Counterknowledge

Counterknowledge, a term coined by the U.K. journalist Damian Thompson, is misinformation packaged to look like fact and that some critical mass of people believes. A recent US president-elect, having won the electoral college, claimed to have won the popular vote as well, when there was strong and documented evidence that that was not the case. The counterknowledge was repeated. Shortly thereafter, a survey revealed that 52 percent of the president-elect’s supporters, tens of millions of people, believed this falsity. It’s not just in politics that counterknowledge propagates. Examples come from science, current affairs, celebrity gossip, and pseudo-history. Sometimes vast conspiracies are alleged, such as in the claims that the Holocaust, moon landings, and attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001, never happened. Sometimes it is the outlandish claim that a pizza parlor is a front for a child sex ring run by the former U.S. Secretary of State.

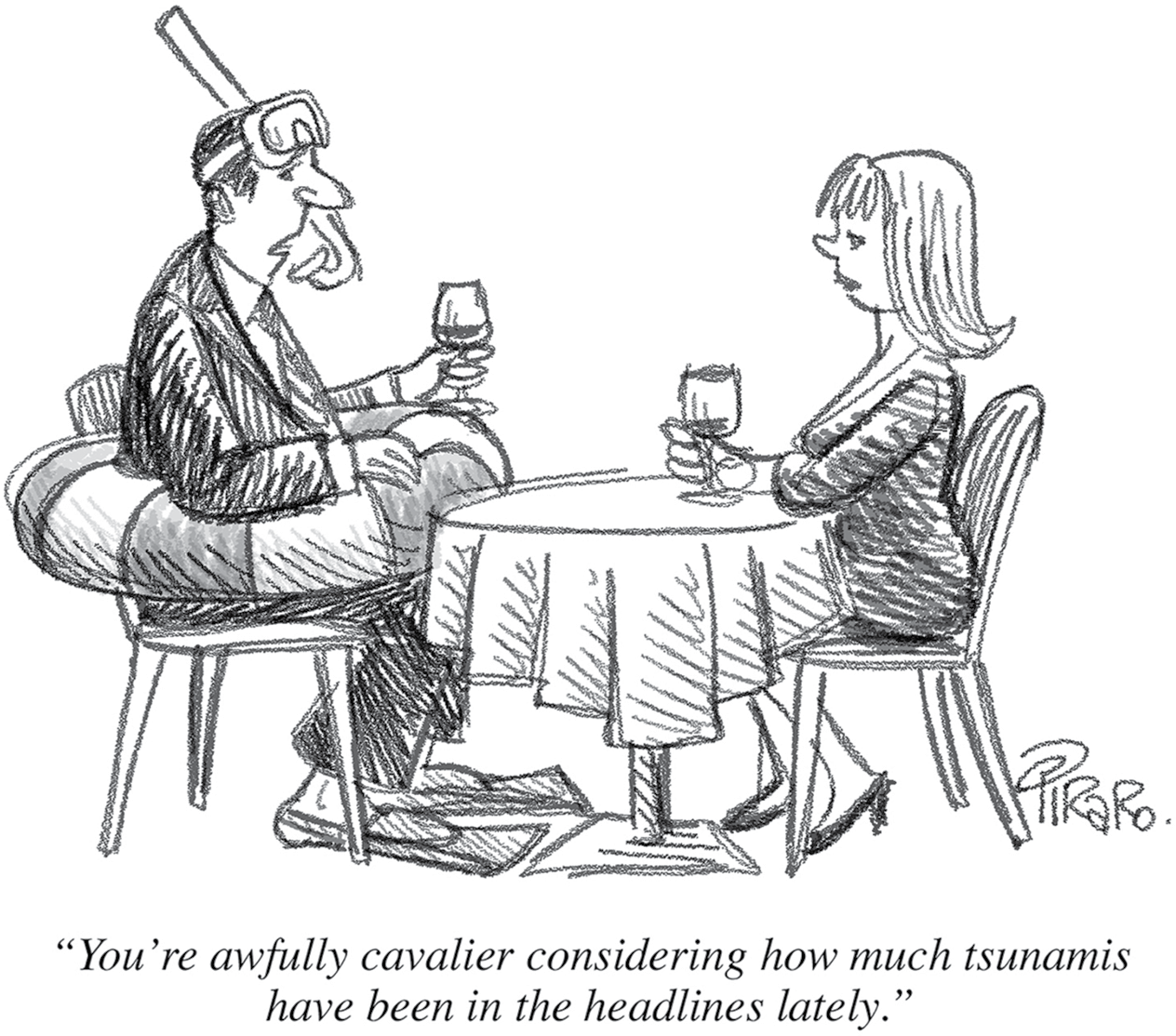

The intrigue of imagining “what if it were true” helps the fake story spread. Again, humans are a storytelling species. We love a good tale. Counterknowledge initially attracts us with the patina of knowledge and authority, but further examination shows that these have no basis in fact—the purveyors of counterknowledge are hoping you’ll be sufficiently impressed (or intimidated) by the presence of gritty assertions and numbers that you’ll blindly accept them.

Damian Thompson tells the story of how these claims can take hold, get under our skin, and cause us to doubt what we know … that is, until we apply a rational analysis. Thompson recalls the time a friend, speaking of the 9/11 attacks in the United States, “grabbed our attention with a plausible-sounding observation: ‘Look at the way the towers collapsed vertically, instead of toppling over. Jet fuel wouldn’t generate enough heat to melt steel. Only controlled explosions can do that.’ ”

The anatomy of this counterknowledge goes something like this:

The towers collapsed vertically: This is true. We’ve seen footage.

If the attack had been carried out the way they told us, you’d expect the building to topple over: This is an unstated, hidden premise. We don’t know if this is true. Just because the speaker is asserting it doesn’t make it true. This is a claim that requires verification.

Jet fuel wouldn’t generate enough heat to melt steel: We don’t know if this is true either. And it ignores the fact that other flammables—cleaning products, paint, industrial chemicals—may have existed in the building so that once a fire got going, they added to it.

If you’re not a professional structural engineer, you might find these premises plausible. But a little bit of checking reveals that professional structural engineers have found nothing mysterious about the collapse of the towers. And don’t be swayed by the opinions of pseudo-experts in tangential fields who are not experts on how buildings collapse.

It’s important to accept that in complex events, not everything is explainable, because not everything was observed or reported. In the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the Zapruder film is the only photographic evidence of the sequence of events, and it is incomplete. Shot on a consumer-grade camera, the frame rate is only 18.3 frames per second and it is low-resolution. There are many unanswered questions about the assassination, and indications that evidence was mishandled, many eyewitnesses were never questioned, and many unexplained deaths of people who claimed or were presumed to know what really happened. There may well have been a conspiracy, but the mere fact that there are unanswered questions and inconsistencies is not proof of one. An unexplained headache with blurred vision is not evidence of a rare brain tumor—it is more likely something less dramatic.

Scientists and other rational thinkers distinguish between things that we know are almost certainly true—such as photosynthesis or that the Earth revolves around the sun—and things that are probably true, such as that the 9/11 attacks were the result of hijacked airplanes, not a U.S. government plot. There are different amounts of evidence, and different kinds of evidence, weighing in on each of these topics. And a few holes in an account or a theory does not discredit it. A handful of unexplained anomalies does not discredit or undermine a well-established theory that is based on thousands of pieces of evidence. Yet these anomalies are typically at the heart of all conspiratorial thinking, Holocaust revisionism, anti-evolutionism, and 9/11 conspiracy theories. The difference between a false theory and a true theory is one of probability. Thompson dubs something counterknowledge when it runs contrary to real knowledge and has some social currency.

When Reporters Lead Us Astray

News reporters gather information about important events in two different ways. These two ways are often incompatible with each other, resulting in stories that can mislead the public if the journalists aren’t careful.

In scientific investigation mode, reporters are in a partnership with scientists—they report on scientific developments and help to translate them into a language that the public can understand, something that most scientists are not good at. The reporter reads about a study in a peer-reviewed journal or press release. By the time a study reaches peer review, usually three to five unbiased and established scientists have reviewed the study and accepted its accuracy and its conclusions. It is not usually the reporter’s job to establish the weight of scientific evidence supporting every hypothesis, auxiliary hypothesis, and conclusion; that has already been done by the scientists writing the paper.

Now the job splits off into two kinds of reporters. The serious investigative reporter, such as for the Washington Post, or the Wall Street Journal, will typically contact a handful of scientists not associated with the research to get their opinions. She will seek out opinions that go against the published report. But the vast majority of reporters consider that their work is done if they simply report on the story as it was published, translating it into simpler language.

In breaking news mode, reporters try to figure out something that’s going on in the world by gathering information from sources—witnesses to events. This can be someone who witnessed a holdup in Detroit or a bombing in Gaza or a buildup of troops in Crimea. The reporter may have a single eyewitness, or try to corroborate with a second or third. Part of the reporter’s job in these cases is to ascertain the veracity and trustworthiness of the witness. Questions such as “Did you see this yourself?” or “Where were you when this happened?” help to do so. You’d be surprised at how often the answer is no, or how often people lie, and it is only through the careful verifications of reporters that inconsistencies come to light.

So in Mode One, journalists report on scientific findings, which themselves are probably based on thousands of observations and a great amount of data. In Mode Two, journalists report on events, which are often based on the accounts of only a few eyewitnesses.

Because reporters have to work in both these modes, they sometimes confuse one for the other. They sometimes forget that the plural of anecdote is not data; that is, a bunch of stories or casual observations do not make science. Tangled in this is our expectation that newspapers should entertain us as we learn, tell us stories. And most good stories show us a chain of actions that can be related in terms of cause and effect. Risky mortgages were repackaged into AAA-rated investment products, and that led to the housing collapse of 2007. Regulators ignored the buildup of debris above the Chinese city of Shenzhen, and in 2015 it collapsed and created an avalanche that toppled thirty-three buildings. These are not scientific experiments, they are events that we try to make sense of, to make stories out of. The burden of proof for news articles and scientific articles is different, but without an explanation, even a tentative one, we don’t have much of a story. And newspapers, magazines, books—people—need stories.

This is the core reason why rumors, counterknowledge, and pseudo-facts can be so easily propagated by the media, as when Geraldo Rivera contributed to a national panic about Satanists taking over America in 1987. There have been similar media scares about alien abduction and repressed memories. As Damian Thompson notes, “For a hard-pressed news editor, anguished testimony trumps dry and possibly inconclusive statistics every time.” Absolute certainty in most news stories and scientific findings doesn’t exist. But as humans, we seek certainty. Demagogues, dictators, cults, and even some religions offer it—a false certainty—that many find irresistible.

Perception of Risk

We assume that newspaper space given to crime reporting is a measure of crime rate. Or that the amount of newspaper coverage given over to different causes of death correlates to risk. But assumptions like this are unwise. About five times more people die each year of stomach cancer than of unintentional drowning. But to take just one newspaper, the Sacramento Bee reported no stories about stomach cancer in 2014, but three on unintentional drownings. Based on news coverage, you’d think that drowning deaths were far more common than stomach-cancer deaths. Cognitive psychologist Paul Slovic showed that people dramatically overweight the relative risks of things that receive media attention. And part of the calculus for whether something receives media attention is whether or not it makes a good story. A death by drowning is more dramatic, more sudden, and perhaps more preventable than death by stomach cancer—all elements that make for a good, though tragic, tale. So drowning deaths are reported more, leading us to believe, erroneously, that they’re more common. Misunderstandings of risk can lead us to ignore or discount evidence we could use to protect ourselves.

Using this principle of misunderstood risk, unscrupulous or simply uninformed amateur statisticians with a media platform can easily bamboozle us into believing many things that are not so.

A front-page headline in the Times (U.K.) in 2015 announced that 50 percent of Britons would contract cancer in their lifetimes, up from 33 percent. This could rise to two-thirds of today’s children, posing a risk that the National Health Service will be overwhelmed by the number of cancer patients. What does that make you think? That there is a cancer epidemic on the rise? Perhaps something about our modern lifestyle with healthless junk food, radiation-emitting cell phones, carcinogenic cleaning products, and radiation coming through a hole in the ozone layer is suspect. (There goes that creative thinking I mentioned in the introduction.) Indeed, this headline could be used to promote an agenda by any number of profit-seeking stakeholders—health food companies, sunblock manufacturers, holistic medicine practitioners, and yoga instructors.

Before you panic, recognize that this figure represents all kinds of cancer, including slow-moving ones like prostate cancer, melanomas that are easily removed, etc. It doesn’t mean that everyone who contracts cancer will die. Cancer Research UK (CRUK) reports that the percentage of people beating cancer has doubled since the 1970s, thanks to early detection and improved treatment.

What the headline ignores is that, thanks to advances in medicine, people are living longer. Heart disease is better controlled than ever and deaths from respiratory diseases have decreased dramatically in the last twenty-five years. The main reason why so many people are dying of cancer is that they’re not dying of other things first. You have to die of something. This idea was contained in the same story in the Times, if you read that far (which many of us don’t; we just stop at the headline and then fret and worry). Part of what the headline statistic reflects is that cancer is an old-person’s disease, and many of us now will live long enough to get it. It is not necessarily a cause for panic. This would be analogous to saying, “Half of all cars in Argentina will suffer complete engine failure during the life the car.” Yes, of course—the car has to be put out of service for some reason. It could be a broken axle, a bad collision, a faulty transmission, or an engine failure, but it has to be something.

Persuasion by Association

If you want to snow people with counterknowledge, one effective technique is to get a whole bunch of verifiable facts right and then add only one or two that are untrue. The ones you get right will have the ring of truth to them, and those intrepid Web explorers who seek to verify them will be successful. So you just add one or two untruths to make your point and many people will haplessly go along with you. You persuade by associating bogus facts or counterknowledge with actual facts and actual knowledge.

Consider the following argument:

- Water is made up of hydrogen and oxygen.

- The molecular symbol for water is H2O.

- Our bodies are made up of more than 60 percent water.

- Human blood is 92 percent water.

- The brain is 75 percent water.

- Many locations in the world have contaminated water.

- Less than 1 percent of the world’s accessible water is drinkable.

- You can only be sure that the quality of your drinking water is high if you buy bottled water.

- Leading health researchers recommend drinking bottled water, and the majority drink bottled water themselves.

Assertions one through seven are all true. Assertion eight doesn’t follow logically, and assertion nine, well … who are the leading health researchers? And what does it mean that they drink bottled water themselves? It could be that at a party, restaurant, or on an airplane, when it is served and there are no alternatives, they’ll drink it. Or does it mean that they scrupulously avoid all other forms of water? There is a wide chasm between these two possibilities.

The fact is that bottled water is at best no safer or healthier than most tap water in developed countries, and in some cases less safe because of laxer regulations. This is based on reports by a variety of reputable sources, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Mayo Clinic, Consumer Reports, and a number of reports in peer-reviewed journals.

Of course, there are exceptions. In New York City; Montreal; Flint, Michigan; and many other older cities, the municipal water supply is carried by lead pipes and the lead can leech into the tap water and cause lead poisoning. Periodic treatment-plant problems have caused city governments to impose a temporary advisory on tap water. And when traveling in Third World countries, where regulation and sanitation standards are lower, bottled water may be the best bet. But tap-water standards in industrialized nations are among the most stringent standards in any industry—save your money and skip the plastic bottle. The argument of pseudo-scientific health advocates as typified by the above does not, er, hold water.