Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV) is one of those names from Russian history that most of us know, forever redolent of despotic ruthlessness and cruelty. Ivan Grozny (his name means ‘formidable’ or ‘awesome’, rather than ‘terrible’ in the modern sense) was born in 1530, the grandson of Ivan III, and proclaimed Grand Prince of Moscow at the age of three, following his father’s death. For fourteen years he watched and brooded as relatives and boyars ruled in his name. He later complained that he felt slighted and humiliated by those who dared to act on his behalf. He became introverted and resentful, given to fierce outbursts of rage and malice. It is this propensity for callous brutality that has marked Ivan’s historical legacy and it is undoubtedly true that it showed itself in the way he dealt with his enemies and rivals.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that Ivan Grozny was Josef Stalin’s favourite historical character (see here). Towards the end of the Second World War, when the film director Sergei Eisenstein began work on his film about Ivan, Stalin called him to the Kremlin for a pep talk. Since every word Stalin spoke was regarded as a pearl of wisdom and recorded for posterity, we have a verbatim record of their conversation.

Parts of it are amusing. Stalin takes it upon himself to give Eisenstein advice about acting and film-making. He complains that the director has made Ivan’s beard too long and pointy: ‘S.M. Eisenstein promised to shorten the beard of Ivan the Terrible in future,’ the transcript faithfully records. But other criticisms were not so simply answered, and it is easy to imagine Eisenstein’s growing panic as he is interrogated in a darkened Kremlin late at night by Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrey Zhdanov and the Great Leader himself:

Stalin: Have you studied history?1

Eisenstein: More or less …

Stalin: More or less! Well, I know a bit about history! … You have made the Tsar too weak and indecisive. He resembles Hamlet. Everybody tells him what to do … Ivan the Terrible was a great and a wise ruler: he always had our national interest at heart. He did not allow foreigners into his country … He was a nationalist Tsar and farsighted … By showing Ivan the Terrible the way you do, you have committed a deviation and a mistake.

Zhdanov: Your Ivan the Terrible comes over as a neurotic.

Stalin: You have to show him in the correct historical style. It is not correct that Ivan the Terrible kissed his wife for so long. At that time it was not permitted …

Molotov: One may show conversations, repressions but not this …

Stalin: It is true that Ivan the Terrible was extremely cruel. But you have to show the reasons why he had to be cruel.

Molotov: You have to show why repression was necessary. Show the wider needs of the state …

Stalin: One of Ivan’s big mistakes is that he didn’t finish off his enemies, the big feudal families. If he had destroyed these people then he wouldn’t have had the Time of Troubles. If Ivan the Terrible executed someone he repented and prayed for a long time. God disturbed him on these matters … But it is necessary to be decisive …

It is clear from Eisenstein’s film that he is partly portraying Stalin in the figure of Ivan, and from the record of their conversation it seems Stalin was aware of this. The final version of the movie shows Ivan as cunning and decisive, not shrinking from repression and murder – one of its most dramatic scenes shows Ivan having his own cousin stabbed to death in the Kremlin – but always acting in Russia’s interests, unifying the country by the strength of his autocratic rule. Stalin thought the film should have made Ivan look even tougher, but he knew its vast propaganda value for a Russian nation locked in a life and death struggle with Nazi Germany.

With a script based loosely on historical documents and on the writings of one of Ivan the Terrible’s advisers, Ivan Peresvetov, Eisenstein turns the new tsar’s speech at his coronation in 1547 into a vision of how Russia must be governed. Only a ruler with unlimited power, Ivan says, can guarantee Russia’s survival:

For the first time2, a prince of Moscow claims the title of tsar of all the Russias, and puts an end to the divisions of the past when the boyars fought among themselves. From today the Russian lands shall be united. We shall establish an army with universal military service and all – all! – shall serve the state. Only a strong ruler can save Russia. Only strong rule and a united state can repel the enemies at our borders.

We can’t be certain of course that these exact words were really spoken by Ivan, but they encapsulate the autocratic principles that would characterise his rule and that of nearly every ruler after him. In a deeply poignant passage that addresses both the Russia of the sixteenth century and the Soviet Union under Nazi occupation, Eisenstein has Ivan speak directly to the camera:

For what is our country now?3 A body with severed limbs! We control the sources of our great rivers – Volga, Dvina, Volkhov – but their outlets to the sea are in enemy hands. Our territories have been stolen from us, but we shall win them back! From this day I shall be sole and absolute ruler, for a kingdom cannot be ruled without an iron hand. A kingdom without an iron hand is like a bridle-less horse. Broad and bounteous are our lands, but there is little order in them. Only absolute power can safeguard Russia from her foes – the Tartars, Poles and Livonians: pray for the unity of our Russian fatherland!

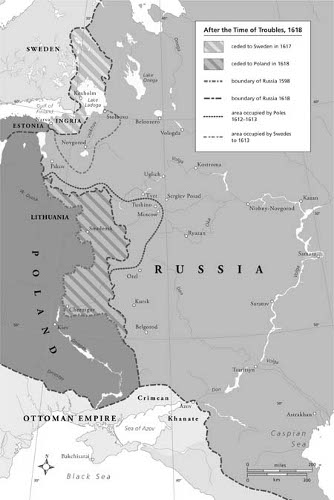

Ivan’s Russia was beset by powerful enemies – Catholic Lithuania and Poland in the west; Sweden in the north; Muslim powers in the south and east. Early in his reign he’d experimented with a national consultative council and local assemblies. But in what amounted to a condition of never-ending war, the fist of autocracy seemed Muscovy’s only hope for survival.

By the 1550s, Ivan’s sole foreign ally was England. He turned to Elizabeth I with epistles that sound almost like love letters; he offered her generous trade privileges in return for artillery and munitions, and he built a luxurious English embassy within the walls of the Kremlin for English merchants and diplomats. One ambassador, Giles Fletcher, wrote in his treatise Of the Russe Commonwealth of the astonishing unchecked power of the Russian tsar:

The form of their government3 is plain tyrannical! All are behoven to the prince after a most barbarous manner. In all matters of state – making and annulling public laws, making magistrates, the power to execute or pardon life – all pertain wholly and absolutely to the emperor, as he may be both commander and executioner of all.

The German traveller and writer Baron von Herberstein was even more scathing in his Notes on Muscovite Affairs, marvelling at how far Russia had diverged from the forms of governance he was familiar with in the West:

In the power which he holds5 over his people, the ruler of Muscovy surpasses all the monarchs of the whole world … He holds unlimited authority over the lives and property of all his subjects: not one of his counsellors has sufficient authority to dare to oppose him or even differ from him on any subject – in short, they believe he is the executor of the divine will.

But Herberstein was not quite right. We saw how Muscovy under Ivan III had unified the Russian lands in the fifteenth century, but some of the nobles – the boyar families who had previously ruled independent princedoms – continued to resent Ivan’s assumption of absolute power. Eisenstein’s film dramatises their plotting against him and, in another nod to Stalin, paints an approving picture of the tsar’s obsessive rooting out of treachery among his subjects:

We shall cut off heads without mercy6! We shall crush sedition and eradicate treason! … I stand alone – I can trust no-one … I will smash the boyars – take away their patrimonial estates and award land to only those who serve the state with distinction …

Ivan moved decisively against his opponents. He abolished the great hereditary estates that had been the powerbase of generations of princes: from now on, land would be granted – and taken away again – at the whim of the tsar, and ownership would be contingent on the recipient providing service to the state. The boyars were no longer consulted on affairs of government. All men outside the Church, including the nobility, were bound to lifelong service to the state; conscription was a universal duty, and the tsar’s authority in all matters was absolute.

But Ivan was racked with suspicion bordering on paranoia. He murdered his own son in a fit of rage; he blamed the boyars for the death of his wife Anastasia, and he was the founder of Russia’s first secret police – the Oprichniki – with unlimited powers to crush dissent, recruit informers and mete out summary justice. Under orders from Ivan7, the Oprichniki put several thousand people to death in Novgorod because the tsar suspected they’d been talking to his enemies in Lithuania.

At one stage, Ivan’s paranoia and hatred of the boyar families who challenged his right to rule with dictatorial powers led him to set up his own secretive state within a state, known as the Oprichnina, striking fear into the hearts of his opponents. In its ferocity and capriciousness Ivan’s reign of terror anticipated that of Stalin, who enthusiastically approved of his methods (see here). In his Kremlin interrogation of Eisenstein8, Stalin reproaches the director for painting a critical picture of Ivan’s secret police, insisting that they were ‘a progressive army’ and their leader Malyuta Skuratov ‘a hero’.

In fact, Ivan’s repressions alienated many of his former allies. His closest personal friend and greatest general – Prince Andrei Kurbsky – fled to Lithuania and, just as the exiled Trotsky would later do with Stalin, lambasted his former comrade in epistles from abroad:

To the Tsar, exalted by God9, who formerly appeared most illustrious but has now been found to be the opposite! May you, o Tsar, understand this with your leprous conscience … you have persecuted me most bitterly; you have destroyed your loyal servants and spilled the blood of innocent martyrs … You have answered my love with hatred, good with evil, and my blood – spilt for you – cries out against you to the Lord God!

Unlike Stalin, though, Ivan wrote back, and the correspondence between the two former friends is riveting. From the safety of exile, Kurbsky rails at the barbarity of Ivan’s autocratic regime, praising the superiority of the European civic society in which he now lives. Ivan replies contemptuously that such a system of government by consent could never work in a land as wide and unruly as Russia:

To him who is a criminal10 before the blessed cross of Our Lord, who has trodden underfoot all sacred commands … and completed the treachery of a vicious dog! In view of the power handed down to me by God is it the sign of a ‘leprous conscience’ to hold my kingdom in my hand and not let my servants rule? … The autocracy of this great Russian kingdom has come down to [me] by the will of God … and it is the Russian autocrat who from the very beginning has ruled all his dominions – not boyars and not grandees! … For the rule of many is like unto the folly of women; for if men are not under one single authority, even if they are strong, even if they are brave, it will still be like the folly of women! The Russian land is ruled by us, its sovereign, and we are free to reward our servants and we are free to punish them! … and the rule of a Tsar calls for fear and terror and extreme suppression.

Ivan the Terrible is remembered as a wild-eyed, slightly deranged figure. In his later years, he seems to have swung between volcanic fits of drunkenness and depravity and episodes of terrified repentance when he begged to be allowed to enter a monastery. Shortly before his death he was pestering Queen Elizabeth with marriage proposals and requests for asylum in London. When she ignored him, he flew into a rage, addressing her in most undiplomatic language: ‘I spit on you and on your palace11!’ Ivan’s anger at a minor dispute about trade spilled over into a personal attack on the Virgin Queen:

I thought you were the one who ran your own country. That is why I started this correspondence with you. But it seems other people are running your country besides you … You are still there in your virginal state like any spinster … Moscow can do without English goods …

Yet for all his faults, Ivan IV made a positive contribution to Russian nationhood, unifying a fractious state and dramatically expanding its borders. Under Ivan’s leadership, Russia expanded beyond the lands occupied by Orthodox, ethnic Russians. It conquered the Tartar khanate of Kazan, laying the foundations for Russia’s future empire: astoundingly, it would grow by 50 square miles a day for the next three centuries, until by 1914 it occupied 8.5 million square miles – a multi-ethnic, multilingual state spanning more than one-seventh of the globe.

By his death in 1584, Ivan had neutered the boyars and set Russia on the path of centralised autocracy. In Britain, Magna Carta may have curbed the rights of the monarchy and opened the way for a future of constitutional government, but in Russia the power of the sovereign would remain unfettered.

So deeply had the fear of internal division, and the concurrent menace of foreign invasion, permeated the Russian consciousness that the concept of a supreme ruler wielding absolute power was for the most part willingly accepted. The wealth and resources of society were commandeered for the needs of the state; peasants were tied to the land in the first steps towards full serfdom; villages and town communities were made jointly responsible for guaranteeing the payment of taxes, finding recruits for the army and keeping law and order. As we’ll see, this doctrine of joint responsibility – subjugating the individual to the common welfare – would become a permanent feature of the way power was wielded in Russia. The readiness to sacrifice personal interests for the good of the state helped lay the foundations of a collectivist ethic that has remained dominant.

‘The Muscovite state12,’ writes the nineteenth-century historian Vasily Kliuchevsky, ‘in the name of common welfare took into its full control all the energies and resources of society, leaving no scope for the private interests of individuals or classes.’ Compelling national need – the need for self-defence, for survival in the face of overwhelming odds – laid the foundations for a state that would become increasingly omnipotent. Karamzin, the avowed partisan of autocratic rule, concludes in his History of the Russian State (1816–26) that ‘Russia owes her salvation13 and her greatness to the unlimited authority of her rulers’. And Sir George Macartney – who served as British ambassador to Russia in the eighteenth century – would comment, with a mixture of admiration and reproach, in his book An Account of Russia: ‘To despotism Russia owes her greatness14 and her dominions, so that if ever the monarchy becomes more limited, she will lose her power and strength in proportion as she advances in virtue and civil improvement.’

Ivan the Terrible’s sidelining of the aristocracy left only the autocrat and his subservient people. No independent structures or institutions mediated power between them. The Church saw its property confiscated and its influence wane. No infrastructure of laws and rights and no civic society – no middle class – were allowed to form. This model of society would become a major obstacle to reform in Russia, separating her ever further from developments in Western Europe and defining the character of the Russian state for many centuries to come.