The History of Childhood

In the modern western world, schooling is mandatory and the curriculum prescribed by state authorities who verify its effectiveness by examinations of students, teachers, and textbooks. In antiquity, parents alone were usually responsible for their children’s upbringing. At Athens there was a little outside supervision: a boy was scrutinized at successive stages of life by his father’s tribe.1 In contrast, there was no outside surveillance of girls’ upbringing, because a modest, well-brought-up young woman was hidden from the public eye. At home with her mother and other women in the household, a girl learned the skills that she would need to use as an adult. Wearing long dresses, and playing indoors with dolls and small animals, she learned to be nurturant and to perform household tasks.

Every well-governed state that comes into existence and evolves as the result of deliberate creative acts and legislation endorses the child-rearing practices and values it needs. The educational system is part of political organization, and each role in it, including parent, teacher, and pupil, is socially constructed. Only at Sparta did the state prescribe an educational program for both boys and girls beginning in childhood. Spartans themselves, of course, undertook most of the pedagogical tasks, but they also are known to have invited a few foreigners to teach the young.2 Poets were the most revered teachers in archaic Greece. There were no travelling women poets: evidently the Spartan authorities determined that education was valuable, and there was no reason to be concerned about any inappropriate liaisons between a male teacher such as Alcman and female as well as male pupils.3 Alcman’s origin, variously said to be Lydian or slave, did not pose an insurmountable deterrent (see Appendix). The earliest datable evidence for the girls’ official program is archaic and continues through the classical period. In the Hellenistic period, the traditional system for both boys and girls was discontinued. The boys’ program (agoge) was fully revived by Cleomenes III: whether the girls’ program was also restored at this time is not indisputable, but there are some hints that they were included, perhaps voluntarily rather than under the mandate of the state. When the revolution of Cleomenes failed, the agoge continued until it was abolished by Philopoemen in 188, to be later restored in an archaizing form in the Roman period. At that time as well, state supervision of girls’ education was revived through the authority of the gynaikonomos.4

In archaic and classical Sparta, girls were raised to become the sort of mothers Sparta needed, just as boys were trained to become the kind of soldiers the state required. The boys’ program was far more arduous than the girls’. Young boys left home to learn the survival techniques and skills they would need as hoplites. Their educational program was full time and competitive, and they were frequently examined by older boys and adult authorities appointed for this purpose (Xen. Lac. Pol. 2.24.1–6, Plut. Lyc. 16, 18). The goal of the educational system devised for Spartan girls was to create mothers who would produce the best hoplites and mothers of hoplites. Because all the girls were expected to become the same kind of mothers, the educational system was uniform.5 This goal obviously did not require the full-time practice and scrutiny that was imposed upon the boys. Girls lived and ate at home with their mothers. Thus it would appear that they enjoyed some privacy and leisure denied to the boys (see below). We surmise that, compared to other Greek women, they had plenty of time to do whatever they wanted to do.

Literacy

The extent of literacy in Greece in general, and in Sparta in particular, has been much debated.6 It is generally agreed that literacy at Sparta was confined to a small elite, and lack of the ability to read and write did not hinder an ordinary citizen’s ability to participate in government.7 Paul Cartledge reports that major epigraphical sources in Sparta give the names of approximately twelve women as compared with one hundred men.8 This sex ratio, however, is not direct evidence of levels of literacy for women and men respectively; rather, it is a reflection of the fact that men performed more deeds deemed worthy of commemoration and, at least until the end of the fifth century, generally had more funds at their disposal to pay for inscriptions. For example, athletic victories generated a substantial number of inscriptions, but no woman was victorious in horse racing until the fourth century (see below).

There is no reason, however, to assume that the sex ratio among literate Spartans was as skewed as it was elsewhere in the Greek world. In a democratic polis like Athens, there were strong incentives for men to learn how to read and and write;9 since women did not participate in government, there was little reason for them to become literate, though some did. In Sparta, in contrast, the education of boys was devoted to developing military skills, leaving little time for the liberal arts. Girls, however, spent time with their mothers and older women. Furthermore, since they were married at eighteen—a substantially later age than their Athenian counterparts—they had as many years as most girls do in modern western societies to devote to their education. They could well have learned reading and writing, as well as other aspects of mousike (music, dancing, poetry) in such an all-female milieu.10 Of course, in the days when poets such as Alcman were engaged to teach choirs of young maidens, they learned from the poets.11 Though copies of the poems were probably preserved in state or private archives, the oral tradition was strong (see Appendix). Doubtless the girls committed most information to memory, and did not write it down, for surely they could not have sung and danced while dangling a papyrus roll. By repeating poems like those of Alcman at festivals, successive generations of Spartans learned both their content (including mythology, religion, courtship, and etiquette) and mousike. The repetition of this material tended to create children who thought and behaved as their parents did. Thus Spartan society remained conservative and conscious of its traditions.

The educational goals of the state and the girls’ curriculum are reflected in lyrics written by Alcman for choirs of Spartan maidens:

Alcman, Partheneion 1 PMGF

Polydeuces.

Among the dead I do not take account of Lycaethus [but] of Enarsophorus and Thebrus the fast runner . . . and the violent

(5) . . . and wearing a helmet

[Euteiches], and king Areius, and . . . outstanding of demigods

. . . the leader

. . . great, and Eurytus

(10) . . . tumult

. . . and the bravest

. . . we shall pass over . . . . Destiny and Providence, of all [gods] . . . the oldest

(15) . . . strength [rushing] without shoes.

Let no man fly to heaven

. . . [or] try to marry Aphrodite

. . . . queen, or some

. . . or a daughter of Porcus.

(20) The Graces . . . the house of Zeus

. . . with love in their eyes

god . . . to friends . . .

(25) gave gifts . . . youth destroyed . . . vain . . .

(30) went, one of them [killed] by an arrow . . . [another] by a marble millstone

. . . in the house of Hades . . . .

(35) They plotted evil deeds and suffered unforgettably. There is such a thing as vengeance from the gods, and blessed is the man who, being reasonable, weaves the web of the day without weeping.

(40) And I sing the light of Agido: I see her like the sun which Agido is now calling to shine as our witness. But the renowned choir leader does not allow me to praise or blame her [i.e.,Agido] at all.

(45) For she herself is conspicuous, as if one set among the herds a strong horse with thundering hooves, a champion from dreams in caves.

(50) Don’t you see? The mount is a Venetic: but the hair of my cousin Hagesichora blooms like pure gold;

(55) and her silvery face—why need I tell you clearly? There is Hagesichora herself; while the nearest rival in beauty to Agido will run as a Colaxian horse behind an Ibenian.

(60) For the Pleiades rise up like the Dog Star to challenge us as we bear the cloak to Orthria through the ambrosial night.

(65) There is no abundance of purple sufficient to protect us, nor our speckled serpent bracelet of solid gold, nor our Lydian cap, adornment for tender-eyed girls, nor Nanno’s hair, (70) nor Areta who looks like a goddess, nor Thylacis and Cleesithera. Nor will you go to Ainesimbrota’s and say “I wish Astaphis were mine,” and (75) “I wish Philylla would look at me, and Demareta, and lovely Vianthemis”—no, it is Hagesichora who exhausts me with love.

For Hagesichora with the pretty ankles is not here beside us. (80) She waits with Agido and commends our feast to the gods. Gods, receive it! For the accomplishment and fulfillment are up to the gods.

(85) Choir leader, I would say I myself am a girl who screeches in vain like an owl from a roof beam; but I desire to please Aotis especially, for she is the healer for us.

(90) However, because of Hagesichora girls come to lovely peace. For it is necessary to obey the trace-horse and the driver.12

(95) Of course she is not a better singer than the Sirens, for they are goddesses, and instead of their eleven, we are only ten, and children who sing. (100) But we sound like a swan on the waters of Xanthos. And she with her thick blond hair . . . .

Alcman, Partheneion 3 PMGF

Olympian Goddesses . . . about my heart . . . song and I . . . to hear the voice of . . . (5) of girls singing a beautiful song . . . . will scatter sweet sleep . . . from my eyelids and lead me to go to the contest where I will surely toss my blond hair

(10) delicate feet . . . .

(61) with limb-loosening desire, and more meltingly than sleep and death she gazes toward . . . nor is she sweet in vain. But Astymeloisa does not answer me (65) while she holds the wreath, some star falling through the gleaming sky, or a golden bough, or a soft feather (70) she crossed on long feet. The moist grace of Cinyras [i.e., perfume] sits on the maiden’s hair.

(73) Astumeloisa among a crowd, darling of the people . . . .

(75) taking . . .

I say . . . . If a silver . . . . I might see (80) if she would love me coming near, and take me by the soft hand, at once I would worship her.

But now a child, heavyhearted . . . to a child, the girl-child

(85) grace13

As we have mentioned, Sparta was the only polis where the training of girls was prescribed and supported by public authority. The spiritual and intellectual education of girls is interesting, especially since apparently boys did not receive an education superior to that of girls (in contrast to the situation at Athens). Therefore the cultural level of girls may well have been superior to that of boys, inasmuch as the latter had to devote so much attention to military training. The intensity of the training of both sexes is unparalleled in the rest of the Greek world. Competitiveness was as much a part of the cultural curriculum as of the physical program. Alcman was hired to teach maidens to perform in choruses that stressed competition among its members both as individuals and as participants in groups of rival choruses, and his poems refer to ranking and contests.14

In the early classical period, some women could read. An anecdote about the precocious Gorgo (born in 506 B.C.E.), daughter and wife of kings, suggests that she knew how to read. When Demaratus, who was in exile, sent a secret message to Sparta by writing it on a wooden tablet and covering it with wax, Gorgo told the recipients to scrape the wax off and read the message (Herod. 7.239). While it is not reported that Gorgo herself read the message when it was uncovered, she realized that there might be writing on such a tablet. Other stories about her poise and precocity also indicate that she probably could read.15 She will have acquired her skill not necessarily through formal tuition, but while in her indulgent father’s presence, listening quietly or more likely (judging from what we are told about her assertiveness and self-confidence) piping up persistently to ask questions about the texts that poets, diplomats, bureaucrats, and other literate people consulted.16 Anecdotes about Spartan mothers sending letters to their sons urging them to be brave also suggest that literacy was not unknown among women.17 Though the source of the anecdotes is late and they can not be dated or verified, considering the fact that mothers were separated from their sons who were on military service for long periods of time, the idea that they communicated by letters is not unthinkable.

Dedications by women to female divinities that bear the name of the dedicator begin in the late seventh century. This date is consistent with the spread and use of the alphabet in the Greek world. Inscriptions, however, that include dedications do not constitute incontrovertible evidence of literacy inasmuch as they were likely to have been written by craftsmen, rather than by the dedicators themselves. Nevertheless, that inscriptions commemorating the deeds of individual women are found at sanctuaries frequented by women suggests that some women could read them (see below on the Heraea). Such inscriptions are consistent with the picture given by other sources and allow us to conclude that some women, at any rate, were literate.

Doubtless there was change over time in the rate of women’s literacy and in its relationship to the literacy of men. After the Peloponnesian War, when Sparta was no longer isolated, Spartan women were probably as literate as aristocratic women elsewhere in the Greek world.18 For example, Anonymus Iamblichi, a work written some time after the Peloponnesian War in a literary Doric, reports that the Spartans thought it was fine for their children not to learn mousike and letters.19 He may, however, be referring to boys only.20 In any case, by the middle of the fourth century, Plato describes women’s curriculum as consisting of gymnastics and mousike and comments that this program leaves plenty of time for luxury, expense, and unstructured activity (Laws 806A, cf. Rep. 5.452A). He also states that in Crete and Sparta not only men, but also women, take pride in education and goes on to praise their skills in philosophical discussion (Prot.342D: paideusis). This talent is an aspect of the women’s ability to speak. Spartan women were encouraged and trained to speak in public, praising the brave, reviling cowards and bachelors (Plut. Lyc. 14.3–6). Aristotle thought it was natural for women to be silent (Pol. 1260a28–31), and almost five hundred years later Plutarch wrote: “A wife should speak only to her husband or through her husband.”21 In Athens, respectable women were encouraged not to speak. In Xenophon’s Oeconomicus (7.10), a husband describes his young wife as having been brought up “under careful supervision so that she might see and hear and speak as little as possible.” Her husband is unusual in believing that as an essential part of her education to be his partner and to supervise the household, he must first teach her how to speak (7.10).

Some Learned Women

Of course literacy is related to verbal ability, and in Greece, even among literate circles, poetry was often either sung or read aloud. According to hazy traditions, there were two female poets in Sparta. Both of them apparently worked in the archaic period, when Sappho and lesser-known women poets flourished in other parts of the Greek world. None of the work of the Spartan women poets is extant. Megalostrata is mentioned by Alcman. He describes her as “a golden-haired maiden enjoying the gift of the Muses.”22 Several Muses were involved, for in this period poets not only wrote words, but also composed musical accompaniment, and in some cases choreography. Athenaeus (13.600f) reports that Megalostrata attracted lovers because of her conversation, and that Alcman was madly in love her. Though she is not specifically identified as Spartan, she is called a “maiden,” and as we have seen, Alcman spent much time in Sparta creating poetry for unmarried girls. Furthermore, like Helen, she is blonde, and her name is suitable for a Spartan, for it means “large army.” That she had a personal flirtation with Alcman is questionable. In Greek biographical tradition, written hundreds of years after the death of the subjects, it was common to hypothesize erotic links between creative women and men, rather than grant them an independent existence or a purely intellectual relationship with men.23

There was also a tradition about Cleitagora, a woman poet whose name was used to identify a skolion (drinking song).24 The Cleitagora is mentioned in Aristophanes (Lys. 1237, Wasps 1246), and Cratinus (254 Kassel-Austin). The Lysistrata passage suggests that she was Spartan, whereas the Wasps offers the possibility that she was Thracian: the scholiast to each passage draws the obvious, and mutually opposing, conclusion. The former inference, however, is more likely to be correct for several reasons: first, in the context of the Lysistrata where the leading female characters are an Athenian and a Spartan visitor, it is more appropriate to sing a song by a Spartan woman. Hence the ambassador in Lysistrata says it not right to sing the song called the “Telamon,” but rather the “Cleitagora.”25 Furthermore, of all Greek women, Spartans alone drank wine not only at festivals, but also as part of their daily fare.26 Therefore it is natural to attribute a drinking song to a Spartan woman who probably composed it for a woman’s festival.

The archaic period also produced at least one Spartan female philosopher. Chilonis, daughter of Chilon, one of the Seven Sages, was a follower of Pythagoras.27 Iamblichus (VP 267) named seventeen or eighteen women among the 235 disciples of Pythagoras; nearly one-third of the women cited were Spartans. In contrast, only three of the 218 men were Spartans. Some of the pseudepigrapha attributed to women were in the Doric dialect, and these originated from the group of Pythagoreans around Tarentum, a Spartan colony.28 In addition to Chilonis, Iamblichus mentions Nistheadousa 29 and Cleaichma, a sister of the Spartan Autocharidas. 30 Timycha, wife of Myllias of Croton, is singled out for her courage in resisting Dionysius, tyrant of Syracuse. Dionysius (r. 396–79) had her tortured when she was six months pregnant. Rather than reveal the secrets of the Pythagoreans, she bit her tongue off.31 Cratesiclea as well was a Pythagorean who was married to Cleanor, a fellow Pythagorean.32 Their dates are not known. Unlike Chilonis, who was said to be a contemporary of Pythagoras, Cratesiclea and Cleanor may have been neo-Pythagoreans. It was natural for members of the same family, especially a married couple, to become Pythagoreans, for the philosopher ordained rules for everyday life including dietary prohibitions and the proper seasons for sexual intercourse. The idea that prescribed commandments and structure might govern even the minutiae of life in an entire community doubtless was familiar to Spartans. Moreover, Sparta enjoyed cultural ties with Samos, Pythagoras’s native land.

The interest in philosophy continued into the Hellenistic period. As we have mentioned, one of the Pythagorean women may have been a neo-Pythagorean. Stoicism also had some effect upon Spartan women, though this philosophy was directed toward men. Cleomenes III invited Sphaerus, a disciple of Cleanthes, to give lectures to the youths and ephebes. 33When the Spartan revolutions failed, Cleomenes and his family sought aid, followed by asylum in Egypt (see chap. 4). Upon embarking as a hostage for her son’s behavior, his mother Cratesicleia set an example of courageous behavior:“Let no one see us crying or doing anything unworthy of Sparta. For this is up to us alone. Our fortunes will be whatever the deity may bestow.” She was not at all afraid of death.34 Self-sacrifice, belief in a single all-powerful divinity, and courage in the face of death are all characteristics of Stoics.

Mousike

Musical performance was an essential feature of ancient religion, and Spartans were taught to sing, dance, and play musical instruments. Athenaeus (14.632f–633a) observes that the art of music was practiced more intensely in Sparta than elsewhere, for it was a pleasant relief from the self-control and austerity of everyday life. Votive figurines depict women playing various wind, string, and percussion instruments (see chap. 6). In Alcman, Partheneion 1 (97, 99), young girls display critical judgment about their own singing abilities: though they do not sing as well as the Sirens, they sing sweetly indeed. Most of the descriptions we have about women’s practice of mousike concerns their dancing. Even Aristophanes, though he could not ever have been a witness, refers to the maidens dancing on the banks of the Eurotas (Lys. 1307–10). The hyporcheme, in which the chorus sings as it dances, was performed by Spartan men and women.35 Athenaeus (14.630e) links the hyporcheme to the comic and vulgar dance called the kordax, and comments that both are funny. Spartan women also were famous for performing another undignified dance called the bibasis (Pollux 4.102,Aristoph. Lys. 82). This dance required physical prowess and coordination, for the dancer had to jump and thump her buttocks with her heels in competition for prizes. A bronze figurine that was once thought to represent a girl runner may represent a girl dancing vigorously (fig. 1).36

Fig. 1. Girl from Prizren or Dodona.

She is dressed as a runner. That she glances back, however, rather than keeping her gaze in the direction of her feet, also suggests that she is dancing. London, British Museum 208. Photo courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Physical Education

There is more evidence, both textual and archaeological, for athletics than for any other aspect of Spartan women’s lives. Furthermore, there is more evidence for the athletic activities of Spartan women alone than for the athletics of all the women in the rest of the Greek world combined.37 Clearly these activities caught the attention of writers and lead us to conclude that Spartan women’s intense involvement in such activities was probably unique in the Greek world. Moreover, although there are relatively few high-quality works of art pertaining to the lives of Spartan women in other spheres, an impressive proportion are relevant to their athletic pursuits. Some of these artifacts are extant; others are known through descriptions by Pausanias and others.

Many of the athletic activities were part of religious festivals that were held in honor of female divinities. It is difficult to separate athletics from religion: however, we will concentrate on the former in the present chapter and the latter in chapter 6.

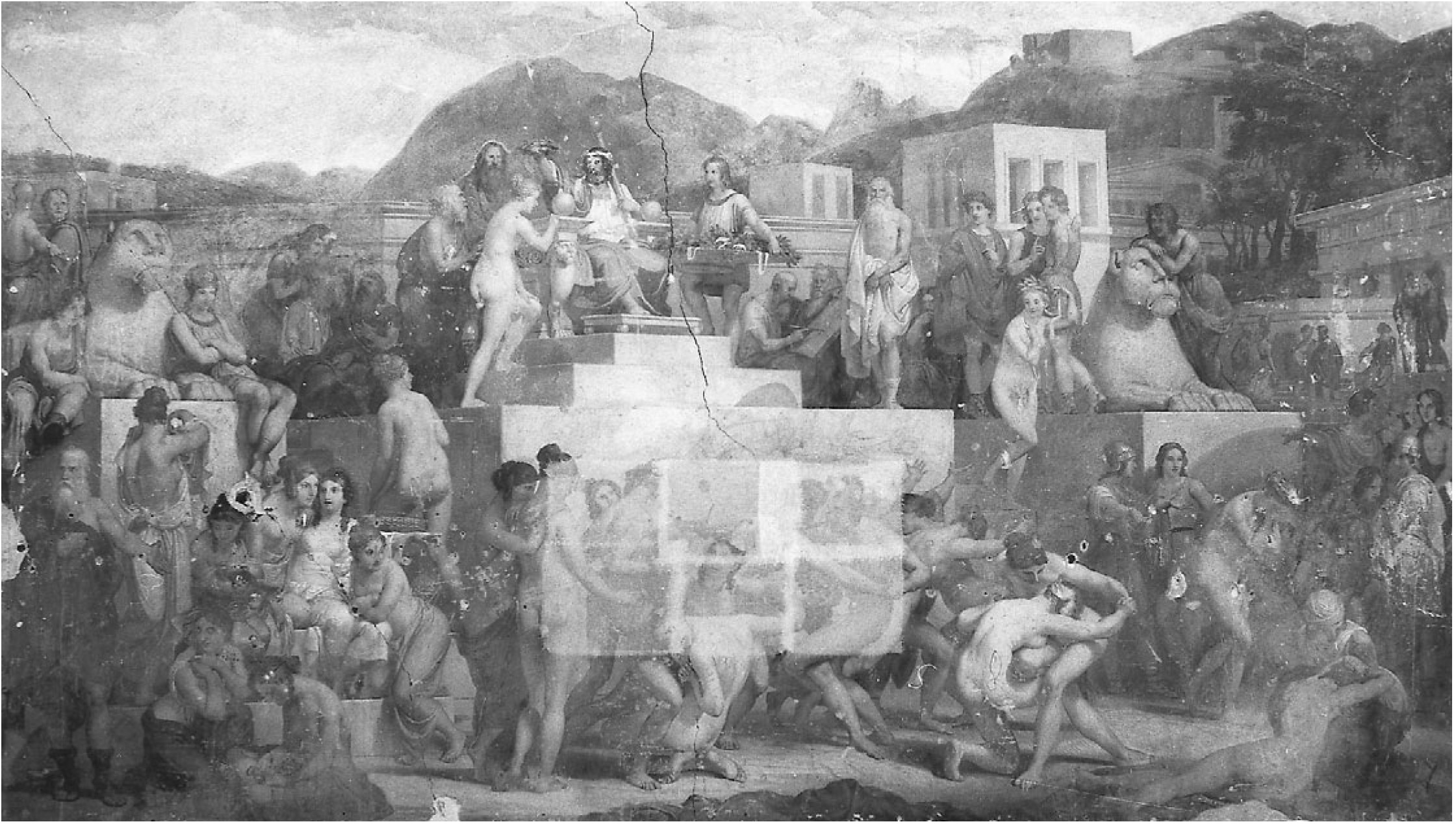

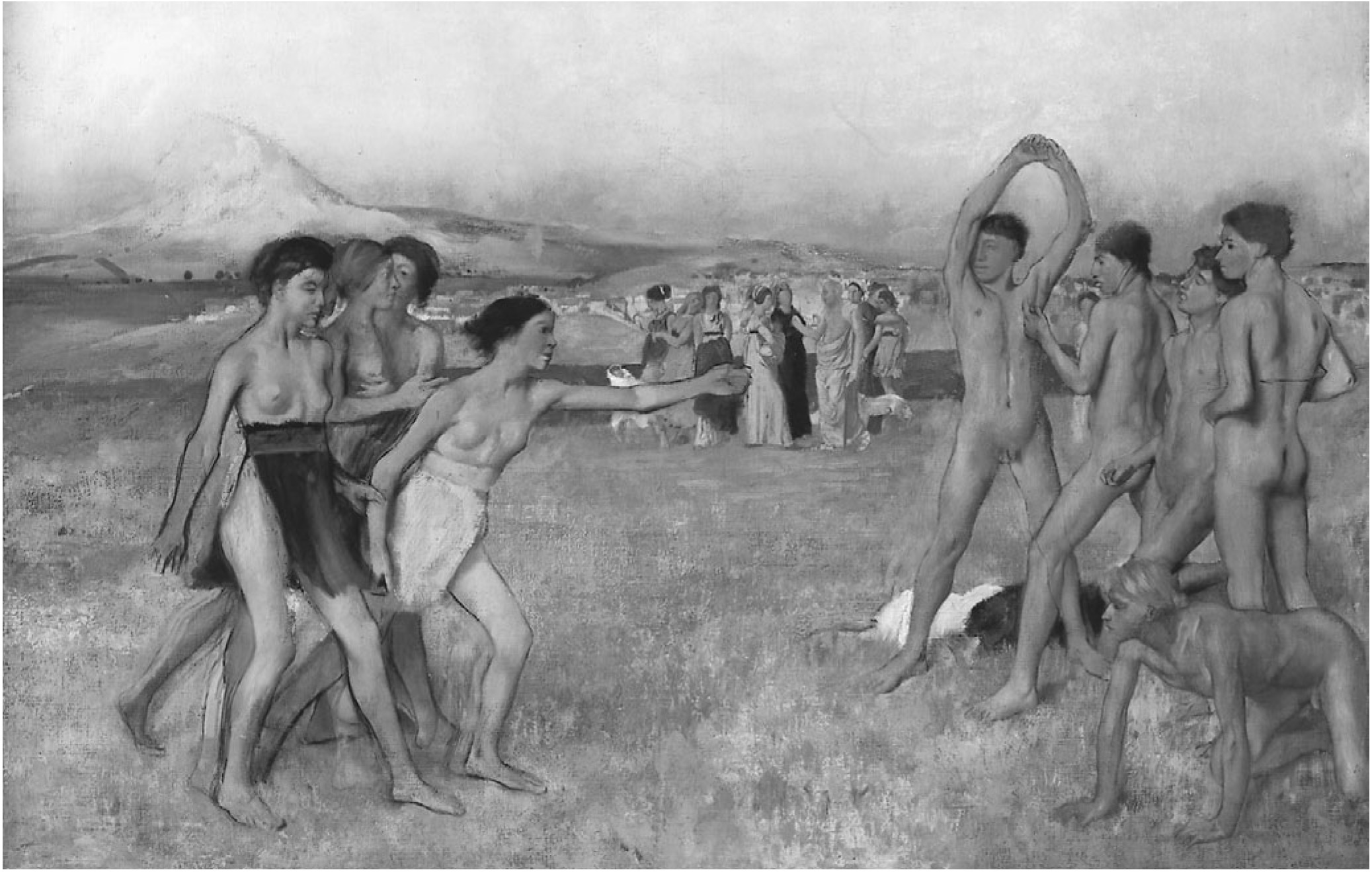

Xenophon (Lac. Pol. 1.4) states with approval that Lycurgus instituted physical training for women no less than for men, including competitions in racing and trials of strength. Euripides (Andr. 595–601) specifically alludes to racing and wrestling. Plutarch (Lyc. 14.2) gives a more explicit account of the physical curriculum, mentioning running, wrestling, discus throwing, and hurling the javelin.38 Skill in these activities is particularly useful for a soldier. The women’s curriculum was a selective and less arduous version of the men’s, but similar to it. As the girls in Theocritus announce: “we all run the same racecourse and rub ourselves with oil like men along the bathing places of the Eurotas.” 39 The silvery face mentioned in Alcman, Partheneion 1 (55), may be the glistening effect of the oil in addition to beads of sweat resulting from vigorous exercise. Since boys’and girls’ activities were similar, the question of whether they were educated together arises. In Plato’s Republic 5, male and female guardians are trained for the same jobs in the government and the military: therefore they are educated together. In proposing co-ed education, Plato’s idea is more radical than the Spartan reality of his time. Although sources agree that there was no shyness because of their nudity, it is not clear whether boys and girls used the same exercise ground and racecourse (dromos). 40 Xenophon and Plato discuss the education of boys and girls in separate sections and the agelai (“herds”) are always described as single sex.41 Given the relative strength and swiftness of men and women, co-ed competitions and trials of strength in most cases would not have been as efficient in training future hoplites as single-sex exercises. The following two nineteenth-century paintings set in the Platanistas respectively depict, first, the girls exercising separately (fig. 2), and second, provoking the boys to involve them in co-ed wrestling (fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Giovanni Demin, La lotte delle Spartane

Fresco, 1836. Villa Patt, Sedico. Photo, Zanfron.

Fig. 3. Hilaire Germain Edgar Degas, Les jeunes Spartiates (“Young Spartans Exercising”).

1860. London, National Gallery. Photo courtesy of the Trustees of

In figure 2, girls wrestle before a crowd of elders.42Members of the Council of Elders (Gerousia) stand alongside and serve as judges. Lycurgus, seated at top center, crowns a victorious girl. To his right at his feet sits a bearded old man recording the names of the victors on a tablet. Taygetus looms behind. The structure in the center is probably either the shrine of Alcon 43 or the sanctuary of Poseidon (cf. Paus. 3.14.8). The simple architecture of the monuments reflects Spartan austerity and restraint. Though the Spartan men do not leer at the girls, the modern viewer may find it difficult to distinguish between athletic and erotic nudity, and quite possibly the artist did not intend to make such a distinction. Demin may have been influenced by Roman and late Greek traditions suggesting that while exercising Spartan girls were sexually provocative.

In figure 3, note that the third figure from the left caresses the breast of the second girl from the left and kisses her.44 There is no ancient authority for the girls’ costume: to the modern viewer it resembles the apron-like skirts worn by some Native Americans. In the group behind Lycurgus stands among the mothers. Degas himself said that the rock in the background is Taygetus, from which newborns who did not pass official scrutiny were thrown.45He had studied Greek and Latin and many years after completing the picture he stated that the source was Plutarch.46 This reliance on Plutarch is doubtless a major factor in Degas’s avoidance of the potentially more licentious interpretations of Demin’s depiction.

Spartan women were not trained for actual combat; if they had engaged in co-ed athletics, they would have been more prepared. Plato (Laws 806A) and Aristotle (Pol. 1269b) complain that despite their physical education, they were no better than other Greek women when it came to defending their country.47 When the Thebans invaded Sparta under Epaminondas in 369 B.C.E., the women were terrified and panicked because their country had never before suffered invasion.48 It is necessary to point out that at that moment Spartan men were no better than other Greeks, for they had lost a battle. A century later, anticipating an attack by Pyrrhus, Archidamia, grandmother of Agis IV, rallied the other women to oppose the men’s scheme to send them to safety in Crete. They declared they had no wish to continue living if Sparta were destroyed. They performed heavy manual labor in behalf of Sparta, assisting the men in digging a trench in a single night as a defense against the elephants of Pyrrhus. 49 Finally, they told the few soldiers who were present to go to sleep and finished the trench themselves. The next day they cheered the army on. Chilonis, wife of king Cleonymus, held a rope around her neck so she would not be taken alive (see chap. 4).

One may speculate that Spartan women would have been better at defending themselves if need be, for Plutarch (Mor. 227d12) states that a goal of their physical education was to make them able to defend themselves, their children, and their country. At any rate, just as there is little evidence for illicit adultery at Sparta, there is little for the rape of individuals.50 During the bitterly fought Second Messenian War,however, Aristomenes and his troops succeeded in carrying off some maidens who were dancing in a secluded place. During the night the guards attempted to rape the maidens, but Aristomenes slew the most aggressive men, saved the girls, and released them for a large ransom.51 Spartan women were reputed to drag bachelors around the altar and to hit them to make them enter marriage at the appropriate time.52 Although the source of this gossip is a writer who tends to exaggerate, the implication is that the women were very strong, in fact powerful enough to drag around a Spartan man in his prime, not an easy job even in a ritual when the man was not resisting; and perhaps the women worked in teams.

When athletic activities were not part of ritual for women, they were purely sports. Some of the skills were useful for hunters. Xenophon (Cyn. 13.18) reports that some women enjoyed hunting. Although the women he names were the mythical Atalanta and Procris, it is possible that Spartan women engaged in this sport as well (see below). They will not have had to go far, for the region of Mount Taygetus was rich in wild game (Paus. 3.20.4–5). Doubtless, like Spartan youths, they could have outraced and encircled a hare. As we have mentioned, they were taught to throw a javelin. In that case we speculate they will have increased their consumption of protein, for meat does not otherwise appear to have been a significant part of the female diet.53 In any case, Spartan women were not anemic, and of course exercise does whet the appetite. A poet of middle comedy refers to a certain Helen who devoured a prodigious quantity of food. Helen’s name suggests that she was Spartan, or at least wanted to seem to be, and her food consumption equaled that of male athletes.54

The education of Spartans apparently affected the social construction of their religion. Plutarch exaggerates when he states that all Spartan divinities carried weapons.55 Nevertheless, at Sparta many important divinities, including Athena of the Bronze House,Aphrodite Morpho, and Aphrodite Areia, were portrayed as as warriors.56Artemis Orthia was shown wearing a helmet and holding bow and spear. In contrast, in Athens, only one major goddess, Athena, was often shown fully armed. Despite the anthropomorphism of Greek divinities, it would be naive to postulate that goddesses were invariably a direct reflection of their female worshippers. 57 For example, Athena’s helmet, shield, and spear had no implications for Athenian women, and other important gods and goddesses at Athens were not shown armed. On the other hand, the Spartan evidence, with its intense focus on martial prowess, does seem to have implications for women.58

Horsemanship

Horseback riding and chariot racing were not part of a traditional Greek physical curriculum for most boys, and certainly not for girls.59 Throughout Greece, however, wealthy gentlemen were expected to be accomplished horsemen and to be able to serve in the cavalry.60

Sparta was known for breeding and racing horses. Riding horses requires skill rather than brute strength.61 Of course, little is known about women’s education in archaic and classical poleis other than Athens and Sparta, but there can be no doubt that Sparta’s excellence in equestrian affairs had repercussions for Spartan women. Women as well as men were actively involved with horses, riding, driving horse-drawn vehicles, and engaging in competitive equestrian events. Archaeological and textual evidence from the archaic period testify to the long history of this involvement. Fragmentary terracotta figurines of Orthia riding astride and side-saddle were found at the sanctuary.62 More votives of horses than of all other animals combined were also found.63 Figurines depicting Helen on horseback similar to those found at the sanctuary of Orthia were discovered at the Menelaion. 64 Bronze votives at both sanctuaries depict female figures identified either as mortals or as Artemis and Helen riding side-saddle. The habits of divinities are not always emulated by human beings, but, as the ambivalence in the identity of the figures makes clear, there does appear to be a direct connection between goddesses and women as riders.65

In Alcman, Partheneion 1, the girls compare themselves to horses that are ridden.66 They comment that the Colaxian was inferior to the Venetic and Ibenian. 67 Because of the educational function of poetry, this remark suggests that the girls had specialized knowledge about the different strains of horses. The Colaxian was a sturdy pony, the Veneti used more for chariots than for riding, and the Ibenian perhaps Celtic or Ionian.68 They also understood chariot racing and refer to the trace-horse and the driver (line 90). At the Hyacinthia, Spartan girls drove expensively decorated light carts, and had an opportunity to display their equestrian skills before the entire community. Some raced in chariots drawn by a yoke of horses.69 For some processions, the girls rode in carriages shaped like griffins or goat-stags.70 These Spartan girls apparently had much more fun than Nausicaa described in the Odyssey (6.37–38, 57–58, etc.), who had to beg permission from her father to drive a team of two mules while riding in a cart loaded with other women and sacks of dirty laundry.

Not only could Spartan women drive horses, but they also knew how to ride them. Agesilaus II used to like to play “pony on a stick” with his young children, Archidamus, Eupolia, and Prolyta (Plut. Ages. 25.6, Sayings of Spartans 213.70). This report indicates that girls played at riding astride, and that the hobby horse on a stick was not considered a “boys’ toy.” In 220/219, at the end of the reign of Cleomenes III, the heroic wife of Panteus fled to the coast on a galloping horse.71 Thence she embarked to join her husband who was in exile with Cleomenes in Alexandria (Plut. Cleom. 38). Like male landowners, Spartan women could drive or ride out to survey their property as men did.72 Driving horses or riding them endowed Spartan women with an autonomy that was unique for women in the Greek world.

At Athens, in contrast, sumptuary laws and measures intended to curtail women’s visibility in public proscribed women’s opportunities to ride in carriages, and there is no evidence that they ever rode horses.73 Women are rarely portrayed in art riding in carriages except in marriage processions. Sometimes, of course, it was necessary to travel for a funeral or a festival. According to traditional laws ascribed to Solon, they were not to travel at night except in a wagon with a torch shining in front (Plut. Sol. 21.4) At Rome, where much more wealth was available, the Lex Oppia, enacted as a sumptuary measure in 216 B.C.E., also forbade women from riding in chariots except for religious purposes.74

That a Spartan was the first female star in Greek athletics not surprising. Cynisca was a daughter of the Eurypontid king Archelaus II and sister of two kings, Agis II and Agesilaus. Her name, Cynisca, is unusual and may be a nickname for an especially tomboyish woman. Her paternal grandfather, Zeuxidemus, was also nicknamed Cyniscus (Herod.6.71). The meaning “little hound” perhaps alludes to an interest in hunting.75 The name of her mother and of her niece Eupolia (“well horsed”),76 her sister’s name Proauga (“flash of lightning”), and her niece’s Prolyta (“she who is let loose in the forefront”) allude to equestrian interests in the female line. Cynisca is the first woman whose horses were victorious at Olympia. She must have been close to fifty years old at the time.77 The Eleans had banned the Spartans from Olympia in 420 (Thuc. 5.49–50). After the Peloponnesian War, Sparta attacked Elis, and Agis was able to offer sacrifices at Olympia in 397 (Xen. Hell. 3.2.21–31). Cynisca entered her horses at the earliest possible moment and won her victories in two successive Olympiads, in 396 and 392. No wonder Pausanias (3.8.2) calls her ambitious. Cynisca must have been champing at the bit herself for several years, hoping she would have an opportunity to race her horses at Olympia before she died.

Cynisca’s quadriga (four-horse chariot) was evidence of great wealth like that of some of her contemporaries who were victors, including tyrants in Sicily. Likewise Cynisca’s commemorative monuments were examples of conspicuous consumption equal to those of men.78 Like wealthy men who owned racehorses, Cynisca did not drive them herself but employed a jockey. Indeed, she would not even have been present at the victorious event inasmuch as women were not permitted to attend the games.79 Her image, however, stood in the sanctuary. Apelleas, son of Callicles, of Megara, created a sculpture of her chariot, charioteer, and horses in bronze, and a statue of Cynisca herself.80He also made bronzes of her horses that were smaller than lifesize (Paus. 5.12.5). These were erected at Olympia. They were the first monuments dedicated by a woman to commemorate victories at pan-Hellenic competitions. The choice of Apelleas suggests that Cynisca had done some research to find a sculptor from an allied city who specialized in images of women. Apelleas was fond of depicting women praying.81 Thus it is quite possible that Cynisca was portrayed expressing gratitude to the gods. The author of the epigram inscribed on the base of her statue is unknown. The poem is metrically competent; straightforward in the “Laconic” style; and of course written in the Doric dialect.

Cynisca herself is represented as speaking:

My ancestors and brothers were kings of Sparta.

I, Cynisca, victorious with a chariot of swift-footed horses,

erected this statue. I declare that I am the only woman

in all of Greece to have won this crown.82

This epigram was only the second ever composed to commemorate a deed of the Spartan royalty (Paus. 3.8.2). The first one was written by Simonides and was inscribed at Delphi in honor of Pausanias, victor over the Persians at Plataea. Obviously Cynisca was thought of in very exalted company. She had won the most prestigious horserace twice at the most prestigious pan-Hellenic atheletic festival. Cynisca’s commemorative sculptures at Elis stood between that of Troilus of Elis 83 and those of male Lacedemonians. Pausanias (6.2.1) includes Cynisca in his observation that after the Persian war, the Lacedaemonians were the keenest breeders of horses. No husband or children are recorded for Cynisca. 84 Xenophon and Plutarch, however, draw attention to her relationship with her brother the king, who had encouraged her to enter a chariot at Olympia in order to demonstrate that such victories were the result of wealth and expenditure, not of virtue (andragathia, “manly virtue”).85 Whether Agesilaus was actually inspired by mean-spiritedeness and sibling rivalry, or by the lofty motives Xenophon and Plutarch ascribe to him, the anecdote suggests that he thought his sister’s horses had a good chance to win. Like some male owners of victorious racehorses,86Cynisca was not only extremely wealthy, but she was also an expert in equestrian matters. According to Pausanias (3.8.2), she had an ambition to be victorious at Olympia, and was the first woman to breed horses. With the increase in private wealth, much of it in the hands of women, and with their keen interest in athletics and knowledge of horses, it was natural that Spartan women would own racehorses. Cynisca was a member of the first group of extremely wealthy women who begin to become evident after the Peloponnesian War (see chap. 4).

A heroön was erected to Cynisca near the Platanistas where the athletic contests of young Spartans were staged. In Greece it was not uncommon to treat athletes as heroes, but Cynisca was the first woman to be elevated to this status. Her shrine was in the vicinity of the shrines of mythical heroes including the sons of Hippocoön. The heroön would have been built after her death and would have served as an inspiration to other women.87

Cynisca’s example was soon followed by other women, especially Spartans; the author Pausanias (8.1) sees their victories as a trend. Among them was the Spartan Euryleonis, who was victorious at Olympia with a two-horse chariot in 368.88 A statue of Euryleonis stood with those of other luminaries such as the general Pausanias in the vicinity of the Bronze House (Paus. 3.8.1, 3.17.6). In fact the Spartans Cynisca and Euryleonis were the first women whose chariots were victorious at Olympia. Approximately a century later they were followed by royal women and women connected with the courts of Alexander’s successors (see below).89

Competitions

Competitive racing and trials of strength for women, no less than for men, were part of the physical education system instituted by Lycurgus (Xen. Lac. Pol. 1.3–4, cf. Arist.Pol. 1269b). Some of these contests were doubtless organized in a routine manner; but others took place as part of religious festivals. We are better informed about the latter.

Running races were the only athletic events for women that took place at festivals. There were races in honor of Helen,90 Dionysus,91 Hera,92 and in honor of local deities called Driodones. 93 Theocritus reports in his Epithalamium to Helen (18.22–25) that 240 maidens rubbed their nude bodies with oil as men did and raced along the Eurotas. That the girls were said to be as old as Helen when she married Menelaus indicates that the races were associated with puberty. As Theocritus reports the event, there was a tacit beauty competition as well, with Helen winning the prize (see Conclusion). The women’s race at the Heraea in Elis was the most prestigious, the equivalent for women of the Olympic competitions held for men:94

Every fourth year the Sixteen Women weave a robe for Hera, and the same women also hold games called the Heraea. The games consist of a race between virgins. The virgins are not all of the same age; but the youngest run first, the next in age run next, and the eldest virgins run last of all. They run thus: their hair hangs down, they wear a shirt that reaches to a little above the knee, the right shoulder is bare to the breast. The course assigned to them for the contest is the Olympic stadium; but the course is shortened by about a sixth of the stadium.95 The winners receive crowns of olive and a share of the cow which is sacrificed to Hera; moreover, they are allowed to dedicate statues of themselves with their names engraved on them.96

Rather than actual portraits, the statues were doubtless images of girls running with the name of the honorand inscribed.97 It is obvious that the victorious women, or their families, sought fame and immortality no less than victorious men, and were willing to pay the cost of a dedication.

Athletic Nudity

The Greek word gymnos means “nude” or “lightly dressed.”98 Nudity at Sparta may be explained in terms of religion, initiatory rites, erotic stimulation, and the requirements of athletic prowess. Though these strands are intertwined, for heuristic purposes we will separate them, and treat nudity as a costume for sports here. (For other implications, see chap. 2 and Conclusion.)

Not only did Spartan women wear a peplos (tunic) that revealed their thighs,99 but they regularly exercised completely nude.100 Mature women and pregnant women exercised.101 Even older women exercised nude. As male athletes had discovered, light clothing or none at all is best for racing. Even nowadays (or at least before the adoption of lycra bodysuits), racers wear as little clothing as possible. Thucydides (1.6) credits the Spartans with being the first to exercise unclothed.

The girls who raced at the Heraea lowered the right shoulder of the peplos and revealed their right breast.102 This costume was peculiar to this festival. No ancient source specifies the ethnic identity of the girls who competed at Elis.103 They may have been girls from the neighborhood, or at least originally so. It seems more likely, however, that the games became pan-Hellenic, though on a smaller scale than the men’s events at Olympia.104 In view of the tendency at Athens, for example, to seclude and protect young girls and to keep their names out of the public eye, it is unlikely that Athenian maidens would have been brought to race at Elis. At Athens (and probably elsewhere in Greece), girls were devalued, and the expenses involved in travelling were considerable. Therefore, if the Heraea were pan-Hellenic, only girls who lived fairly close by would have par-ticipated. Considering the likelihood that attention was not paid to women’s athletics anywhere but Sparta, and given the historical evidence for Spartan domination of Elis in the archaic period, it is likely that the games were established along Spartan principles and that the majority of competitors and victors were Spartan. Many of the sculptures at the temple of Hera were the work of Lacedaemonian artists (Paus. 5.17.2). Finally, bronze figurines depict girl runners in short peploi baring the right breast. These figurines were manufactured in Sparta (see Appendix). As we have mentioned, the bare-breasted costume was worn only by girls who raced at the Heraea. Though some prepubescent Athenians raced nude at least once in their lives at the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron, only Spartan girls regularly wore short dresses and exercised nude. Moreover, historical sources assign the earliest foundation of racing for girls anywhere in Greece to Lycurgus. For these reasons, it is generally assumed that, at least when the political relationship between Sparta and Elis was favorable, the girls who raced at the Heraea were mostly Spartans.

Nudity for women indicates that their athletic prowess was understood to be a high priority: it certainly attracted a great deal of attention, both artistic and prurient. Ibycus and later writers described the women as “thigh-flashers” (see above). In the Andromache (595–602), written in the early years of the Peloponnesian War, Euripides mentions the bare thighs and co-ed racing and wrestling. Anonymus Iamblichi reports that Spartan girls strip for exercise.105 Plato apparently knew of the Spartan practice, for it is generally assumed that nude exercise for women in the Republic (457A) is based on the Spartan reality.

Plato refers to women who are natural athletes (Rep. 456A). He also suggests that the bodies of old women are laughable (Rep. 457B), and, indeed, retreats from nudity for adult women in the Laws (833D). In the Republic (452B), all women exercise naked, though the older ones are described as wrinkled and not good-looking. In Laws (833C), Plato prescribes nude racing only for prepubertal girls, and racing clothed for adolescents until marriage at eighteen to twenty years of age. Plato’s distinction may be reflected in the artistic portrayals of Spartan girl runners, though a modern viewer may misinterpret clues to the age of subjects in ancient art.106 Bronze mirrors and statuettes portraying girls completely nude seem to modeled on a prepubertal, slim-hipped girl. Those wearing the chiton show an adolescent with fully developed breasts. The older group may be dressed because they have already reached menarche and need to wear an undergarment to absorb menstrual blood.107

Upon marriage, girls graduated from the state-controlled educational system. Some of them, at least, still managed to stay in good physical shape. Non-Spartan authors report that adult women were physically fit. Lampito, a married woman, is in excellent condition and can touch her buttocks with her feet while jumping in the air (Aristoph. Lys. 82). Spartan women needed to be able to assume this position while dancing in certain religious rituals.108 As we have just observed, in his Republic Plato states that even mature women will exercise in the nude: this ordinance may reflect some reality at Sparta. In any case, as we have seen, some mature women continued to be interested in horses and probably rode or drove to their country estates.

Education in Hellenistic and Roman Sparta

Was there an agoge for girls, and if so, was it parallel to or imitative of the boys’ agoge? These questions are further complicated by historiographic issues surrounding the boys’ agoge. According to revisionist history, the agoge as described in great detail by Plutarch was largely a Hellenistic invention that was revived in the Roman period.109 Therefore, although Plutarch’s description has enjoyed greater popularity and influence, Xenophon’s report should be understood to be a more accurate account of the educational system of the classical period. In any case, ancient authors as well as modern scholars agree that some sort of institutionalized educational system for girls existed whenever such a system existed for boys.110

In the Hellenistic period the fortunes of Sparta declined (see chap. 4). Owning good racing teams was expensive. Nevertheless, the Panathenaic victor lists for 170 B.C.E. record the victory of a Spartan woman with a quadriga. 111 She is one of nineteen non-Athenian citizens, including seven women, whose names appear on victor lists for this period (170, 166, 162 B.C.E.). Her name, Olympio, is either prophetic of her deed or a nickname alluding to an Olympic victory not otherwise attested.

In the Roman period, because Sparta was a destination for tourists, the characteristics that made Sparta distinctive were emphasized. The athleticism of women was exaggerated. Foreigners were allowed to see what they had never before been able to witness: Spartan women engaged in athletics. There were other professional women athletes in the Roman world. Therefore, in order to attract an audience, the Spartans needed not only to be good athletes, but also to create a unique image. History and tradition were mined for publicity. Spartan athletics were authentic. The reports of Plutarch (see above) and Propertius (3.14) indicate that the curriculum for girls was firmly established and well articulated in Roman Sparta. Propertius mentions nude co-ed wrestling; ball playing; hoop rolling; the pancratium (wrestling with no holds barred); discus throwing; hunting; chariot driving; and wearing armor. Vergil (Aen. 1.314–24) also describes Spartan huntresses wearing short dresses, armed with bows and arrows, pursuing a wild boar. Ovid (Her. 16.151–52) writes of a nude Helen wrestling in the palaestra. Doubtless, like other Greeks, they continued to anoint themselves with oil. One Spartan woman in the first century B.C.E. is reported to have doused herself with so much butter that the odor made a Galatian princess ill (Plut. Mor. 1109b). The Spartan, in turn, was nauseated by the smell of the other woman’s perfume, perhaps because she maintained the traditional Spartan ban on wearing perfume.

Athletic competitions for respectable women were held under state supervision.112 A fragmentary inscription of the second century C.E. indicates that the magistrates (biduoi) in charge of ephebic competitions also supervised twelve “female followers of Dionysus.”113 These Dionysiades were virgins; eleven of them ran a foot race at a festival of Dionysus.114 Another inscription from a statue honors a woman racer who won a victory.115 These games were founded under either Tiberius or Claudius.

Wrestling for women in Sparta had a long pedigree. Furthermore, since nudity often results from wrestling and other athletic endeavors, the performances of female wrestling were doubtless piquant (see fig. 3). In the days of Nero, a Spartan woman engaged in a wrestling match at Rome with a Roman senator, M. Palfurius Sura.116 Athenaeus (13.602e) reports that Spartans displayed their girls to their guests unclothed. Athenaeus may well be exaggerating: the Greek tendency to understand the world in polarized categories may have prompted Athenaeus to interpret some nudity for specific acceptable purposes (as Plutarch understood it) into gratuitous indecent display. On the other hand, if this report is true, the practice may be understood as a shocking spectacle, in keeping with the tastes of the Roman world.

Social Construction of Sexual Behavior

Plutarch (Lyc. 18.4) reports that erotic ties between older and younger women were common. In Alcman, Parthenion 1.73, the girls mention visiting Aenesimbrota, who is probably a purveyor of love magic. She would provide drugs, spells, and magical devices to attract the object of desire.117 Hagnon of Tarsus, an Academic philosopher of the second century B.C.E., states that before marriage it was customary for Spartans to associate with virgin girls as with paidika (young boyfriends).118

Weaving

According to Xenophon (Lac. Pol. 1.1), Lycurgus wisely decided that the labor of slave women (doulai) sufficed to weave the clothing that the Spartans required. Nevertheless, doulai were not the only women in Sparta who knew how to weave. To make the point about the difference between Spartans and other Greek women, Xenophon and Plato (Laws 806A) exaggerate the Spartans’ liberation from weaving. Furthermore, weaving served as a “catch-all” term for the domestic work usually performed by Greek women. In fact, Spartan women could weave and supervise their slaves’ work, but they were not encouraged to weave endlessly, nor did their reputation depend upon it. One of the Sayings attributed to Spartan women underlines this ethnic distinction:

When an Ionian woman was proud of something she had woven (which was very valuable), a Spartan woman showed off her four well-behaved sons and said these should be the work of a noble and honorable woman, and she should swell with pride and boast of them. (Plut. Sayings of Spartan Women 241.9)

Although servile women did the routine weaving, freeborn women wove for ritual purposes. Paraphernalia for weaving and hundreds of plaques depicting textiles were discovered at the shrine of Artemis Orthia. 119 These offerings date from the archaic to the Hellenistic period, but most are probably sixth to fifth century.120 Literary testimony conplements the archaeological finds. Ten young girls in a choir for whom Alcman wrote a Partheneion (1.61) sing about bringing a cloak to Artemis Orthia. Presumably, like the Arrephoroi who began the weaving for the peplos of Athena at Athens, they had participated in making the cloak.121 Pausanias (3.16.2) reports that every year women wove a chiton for Apollo of Amyclae in a room designated as the chitona. 122

The xoanon (wooden image) of Artemis Orthia wore a polos (head-dress representing the celestial sphere) and a woven dress reaching to the feet.123 The figure must have been small and light, for the priestess held it during the whipping ceremony (Paus. 34.16.10).124 Therefore annual or quadrennial weaving of garments for the divinities could not have been a great burden to Spartan women. Furthermore, weaving garments need not have entailed the obligation to prepare the wool and the performance of messy, tedious tasks including washing, beating, combing, carding, dyeing, and spinning. Rather, like Helen who spun with her golden distaff125 (one suspects not very energetically), Spartan women were not required to expend much labor in producing clothing for their cult images. At least ten girls are named in Alcman, Partheneion 1, and they wove only one cloak. Clothing the xoanon of Artemis was like dressing a large doll.

In contrast,Athenian women not only wove for the oikos (family,household, estate), but also were responsible for weaving a peplos for Athena annually. The wooden image was probably less than lifesize, and the cloth depicted on the Panathenaic frieze around 2.0–2.5×1.8–2.3 meters.126 Every four years, however, they had much more work. The peplos woven by Athenian women for the greater Panathenaea was an elaborate tapestry, so large that it was fixed as a sail on the Panathenaic ship.127 This peplos was probably about 4–8 meters square,128 and all who attended the festival could admire or criticize the result.

Since Spartan clothing was less elaborate than Athenian, the women who wove in Sparta had less to do. Young boys wore a chiton or went nude: they were allocated only one cloak to wear throughout the year, and did not sleep on mattresses, but on straw which they gathered themselves (Plut. Lyc.16.6–7). Adult men wore a short red cloak and were buried with only such a cloak and a chaplet of olive leaves.129 Since the cloaks constituted a kind of uniform, they may have been distributed by the state. Women’s peploi were short and scanty: for racing they wore the chiton exomis (tunic with one sleeve) which barely reached the knee (Paus. 5.16.3). Unlike Athenian women, they did not normally wear many layers of clothing. They probably wore whatever the weather required (see chap. 2, fig. 4,Vix crater, and Conclusion). Such dress did not command attention; but their skimpy attire did. When the women were preparing to dig a trench against the attack of Pyrrhus, some wore outer dresses (himatia) over their tunics, and some wore only their tunics (monochitones, Plut. Pyrrh. 27.3). Dionysius, the clever tyrant of Syracuse, assumed that expensive Sicilian chitons for Lysander’s daughters would constitute an irresistible bribe. At first Lysander refused to accept them, but later on, when a Sicilian ambassador showed him two dresses and asked him to choose one for a daughter, Lysander took both, for he had more than one daughter (Plut. Lys. 2.5). Doubtless the increase in visible private property that took place after the Peloponnesian War also affected women’s wardrobes.

The brief chiton exomis worn by Spartan women caused as much consternation to other Greeks as the miniskirt. Artemis, when she was portrayed as a huntress, and the Amazons were the only other females known to the Greeks who wore such short skirts, and they were visible only in art, not in real life. Because Spartan women were in fine physical condition, their skimpy clothing must have been flattering. In contrast, respectable Athenian women exercised only by doing housework, mostly indoors or in the courtyard of their house. The visual arts portray Athenian women as heavily covered in many layers of cloth, with skirts reaching to the ankles. Even little girls wore long dresses. In the sumptuary laws attributed to Solon, it was deemed necessary to specify limits to the amount of clothing Athenian women might include in their dowries, or wear at funerals, or use to wrap the dead.130

Weaving was the only activity of women that most Greeks recognized as productive.131 In prosperous households, more fabrics than could ever be used by the household were woven. These were stored up, to be given as gifts or part of dowries, or, if times were hard, to be sold or traded at the marketplace. At Sparta, neither women nor men engaged in activities that produced objects for use or sale. In fact, such work was prohibited.

Not until the Hellenistic period were the names of the Athenian women who had woven the peplos for Athena announced. In contrast, like Greek men who had always sought fame, Spartan women had a consciousness of themselves that is conveyed to the observer. Their pride shines forth in Alcman’s poetry, in Plutarch’s Sayings of Spartan Women, and in the dedications of victors’ images at the sanctuary of Hera at Elis and of Zeus at Olympia. As girls and women, Spartans left their mark on the historical record in pan-Hellenic contexts.

1. See further Sarah B. Pomeroy, Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece (Oxford, 1997), 141–42 and passim.

2. Terpander, Stesichorus, and other poets worked in archaic Sparta: Arist. fr. 551 Gigon, Plut. Mor. 1134b,Athen. 14.635e, etc.

3. Nevertheless, Alcman confesses his interest in women in PMGF 34, 59a, b, and see below on Megalostrata, who was not said to have been his pupil.

4. See further Nigel Kennell,“The Elite Women of Sparta,” paper delivered at the annual meeting of the American Philological Association, December 28, 1998; abstract published in American Philological Association 130th Annual Meeting: Abstracts, 84. In this paper, Kennell is less willing to accept the evidence for a girls’ agoge in the Roman period than he was in The Gymnasium of Virtue: Education and Culture in Ancient Sparta (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1995), 46.

5. Though no ancient source states that every girl participated in the system, the universality of the goal implies it. See further Jean Ducat, “Perspectives on Spartan Education in the Classical Period,” in Sparta: New Perspectives, ed. S. Hodkinson and A. Powell (London, 1999), 57–58.

6. See William V. Harris,Ancient Literacy (Cambridge, 1989).

7. See further Paul Cartledge, “Literacy in the Spartan Oligarchy,” JHS 98 (1978), 25–37, esp. 33–37.

8. From the sixth to the fourth century: Cartledge,“Spartan Wives: Liberation or Licence?” CQ 31 (1981), 84–105, esp. 93 n. 54.

9. Thus F. D.Harvey,“Literacy in the Athenian Democracy,” REG 79 (1966), 585–635, esp. 623.

10. At Athens, respectable women who were literate learned their letters at home: Sarah B. Pomeroy, Xenophon. Oeconomicus: A Social and Historical Commentary (Oxford, 1994), 270, 283. For learning in an all-female milieu, cf. the young women in the circles of Sappho and other women poets in archaic Lesbos. The parallel is not exact, however, for several reasons, including the fact that Spartan girls were required to devote a good portion of their time to gymnastics.

11. There is evidence for male leaders of female choirs at Aegina, but the age of the females is not clear: Herod. 5.83.3.

12. Trans. Sarah B. Pomeroy. For further comments on these poems, and a photograph of a portion of one of the papyrus texts, see Appendix.

13. See LSJ s.v. kubernao 2 for associations with chariots and horses, rather than the common interpretation of piloting a ship.

14. PMGF TA 2.34–35,PMGF 1.58, 59, and passim, PMGF 3.8.

15. See chap. 3 nn. 25, 34, and chap. 4.

16. Cf. Agesilaus for another Spartan king who enjoyed the company of his young children, two daughters and a son: Plut. Ages. 25.6, Sayings of Spartans, 213.70.

17. Plut. Sayings of Spartan Women, 241a3, d10, 11. On this source see Appendix. Cf. the letters of Olympias to Alexander: Plut. Alex. 39.4–5.

18. See further Sarah B. Pomeroy, “Technikai kai Mousikai: The Education of Women in the Fourth Century and in the Hellenistic Period,” AJAH2 (1977), 51–68, and Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra (with a new foreword and addenda, Detroit, 1989), 59–72.

19. Diels-Kranz6, vol. 2, p. 408, 2.10, and see Kathleen Freeman, The Pre-Socratic Philosophers (Oxford, 1946), 418–19. For a translation, see Rosamond Kent Sprague, The Older Sophists (Columbia, S.C., 1972),“Dissoi Logoi,” 282.

20. On the ambiguity of paides, which can mean “children,” “boys,” or “slaves,” see below, Appendix n. 77.

21. Advice to the Bride and Groom, 32: see further Sarah B. Pomeroy, ed., Plutarch’s Advice to the Bride and Groom and A Consolation to His Wife (New York, 1999), ad loc.

22. PMGF 59, Poralla2 510.

23. On traditions linking women philosophers to the men in their circle see Pomeroy, “Technikai kai Mousikai,” 58.

24. See further Denys Page, PMG 912; Jeffrey Henderson, Aristophanes: Lysistrata, ed. with introduction and commentary (Oxford, 1987), ad loc.; and Douglas M. MacDowell, Aristophanes: Wasps, ed. with introduction and commentary (Oxford, 1971), ad loc.

25. According to the Scholiast to Lys. 1237 Cleitagora was mentioned in Aristophanes, Danaids (= fr. 271 Kassel-Austin). According to Hesychius, s.v. Kleitagora (k 2913 Latte), she was from Lesbos.

26. Xen. Lac. Pol. 1.3, and below, chap. 6 nn. 3, 19, 21–22.

27. I.e., Cheilonis: Iambl. VP 267, Poralla2 no. 760. For her father, who was ephor in 556, see Poralla2 no. 230. See further Conrad M. Stibbe, Das andere Sparta (Mainz, 1996), 211.

28. See further Holger Thesleff, An Introduction to the Pythagorean Writings of the Hellenistic Period (Åbo, 1961), esp. 77–78, 99, 103–5, 114–16.

29. Manuscripts vary. Nistheadousa is listed with a question mark in Diels-Kranz 58, “Pythagoreische Schule: A. Katalog des Iamblichos,” but not cited in Poralla2 or in LGPN 3A. On these women, see further Gilles Ménage, Historia mulierum philosophorum (1690–92), trans. B. H. Zedler as The History of Women Philosophers (Lanham,Md., 1984), chap. 11.

30. LGPN 3A s.vv. dates Cleaichma to the sixth century, but Autocharidas to the fifth century.

31. Iambl. VP 267.31, see also Porphyry, Pythag. 61, Poralla2 no. 702, and LGPN 3A s.v.

32. Iambl. VP 267, Poralla2 nos. 450, 420. On neo-Pythagorean women, see further Pomeroy, Women in Hellenistic Egypt, 61–65.

33. Plut. Cleom. 2, FGrH III.585, and see further Pomeroy, Families, 65–66.

34. Plut. Cleom. 22.6–7, 38.4. This vivid passage may not only record a real event, but may also reflect the Stoic leanings of Plutarch’s source, Phylarchus: see chap. 4 n. 48, and Appendix.

35. Athen. 14.631c, citing Pindar fr. 112 Snell.

36. S. Constantinidou, “Spartan Cult Dances,” Phoenix 52 (1998), 15–30, esp. 24. For details of manufacture and interpretations, see Appendix, below.

37. Giampiera Arrigoni, “Donne e sport nel mondo greco: Religione e società,” in Le donne in Grecia, ed. Giampiera Arrigoni (Bari, 1985), 55–201, devotes pp. 65–101 (of a total 73 of text [the remainder consists of illustrations and special exegeses]) and nn. 29–185 (of a total 259) to Sparta and uses Sparta as a touchstone throughout the article.

38. B. B. Shefton, “Three Laconian Vase Painters,” ABSA 49 (1954), 299–310, esp. 307, no. 17, for nymphs or girls swimming. Alcman also wrote a work titled “The Female Swimmers” (Kolumbosai: PMGF TB 1, fr. 158).

39. Idyll 18.22–25. Theocritus, of course, is not an unassailable witness to practices in the classical period, but his report is consistent with those from earlier, more trustworthy sources.

40. There is no evidence for the Platanistas (“the grove of plane trees”) before the Hellenistic period, when two teams of youths staged a mock battle.

41. Contra Cartledge, “Spartan Wives: Liberation or Licence?” 91. T. Scanlon, “Virgineum Gymnasium: Spartan Females and Early Greek Athletics,” in The Archaeology of the Olympics, ed. W. Raschke (Madison,Wis., 1988), 185–216, esp. 190, also argues that education was co-ed, but the evidence he cites is tendentious (Eur.Andr. 99–100) and Roman (Ovid,Her. 16. 149–52,Prop. 3.14),when sensationalism may have prompted or intensified participation in co-ed contact sports so that women’s wrestling of the archaic and classical period became the pancration in the Roman period. Philostratus, Imag. 2.6.3, specifies the pancration as the pancration of men (andron). For agele (i.e., agela “herd”) used of girls, see n. 110 below.

42. For a detailed description, see Giovanni Paludetti, Giovanni de Min (Udine, 1959), 290, 307. 310–11, 320,App. 1, and fig. 31.

43. A son of Hippocoön, older brother of Tyndareus, whose other sons are mentioned at the opening of the extant fragment of Alcman, Partheneion 1.

44. Carol Salus, “Degas’ Young Spartans Exercising,” Art Bulletin 67 (1985), 501–6, argues that the subject of the painting is courtship, and that the figure touching the girl’s breast is male (504). However, Degas may be depicting the well-known homosexual relationship between females.

45. Martin Davies, The French School (London, 1957), 70, and see further M. H. Sykes, “Two Degas Historical Paintings: Les jeunes spartiates s’exercent à la lutte and Les malheurs de la ville d’Orléans” (Master’s thesis, Columbia University, New York, 1964).

46. Phoebe Pool, “The History Pictures of Edgar Degas and Their Background,” Apollo 80 (1964), 306–11, esp. 308.

47. Nicolas Richer, Les éphores: Études sur l’histoire et sur l’image de Sparte (viiie–iiie siècle avant Jésus-Christ) (Paris, 1998), esp. 83–84, sees a connection between the Partheniai (“children of unmarried women”) who were sent to settle Tarentum and the Tresantes (“tremblers,”“cowards”), for both are feminized. See further chap. 2 n. 45 below.

48. Xen. Hell. 6.5.27–8; Plut. Ages. 21.4–5;Arist. Pol. 1269b37–9.

49. 273–272 b.c.e.: Plut. Pyrr. 27.2–5, 29.6. Cf. Polyaen. 8.49 and 70 for the military assistance of the women of Cyrene. Jacoby FGrH 81, Komm. F 48, suggests that a similar passage of Pompeius Trogus in Justin is based on Phylarchus. See further David Schaps, “The Women of Greece in

Wartime,” CPh 77 (982), 193–213, and Maria Luisa Napolitano, “Le donne spartane e la guerra: Problemi di tradizione,”AION (archeol.) 9 (Naples, 1987), 127–44.

50. Jerome para. 308 Migne relates several anecdotes about the rape of Spartan virgins in conditions of war. See also Orosius 1.21 and Justin 3.4.1–5.

51. Paus. 4.16.9–10, and see chap. 6 n. 11.

52. Clearchus of Soli (fl. ca. 250 b.c.e.) fr. 73 Wehrli = Athen. 13.555c. New York City firefighters, both male and female, are trained to be able to carry adults of both sexes.

53. See chap. 3 on liquid and dry food rations. Xen. Lac. Pol. 15.3 refers to men eating meat at the syssition (mess group). Spartiates did raise animals on their estates (Plut. Alcib. I 122d).

54. Athen. 10.414d quoting Heraclitus comicus (also known as Heraclides) in “The Host,” Kassel-Austin PCG 5.560.

55. Sayings of Spartans 232d5, Lac. 239a (28).

56. Paus. 3.17.6, 3.15.10; Greek Anthology, Planudian Appendix 173–76, etc., and see further J. G. Frazer, Pausanias’s Description of Greece, vol. 3 (London, 1913), 338.

57. OCD3 s.v. Aphrodite considers the possibility that the armed Aphrodite was connected with women’s education, but prefers to interpret the armor as alluding to Aphrodite considered to be the polar opposite of Ares. Robert Parker,“Spartan Religion,” in Classical Sparta, ed. A. Powell (Norman, Okla. 1989), 142–72, esp. 146, suggests that the portrayals of divinities with armor were retained at Sparta from earlier primitive cult images. See further Fritz Graf, “Women, War, and Warlike Divinities,” ZPE 55 (1984), 245–59, and chap. 6 n. 72 below.

58. On the armed Aphrodite: Julianus (sixth century c.e.,Anth. Pal. 9.447), and Graf,“Women, War, and Warlike Divinities,” 250–51.

59. For Plutarch’s version see above. Arist.Pol. 1337b24–25 lists reading, writing,gymnastics, the musical arts, and possibly painting. In Plato, Laws (804E), riding is prescribed for women.

60. Xenophon, On Horsemanship, Cavalry Commander, and see further, Pomeroy, Xenophon, Oeconomicus, 2, 219, 226, 231, 243.

61. The owner of the horse ridden by Julie Krone, the first woman to win a Triple Crown, said of her: “She’s got great finesse, beautiful hands on a horse, and good communication. You don’t have to bully a horse—just talk to him.” Joe Drape,“Krone Adds Another First to Her Accomplishments,” New York Times,Aug. 8, 2000, sec. D, pp. 1, 5, esp. 5.

62. Dawkins, AO, 146, all dates. Some riders on figurines dated 700–600must have had to ride side-saddle: Dawkins, AO, 150.

63. Dawkins, AO, 157.

64. A. J. B. Wace, M. S. Thompson, J. P. Droop, “The Menelaion,” ABSA 15 (1908), 108–57, esp. 124, all dates, and H. W. Catling,“Excavations at the Menelaion, Sparta,1973–76,”AR(1976–77),24–42, esp. 38, and fig. 42.

65. Mary Voyatzis, “Votive Riders Seated Side-Saddle at Early Greek Sanctuaries,” ABSA 87 (1992), 259–79, esp. 272, 274, for fourteen figures from the Orthia sanctuary, one seventh cent., the others sixth, and five from the Menelaion, all sixth cent.

66. Parthenion 1, 47–59; see also Aristoph. Lys. 1307. Theoc. Id. 18.30 compares Helen to a Thessalian horse, and see chap. 6 n. 47.

67. Scholion B, fr. 6, col. i (P.Oxy. 2389).

68. J.K. Anderson,Ancient Greek Horsemanship (Berkeley, 1961), 36–37.

69. Perhaps mules: Athenaeus’ text is unclear. See further Kaibel (ed.),Athen. 1.317.

70. Athen. 4.139f,Xen. Ages. 8.7, Plut. Ages. 19.5–6.

71. For public models, note that Hellenistic queens were publicly honored by equestrian statues: see E. Fantham et al., Women in the Classical World (New York, 1994), 220, 222. At Rome, Cloelia was portrayed mounted on a horse, though her heroic deed involved swimming: Liv. 2.13.11.

72. Xen. Hell. 3.3.5 for Spartan men out on their country estates.

73. The sole exception is a woman who was dressed up to impersonate Athena and placed in a chariot. She may, however, have had a driver: Herod. 1.60.

74. Liv. 34.1–8;Tac.Ann. 3.34,Val.Max.9.1.3,Oros.4.20.14,Zonaras 9.17.1, and see further SarahB. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity (New York, 1995), 178.

75. According to Arist. HA 608a25, female Laconian hounds are more clever than the males.

76. Poralla2, no. 310.

77. According to Moretti, IAG, pp. 41, 43, Cynisca was born sometime before 427, probably around 440.

78. For a dedication of a small votive by Cynisca to Helen at the Menelaion, see A. M. Woodward,“The Inscriptions,” ABSA 15 (1908), 40–106, esp. 86–87, no. 90 =IG V.1.23.

79. Pausanias (5.6.7; 6.20.9) states that parthenoi (virgins, unmarried women) could view the games, but that married women were excluded. This provision seems extremely unlikely in view of the need to chaperone young girls. Matthew P. J. Dillon,“Did Parthenoi Attend the Olympic Games? Girls and Women Competing, Spectating, and Carrying Out Cult Roles at Greek Religious Festivals,” Hermes 128 (2000), 457–80, esp. 461–62, suggests that fathers accompanied their girls. Pausanias may be thinking about the parthenoi who were present not as spectators, but because they participated in the races at Elis. The only exceptions (not mentioned by Pausanias) were the priestess of Demeter and a female envoy from Ephesus: see L. Robert, “Les femmes théores à Éphèse,” CRAI (1974), 176–81 = OMS 5.669–74. Of course it is possible that even at her advanced age Cynisca was technically a parthenos. Perhaps she had been widowed at a young age. In any case, no husband nor children are recorded for her, and her brother’s attempts to manipulate her (see below) suggest that she did not have a husband. Her single-minded devotion to racing may have not left any time for wifely duties.

80. Paus. 6.1.6: see further Bianchi-Bandinelli, EAA 1.460–61.

81. His name may have been Apelles. Bianchi-Bandinelli, EAA 1.460–61, Pliny HN 34.86. The manuscript variant adornantes (“adorning themselves”) would probably make sense as well in the case of Cynisca, who seems to have been vain and by no means modest. On the commemorative monuments, see J. G. Frazer, Pausanias’s Description of Greece (London, 1913), vols. 3, 4, ad loc.

82. Paus. 6.1.6 = Anth. Pal. 13.16 = IG V.1.1564a = I. Olympia, no.160 = Moretti, IAG, no. 17, and Moretti, I. Olympia, nos. 373, 381.

83. Named for Troilus, famous for his horses, called by Homer hippiocharmes (Il. 24.257:“fight-ing from a chariot”).

84. LGPN 3A s.v., and see n. 77 above.

85. Xen. Ages. 9.6, sim. arete in Plut. Ages. 20.1, and in Sayings of Spartans,Ages. 49.

86. See further Pomeroy, Families, 93–94. Like Cynisca, Bilistiche received divine honors, but this worship was part of the Hellenistic trend to divinize members of the royal families and some of their intimate associates.

87. Moretti, IAG, p. 44, suggests that the sculptures by Apelles were also erected after Cynisca’s death, and commissioned either by her family or by the state.

88. Moretti, I. Olympia, nos. 396, 418.

89. Bilistiche, mistress of Ptolemy II, who was said to be from Argos, Macedonia, or Phoenicia, was the next woman whose victories are recorded: see further Pomeroy, Women in Hellenistic Egypt, 53–55. Her victories were probably in 268 and 264:Moretti, IAG,p. 42. Berenice II was the next woman after Bilistiche whose horses were victorious. Berenice originally came from Cyrene. Her interest in equestrianship is additional testimony to cultural links between Cyrene and Sparta. For the horses of Cyrene see, e.g., Pindar, Pyth. 4.2. According to Strabo (17.3.21 [837]), Callimachus praised the horses of Cyrene. For an epigram attributed to Posidippus comparing Berenice to Cynisca see P. Mil. Vogl. VIII.309, xiii 31–34.

90. Schol. Theoc. 18. 22–5, 39–40: see A. S. F. Gow, Theocritus, vol. 2 (Cambridge, 1952), 354, 358.

91. See below. There was also a race called en Drionas about which little is known: see Hesych. s.v. E2823 (Latte).

92. Hesych. s.vv.Driodones, en Drionas.

93. See further T. Scanlon,“The Footrace of the Heraia at Olympia,”AncW 9 (1984), 77–90.

94. On the connection between Spartan maidens and the races for Hera, see Preface, and Appendix,“Mirrors and Bronze Statuettes.”

95. I.e., 160 meters. David G. Romano, “The Ancient Stadium: Athletics and Arete,” AncW 7 (1983), 9–15, esp. 14, suggests that the length of the girls’ race was correlated with the measurement of the stylobate of Hera’s temple at Olympia, while the length of the boys’ race was correlated with the stylobate of the temple of Zeus. According to Herod. 2.149, the length of the stadion was 6 plethra or 600 feet (168.6 m.). According to Romano’s (p. 14) formula, the girls’ stadion race would be ca. 128 meters.

96. Paus. 5.16.3: see Frazer, Pausanias’s Description of Greece, vol. 3, 593.

97. The girl depicted in fig. 1, above, may be running as part of a dance, for she glances behind her. On the other hand, she may be looking to see if any competitor is catching up.

98. For a survey of nudity in antiquity, see Larissa Bonfante,“Nudity as a Costume in Classical Art,” AJA 93 (1989), 558–68.

99. Ibycus, fr. 339 PMGF; Eur. Andr. 595–601, cf. Hec. 932–36; Soph. fr. 872 Lloyd-Jones, Aelius Dionysius (2d cent. c.e., 4.35 [140] Erbse), for girls wearing one himation only,without belt or chiton; similarly Moeris, a lexicographer (2d cent. c.e., d27).

100. Xen. Lac. Pol. 1.4; Plut. Lyc. 14.4–15.1; Nic. Dam. FGrH 103 F 90, cf. Anacreon fr. 99 (Page-Campbell).

101. Aristoph. Lys. 78–84,Critias fr. 32 (Diels-Kranz 2.1969).