have difficulties, and he did not have the resources to solve them. In the early 1820s, he became quite despondent, but then developments in the coal town of Darlington lifted his spirits. A group of prosperous Quaker colliery owners, led by Edward Pease and his son Joseph, wanted to create a railroad that would connect Darlington to Stockton at the mouth of the River Tees, where coastal shipping from London docked. They wanted to reduce the price of coal by making it cheaper to transport, and to counter an alternative plan that was being discussed to build a canal. Stephenson was the obvious man to prepare such a route and build the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and was summoned to the Peases’ home to discuss their plan. He was duly appointed surveyor and engineer on the project, and, since he had formed a company in 1823 with his son, Robert, to build locomotives at a works in Newcastle, he could use his own engines on the railroad. Nevertheless, when Stephenson surveyed the area to be crossed, he encountered considerable opposition from local landowners and had to map out a route that would avoid their fox-hunting grounds.

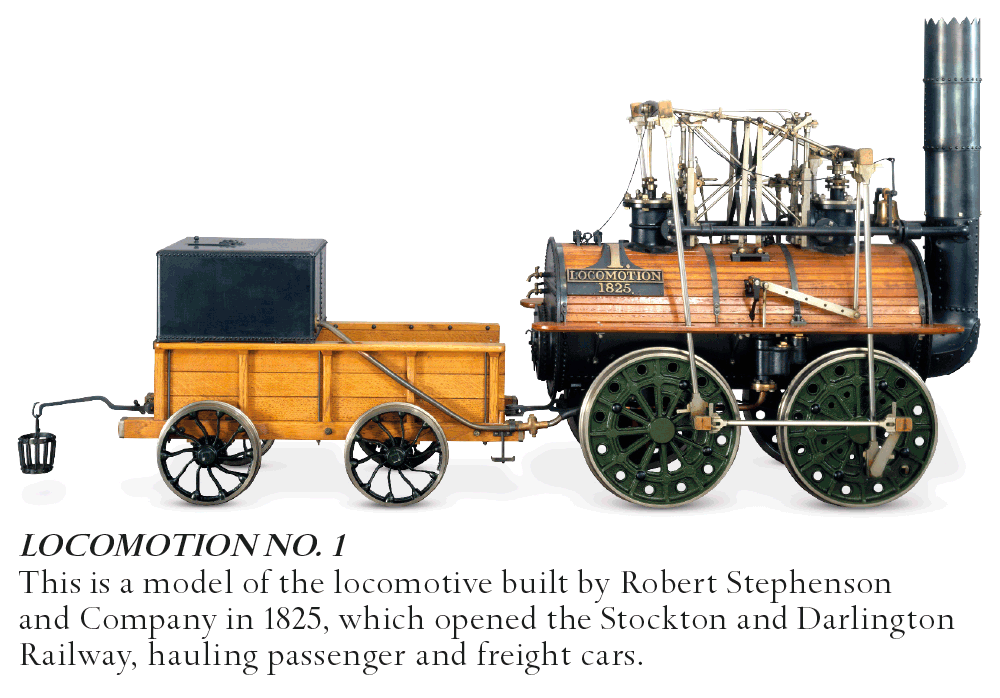

The plan was far more ambitious than any of the former wagonways. Nearly 37 miles (60km) of track had to be laid, and there were major physical obstacles too, notably the Myers Flat swamp and the Skerne River at Darlington. Stephenson eventually created a firm base in the swamp by filling it with tons of hand-hewn rock, and called on a local architect to help him design a stone bridge to cross the river. Despite its length and logistical difficulties, the line took only three years to construct, but even as it opened debate raged over what form of traction to use. Stephenson and his son produced the steam engine Locomotion No. 1, which, on the opening day of June 27, 1825, pulled a train of 34 cars carrying 600 passengers and a variety of goods through the countryside. However, this was not enough to convince the Peases. The truth was that Stephenson’s locomotives were unreliable—they often ran out of steam and frequently needed repairs—so most of those early trains were hauled by horses; at one point, the Peases even considered turning the whole line over to horse-driven trains. Eventually, however, a much better engine designed by an engineer at Stephenson’s works, Timothy Hackworth, saved the day, and it was the horses that were phased out.

The completed Stockton and Darlington Railway was recognized as a major technical advance over its predecessors, but, given the use of horses, it was still effectively a superior type of wagonway. It was also flawed. It had few sidings—which allow trains traveling in opposite directions to pass each other—so arguments and even fights between drivers were common. The owners also made the mistake of allowing anyone who was prepared to pay a fee to use their vehicles on the line, which meant that all kinds of conveyances, rickety and unstable, were used, resulting in frequent breakdowns. Nevertheless, the railroad attracted a lot of traffic, and, although it took time to become profitable, it established an important precedent—Stephenson had decided on a gauge of 4ft 8½in (1,435mm), which became standard across much of the world’s railroad network.

The heavy traffic on the Stockton and Darlington line encouraged entrepreneurs across Britain to promote local railroad plans. Many of these were never built, but the most important became Stephenson’s next big project—the Liverpool and Manchester line, which was conceived on a much larger scale than the Stockton and Darlington and would become the world’s first modern railroad. A group of wealthy industrialists in the northwest of England, annoyed at paying local canal owners’ extortionate rates to transport their goods, sought to link the two towns with a railroad. The 31-mile (50-km) line was much more ambitious than the Stockton and Darlington, and although originally conceived as a freight railroad, it would also carry passengers, as it linked two very important towns that had a combined population of 350,000. To ensure reliability, the trains would be run directly by the company, which set the pattern for nearly all the lines of the future.

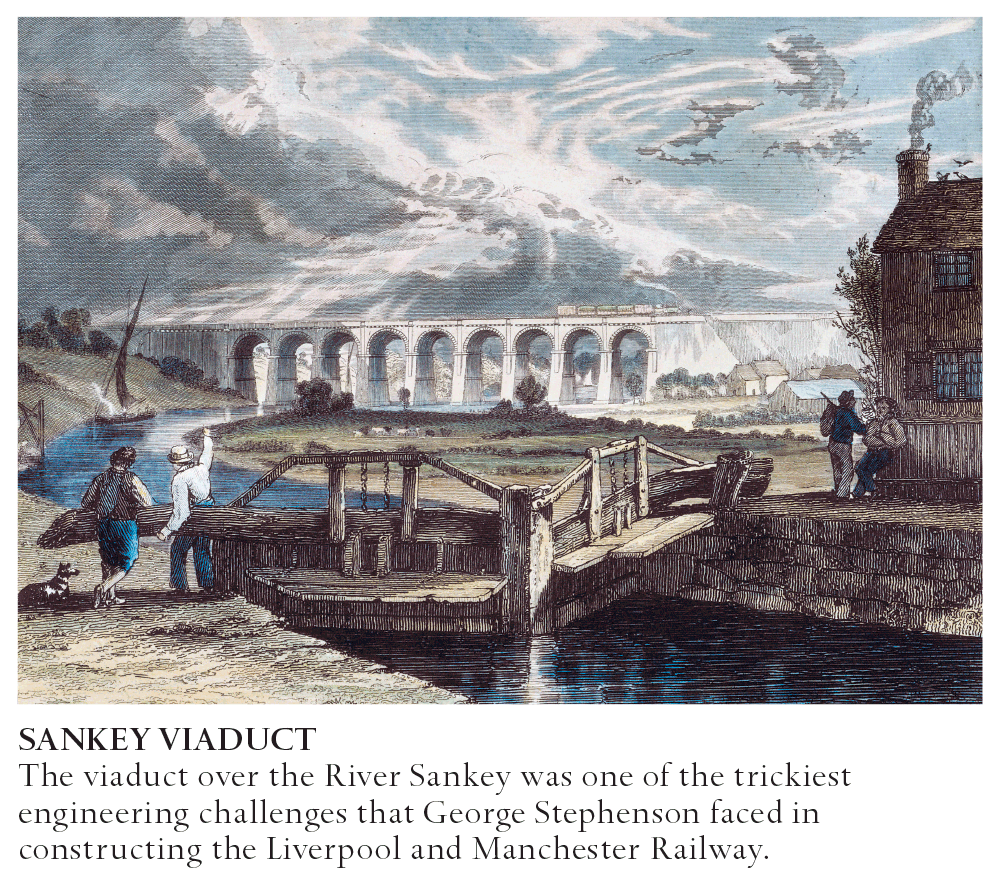

Stephenson was invited by the directors to determine the route. Again, there was a major area of swampy peat bog, Chat Moss, as well as a series of streams and rivers that needed fording, requiring no fewer than 64 bridges, including a nine-arch viaduct over the River Sankey. Nothing on this scale had ever been attempted before. Stephenson was again both surveyor and engineer, and personally studied the terrain. Local landowners violently opposed the line, and there was a false start when the initial Parliamentary Bill (which needed to be passed for the line to be built) was thrown out at the behest of the rival canal owners—partly a result of an embarrassing performance by Stephenson, who proved to be somewhat inarticulate in the intimidating atmosphere of Parliament. For a time, Stephenson was replaced, but he was soon reinstated, and work began in 1827. Stephenson personally oversaw construction all along the line, often riding long distances on horseback to check on progress. His solution to the Chat Moss problem was to float the railroad embankment on a bed of brushwood and heather. He also excavated a 2-mile (3.2-km) cutting through Olive Mount at the entrance to Liverpool, and built the Sankey Viaduct with sandstone blasted out of the cutting.

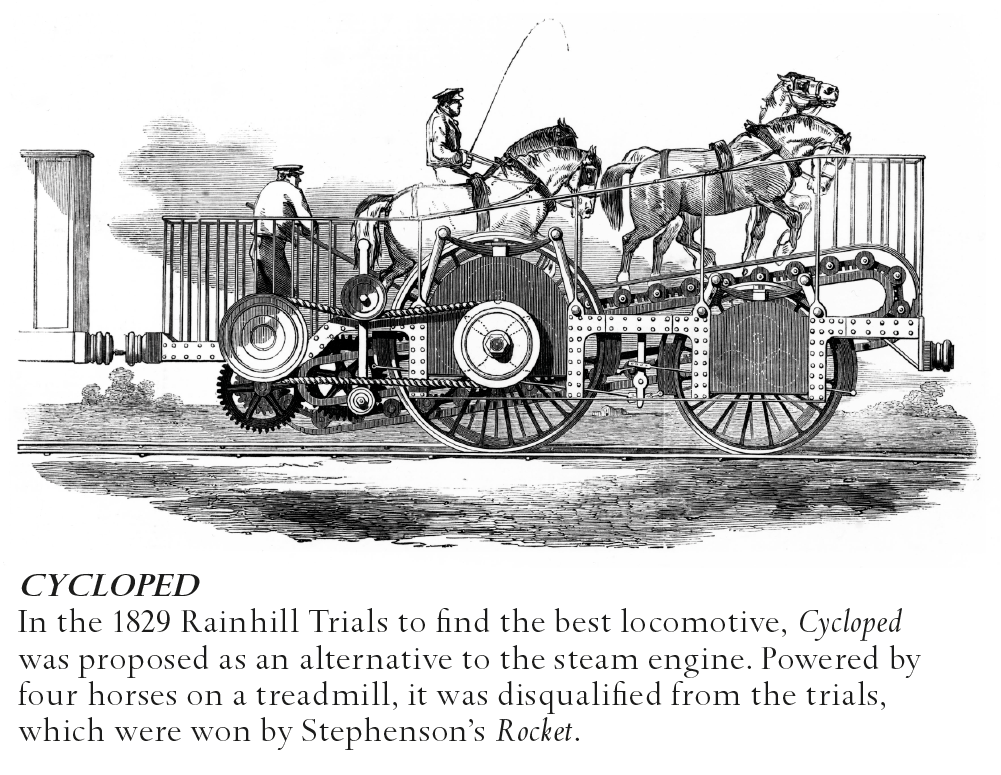

The form of traction to be used remained an issue throughout the line’s construction. The directors of the railroad favored locomotives, but were unsure whether the existing engines were up to the task, so they launched a competition, the Rainhill Trials, to decide who should design the engines for the railroad. Five entrants took part in the trials, which were held on a completed section of track on October 6, 1829, in front of 15,000 spectators. The technical requirements were strict, particularly regarding weight, which was fixed at a maximum of 6 tons (6 tonnes), and the engines had to complete twenty 2-mile (4-km) trips at an average speed exceeding 10mph (16kph).

One of the entrants, Cycloped, turned out to be a prank (the engine was in fact a horse on a treadmill), so Rocket, the entry of George Stephenson’s son, Robert, faced only three rivals: John Braithwaite and John Ericsson’s Novelty, Timothy Hackworth’s Sans Pareil, and Timothy Burstall’s Perseverance. In the event, the trial was easily won. Perseverance never managed more than 6mph (10kph), and the other two failed to finish the course. Meanwhile, Rocket thundered up and down the track, ensuring that the Stephensons won the £500 prize to help develop their engines.

Since the line carried freight in both directions—the raw materials from the port at Liverpool, and the goods being brought back—as well as passengers, it was double-tracked from the outset, which greatly increased capacity. The opening day on September 15, 1830 was an epoch-making event, attracting people from around the world, several of whom would return home to inspire the building of railroads in their own country. The celebrations, however, were marred by tragedy—an accident that resulted in the death of William Huskisson, a prominent politician. Huskisson crossed the tracks to greet the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, when the ceremonial trains stopped at Parkside, halfway down the line. Panic set in when another train, Rocket, approached. Huskisson failed to climb onto the Duke’s car in time, and fell under the oncoming train. His leg was shattered and, although Stephenson took him to Manchester for help—reaching an amazing speed of 35mph (56kph) en route—Huskisson died that evening.

Despite this tragedy, the completion of the Liverpool and Manchester marked the peak of Stephenson’s career, but it was by no means its end. He went on to build numerous railroads and his son, Robert, who concentrated mainly on improving the locomotives produced by Robert Stephenson and Company, constructed a far longer railroad, the 112-mile (180-km) London and Birmingham line, which is now part of the West Coast Main Line. The locomotive works thrived and eventually produced more than 3,000 engines before being absorbed by a larger company in 1937. George Stephenson also advised early American rail promoters (see early promoters), and assisted in the construction of lines in Belgium (see Belgium) and Spain. The Stephensons certainly left their mark on the railroads. When the line celebrated its 150th anniversary in 1980, the then-chairman of British Rail observed: “The world is a branch line of the Liverpool and Manchester.”