Moscow had held out. Christmas and New Year celebrations in the exhausted capital were muted. Yet Stalin seems to have exchanged acute depression for manic optimism. He told the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, that the war had reached a turning point:

The German army is1 exhausted. Its commanders hoped to end the war before winter and made no proper preparations for a winter campaign. They are poorly clothed, poorly fed and losing morale. But the USSR has massive reinforcements, which are now going into action … We will continue to advance on all fronts.

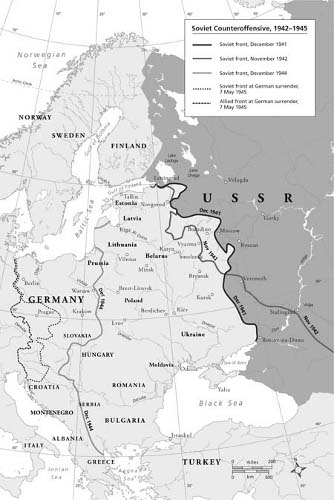

Stalin’s exuberance was not shared by the military. Marshal Zhukov’s troops had pushed the Germans back some 80 miles, but the momentum had not yet swung to the Soviets. Zhukov pleaded that the Red Army needed time to regroup; Stalin ordered an all-out counter-offensive. He told his generals they must emulate Kutuzov in 1812 and chase the invading armies out of the Russian lands. But the attack launched in January 1942 made little impact. The Soviet forces2 were too weak to dislodge the Germans, and by April the offensive was bogged down in the mud of the spring rasputitsa. Four hundred thousand more men were captured or wounded. Stalin was forced to abandon the campaign. The conflict settled into a brief stalemate.

The men at the front were not the only ones to suffer. Those left behind endured their own hardships. It was a rare family that did not have a father, son or brother away in battle, and by the end of the war few would escape without losing a relative. The longing and anxiety of the separated was captured in a poem by Konstantin Simonov, Zhdi Menya (Wait for Me3), which became as popular in Russia as the songs of Vera Lynn in Britain or Marlene Dietrich in Germany. Its hypnotic rhythms are a half-comforting, half-despairing prayer for the safe return of millions who would never come back:

Wait for me, and I’ll come back!

Wait in patience yet,

When they tell you off by heart

That you really should forget.

Even when my dearest ones

All say that I am lost,

Even when my friends give up,

And sit and count the cost,

Drink a glass of bitter wine

To their absent fallen friend –

Wait! And do not drink with them!

Wait until the end!

But the women of the Soviet Union did more than just wait. It fell to them to fill the gaps left in industry and agriculture. In December 1941, a new law mobilised all undrafted workers for war work. Overtime was made obligatory, holidays were suspended and the working day increased to 12 hours. Women between the ages of 16 and 55 took up the jobs left by the fighting men, stoking furnaces, driving tractors and operating heavy machinery.

More and more factories were being dismantled and relocated to the east, hastily reassembled in the Urals, Siberia, Kazakhstan and Central Asia. Millions of people were evacuated with them, plunged into a new life in an unknown region. Living conditions were harsh: factories were rebuilt first and accommodation second. Through the bitter winter of 1941–2, hundreds of thousands lived in mud huts and tents, as society responded to the slogan that appeared everywhere in posters, newspapers and speeches: ‘Everything for the front!’ In some cases, the machines were assembled immediately so production could begin, and only then would factory walls be built around them. But by mid 19434 industrial production had outstripped that of Germany. The output of munitions quadrupled between 1940 and 1944. In areas where Soviet industry was weak, such as the production of lorries, tyres and telephones, lend-lease supplies from the USA and Britain helped make up the deficit.

Food, though, remained a huge concern. The Germans now controlled much of the Soviet Union’s most fertile land and the Soviets needed to adapt quickly if they were to feed the army, let alone the rest of the population. Agricultural production had fallen catastrophically; the grain harvest of 1942 was only a third of 1940 levels. The Kremlin imposed demanding quotas on the collective farms but, unlike in the civil war, the peasants were allowed to keep their limited private plots and to sell their produce. As in industry, it fell to the women to take up the slack on the kolkhozy. The author Fedor Abramov wrote of the superhuman effort from all parts of society that kept Soviet agriculture afloat:

They dragged out5 the old men, they dragged teenagers from their school desks, they sent little girls with runny noses to work in the forests. And the women, the women with children, what they went through in those years! No one made any allowances for them, not for age or anything else. You could collapse and give up the ghost, but you didn’t dare come back without fulfilling your quota! Not on your life! ‘The front needs it!’

City dwellers cultivated every spare patch of earth to supplement their meagre diets with home-grown vegetables, and the Allies provided meat in the form of huge quantities of tinned Spam. Rations were now allocated only to those who turned up for work. The whole of Soviet society was regarded as a military machine, and unauthorised absence from work was classed as desertion, punishable, as it was at the front, by death. Local defence units and citizen fire wardens were recruited from women, adolescents and the elderly. Street fortifications were hastily built and militias assembled from factory workers. Private radios were confiscated for the duration of the war, and those who failed to hand theirs in were liable to be punished. ‘Praising American6 technology’ was declared an arrestable offence. (The USA may have become an ally, but old attitudes of wariness and mistrust died hard.) A whole new class of ‘crimes’, punishable by forced labour, was created, including ‘spreading rumours’ and ‘sowing panic’. Those who were convicted and dispatched to the Gulag joined the hundreds of thousands who had been deported from Poland and the Baltic states, all of them put to work helping the war effort, assigned to units building airports, landing strips and roads in the far north and east.

By the spring of 1942, the Nazi invaders had lost over a million men, and Hitler accepted he could not relaunch the three-pronged attack of Barbarossa. He decided instead to focus on taking the Caucasus oilfields, a vital goal if the Wehrmacht were to have enough fuel to continue the war. The Germans’ first task was to reach the Rivers Don and Volga, where they could cut off the supply route to the Soviet forces and cover their own flank as they pushed south towards the oil cities of Grozny and Baku. In early summer, Hitler’s forces repulsed a renewed Soviet offensive in Ukraine and began the advance eastward into the Don steppe. At the end of June, they planted the swastika on the peak of Mount Elbrus, the highest point in Europe. The Wehrmacht had ventured7 farther into Russia than any Western army before it, capturing nearly 2 million square kilometres of Soviet territory. In July, Hitler confidently told his generals ‘The Russian is finished.’

Stalin’s optimism of late 1941 was beginning to waver. By the end of July 1942, he was resorting to methods of the utmost ruthlessness to ensure the Red Army fought to the last drop of blood. His Order Number 227 was distributed to all units, with instructions that it be read to every fighting man.

The people of our country, for all the love8 and respect that they have for the Red Army, are beginning to feel disappointment in it; they are losing faith in it. Many curse the Red Army for giving our people over to the yoke of the German oppressors while the army runs away to the east. Some foolish people say we have much territory and can continue to retreat … But it is time to stop retreating … ‘Not a single step backwards!’ must be our motto. Each position, each metre of Soviet territory must be stubbornly defended, to the last drop of blood. We must cling to every inch of Soviet soil and defend it to the end. We must throw back the enemy whatever the cost. Those who retreat are traitors to the motherland. Panic-mongers and cowards must be exterminated on the spot.

Stalin ordered the summary court martial of any officer who allowed his men to retreat without express instructions from military headquarters. Offenders were to be stripped of their commission and medals and shot. To deter ‘cowards and panic-mongers’, penal battalions were created. ‘Those who have been9 guilty of a breach of discipline due to cowardice or bewilderment,’ said Stalin’s order, would be ‘sent to the most difficult sectors of the front to give them an opportunity to redeem by blood their crimes against the motherland.’ To prevent retreat in the face of the enemy, ‘blocking squads’ armed with machine guns were to be placed behind unreliable divisions. ‘In case of panic or scattered withdrawals of elements of the division, the squads must shoot them on the spot and thus aid the honest soldiers of the division to fulfil their duty to the motherland.’

Order Number 227 drew on the historical Russian precept that the individual must be prepared to sacrifice himself for the greater good of the state. Its rhetoric of ‘redemption through blood’ – iskupit’ krov’yu in Russian – is that of the medieval chronicles, redolent of Russian history right back to the martyrdom of Boris and Gleb (see here). Penal battalions were assigned to the most perilous tasks, such as clearing minefields in front of Soviet advances or laying mines in the path of German tanks. Inmates from the labour camps were offered the chance to expunge their convictions by serving in them. Casualty rates were as high as 50 per cent, and the chance to win redemption was often a moot point.

More than 150,00010 men were sentenced to death for ‘panic-mongering, cowardice and unauthorised desertion of the battlefield’. Stalin took to phoning commanders to ask why they were not implementing his orders. Order Number 227 had the desired effect. It imposed discipline and unity, boosting morale among the troops. Its twin mottos – ‘Not a step back!’ and ‘Victory or death!’ – would define the ethos of the Red Army for the rest of the war.

The state was more than willing to use fear to get the necessary results. When Nikolai Baibakov, who later became the head of the State Planning Committee Gosplan, was put in charge of the oil installations in the Caucasus, he was warned by Stalin ‘If you leave11 the Germans even 1 ton of oil, we will shoot you. But if you destroy the installations and we are left without fuel, we will also shoot you.’

But self-sacrifice could be motivated by love as well as by fear, and the Kremlin was adept at tapping into the deep well of Russian patriotism. The conflict was given the official title ‘The Great Patriotic War’ to summon up thoughts of ‘The Patriotic War’ against Napoleon. New decorations were created with the names of historic heroes – the Orders of Suvorov, Kutuzov and Nevsky – and gold braid reintroduced on military uniforms. Political commissars were made subordinate to military commanders; and troops were instructed to go into battle with the cry ‘For the motherland and for Stalin!’ The appeal to Russianness threw up a problem. It excluded the non-Russian nationalities, who were also fighting in the armed forces. Appealing to ‘Soviet-ness’ had a much less powerful ring to it; for many ethnic minorities, it even had distinctly negative connotations. The propaganda machine went into contortions to try to resolve the dilemma. The non-Russian nationalities were encouraged to ‘join in with your Russian brothers’. ‘The home of the Russian is also your home12,’ they were told. ‘The home of the Ukrainian and Belorussian is also your home!’ Stalin, himself a Georgian, spoke of the Russian people as the outstanding force and the leading nation among all the Soviet peoples. The unspoken promise to the lesser nations seemed to be that they would enjoy freedom and equality if they pulled their weight during the war. And, to an extent, it worked. Cooperation among the nationalities increased in the face of a common enemy. For 20 years the ‘brotherhood of nations’ envisaged by the revolution had been little more than words, but during the Great Patriotic War, for a brief moment, it looked close to being realised.

It was, though, always Russia at the heart of the equation. In 1943, the politburo decided to replace the ‘Internationale’ – with its appeal to supranational values of class struggle – with a new national anthem that proclaimed Russia’s leading role in the Union:

An indestructible union13 of free republics,

Was bound together by Great Rus!

Long live the land created by the will of the peoples:

The united, powerful Soviet Union!

Sing to the motherland, home of the free!

Fortress of peoples in brotherhood strong!

Stalin’s priority was the need to unite the nation. That is why he hinted at concessions to the nationalities and why he made compromises in other areas of society. He permitted more freedom in culture. Artists could create what they wanted, as long as their work avoided direct criticism of Marxism–Leninism. Previously banned poets were allowed to publish again. Anna Akhmatova broadcast her emotional, patriotic verse on Soviet radio. Composers who not so long ago had been denounced by the Kremlin contributed music to the nation’s cause. Shostakovich began writing his Seventh Symphony, a tribute to his native Leningrad, while he was serving as a part-time fire warden in the besieged city. Like Akhmatova, he was evacuated to safety and finished the work in the town of Kuibyshev, announcing over the radio: ‘All of us are soldiers14 today, and those who work in the field of culture and the arts are doing their duty on a par with all the other citizens of Leningrad.’ When the symphony was performed in the Large Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonia on 9 August 1942, the city had been blockaded for nearly a year and audience and musicians alike were close to starvation. The brass section had to be given extra rations to play. The Soviet leadership announced that the symphony represented an artistic denunciation of the evils of Nazism. They ordered a bombardment of German positions to halt the shelling of the city during the performance, which was broadcast on loudspeakers in the streets and subsequently around the world. The Leningrad is far from Shostakovich’s most accomplished work, and he later claimed it was a denunciation of all dictatorships – communist as well as fascist – but it gave a powerful boost to Soviet morale.

Even the Orthodox Church, the reviled target of Communist disapproval, long driven underground, was allowed to resume open worship. The Russian patriarchate, abolished by the tsars, was restored. Priests were encouraged to say prayers for the triumph of the Soviet army and to raise money for the war effort. Tanks on the way to the front were often blessed. Stalin insisted that priests and bishops be subjected to official vetting and they had to swear loyalty to the Soviet state. But the Church did not resist his demands and a tacit pact was reached between Church and State – some would call it collaboration – which has endured until today. The then Metropolitan of Moscow, Nikolai, customarily referred to Stalin as ‘our common father15’.

The concessions by the Kremlin, and the carefully fostered atmosphere of national reconciliation, convinced many that they could at last have a say in the destiny of their own country. The novelist Vyacheslav Kondratiev, himself a veteran, wrote: ‘For us, the war16 was the most important thing in a generation… You felt as if you held the fate of Russia in your hands. It was a real, genuine feeling of citizenship, of responsibility for your fatherland.’

The German Sixth Army, under the command of the experienced General Friedrich von Paulus, reached Stalingrad on the banks of the River Volga in August 1942. Hitler made no secret of his determination to capture the city that bore the name of his hated enemy. It was as if the two dictators were about to engage in a personal duel to the death.

Stalin told his generals, ‘The defence of Stalingrad17 is of decisive importance to all Soviet fronts. The Supreme Command orders you to spare no effort, to shirk no sacrifice in the struggle to defend it and destroy the enemy.’ The battle had been18 given added urgency following a visit to Russia a few days earlier by Winston Churchill and the US representative Averell Harriman. The noise from the engines of the US Liberator bomber in which the two men flew from Cairo to Moscow had evidently made conversation impossible, and they communicated by notes written in pencil. Reading those scribbled pages now, it is clear they were bringing bad news: Churchill and Harriman informed Stalin that the Western Allies were still not ready to open a second front in Europe. The Red Army would have to face the Germans alone in the East for at least another year.

The defence of Stalingrad was entrusted to the newly formed 62nd Soviet Army under the command of General Vasily Chuikov, a grizzled 42-year-old who had fought in the October Revolution of 1917 and later in Poland and Finland. Chuikov’s memoirs, The Battle of the Century (1963), are a rather deadpan account of his role in the fighting – you would hardly guess the heroism of the man – but he did allow himself the odd flash of emotion. The first came on the eve of the battle, when he made a personal promise to Stalin. ‘We will save this19 city,’ he pledged, ‘or all of us will die at our posts.’

One of the 62nd Army’s political commissars – the party officials attached to every regiment to root out subversion and instil discipline – was Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev had previously served as head of the Ukrainian Communist Party, distinguishing himself by the alacrity with which he purged and executed his fellow officials. He had been with the Red Army as it invaded eastern Poland and had later helped organise the defence of Kiev in 1941.

Even before the German ground forces arrived at Stalingrad, the Luftwaffe had bombed the city to the point of devastation. The port facilities on the River Volga, which the Soviets relied on for supplies, had been destroyed. One Soviet soldier, Nikolai Razuvayev, wrote in his diary:

A voice boomed20 from the loudspeakers: ‘Air-raid warning!’ and two or three minutes later the anti-aircraft guns opened up. Five minutes after that thousands of bombs began to drop. After ten minutes the sun was blocked out. The ground beneath my feet was shaking. Everything was covered in smoke and dust. There was a continuous roar from all sides, and fragments of bombs and broken stone were falling from the sky. It went on like this until darkness fell. The city was in flames. And with dawn, the air raids resumed.

Stalin had decided not to evacuate Stalingrad, believing the troops would be less inclined to defend a deserted city. In the first two days of the bombardment 25,000 civilians were killed. Over the next six months, 2 million soldiers would battle for a city that was already in ruins. The Germans initially had more men, more tanks and more planes, but Chuikov kept his pledge. His men fought for every house and every yard of shell-holed street. The more the city was reduced to rubble, the harder it became for the invaders. Street fighting did not suit the Wehrmacht; its tanks and motorised units could not operate in the constricted space. But the Soviet forces learned quickly how to use the conditions to their advantage, splitting into small mobile units, moving rapidly from location to location, harrying the enemy. Chuikov instructed his men to ‘hug the enemy close’, always keeping the two front lines on top of each other so the Germans could not call up artillery support fire without destroying their own forces.

Stalin pressed Marshal Zhukov to mount a counteroffensive to cut off the German army around Stalingrad and in the Caucasus to the south, but Zhukov told him nothing could be done for at least two months. In the meantime, Chuikov would have to hold the city without reinforcements, as all reserves of troops, tanks and aircraft were needed for the coming offensive. By now the fighting had descended into the most brutal hand-to-hand combat. At times the Germans controlled the upper floors of a building while the Russians held the basement, battling for the floors above or below them. One German soldier wrote, ‘Stalingrad is no longer21 a city. By day it is a cloud of burning, blinding smoke. When night arrives, the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately to the other bank.fn1 Animals flee this hell. Even the hardest stones cannot bear it. Only men endure.’

Women served as messengers, signallers and as combatants on the front line. The most renowned were the regiments of ‘Night Witches’, women pilots who flew ancient Soviet biplanes under cover of darkness. The planes made little noise and their bombs fell without warning. Bridges and forward airfields were their preferred targets, terrorising the Germans with the suddenness of their attacks.

Snipers, using the rubble as cover, killed hundreds and were glorified. The young Siberian, Vasily Zaitsev, was credited with over 300 kills, his exploits widely celebrated by the Soviet propaganda machine. Mila Pavlichenko22 matched Zaitsev’s tally, and German troops dubbed her ‘the Russian Valkyrie’. They felt she decided who lived or died on the battlefield. Pavlichenko was paraded through the Soviet Union, and taken on tours of Britain and the United States. The message she relayed on behalf of the Kremlin was that the Allies should show as much courage as she had, by opening a second front in Western Europe. The author Vasily Grossman was in Stalingrad for the six months of the battle and describes it in harrowing detail in Life and Fate (1959). In one of his less known works, ‘An Everyday Stalingrad Story’ (1942), he follows a 19-year-old sniper, Anatoly Chekhov, as he plies his deadly trade:

A German carrying23 an enamel plate turned the corner. Chekhov had learned that the soldiers always came out with their pails at this time to fetch water for the officers. He turned the distance wheel, raising the crossed hairline of his sights; he shifted them 4 centimetres forward from the soldier’s nose and fired. A black spot suddenly appeared beneath the soldier’s cap, his head jerked backward, and the pail fell with a clatter from his hand. Chekhov felt a shudder of excitement. A minute later, another German appeared around the corner with a pair of field glasses in his hands. Chekhov pressed the trigger.

The world watched the battle, and the conviction grew that if Stalingrad could be held, the war could be won.

Slowly the Wehrmacht extended its hold over the city. The Soviet forces clung to the eastern suburbs and the thin strip of land between Stalingrad and the River Volga. Von Paulus had already informed Hitler that the Nazi standard was flying over Stalingrad; it only remained to force the last defenders over the river. But the Germans had not reckoned with the tenacity and self-sacrifice that had driven Russians to defend their homeland for nearly a thousand years. ‘There is no place for us behind the Volga!’ was the motto drummed into the troops. ‘Not one step back!’ was a warning as well as an exhortation – retreat over the river would be met with reprisals. The Soviets suffered24 huge numbers of casualties. The 13th Guards Division under General Alexander Rodimtsev had lost 95 per cent of its 10,000 men by the end of September. In his memoirs, Chuikov says mass military sacrifice led to victory:

At the end of the attack25 the enemy had advanced only a mile. They made their gains not because we retreated but because our men were killed faster than we could replace them. The Germans advanced only over our dead. But we prevented them from breaking through over the Volga. The Germans lost tens of thousands of dead in half a mile of soil and they couldn’t keep it up. Before they could renew their ranks with fresh reserves we launched a general offensive.

The Soviets did not retreat beyond the Volga. Perhaps the most heroic action of the campaign came with the defence of ‘Pavlov’s House’, a central apartment block fortified and defended by a force of just two dozen soldiers under the command of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov. The men had captured the four-storey building at the end of September and held out for two months against wave after wave of enemy attacks. German military dispatches referred to it as a fortress and assumed it had an endless supply of defenders. Pavlov was surprised when he was later acclaimed as a hero and showered with medals. His casual valour was very much in the tradition of War and Peace’s gunner Tushin and all the ‘little men’ whose deeds Tolstoy believed to be the driving force of history. Chuikov said that more Germans died trying to take ‘Pavlov’s House’ than had done in taking Paris. The fate of Stalingrad was decided by such deeds.

The tenacity of the defenders of Stalingrad had won Zhukov the time he needed to gather his forces, and the Soviet counteroffensive, codenamed Operation Uranus, was launched on 19 November 1942. Vasily Grossman described it as ‘two great hammers26, one to the north and one to the south, each composed of millions of tons of metal and human flesh’. Amazingly, the Red Army had managed to keep the build-up of thousands of tanks, guns and men concealed from the Germans. For once, Stalin had not hurried his commanders, and the offensive was efficiently prepared. Blinded by his desire to capture Stalingrad, Hitler had taken forces from the flanks of his army, leaving them badly weakened. Zhukov’s pincer movement took advantage. By 23 November27, some 300,000 Germans and their Romanian allies had been surrounded in a sealed enclave they christened the Kessel or ‘cauldron’. Hitler instructed the commanders of the 6th Army not to try to break out, but to dig in and wait for the Luftwaffe to fly in weapons and supplies. The decision proved disastrous. The Luftwaffe was unable to transport anything like the necessary quantities of material, and the trapped men quickly found themselves isolated and close to starvation. For the majority of them, the Christmas of 1942 would be their last. The diaries and letters of the men in the Kessel, with their talk of snow and Christmas trees and Schubert on the piano, make poignant reading as they realise they have been abandoned to their fate. Hunger and frostbite took their toll. In early January, von Paulus reported, ‘Army starving and frozen28. No ammunition. No longer able to move tanks.’ When a Luftwaffe general flew in to the Kessel to announce that supply operations were no longer possible, von Paulus told him, ‘Don’t you realise the men are so hungry that they pounce on the corpse of dead horses, split the head open and devour the brains raw!’fn2 By 2 February 194329, when they finally ignored Hitler’s threats and surrendered, only 90,000 of the initial 300,000 men remained alive. Of these just 5,000 would make it back home, having endured captivity in Soviet camps for many years after the war. The 6th Army, which had marched triumphantly through Belgium and France, was annihilated. Over a million people died in the battle for Stalingrad. But its outcome turned the war in favour of the Allies. The Soviets had ensured that the Germans would retreat from now on.

In the north the blockade of Leningrad continued. The city had been shelled remorselessly since August 1941, enduring 254 days of bombardments in 1942 alone. Its population was suffering terribly. On Nevsky Prospekt, the city’s main thoroughfare, there are still reminders of the dark times, including a sign painted on a wall. ‘Citizens!’ it reads. ‘During air raids this side of the street is more dangerous!’ The Germans were so close that their music could be heard playing over loudspeakers; announcements in Russian called on Leningraders to surrender. On the outskirts of the city, Nazi troops laid waste to the great royal palaces – Peter the Great’s summer residence at Petrodvorets, the Catherine Palace at Tsarskoe Selo and the royal estate at Gatchina. Repeated attempts to break the siege had failed, and thousands were dying of hunger every month. People ate dogs and cats; the animals disappeared from the Leningrad zoo. The bodies of those who collapsed from exhaustion were left lying in the street where they fell. Of the approximately 2.5 million residents30 at the start of the blockade, nearly 800,000 are thought to have starved to death, with 200,000 more killed by bombing raids. The physical destruction was immense. The city of Peter had been reduced to a shell of its former self. On returning to Leningrad in May 1944, Akhmatova wrote of her anguish at finding ‘a terrible, terrible ghost that pretended to be my city’.

But Leningrad had not fallen. The heroism and ‘Asiatic’ stubbornness of the Russian people had repelled the Nazi hordes. I remember as a schoolboy staying at the city’s famous Astoria Hotel (not then restored to its traditional – and expensive – splendour) and seeing some faded documents framed under glass in the hotel lobby. They were invitations from Adolf Hitler to the victory party he had confidently planned to hold in the Astoria. They had been printed in advance and even gave the date in 1942 on which the party was scheduled to take place.fn3

As the Germans were pushed back, Hitler ordered what would be his final offensive on the Eastern Front. The Soviet forces had been moving westwards at differing speeds in different sectors, and those around the city of Kursk, 300 miles south of Moscow, had advanced considerably further than the sectors immediately to their north and south. The effect was to create a bulge, or salient, of Soviet troops that Hitler decided was a vulnerable target. On 4 July 1943, some 900,000 German soldiers31 and nearly 3,000 tanks launched Operation Citadel. The aim was to attack the Kursk salient in a pincer movement from north and south and cut off the advanced Soviet forces. It was the first move in what was to be the largest tank battle in history. Zhukov had received intelligence reports of Hitler’s intentions and was able to prepare defensive positions involving a million men, 4,000 tanks and 3,000 aircraft. The battle lasted for 50 days. Never before had a German blitzkrieg offensive failed to pierce the enemy’s defensive line, but this time the Soviets stood firm. Just as at Borodino in 1812, the Russians lost more men than their foes, but the psychological victory was undoubtedly theirs. With the German advance halted, the Soviets sent penal battalions to clear the enemy minefields and thousands of T-34 tanks poured forward into the gap in the German lines. Hitler was again forced to retreat.

The Soviet victory at Kursk coincided with the American and British landing in Sicily in July 1943. The Axis Powers were now under siege from east and south, and the Allies were increasingly confident of success. In November 1943, the leaders of the big three Western Allies met for the first of their wartime conferences in Tehran. Stalin repeated his demand that Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt open a second front in Western Europe and they agreed to do so, by May 1944 at the latest. More controversial was the question of what to do with Poland after the war. Stalin was adamant that the Soviet Union should hold onto Western Ukraine, Belorussia and the territory in eastern Poland that had once belonged to ancient Rus. He argued that Poland could be compensated with land on its western border that was currently part of Germany. Churchill and Roosevelt provisionally agreed that the post-war Soviet–Polish border would be along the Curzon Line of 1919. This would give the Soviet Union most of the Polish territory it had annexed under the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, including the cities of Lvov, Brest-Litovsk and Vilnius. The Polish Government in Exile in London, officially recognised by the Allies as the country’s legitimate government, were not even consulted. Their outrage at the proposed loss of Polish land met with little sympathy.

By the summer of 1944, the Germans had been driven out of the last square mile of Soviet territory. Operation Bagration, launched two weeks after the D-Day landings in Normandy, succeeded in dislodging the Axis forces from Belorussia and eastern Poland. Fifty-seven thousand captured Germans32 were paraded through Moscow in front of jeering crowds.fn4 The Red Army swept through Romania, Hungary and Slovakia, and in early August it neared the eastern suburbs of Warsaw.

In anticipation of the approaching battle, the non-Communist Polish resistance movement, the Armia Krajowa (Home Army), loyal to the exiled government in London, staged a concerted uprising against the Nazi occupiers. The timing of the uprising, which began on 1 August, was intended to stake Poland’s claim to independence: the fighters wanted to have a hand in liberating Warsaw, to prevent Moscow claiming that it alone had rescued Poland. The Poles knew the Red Army stood on the eastern bank of the Vistula River and they expected the Soviets to join them in expelling the Germans. Indeed, Radio Moscow had been broadcasting appeals for Poland to rise up. But the Russians did nothing. For the next two months, the Red Army sat and watched as the Poles fought alone. At first the Armia Krajowa (AK), supported by the city’s civilian population, enjoyed a measure of success, gaining control of large areas. But their forces were limited and inadequately armed. In mid August, the tide turned: the Germans had regrouped and were inflicting serious damage on the Poles. On instructions from Heinrich Himmler, the SS declared all inhabitants of the city to be legitimate military targets and went from house to house shooting men, women and children. Up to 50,000 civilians were executed by the Nazis and many more died in bombardments and exchanges of fire. The AK appealed for help, but Moscow did not respond. Churchill pleaded with Stalin to help the Poles, but he refused. By early September, the uprising was doomed. The partisans tried to escape through Warsaw’s sewers, but many of them were rounded up and shot.fn5 After the surrender of the remaining resistance forces, the Nazis decided to punish the Poles by systematically destroying their city. When the Soviets finally arrived in January 1945, around 85 per cent of the capital lay in ruins, making Warsaw the most damaged city in the war. A poem by a young Polish partisan, Jozef Szczepanski, was discovered in the ruins, with a defiant message for the Russians who had left him and his colleagues to die:

Know this! You cannot harm us33!

You can choose to help us, deliver us,

Or still delay and leave us to perish …

Death is not terrible; we know how to die.

But know this! From our tombstones

A new Poland will be born in victory,

And never will you walk our land,

You Red ruler of bestial forces!

Sadly, Szczepanski was wrong. By deliberately postponing the seizure of Warsaw, Stalin had allowed the leading representatives of Polish nationalism to be wiped out en masse. The AK’s rival, the much smaller Communist resistance group, the Armia Ludowa (People’s Army), had been instructed by Moscow not to take part in the uprising, and its forces had survived intact. At Stalin’s insistence, they would now provide the country’s post-war pro-Soviet government, laying the foundations of the Communist yoke that would weigh on Poland for the next four decades.

After Warsaw, the Red Army resumed its rapid advance. By February 1945, it was34 within 50 miles of Berlin and facing desperate resistance from German forces. In the final months of the war, an astounding 300,000 Soviet soldiers were killed and over a million wounded on German soil. The Soviets were bent on revenge for the Nazi atrocities carried out in the Soviet Union. There was widespread rape, looting and the killing of civilians. Soviet commanders intervened only sparingly and only when such activities jeopardised discipline. Stalin himself was aware that Red Army soldiers raped tens of thousands of German women and tried to justify it in a conversation with the Yugoslav leader, Josip Tito, in April 1945:

I take it you have read Dostoevsky35? So you know how complicated a thing the human psyche is? Well, imagine a man who has fought from Stalingrad to Belgrade, over thousands of kilometres of his own devastated land, across the dead bodies of his comrades and dear ones. How can you expect such a man to react normally? And, anyway, what is so awful in him having a bit of fun with a woman after such horrors? The Red Army is not composed of saints, nor can it be … The important thing is that it fights Germans.

The author Ilya Ehrenburg, who together with Vasily Grossman was among the greatest Soviet war correspondents, had spent the preceding years documenting German atrocities. Writing in the Red Army newspaper, Red Star, he had a stark message of revenge:

The Germans are not human36 … If you have killed one German, kill another. There is nothing better than German corpses. Don’t count the miles you have travelled; count the number of Germans you have killed. Kill a German – that is what your mother asks of you. Kill a German – that is what your child begs of you. Kill a German – the earth that bore you is crying out for you to do it. Don’t miss. Don’t hesitate. Kill.

Ehrenburg, like Grossman, was Jewish and the two of them undertook a project to detail the Nazis’ crimes against Soviet Jews. Their ‘Black Book of the Holocaust’ in the USSR bears exhaustive witness to the massacres and persecution, but for many years it remained unpublished. The Soviet authorities’ ambivalent attitude towards anti-Semitism, and their unwillingness to ‘divert attention from the suffering of the Soviet people’, led them to ban it. From January 1945, the Red Army began to liberate the Nazi concentration camps in Central Europe: Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Sobibor and Treblinka. Vasily Grossman’s article ‘The Hell of Treblinka’ (1944), for which he interviewed survivors and local inhabitants, would be used as evidence that helped convict the men responsible at the Nuremburg Trials.

With Soviet troops approaching Berlin, the Allies met again. This time, at Stalin’s insistence, the conference was held at the Black Sea resort of Yalta, on 4 February 1945. It was here that the fate of Europe would be finally decided, and the foundations laid for the division between East and West that would last almost half a century. Roosevelt was by now a sick man, with only two months left to live. The newsreel footage of the Yalta conference shows him looking drawn and weak, barely able to lift his arm to shake hands with the other participants. Stalin took advantage, bullying FDR into accepting his vision of Europe’s future, freezing out Churchill whenever he objected. It was agreed that the Polish Government in Exile would return from London to join the Communist-dominated Provisional Government already installed in Warsaw. Stalin accepted that elections would be held as soon as possible, secure in the knowledge that pro-Communist forces were already in charge. Together with the confirmation that the Curzon Line would be recognised as the border between Poland and the Soviet Union, the measures were a sell-out of Polish interests. Even today, Poles regard ‘Yalta’ as a synonym for treachery and double dealing.

In mid April, the final assault on Berlin began. The forces of Marshals Zhukov and Konev raced each other to take the prize, pounding the Nazi capital37 with ceaseless artillery barrages, firing a greater tonnage of ordnance than the Allied bombers had dropped on the city in the whole course of the war. After a week of street-to-street fighting, the Soviets arrived in central Berlin on 2 May. Hitler had committed suicide two days earlier in his bunker under the Reich Chancellery. The troops who discovered his charred corpse – together with those of Eva Braun, Josef Goebbels and his family – reportedly destroyed the evidence to prevent the relics becoming a focus for Nazi sympathisers. The famous photo38 of Soviet soldiers raising the Communist flag with the hammer and sickle over the Reichstag was taken that same afternoon, a re-enactment of the scene that had taken place the night before, when no camera had been on hand. Even the staged photo did not entirely please the Soviet censors. One of the two soldiers could clearly be seen wearing two watches, a sure sign that he had been looting. The watches were edited out before the picture was released to the world.

In the early hours of 8 May, Germany signed an unconditional surrender to the Western Allies. Stalin toasted the victory at a reception of Red Army commanders at the Kremlin:

Comrades, I would39 like to raise a toast to the health of our Soviet people and, most of all, to the Russian people. [Loud, continuous applause; shouts of ‘Hooray!’] I drink, most of all, to the health of the Russian people because they are the most outstanding nation of all the nations of the Soviet Union … the leading force among all the peoples of our country.

On 24 June, four years and two days after the Nazis had poured across the Soviet border, Zhukov led the victory parade on a white stallion across Red Square. The drama of the galloping horse and the deafening shouts of Oorah! – ‘hooray’ – were a magnificent spectacle, full of joy for the survivors, redolent with the pain of the bereaved. (Stalin had been40 determined to lead the parade himself, but had twice been thrown by the stallion and cursed, ‘Fuck this. Let Zhukov do it!’) As the Red Army troops marched past the Lenin mausoleum, throwing down the piles of Nazi standards and banners captured from the foe, the Soviet Union celebrated its greatest moment of triumph.

The nation had shown its heroism and now it hoped for its reward. As in 1812, the Russian people waited for the state to recognise their sacrifice by granting them freedom and the right to participate in the running of their country. But their aspirations for civic participation after the war were again to be thwarted. Stalin intended to return to his old methods.

fn1 The dogs had good reason to flee, as the Germans had orders to shoot them on sight. The Soviets had trained Alsatians to seek out food from under vehicles, and dispatched them with explosives on their backs to detonate under German tanks.

fn2 After the defeat at Stalingrad, Hitler urged von Paulus to commit suicide, but he refused. During his time as a prisoner of the Soviets, he became a strident critic of the Nazis and was finally released in 1953.

fn3 When I visited the hotel again more recently, I was told Hitler’s party invitations had been removed after complaints by German guests. They can now be seen in the State Memorial Museum of the Siege of Leningrad.

fn4 For many years after the war, these men would remain in the USSR, working on construction projects and other public works to ‘expiate their crimes’. The few who survived did not return to Germany until 1955. The building that used to house the BBC office in Moscow had been built by German POWs, and I remember Russians being envious of its high quality. Apartments built by ‘the Germans’ were considerably more desirable than Soviet-built blocks.

fn5 Andrzej Wajda’s 1956 film Kanal (Sewer) is a chilling reconstruction of the uprising’s last days. In Communist-ruled Poland, Wajda could not tell the full story of the Soviet treachery, but his film did enough for Poles to feel their sacrifice had not been forgotten.