Chapter 13. Dipping Our Toes, Very Tentatively, into JavaScript

If the Good Lord had wanted us to enjoy ourselves, he wouldn’t have granted us his precious gift of relentless misery.

— John Calvin (as portrayed in Calvin and the Chipmunks)

Our new validation logic is good, but wouldn’t it be nice if the error messages disappeared once the user started fixing the problem? For that we’d need a teeny-tiny bit of JavaScript.

We are utterly spoiled by programming every day in such a joyful language as Python. JavaScript is our punishment. So let’s dip our toes in, very gingerly.

Warning

I’m going to assume you know the basics of JavaScript syntax. If you haven’t read JavaScript: The Good Parts, go and get yourself a copy right away! It’s not a very long book.

Starting with an FT

Let’s add a new functional test to the ItemValidationTest class:

functional_tests/test_list_item_validation.py (ch14l001).

deftest_error_messages_are_cleared_on_input(self):# Edith starts a new list in a way that causes a validation error:self.browser.get(self.server_url)self.get_item_input_box().send_keys('\n')error=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.has-error')self.assertTrue(error.is_displayed())#

# She starts typing in the input box to clear the errorself.get_item_input_box().send_keys('a')# She is pleased to see that the error message disappearserror=self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.has-error')self.assertFalse(error.is_displayed())#

That fails appropriately, but before we move on: three strikes and refactor! We’ve got several places where we find the error element using CSS. Let’s move it to a helper function:

functional_tests/test_list_item_validation.py (ch14l002).

defget_error_element(self):returnself.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.has-error')

Tip

I like to keep helper functions in the FT class that’s using them, and only promote them to the base class when they’re actually needed elsewhere. It stops the base class from getting too cluttered. YAGNI.

And we then make five replacements in test_list_item_validation, like this one for example:

functional_tests/test_list_item_validation.py (ch14l003).

# She is pleased to see that the error message disappearserror=self.get_error_element()self.assertFalse(error.is_displayed())

We have an expected failure:

$ python3 manage.py test functional_tests.test_list_item_validation

[...]

self.assertFalse(error.is_displayed())

AssertionError: True is not falseAnd we can commit this as the first cut of our FT.

Setting Up a Basic JavaScript Test Runner

Choosing your testing tools in the Python and Django world is fairly

straightforward. The standard library unittest module is perfectly

adequate, and the Django test runner also makes a good default choice.

There are some alternatives out there—nose

is popular, and I’ve personally found pytest to be very

impressive. But there is a clear default option, and it’s just

fine.[18]

Not so in the JavaScript world! We use YUI at work, but I thought I’d go out and see whether there were any new tools out there. I was overwhelmed with options—jsUnit, Qunit, Mocha, Chutzpah, Karma, Testacular, Jasmine, and many more. And it doesn’t end there either: as I had almost settled on one of them, Mocha,[19] I find out that I now need to choose an assertion framework and a reporter, and maybe a mocking library, and it never ends!

In the end I decided we should use QUnit because it’s simple, and it works well with jQuery.

Make a directory called tests inside lists/static, and download the Qunit JavaScript and CSS files into it, stripping out version numbers if necessary (I got version 1.12). We’ll also put a file called tests.html in there:

$ tree lists/static/tests/

lists/static/tests/

├── qunit.css

├── qunit.js

└── tests.htmlThe boilerplate for a QUnit HTML file looks like this, including a smoke test:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<!DOCTYPE html><html><head><metacharset="utf-8"><title>Javascript tests</title><linkrel="stylesheet"href="qunit.css"></head><body><divid="qunit"></div><divid="qunit-fixture"></div><scriptsrc="qunit.js"></script><script>/*global $, test, equal */test("smoke test",function(){equal(1,1,"Maths works!");});</script></body></html>

Dissecting that, the important things to pick up are the fact that we pull

in qunit.js using the first <script> tag, and then use the second one

to write the main body of tests.

Note

Are you wondering about the /*global comment? I’m using a tool called

jslint, which is a syntax-checker for Javascript that’s integrated into my

editor. The comment tells it what global variables are expected—it’s not

important to the code, so don’t worry about it, but I would recommend taking

a look at Javascript linters like jslint or jshint when you get a moment.

They can be very useful for avoiding JavaScript “gotchas”.

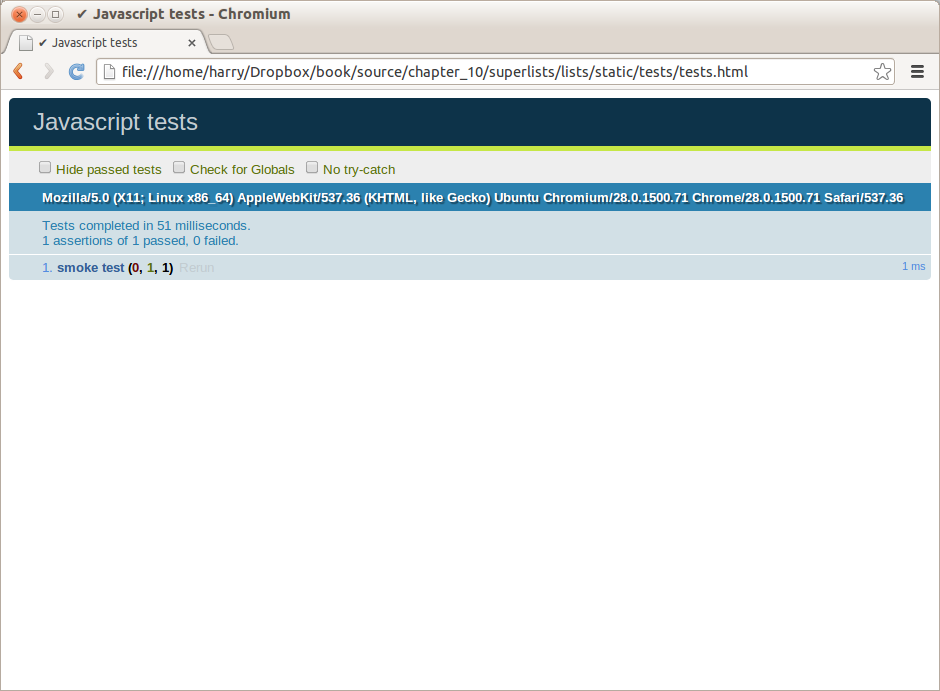

If you open up the file using your web browser (no need to run the dev server, just find the file on disk) you should see something like Figure 13-1.

Looking at the test itself, we’ll find many similarities with the Python tests we’ve been writing so far:

test("smoke test",function(){//

equal(1,1,"Maths works!");//

});

The

testfunction defines a test case, a bit likedef test_something(self)did in Python. Its first argument is a name for the test, and the second is a function for the body of the test.

The

equalfunction is an assertion; very much likeassertEqual, it compares two arguments. Unlike in Python, though, the message is displayed both for failures and for passes, so it should be phrased as a positive rather than a negative.

Why not try changing those arguments to see a deliberate failure?

Using jQuery and the Fixtures Div

Let’s get a bit more comfortable with what our testing framework can do, and start using a bit of jQuery

Note

If you’ve never seen jQuery before, I’m going to try and explain it as we go, just enough so that you won’t be totally lost; but this isn’t a jQuery tutorial. You may find it helpful to spend an hour or two investigating jQuery at some point during this chapter.

Let’s add jQuery to our scripts, and a few elements to use in our tests:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<divid="qunit-fixture"></div><form>

<inputname="text"/><divclass="has-error">Error text</div></form><scriptsrc="http://code.jquery.com/jquery.min.js"></script><scriptsrc="qunit.js"></script><script>/*global $, test, equal */ test("smoke test", function () { equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'), true); //$('.has-error').hide(); //

equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'), false); //

});

</script>

The

<form>and its contents are there to represent what will be on the real list page.

jQuery magic starts here!

$is the jQuery Swiss Army knife. It’s used to find bits of the DOM. Its first argument is a CSS selector; here, we’re telling it to find all elements that have the class “error”. It returns an object that represents one or more DOM elements. That, in turn, has various useful methods that allow us to manipulate or find out about those elements.

One of which is

.is, which can tell us whether an element matches a particular CSS property. Here we use:visibleto check whether the element is displayed or hidden.

We then use jQuery’s

.hide()method to hide the div. Behind the scenes, it dynamically sets astyle="display: none"on the element.

And finally we check that it’s worked, with a second

equalassertion.

If you refresh the browser, you should see that all passes:

Expected results from QUnit in the browser.

2 assertions of 2 passed, 0 failed. 1. smoke test (0, 2, 2)

Time to see how fixtures work. Let’s just dupe up this test:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<script>/*global $, test, equal */test("smoke test",function(){equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'),true);$('.has-error').hide();equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'),false);});test("smoke test 2",function(){equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'),true);$('.has-error').hide();equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'),false);});</script>

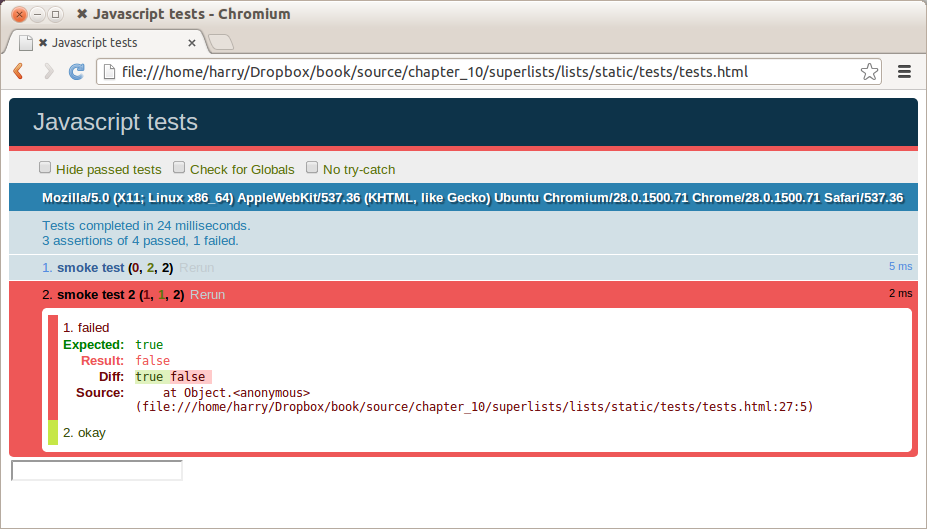

Slightly unexpectedly, we find one of them fails—see Figure 13-2.

What’s happening here is that the first test hides the error div, so when the second test runs, it starts out invisible.

Note

QUnit tests do not run in a predictable order, so you can’t rely on the first test running before the second one.

We need some way of tidying up between tests, a bit like setUp and

tearDown, or like the Django test runner would reset the database between

each test. The qunit-fixture div is what we’re looking for. Move the form

in there:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<divid="qunit"></div><divid="qunit-fixture"><form><inputname="text"/><divclass="has-error">Error text</div></form></div><scriptsrc="http://code.jquery.com/jquery.min.js"></script>

As you’ve probably guessed, jQuery resets the content of the fixtures div before each test, so that gets us back to two neatly passing tests:

4 assertions of 4 passed, 0 failed. 1. smoke test (0, 2, 2) 2. smoke test 2 (0, 2, 2)

Building a JavaScript Unit Test for Our Desired Functionality

Now that we’re acquainted with our JavaScript testing tools, we can switch back to just one test, and start to write the real thing:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<script>/*global $, test, equal */ test("errors should be hidden on keypress", function () { $('input').trigger('keypress'); //equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'), false); });

</script>

Note

jQuery is hiding a lot of complexity behind the scenes here. Check out Quirksmode.org for a view on the hideous nest of differences between the different browsers’ interpretation of events. The reason that jQuery is so popular is that it just makes all this stuff go away.

And that gives us:

0 assertions of 1 passed, 1 failed.

1. errors should be hidden on keypress (1, 0, 1)

1. failed

Expected: false

Result: trueLet’s say we want to keep our code in a standalone JavaScript file called list.js.

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

<scriptsrc="qunit.js"></script><scriptsrc="../list.js"></script><script>

Here’s the minimal code to get that test to pass:

lists/static/list.js.

$('.has-error').hide();

It has an obvious problem. We’d better add another test:

lists/static/tests/tests.html.

test("errors should be hidden on keypress", function () {

$('input').trigger('keypress');

equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'), false);

});

test("errors not be hidden unless there is a keypress", function () {

equal($('.has-error').is(':visible'), true);

});

Now we get an expected failure:

1 assertions of 2 passed, 1 failed.

1. errors should be hidden on keypress (0, 1, 1)

2. errors not be hidden unless there is a keypress (1, 0, 1)

1. failed

Expected: true

Result: false

Diff: true false

[...]And we can make a more realistic implementation:

lists/static/list.js.

$('input').on('keypress',function(){//

$('.has-error').hide();});

That gets our unit tests to pass:

2 assertions of 2 passed, 0 failed.

Grand, so let’s pull in our script, and jQuery, on all our pages:

lists/templates/base.html (ch14l014).

</div><scriptsrc="http://code.jquery.com/jquery.min.js"></script><scriptsrc="/static/list.js"></script></body></html>

Note

It’s good practice to put your script-loads at the end of your body HTML, as it means the user doesn’t have to wait for all your JavaScript to load before they can see something on the page. It also helps to make sure most of the DOM has loaded before any scripts run.

Aaaand we run our FT:

$ python3 manage.py test functional_tests.test_list_item_validation.\

ItemValidationTest.test_error_messages_are_cleared_on_input

[...]

Ran 1 test in 3.023s

OKHooray! That’s a commit!

Javascript Testing in the TDD Cycle

You may be wondering how these JavaScript tests fit in with our “double loop” TDD cycle. The answer is that they play exactly the same role as our Python unit tests.

Note

Want a little more practice with JavaScript? See if you can get our error messages to be hidden when the user clicks inside the input element, as well as just when they type in it. You should be able to FT it too.

Columbo Says: Onload Boilerplate and Namespacing

Oh, and one last thing. Whenever you have some JavaScript that interacts

with the DOM, it’s always good to wrap it in some “onload” boilerplate code

to make sure that the page has fully loaded before it tries to do anything.

Currently it works anyway, because we’ve placed the <script> tag right at

the bottom of the page, but we shouldn’t rely on that.

The jQuery onload boilerplate is quite minimal:

lists/static/list.js.

$(document).ready(function(){$('input').on('keypress',function(){$('.has-error').hide();});});

In addition, we’re using the magic $ function from jQuery, but sometimes

other JavaScript libraries try and use that too. It’s just an alias for the

less contested name jQuery though, so here’s the standard way of getting

more fine-grained control over the namespacing:

lists/static/list.js.

jQuery(document).ready(function($){$('input').on('keypress',function(){$('.has-error').hide();});});

Read more in the jQuery .ready() docs.

We’re almost ready to move on to Part III. The last step is to deploy our new code to our servers.

A Few Things That Didn’t Make It

-

The selector

$(is way too greedy; it’s assigning a handler to every input element on the page. Try the exercise to add a click handler and you’ll realise why that’s a problem. Make it more discerning!input) - At the moment our test only checks that the JavaScript works on one page. It works because we’re including it in base.html, but if we’d only added it to home.html the tests would still pass. It’s a judgement call, but you could choose to write an extra test here.